Abstract

Background

Longitudinally extensive spinal cord lesions (LESCLs) are believed to occur predominantly with opticospinal multiple sclerosis (OSMS) and are associated with disability.

Objective

To describe the prevalence and patterns of spinal cord lesions in Hispanics with multiple sclerosis (MS) and OSMS and their association with disability.

Methods

Cross-sectional study of 164 patients with complete MRIs. Spinal cord was classified: LESCLs, scattered spinal cord lesions (sSCLs) or no spinal cord lesions (noSCLs). Clinical course was defined as classical MS or OSMS. Risk of disability (Expanded Disability Status Scale ≥4.0) was adjusted for age, disease duration and sex using logistic regression.

Results

125/164(73%) MS patients had spinal cord lesions (sSCLs, 57%; LESCLs, 19%) but only 11(7%) had OSMS. LESCLs were associated with disability (p<0.0001), longer disease duration (p<0.0001) and MS (n=21 vs. n=10 OSMS; p<0.0001). LESCLs was associated with the greatest risk to disability (OR 7.3, 95% CIs1.9-26.5; p=0.003; sSCLs OR 2.5, 95% CIs0.9-7.1; p=0.09) compared with noSCLs.

Conclusion

LESCLs are more common than OSMS and are associated with worse disability even in patients with MS. These results suggest that LESCLs are a more important marker of disability in MS than OSMS and may be an early indicator of more aggressive disease in this population.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, opticospinal, spinal cord, Hispanic, Asian

Introduction

Opticospinal multiple sclerosis (OSMS) is a poor prognostic subgroup of relapsing MS, primarily described in Asians[1]. OSMS is distinguished from classical MS based on clinical relapses to the optic nerve and spinal cord [1–4]. A hallmark of OSMS is the presence of longitudinally extensive spinal cord lesions that extend over at least 3 vertebral segments (LESCLs).But LESCLs are also seen in 14–31%[2,5,6]of Asians with classical MS while the prevalence in whites is only 1–3%[7–9]. This raises the question of whether the presence of LESCLs more so than OSMS could explain why MS seems to be more severe in Asians than whites.

Hispanics are an admix population of European and Asian background[10] with a prevalence of OSMS in Latin America[11] that is thought to be intermediate to that of Asians and whites due to the higher manifestation of optic neuritis and spinal cord syndromes[12,13]. Prognosis in Hispanics living in the United States with MS is unclear primarily because few studies exist [14,15]. Not surprisingly, the prevalence of LESCLs in this population is unknown. In this study we examined the relationship between spinal cord involvement, OSMS and disability in Hispanics with the goal of improving our understanding of prognostic subgroups in relapsing forms of MS.

Methods

Study Population

Data for this cross-sectional study was extracted from the Hispanic MS Registry at the University of Southern California (USC) MS clinics as described in detail elsewhere[14]. Briefly, MRI and basic demographic information were collected from October 2011–2012. Hispanic ethnicity was verified by a comprehensive, self-administered questionnaire. A neurological history, exam and EDSS [16] were performed by an MS specialist. The Institutional Review Board at USC approved this study and all patients gave informed consent prior to participation.

Clinical Characteristics

Clinical MS characteristics were extracted from the medical record system and registry database, as described above. Cases that fulfilled Wingerchuck criteria[17], such as presence of anti-aquaporin 4 or onset brain MRI non-diagnostic for MS, were excluded from the study (4 out of 168). Clinical OSMS was defined as relapses strictly confined to spinal cord and optic nerve involvement with ≥ 5 years disease duration[4]. Cases were characterized with classical MS if they followed a relapsing remitting course with predominant multifocal involvement of the central nervous system, including cerebrum, brainstem and/or cerebellum.

MRI parameters

Magnetic Resonance Imaging’s (MRI) of the brain, cervical and thoracic cord performed with a 1.5 Tesla unit were collected as standard of care at the time of diagnosis with demyelinating disease (Median: 1 year, interquartile range: Q1,0 and Q3,4 years). For brain MRI the following sequences were used: sagittal T1 and FLAIR, axial T1, FLAIR, and T2, axial diffusion, axial ADC and postcontrast T1. For spinal MRI multi-sequence multi-planar imaging was obtained utilizing the following sequences: Saigittal T1, sagittal T2, sagittal T2 STIR, sagittal T1 postcontrast, axial T1 postcotnrast and axial T2. Images were analyzed retrospectively for the present study by a neurologist, and again independently by a neuroradiologist (A.L.) blinded to the studies’ clinical data. Brain MRI was categorized using the Barkhof criteria[18] to recapitulate Asian reports which suggest that Asians with OSMS are less likely to meet this criteria [19,20]. Spinal cord MRI’s were categorized by the extent and location of T2 lesions. Long spinal cord lesions extending > 3 vertebral segments were classified as LESCLs (Figure 1) while any lesion falling short of 3 vertebral segments was termed scattered spinal cord lesions (sSCLs; Figure 2). Of the 206 Hispanic cases available for our review, only 168 cases had complete MRI series. Of those with missing thoracic or cervical MRIs 12 of 22 had cervical and 13 of 18 had thoracic cord lesions.

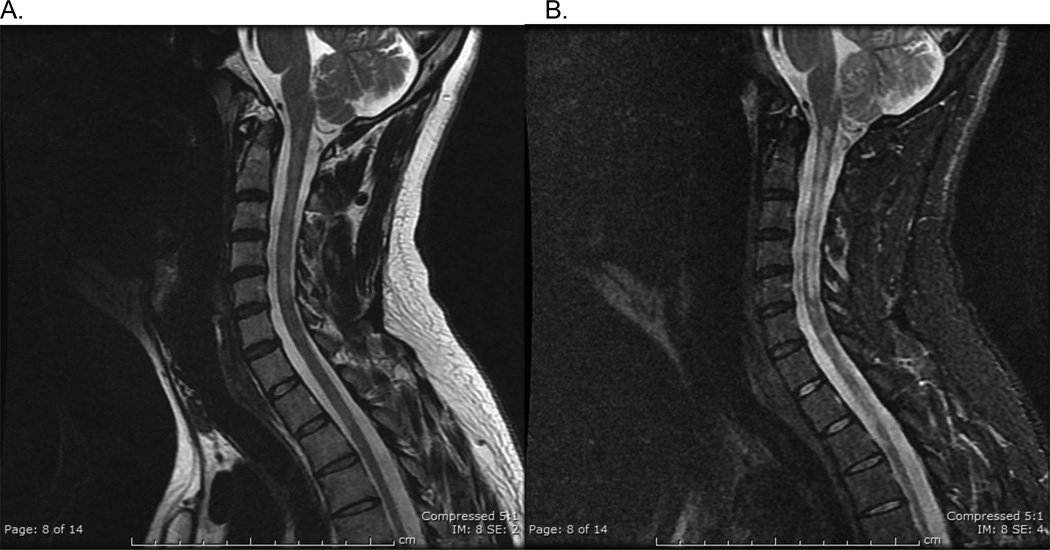

Figure 1.

Hispanic patient with longitudinally extensive spinal cord lesions (LESCLs). A. Sagittal T2frFSE and B. Sagittal STIR images demonstrate a T2 hyperintense spinal cord lesion extending from C1/2 to C5/C6.

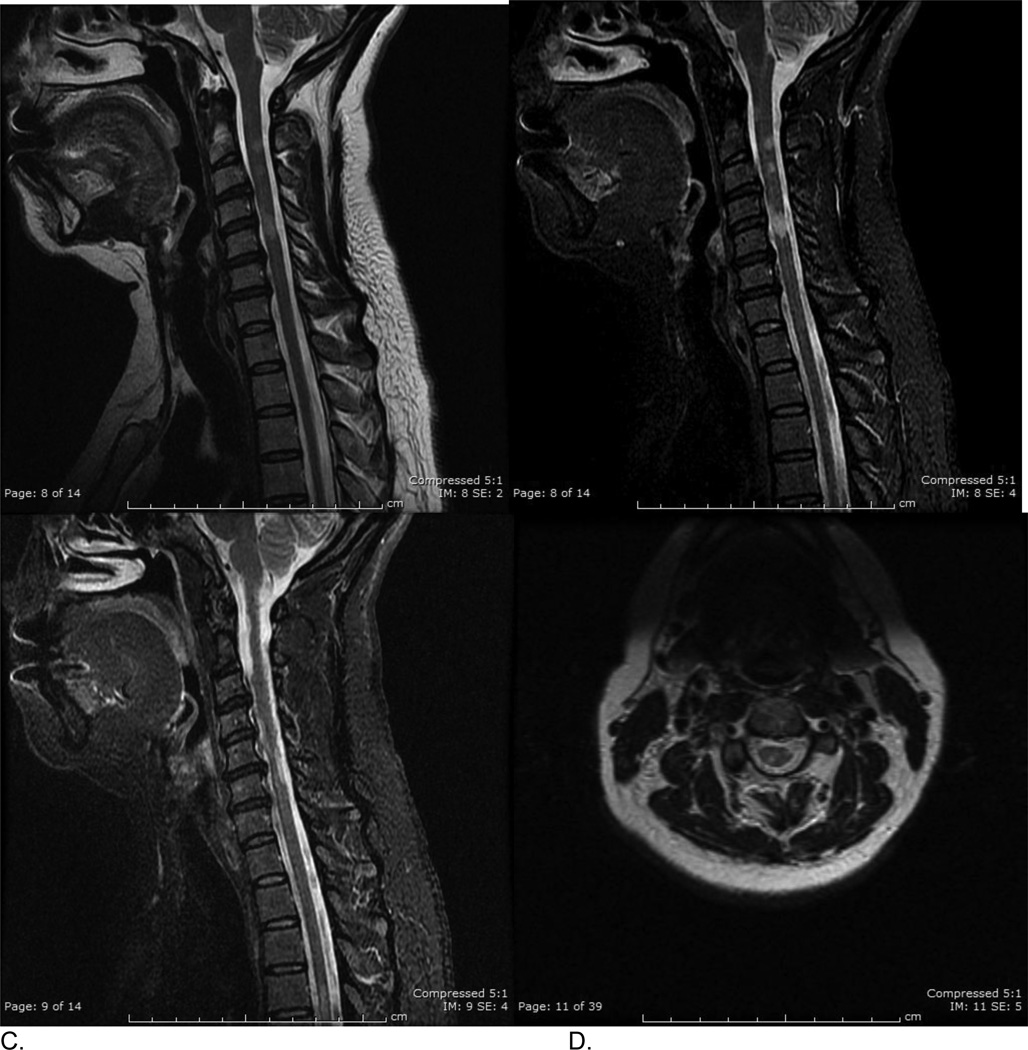

Figure 2.

Hispanic patient with multiple scattered spinal cord lesions (sSCLs). A. Sagittal T2frFSE, B. and C. two sagittal STIR views demonstrate at least 5 scattered T2 hyperintense spinal cord lesions between C1/2 and C6 level. D. axial T2frFSE image at C2/C3 level demonstrates right dorsal column and left lateral column lesions.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted in MS cases with complete MRI series. Inter-rater agreement between neurologist and neuroradiologist was established using Cohen’s Kappa coefficient. We categorized the sample population into three sub groups: presence of LESCLs, sSCLs, and no spinal cord lesions (noSCLs). ANOVA was used to test for statistically significant differences in means of continuous variables between all three subgroups; for variables with non-parametric distributions the Kruskal-Wallis test was preferred. Binary or categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests, respective to the sample size included in the analysis. Logistic regression was used to calculate the odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) associated with EDSS ≥ 4[16] and adjusted for age, gender and disease duration. Additional sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding cases with disease duration less than 5 years. All statistical analyses were performed on SAS 9.2 and set at a priori α-level of 0.05 to declare statistical significance.

Results

Clinical Characteristics

The clinical and demographic characteristics of study participants are presented in Table 1. Participants were predominant women and of Mexican American background (78%). LESCLs were present in 19% (n=31) of patients while only 7% (n=11) met the definition for an OSMS clinical course. All but one OSMS patient had LESCLs. Demyelinating events were similar across groups with the exception of transverse myelitis being a more common syndrome in cases with LESCLs (32%, 28%, 10%, p=0.06), respectively (supplemental Table 1).

Table 1.

MS characteristics by spinal cord involvement

| LESCLs 31 (18.9%) |

sSCLs 94 (57.3%) |

nSCLs 39(23.8%) |

Total N=164 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Frequencies (%) | Frequencies (%) | Frequencies (%) | p-value | ||

| Agea | 40.8 ± 10.94 | 40.1 ± 11.47 | 38.7 ± 9.41 | 39.9 ± 10.87 | 0.70 | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Females | 15 (48.39%) | 55 (58.51%) | 25 (64.10%) | 95 (57.93%) | 0.41 | |

| Male | 16 (51.61%) | 39 (41.49%) | 14 (35.90%) | 69 (42.07%) | ||

| Disease Duration (yr)a | 12.8 ± 8.88 | 7.5 ± 5.69 | 4.9 ± 4.54 | 7.9 ± 6.68 | <0.0001 | |

| ≥5 years, | 25 (81%) | 61 (65%) | 15 (39%) | 101(62%) | ||

| Age symptom onset (yr)a | 25.7 ± 10.88 | 31.4 ± 11.71 | 31.97 ± 8.68 | 30.5 ± 11.08 | 0.03 | |

| Age of diagnosis(yr)a | 28.0 ± 10.62 | 32.6 ± 11.73 | 33.8 ± 9.28 | 32.0 ± 11.10 | 0.07 | |

| Diagnostic Lag Time (yr)a | 2.29 ± 4.68 | 1.18 ± 2.43 | 1.9 ± 3.25 | 1.6 ± 3.17 | 0.19 | |

| EDSS Scoreb | 5.75 (3.0–6.0) | 3.00 (1.0–6.0) | 1.75 (1.0–3.0) | 3.0 (1.0–6.0) | <0.0001 | |

| EDSS ≥ 4 | 21 (67.74%) | 34 (36.11%) | 6 (15.38%) | 61 (41%) | <0.0001 | |

| Clinical OSMS, n (%) | 10 (32.26%) | 1 (1.06%) | 0 | 11 (7%) | <0.0001 | |

| Met Barkhof, n (%) | 28 (90.32%) | 76 (80.85%) | 26 (66.67%) | 130 (79%) | 0.05 | |

Mean ± SD

Median and interquartile range

LESCLs: longitudinal extensive cord lesions; sSCLs: scattered spinal cord lesions; nSCLs: no spinal cord lesions

Clinical characteristics in relation to type of spinal cord lesion

Cases were further classified by the extent of spinal cord involvement: LESCLs, sSCLs and noSCLs (Table 1). Patients with spinal cord involvement had longer disease duration and higher disability levels, particularly among those with LESCLs. Patients with LESCLs were younger at the time of symptom onset but had a longer delay in diagnosis than those with sSCLs and noSCLs. Surprisingly, only 32% of patients with LESCLs were classified as OSMS.

Description of spinal cord and brain

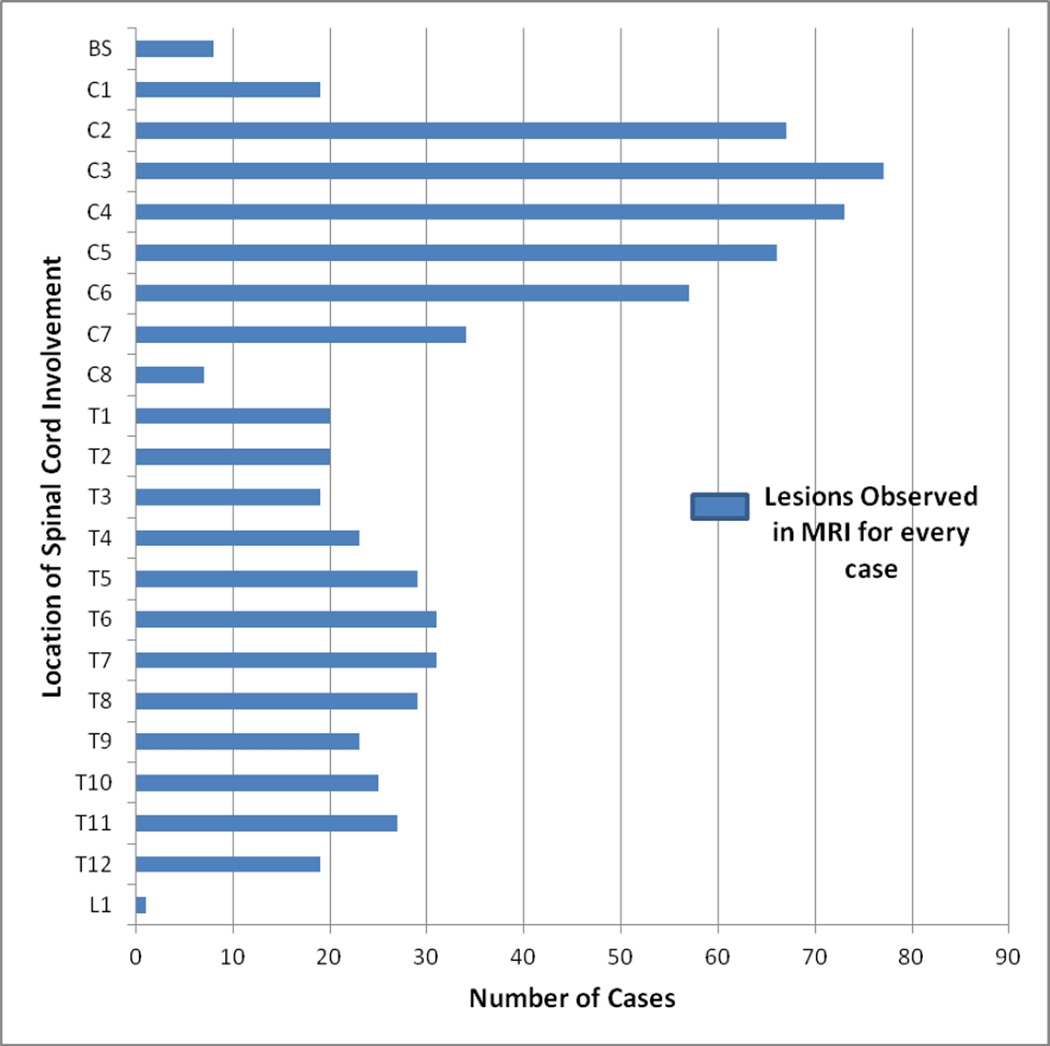

Of the 125 cases with spinal cord lesions, over 95% (n=119) had cervical spine lesions while 60% (n=75) had thoracic spine lesions. Majority of the patients had lesions in C2-C4 regions (Figure 3). Lesions consistent with LESCLs were noted to preferentially involve the cervical spine (81%), as opposed to the thoracic spine (26%) with 6% overlap. Average length of LESCLs was 4.7±1.1 (SD) vertebral segments long. Additionally, we found most patients including those with OSMS had brain lesions (79%, n=130) fulfilling Barkhof criteria[21].

Figure 3.

The frequency of lesions in spinal cord per number of cases. Sections C3 and C4 of the cervical cord was more commonly affected.

Inter-rater agreement was high for both Brain MRIs (k=0.98±0.02, 95% CIs 0.95 to1.02) and spinal cord MRI categorizations (k=0.80±0.20, 95% CIs 0.41to1.19).

Spinal Cord Involvement and Disability

Longer disease duration, older age at the time of data analysis and LESCLs were independently associated with greater disability (Table 2A). After adjusting for age, gender and disease duration, the presence of LESCLs was associated with a 7-fold increased risk of disability (adjusted OR 7.3, 95% CIs 2.0 to 26.5; p=0.003) compared to not having spinal cord lesions. A trend toward greater disability associated with sSCLs was also observed although this did not retain statistical significance after adjusting for other factors (Table 2A).

Table 2.

| A: The association between type of spinal cord lesion and disability (n= 164) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Possible Factors | Disability EDSS (≥4) OR (95% C.I.) |

Disability EDSS (≥4) OR (95% C.I.) |

||

| p-value | p-value | |||

| *Unadjusted | *Adjusted | |||

| Age (yrs) | 1.07 (1.04–1.11) | <0.0001 | 1.07 (1.03–1.11) | 0.0004 |

| Sex (female) | 1.43 (0.75–2.71) | 0.28 | 1.23 (0.57–2.62) | 0.60 |

| Disease duration (yrs) | 1.17 (1.09–1.25) | <0.0001 | 1.12 (1.04–1.21) | 0.004 |

| nSCLs | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | ||

| sSCLs | 3.12 (1.19–8.19) | 0.02 | 2.48 (0.87–7.06) | 0.09 |

| LESCLs | 11.55 (3.66–36.39) | <0.0001 | 7.28 (2.00–26.54) | 0.003 |

| B: Association between possible factors contributing to disability among those with ≥5 years disease duration (n= 101). | ||

|---|---|---|

| Possible Factors | Disability EDSS (≥4) OR (95% C.I.) |

p-value |

| Age (yrs) | 1.06 (1.01–1.12) | 0.02 |

| Sex (female) | 1.31 (0.54–3.18) | 0.55 |

| Disease Duration (yrs) | 1.08 (0.98–1.18) | 0.14 |

| LESCL | 4.21 (0.93–19.17) | 0.06 |

| sSCLs | 1.53 (0.44–5.34) | 0.51 |

| nSCLs | 0 (ref) | |

Logistic Regression

LESCLs: longitudinal extensive cord lesions; sSCLs: scattered spinal cord lesions; nSCLs: no spinal cord lesions

Additional analysis restricted to those with longer disease duration (≥5 years) was performed to mirror the disease duration required to satisfy the OSMS subtype definition. In this restricted model, the presence of LESCLs was still associated with greater disability compared to no spinal cord lesions (OR 4.2, 95%Cis 0.93 to 19.2; p=0.06).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study we found that spinal cord lesions in Hispanics with MS are common, including the presence of LESCLs. We found significant associations between LESCLs and greater disability despite the surprising low prevalence of clinical OSMS in patients with LESCLs. These findings imply that the presence of LESCLs may be a better way to identify poor prognostic relapsing MS subgroups than the OSMS phenotype.

The prevalence of LESCLs in our Hispanic cohort (19%) is surprisingly similar to the 14%[5], 26%[14], and 32%[2]reported in Asians cohorts. This is in contrast to the much lower prevalence estimates of LESCLs in whites with MS (2–3%)[7,22,9]. It is tempting to speculate that this may be due to a high level of Asian ancestry or admixture in our cohort [23]. However, other differences like referral center bias that varies by race/ethnicity [22], differences in disease duration to time of MRI, and earlier studies with lower quality MRI scans[7] could also explain why we found a much higher prevalence of LESCLs than has previously been reported in whites.

Our finding that increasing involvement of the spinal cord on MRI is associated with greater disability is consistent with previous studies in whites which showed that spinal cord symptoms at onset in patients is a robust predictor of long term disability in patients with relapsing-onset MS[24]. Similarly, our finding that LESCLs in particular are strongly associated with greater disability is consistent with previous studies in Asians with MS irrespective of their clinical course [2].

In our cohort, only 7% followed an OSMS course according to our a priori definition despite a relatively high proportion of patients with LESCLs. The prevalence of OSMS was less than we expected based on previous reports in Asians of 15–40%[1]. We think this lower than expected prevalence of OSMS is most likely due to our stringent OSMS criteria in addition to excluding cases that would suggest neuromyelitis optica at onset of disease (such as presence of aquaporin-4 antibody and/or brain MRI non-diagnostic for MS). No consensus definitions for OSMS exist. Our a priori defined criteria included blinding to the presence of LESCLs at the time of clinical classification and required absence of relapses outside of the optic nerve and spinal cord for the first five years. Most studies have used imprecise definitions of OSMS and accepted other relapses despite defining relapses “predominantly” confined to the optic nerve and spinal cord [2,20,25]. The inconsistent blinding to MRI findings is an additional factor. This increases the likelihood that an assessor may be more lenient in assigning an OSMS course to a patient with LESCLs even if relapses outside of the optic nerve and spinal cord occurred and lead to a higher prevalence of OSMS than in our study.

This study is limited by the cross-sectional design and the relative small sample of OSMS and those without any spinal cord involvement. While this study provides important information on the overall relationship of spinal cord lesions and disability in Hispanics, it cannot address if LESCLs predict future disability or simply occur simultaneously with disability. Strengths of this study include use of a priori defined OSMS case definition blinded to MRI findings; MRI assessments by 2 readers with high inter-rater agreement blinded to clinical status; and the relatively large number of subjects with complete clinical and MRI data.

In this study, LESCLs were more common in patients with classical MS than OSMS and are associated with worse disability. These results suggest that LESCLs may be a more sensitive marker of disability in MS than OSMS subtype and may be an early indicator of more aggressive disease. Future studies are needed to clarify whether LESCLs predict future disability and if subtyping by degree of spinal cord could have clinical implications in the treatment of MS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Christen Weber, Abraham Aguilar, and Maura Fernandez for their contributions to data collection/recruitment and the subjects from the Hispanics with MS registry for their participation in the study.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH), through Grant Award Number KL2TR000131 and Nancy Davis Foundation young investigator award to L. Amezcua.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: Amezcua, Lerner and Langer-Gould. Acquisition of data: Amezcua, Lerner, and Ladezma. Analysis and interpretation of data: Amezcua, Ladezma, and Langer-Gould. Drafting of the manuscript: Amezcua and Langer- Gould. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Amezcua, Conti, Langer-Gould, Weiner, Law. Statistical analysis: Amezcua, Ladezma and Conti. Obtained funding: Amezcua. Administrative, technical, and material support: Amezcua and Ladezma. Study supervision: Conti and Langer-Gould.

Financial Disclosure: Dr Amezcua has received honoraria for advisory boards and grant support from Acorda, Biogen and Novartis. Dr. Weiner has received consulting honoraria from Teva and Genzyme. Dr. Law has a research grant from Bayer Healthcare, receives honoraria from Toshiba Medical, iCAD Inc, Fuji Film, Bracco Diagnostics. All others have nothing to report.

References

- 1.Kira J. Neuromyelitis optica and opticospinal multiple sclerosis: Mechanisms and pathogenesis. Pathophysiology : the official journal of the International Society for Pathophysiology / ISP. 2011;18(1):69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsuoka T, Matsushita T, Osoegawa M, Ochi H, Kawano Y, Mihara F, Ohyagi Y, Kira J. Heterogeneity and continuum of multiple sclerosis in Japanese according to magnetic resonance. imaging findings. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2008;266(1–2):115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cree BA, Khan O, Bourdette D, Goodin DS, Cohen JA, Marrie RA, Glidden D, Weinstock-Guttman B, Reich D, Patterson N, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance M, DeLoa C, Oksenberg JR, Hauser SL. Clinical characteristics of African Americans vs Caucasian Americans with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;63(11):2039–2045. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000145762.60562.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cree BA, Reich DE, Khan O, De Jager PL, Nakashima I, Takahashi T, Bar-Or A, Tong C, Hauser SL, Oksenberg JR. Modification of Multiple Sclerosis Phenotypes by African Ancestry at HLA. Archives of neurology. 2009;66(2):226–233. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su JJ, Osoegawa M, Matsuoka T, Minohara M, Tanaka M, Ishizu T, Mihara F, Taniwaki T, Kira J. Upregulation of vascular growth factors in multiple sclerosis: correlation with MRI findings. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2006;243(1–2):21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minohara M, Matsuoka T, Li W, Osoegawa M, Ishizu T, Ohyagi Y, Kira J. Upregulation of myeloperoxidase in patients with opticospinal multiple sclerosis: positive correlation with disease severity. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2006;178(1–2):156–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tartaglino LM, Friedman DP, Flanders AE, Lublin FD, Knobler RL, Liem M. Multiple sclerosis in the spinal cord: MR appearance and correlation with clinical parameters. Radiology. 1995;195(3):725–732. doi: 10.1148/radiology.195.3.7754002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu JS, Zhang MN, Carroll WM, Kermode AG. Characterisation of the spectrum of demyelinating disease in Western Australia. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2008;79(9):1022–1026. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.131177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiu W, Wu JS, Zhang MN, Matsushita T, Kira JI, Carroll WM, Mastaglia FL, Kermode AG. Longitudinally extensive myelopathy in Caucasians: a West Australian study of 26 cases from the Perth Demyelinating Diseases Database. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2010;81(2):209–212. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.172973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rivera VM. Multiple sclerosis in Latin America: reality and challenge. Neuroepidemiology. 2009;32(4):294–295. doi: 10.1159/000204913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luetic G. MS in Latin America. International MS journal / MS Forum. 2008;15(1):6–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanchez JL, Palacio LG, Uribe CS, Londono AC, Villa A, Jimenez M, Anaya JM, Jimenez I, Camargo M, Arcos-Burgos M. Clinical features of multiple sclerosis in a genetically homogeneous tropical population. Multiple sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2001;7(4):227–229. doi: 10.1177/135245850100700403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corona T, Roman GC. Multiple sclerosis in Latin America. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;26(1):1–3. doi: 10.1159/000089230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amezcua L, Lund BT, Weiner LP, Islam T. Multiple sclerosis in Hispanics: a study of clinical disease expression. Multiple sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2011;17(8):1010–1016. doi: 10.1177/1352458511403025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buchanan RJ, Zuniga MA, Carrillo-Zuniga G, Chakravorty BJ, Tyry T, Moreau RL, Huang C, Vollmer T. Comparisons of Latinos, African Americans, and Caucasians with multiple sclerosis. Ethnicity & disease. 2010;20(4):451–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS) Neurology. 1983;33(11):1444–1452. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.11.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, Weinshenker BG. Revised diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology. 2006;66(10):1485–1489. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000216139.44259.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barkhof F, Filippi M, Miller DH, Scheltens P, Campi A, Polman CH, Comi G, Ader HJ, Losseff N, Valk J. Comparison of MRI criteria at first presentation to predict conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis. Brain. 1997;120(Pt 11):2059–2069. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.11.2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chong HT, Kira J, Tsai CP, Ong B, Li PC, Kermode A, Tan CT. Proposed modifications to the McDonald criteria for use in Asia. Mult Scler. 2009;15(7):887–888. doi: 10.1177/1352458509104587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamura M, Houzen H, Niino M, Tanaka K, Sasaki H. Relationship between Barkhof criteria and the clinical features of multiple sclerosis in northern Japan. Multiple sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2009;15(12):1450–1458. doi: 10.1177/1352458509350305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barkhof F, Filippi M, Miller DH, Tofts P, Kappos L, Thompson AJ. Strategies for optimizing MRI techniques aimed at monitoring disease activity in multiple sclerosis treatment trials. Journal of neurology. 1997;244(2):76–84. doi: 10.1007/s004150050053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufman MD, Johnson SK, Moyer D, Bivens J, Norton HJ. Multiple sclerosis: severity and progression rate in African Americans compared with whites. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation / Association of Academic Physiatrists. 2003;82(8):582–590. doi: 10.1097/01.PHM.0000078199.99484.E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shtir CJ, Marjoram P, Azen S, Conti DV, Le Marchand L, Haiman CA, Varma R. Variation in genetic admixture and population structure among Latinos: the Los Angeles Latino eye study (LALES) BMC genetics. 2009;10:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-10-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langer-Gould A, Popat RA, Huang SM, Cobb K, Fontoura P, Gould MK, Nelson LM. Clinical and demographic predictors of long-term disability in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Archives of neurology. 2006;63(12):1686–1691. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.12.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakashima I, Fukazawa T, Ota K, Nohara C, Warabi Y, Ohashi T, Miyazawa I, Fujihara K, Itoyama Y. Two subtypes of optic-spinal form of multiple sclerosis in Japan: clinical and laboratory features. Journal of neurology. 2007;254(4):488–492. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0400-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.