Abstract

Single photons are of paramount importance to future quantum technologies, including quantum communication and computation. Nonlinear photonic devices using parametric processes offer a straightforward route to generating photons, however additional nonlinear processes may come into play and interfere with these sources. Here we analyse spontaneous four-wave mixing (SFWM) sources in the presence of multi-photon processes. We conduct experiments in silicon and gallium indium phosphide photonic crystal waveguides which display inherently different nonlinear absorption processes, namely two-photon (TPA) and three-photon absorption (ThPA), respectively. We develop a novel model capturing these diverse effects which is in excellent quantitative agreement with measurements of brightness, coincidence-to-accidental ratio (CAR) and second-order correlation function g(2)(0), showing that TPA imposes an intrinsic limit on heralded single photon sources. We build on these observations to devise a new metric, the quantum utility (QMU), enabling further optimisation of single photon sources.

Photons are a key building block for future quantum technologies and are the most suitable choice for linking distant quantum systems1. Deterministic single photon sources based on quantum dots2 and defects in diamond3 are being heavily investigated, however they are currently limited due to the inherent randomness of emission direction, large bulk optical collection setups and most often the use of cryogenic temperatures, all of which make this technology challenging to scale up. The generation of photons through probabilistic processes in bulk nonlinear materials has been a workhorse for quantum information experiments4,5,6,7,8. In recent years, integrated waveguide devices have emerged as an attractive platform for scalable quantum technologies7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. These chip-scale platforms are typically made of glasses, such as silica and chalcogenide, or semiconductors such as silicon (Si) and gallium indium phosphide (GaInP). In contrast to earlier free-space investigations, one must consider additional effects induced by the media and their role in the generation and collection of photons. In amorphous materials, spontaneous Raman scattered photons act as a noise source, dramatically impacting the desired quantum statistics10,19,20. In crystalline semiconductor materials multi-photon absorption and accompanying free carrier effects are present at larger intensities. While the roles of multi-photon effects in the classical regime are reasonably well known21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29, quantum pair generation processes in these materials have only recently been investigated11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. Though these initial observations noted that nonlinear absorption affected the experiments, at present the nuanced roles of the multi-photon processes in the quantum regime is unclear.

In this paper we analyse the interaction of probabilistic photon generation with multi-photon processes in both the generation and collection of single photons for the first time. We carry out experiments in Si16,17 and GaInP18 semiconductor waveguides which display inherently different nonlinear absorption processes, namely two-photon (TPA) and three-photon absorption (ThPA), respectively. We develop a novel model capturing these effects, including slow-light enhancements in the photonic crystal periodic media16,17,18,21,22,23,24,25,26. The series of measurements of brightness, coincidence-to-accidental ratio (CAR) and second-order correlation function g(2)(0) are in excellent quantitative agreement with our theoretical model, demonstrating this framework is suitable for predicting photon generation in the presence of strong nonlinear effects. We show that TPA imposes an intrinsic limit on heralded single photon generation even in the single photon pair regime. We finally devise a new metric, the quantum utility or QMU, that unites several key parameters of single photon devices and show an example of its use to improve our current devices. This metric should facilitate the development of optimised multiplexed and integrated photon sources, thereby opening new routes to scalable quantum computation and simulation with large numbers of photonic qubits.

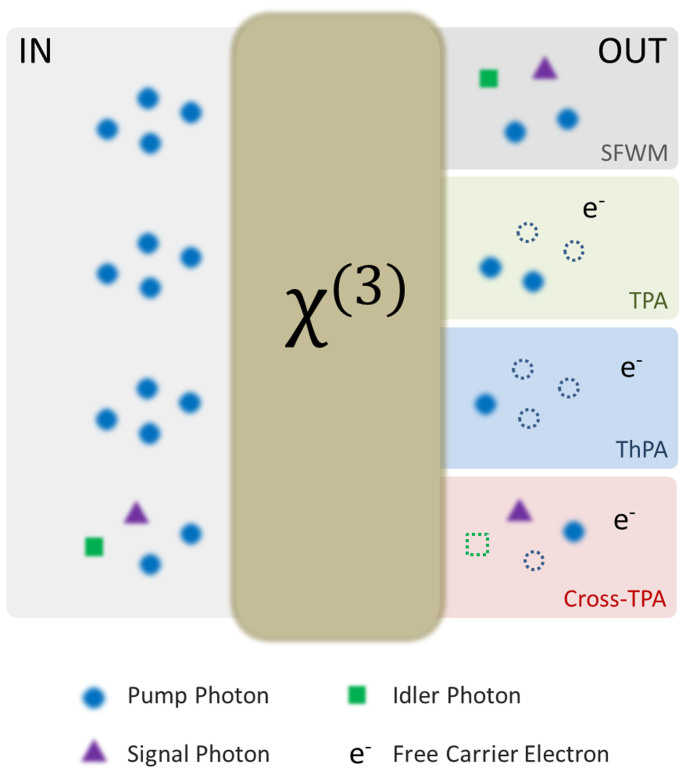

Figure 1 illustrates the various nonlinear processes considered. Photons from a pulsed laser are injected to the third-order χ(3) nonlinear device, where a number of processes can occur. The primary process for the generation of photons is spontaneous four-wave mixing (SFWM) where two pump photons are annihilated to generate entangled signal and idler photons at higher and lower energy, respectively. The nonlinear absorption processes include TPA, the markedly weaker ThPA, and any related free carrier absorption (FCA) induced by electrons generated from these processes. We include these losses to the pump photons propagating through the nonlinear medium, as well as through cross-TPA (XTPA) between a pump photon and a signal or idler photon. Though XTPA between the generated signal and idler photons is also possible, this is a weak effect due to the small intensities of single photons and is neglected here. In the experiments we found ThPA and cross-ThPA play negligible roles in the quantum regime. Consequently, we focus the discussion on TPA, XTPA, and FCA.

Figure 1. Schematic of third-order χ(3) nonlinear processes.

Pump photons are input to the nonlinear material (brown). A number of processes can occur in the system including: the primary photon-pair generation process of SFWM and the secondary nonlinear processes causing loss to the pump such as TPA and ThPA, and processes causing loss of generated photons, cross-TPA (XTPA).

Results

Heralded single photon generation with multi-photon absorption

The novelty of our approach is the incorporation of nonlinear absorption processes in four major aspects of SFWM photon pair generation and collection. The generation terms are described by the interaction of multi-photon absorption with the strong pump beam. In this regard, TPA impacts both (i) the nonlinear phase shift Φ (radians), as well as (ii) the phase matching of the parametric process. Once generated, multi-photon absorption also affects (iii) the absorption of the signal or idler single photons with the co-propagating pump beam via XTPA and (iv) absorption of single photons by free-carriers generated by the pump (FCA).

First, we consider the impact of TPA on the probability of generating a pair of photons per laser pulse, μ. In the case of SFWM, this probability scales as μ ~ Φ2Θ2 with the nonlinear phase shift Φ and phase matching terms Θ (see Supplementary Information). In the presence of TPA, Φ scales logarithmically with power28

|

where γ = kon2/Aeff is the nonlinear parameter, Kerr coefficient n2, effective area Aeff, wave number k0, α2 the TPA coefficient, I0 = Po/Aeff the pump intensity with peak power P0, Leff = 1 − exp(−αL)/(α) the effective device length with scattering loss α, and S = (ng/n0) the slow-down factor in the photonic crystal waveguide (PhCW)22,24,30. Similar scaling occurs for coupled-cavity waveguides15,31. In the experiments we control Φ by varying the input laser power. While earlier work suggests the role of TPA in reducing coincidence counts in the SFWM process11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18, here we describe the various roles of nonlinear absorption and quantitatively include these effects in our photon pair model. While this description of Φ is pertinent to Si, we note that a linear definition of Φ = γS2P0Leff is appropriate for GaInP at the power levels used in these experiments. Second, as SFWM is a parametric process one must also consider the phase matching conditions. In particular, Θ is a function of Φ (see Supplementary Information).

Further to these two mechanisms where TPA influences the pump during pair generation, multi-photon absorption also strongly affects the generated single photons by introducing two loss channels in the collection. The third impact of multi-photon absorption is a collection loss due to absorption of single photons through XTPA of the signal or idler single photons with the co-propagating pump beam. For two co-polarised beams, this effect is described by

|

where ηXTPA ≤ 1 is the collection efficiency per photon. The fourth impact of multi-photon absorption is the generation of free carriers during pump propagation via TPA. FCA of single photons is described by

|

where σ is the absorption cross section, Nc is the carrier density and Leff(2α) = 1 − exp(−2αL)/(2α)21,28. Equivalent expressions exist for ThPA, though we exclude these here due to the fact that they are negligible at intensity values required for heralded single photons from SFWM. This is the first time the role of multiphoton absorption, in particular TPA, XTPA, and FCA, have been quantitatively analysed in photon pair generation and collection. We note equivalent expressions could be derived for microcavities, where the nonlinear enhancement arises from the ratio of quality factor (Q) to mode volume (V)32, and other slow-light structures such as coupled-resonator optical waveguides (CROW)15,33. Single photon sources based on down-conversion in χ(2) media such as AlGaAs waveguides would also have to consider these effects34,35. Notably, experimental evidence indicates the material α2 parameter in down conversion experiments can be much larger than the present case due to the extreme non-degeneracy of the photons29 in contrast to our nearly degenerate case.

Experiments and modeling of SFWM pair generation in photonic crystal waveguides: linear and TPA regimes

We performed a number of experiments on photonic crystal waveguides fabricated in two different nonlinear semiconductor materials, namely Si and GaInP, to examine the heralded photon generation in the presence of nonlinear absorption and compare them to theoretical predictions (see Methods section for device and experimental details). At large intensities these materials exhibit two and three-photon absorption, respectively, for the photon energies (0.8 eV) in our experiments.

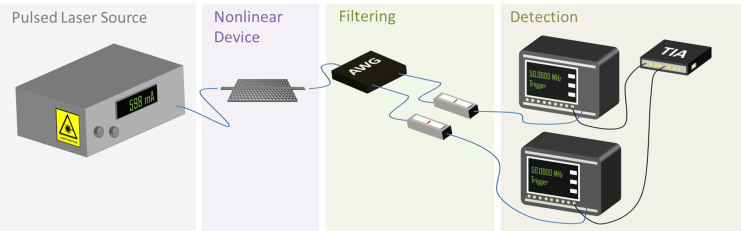

To confirm these observations we create a model for the generation, filtering and detection system, shown in Fig. 2, which we treat in a similar way to Bussières et al.36. For the generation term, we define pi as a thermal distribution dependent on μ, the number of pairs per pulse (including our TPA and slow-light modifications). This distribution is appropriate when the filtering matches the pump pulse bandwidth37. For the photon pair collection, we create a vector describing the state of the detector system indicating the probability of each detector switching from the unclicked state to the clicked state (see Methods and Supplementary Information). We construct accompanying matrices describing the (i) detector dark counts MD and (ii) loss mechanisms of generated photons in the system Mη (see Methods section). The Mη matrix describes the photon collection efficiencies  , as well as intrinsic losses of single photons due to propagation ηα = exp(−αL) and our newly derived nonlinear loss terms ηNL = ηXTPAηFCA

, as well as intrinsic losses of single photons due to propagation ηα = exp(−αL) and our newly derived nonlinear loss terms ηNL = ηXTPAηFCA

|

where the subscripts S, I correspond to the signal and idler channels, respectively. These matrices act on an original vector set to an initial unclicked state and are populated with a thermal distribution of photons related to μ. We account for the probability of generating multiple pairs per pulse in the SFWM process through terms proportional to μn, where n is the number of generated photon pairs. The final output vector provides the total probability for all detector states and coincidence terms.

Figure 2. Schematic of the experimental system under consideration.

A fiber laser generates 10 ps pulses in the telecommunications band at a repetition rate of 50 MHz which are injected into the photonic crystal waveguide (PhCW) under test using lensed fibers. Photons are generated through SFWM, separated using an arrayed waveguide grating (AWG) and filtered using tunable bandpass filters. The generated photons are then detected using single photon detector modules triggered in synchrony with the laser source and coincidence events are measured using a time interval analyser (TIA). Figure 2 was drawn by Alex Clark.

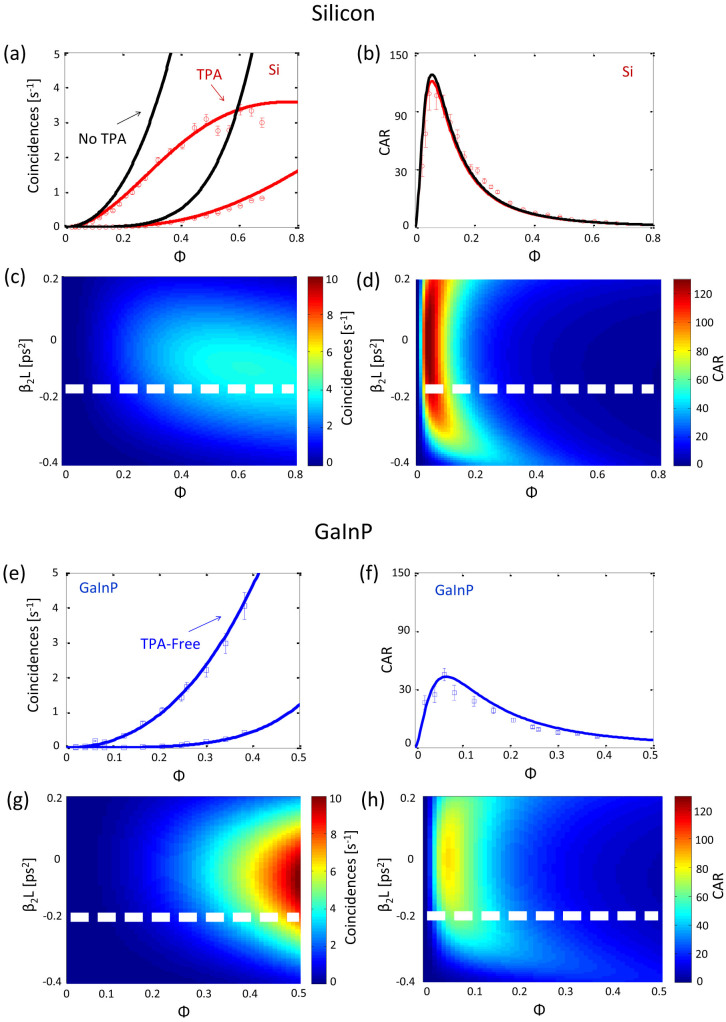

Figure 3(a) shows the experimentally measured coincidence counts versus Φ for Si (at a group-velocity dispersion (GVD) of β2. β2 = −0.9 ps2/mm). The modelled results are in excellent agreement with the experimental data points in terms of both the SFWM photon coincidence counts (upper curves) and the accidental coincidence counts arising from detector dark counts, multi-pair emission and any residual leaked pump (lower curves). The black lines are theoretical curves with numerically suppressed TPA (and therefore FCA) showing a significant increase in both coincidences and accidentals. Of particular interest is the flattening to a maximum count of less than five-per-second for the Si device due to both the restricted Φ in the generation, as well as XTPA and FCA of the generated pairs in the collection.

Figure 3. Evolution of coincidence counts and CAR plots with respect to nonlinear phase shift, Φ.

(a)–(d) Plots related to Si. (a) Experimental coincidence and accidental coincidence count data (circles) along with the model (solid red lines) for Si. Modelling with numerically suppressed TPA (black line) is also indicated. (b) Experimental CAR versus Φ for Si. Solid red lines are the full model while the (black lines) indicated numerically suppressed TPA. (c) Contour plots of coincidence counts and (d) CAR with respect to Φ as the GVD is varied for silicon with fixed experimental lengths. The experimental β2L is marked by the white dashed line. (e)–(h) Plots related to GaInP. The experimental data (squares) and model (lines) are as in (a)–(d). GaInP shows a quadratic increase in coincidence counts due to the lack of nonlinear absorption in GaInP in the photon pair regime. There is no black curve since there is no TPA in this case. All errors are calculated from Poissonian statistics.

Using the coincidence count data, we calculate the coincidence-to-accidental ratio (CAR), a metric analogous to a signal-to-noise ratio in a classical system. Fig. 3(b) shows the experimental data along with the modelled values once again demonstrating excellent agreement. The black curve in Fig. 3(b) shows a numerical suppression of TPA only slightly reducing the maximum CAR value, despite the strongly suppressed coincidence counts seen in Fig. 3(a). Comparing the strongly modulated coincidence counts in Fig. 3(a) with the relatively unaffected CAR in Fig. 3(b), it is clear that one must look beyond CAR as a simple metric for probabilistic photon sources.

We calculated the coincidence counts and CAR as a function of both group velocity dispersion (GVD) and Φ, including slow-light effects in the PhCW21,22,24. Figures 3(c) and (d) show numerically computed contour plots of the coincidence counts and car for Si. The experimental device GVD-length product is indicated by the dashed white line through the plot (β2L = −0.18 ps2). The experimental wavelength is determined by the frequency spacing of our arrayed waveguide grating (AWG) filter. We observe in Figs. 3(c) and (d) that both GVD and Φ determine the best operating point, a fact that must be taken into consideration when designing and fabricating photon pair sources based on SFWM. The tilt of the coincidence contours towards anomalous (negative) GVD is required to balance the nonlinear (positive) contribution to the phase matching. We note the nonlinear contribution dominates in these chip-scale devices in contrast to the linear dispersion contribution that is more significant for fibre-based sources20,38,39,40. In the case of Si, TPA additionally saturates Φ, as noted previously, causing an adjustment to the nonlinear phase matching contribution for photon-pair generation.

We next performed identical measurements in a GaInP PhCW, a material free from TPA in the telecommunications band (Eg = 1.9 eV)21,23,26. Figure 3(e) shows the experimentally measured coincidence counts versus Φ for GaInP (β2 = −0.13 ps2/mm). Note the x-scale (Φ) is smaller for ease of comparison to the coincidence counts (y-scale) with the Si case. In contrast to the roll-off in the TPA-limited material, GaInP exhibits no deviation from the expected quadratic photon pair coincidence rate. Importantly, the ThPA intensity threshold is not reached at the power levels required to generate photon pairs. Essentially GaInP behaves as a linear material in the regimes of interest. Figure 3(f) indicates the measured CAR for the GaInP experiments. The maximum CAR for this device is smaller than Si due to increased linear propagation loss in the longer device of 1.5 mm versus the 0.2 mm for Si. Contour plots of the coincidences and CAR are shown in Fig. 3(g) and (h) for GaInP, with white dashed lines once again indicating the experimental GVD-length product (β2L = −0.20 ps2). Notice that despite very different behaviour in coincidence counts, the CAR plots for Si - Fig. 3(d) and GaInP - Fig. 3(h) behave comparatively at large Φ due to multi-pair generation.

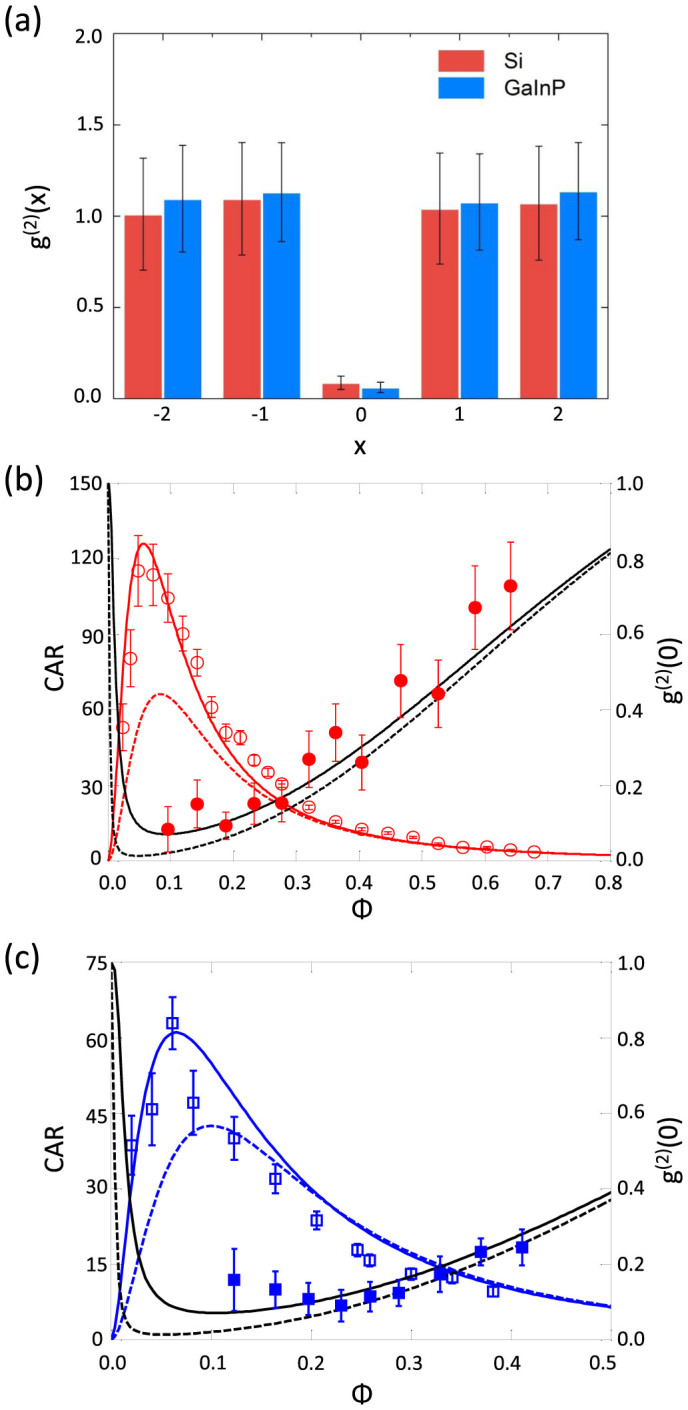

Second-order correlation function measurements

The second-order correlation function, or g(2)(0) is another important metric for single photon sources. The g(2)(0) is an indicator of how well the source output compares to a single photon18,36,41. A g(2)(0) of 0 corresponds to an ideal single photon source while a standard coherent Poissonian light source exhibits a g(2)(0) value of 1. For our three-detector heralded measurement this is described by

|

where Πj|H are the conditional probabilities that the jth detector is triggered when the herald detector H is also triggered (see Supplementary Information). We desire large ΠA|H or ΠB|H which indicate true single photon pairs while simultaneously minimizing ΠAB|H (triples - multiple photons)36,41. To measure this quantity one detects a first photon (the signal) heralding the arrival of a second photon (the idler) with this latter photon passing through a 50:50 coupler and sent to one of two detectors. True single photons will only trigger one of these two detectors. If there is a coincident count across these two detectors the g(2)(0) rises above the ideal value of zero indicating more than a single photon is present.

Figure 4(a) shows our g(2)(x) measurements for the two platforms, where x corresponds to the integer number of delayed pulse periods of one of the heralded photons with respect to the other. True heralded single photon operation only occurs in the g(2)(0) window, achieving minimum g(2)(0) values of 0.09 for Si and 0.06 for GaInP. When x is non-zero, the heralding of the output photon is lost, and the statistics revert to a coherent Poissonian source with g(2)(x) values of 1, as expected.

Figure 4. Second-order correlation function measurement results.

(a) Both Si and GaInP show clear non-classical results at zero delay with values of 0.09 and 0.06 respectively, recovering classical Poissonian statistics at alternative delays. (b)–(c) We plot the experimental and modelled g(2)(0) (solid symbols and black lines) in parallel with the CAR (empty symbols and red and blue lines) for Si (b) and GaInP (c) versus Φ. Dotted lines are numerical extrapolations for the g(2)(0) at the same detector settings as the CAR measurement (black dashed) and the CAR at the same detector settings as the g(2)(0) measurements (blue and red dashed).

The evolution of the g(2)(0) parameter as a function of Φ is shown in Figs. 4(b) and (c) for Si and GaInP, respectively. To model g(2)(0), we extend our previous two-photon formulation to accommodate three detectors. The chief sources increasing g(2)(0) include dark counts at small Φ and multi-pair generation at larger Φ. In both cases the extended g(2)(0) model is once again in solid agreement with the experimental data. The minimum of the g(2)(0) function corresponds to the onset of the multiple pairs-per-pulse (i > 1) (see Supplementary Information).

The present limit to these values is detector dark counts, not the devices themselves. In particular, for the g(2)(0) experiments, we required a larger detection efficiency of ηD = 10% (compared to 7.5% for the CAR experiments) in order to obtain significant counting statistics for the three-photon g(2)(0) measurements. A unique aspect of our model is the ability to numerically extract the g(2)(0) value from our low dark count experimental CAR data. The black dashed lines in Figs. 4(b) and (c) show the extrapolated results reveal a striking g(2)(0) of 0.013 for GaInP and less than 0.007 in the case of Si, a near order of magnitude improvement over our prior record for PhCW devices18. We expect near ideal single-photon operation, g(2)(0) → 0, in our devices with ultra-low dark count detectors such as superconducting detectors42,43. The GaInP is slightly higher due to higher propagation loss in the longer device.

Conversely, we extrapolate a CAR from our experimental g(2)(0), shown as the red/blue dashed lines in Figs. 4(b) and (c). We observe the numerically extrapolated CAR is below the level achieved in the experimental CAR measurements, as expected from the higher dark count rate at ηD = 10%. An interesting feature of the overlaid g(2)(0) and CAR plots is the noticeable correspondence between the minima in the g(2)(0) and the maximum of the CAR. This feature is due to multi-pair generation at large Φ acting as the dominant noise source in these metrics. The g(2)(0) rises above a value of 0.5 for larger Φ as expected (see Supplementary Information).

Implications of TPA and XTPA on heralded single photons

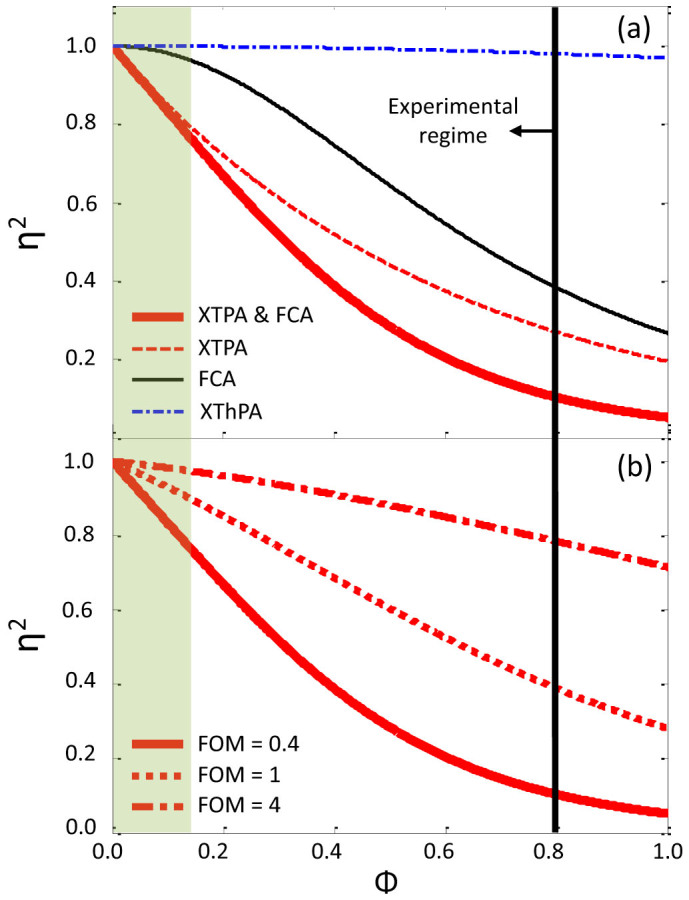

We now look more closely into the role of the multiphoton losses in heralded single photon sources and derive some general conclusions about TPA-limited processes. We describe the photon generation, which affects the pump beam phase shift Φ through TPA and the free carrier population Nc, detailed in the Supplementary Information. Here we focus on XTPA in the collection of single photons and coincidence counts as it has a more pronounced impact than TPA on pair generation. Recall the collection losses given by Eqn. 4 are per photon channel and thus coincidence counts are proportional to the intrinsic collection losses as:  . Figure 5(a) shows the various collection efficiencies squared (proportional to coincidences) versus Φ. We indicate the experimental region in the plot (Φ < 0.8 radians - black line), as well as the single photon pair regime shown as the shaded area. The single photon pair region was determined by setting i = 1 in the model and is consistent for both Si and GaInP. Immediately one notices XTPA is the dominant source of loss in the system, quickly decreasing from 100% even in the single photon pair regime.

. Figure 5(a) shows the various collection efficiencies squared (proportional to coincidences) versus Φ. We indicate the experimental region in the plot (Φ < 0.8 radians - black line), as well as the single photon pair regime shown as the shaded area. The single photon pair region was determined by setting i = 1 in the model and is consistent for both Si and GaInP. Immediately one notices XTPA is the dominant source of loss in the system, quickly decreasing from 100% even in the single photon pair regime.

Figure 5. Role of nonlinear loss processes.

(a) Plot of the collection efficiencies squared (proportional to coincidences) for XTPA, FCA, XThPA versus Φ. It is clear that XTPA reduces the single photon count even in the single photon regime (shaded green). (b) Plot demonstrating an improved nonlinear figure-of-merit (reduced TPA) improves the photon collection efficiency. Nonetheless, photons are always lost when XTPA is present.

The implications of this result are important for single photon sources exhibiting TPA. In particular, heralded single photon sources based on TPA-limited materials will require additional multiplexing, and therefore waveguides and footprint, to achieve the same efficiency compared to linear materials44,45. FCA also sets in and further reduces coincidence counts in the single pair regime and plays a larger role with increasing Φ. Even at the maximum Φ, the estimated contributions of XThPA is <0.2 dB, nearly an order of magnitude smaller than XTPA and FCA-induced pair loss at the same Φ.

Finally, we consider materials with improved nonlinear figures of merit FOMNL = n2/(α2λ) to discern whether TPA is truly an ultimate limit to photon pair generation. Fig. 5(b) shows η2 for various values of FOMNL. Silicon (FOMNL = 0.4) is indicated as the solid line, with hypothetical values of four-fold FOMNL = 1 and ten-fold FOMNL = 4 lower α2 values suggesting drastic improvements. Though XTPA would be diminished in these materials, as η < 1, it is an impairment one must always consider when present. In addition to our experimental demonstrations in GaInP in this work21,23,26, other wide bandgap materials such as AlGaAs27,46 and SiN47,48 are promising candidates for future single photon experiments. The advantages of a TPA-free material, even at the single photon level, will certainly be required for efficient photon generation.

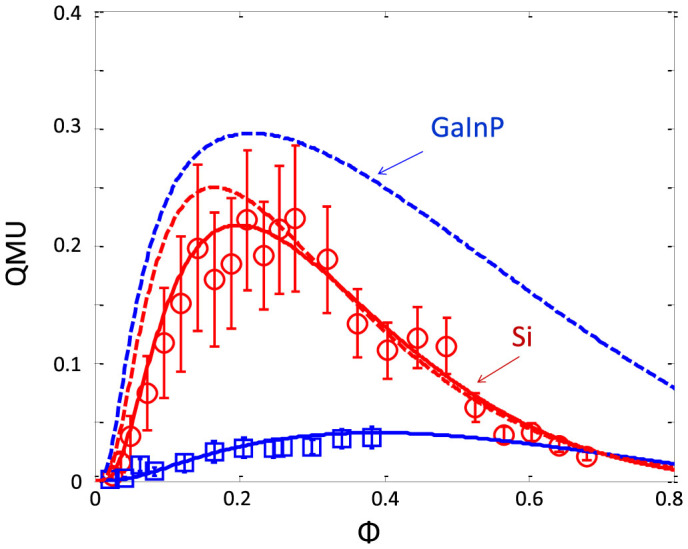

Optimisation of photon sources: the quantum utility

It is clear from this study that developing the ideal photon source requires the optimisation of the output statistics across a number of metrics. For probabilistic photon sources, these include the achievable coincidence count rate, CAR and g(2)(0), which are difficult to optimise simultaneously in a practical environment. While CAR and g(2)(0) are well established measures of probabilistic photon sources, at present no single parameter encapsulates the performance of these devices. With this in mind we have developed a new metric for single photon sources which we term the quantum utility, or QMU, defined as

|

where μ′ is the single photon collection efficiency after any intrinsic device losses.

For a single probabilistic source, μ′ = μη2, with η2 due to propagation and nonlinear losses as defined above, and g(2)(0) is a heralded g(2)(0) measurement. Note that the QMU is a positive value. In the absence of dark counts and noise photons, CAR scales as 1/μ, thereby making the QMU reach a value of one for a single ideal probabilistic photon source. Under these conditions, the CAR and g(2)(0) would yield identical values, even with TPA. The experimental results, however, clearly indicate TPA, XTPA, and FCA reduce the number of coincidence counts as shown in Fig. 3, highlighting the importance of μ′ as an indicator of useful photon pairs. Note that μ′ excludes detector dark counts and any extrinsic losses. Moreover, this metric can be employed for systems without nonlinear loss by setting ηNL = 1 or slow-light by setting S = 1. Importantly, once the measurements are verified with a model, one can remove system-specific effects such as collection or detector efficiencies and dark counts to extract an intrinsic CAR or g(2)(0). Figure 6 shows the experimental points and modelled (solid line) values for the QMU of our devices. We see that the fabricated Si PhCW has a larger maximum QMU of ~0.22. We note that few other papers measure these three quantities in the same experimental setup, and it is consequently difficult to derive a QMU from the literature at present.

Figure 6. Quantum utility (QMU) comparison and extrapolation.

Solid lines represent the modelled quantum utility for the experimental devices, in agreement with data for both Si (red line and circles) and GaInP (blue line and squares). The dispersion values are β2 = −0.9 ps2/mm for Si and β2 = −0.13 ps2/mm for GaInP. Dotted lines represent a numerical fair comparison for Si and GaInP devices of similar length and effective nonlinearity operating at a more favourable dispersion (β2 = −0.1 ps2/mm). The nonlinear losses reduce the QMU for Si.

Building on our observations, we use the model to make a fair comparison of the Si and GaInP devices by assuming devices of the same length of 200 μm, same effective nonlinearities γ, matched group index ng = 37 and coupling loss, all of which are experimentally achievable. We also consider operation at a more favourable phase matching condition than in our experiments by numerically setting the dispersion to β2 = −0.1 ps2/mm (β2L = −0.02 ps2). Figure 6 indicates the numerically extrapolated QMU under these more favourable conditions shown as dashed lines. GaInP reaches a larger maximum QMU of 0.3 compared to the maximum of Si, which reaches a value of 0.25. In addition, the GaInP QMU is higher than Si for all values of the nonlinear phase shift Φ. This implies that GaInP will emit a greater number of coincident photons at a given CAR and g(2)(0) over all coupled powers as compared to silicon. Separate plots of the individual μ′, CAR, and g(2)(0) curves for the comparison case are in the Supplementary Information. At the maximum QMU for GaInP we expect a 5-fold increase in the coincidence counts whilst maintaining a CAR of 30, meaning a four-photon experiment such as quantum interference or an integrated quantum gate could be carried out in a matter of hours rather than days. With the QMU parameter we now have a succinct metric to compare and optimise single-photon sources.

We close with commentary on the broader applicability of the QMU to various single photon sources. As we noted earlier, microcavity32,49, χ(2) waveguide devices34,35 would need to also consider appropriate definitions of the generation term μ′ and the nonlinear loss term ηXTPA. It is also possible to multiplex these single spontaneous heralded sources to create a pseudo-deterministic single photon source44,45. Single photon heralded sources composed of multiplexed probabilistic sources is an area of active research with integrated spatial multiplexing only demonstrated this year50 while temporal multiplexing currently remains undemonstrated51. For a multiplexed heralded source, where the multipair noise is decoupled from the heralded photon rate, a QMU > 1 is possible and is indeed desirable. Concretely, one can operate at the same CAR across a series of multiplexed sources whilst increasing the single photon rate μ′, thereby exceeding the multipair limit of a single probabilistic source.

Discussion

We have described the interaction of probabilistic photon generation with multi-photon processes in both the generation and collection of single photons for the first time. We measured the CAR and g(2)(0) of photon pairs generated from spontaneous four-wave mixing in two representative materials exhibiting two-photon absorption (Si) and three-photon absorption (GaInP), respectively. We developed a model to describe photon-pair generation in highly nonlinear semiconductors incorporating these multi-photon absorption effects and associated free-carriers. The model accurately predicts output photon statistics including source brightness, coincidence-to-accidental ratio and second-order correlation function for heralded photons. Using this model, we showed that TPA imposes an intrinsic limit on heralded single photon generation even in the single photon pair regime for different nonlinear figures of merit. Finally, we formulated a new parameter based on these simple metrics which allows us to optimise photon source parameters for future quantum information science experiments and technology. The development of these sources will be integral to increasing the complexity of quantum photonic experiments.

Methods

Basic formulation of the model

For a two-photon measurement system, such as that used to measure coincidence counts and CAR, we begin by constructing a vector which describes the joint state of the two detectors  , for the signal and idler detectors S and I, where the bar corresponds to no detection. We initialise this vector in the unclicked state such that P0 = (1, 0, 0, 0) and then act upon this with matrices describing the detector dark counts, MD, and system losses, Mη, which have size 2n × 2n, where n is the number of detectors for a number of photon pairs generated, i, such that

, for the signal and idler detectors S and I, where the bar corresponds to no detection. We initialise this vector in the unclicked state such that P0 = (1, 0, 0, 0) and then act upon this with matrices describing the detector dark counts, MD, and system losses, Mη, which have size 2n × 2n, where n is the number of detectors for a number of photon pairs generated, i, such that

|

The probability distribution of photons pi depends on the number of pairs generated per pulse, μ, from a thermal source such that

|

with the nonlinear absorption affecting μ as noted in the main text. Nonlinear losses ηXTPA, ηFCA are included as extra terms in Mη, however could equally be included as separate matrices. By analysing the output vector P on a per pulse basis we are able to extract the coincidences and singles counts, allowing a full calculation of the other metrics for analysing photon sources including the CAR. This method can be extended to three detectors for g(2)(0) correlation function calculations, as described in the Supplementary Information.

Device specifications

The silicon PhCW device is fabricated from a silicon on insulator wafer with a 220 nm silicon membrane layer on 2 μm of silica using electron beam lithography and reactive ion etching. Further fabrication details are available in Ref. (22). The PhCW is made by creating a triangular lattice of holes (lattice parameter of a = 404 nm) with a row missing in the Γ − K direction with the silicon membrane suspended in air. The waveguide is 196 μm long with inverse tapers for improved coupling and polymer waveguides for mode matching to the lensed fibres. The two rows of holes (r = 0.285 a) adjacent to the waveguide are laterally shifted 50 nm outwards to engineer the dispersion52 such that the group index is 30 and is flat to within 10% across the SFWM bandwidth used and centred at a wavelength of 1540.6 nm. The effective nonlinearity γeff = γS2 = 5500 W−1m−1 includes the slow light effect with a linear propagation loss of 65 dB.cm−1, and α2 = 1 cm.GW−1 as determined by prior measurements22,53. The dispersion was measured by Fourier transform spectral interferometry54.

The GaInP device is a 1.5 mm long self-standing membrane of 190 nm thickness with a lattice period a = 470 nm and radius r = 0.22 a. We incorporate inverse tapers to allow efficient mode conversion. Dispersion engineering is achieved through shifting the rows adjacent to the waveguide in opposite directions along the waveguide55, achieving a group index of 20 in the slow light region with the pump centred at 1542.5 nm. The input facet of the GaInP was damaged and limited the amount of achievable phase shift. Coupling is estimated as 9.5 dB in/2.5 dB out. The effective nonlinearity in this device is γeff of 2300 W−1m−1, slightly lower than the silicon device, as extracted in our earlier work30,55,56 with a measured linear propagation loss of 30 dB.cm−1 and dispersion determined by optical frequency domain interferometry57.

Experimental setup

A wavelength tunable C-Band fibre laser provides 10 ps pulses at a repetition rate of 50 MHz which are passed through an isolator to protect the laser. Any residual pump cavity photons are removed by a WDM and any spontaneous Raman scattered photons from the silica fibers are removed with a tunable band-pass filter. The input power is monitored using a power meter. The input pulses are optimised for TE polarization using a polarization controller and coupled to the PhCW under test using 2 μm spot size lensed fibres. Signal and idler photons generated in the PhCW through SFWM are then separated using an arrayed waveguide grating which provides 40 dB of isolation from the pump. Further pump rejection is provided by tunable band-pass filters. We select AWG channels 600 GHz from the pump channel. The photons are then detected using InGaAs avalanche photodiode detectors (ID Quantique ID210) synchronized to the laser repetition rate and set to a detection efficiency of 7.5% resulting in dark counts of 1 × 10−6 and 2 × 10−6 per detection gate in the signal and idler detectors respectively. Coincidence counts are measured using a time interval analyser (TIA). For the g(2)(x) correlation function measurements a 50:50 fiber coupler is added to the idler arm with the outputs connected directly to two InGaAs APDs (ID Quantique ID201) with efficiencies of 10% and dark count levels of 5 × 10−4 per detection gate. The efficiency of the detector in the heralding signal photon arm is increased to 10% to increase the 3-fold coincidence rate and reduce measurement errors. This results in a marked increase to the dark counts in the heralding detector to 4 × 10−6 per detection gate.

Author Contributions

A.C., C.H. and M.C. performed the measurements on the setup developed by M.C., C.X. and A.C. C.H. and A.C. performed the data analysis and modeling. C.H. derived the nonlinear analytic expressions and numerical simulations. S.C., G.L., and I.R. prepared the samples and nanofabrication. B.E., A.D.R., and T.K. supervised the project. C.H. and A.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors confirm the advances described in the paper.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alex Judge for discussions on the CAR model as well as Luke Helt and Mike Steel for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported in part by the Centre of Excellence (CUDOS, project number CE110001018), Laureate Fellowship (FL120100029) and Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE120102069, DE130101148, and DE120100226) programs of the Australian Research Council (ARC), EPSRC UK Silicon Photonics (Grant reference EP/F001428/1), EU FP7 GOSPEL project (grant no. 219299), and EU FP7 COPERNICUS (grant no. 249012).

References

- Gisin N. & Thew R. Quantum communication. Nat. Phot. 1, 165–171 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Ekimov A. I. & Onushchenko A. A. Quantum size effect in three dimensional microscopic semiconductor crystals. JETP Lett. 34, 345 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- Prawer S. & Greentree A. D. Diamond for quantum computing. Science 320, 1601–1602 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtsiefer C., Oberparleiter M. & Weinfurter H. High-efficiency entangled photon pair collection in type-II parametric fluorescence. Phys. Rev. A 64, 23802 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Nagata T., Okamoto R., O'Brien J. L., Sasaki K. & Takeuchi S. Beating the standard quantum limit with four-entangled photons. Science 316, 726–729 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanyon B. P. et al. Towards quantum chemistry on a quantum computer. Nat. Chem. 2, 106–111 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politi A., Cryan M. J., Rarity J. G., Yu S. & O'Brien J. L. Silica-on-silicon waveguide quantum circuits. Science 320, 646–649 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peruzzo A. et al. Quantum walks of correlated photons. Science 329, 1500–1503 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Pearlman A. J., Ling A., Fan J. & Migdall A. A versatile waveguide source of photon pairs for chip-scale quantum information processing. Opt. Express 17, 6727–6740 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins M. J. et al. Low Raman-noise correlated photon-pair generation in a dispersion-engineered chalcogenide As2S3 planar waveguide. Opt. Lett. 37, 3393–3395 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takesue H. et al. Entanglement generation using silicon wire waveguide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 201108–201108 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Sharping J. E. et al. Generation of correlated photons in nanoscale silicon waveguides. Opt. Express 14, 12388–12393 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemmen S. et al. Continuous wave photon pair generation in silicon-on-insulator waveguides and ring resonators. Opt. Express 17, 16558 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada K.-I. et al. Frequency and polarization characteristics of correlated photon-pair generation using a silicon wire waveguide. IEEE JSTQE 16, 325–331 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Davanço M. et al. Telecommunications-band heralded single photons from a silicon nanophotonic chip. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 261104–261104 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Xiong C. et al. Slow-light enhanced correlated photon pair generation in a silicon photonic crystal waveguide. Opt. Lett. 36, 3413–3415 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong C. et al. Characteristics of correlated photon pairs generated in ultracompact silicon slow-light photonic crystal waveguides. IEEE JSTQE 18, 1676–1683 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Clark A. S. et al. Heralded single-photon source in a III–V photonic crystal. Opt. Lett. 38, 649–651 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong C. et al. Quantum-correlated photon pair generation in chalcogenide As2S3 waveguides. Opt. Express 18, 16206–16216 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q., Yaman F. & Agrawal G. P. Photon-pair generation in optical fibers through four-wave mixing: Role of raman scattering and pump polarization. Phys. Rev. A 75, 023803 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Husko C., Colman P., Combrié S., De Rossi A. & Wong C. W. Effect of multiphoton absorption and free carriers in slow-light photonic crystal waveguides. Opt. Lett. 36, 2239–2241 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., O'Faolain L., Rey I. & Krauss T. F. Four-wave mixing in photonic crystal waveguides: slow light enhancement and limitations. Opt. Express 19, 4458–4463 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman P. et al. Temporal solitons and pulse compression in photonic crystal waveguides. Nat. Phot. 4, 862–868 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Monat C., De Sterke M. & Eggleton B. J. Slow light enhanced nonlinear optics in periodic structures. J. of Optics 12, 104003 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Husko C. et al. Non-trivial scaling of self-phase modulation and three-photon absorption in III-V photonic crystal waveguides. Opt. Express 17, 22442–22451 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combrié S., Tran Q. V., De Rossi A., Husko C. & Colman P. High quality GaInP nonlinear photonic crystals with minimized nonlinear absorption. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 221108–221108 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Mizrahi V., DeLong K. W., Stegeman G. I., Saifi M. A. & Andrejco M. J. Two-photon absorption as a limitation to all-optical switching. Opt. Lett. 14, 1140–1142 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L. & Agrawal G. P. Impact of two-photon absorption on self-phase modulation in silicon waveguides. Opt. Lett. 32, 2031–2033 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman D. A. et al. Sensitive mid-infrared detection in wide-bandgap semiconductors using extreme non-degenerate two-photon absorption. Nat. Phot. 5, 561–565 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Santagiustina M., Someda C., Vadala G., Combrié S. & De Rossi A. Theory of slow light enhanced four-wave mixing in photonic crystal waveguides. Opt. Express 18, 21024 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda N. et al. Slow light enhanced correlated photon pair generation in photonic-crystal coupled-resonator optical waveguides. Opt. Express 21, 8596–8604 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T. J., Borselli M. & Painter O. Self-induced optical modulation of the transmission through a high-q silicon microdisk resonator. Opt. Express 14, 817–831 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melloni A., Morichetti F. & Martinelli M. Four-wave mixing and wavelength conversion in coupled-resonator optical waveguides. JOSA B 25, C87–C97 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn R. T. et al. Inherent polarization entanglement generated from a monolithic semiconductor chip. Sci. Rep. 3, 2314 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orieux A. et al. Direct Bell States Generation on a III-V Semiconductor Chip at Room Temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 160502 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussières F., Slater J. A., Godbout N. & Tittel W. Fast and simple characterization of a photon pair source. Opt. Express 16, 17060–17069 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takesue H. & Shimizu K. Effects of multiple pairs on visibility measurements of entangled photons generated by spontaneous parametric processes. Opt. Comm. 283, 276–287 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Chen J., Voss P., Sharping J. & Kumar P. All-fiber photon-pair source for quantum communications: Improved generation of correlated photons. Opt. Express 12, 3737–3744 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J., Migdall A. & Wang L. J. Efficient generation of correlated photon pairs in a microstructure fiber. Opt. Lett. 30, 3368–3370 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A. S. et al. Intrinsically narrowband pair photon generation in microstructured fibres. New J. Phys. 13, 065009 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Beck M. Comparing measurements of g(2)(0) performed with different coincidence detection techniques. JOSA B 24, 2972–2978 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Divochiy A. et al. Superconducting nanowire photon-number-resolving detector at telecommunication wavelengths. Nat. Phot. 2, 302–306 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Hadfield R. H. Single-photon detectors for optical quantum information applications. Nat. Phot. 3, 696–705 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Migdall A. L., Branning D. & Castelletto S. Tailoring single-photon and multiphoton probabilities of a single-photon on-demand source. Phys. Rev. A 66, 053805 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Ma X.-S., Zotter S., Kofler J., Jennewein T. & Zeilinger A. Experimental generation of single photons via active multiplexing. Phys. Rev. A 83, 043814 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Dolgaleva K., Ng W. C., Qian L. & Aitchison J. S. Compact highly-nonlinear AlGaAs waveguides for efficient wavelength conversion. Opt. Express 19, 12440–12455 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy J. S. et al. Cmos-compatible multiple-wavelength oscillator for on-chip optical interconnects. Nat. Phot. 4, 37–40 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Helt L. G. et al. Quantum optics of spontaneous four-wave mixing in a silicon nitride microring resonator. In: Quantum Electronics and Laser Science Conference (Optical Society of America, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- Clemmen S. et al. Generation of correlated photons in hydrogenated amorphous-silicon waveguides. Opt. Lett. 35, 3483–3485 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins M. J. et al. Integrated spatial multiplexing of heralded single-photon sources. Nat. Commun. 4:2582 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3582 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mower J. & Englund D. Efficient generation of single and entangled photons on a silicon photonic integrated chip. Phys. Rev. A 84, 052326 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Li J., White T. P., O'Faolain L., Gomez-Iglesias A. & Krauss T. F. Systematic design of flat band slow light in photonic crystal waveguides. Opt. Express 16, 6227–6232 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow A. D., Rotenberg N. & Van Driel H. M. Two-photon absorption and kerr coefficients of silicon for 850–2200. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 191104–191104 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Iglesias A., O'Brien D., O'Faolain L., Miller A. & Krauss T. F. Direct measurement of the group index of photonic crystal waveguides via fourier transform spectral interferometry. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 261107–261107 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Colman P., Combrié S., Lehoucq G. & De Rossi A. Control of dispersion in photonic crystal waveguides using group symmetry theory. Opt. Express 20, 13108–13114 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman P., Combrié S., Lehoucq G., De Rossi A. & Trillo S. Blue self-frequency shift of slow solitons and radiation locking in a line-defect waveguide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 093901 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soller B. J., Gifford D. K., Wolfe M. S. & Froggatt M. E. High resolution optical frequency domain reflectometry for characterization of components and assemblies. Opt. Express 13, 666–674 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.