Abstract

Introduction. Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis occurs in about 5% of cancer patients. Ocular involvement is a common clinical manifestation and often the presenting clinical feature. Materials and Methods. We report the case of a 52-year old lady with optic neuritis as isolated manifestation of neoplastic meningitis and a review of ocular involvement in neoplastic meningitis. Ocular symptoms were the presenting clinical feature in 34 patients (83%) out of 41 included in our review, the unique manifestation of meningeal carcinomatosis in 3 patients (7%). Visual loss was the presenting clinical manifestation in 17 patients (50%) and was the most common ocular symptom (70%). Other ocular signs were diplopia, ptosis, papilledema, anisocoria, exophthalmos, orbital pain, scotomas, hemianopsia, and nystagmus. Associated clinical symptoms were headache, altered consciousness, meningism, limb weakness, ataxia, dizziness, seizures, and other cranial nerves involvement. All patients except five underwent CSF examination which was normal in 1 patient, pleocytosis was found in 11 patients, increased protein levels were observed in 16 patients, and decreased glucose levels were found in 8 patients. Cytology was positive in 29 patients (76%). Conclusion. Meningeal carcinomatosis should be considered in patients with ocular symptoms even in the absence of other suggestive clinical symptoms.

1. Introduction

Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis results from dissemination of malignant cells to leptomeninges and can be observed in about 5% of patients with malignancies, but it is likely to become more frequent with the increase of life expectancy in cancer patients [1]. Neoplastic cells may spread to the subarachnoid space through (1) arterial circulation or, less frequently, through (2) retrograde flow in venous systems or (3) as a direct consequence of preexisting brain metastases or (4) through migration of neoplastic cells from the original tumor along perineural or perivascular spaces [2, 3]. Clinical manifestations can be highly variable and may affect both central (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS). CNS involvement may lead to generalised symptoms such as seizures, confusion, encephalopathy, or intracranial hypertension as well as, less frequently, to focal neurological symptoms, mainly consisting in hemiparesis or aphasia. PNS involvement may present with lumbar and cervical radiculopathies or cranial neuropathies [2]. Ocular symptoms even in the absence of other clinical symptoms may represent the initial manifestation of meningeal carcinomatosis. Thus, meningeal carcinomatosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis in selected patients even if making the diagnosis is often challenging. Diagnostic tools consist mainly of contrast enhanced CT and MRI and lumbar puncture. Treatment options such as radiation and intrathecal chemotherapy are often palliative with an expected median patient survival of 2 to 6 months [2].

2. Case Report

A 52-year old lady was referred to our hospital for acute onset, ten days before hospitalization, of left orbital pain and visual loss associated with mild frontal throbbing headache. As symptoms progressed, she underwent ophthalmological evaluation as outpatient six days after symptoms onset, without evidence of significant visual loss and normal fundus oculi examination. Ocular computed tomography performed at that time was unremarkable. On subsequent ophthalmological evaluation five days later a significant visual loss in the left eye was evident with substantially normal fundus oculi examination. She underwent right mastectomy and hormonal therapy (tamoxifen) for infiltrative breast carcinoma in 2007 followed by chemotherapy with AC (cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin) for six months, followed by letrozole. She was on regular followup.

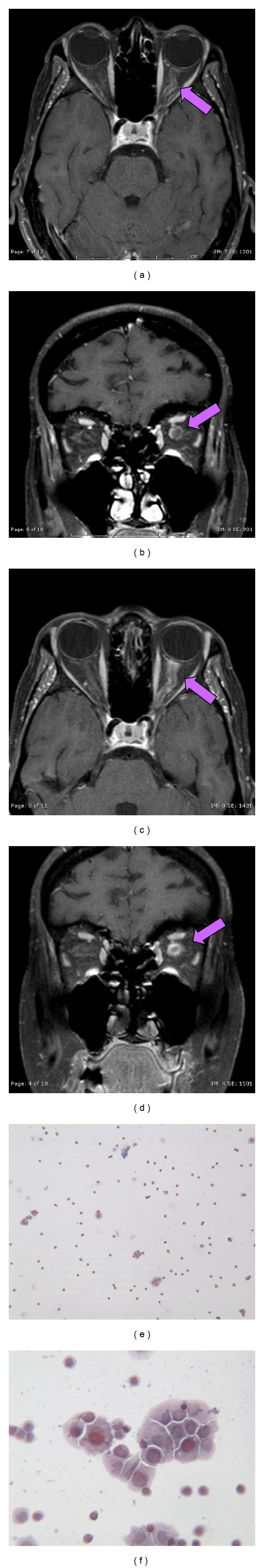

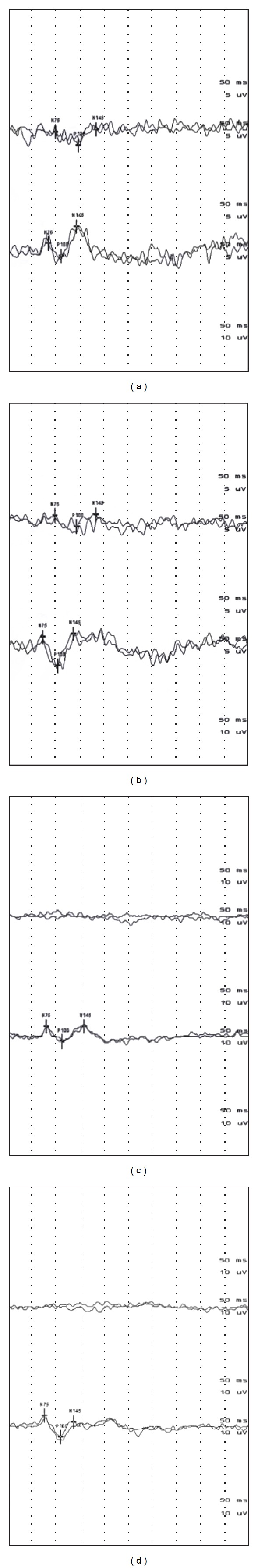

On admission in August 2011 neurological examination was normal except for mild anisocoria (left > right) with detectable Markus Gunn sign, left eye visual loss, and global reduction of deep tendon reflexes. She underwent contrast-enhanced cerebral MRI showing nonspecific signal alteration involving frontal subcortical and periventricular white matter and focal contrast enhancement involving the left optic nerve sheath (see Figure 1). VEP revealed destructured response, reduced amplitude, and prolonged latency on the left (see Figure 2). Lumbar puncture revealed increased cell count (50 cells/mmc) with normal glucose and proteins. Oligoclonal bands were found on CSF but not in serum suggesting intrathecal immune response. Cytology at that time was negative for neoplastic cells and repeated ophthalmological evaluations revealed further progression to complete visual loss in the left eye. Serum antibodies (LAC, ACA, Anti-beta2-glycoprotein ANA, anti-ds-DNA, ENA, c-ANCA, and p-ANCA) were negative. A diagnosis of possible inflammatory optic neuropathy was done. She was started on EV steroids followed by oral tapering without improvement.

Figure 1.

((a)–(d)) Contrast-enhanced cerebral MRI showing diffuse enhancement of the left optic nerve at onset ((a), axial T1; (b), coronal T1) and at 2 months followup ((c), axial T1_SE_FSAT; (d) coronal T1_SE_FSAT). ((e)-(f)) Cerebrospinal fluid cytology showing atypical epithelial cells aggregates.

Figure 2.

Visual evoked potentials (VEPs) at onset ((a), (b)) and at two months follow-up ((c), (d)). (a)-(b): Response at 15 (a) and 30 (b) sec showing destructured response, reduced amplitude and prolonged latency on the left and normal response on the right side. (c)-(d): Response at 15 (c) and 30 (d) sec revealing absent response on the left and destructured response with normal amplitude and latency on the right side.

In about two months she started to complain of left hearing loss. Brainstem auditory-evoked potentials were normal on the left (see Figure 2) and audiological evaluation evidenced mild neurosensorial failure more evident on the right. She underwent contrast-enhanced cerebral MRI in October 2011 showing increased enhancement of the left optic nerve sheath. Repeated ophthalmological evaluation revealed bilateral (left > right) papilledema and she was hospitalized. Neurological examination on admission showed total blindness in the left eye with absent pupillary response to direct light stimulation. VEP revealed absent response on the left and destructured response with normal amplitude and latency on the right (see Figure 2). Cerebral and spine MRI were unchanged except for nonspecific cerebellar enhancement. She underwent repeated lumbar puncture showing further increase of white cell count (105 cells/mmc) and reduced glucose. Citology was positive for atypical epithelial cells (see Figure 1). That was diagnostic for meningeal carcinomatosis. She was referred to the Oncology Department for further evaluation and treatment.

3. Search Strategies and Methods

References for this review were identified through a search of PubMed from 1966 to March 8, 2012 with the terms “meningeal carcinomatosis,” “meningeal carcinomatosis and review,” “meningeal carcinomatosis and optic neuritis,” “meningeal carcinomatosis and ocular manifestations,” and “neoplastic meningitis.” Reference lists of relevant articles were also reviewed. Only articles with ocular manifestation as presenting or associated clinical features were included in our review.

4. Results

We found a total of 34 papers including 33 case reports (34 patients) and 1 case series (7 patients). Information about demographic details along with clinical, instrumental, and radiological findings were recorded and summarized in Table 1. In details we looked at latency between symptoms onset and diagnosis of meningeal carcinomatosis: the mean time was 4 months, while the mean time between primary tumor diagnosis and carcinomatosis diagnosis was 20 months. Six patients (14%) had a postmortem diagnosis.

Table 1.

Clinical and instrumental findings in patients with meningeal carcinomatosis (review of literature).

| Study reference | Age and gender | Latency symptoms onset diagnosis | Ocular manifestations | Associated clinical features | Imaging | CSF examination | Original tumor | Treatment | Life expectancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [4] | 75, M | Not specified | Diplopia, left ptosis, anisocoria | Headache, confusion, hearing loss, VII cn (cranial nerve) palsy | CT scan (normal), MRI (GME) | (1) Prot ↑ (2) not performed |

Bladder and prostate cancer | Declined | 15 days |

|

| |||||||||

| [5] | 49, F | 10 months | Blurred vision and diplopia, horizontal nystagmus | Dizziness, ataxia, seizures, dysarthria, VII cn palsy, left lower limb weakness | CT scan (normal), MRI + gad (FME, cauda equine, cerebellum) | (1) MTC positive (2) not performed |

Ovarian cancer | WBRT. IT: topotecan (0.4 mg × 4) |

4 months |

|

| |||||||||

| [6] | 39, F | 6 months | Sudden bilateral visual loss, horizontal gaze palsy | headache, vertigo, seizures | MRI + gad (GME) | (1) Prot ↑, glu ↓, MTC + (2) MTC negative |

Gastric adenocarcinoma | RT. IT: MTX (12.5 mg × 2/we) |

— |

|

| |||||||||

| [7] | 40, F | 2 months | Visual loss, bilateral sixth cn palsy, bilat papilledema | Headache, neck pain, meningism | Contrast CT scan (GMEt); MRI + gad (GME) | (1) Prot ↑, glu ↓ (2) negative |

Melanoma | Not done | 1 year (after symptoms onset) |

|

| |||||||||

| [8] | 33, F | 11 months | VI cn palsy | Confusion, seizures, increased intracranial pressure | CT scan (FME, lateral ventricles) | Not performed | Uterine cervical neuroendocrine tumor | RT | 19 months (after cancer diagnosis) |

|

| |||||||||

| [9] | 58, M | 2 months (symptoms), 12 months (carcinomatosis) |

Left homonymous hemianopia | Headache, ataxia | CT scan and MRI (right infarction of the caudate, internal capsule, and lentiform nucleus) | (1) MTC positive (2) not performed |

Transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder | Not done | — |

|

| |||||||||

| [10] | 54, F | Postmortem diagnosis of the original tumor, 4 months (symptoms-carcinomatosis) | Ptosis, right III cn palsy | V and XII cn palsy, dysgeusia | MRI + gad (GME) | Not performed | Collecting duct carcinoma | IV: mannitol, dexamethasone, and morphinehydrochloride | 3 months |

|

| |||||||||

| [11] | 65, M | 2 years (carcinomatosis), 6 weeks (symptoms) | Right visual loss | Hearing loss, ataxia | MRI + gad (normal), repeated MRI + gad (FME. bilateral optic nerves, left V cn), bilateral cerebellopontine angle mass | (1) Prot ↑, glu ↓, MCT negative (2) not performed |

Colorectal cancer | RT | — |

|

| |||||||||

| [12] | 61, M | Postmortem diagnosis | III cranial nerve palsy | Flaccid paraparesis with bladder retention, dysarthria, VII cn palsy, right arm weakness | MRI + gad (normal) | (1) Normal (2) Prot ↑, glu ↓, cells ↑ |

Lung adenocarcinoma | Not done | — |

|

| |||||||||

| [13] | 51, F | 15 years (carcinomatosis), 2 months (symptoms) |

Diplopia (VI cn palsy) | Paraparesis with bladder retention, peripheral neuropathy | MRI (normal) | (1) Prot ↑, MTC positive (2) MTC negative |

Breast Cancer |

IT: MTX (15 mg), liposomal Ara-C | Last followup: 3 years and 7 months after carcinomatosis diagnosis (clinically stable) |

|

| |||||||||

| [14] | 67, M | 2 months (symptoms) | Left ptosis, diplopia, and visual loss | Headache, hemifacial sensory loss, paraplegia | MRI (GME, left retrorbital mass) | (1) Cells ↑, MTC negative (2) MTC positive |

Adrenal extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma | IV: dexamethasone | 2 months (after symptoms onset) |

|

| |||||||||

| [15] | 53, M | 4 months (carcinomatosis) | Intermittent diplopia | Headache, vertigo | CT scan and MRI + gad (normal) | (1) Normal (2) MTC positive |

Gastric cancer | RT(45 Gy), betamethasone (16 mg/die) | 3 months |

|

| |||||||||

| [16] | 43, F | 156 months (carcinomatosis) | Progressive blurred vision and pain in the right eye | — | MRI + gad (FME, right optic nerve ) | (1) MCT positive (2) not performed |

Cervical cancer | RT + triethylenethiophosphoramide | 2 months |

|

| |||||||||

| [17] | 56, M | 4 days (symptoms) | III cranial nerve palsy | Headache, nausea, and low back pain | MRI + gad (normal) | (1) MTC positive (2) not performed |

Lung cancer | — | — |

|

| |||||||||

| [18] | 31 (average); 3M, 4F |

Average: 8 months (carcinomatosis) | Ptosis (2), diplopia (3), visual loss (3) |

Headache (4), VII cn palsy (1) |

MRI + gad (2 FME, cn, 2 GME, 3 normal) | (1) MTC positive (2) normal |

NHL (3), ALL (1), AML (1), plasmablastic myeloma (1), breast cancer (1) | Ns | Average: 55 days |

|

| |||||||||

| [19] | 50, F | 2 years (carcinomatosis) | Bilateral loss of vision | Confusion, headache | MRI + gad (thickening intraorbital optic nerves) | (1) Prot ↑, MCT positive (2) not performed |

Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma | Ns | Ns |

|

| |||||||||

| [20] | 44, M | 3 months (symptoms carcinomatosis) | Diplopia | Headache, confusion, meningeal signs, facial diplegia, ataxia, deafness | MRI (normal) | (1) Cells ↑, prot ↑, MTC positive (2) MTC negative |

Lung cancer | IT: MTX (10 mg), Ara-C (39 mg). RT | 182 days (after carcinomatosis diagnosis), 272 days (after symptoms onset) |

|

| |||||||||

| [21] | 67, F | 6 months (carcinomatosis) | Blurred vision, diplopia | Headaches, meningeal signs, and SIADH | CT scan (normal) | (1) MTC positive (2) not performed |

Gastric cancer | RT | 7 months (after cancer diagnosis), 2 weeks (after carcinomatosis diagnosis) |

|

| |||||||||

| [22] | 41, M | 2 weeks (symptoms) | Visual loss, left ptosis | Headache, nausea | Contrast CT scan (chiasmal thickening), MRI (hydrocephalus, increased CSF signal in the basal cisterns) | (1) Prot ↑, MTC negative (2) prot ↑, MTC negative |

Rectal carcinoma | Oral: dexamethasone (4 mg) | 5 days (after carcinomatosis diagnosis) |

|

| |||||||||

| [23] | 60, F | 2 weeks (symptoms) | Diplopia, VI cn palsy | Ataxia, VII cn palsy, and hearing loss | CT scan (normal) | (1) Glu ↓, prot ↑, cells ↑, MTC positive (2) MTC negative |

Gallbladder carcinoma | IT: MTX | 2 months and 2 weeks (after symptoms onset) |

|

| |||||||||

| [24] | — | 5 months (carcinomatosis) | Bilat visual loss papilledema, exotropia, ocular pain | Hemiplegia, SAH | CT scan (normal), MRI (normal) | (1) MTC positive (2) not performed |

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | IT: MTX, corticosteroids | 2 weeks (after carcinomatosis diagnosis) |

|

| |||||||||

| [25] | 49, M | Postmortem diagnosis (2 months after symptoms onset) | Visual loss, bilateral blindness | Headache, confusion, leg weakness, dysphagia, seizures, ataxia, and intermittent paralysis | CT scan (normal) | (1) Normal (2) not performed |

Oesophageal adenocarcinoma | Not done | 60 days (after symptoms onset) |

|

| |||||||||

| [26] | 44, M | — | Diplopia | Headache, ataxia, meningeal signs, V, VII, IX, and X cn palsy | — | (1) Cells ↑, MTC positive (2) not performed |

— | IT: Ara-C.RT | — |

|

| |||||||||

| [27] | 35, F | 20 weeks (carcinomatosis), 1 week (symptoms) | Bilat visual loss to blindness | Headache, vomiting, meningeal signs, and loss of consciousness | CT scan (normal) | (1) Prot ↑, glu ↓, cells ↑, MTC positive (2) prot ↑, MTC positive |

Breast cancer | IT: MTX (70 mg tot), Ara-C (80 mg tot) | 21 days (after symptoms onset) |

|

| |||||||||

| [28] | 36, F | NS | Blindness | Headache, loss of consciousness | CT scan (normal) | (1) MTC negative (2) MTC positive |

Lung cancer | IT: MTX, Ara-C, ACNU, IL-2 | 2 years (after carcinomatosis diagnosis) |

|

| |||||||||

| [29] | 60, F | 3 months (symptoms carcinomatosis) | Visual loss | Headaches, paraparesis | CT scan (normal), repeated CT scan of brain and orbits (right globe soft mass) | (1) Prot ↑, cells ↑ (2) prot ↑, cells ↑, MTC positive |

Gastric cancer | Prednisone (80 mg) | — |

|

| |||||||||

| [30] | 37, F | — | Diplopia | Headache, nausea, vomiting, and meningeal signs | — | (1) MTC positive (2) MTC negative |

Gastric cancer | IT: MTX, Ara-C, prednisolone IV: adriamycin, ftorafur |

365 days (after symptoms onset) |

|

| |||||||||

| [31] | 58, M | Postmortem diagnosis | Visual loss | Vertigo, loss of consciousness | — | (1) Cells ↑ (2) not performed |

Colon cancer | Not done | 10 days (after symptoms onset) |

|

| |||||||||

| [32] | 11, M | — | Visual loss | — | — | — | Burkitt's lymphoma | — | — |

|

| |||||||||

| [33] | 49, M | 1 month (symptoms-carcinomatosis) | Scotomas, diplopia | Headache, nausea and vomiting, and vertigo | CT scan (normal) | (1) Prot ↑, cell ↑ (2) MTC positive |

Gastric cancer | IT: MTX 20 mg | 60 days (after symptoms onset) |

|

| |||||||||

| [34] | 59, F | 39 months (carcinomatosis) | Bilateral blindness | Dizziness, tinnitus, and confusion | CT scan (normal) | (1) Prot ↑, MTC positive (2) Pprot ↑, MTC negative. (3) prot ↑, MTC negative. (4) glu ↓, prot ↑, MTC positive. |

Breast cancer | RT. IT: Ara-C (70 mg), dexamethasone. IV: 5-FU, vincristine, MTX. Oral: cyclophosphamide, prednisone | 4 years and 2 months (after cancer diagnosis), 9 months (after carcinomatosis diagnosis) |

| 49, F | 5 years and 3 months (carcinomatosis) | Bilateral blindness | — | CT scan (normal) | (1) Glu ↓, prot ↑, MTC positive (2) normal |

Breast cancer | RT. IT: Ara-C, corticosteroids | 5 years and 6 months (after cancer diagnosis), 3 months (after carcinomatosis diagnosis) | |

|

| |||||||||

| [35] | 53, F | Postmortem diagnosis (1 month after symptoms onset) |

Anisocoria, papilledema | Headache, hemiparesis, meningeal signs, and loss of consciousness | Subdural hematoma | Not performed | Gastric cancer | — | 26 days (after symptoms onset) |

|

| |||||||||

| [36] | 53, M | Postmortem diagnosis (3 months after symptoms onset) |

Blindness | Nausea, vomiting, confusion, ataxia, meningeal signs, and seizures | CT scan (normal) | (1) Cells ↑, prot ↑, glu ↓ (2) prot ↑ |

Lung cancer | Not done | 3 months (after symptoms onset) |

|

| |||||||||

| [37] | 59, F | 46 months (symptoms carcinomatosis); 10 months (carcinomatosis) | Scotomas, visual loss to blindness | Cerebellar ataxia | Skull radiography (normal) | (1) cells ↑, MTC positive (2) normal |

Anaplastic endometrioid sarcoma | RT. IT: MTX (20 mg × 4), IM: citrovorum factor |

60 days (after carcinomatosis diagnosis), 365 days (after cancer diagnosis) |

Cn: Cranial nerve; SIADH: syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion; SAH: subarachnoid Haemorrhage; GME: generalised meningeal enhancement; FME: focal enhancement; NHL: non Hodgkin lymphoma; ALL: acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML: acute myelocytic leukemia; IT: intrathecal; O: oral; IM: intramuscular.

Ocular symptoms were the presenting clinical feature in 34 out of 41 patients (83%) and were the only manifestation of meningeal carcinomatosis in 3 patients (7%). Visual loss was the presenting clinical manifestation in 17 patients (50%) and was the most common ocular symptom (70%). Visual loss was bilateral in 8 patients and unilateral in 2 patients. Sequential optic nerve involvement was observed in 5 patients. Three patients had sudden onset of blindness. Visual loss was progressive in other six patients.

Additional ocular manifestations were diplopia (18 patients, presenting manifestation in 16 patients), ptosis (8 patients), papilledema (4), anysocoria (3), exophthalmos (2), orbital pain (2), scotomas (2), hemianopsia (1), and nystagmus (1).

Other common symptoms were headache (24 patients), altered consciousness (10 patients), meningism (8 patients), hemiparesis (7), ataxia (7), dizziness (6), and seizures (4). V (4), VII (6), VIII (4), IX and X (2), and XII (1) cranial nerves involvement has also been reported.

Twenty-three patients underwent enhanced MRI which was diagnostic in 8 patients (35%). In 7 patients generalized meningeal enhancement was noted, and in 2 patients meningeal enhancement was associated with optic nerves enhancement, which was bilateral in 1 patient and unilateral in the other one. Three patients had cranial nerves enhancement, while isolated optic nerve enhancement was seen in only 1 patient (unilateral on the first MRI and bilateral at the second MRI). Other MRI findings included hydrocephalus (1), infarction of basal nuclei (1), and cerebellar enhancement (3).

8 patients had normal MRI findings.

All patients except five underwent CSF examination which was normal in 1 patient, and increased cells count was found in 11 patients (range: 9–598/mm3), increased protein levels were observed in 16 patients (range: 62–334 mg/dL), and decreased glucose levels were found in 8 patients (range: 5–43 mg/dL). Citology was positive in 29 patients (76%). The histology of the original tumor was highly variable with solid tumors being more frequently associated with meningeal carcinomatosis. The most common was gastric cancer followed by lymphoma, breast, and lung cancer.

16 patients underwent chemotherapy (see Table 1), and the mean life expectancy was 123 days (range 5–730 days). Autopsy was obtained in 13 patients. See Table 1.

5. Discussion

Meninigeal carcinomatosis occurs in 1–5% of solid tumors being adenocarcinoma the most common histology. The highest leptomeningeal diffusion rate has been reported for small cell lung cancer (11%) and melanoma (20%). Meningeal involvement occurs in about 5% of breast cancer patients [1]. Neoplastic meningitis is more likely to occur in patients with disseminated cancer, but in, respectively, 20% and 10% of cases it may manifest after a disease-free period or as a first manifestation of systemic tumors [2]. Current diagnostic methods are limited and may fail to identify MC early enough to prevent the escalation of neurological damage. Thus meningeal carcinomatosis should be included in the differential diagnosis in the presence of multifocal disease but also considered in the evaluation of isolated syndromes such as intracranial hypertension, cauda equine syndrome, or cranial neuropathy. The most common manifestation of cranial nerves involvement is diplopia due to VI cranial nerve palsy, followed by III and IV involvement. V, VIII, and optic nerve may also be affected [38].

Diagnostic workup includes CSF examination and neuroradiological studies. The presence of malignant cells in the CSF is diagnostic, other supportive features are increased opening pressure, pleocytosis, elevated proteins, and decreased glucose levels. CSF cytology may be negative in 65% of patients on initial examination, but only in 20% of patients on second lumbar puncture [2]. CSF increased levels of vascular endothelial growth factors have been proposed as a promising biomarker with a reported sensitivity of 51–100% and a specificity of 73–100% for leptomeningeal metastases [39].

Gadolinium-enhanced MRI is also useful for the diagnosis of meningeal carcinomatosis because enhancement on MRI will reveal any irritation of leptomeninges resulting in cranial nerves or intradural extramedullary enhancement on spinal MRI.

Ocular involvement represents a frequent manifestation of meningeal carcinomatosis. The reported frequency of ocular signs may be as high as 90% [40]. The present report is an updated and systematic review of ocular manifestations of neoplastic meningitis. Our data show that ocular symptoms often represent the first clinical manifestation of meningeal carcinomatosis (83%) and the only clinical manifestation in a small proportion of subjects (7%). For this reason it should be considered in the differential diagnosis even in the absence of associated clinical symptoms more suggestive of meningeal carcinomatosis such as headache (58%), altered consciousness (24%), meningism (19%), focal signs (34%), dizziness (15%), seizures (10%), and cranial nerves other than ocular involvement (32%). The most common ocular manifestation was visual loss (70%) followed by diplopia (41%), ptosis (19%), papilledema (10%), anysocoria (7%), exophthalmos (5%), orbital pain (5%), scotomas (5%), hemianopsia (2%) and nystagmus (2%). Gadolinium-enhanced MRI was diagnostic only in about one third of patients. Meningeal enhancement was detected in about one third of patients; in two of them (25%) it was associated with focal optic nerve enhancement. In one patient (12%) contrast-enhanced MRI revealed isolated optic nerve enhancement. CSF examination was abnormal in all (36) but one patient. The most common finding was increased proteins level (44%), increased cells count (30%), and decreased glucose (22%). Citology was positive in a high proportion of patients (76%) with solid tumors being the more frequent. The first CSF examination may be inconclusive, thus if clinical and radiological suspicion persist and cell count is increased, a repeated lumbar puncture is recommended.

6. Conclusion

Ocular involvement is a frequent and early clinical manifestation of meningeal carcinomatosis. Moreover clinicians should be aware that ocular involvement may mimic different diseases as shown in our case report, where neoplastic optic nerve involvement was indistinguishable from optic neuritis. Thus meningeal carcinomatosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of diplopia and visual loss in selected patients because diagnosis is often challenging.

Conflict of Interests

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

References

- 1.Chamberlain MC. Carcinomatous meningitis. Archives of Neurology. 1997;54(1):16–17. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550130008003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chamberlain MC. Neoplastic meningitis. Oncologist. 2008;13(9):967–977. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grossman SA, Krabak MJ. Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 1999;25(2):103–119. doi: 10.1053/ctrv.1999.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walz J. Ocular manifestations of meningeal carcinomatosis: a case report and literature review. Optometry. 2011;82(7):408–412. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller E, Dy I, Herzog T. Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer. Medical Oncology. 2012;29(3):2010–2015. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-0076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bulut G, Erden A, Karaca B, Göker E. Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis of gastric adenocarcinoma. Turkish Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011;22(2):195–198. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2011.0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arias M, Alberte-Woodward M, Arias S, Dapena D, Prieto Á, Suárez-Peñaranda JM. Primary malignant meningeal melanomatosis: a clinical, radiological and pathologic case study. Acta Neurologica Belgica. 2011;111(3):228–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Komiyama S, Nishio E, Torii Y, et al. A case of primary uterine cervical neuroendocrine tumor with meningeal carcinomatosis confirmed by diagnostic imaging and autopsy. International Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;16(5):581–586. doi: 10.1007/s10147-010-0155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butchart C, Dahle-Smith A, Bissett D, Mackenzie JM, Williams DJ. Isolated meningeal recurrence of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Case Reports in Oncology. 2010;3(2):171–175. doi: 10.1159/000315473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohnishi S, Dazai M, Iwasaki Y, Tsuzaka K, Takahashi T, Miyagishima T. Undiagnosed collecting duct carcinoma presenting as meningeal carcinomatosis and multiple bone metastases. Internal Medicine. 2010;49(15):1541–1544. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruce BB, Tehrani M, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Deafness and blindness as a presentation of colorectal meningeal carcinomatosis. Clinical Advances in Hematology and Oncology. 2010;8(8):564–566. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breivik KL, Laurini R, Steen R, Alstadhaug KB. A 61-year-old man with sciatica. Tidsskrift for den Norske Lægeforening. 2009;129(10):1000–1002. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.09.33160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaviani P, Silvani A, Corsini E, Erbetta A, Salmaggi A. Neoplastic meningitis from breast carcinoma with complete response to liposomal cytarabine: case report. Neurological Sciences. 2009;30(3):251–254. doi: 10.1007/s10072-009-0044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunning KK, Wudhikarn K, Safo A-O, Holman CJ, McKenna RW, Pambuccian SE. Adrenal extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration and cerebrospinal fluid cytology and immunophenotyping: a case report. Diagnostic Cytopathology. 2009;37(9):686–695. doi: 10.1002/dc.21077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamada T, Furukawa K, Yokoi K, Ohaki Y, Okada S, Tajiri T. A case of meningeal carcinomatosis with gastric cancer which manifested meningeal signs as the initial symptom; the palliative benefit of radiotherapy. Journal of Nippon Medical School. 2008;75(4):216–220. doi: 10.1272/jnms.75.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Portera CC, Gottesman RF, Srodon M, Asrari F, Dillon M, Armstrong DK. Optic neuropathy from metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: an unusual CNS presentation. Gynecologic Oncology. 2006;102(1):121–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nardone R, Herz M, Egarter-Vigl E, Tezzon F. Isolated oculomotor nerve palsy as the presenting clinical manifestation of a meningeal carcinomatosis: a case report. Neurological Sciences. 2006;27(4):288–290. doi: 10.1007/s10072-006-0687-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gokce M. Analysis of isolated cranial nerve manifestations in patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2005;12(8):882–885. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy J, Marcus M, Shelef I, Lifshitz T. Acute bilateral blindness in meningeal carcinomatosis. Eye. 2004;18(2):206–208. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sato Y, Ohta Y, Kaji M, Oizumi K, Kaji M. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 in cerebrospinal fluid and within malignant cells in a case of leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1998;65(3):402–403. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.65.3.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mouallem M, Ela N, Segal-Lieberman G. Meningeal carcinomatosis and syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone in a patient with metastatic carcinoma of the stomach. Southern Medical Journal. 1998;91(11):1076–1078. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199811000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McFadzean R, Brosnahan D, Doyle D, Going J, Hadley D, Lee W. A diagnostic quartet in leptomeningeal infiltration of the optic nerve sheath. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. 1994;14(3):175–182. doi: 10.3109/01658109409024045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tans RJJ, Koudstaal J, Koehler PJ. Meningeal carcinomatosis as presenting symptom of a gallbladder carcinoma. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 1993;95(3):253–256. doi: 10.1016/0303-8467(93)90133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neetens A, Clemens A, van den Ende P, de Bock R, Neetens I. Optic neuritis in non Hodgkin lymphomas. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 1992;200(5):525–528. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1045815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teare JP, Whitehead M, Rake MO, Coker RJ. Rapid onset of blindness due to meningeal carcinomatosis from an oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 1991;67(792):909–911. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.67.792.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sato Y, Ohta Y, Ohtsuka T, Shoji H, Oizumi K. A case of leptomeningeal carcinomatosis: demonstration of CA19-9 and CEA positive malignant cells in the CSF and particular elevation of CA19-9 level in the CSF. Rinshō Shinkeigaku. 1991;31(2):175–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boogerd W, Moffie D, Smets LA. Early blindness and coma during intrathecal chemotherapy for meningeal carcinomatosis. Cancer. 1990;65(3):452–457. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900201)65:3<452::aid-cncr2820650313>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watanabe A, Mizobe M, Ogawa Y, et al. A case of long-term survival of a patient with complicated diffuse metastatic leptomeningeal carcinomatosis secondary to lung adenocarcinoma. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1990;28(8):1130–1135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCrary JA, III, Patrinely JR, Font RL. Progressive blindness caused by metastatic occult signet-ring cell gastric carcinoma. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1986;104(3):410–413. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050150110039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Usui N, Ogawa M, Inagaki J, et al. Case report of meningeal carcinomatosis of gastric cancer successfully treated with intrathecal and systemic chemotherapy. Gan to Kagaku Ryoho. 1985;12(1):155–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohkawa H, Nakazawa K, Nakada K, Miyauchi J. Carcinoma of the colon associated with diffuse metastatic leptomeningeal carcinomatosis (DMLC) presenting as disturbance of consciousness—a case report. Gan No Rinsho. 1984;30(4):409–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donoso LA, Magargal LE, Eiferman RA. Meningeal carcinomatosis secondary to malignant lymphoma (Burkitt’s pattern) Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 1981;18(1):48–50. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19810101-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agnelli G, Gresele P. Mucus-secreting ‘signet-ring’ cells in CSF revealing the site of primary cancer. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 1980;56(662):868–870. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.56.662.868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cantillo R, Jain J, Singhakowinta A, Vaitkevicius VK. Blindness as initial manifestation of meningeal carcinomatosis in breast cancer. Cancer. 1979;44(2):755–757. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197908)44:2<755::aid-cncr2820440249>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakaki S, Mori Y, Matsuoka K, Ohnishi T, Bitoh S. Metastatic dural carcinomatosis secondary to gastric cancer. Neurologia Medico-Chirurgica. 1979;19(1):39–44. doi: 10.2176/nmc.19.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Appen RE, de Venecia G, Selliken JH, Giles LT. Meningeal carcinomatosis with blindness. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1978;86(5):661–665. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(78)90186-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Altrocchi PH, Eckman PB. Meningeal carcinomatosis and blindness. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1973;36(2):206–210. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.36.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balm M, Hammack J. Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis: presenting features and prognostic factors. Archives of Neurology. 1996;53(7):626–632. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550070064013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deisenhammer F, Egg R, Giovannoni G, et al. EFNS guidelines on disease-specific CSF investigations. European Journal of Neurology. 2009;16(6):760–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wasserstrom WR, Glass JP, Posner JB. Diagnosis and treatment of leptomeningeal metastases from solid tumors: experience with 90 patients. Cancer. 1982;49(4):759–772. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820215)49:4<759::aid-cncr2820490427>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]