Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to document the growth of postacute care and contemporaneous staffing trends in US nursing homes over the decade 2001 to 2010.

Design

We integrated data from all US nursing homes longitudinally to track annual changes in the levels of postacute care intensity, therapy staffing and direct-care staffing separately for freestanding and hospital-based facilities.

Setting

All Medicare/Medicaid-certified nursing homes from 2001 to 2010 based on the Online Survey Certification and Reporting System database merged with facility-level case mix measures aggregated from resident-level information from the Minimum Data Set and Medicare Part A claims.

Measurements

We created a number of aggregate case mix measures to approximate the intensity of postacute care per facility per year, including the proportion of SNF-covered person days, number of admissions per bed, and average RUG-based case mix index. We also created measures of average hours per resident day for physical and occupational therapists, PT/OT assistants, PT/OT aides, and direct-care nursing staff.

Results

In freestanding nursing homes, all postacute care intensity measures increased considerably each year throughout the study period. In contrast, in hospital-based facilities, all but one of these measures decreased. Similarly, therapy staffing has risen substantially in freestanding homes but declined in hospital-based facilities. Postacute care case mix acuity appeared to correlate reasonably well with therapy staffing levels in both types of facilities.

Conclusion

There has been a marked and steady shift toward postacute care in the nursing home industry in the past decade, primarily in freestanding facilities, accompanied by increased therapy staffing.

Keywords: Long term care, nursing homes, postacute care, nursing home staffing

A variety of changes in how Medicare pays for postacute care have occurred in the past 3 decades. Throughout the 1990s, this resulted in steady growth in the nursing home industry.1 Then, during the late 1990s and early 2000s, the introduction of a prospective payment system (PPS) and other Medicare postacute care payment reforms resulted first in an increased use of Medicare-paid skilled nursing facility (SNF) care and then a decreased use of this care.2,3 Provision of postacute care in nursing homes has not been well documented, especially in recent years. It also remains unclear whether nursing homes have increased staff-to-resident ratios to meet the escalating needs of postacute patients.

Nursing home staffing has been measured numerous ways, including in terms of hours per resident day (HPRD), registered nurse (RN)-to–licensed practical nurse (LPN) or other direct-care staff ratios, and staffing composition (ie the proportion of care provided by different categories of staff). Studies have shown that after Medicare SNF PPS, most nursing homes reduced their RN staffing in terms of both HPRD and RN ratios.4 Increased postacute care for rehabilitation provided in nursing homes would also be expected to boost staffing levels of therapy staff of several types. This includes physical therapists (PTs) and occupational therapists (OTs), who have obtained a graduate degree and are licensed; therapy assistants, who are also licensed and have obtained at least an associate degree; and aides, who are paraprofessionals with no license or degree. However, no studies have yet examined therapy staffing in relation to postacute care provision and little is known about how increases in postacute care affects nursing home staffing, including changes in levels of therapy staffing, changes in staffing composition, or whether there is a relationship between changes in therapy and nurse staffing levels.

Research conducted shortly after the introduction of SNF PPS found that this change in policy resulted in nursing homes being more likely to hire their own therapy staff in-house rather than contracting therapy services from outside vendors, a common practice before PPS.5 However, little is known about the changes that may have taken place in terms of nursing home staffing while this shift to in-house therapy services took place. The purpose of this study was to systematically track the growth of postacute care and contemporaneous staffing trends in nursing homes nationwide over the decade 2001 to 2010.

Methods

We integrated all facilities longitudinally to track annual changes in the levels of staffing and postacute care intensity; in other words, the proportion of care provided in the facility that was Medicare-covered SNF care. We did this separately for freestanding and hospital-based facilities. This cohort of nursing homes was defined using the Online Survey Certification and Reporting (OSCAR) database for 2001 through 2010 and included whichever facilities were in operation and received an inspection survey in any of these years. In other words, facilities that closed during the 10-year period were included for some years and not others; this is also true of new facilities that opened during the study period. Similarly, because inspection surveys can occur every 9 to 15 months, some facilities in operation may not have had an inspection in a given calendar year. The OSCAR data are available from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and are based on information collected from each Medicare/Medicaid-certified nursing home during annual survey inspections. The Residential History File (RHF) was also used to construct several measures. The RHF is a unique data resource built using Medicare enrollment data, Medicare claims data, and nursing home Resident Assessment Instrument Minimum Data Set (MDS) data.6 The RHF can be used to track individuals as they move through the health care system, including between different care settings and different care types (eg SNF care). These data were obtained through a data use agreement (DUA) with CMS.

We used the RHF to construct several measures of nursing home case mix to approximate the intensity of postacute care per facility per year, including the proportion of nursing home person days that were SNF care, the number of admissions per bed, and the average Resource Utilization Group (RUG)7 nursing case mix index for both all admissions to each nursing home and among all residents present on the first Thursday in April each year. To determine the proportion of nursing home days that were SNF, the RHF was used to establish the number of nursing home days for all residents in the facility in the calendar year. The RHF was also used to determine the number of those days that were fee-for-service Medicare-covered SNF days. The proportion of days that were SNF was then calculated using these 2 counts. The annual number of admissions per bed was calculated as the ratio of all (SNF and non-SNF) facility admissions in a given year, derived from the MDS records, divided by the total number of beds in the facility for that year available in the OSCAR. Finally, we calculated the average RUG nursing case mix index (CMI) for both all of the residents admitted to the nursing home in a calendar year and all of those in the facility each year on the first Thursday in April, as determined by the RHF. For each of these groups, the RUG-III 5.12 code was first used to generate a RUG classification for each resident (44 categories in total). Second, the RUG code was converted into a nursing CMI value following the CMS proposed rule regarding fiscal year 2004 SNF payment policies.8

Our staffing measures were based on the HPRD for PTs and OTs, PT and OT assistants and aides, and direct-care staff (RNs, LPNs, and certified nursing assistant [CNAs]) HPRDs. OSCAR data were used to derive these measures for all categories of staff. Nursing home staffing data derived from OSCAR have been used in numerous previous studies.9 As part of the annual certification process, nursing homes report the number of hours during the 2 weeks before their annual survey for a number of staff, including PTs, OTs, RNs, and so forth. CMS converts the number of hours into full-time equivalents (FTEs; based on a 35-hour work week) and this is reported in the annual OSCAR data. For this study, we converted the FTEs into hours per day by multiplying by 5 (again based on a 35-hour work week spread over 7 days) and divided the total number of hours per day by the number of residents in the facility (also drawn from the OSCAR) to arrive at the HPRD. For each facility, we added the number of hours per resident day for PTs and OTs; for example, to get PT and OT HPRDs. We did the same for PT/OT aides and assistants and for direct-care nursing staff, which included the total HPRD for RNs, LPNs and CNAs.

Results

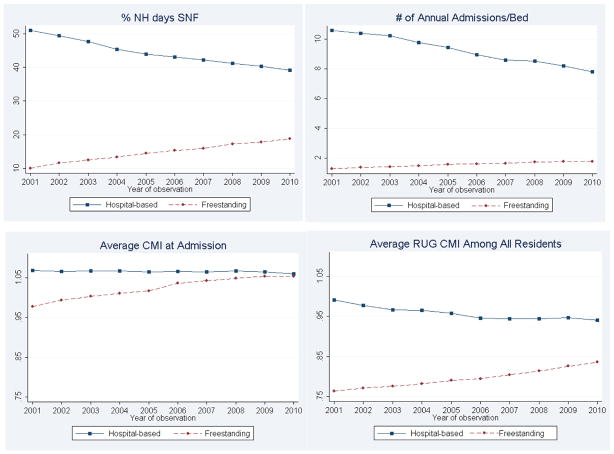

As shown in Figure 1, in freestanding nursing homes (N ranged between a high of 14,626 in 2001 and a low of 14,331 in 2010), all postacute care intensity measures have increased considerably each year throughout the study period. In contrast, in hospital-based facilities (N ranged from a high of 1928 in 2001 and a low of 1051 in 2010) all but one of these measures (average RUG CMI at admission, which has changed little) have decreased precipitously.

Fig. 1.

Trends in postacute care intensity in US nursing homes.

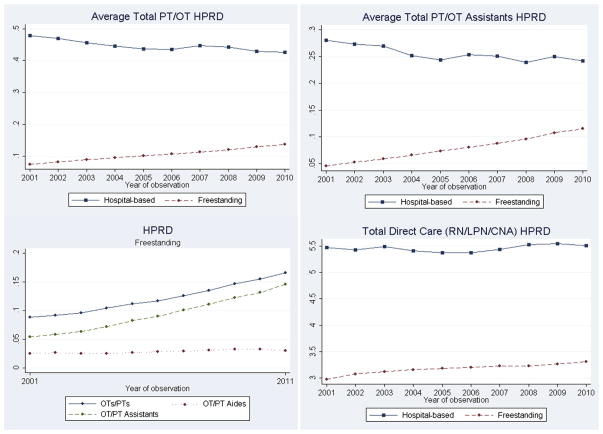

As shown in Figure 2, therapy staffing, including PT and OT HPRD and PT and OT assistants HPRD, has risen in freestanding homes but declined in hospital-based facilities. Nevertheless, postacute care intensity appears to be reasonably correlated with therapy staffing levels in either type of facility. As demonstrated by the graph showing the HPRD for PTs/OTs, assistants and aides in freestanding facilities, PTs/OTs, and PT/OT assistants complement each other rather than substitute for each other, as both have increased steadily throughout the study period. This graph also shows that facilities, on average, are not substituting licensed therapists with aides, as aide HPRDs have remained flat across most of the study period. In addition, as compared with average direct-care HPRD, which has remained relatively flat, therapist HPRDs have risen dramatically, nearly doubling between 2001 and 2010.

Fig. 2.

Trends in staffing in US nursing homes.

Discussion

Our findings illustrate the results of changes to Medicare payment policies, including a dramatic reduction in the number of operating hospital-based facilities between 2001 (1928) and 2010 (1051). This, in turn, has resulted in reduced postacute care intensity in hospital-based facilities, which is primarily because those hospital-based facilities that remained open happened to be owned by hospitals but did not necessarily serve exclusively postacute patients.

Changes to Medicare payment policies have also resulted in hospitals discharging patients to SNFs “sicker and quicker,”10 and this has caused a tremendous increase in postacute care provision in nursing homes, as seen by the increase in the proportion of SNF days and the associated increase in the average RUG CMI. Our results bear this out and demonstrate that nursing homes have also increased therapy-related staffing to meet the rehabilitation needs of these postacute care patients. As more therapy time is devoted to postacute care patients, it should be factored into nursing home performance and quality metrics currently used for public reporting.

Recently, the shift to the 5-star Quality Rating System for reporting nursing home quality has changed the way nursing home staffing is publicly reported. Previously, RN, LPN, and CNA staffing were reported in terms of HPRD. Under the 5-star system, nursing homes now receive a star rating for staffing (1 to 5) based on 2 case mix–adjusted staffing measures: RN HPRD and total nursing HPRD. These 2 measures are weighted equally and nursing homes are assigned a star ranking based on both the intrastate quartile within which they fall and the staffing thresholds established based on the CMS staffing study.11

One major criticism of the 5-star system has been that it does not adequately distinguish between nursing homes providing different types of care by not dividing them into specialized categories or classes.12 For example, nursing homes providing a lot of postacute care may be dedicating more resources toward therapy staffing than nurse staffing. These facilities may receive a lower 5-star rating for staffing, although postacute patients are receiving a good deal of hands-on care from therapists, therapy assistants, and therapy aides. Further, therapy staffing may be more important to the outcomes desired by those receiving postacute care, namely the ability to return to the community and remain there.

Meanwhile, nursing homes should strive to balance staff and resources to ensure that a heightened focus on postacute care does not crowd out or otherwise compromise care provided to most long-stay residents. Our results also demonstrate increased acuity among all nursing home residents, as captured by the RUG CMI for all residents in nursing homes on the first Thursday in April each year. Yet, direct-care staffing HPRDs have remained relatively flat. As average acuity increases among all nursing home residents, facilities should also be increasing direct-care staffing.13

Conclusions

There has been a marked and steady shift toward postacute care in US nursing homes in the past decade, primarily in freestanding facilities. This has been appropriately accompanied by increased therapy staffing. However, measures related to therapy staffing are not currently publicly available, but these could be added to the 5-star rating system. In addition, as nursing homes continue to increasingly serve postacute patients, every effort should be taken to ensure that appropriate staffing resources continue to be dedicated to long-stay residents.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute on Aging (P01AG027296).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kaplan SJ. Growth and payment adequacy of Medicare post-acute care rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:1494–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.08.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin WC, Kane RL, Mehr DR, et al. Changes in the use of postacute care during the initial Medicare payment reforms. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:1338–1356. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00546.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buntin MB, Colla CH, Escarce JJ. Effects of payment changes on trends in post-acute care. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:1188–1210. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00968.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seblega BK, Zhang NJ, Unruh LY, et al. Changes in nursing home staffing levels, 1997 to 2007. Med Care Res Rev. 2010;67:232–246. doi: 10.1177/1077558709342253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zinn JS, Mor V, Intrator OK, et al. The impact of the prospective payment system for skilled nursing facilities on therapy service provision: A transaction cost approach. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:1467–1486. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2003.00188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Intrator OK, Hiris J, Berg K, et al. The residential history file: Studying nursing home residents’ long-term care histories. Health Serv Res. 2011;46:120–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fries BE, Schneider DP, Foley WJ, et al. Refining a case-mix measure for nursing homes: Resource Utilization Groups (RUG-III) Med Care. 1994;32:668–685. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199407000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare program; prospective payment system and consolidated billing for skilled nursing facilities—update; proposed rule. Federal Register. 2003;68:26757–26783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng Z, Katz PR, Intrator OK, et al. Physician and nurse staffing in nursing homes: The role and limitations of the Online Survey Certification and Reporting (OSCAR) system. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2005;6:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosecoff J, Kahn KL, Rogers WH, et al. Prospective payment system and impairment at discharge. The “quicker-and-sicker” story revisited. JAMA. 1990;264:1980–1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kramer AM, Fish R. Appropriateness of Minimum Nurse Staffing Ratios in Nursing Homes: Phase II Final Report. Cambridge, MA: Abt Associates, Inc; 2001. The relationship between nurse staffing levels and the quality of nursing home care. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parenteau MA. Informing consumers through simplified nursing home evaluations. J Leg Med. 2009;30:545–562. doi: 10.1080/01947640903356332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrington C, Kovner C, Mezey M, et al. Experts recommend minimum nurse staffing standards for nursing facilities in the United States. Gerontologist. 2000;40:5–17. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]