Abstract

Objective

To investigate the trends and the risk of developing type 1 diabetes in the offspring of Swedes and immigrants by specific parental migration background, age, sex and birth cohort.

Design

Registry-based cohort study.

Setting

Using Swedish nationwide data we analysed the risk of developing type 1 diabetes in 3 457 486 female and 3 641 304 male offspring between 0 and 30 years of age, born to native Swedes or immigrants and born and living in Sweden between 1969 and 2009. We estimated incidence rate ratios (IRRs) with 95% CIs using Poisson regression models. We further calculated age-standardised rates (ASRs) of type 1 diabetes, using the world population as standard.

Results

We observed a trend of increasing ASRs among offspring below 15 years of age born to native Swedes and a less evident increase among offspring of immigrants. We further observed a shift towards a younger age at diagnosis in younger birth cohorts in both groups of offspring.Compared with offspring of Swedes, children (0–14 years) and young adults (15–30 years) with one parent born abroad had an overall 30% and 15–20% lower IRR, respectively, after multivariable adjustment. The reduction in IRR was even greater among offspring of immigrants if both parents were born abroad. Analysis by specific parental region of birth revealed a 45–60% higher IRR among male and female offspring aged 0–30 years of Eastern Africa.

Conclusions

Parental country of birth and early exposures to environmental factors play an important role in the aetiology of type 1 diabetes.

Keywords: Type 1 Diabetes, Birth Cohort, Incidence, Migration, Sweden

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The nationwide cohort design, nearly complete follow-up of type 1 diabetes occurrence over 40 years and avoiding misclassification bias through using unique personal identification number assigned to all Swedish citizens.

A limitation with our study is the lack of specific International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes for type 1 diabetes in the earlier versions of ICD (ie, 8th and 9th version of ICD). However, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus is low in Sweden and most likely the majority of diabetes cases diagnosed before 30 years of age are coded as type 1 diabetes.

Introduction

The epidemic of type 1 diabetes is accelerating in many parts of the world with a large impact on the affected individual's life and also with great health economic consequences.1 There is a wide variation in the incidence of type 1 diabetes between countries, ranging from 0.1/100 000 person-years in China and Venezuela to more than 40/100 000 person-years in Sweden and Finland, respectively.2–4

The concordance rate of type 1 diabetes among monozygotic twins has been estimated to 27%.5 Thus, in the aetiology of type 1 diabetes, there is considerable room for influence of environmental factors acting on genetic predisposition. Investigating the occurrence of type 1 diabetes in immigrants and their offspring offers a unique possibility to explore and delineate the gene–environment interaction for the development of type 1 diabetes.

Over the past decades, a rapid rise in the incidence of type 1 diabetes among individuals below 15 years of age has been reported and also with a shift towards younger age at the onset.6 7 These studies, however, have not distinguished between individuals born to parents with different migration background. If offspring of immigrants, with varying genetic background, experience the same change in age at the onset as observed in the offspring of natives, the importance of early environmental exposures for the development of type 1 diabetes would be further supported. We recently reported a decreased risk of type 1 diabetes among the majority of immigrants in Sweden compared with native Swedes. We also observed a tendency towards a convergence of risks for type 1 diabetes between the offspring of immigrants as one group and native Swedes.8 Since immigrants and their offspring are a heterogeneous population, there is a need to explore if the risk of type 1 diabetes varies by specific parental country or region of birth.

In the present study, we used Swedish nationwide data collected over 40 years to investigate the trend and the risk of developing type 1 diabetes in offspring of immigrants by specific paternal and maternal migration background and by birth cohorts. Since the incidence of type 1 diabetes varies with sex and age,9 10 the analyses were stratified by offspring sex and age.

Methods

Database

We used information from a newly established, nationwide dataset—The Migration and Health Cohort (M&H Co),11 where data from national, longitudinal clinical, health and sociodemographic registries have been compiled. This database was built by individual record-linkage between more than 15 Swedish national registries to facilitate studies on diabetes, injuries, cancer, cardiovascular and psychiatric diseases among immigrants and their descendants in Sweden. The linkage was carried out using the personal identification number (PIN), which is uniquely assigned to each individual that have resided in Sweden for longer than 1 year since 1947.12 The data used in this study are part of the M&H Co, including: (1) The Swedish Total Population Register, which covers the entire population registration in Sweden and is updated on a daily basis. The register contains information on demographic variables, such as date and place of birth and data on emigration and immigration13; (2) The Cause of Death Register, which contains information on the date of death, the main and contributing causes of death14; (3) The National Patient Register, including the Inpatient Register. It was established in 1964 but with national coverage since 1987 covering 85–95% of all diagnostic data.15 Since 2001, the Patient Register includes information on all registered outpatient visits to specialist care and day visits to hospitals and covers about 80% of all visits to the specialised outpatient care.16 The Patient Register contains data on the main diagnosis and up to eight secondary diagnoses.15 16 (4) The Multi-Generation Register contains links between children and their parents through PINs for all Swedish inhabitants born after 1931 who were alive in 1960.17 (5) The National Population and Housing Censuses and longitudinal integration database for health insurance and labour market studies, contains data on socioeconomic, occupational and demographic variables.18 19

The linkages between the registers have been completed by Statistics Sweden and the National Board of Health and Welfare. To ensure confidentiality, the PINs have been replaced by person-unique serial numbers and a key code is kept at Statistics Sweden.

Study cohort

The study population comprised 3 794 477 (51.4%) males and 3 593 765 (48.6%) females between 0 and 30 years of age, born and living in Sweden any time between 1 January 1969 and 31 December 2009. We excluded individuals whose parents had unknown information on country of birth and all individuals who had a history of type 1 diabetes, before entry into the cohort. The final cohort included 7 098 790 individuals (3 641 304 (51.3%) males and 3 457 486 (48.7%) females) aged 0–30 years and born in Sweden.

Follow-up

The cohort members were followed from date of birth or 1 January 1969, whichever occurred last, until the date of diagnosis of type 1 diabetes according to the Swedish versions of International Classification of Disease (ICD-8: 250, 1969–1986; ICD-9: 250, 1987–1996; ICD-10: E10, 1997 and onwards), emigration, death or end of follow-up (31 December 2009), whichever occurred first. Every individual in the cohort were followed for maximum 30 years of age.

Since earlier versions of ICD (ie, 8th and 9th version of ICD) could not distinguish between different types of diabetes, we have performed sensitivity analysis using ICD-10 only where we could identify type I diabetes (see method for details).

Classification of offspring based on parental country of birth

The cohort was divided into four groups according to parental country of birth: individuals with mothers born outside Sweden (father could be born in Sweden, abroad or unknown; n=345 827); individuals with fathers born outside Sweden (mother could be born in Sweden, abroad or unknown; n=317 397); individuals with both parents born outside of Sweden (n=435 045) and individuals with both parents born in Sweden (n=6 000 521). We also classified parental country of birth into six continents: Africa (North, South, East, West and Middle Africa), Asia (East, West, South Central and South East Asia), Europe (North, South, East and West Europe), Latin America (Caribbean, Central America and South America) Northern America and Oceania (Australia/New Zealand, Melanesia and Micronesia/Polynesia). Based on the findings from our previous study among immigrant individuals,8 we categorised Africa into North, East and West Africa; Europe into Finland, North Europe without Finland and South, East and West Europe (the latter three as one group). For the trend and the birth cohort analyses, we pooled all offspring of immigrants into one group.

Statistical analysis

We estimated incidence rate ratios (IRRs) with 95% CIs using Poisson regression models. The analyses were adjusted for age at follow-up (in 5 years intervals 0–4, 5–9, 10–14, 15–19, 20–24 and 25–30 years), calendar years of follow-up (four categories: 1969–1978, 1979–1988, 1989–1998 and 1999–2009) and education of the mother or father (classified into four levels: 0–9 years, 10–12 years, 13 years or more and unknown). All analyses were performed separately for females and males. In addition, analyses were made separately for children (0–14 years) and young adults (15–30 years) where we did not distinguish specific parental region or country of birth. In further analyses, children and young adults (0–30 years) were pooled together as one category to allow reasonable statistical power for analyses by specific maternal and paternal regions or country of birth to test the hypothesis that the mother's and the father's background would affect the offspring's risk of type 1 diabetes differently. We also analysed the risk of type 1 diabetes in children with the mother as well as the father born in the same country/region. Those with parents from different regions or from Sweden were categorised as a mixed group.

Since we had no specific ICD codes before 1997 to distinguish between types 1 and 2 diabetes, we repeated the analysis and confined our cohort to individuals living in Sweden between 1997 and 2009 where we could strictly identify type 1 diabetes according to ICD-10.

For the trend analysis, we further calculated age-standardised rates (ASRs), by parental migration background for both children (0–14 years) and young adults (15–30 years), by dividing number of new cases with the estimated numbers of person-years at risk in 5-years age categories using the world population as standard.20 ASRs were directly calculated to ensure comparability and to adjust for differences in age in the study population, in each of the age groups 0–4, 5–9, 10–14, 15–19, 20–24 and 25–30 years. We reported ASR in unit of per 100 000 person-years.

The Joint point regression analyses were performed to evaluate trends of type 1 diabetes in offspring to immigrants as well as offspring to Swedes and in both age groups.21 22 Annual per cent change (APC) was estimated to describe and test the statistical significance of the trends. The null hypothesis in this analysis is that the trend in incidence rates is the same over time. We used Statistical Analysis System (SAS) V.9.3 for all the analysis.

Results

On average, the age of onset of type 1 diabetes was similar in offspring of immigrants as in offspring of Swedes (mean±SD; offspring of immigrants 14.31±7.70, offspring of Swedes 15.47±7.99).

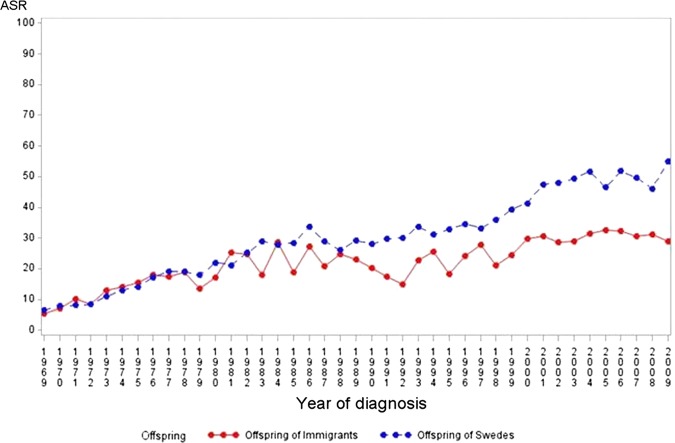

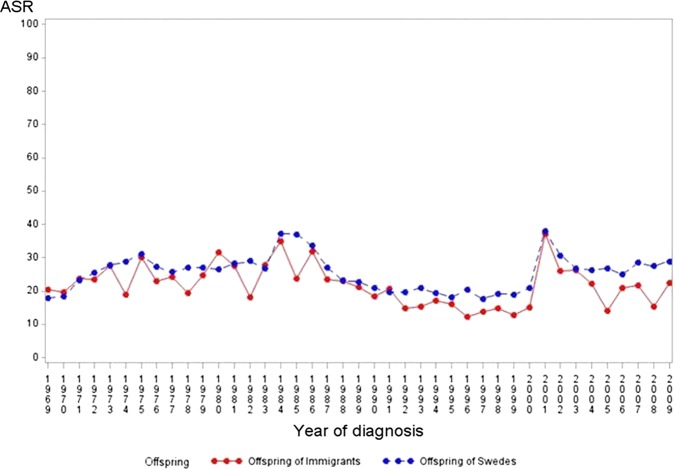

Over the study period (1969–2009), we observed a significant increasing trend for incidence of type 1 diabetes based on joint point regression analyses among offspring below 15 years of age born to native Swedes and to immigrants (offspring to Swedes: APC=3.9, p value <0.001 and offspring to immigrants: APC=2.2, p value<0.001 figure 1). In contrast, no increase or a slight decreasing trend was observed among young individuals between 15 and 30 years of age regardless of parental migration background (offspring to Swedes: APC=−0.0, p=0.9 and offspring to immigrants: APC=−0.7, p value =0.08, figure 2).

Figure 1.

Age-standardised type 1 diabetes incidence rate per 100 000 person-years (age-standardised rates) among offspring of Swedes and of immigrants in the age group (0–14), 1969–2009, Sweden.

Figure 2.

Age-standardized type 1 diabetes incidence rate per 100 000 person-years (age-standardised rates) among offspring of Swedes and of immigrants in the age group (15–30), 1969–2009, Sweden.

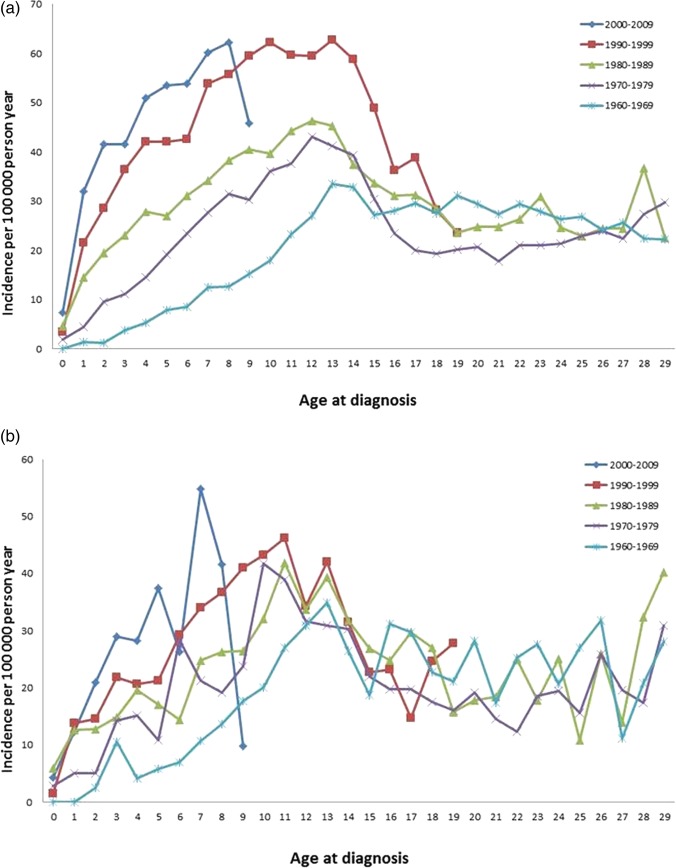

The birth cohort analysis revealed a shift towards lower age at onset in individuals below 15 years of age in both offspring of Swedes and in offspring of immigrants (figure 3A,B).

Figure 3.

Incidence of type 1 diabetes by age at diagnosis (0–30 years) and birth cohorts 1960–2009 among offspring of Swedes in Sweden (A) and immigrants in Sweden (B).

As compared to offspring of Swedish-born parents, boys and girls (0–14 years) with a foreign-born mother or father had about 30% lower IRR in the multivariable analyses adjusted for age, calendar period and parental education. Among boys and girls with both parents born abroad, corresponding risk reductions were about a 40% (table 1). The results from the sensitivity analysis, where we repeated the analysis and confined our cohort to individuals born in Sweden between 1997 and 2009, were similar to the results of the entire cohort (see online supplementary table S1).

Table 1.

Incidence rate ratio (IRR) and 95% CI of type 1 diabetes among children aged (0–14) and young adults aged (15–30) by sex and parental country of birth, Sweden, 1969–2009

| Parental immigration Status | Cases | PYRs | IRR* (95% CI) | IRR† (95% CI) | Cases | PYRs | IRR* (95% CI) | IRR† (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (0–14) | Female (0–14) | |||||||

| Mother foreign born | 871 | 3 810 384 | 0.76 (0.71–0.81) | 0.69 (0.64–0.74) | 808 | 3 610 118 | 0.79 (0.73–0.85) | 0.71 (0.66–0.77) |

| Father foreign born | 858 | 3 948 653 | 0.72 (0.67–0.77) | 0.65 (0.61–0.70) | 833 | 3 764 091 | 0.78 (0.73–0.84) | 0.70 (0.65–0.75) |

| Both parents foreign born | 443 | 2 249 700 | 0.66 (0.60–0.73) | 0.58 (0.52–0.64) | 435 | 2 134 846 | 0.73 (0.66–0.80) | 0.62 (0.56–0.69) |

| Both parents born in Sweden | 8334 | 26 670 322 | 1 | 1 | 7417 | 25 249 558 | 1 | 1 |

| Male (15–30) | Female (15–30) | |||||||

| Mother foreign born | 624 | 2 791 560 | 0.82 (0.75–0.89) | 0.79 (0.73–0.86) | 510 | 2 635 294 | 0.82 (0.75–0.90) | 0.85 (0.77–0.93) |

| Father foreign born | 618 | 2 636 310 | 0.86 (0.79–0.93) | 0.83 (0.76–0.90) | 442 | 2 504 279 | 0.75 (0.68–0.82) | 0.79 (0.72–0.87) |

| Both parents foreign born | 270 | 1 287 893 | 0.76 (0.68–0.86) | 0.72 (0.64–0.82) | 204 | 1 215 563 | 0.71 (0.62–0.81) | 0.75 (0.65–0.86) |

| Both parents born in Sweden | 8024 | 29 689 985 | 1 | 1 | 6627 | 28 192 526 | 1 | 1 |

*Adjusted for age in 5 years categories.

†Mutually adjusted for age, parental education and calendar years of follow-up.

IRR, incidence rate ratios; PYRs, person-years.

As compared to young adults (15–30 years) of Swedish-born parents, young adults with only one parent born abroad had about 15–20% lower IRR of type 1 diabetes and among young adults with both parents born abroad, the risks were reduced by 25–30% (table 1).

Next, we investigated risks of type 1 diabetes by parental region of birth. Compared with young offspring (0–30 years) of Swedish-born parents, male and female offspring of mothers or fathers born in Africa had about 20–40% higher IRR of type 1 diabetes (table 2). The increased risk of type 1 diabetes was more prominent among individuals whose mothers or fathers were born in Eastern Africa. With a few exceptions, male and female offspring of mothers or fathers born in Asia, Europe (except Northern Europe), Latin America and Northern America (except female offspring to fathers from Northern America) had between 35% and 65% lower IRR than male and female offspring of Swedish-born parents (table 2). These reductions in risks became even more prominent when we confined the analyses to parents born in the same region (table 2). Offspring of Finnish immigrants and rest of Northern Europe had almost similar risks compared with offspring of Swedes (table 2).

Table 2.

Incidence rate ratio (IRR) and 95% CI of type 1 diabetes among male and female ages 0–30 years by parental country of birth and sex Sweden, 1969–2009

| Parental country of birth | IRR* (95% CI) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male |

Female |

|||||||||||

| Cases | Offspring of mother | Cases | Offspring of father | Cases | Offspring of both parents | Cases | Offspring of mother | Cases | Offspring of father | Cases | Offspring of both parents | |

| Sweden | 16 358 | 1 | 16 358 | 1 | 16 358 | 1 | 14 044 | 1 | 14 044 | 1 | 14 044 | 1 |

| Africa | 92 | 1.42 (1.15 to 1.75) | 148 | 1.19 (1.01 to 1.41) | 78 | 1.12 (0.90 to 1.41) | 86 | 1.33 (1.10 to 1.65) | 129 | 1.33 (1.12 to 1.59) | 75 | 1.32 (1.05 to 1.66) |

| Northern Africa | 21 | 1.18 (0.77 to 1.81) | 55 | 1.06 (0.81 to 1.40) | 16 | 0.86 (0.53 to 1.40) | 26 | 1.27 (0.86 to 1.86) | 50 | 1.18 (0.89 to 1.55) | 19 | 1.25 (0.80 to 1.96) |

| Western Africa | 4 | – | 17 | 0.89 (0.55 to 1.42) | 2 | – | 5 | 0.76 (0.32 to 1.83) | 12 | 0.99 (0.56 to 1.74) | 4 | – |

| Eastern Africa | 66 | 1.51 (1.18 to 1.92) | 70 | 1.46 (1.15 to 1.85) | 58 | 1.45 (1.12 to 1.88) | 51 | 1.47 (1.11 to 1.93) | 62 | 1.61 (1.25 to 2.10) | 47 | 1.44 (1.08 to 1.92) |

| Asia | 133 | 0.37 (0.31 to 0.44) | 155 | 0.40 (0.34 to 0.47) | 107 | 0.36 (0.30 to 0.44) | 137 | 0.48 (0.40 to 0.56) | 155 | 0.49 (0.42 to 0.57) | 108 | 0.45 (0.37 to 0.54) |

| Europe | ||||||||||||

| Finland | 692 | 0.98 (0.91 to 1.10) | 523 | 0.99 (0.90 to 1.08) | 273 | 0.96 (0.85 to 1.08) | 587 | 0.96 (0.89 to 1.05) | 442 | 0.97 (0.88 to 1.06) | 232 | 0.93 (0.82 to 1.06) |

| North Europe (excluding Finland) | 240 | 0.88 (0.77 to 1.00) | 258 | 0.89 (0.78 to 1.00) | 46 | 0.89 (0.67 to 1.19) | 235 | 0.99 (0.87 to 1.12) | 231 | 0.91 (0.80 to 1.04) | 38 | 0.82 (0.60 to 1.13) |

| South, East and West Europe | 284 | 0.55 (0.49 to 0.62) | 319 | 0.53 (0.47 to 0.59) | 110 | 0.39 (0.33 to 0.47) | 227 | 0.53 (0.46 to 0.60) | 264 | 0.52 (0.46 to 0.58) | 95 | 0.41 (0.33 to 0.50) |

| Latin America | 39 | 0.56 (0.41 to 0.77) | 51 | 0.65 (0.49 to 0.87) | 17 | 0.39 (0.24 to 0.63) | 29 | 0.51 (0.35 to 0.75) | 23 | 0.33 (0.21 to 0.51) | 14 | 0.41 (0.24 to 0.69) |

| North America | 13 | 0.50 (0.29 to 0.86) | 20 | 0.55 (0.36 to 0.86) | 0 | – | 15 | 0.78 (0.47 to 1.30) | 31 | 1.02 (0.72 to 1.46) | 0 | – |

| Oceania | 2 | – | 2 | – | 0 | – | 2 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Mixed† | 0 | – | 0 | – | 84 | 0.64 (0.52 to 0.79) | 0 | – | 0 | – | 82 | 0.75 (0.61 to 0.94) |

IRRs significantly different from 1 are bolded.

*Adjusted for age, parental education and calendar-years of follow-up.

†Both parents are not from the same country or region.

The results from the sensitivity analysis, where we repeated the analysis and confined our cohort to individuals born in Sweden between 1997 and 2009 (limited to children ages 0–13), were similar to the results of the entire cohort for the same age category (see online supplementary tables S2A and B).

Discussion

In this nationwide cohort study of Sweden-born children and young adults, we observed a continuing increase of type 1 diabetes in individuals younger than 15 years of age over the past decades. This increase was, however, less evident among offspring of immigrants than in offspring of native Swedes. In contrast, no change in trend was observed among young individuals between 15 and 30 years of age, and regardless of parental country of birth.

An interesting finding in the present study was an almost identical pattern with a shift towards lower age at onset of type 1 diabetes by younger birth cohorts in both offspring of foreign born parents and Swedes.

Over the past decades, a rapid rise in the incidence of type 1 diabetes has been demonstrated.23 24 The finding of an increased incidence rate of type 1 diabetes between 1969 and 2009 among individuals below 15 years of age, and a decreasing or steady incidence rate among young adults, is in line with previous studies from Sweden6 and other parts of the world.7 The observed increasing trend over time in our study might be due to the quality of National patient Register over time and not covering all of Sweden for the entire period of our study. This register became nationwide in 1987. However, the sharpest increase in incidence observed in our study among individuals below 15 years of age is after around 1997 when the inpatient register had full coverage and when the ICD-10 were able to disentangle different types of diabetes.

The finding of an almost identical pattern with a shift towards lower age at the onset of type 1 diabetes in offspring of foreign born parents as well as Swedes indicates the exposure to similar environmental factors in both groups. It has been hypothesised that this development is due to increased exposures in early life to factors that initiate and/or accelerate β-cell destruction, including viral infections, rapid postnatal growth and nutritional factors.25 26 In addition, perinatal factors such as blood-group incompatibility, high maternal age, preeclampsia and caesarean section delivery have been shown to be associated with increased incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes.27 Similar findings of a shift towards younger age at diagnosis and a declining incidence of type 1 diabetes among young adults aged 15–34 years were also observed in other studies from Sweden, using the two nationwide prospectively collected research register, the Swedish Childhood Diabetes Register and the Diabetes Incidence Study in Sweden.10 28 The shift towards younger age at diagnosis may be due to risk factors accelerating the disease process.

We further found that offspring with one or two parents born abroad had a reduced risk of type 1 diabetes compared with offspring to Sweden-born parents. The reduction in risk was similar between sexes and was more apparent among individuals where both parents were foreign born. Stratification by specific parental region/country of birth, however, revealed that this reduction was confined to offspring of immigrants from Asia, Latin and North America, South, West and East Europe. In contrast, the IRR for type 1 diabetes was increased in individuals with African parents, particularly so if the parents were born in Eastern or Northern Africa. The observed increased risk among offspring of Africans in this study, in line with a previous Swedish register study,29 is also observed in Swedish residents born in Africa.8 29 It is unclear if these findings reflect a high risk of type 1 diabetes in the countries of origin, thus rating Eastern and Northern Africa as the areas with the highest incidence of type 1 diabetes in the world. At the same time we should keep in mind that the population of immigrants in Sweden may not represent the population of countries of origin.

The reported low number of type 1 diabetes diagnoses in Africa30 is most likely to be underestimated due to the lack of diagnostic measures,31 and high mortality among uncontrolled type 1 diabetes cases as a result of limited access to insulin treatment.32 Moreover, priorities are mostly given to the high burden of communicable diseases in African countries,33 especially in busy emergency hospitals. As a consequence, children with diabetic ketoacidosis at the time of diagnosis34 could be misdiagnosed as cerebral malaria or meningitis35 which would also lead to an underestimation of type 1 diabetes cases. The observed higher risk in African offspring in the present study and the increased risk of type 1 diabetes in Swedish residents born in Africa8 might be due to genetic propensity interacting with environmental factors in the new home country.

Offspring of Swedish residents born in Asia, Latin and North America, South, West and East Europe retained the low risk profile were recently observed in young immigrants in Sweden born in these areas.8 This risk reduction was independent of maternal or paternal birth region but was stronger if both parents were born in the same region.

The importance of the parental country of birth for the risk of developing type 1 diabetes has also been observed in other studies36–39 and may indicate the role of genetic factors.40 41 Children of Sardinian heritage (a high risk area), born and living in Lazio (a low risk area) retained the high risk profile of Sardinia.42 The risk for type 1 diabetes in children of Yugoslavian, Italian and Greek heritage in Germany was closer to the reported incidence in those countries than in Germany.43 However, the importance of life style or environmental factors interacting with genetic factors cannot be ruled out44 as studies of immigration from regions with low to high incidence of type 1 diabetes have been associated with increased incidence of type 1 diabetes.37

The primary strength of our study is the nationwide cohort design with nearly complete follow-up of type 1 diabetes occurrence over several decades. Using a unique PIN assigned to all Swedish citizens, we were able to correctly assess exposure (parental country of birth) and thus avoid misclassification bias.

We lacked specific ICD codes for type 1 diabetes in the earlier versions of ICD before 1997 (ie, eighth and ninth version of ICD). However, the results of the sensitivity analysis limited to only cases of type 1 diabetes according to ICD-10 for the years 1997 and forward were similar to the results for the entire period of the study. But, in this sensitivity analysis, we were only able to verify the results for children born between 1997 and 2009 (0–13 years old). Whereas, for the age groups over 15 years when type 1 diabetes is more likely to be mixed with type 2 diabetes, we had no data. However, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes is low in Sweden45 46 and other northern European countries, and most likely the majority of cases of diabetes diagnosed before 30 years are true type 1 diabetes. While this may not be applicable for offspring born to parents from other parts of the world with known high prevalence of type 2 diabetes which may have led to overestimation of the true type 1 diabetes.

Our findings of a lower IRR of type 1 diabetes among children and young adults with one or two foreign born parents, with the notable exception of offspring of African immigrants and the shifting of age at diagnosis towards younger age in offspring of Swedes as well as of immigrants highlight the important role of environmental factors and its interaction with genetic background in the aetiology of type 1 diabetes.

In order to further clarify potential pathophysiological mechanisms for the development of type1 diabetes, further studies are needed with data on important exposures such as viral infections in early life, nutritional habits and weight gain in infancy. Moreover, studies on offspring of immigrants from African countries, in particular from Eastern Africa, might improve our understanding on the aetiology of the disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Sven Cnattingius, for his critical review of the manuscript. The authors appreciate the help from Statistics Sweden and the National Board of Health and Welfare, which provided them with data.

Footnotes

Contributors: HIH designed the research, drafted the manuscript, analysed the data and interpreted the results. MP designed the research, interpreted the results critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. TM designed the research, interpreted the results, critically reviewed and edited the manuscript, handled research data and funding, and supervised.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from The Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research-Kurdistan Regional Government/Iraq, and the Department of Environmental Medicine, Karolinska institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Dabelea D. The accelerating epidemic of childhood diabetes. Lancet 2009;373:1999–2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berhan Y, Waernbaum I, Lind T, et al. Thirty years of prospective nationwide incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes: the accelerating increase by time tends to level off in Sweden. Diabetes 2011;60:577–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kondrashova A, Reunanen A, Romanov A, et al. A six-fold gradient in the incidence of type 1 diabetes at the eastern border of Finland. Ann Med 2005;37:67–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pitkaniemi J, Onkamo P, Tuomilehto J, et al. Increasing incidence of type 1 diabetes—role for genes? BMC Genet 2004;5:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hyttinen V, Kaprio J, Kinnunen L, et al. Genetic liability of type 1 diabetes and the onset age among 22,650 young Finnish twin pairs: a nationwide follow-up study. Diabetes 2003;52:1052–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pundziute-Lycka A, Dahlquist G, Nystrom L, et al. The incidence of type I diabetes has not increased but shifted to a younger age at diagnosis in the 0–34 years group in Sweden 1983–1998. Diabetologia 2002;45:783–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weets I, De Leeuw IH, Du Caju MV, et al. The incidence of type 1 diabetes in the age group 0–39 years has not increased in Antwerp (Belgium) between 1989 and 2000: evidence for earlier disease manifestation. Diabetes Care 2002;25:840–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hussen HI, Yang D, Cnattingius S, et al. Type I diabetes among children and young adults: the role of country of birth, socioeconomic position and sex. Pediatr Diabetes 2012;14:138–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karvonen M, Pitkäniemi M, Pitkäniemi J, et al. Sex difference in the incidence of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: an analysis of the recent epidemiological data. World Health Organization DIAMOND Project Group. Diabetes Metab Rev 1997;13:275–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ostman J, Lonnberg G, Arnqvist HJ, et al. Gender differences and temporal variation in the incidence of type 1 diabetes: results of 8012 cases in the nationwide Diabetes Incidence Study in Sweden 1983–2002. J Intern Med 2008;263:386–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beiki O, Stegmayr B, Moradi T. Country reports: Sweden. In: Razum O, Spallek J, Reeske A, et al. eds. Migration-sensative cancer registration in Europe. Lang, 2011:106–23 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ludvigsson JF, Olausson PO, Pettersson BU, et al. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2009;24:659–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johannesson I. The total population register of statistics Sweden. New possibilities and better quality. Statistics Sweden: Örebro, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Socialstyrelsen Causes of death, The National Board of Health and Welfare, CENTRE FOR EPIDEMIOLOGY. Official Statistics of Sweden, 2007

- 15.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011;11:450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kvalitet och innehåll i patientregistret. 2009. (cited 8 May 2010); The National Board of Health and Welfare Socialstyrelsen. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se.

- 17.The Multi-Generation Registry Bakgrundsfakta till befolknings-ochvälfärdsstatistik. Statistska Centralbyrån: Örebro, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Statistics_Sweden. Folk- och bostadsräkningar, FoB. 2010 [cited 25 February 2010]; http://www.scb.se.

- 19.Socialstyrelsen Longitudinal integration database for health insurance and labour market studies (LISA by Swedish acronym). 2010. [cited 10 August 2010]; http://www.socialstyrelsen.se

- 20.Ahmad Omar B.CB-P Lopez AD, Murray CJL, et al. Age standardization of rates: a new who standard. GPE Discussion Paper Series: No. 31, EIP/GPE/EBD, World Health Organization, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Statistical Research and Applications Branch NCI Joinpoint regression program. 2008. Version 3.3.1

- 22.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, et al. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med 2000;19:335–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green A, Patterson CC. Trends in the incidence of childhood-onset diabetes in Europe 1989–1998. Diabetologia 2001;44(Suppl 3):B3–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DIAMOND Project Group Incidence and trends of childhood type 1 diabetes worldwide 1990–1999. Diabetic Med 2006;23:857–86666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dahlquist G. Can we slow the rising incidence of childhood-onset autoimmune diabetes? The overload hypothesis. Diabetologia 2006;49:20–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haynes A, Bower C, Bulsara MK, et al. Perinatal risk factors for childhood type 1 diabetes in Western Australia—a population-based study (1980–2002). Diabet Med 2007;24:564–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dahlquist GG, Patterson C, Soltesz G. Perinatal risk factors for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe. The EURODIAB Substudy 2 Study Group. Diabetes Care 1999;22:1698–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dahlquist GG, Nystrom L, Patterson CC. Incidence of type 1 diabetes in Sweden among individuals aged 0–34 years, 1983–2007: an analysis of time trends. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1754–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hjern A, Soderstrom U, Aman J. East Africans in Sweden have a high risk for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012;35:597–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karvonen M, Viik-Kajander M, Moltchanova E, et al. Incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes worldwide. Diabetes Mondiale (DiaMond) Project Group. Diabetes Care 2000;23:1516–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall V, Thomsen RW, Henriksen O, et al. Diabetes in Sub Saharan Africa 1999–2011: epidemiology and public health implications. A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2011;11:564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.http://www.idf.org/diabetesatlas/5e/africa

- 33.Majaliwa ES, Elusiyan BE, Adesiyun OO, et al. Type 1 diabetes mellitus in the African population: epidemiology and management challenges. Acta Biomed 2008;79:255–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monabeka HG, Mbika-Cardorelle A, Moyen G. [Ketoacidosis in children and teenagers in Congo]. Sante 2003;13:139–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rwiza HT, Swai AB, McLarty DG. Failure to diagnose diabetic ketoacidosis in Tanzania. Diabet Med 1986;3:181–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hjern A, Soderstrom U. Parental country of birth is a major determinant of childhood type 1 diabetes in Sweden. Pediatr Diabetes 2008;9:35–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cataldo F. Early onset of type 1 diabetes mellitus in immigrant children from developing countries to Western Europe: the role of environmental factors? J Endocrinol Invest 2005;28:574–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soderstrom U, Aman J, Hjern A. Being born in Sweden increases the risk for type 1 diabetes—a study of migration of children to Sweden as a natural experiment. Acta Paediatr 2012;101:73–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Podar T, Laporte RE, Tuomilehto J, et al. Risk of childhood type 1 diabetes for Russians in Estonia and Siberia. Int J Epidemiol 1993;22:262–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patrick SL, Kadohiro JK, Waxman SH, et al. IDDM incidence in a multiracial population. The Hawaii IDDM Registry, 1980–1990. Diabetes Care 1997;20:983–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ji J, Hemminki K, Sundquist J, et al. Ethnic differences in incidence of type 1 diabetes among second-generation immigrants and adoptees from abroad. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:847–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muntoni S, Fonte MT, Stoduto S, et al. Incidence of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus among Sardinian-heritage children born in Lazio region, Italy. Lancet 1997;349:160–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neu A, Willasch A, Ehehalt S, et al. Diabetes incidence in children of different nationalities: an epidemiological approach to the pathogenesis of diabetes. Diabetologia 2001;44(Suppl 3):B21–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zung A, Elizur M, Weintrob N, et al. Type 1 diabetes in Jewish Ethiopian immigrants in Israel: HLA class II immunogenetics and contribution of new environment. Hum Immunol 2004;65:1463–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arnqvist HJ, Littorin B, Schersten B, et al. Difficulties in classifying diabetes at presentation in the young adult. Diabet Med 1993;10:606–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lynch KF, Subramanian SV, Ohlsson H, et al. Context and disease when disease risk is low: the case of type 1 diabetes in Sweden. J Epidemiol Community Health 2010;64:789–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.