A 16-year-old girl presented with dysphagia and heartburn for 10 years. She was diagnosed with Gillespie syndrome at the age of 1 year. Neurologic findings were represented by bilateral aniridia, strabismus, ataxia and cognitive impairment. Karyotype was normal (46, XX).

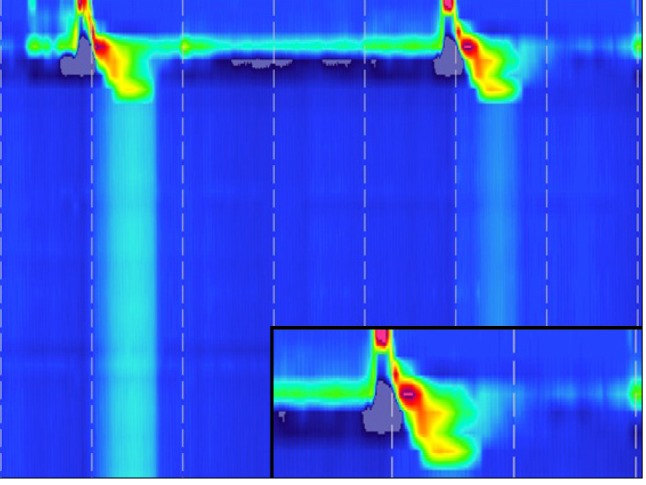

The upper digestive endoscopy disclosed an esophageal dilation and a 5 cm sized Barrett's esophagus confirmed by biopsy. High-resolution manometry showed aperistalsis and a non-detectable lower esophageal sphincter due to severe hypotonia (Figure), corresponding to absent peristalsis on the Chicago classification.1 Ambulatory 24 hours pH monitoring disclosed a pathological acid reflux (total % time pH < 4: 36%, DeMeester score = 149).

Figure.

High-resolution manometry showing aperistalsis and a non-detected lower esophageal sphincter due to severe hypotonia.

Gillespie syndrome is a very rare disease described firstly in 1965. It is defined by the triad of cerebellar ataxia, aniridia and mental deficiency.2 Associated manifestations have been infrequently described.3,4 However, esophageal involvement has never been reported.

Although the presented association between Gillespie syndrome and esophageal dysmotility may be incidental, there is also a possibility that esophageal dysmotility could be a true sign of Gillespie syndrome. We consider Frizzled 4 gene could be related with both conditions. Frizzled 4 gene is expressed in cerebellar Purkinje cells, esophageal skeletal muscle and cochlear inner hair cells and the targeted deletion of this gene in rats exhibited distinct defects such as absence of a skeletal muscle sheath around the lower esophagus associated with progressive esophageal distension and dysfunction.5

Footnotes

Financial support: None.

Conflicts of interest: None.

Author contributions: BDC: conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, and final approval of the version to be published. DTR: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, and final approval of the version to be published. LCS: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. FAMH: conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, and final approval of the version to be published.

References

- 1.Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, Kahrilas PJ, et al. Chicago classification criteria of esophageal motility disorders defined in high resolution esophageal pressure topography. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24(suppl 1):57–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01834.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gillespie FD. Aniridia, cerebellar ataxia, and oligophrenia in siblings. Arch Ophthalmol. 1965;73:338–341. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1965.00970030340008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wittig EO, Moreira CA, Freire-Maia N, Vianna-Morgante AM. Partial aniridia, cerebellar ataxia, and mental deficiency (Gillespie syndrome) in two brothers. Am J Med Genet. 1988;30:703–708. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320300302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luquetti DV, Oliveira-Sobrinho RP, Gil-da-Silva-Lopes VL. Gillespie syndrome: additional findings and parental consanguinity. Ophthalmic Genet. 2007;28:89–93. doi: 10.1080/13816810701209495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Huso D, Cahill H, Ryugo D, Nathans J. Progressive cerebellar, auditory, and esophageal dysfunction caused by targeted disruption of the frizzled-4 gene. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4761–4771. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04761.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]