INTRODUCTION

As many as 40% of ischemic strokes are without a determined cause and are considered “cryptogenic”[1]. Many cardiac abnormalities have been implicated in cryptogenic strokes, including patent foramen ovale[2], atrial septal aneurysm[3], and undetected intermittent atrial fibrillation[4]. However, cryptogenic strokes often occur in the absence of these abnormalities. In 2010, Krishnan and Salazar described the left atrial septal pouch (LASP)[5], an anatomic variant of the interatrial septum that may be a nidus for thrombus formation. We report a case of cryptogenic stroke in the setting of LASP.

CLINICAL CASE

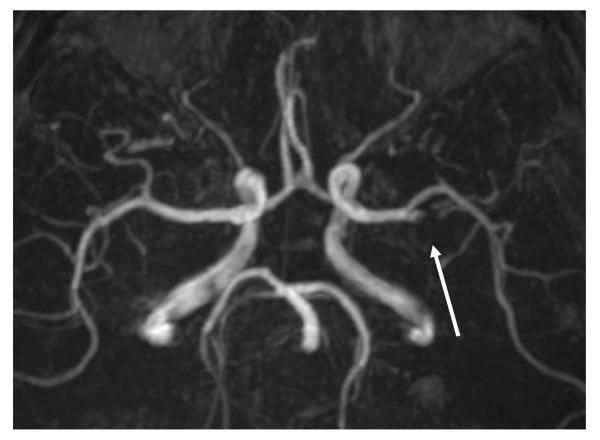

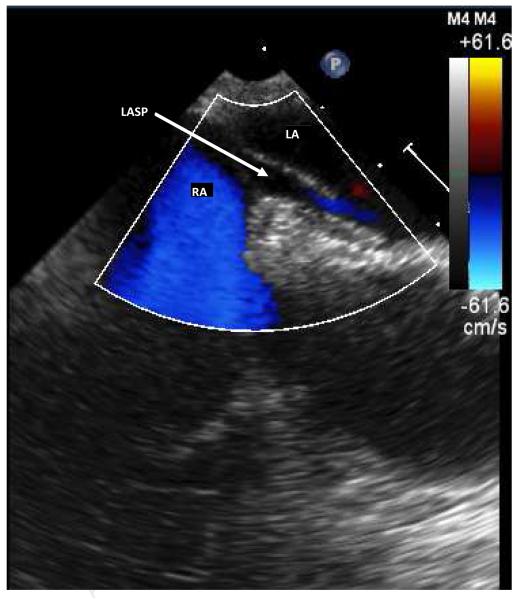

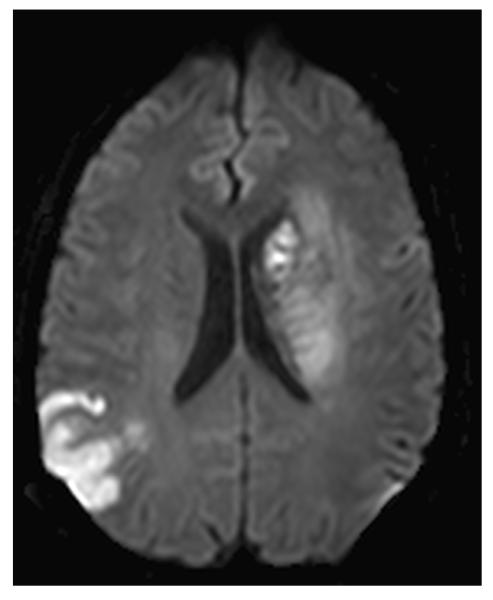

A 49 year-old right-handed man was admitted to UC Irvine Medical Center because of right hemiplegia, right-sided sensory symptoms, and slurred speech. He was not a candidate for intravenous tissue type plasminogen activator because he presented outside of the therapeutic time window. Past medical history was remarkable for bilateral subdural hematomas that were evacuated without sequela two years previously. He had no known vascular risk factors, including no hypertension or diabetes mellitus. Findings on examination included flaccid right hemiplegia. Laboratory work-up showed low-density lipoprotein level of 158 mg/dl. Electrocardiography revealed sinus rhythm with an intraventricular conduction delay, and cardiac monitoring performed for nearly two weeks showed no additional findings including no atrial fibrillation. Initial head CT showed no acute intracranial abnormalities, and there were no hyperdense vessels. MRI of the brain demonstrated large acute left basal ganglia infarct, along with an additional small acute infarct in the left postcentral gyrus. CT angiography and magnetic resonance angiography (Figure 1a) revealed focal occlusion of left middle cerebral artery (MCA) genu; carotid and vertebral arteries demonstrated no significant stenosis or dissection. Thrombophilia panel, including anti-thrombin III levels, lupus anticoagulant, factor V Leiden, and protein C activity did not identify any abnormalities. Transthoracic echocardiogram was normal with a negative bubble study with and without valsalva maneuver. Transesophageal echocardiogram findings included a negative bubble study with and without valsalva and no evidence of left atrial thrombus. However, a prominent LASP was visualized (Figure 1b). Aspirin and atorvastatin were started for secondary stroke prophylaxis. Nine days after admission, the patient experienced an apparent seizure (while remaining in sinus rhythm) and repeat MRI of the brain identified a new acute infarct involving the posterior right temporal-parietal region and right occipital lobe (Figure 1c). The largest area measured 3.7cm (anteroposterior) × 3cm (transverse). He was later admitted to the rehabilitation service and discharged 5 weeks later with no further strokes.

1a.

Magnetic resonance angiogram of the head showing occlusion of the proximal inferior left M2 division of middle cerebral artery. A meniscus sign (arrow) is seen, suggesting clot.

1b.

Transesophageal echocardiogram showing color flow into the left atrial septal pouch. LASP = left atrial septal pouch, RA= right atrium, LA = left atrium.

1c.

Diffusion-weighted MRI after the second stroke, showing the acute right temporal-parietal infarct and subacute left basal ganglia infarct with mild swelling.

DISCUSSION

Our patient experienced bi-hemispheric ischemic strokes, with the two strokes occurring over the course of ten days. The imaging studies demonstrated involvement of the bilateral arterial territories with the presence of an intraluminal thrombus and absence of other findings, suggesting multiple embolic episodes. LASP was identified by transesophageal echocardiography, and no other embolic source was identified. Prior case reports have identified LASP in patients with transient ischemic attacks and with thrombi along the left atrial septum [6-8], and we suggest in this patient that LASP was a likely cause of stroke.

LASP is formed when the interatrial septa fuse incompletely at birth, creating a blind-ending pouch that communicates exclusively with the left atrium [5]. Anatomy of LASP may promote blood stasis and thrombus formation. A case-control study reported no association between LASP and cryptogenic strokes, but the average age of patients in that study was 71 years [9]. In the current case, patent foramen ovale and atrial septal aneurysm were absent and cardiac monitoring and EKG showed no arrhythmia. Further study of possible association of LASP with ischemic stroke in young patients may be warranted.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by NIH NS20989

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Amarenco P. Underlying pathology of stroke of unknown cause (cryptogenic stroke) Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27(Suppl 1):97–103. doi: 10.1159/000200446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lamy C, Giannesini C, Zuber M, Arquizan C, Meder JF, Trystram D, et al. Clinical and imaging findings in cryptogenic stroke patients with and without patent foramen ovale: the PFO-ASA Study. Atrial Septal Aneurysm. Stroke. 2002;33:706–11. doi: 10.1161/hs0302.104543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cabanes L, Mas JL, Cohen A, Amarenco P, Cabanes PA, Oubary P, et al. Atrial septal aneurysm and patent foramen ovale as risk factors for cryptogenic stroke in patients less than 55 years of age. A study using transesophageal echocardiography. Stroke. 1993;24:1865–73. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.12.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Seet RC, Friedman PA, Rabinstein AA. Prolonged rhythm monitoring for the detection of occult paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in ischemic stroke of unknown cause. Circulation. 2011;124:477–86. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.029801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Krishnan SC, Salazar M. Septal pouch in the left atrium: a new anatomical entity with potential for embolic complications. JACC Cardiovascular Interventions. 2010;3:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hameed A, Akhter MW, Bitar F, Khan SA, Sarma R, Goodwin TM, et al. Left atrial thrombosis in pregnant women with mitral stenosis and sinus rhythm. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;193:501–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Breithardt OA, Papavassiliu T, Borggrefe M. A coronary embolus originating from the interatrial septum. European Heart Journal. 2006;27:2745. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gurudevan SV, Shah H, Tolstrup K, Siegel R, Krishnan SC. Septal thrombus in the left atrium: is the left atrial septal pouch the culprit? JACC Cardiovascular Imaging. 2010;3:1284–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tugcu A, Okajima K, Jin Z, Rundek T, Homma S, Sacco RL, et al. Septal pouch in the left atrium and risk of ischemic stroke. JACC Cardiovascular Imaging. 2010;3:1276–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]