Abstract

Objectives

To study the outcome of various hysterectomies in 2 years 1996 (N =10110) and 2006 (N=5279). The hypothesis was that the change in operative practices in 10 years has resulted in improvements.

Design

2 prospective nationwide cohort evaluations with the same questionnaire.

Setting

All national operative hospitals in Finland.

Participants

Patients scheduled to either abdominal hysterectomy (AH), vaginal hysterectomy (VH) or laparoscopic hysterectomy (LH) for benign disease.

Outcome measures

Patients’ characteristics, surgery-related details and complications (organ injury, infection, venous thromboembolism and haemorrhage).

Results

The overall complication rates fell in LH and markedly in VH (from 22.2% to 11.7%, p<0.001). The overall surgery-related infectious morbidity decreased in all groups and significantly in VH (from 12.3% to 5.2%, p<0.001) and AH (from 9.9% to 7.7%, p<0.05). The incidence of bowel lesions in VH sank from 0.5% to 0.1% and of ureter lesions in LH from 1.1% to 0.3%. In 2006 there were no deaths compared with three in 1996.

Conclusions

The rate of postoperative complications fell markedly in the decade from 1996 to 2006. This parallels with the recommendation of the recent meta-analyses by Cochrane collaboration; the order of preference of hysterectomies was for the first time precisely followed in this nationwide study.

Trial registration

The 2006 study was registered in the Clinical Trials of Protocol Registration System Data (NCT00744172).

Keywords: Gynaecology

Article summary.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The strength of the study is that it is prospective and nationwide and spans a time frame of 10 years.

Participation was anonymous and voluntary.

The limitations are the difference of the background of the study populations in 1996 and 2006, and data coverage (79%) in 2006. Differences is study populations cannot be corrected for, but any selection bias in the population was checked by analysis of data in the national register of the Patient Insurance Center in Finland.

Post-study evaluation showed that the complication rates were similar for non-participants and for participants.

Introduction

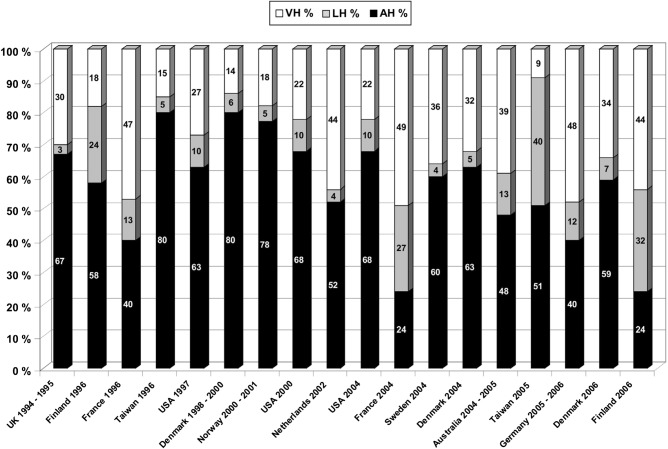

With the advent of laparoscopic hysterectomy (LH) in the late 1980s1 the role of vaginal hysterectomy (VH) and abdominal hysterectomy (AH) has been a matter of re-evaluation. The rate of AHs has subsequently fallen in some countries2–6 but AH still predominates in many countries as the main method for hysterectomy (figure 1).4–17 Along with these changes, the attitudes have, however, gradually changed in favour of VH and LH, which present themselves as less traumatising procedures than AH.

Figure 1.

Proportions of abdominal, vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomies in various countries from 1994 to 2006. Figures from France represent samples from University clinics only, otherwise national data are presented, apart from the UK, which excludes Wales, and represents 45% of national hysterectomies. References: UK 1994–1995, 7 Finland 1996, 8 France 1996, 9 Taiwan 1996,5 USA 1997,10 Denmark 1998-2000, 11 Norway 2000-2001, 12 USA 2000,2004, 13 Netherlands 2002,14 France 2004, 9 Sweden 2004,15 Denmark 2004, 4 Australia 2005-2005, 16 Taiwan 2005,5 Germany,17 Denmark 2006, 4 and Finland 2006.6

More than 20 years ago a systematic follow-up of the advantages and disadvantages of the then novel laparoscopic method for performing a hysterectomy would have been scientifically and clinically very much in order. However, the opportunity of collecting valuable pioneering data on the benefits and disadvantages of LH in comparison to the established methods (VH and AH) was never grasped. In Finland, a nationwide study on the morbidity related to AH, VH and LH for benign conditions was conducted in 1996.8 Not surprisingly, the most modern method, LH, was, at that time, associated with more severe complications than the other methods. The rate of complications stood also in proportion to the experience of the surgeons—the more experienced the surgeon, the lesser the LH-associated complications.

Since the beginning of the 2000s, several smaller studies, hospital-based series of LHs2 and randomised controlled trials (RCTs)18 19 have been published. Cochrane meta-analysis recommended VH as the primary technique for a hysterectomy, followed by LH when appropriate.20 21 There are, however, no longitudinal follow-up studies on the results of hospital-based or nationwide studies on patients undergoing a hysterectomy. Such studies are not only scientifically important but they also constitute important measures of quality control and are, as such, badly needed to help us to understand what we have learned of the different approaches to hysterectomy during all these years.22 We conducted a nationwide survey on the outcomes of hysterectomies of two cohorts first in 1996 and second in 2006. In this paper we compare the results after AH, VH and LH for benign conditions in 20066 with the results 10 years previously.8

Methods

Information on all hysterectomies performed for benign conditions in Finland was prospectively registered from 1 January to 31 December 2006, by the operating gynaecologist.6 Data collection was nationwide and followed the same procedure as in the survey 10 years previously, the FINHYST 1996 study.8 A dedicated form (FINHYST 2006) was used to collect data on preoperative, peroperative and postoperative events and operation-related morbidity during the patients’ hospital stay and convalescence. Severe organ complications were defined as injuries to the bladder, ureter and/or bowel. All 53 hospitals that participated were Finnish and produced 5324 forms, 45 of which were censored, usually because the final diagnosis was a malignant condition. The final data set consisted thus of 5279 hysterectomies; this covers 79.4% of all hysterectomies for a benign condition (5279/6645) reported to the National Hospital Discharge Register. In the FINHYST 1996 study, the cohort coverage was higher (92.1%, N=10 110) and the number of participating hospitals was 60 at that time.

Consistency of the data and missing information were thoroughly reviewed. The hysterectomies were divided into three groups: AH, VH and LH.23 To facilitate comparisons between the data sets in 1996 and 2006, each patient was defined as having had a complication or not having had one. Categorical data were analysed by the χ2 test or Fisher's exact probability test, and the means of continuous variables were analysed pair wise with Student's t test. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. All calculations were performed with the SPSS V.17.0 software.

Results

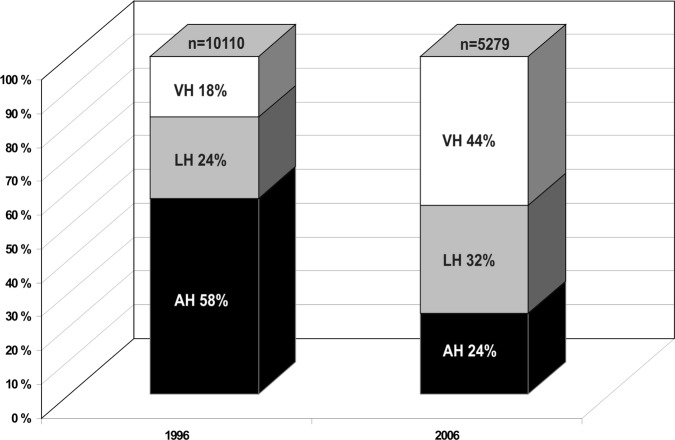

The proportions of VH and LH in Finland increased markedly in the decade 1996–2006, while the proportion of AH fell to less than half (figure 2). At the same time, the proportion of the less invasive hysterectomies, LH and VH, had surpassed AH in all hospitals and the overall number of hysterectomies dwindled from 10 110 to 5279 (reduction of 47.8%). In 2006, 1.7% of all hysterectomies were subtotal and in 1996, 7.3%. In 2006, the most common indication for AH was fibroids 58% (in 1996, 67%), for VH uterine prolapse 61% (in 1996, 83%) and for LH fibroids 39% (in 1996, 56%) and menorrhagia 30% (in 1996, 47%).

Figure 2.

Proportion of hysterectomies by type in Finland in 1996 and 2006. AH, abdominal hysterectomy; VH, vaginal hysterectomy; LH, laparoscopic hysterectomy.

In 2006 hysterectomy was performed on significantly older patients in the AH and LH groups but younger in the VH group compared with 1996 (table 1). Also, the mean body mass index had increased significantly in the AH and LH groups but not in the VH group. The average uterine weight had risen significantly in all groups, most in the AH group, while the duration of the operation decreased significantly for LH and for VH, but increased for AH. Perioperative haemorrhage in VH decreased significantly and increased in AH and LH but not significantly in LH. In all groups the duration of the hospital stay was significantly reduced, mostly in the VH group. The convalescence period decreased significantly in the AH and VH groups but increased slightly in the LH group (table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and surgery-related details (mean±SD) by hysterectomy method in 1996 and 2006

| Abdominal |

Vaginal |

Laparoscopic |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 (N=5875) |

2006 (N=1255) |

1996 (N=1801) |

2006 (N=2345) |

1996 (N=2434) |

2006 (N=1679) |

|||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age | 48.8 | 8.7 | 50.1 | 8.8 | 58.6 | 13.2 | 55.0 | 11.8 | 47.0 | 7.5 | 49.2 | 8.5 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.3 | 4.5 | 27.1 | 5.3 | 26.3 | 3.9 | 26.4 | 4.4 | 24.9 | 3.9 | 26.1 | 4.6 |

| Operation time (min) | 86 | 31 | 93 | 37 | 88 | 32 | 78 | 33 | 124 | 48 | 108 | 43 |

| Haemorrhage (mL) | 305 | 312 | 355 | 360 | 342 | 353 | 203 | 269 | 262 | 271 | 270 | 669 |

| Uterine weight (g) | 290 | 302 | 433 | 425 | 109 | 84 | 131 | 110 | 195 | 108 | 210 | 146 |

| Hospital stay (days) | 6.0 | 2.2 | 3.8 | 1.8 | 5.9 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 3.4 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.4 |

| Convalescence (days) | 34.4 | 5.3 | 32.3 | 4.6 | 34.0 | 8.8 | 29.4 | 8.0 | 21.5 | 8.8 | 22.0 | 6.3 |

All pairs (1996 vs 2006); p<0.001, except in LH for haemorrhage (p=0.603) and in VH for BMI (p=0.484).

BMI, body mass index; LH, laparoscopic hysterectomy; VH, vaginal hysterectomy.

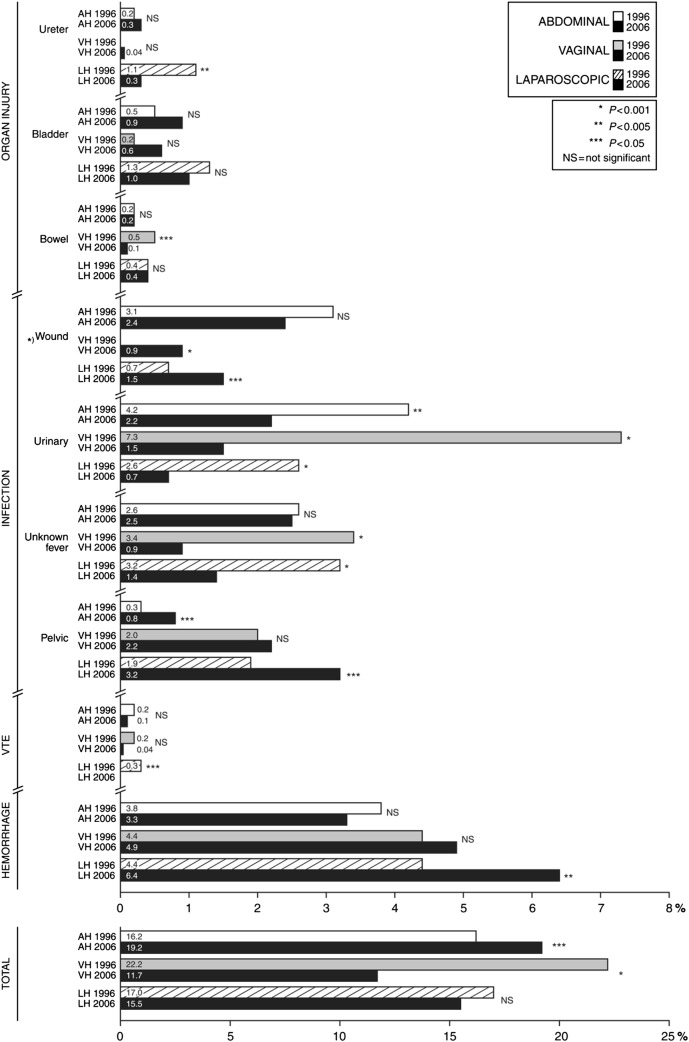

The overall complication rate related to any type of hysterectomy declined very significantly from 17.5% in 1996 to 14.7% in 2006 (p<0.001). The rate of complications in 1996 was 16.2% for AH, 22.2% for VH and 17% for LH. Ten years later there was a slight increase to 19.2% in complications among patients with AH (p<0.05) but a significant decrease to 11.7% in the VH (p<0.001) and a non-significant decrease to 15.5% in patients with LH. The overall occurrence of organ injuries was significantly reduced only in the LH group from 2.8% to 1.7% (p<0.05). Of the severe organ complications bowel injuries were significantly less common only in the VH group in 2006 as compared to1996 and there was no difference in this respect in the AH and LH groups (figure 3 or table 3). Similarly, ureter lesions occurred significantly less often only in the LH group in 2006 than in 1996.

Figure 3.

Complications related to abdominal, vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomies in 1996 and 2006. VTE, venous tromboembolism. *Pelvic infection data from 1996 comprise all intra-abdominal and vaginal infections, whereas in 2006 was late onset of pelvic infection was defined as pelvic abscess or hematoma. **N of patients. A patient may have had more than one complication (*) including vaginal cuff infection.

Table 3.

Rate and number of complications in various hysterectomies in 1996 and 2006

| Abdominal |

Vaginal |

Laparoscopic |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 (N=5875) |

2006 (N=1255) |

1996 (N=1801) |

2006 (N=2345) |

1996 (N=2434) |

2006 (N=1679) |

||||||||||

| Per cent | N | Per cent | N | p Value | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | p Value | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | p Value | |

| Organ injury | |||||||||||||||

| Ureter | 0.2 | 9 | 0.3 | 4 | 0.212 | – | 0 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.381 | 1.1 | 27 | 0.3 | 5 | 0.004 |

| Bladder | 0.5 | 29 | 0.9 | 11 | 0.099 | 0.2 | 4 | 0.6 | 14 | 0.069 | 1.3 | 31 | 1.0 | 17 | 0.443 |

| Bowel | 0.2 | 12 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.807 | 0.5 | 9 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.010 | 0.4 | 9 | 0.4 | 7 | 0.811 |

| Total/patient | 0.9 | 50 | 1.4 | 18 | 0.054 | 0.7 | 13 | 0.7 | 17 | 0.991 | 2.8 | 67 | 1.7 | 29 | 0.032 |

| Infection | |||||||||||||||

| Wound | 3.1 | 180 | 2.4 | 30 | 0.200 | 0.9 | 20 | <0.001 | 0.7 | 17 | 1.5 | 25 | 0.013 | ||

| Urinary | 4.2 | 245 | 2.2 | 28 | 0.001 | 7.3 | 129 | 1.5 | 36 | <0.001 | 2.6 | 63 | 0.7 | 11 | <0.001 |

| Unknown fever | 2.6 | 152 | 2.5 | 32 | 0.939 | 3.4 | 62 | 0.9 | 22 | <0.001 | 3.2 | 79 | 1.4 | 23 | <0.001 |

| Pelvic* | 0.3 | 19 | 0.8 | 10 | 0.017 | 2.0 | 36 | 2.2 | 51 | 0.695 | 1.9 | 47 | 3.2 | 54 | 0.009 |

| Total/patient† | 9.9 | 583 | 7.7 | 97 | 0.016 | 12.3 | 222 | 5.2 | 122 | <0.001 | 8.3 | 201 | 6.7 | 113 | 0.070 |

| Tromboemblic | 0.2 | 9 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.528 | 0.2 | 4 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.099 | 0.3 | 7 | – | 0 | 0.028 |

| Haemorrhage | 3.8 | 221 | 3.3 | 42 | 0.479 | 4.4 | 79 | 4.9 | 114 | 0.472 | 4.4 | 107 | 6.4 | 108 | 0.004 |

| Total/patient† | 16.2 | 952 | 19.2 | 241 | 0.010 | 22.2 | 400 | 11.7 | 275 | <0.001 | 17.0 | 413 | 15.4 | 258 | 0.172 |

*Pelvic infection data from 1996 comprise all intra-abdominal and vaginal infections, whereas in 2006 was defined as abscess or haematoma.

†Number of patients. A patient may have had more than one complication.

The use of antibiotic prophylaxis increased from 82.1% to 97.5% (p<0.001) in a decade, and also the selection of antibiotics changed. In 1996, metronidazole was given as a single prophylactic agent to 66.7% of all patients, but in 2006 to only 9.9%. In 2006, cefuroxime was the primary choice of antimicrobial agent alone or in combination with metronidazole for 82.1% but in 1996 only for 15.3%. There were concomitantly significant reductions in the overall rate of infections; in the AH group from 9.9% to 7.7% (p<0.05), in the VH group from 12.3% to 5.2% (p<0.001) but a non-significant change from 17% to 15.4% in the LH group.

Also, the use of pharmacological thrombosis prophylaxis had risen from 35.4% in 1996 to 64.8% in 2006 (p<0.001) and there was a concomitant reduction in venous thromboembolisms in all groups, which was significant in the LH group (figure 3 or table 3). In 2006, there were no surgery-related deaths, whereas in 1996 there was one death in each hysterectomy group. The occurrence of postoperative haemorrhage in the LH group increased significantly from 1996 to 2006 (figure 3).

The intraoperative detection of organ injuries in LH increased from 60% in 1996 to 75% in 2006. Postoperative ileus occurred at a similar rate in 1996 and 2006: AH 1% vs 0.6%, LH 0.3% vs 0.2% and VH 0.1% vs 0.2%. The incidence of urinary retention was significantly higher (p<0.001) in the VH group in 1996 (3.1%) than in 2006 (1.6%) while in the AH group it was 0.5% both in 1996 and 2006 and in the LH group 0.9% and 0.5% in 1996 and 2006, respectively.

By 2006 the percentage of surgeons with experience of more than 30 hysterectomies had risen most markedly among surgeons performing LH: from 62% in 1996 to 73% in 2006 while there was no change for VH (78% in 1996 and 76% in 2006) but for AH there was a sinking trend from 91% in 1996 to 75% in 2006. The experience of the surgeons was associated with the occurrence of organ injuries. Surgeons who had performed more than 30 hysterectomies in 1996, had significantly fewer ureter and bladder injuries, especially in the LH group, than the less experienced surgeons (table 2). The same was the case for bowel injuries in 1996 in the VH group. In 2006, these differences were no longer present.

Table 2.

Rate and number of ureter, bladder and bowel injuries in various hysterectomies in Finland in relation to surgeon's experience (more than 30 vs 30 or less than 30 hysterectomies) in 1996 and 2006

| Abdominal |

Vaginal |

Laparoscopic |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 (N=5875) |

2006 (N=1255) |

1996 (N=1801) |

2006 (N=2345) |

1996 (N=2434) |

2006 (N=1679) |

|||||||

| Per cent | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | |

| Ureter injury | ||||||||||||

| ≤30 | – | 0.4 | 1 | – | – | 2.2 | 20 | 0.3 | 1 | |||

| >30 | 0.2 | 9 | 0.3 | 3 | – | 0.04 | 1 | 0.5** | 7 | 0.2 | 3 | |

| Bladder injury | ||||||||||||

| ≤30 | – | 1.1 | 3 | – | 0.6 | 3 | 2.0 | 18 | 1.3 | 5 | ||

| >30 | 0.5 | 28 | 0.7 | 7 | 0.4 | 4 | 0.5 | 9 | 0.8* | 12 | 1.0 | 12 |

| Bowel injury | ||||||||||||

| ≤30 | – | – | 1.3 | 5 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.4 | 4 | 0.3 | 1 | ||

| >30 | 0.2 | 12 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.3* | 4 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.3 | 5 | 0.4 | 5 |

*p=0.05.

**p<0.001.

Other comparisons (≤30 vs >30): not significant.

Discussion

The role of LH compared to the traditional AH and VH has been debated ever since the laparoscopic technique was introduced. It has been argued that LH is associated with higher expenses, longer operation times and a higher rate of complications. Large and comprehensive RCTs have been badly needed to give answers to these questions. Such studies need to be very large, even to the point of being unfeasible, if they are to have sufficient statistical power.22 Furthermore, they would also need to be set up so that they discount the effect of the individual surgeon, the surgeon's experience and the effect of sophisticated surgical centres compared with ordinary hospitals. National registry-based observational surveys on large numbers of consecutive patients with prospective data collection are an alternative to cumbersome and, maybe, unrealistic RCTs and document effectiveness because they reflect clinical reality in the hands of the ‘average’ gynaecological surgeon.22 This alternative was chosen for the present nationwide study, which compares some clinical determinants related to hysterectomies (AH, VH and LH) and hysterectomy-related morbidity in 2006 with 1996 in Finland.

In the present study the growth of the popularity of VH was especially gratifying: the rate of VH increased from 18% in 1996 to 44% in 2006 (figure 2), while the total number of complications, operation time, haemorrhage and bowel lesions related to VH decreased. All this took place despite the fact that the patients in 2006 were younger and were operated on for uterine descent less frequently; circumstances claimed to pose more operative challenges and yield complications. We believe that the vaginal approach should be used whenever possible.

The rate of LH also increased (from 24% to 36%). The current rate of LHs in Finland is high as compared to our neighbouring Nordic countries (4–7%)4 12 15 and globally (figure 1). Worldwide, only Taiwan has a higher rate of LH, where the rate of LH has soared from 5% in 1996 to 40% in 2005.5 In consequence, we have a much lower rate of AH (24%) as compared to many other countries; for example, the USA (68%)13 and the other Nordic countries, such as Sweden (60%),15 Denmark (59%)4 and Norway (78%).12 According to a recent meta-analysis by the Cochrane collaboration, the order of preference of hysterectomies should be VH and LH followed by AH.21 This study shows that this is precisely the sequence of preferences followed in Finland.

The main finding of this study is that the overall complication rates related to VH and LH have decreased in Finland. Another important observation was that of the severe organ lesions; ureter complications related to LH—one of the main concerns in 19968—have decreased highly significantly (from 1.1% to 0.3%). This finding is in accordance with a retrospective nationwide registry study on the complications of LH, which reported a continuously decreasing trend from 1993 to 2005 in ureter injuries in Finland.24 Also, the fact that LH-related bladder complications sank from 1.3% to 1% supports the notion that surgeons doing this operation have steadily gained experience and are well aware of the need to avoid harming the bladder and ureters. The rate of VH-associated bowel complications also sank significantly (figure 3). For AH there was a slight increase in the occurrence of total complications (from 16% in 1996 to 19% in 2006), but this only reflects the fact that more severe and advanced cases required the abdominal approach in 2006.

The reduction in the number of infections (figure 3 or table 3), especially urinary tract infections, was probably due to the increased prophylactic use of antibiotics. The reduction of thromboembolic events is most likely due to a consequence of increased and appropriate use of thromboprophylaxis. The aim to reduce both of these complications was discussed already some 10 years ago at a consensus meeting with the members of the Society of Gynecological Surgery in Finland, and a unified, common prophylaxis management system with antibiotics and antithrombotics was introduced and implemented.25 Of the other Scandinavian countries infectious morbidity related to hysterectomies in Sweden in 2003–2006 was 12% for AH, 15% for LH and 9.9% for VH.26 Much lower rates were entered into the Danish hysterectomy database: in 2006 there were postoperative infections (excluding urinary tract infections) in only 2% of all hysterectomies.4

Data coverage is a limitation of our study. We believe that one of the main reasons for the fact that in the FINHYST 1996 study the cohort coverage was higher (92%) than in 2006 (79%) is related to the circumstance that the approval of the ethics committee in 1996 did not require us to collect the patients’ social security numbers. The survey in 2006 was run according to new regulations, which require that each patient provides full disclosure of her identity and written informed consent. Since all other facets of the studies and the data collection were identical between the two studies, these requirements remain the only explanatory variable for the reduced participation coverage. The lower recruitment in 2006 made us perform a type of data verification. We examined the data from the national register of the Patient Insurance Center, to which patients’ self-report complications, usually in pursuit of economical compensation. The rate of complications was similar among those who had been recruited to FINHYST 2006 and those who were unable to participate. This observation would exclude selection bias in our study cohort.

In 2006, as compared to 1996, our patients were proportionately older, more obese and had a higher uterine weight, but still the duration of hospital stay in all hysterectomy types and the operation time for LH and VH was reduced (table 1). Evidently, the need for hysterectomy will persist, but it will not be as high as in the late 1990s.27 28 The outlook is that hysterectomies will be safer than before. Recent indications for hysterectomies in Finland were more properly scrutinised and patients undergoing these procedures were more severely affected than a decade earlier. Of course, it would have been ideal to adjust the complication rates of the different types of hysterectomy by the population difference because the patients in the three groups: AH, VH and LH were very different in 1996 and 2006 but this was not possible. Consequently, a definite conclusion whether the improvements in some parameters are a result of real clinical improvement rather than just a change in the populations cannot be drawn. However, the very significant decrease in overall complication rate in all hysterectomies between 1996 and 2006 indicate that clinical improvement was real. Moreover, the overall maximum rates of the most severe organ injuries (bladder, ureter and bowel) in all types of hysterectomies in Finland were 0.7–2.8% in 1996 and 0.7–1.7% in 2006. This improvement is encouraging and similar trends have been reported in other countries.2 This positive development has taken place in a time of a markedly decreasing need for hysterectomies mostly as a consequence of many new and effective conservative treatments of various bleeding problems (hormonal intrauterine device, thermoablation, etc).

Since the introduction of LH in Finland in the 1990s, gynaecological surgeons have collaborated actively in clinical practice and training. This has resulted in a unified system of data collection for research and quality control. With the first FINHYST study in 1996 we identified matters needing improvement, after which practices were changed, training was increased and collaboration on a national level was implemented. As a consequence of this fruitful and collegial collaboration, hysterectomy-associated morbidity has decreased and patients are selected more appropriately for the traditional abdominal, vaginal or endoscopic route.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: TB, PH and JM participated in literature search and data analysis. TB and JM participated in preparing the figures and tables. All authors participated in study design, data interpretation and writing. Permissions: TB, PH, JS and JM. TB and PH participated in data collection.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The FINHYST 2006 study was approved by the ministry of social affairs and health (Dnro STM/606/2005), by the Helsinki University Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB) and by the ethics committee of the department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the Helsinki University Hospital (Dnro 457/E8/04). The 2006 study was registered in the Clinical Trials of Protocol Registration System Data (NCT00744172).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Reich H, DiCaprio J, McGlynn F. Laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Gynecol Surg 1989;5:213–16 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donnez O, Jadoul P, Squifflet J, et al. A series of 3190 laparoscopic hysterectomies for benign disease from 1990 to 2006: evaluation of complications compared with vaginal and abdominal procedures. BJOG 2009;116:492–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.David-Montefiore E, Rouzier R, Chapron C, et al. Surgical routes and complications of hysterectomy for benign disorders: a prospective observational study in French university hospitals. Hum Reprod 2007;22:260–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansen CT, Møller C, Daugbjerg J, et al. Establishment of a national Danish hysterectomy database: preliminary report on the first 13 425 hysterectomies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2008;87:546–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu M, Huang K, Long C, et al. Trends in various types of hysterectomy and distribution by patient age, surgeon age, and hospital accreditation: 10-year population-based study in Taiwan. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2010;17:612–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brummer TH, Jalkanen J, Fraser J, et al. FINHYST 2006—National prospective 1-year survey of 5 279 hysterectomies. Hum Reprod 2009;24:2515–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maresh MJA, Metcalfe MA, Mc Pherson K, et al. The VALUE national hysterectomy study: description of the patients and their surgery. BJOG 2002;109:302–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mäkinen J, Johansson J, Tomas C, et al. Morbidity of 10 110 hysterectomies by type of approach. Hum Reprod 2001;16:1473–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapron C, Laforest L, Ansquer Y, et al. Hysterectomy techniques used for benign pathologies: results of a French multicentre study. Hum Reprod 1999;14:2464–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farquhar C, Steiner C. Hysterectomy rates in the United States 1990–1997. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:229–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Møller C, Kehlet H, Utzon J, et al. Hysterectomy in Denmark. An analysis of postoperative hospitalisation, morbidity and readmission. Dan Med Bull 2002;49:353–7 (in Danish) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oma J. Which factors affect the choice of method for hysterectomy in benign disease. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2004;124:92–4 (in Norwegian) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Jamieson DJ, et al. Inpatient hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 2000–2004. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;198:34–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolkman W, Trimbos-Kemper T, Jansen F. Operative laparoscopy in the Netherlands: diffusion and acceptance. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2007;130:245–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Persson P, Hellborg T, Brynhildsen J, et al. Attitudes to mode of hysterectomy—a survey-based study among Swedish gynecologists. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2009;88:267–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill E, Graham M, Shelley J. Hysterectomy trends in Australia—between 2000/01 and 2004/05. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2010; 50:153–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stang A, Merrill RM, Kuss O. Nationwide rates of conversion from laparoscopic or vaginal hysterectomy to open abdominal hysterectomy in Germany. Eur J Epidemiol 2011; 26:125–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garry R, Fountain J, Mason S, et al. The eVALuate study: two parallel randomised trials, one comparing laparoscopic with abdominal hysterectomy, the other comparing laparoscopic with vaginal hysterectomy. BMJ 2004;328:129–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson N, Barlow D, Lethaby A, et al. Methods of hysterectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2005;330:1478–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson N, Barlow D, Lethaby A, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(2):CD003677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nieboer TE, Johnson N, Lethaby A, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(3):CD003677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Claerhout F, Deprest J. Laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign diseases. In: Thakar R Manyonda Ieds Best practice and research clinical obstetrics and gynaecology, hysterectomy. Elsevier, 2005;19:357–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kovac SR. Guidelines to determine the root of hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 1995;85:18–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brummer TH, Seppälä T, Härkki P. National learning curve of laparoscopic hysterectomy and trends in hysterectomy in Finland 2000–2005. Hum Reprod 2008;23:840–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.GKS The society of gynaecological surgery in Finland, webpage, in Finnish. Suositukset 2007 (recommendations). http://www.terveysportti.fi/kotisivut/sivut.koti?p_sivusto=434 (accessed on July 2012) (in Finnish)

- 26.Löfgren M, Poromaa IS, Stjerndahl JH, et al. Postoperative infections and antibiotic prophylaxis for hysterectomy in Sweden: a study by the Swedish National Register for Gynecologic Surgery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2004;83:1202–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts TE, Tsourapas A, Middleton LJ, et al. Hysterectomy, endometrial ablation, and levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) for treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding: cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ 2011;342:2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qvistad E, Langebrekke A. Should we recommend hysterectomy more often to premenopausal and climacteric women? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2011;90:811–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.