Abstract

Magnesium battery is potentially a safe, cost-effective, and high energy density technology for large scale energy storage. However, the development of magnesium battery has been hindered by the limited performance and the lack of fundamental understandings of electrolytes. Here, we present a study in understanding coordination chemistry of Mg(BH4)2 in ethereal solvents. The O donor denticity, i.e. ligand strength of the ethereal solvents which act as ligands to form solvated Mg complexes, plays a significant role in enhancing coulombic efficiency of the corresponding solvated Mg complex electrolytes. A new electrolyte is developed based on Mg(BH4)2, diglyme and LiBH4. The preliminary electrochemical test results show that the new electrolyte demonstrates a close to 100% coulombic efficiency, no dendrite formation, and stable cycling performance for Mg plating/stripping and Mg insertion/de-insertion in a model cathode material Mo6S8 Chevrel phase.

Low cost and safe battery technologies are critical to both transportation and grid energy storage applications1,2,3,4. Significant efforts have been made in past years to investigate technologies beyond lithium-ion chemistry5. Magnesium batteries could potentially provide high volumetric capacity due to the divalent nature of Mg2+ (3832 mAh/cm3Mg vs. 2062 mAh/cm3Li and 1136 mAh/cm3Na), improved safety (dendrite-free Mg deposition6,7), and low cost by using earth abundant Mg element8. Significant progresses8,9,10,11 have been made since Aurbach and coworkers12 reported the first rechargeable Mg battery prototype. These include new electrolytes10,13,14,15,16,17 and recent progresses in cathode18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 and anode materials27.

Electrolytes play a pivotal role in all battery systems, particularly for Mg batteries. Conventional electrolytes by mixing Mg salts (e.g., Mg(ClO4)2) and nonaqueous solvents (e.g., propylene carbonate), a typical approach to preparing electrolytes for lithium batteries, do not produce reversible plating/stripping of Mg28,29. This is usually attributed to the nonconductive layer that is formed on Mg surface in these conventional electrolytes. This nonconductive layer is similar to the so-called "solid electrolyte interphase" (SEI) in lithium batteries but could not conduct Mg2+ probably due to the divalent nature of Mg cation30. This is fundamentally different from Li+ and Na+ systems in which the SEI in fact enables Li or Na batteries.

There are only a limited number of electrolytes that show reversible Mg plating/stripping; but many of these electrolytes contain volatile solvents such as tetrahydrofuran (THF)13,15,16 or dimethoxyethane (DME)17. Electrolytes based on less volatile or nonvolatile solvents are desired31,32. More importantly, fundamental understanding of the structure-property relationship in Mg electrolytes is critical for the design and development of new electrolytes with improved performance13,33,34. It is believed that the solution coordination structures of Mg complexes in these electrolytes are critical for reversible Mg plating/stripping, but limited information is available in the literature10,13.

Back in 1950's, Connor et al.35 reported electrochemical deposition of Mg metal from Mg(BH4)2 ethereal solutions with 90% efficiency. Recently, Mohtadi et al.17 reported reversible Mg plating/stripping in the mixed solution of Mg(BH4)2, LiBH4 and DME, in which the coulombic efficiency of 94% for Mg plating/stripping was achieved. For a metal anode, 100% coulombic efficiency is desired but very difficult to achieve; a coulombic efficiency of lower than 100% may indicate that some plated Mg metal is not dissolved during the stripping process. The stripping problem could be related to the coordination structure of Mg complexes in the electrolyte36. A stable Mg(BH4)2 coordination structure may be easier to form during Mg stripping, thus favors the stripping process and improves the coulombic efficiency. Furthermore, the stability of Mg(BH4)2 coordination structures may be related to the ligands. In literature, it has been shown that the ligand displacement in the complex Mg(BH4)2·nL (L = ligand) is achieved according to the series Et2O < THF < DME < DGM (diglyme)37, which is consistent with the chelating effect38,39,40. It is reported that the stability of the solvated Mg(BH4)2 complexes with those ligands increases with the denticity of the solvent ligands41. Mohtadi et al.17 showed a higher coulombic efficiency of Mg(BH4)2-based electrolyte in DME solvent (a bidentate ligand) than that in THF solvent (a monodendate ligand). These previous studies led us to think that alternative solvents like DGM (a tridentate ligand) could be a more donating ligand for magnesium to further improve the coulombic efficiency of Mg plating/stripping in Mg(BH4)2-based electrolyte close to 100%. More importantly, the Mg(BH4)2/glymes mixture is also a good model system in understanding the molecular structures in Mg complex electrolytes and study the structure-property relationship of Mg electrolytes.

As a result, a potentially safer electrolyte based on Mg(BH4)2 and DGM is developed (the boiling/flash points of DGM, DME, THF are 162°C/57°C, 85°C/−2°C, 66°C/−14°C, respectively). LiBH4 is also employed as an additive since it has been shown to further increase the performance in the case of Mg(BH4)2/DME17. This electrolyte with 0.1 M Mg(BH4)2 and 1.5 M LiBH4 in DGM demonstrates a close to 100% coulombic efficiency (CE) for reversible Mg plating/stripping under the preliminary electrochemical test condition — the Mg(BH4)2 concentration is limited by its solubility in DGM. A well-known Mg intercalation material Mo6S8 Chevrel phase19 is used as a model cathode to evaluate the electrolyte which shows high reversibility and stability. More importantly, we focused on the fundamental understanding of the structure-property relationship for the Mg electrolyte through the spectroscopic study of the coordination chemistry of Mg2+ with ligands (solvent and BH4−) in DGM and comparison with that in DME and THF. The performance of electrolytes was found to be strongly correlated with the coordination structures of the electrochemically active Mg2+ species in the solutions.

Results

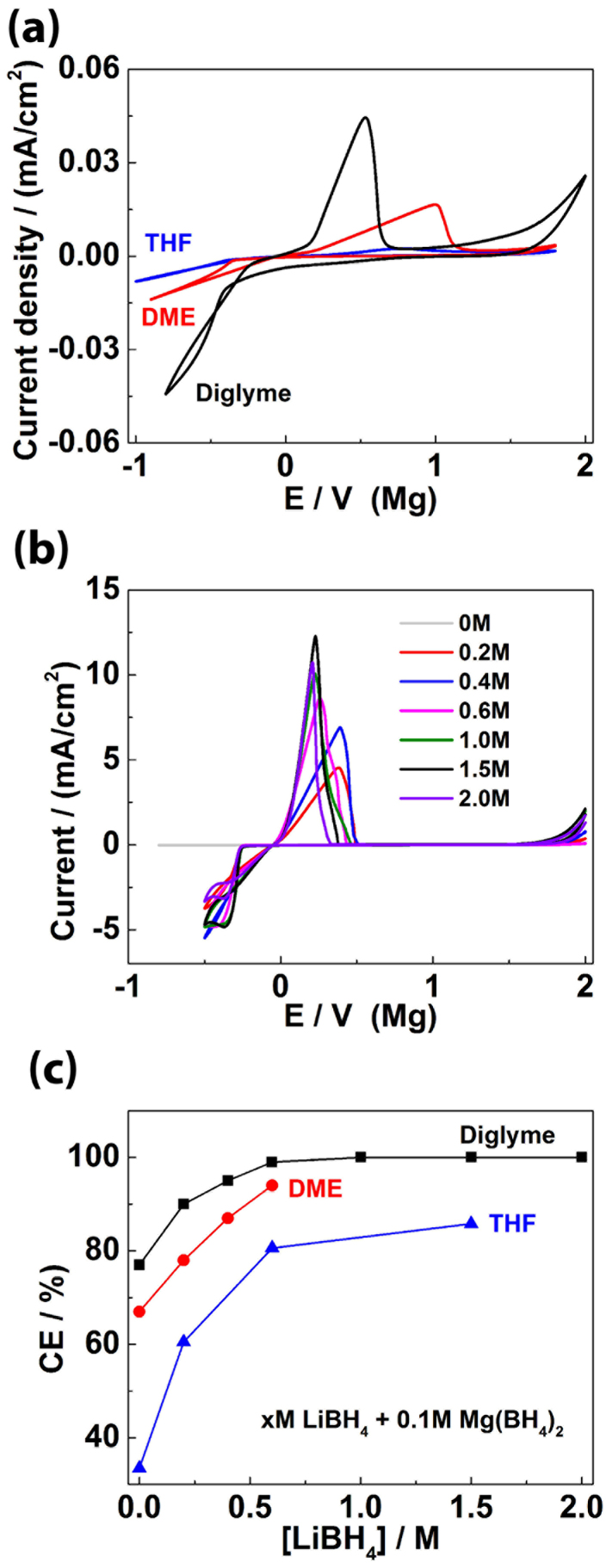

Figure 1a shows the cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of Mg electrochemical plating/stripping in electrolytes of Mg(BH4)2 dissolved in DGM, DME and THF respectively. The coulombic efficiencies which are calculated with a widely-used literature method9,17 are 77%, 67%, 34% for DGM, DME and THF respectively (see Figure S1 for examples of how to calculate coulombic efficiency); The overpotential for Mg plating/stripping in DGM is the smallest; and the current density in DGM is the highest, followed by DME and then THF. Therefore, these experimental observations clearly show that solvents have significant effects on Mg electrochemistry. We notice that the purity of Mg(BH4)2 is 95%, the 5% impurities may also affect the electrochemical performance; however, since we use the same Mg(BH4)2, the trend of comparison between different electrolytes/solvents should not be affected.

Figure 1.

(a) Cyclic voltammograms (20 mV/s) recorded on a Pt electrode in 0.01 M Mg(BH4)2 in DGM, DME and THF; (b) Cyclic voltammograms (20 mV/s) recorded on a Pt electrode in 0.1 M Mg(BH4)2/DGM with LiBH4 of various concentrations; (c) The coulombic efficiency (CE) of Mg plating/stripping of investigated electrolytes: 0.1 M Mg(BH4)2 + LiBH4 + solvent (solvent = DGM, DME, or THF), and the concentrations of LiBH4 x = 0–2.0 M.

The LiBH4 additive also changes Mg electrochemistry dramatically17. To take DGM as an example, Figure 1b shows the CVs of Mg electrochemistry in Mg(BH4)2-LiBH4/DGM electrolytes with various LiBH4 concentrations. Figure 1c summarizes the effect of solvents and LiBH4 concentration on the coulombic efficiency of Mg plating/stripping. In Figure 1b, with increasing LiBH4 concentration, the waves of both Mg plating and Mg stripping shift towards 0 V, and the peaks become narrower. This indicates enhanced reaction kinetics of both processes. The smallest voltage gap between Mg plating and stripping potentials is only ~ 0.2 V. The current density is also related to LiBH4 concentration which shows the highest value at LiBH4 concentration of 1.5 M (which is chosen for further investigation). The coulombic efficiency increases with LiBH4 concentration in all of the three solvents DGM, DME and THF (Figure 1c); for example, in DGM it increases from 77% for the electrolyte without LiBH4, to 90% for 0.2 M LiBH4, to 99% for 0.6 M LiBH4 and close to 100% when LiBH4 concentration increases to 1.0 M and beyond — we understand that more accurate and precise measurements are needed to confirm the exact coulombic efficiency42; since we use the same method to calculate coulombic efficiency for each electrolyte9,17, the trend should not be affected. More interestingly, the coulombic efficiency in DGM (with the same LiBH4 concentration) is always higher than those in DME and THF, with THF being the lowest one, which is consistent with the results without LiBH4 (Figure 1a). These indicate the significant effects of solvents and LiBH4 additive on the coulombic efficiency. We measured the conductivity of the electrolytes, for example 3.27 mS/cm, 2.07 mS/cm, 2.61 mS/cm for DGM [0.1 M Mg(BH4)2 + 1.5 M LiBH4], DME [0.1 M Mg(BH4)2 + 0.6 M LiBH4], THF [0.1 M Mg(BH4)2 + 1.5 M LiBH4], respectively, which are higher than or comparable to other Mg battery electrolytes8 and are also close to lithium battery electrolytes43,44. This also indicates that the difference in the electrolyte performance is not due to their conductivity since these three electrolytes have similar conductivity. As we will discuss later, both solvents and BH4− coordinate with Mg as ligands which affects the structure of Mg complexes, thus their performance as an electrolyte.

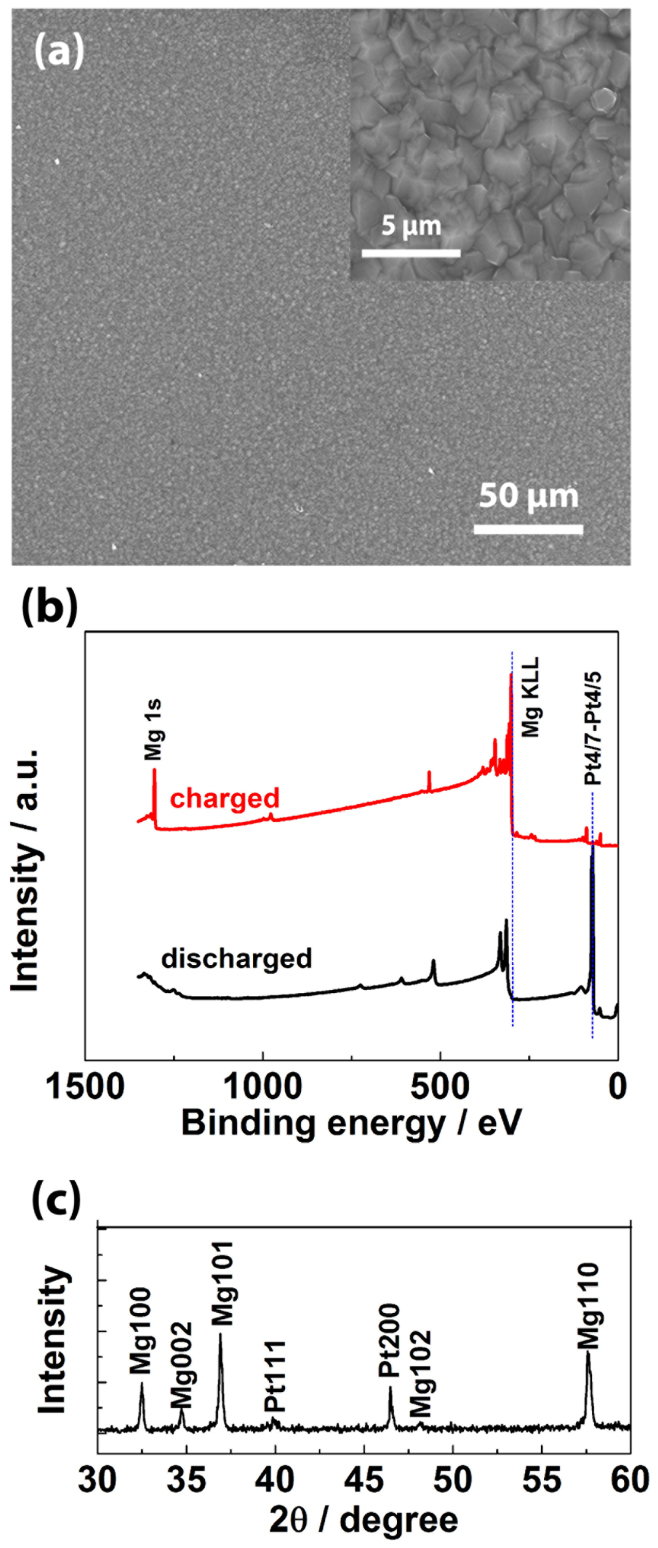

It is well-known that for a metal anode in a battery, two factors are the most critical: morphology of plated metal (smooth, dendrite-free surface desired) and coulombic efficiency (100% desired). These two problems are major challenges for lithium batteries in that they lead to severe safety issues and short lifetime of a battery45,46. Mg(BH4)2-LiBH4-DGM electrolyte shows promise in these two aspects for Mg anode. The SEM image (Figure 2a) shows a smooth, dendrite-free morphology of Mg plated from Mg(BH4)2-LiBH4-DGM electrolyte ([LiBH4] = 1.5 M). We also further investigate the reversibility of Mg plating/stripping in Mg(BH4)2-LiBH4-DGM electrolyte ([LiBH4] = 1.5 M). The XPS spectra (Figure 2b, red trace) recorded after Mg plating on Pt electrode clearly show plated Mg, and Mg completely disappeared after stripping (Figure 2b, black trace). We did not observe any detectable boron (binding energy ~ 188 eV47) or lithium (binding energy ~ 55 eV) in XPS spectra; oxygen signal (binding energy ~ 531 eV) was observed but very little carbon signal (binding energy ~ 285 eV) was observed in XPS spectra (Figure 2b). These indicate that no or very little electrolyte decomposition and no lithium deposition take place. It should be mentioned that Aurbach and coworkers have reported that ethers are stable against magnesium28,31,48,49. XRD results confirm that the plated metal is Mg (Figure 2c) and EDS results reveal no carbon element indicating no electrolyte decomposition (Figure S3). These indicate that Mg plating/stripping is highly reversible, and the coulombic efficiency is close to 100% under the test condition. Of course, more efforts are needed to further study morphology evolution during long-term cycling of Mg plating/stripping and the exact values of coulombic efficiency. But this is beyond the focus of this paper. In this work, we focus on the structure-property relationship of the Mg electrolyte.

Figure 2.

Physical characterizations of electrodes with Mg plating/stripping: (a) SEM images of plated Mg; (b) XPS recorded for a Pt plate electrode after Mg plating and Mg stripping; (c) XRD on Pt electrode after Mg plating.

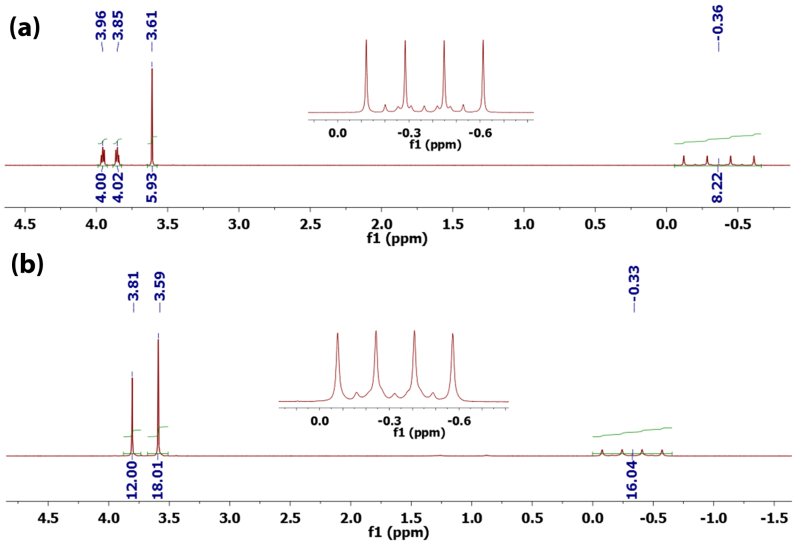

In order to understand coordination structures of Mg(BH4)2 in these solvents and correlate the structure with its performance, DGM and DME solvated Mg(BH4)2 complexes were isolated and characterized by 1H NMR and 11B NMR spectroscopies in non-coordinating CD2Cl2, which does not interrupt the structures of the solvated Mg(BH4)2. Figure 3 shows 1H NMR spectra of the solvated Mg(BH4)2 complexes with DGM and DME respectively.

Figure 3. 1H NMR spectra of Mg(BH4)2DGM (a) and Mg2(BH4)4(DME)3 (b) recorded at 22°C in CD2Cl2.

Insets are the hydride resonances. Chemical shift values and integrals are labeled at the top and the bottom of resonances respectively.

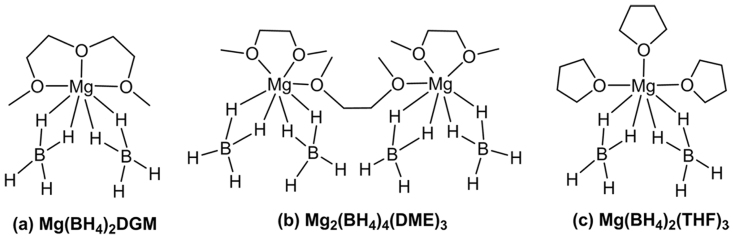

In the 1H NMR spectrum (Figure 3a), DGM solvated Mg(BH4)2 species shows proton resonances at 3.96 ppm (CH2), 3.85 ppm (CH2) and 3.61 ppm (CH3) for the coordinating DGM. As expected for the shielding effect of DGM metalation, the proton resonances of the coordinating DGM are downfield shifted in comparison to those of free DGM in CD2Cl2 (3.56, 3.49 and 3.33 ppm respectively). Due to different coupling interactions with 11B (I = 3/2) and 10B (I = 3) isotopes, two sets of hydride signals, a major quartet (JBH = 80 Hz) and a minor septet (JBH = 30 Hz) were observed at the same chemical shift, −0.36 ppm (Figure 3a, inset). Integrals of proton resonances give 1:2 ratio of DMG versus BH4− (Figure 3a), which leads to a ratio of Mg(BH4)2:DGM = 1:1. Thus, Mg(BH4)2 in DGM is formulated as seven coordinated Mg(BH4)2DGM (Figure 4a), which is consistent with the previously reported solid state structure determined by single crystal X-ray diffraction50. In Mg(BH4)2DGM, DGM is a tridentate pincer ligand and each BH4− anion coordinates with Mg via two hydrides. According to integrals of proton resonances (Figure 3b), the composition of Mg(BH4)2 complex in DME can be identified as Mg2(BH4)4DME3; by considering coordination geometry of Mg(BH4)2DGM and Mg(BH4)2THF351, Mg(BH4)2 in DME is assigned as a dimeric Mg species, Mg2(BH4)4(DME)3 (Figure 4b). In Mg2(BH4)4(DME)3, each Mg has two BH4− anions, a bidentate DME ligand and a monodentate DME ligand bridging to the other Mg. In the 11B NMR spectrum (Figure S4), Mg(BH4)2DGM and Mg2(BH4)4(DME)3 display the characteristic pentet (JBH = 80 Hz) at −42.46 and −40.37 ppm respectively. Consistent with the above structural assignments for Mg(BH4)2DGM and Mg2 (BH4)4(DME)3, previous single crystal X-ray diffraction established THF solvated Mg(BH4)2 as Mg(BH4)4(THF)3 with a similar coordination geometry (Figure 4c)51.

Figure 4. Coordination structures of Mg(BH4)2 in DGM (diglyme), DME and THF (the structure in THF is from Ref. 50,51,50,51).

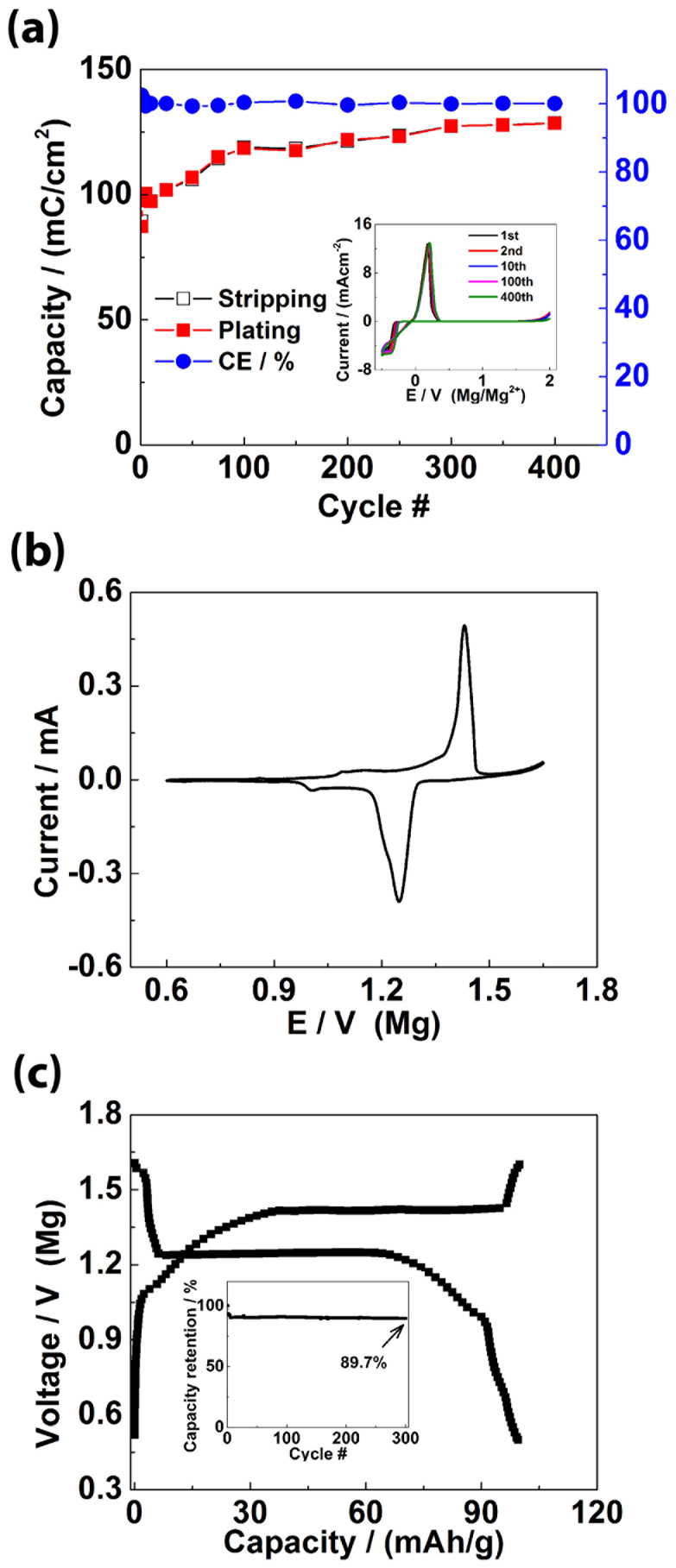

For purpose of practical applications, preliminary electrochemical tests are carried out to study the electrolyte (Mg(BH4)2-LiBH4-DGM, [LiBH4] = 1.5 M). The preliminary cycling test tells that this electrolyte is stable for Mg plating/stripping (Figure 5a); the coulombic efficiency retains close to 100% during cycling and the electric charge for Mg plating/stripping, which corresponds to the electrode capacity at such a cycling condition, increases slightly during cycling (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

(a) Cycling stability of Mg(BH4)2-LiBH4-DGM ([LiBH4] = 1.5 M) for reversible Mg plating/stripping; (b) Cyclic voltammogram (0.05 mV/s) of Mg insertion/de-insertion on the Mo6S8 Chevrel phase cathode in Mg(BH4)2-LiBH4-DGM electrolyte ([LiBH4] = 1.5 M); (c) Discharge/charge profiles of an Mg-Mo6S8 cell using the Mg(BH4)2-LiBH4-DGM electrolyte ([LiBH4] = 1.5 M) (inset: cycling stability).

A well-known Mg intercalation material Mo6S8 Chevrel phase19,52 is used as a model cathode to evaluate the new electrolyte for Mg2+ insertion/de-insertion reaction. Cyclic voltammogram in Figure 5b shows reversible Mg insertion (peak at 1.25 V) and de-insertion (peak at 1.43 V) in Mo6S8 Chevrel phase cathode. The Mg cell which consists of Mg metal anode, the new electrolyte and Mo6S8 cathode delivers an initial capacity of 99.5 mAh/g (based on Mo6S8 only) at a C/10 rate (Mo6S8 theoretical capacity is 128.8 mAh/g); the capacity drops slightly for the first a few cycles and then is stabilized for the remaining cycles with a 89.7% capacity retention for 300 cycles (Figure 5c). These indicate the new Mg(BH4)2-LiBH4-DGM electrolyte is able to support reversible Mg2+ insertion/de-insertion in cathode material and the cycling is stable.

Discussion

We believe that the performance of the electrolyte is closely related with the solution structure of Mg ions in solvents. The better performance of the new Mg(BH4)2-LiBH4-DGM electrolyte could be explained by the coordination chemistry in the electrolytes. In terms of denticity and donating strength, these coordinating solvent molecules (DGM, DME and THF) could impose different kinetic and thermodynamic influences on the Mg electrochemical process, which is essentially related with coulombic efficiency. Several aspects are rationalized below. In terms of the entropy effect, DGM as a tridentate solvent ligand, is more thermodynamically favorable than DME (and THF) in the complexion of Mg2+ during 2 electron oxidation. This is consistent with the stability of these complexes that long-chain glymes lead to more stable complex36,37,41,53. In addition, DGM complexion is also kinetically favorable since only one DGM is involved in the stripping process in comparison to 1.5 molecules of DME and 3 molecules of THF. As for the additive of LiBH4 which acts as the second coordination ligand (BH4−), from the kinetics viewpoint, its increased concentration can also speed up the stripping process at electrode surface. In brief, chelating solvent and increased BH4− concentration can significantly improve the stripping process through the synergetic effects as discussed above, which accounts for the enhanced coulombic efficiency. Other factors may also contribute to the enhanced performance. For example, the solubility of Mg(BH4)2 increases with the addition of LiBH4. This could increase the concentration of active species and the conductivity of the electrolyte, thus enhances the electrochemical performance. It should be point out that the limited concentration of Mg(BH4)2 (0.1 M) may lead to limited rate performance of Mg batteries for practical applications. But the finding of the structure-property relationship will help the discovery of new electrolytes. We are working on high concentration Mg(BH4)2 electrolytes and will report the results later.

In summary, we have developed a new electrolyte based on Mg(BH4)2, diglyme and optimized concentration of LiBH4. This new electrolyte demonstrates a close to 100% coulombic efficiency, stable cycling performance, and no dendrite formation; and the new electrolyte is able to support reversible Mg2+ insertion/de-insertion in a well-known Mg battery cathode Mo6S8 Chevrel phase. In comparison, electrolytes comprising Mg(BH4)2 in DME and THF show lower coulombic efficiencies. The solution structures of Mg(BH4)2 in different solvents are investigated and identified using NMR, which are consistent with the solid structures from single crystal X-ray diffraction in the literature50,51. Mg(BH4)2 forms coordination structures of Mg(BH4)2DGM, Mg2(BH4)4(DME)3, Mg(BH4)2(THF)3 in DGM, DME and THF respectively. DGM complexion is thermodynamically and kinetically favorable; LiBH4 additive acts as the second coordination ligand (BH4−) and its increased concentration can also speed up the stripping kinetics at electrode surface. In brief, chelating solvent and increased BH4− concentration can significantly improve the stripping process through synergetic effects, thus improve the coulombic efficiency. This structure-property relationship will help to design new electrolytes for Mg battery. For future Mg battery development, there are still significant challenges in electrolyte and electrode materials. New electrolytes using scalable chemical processes with large electrochemical window, less volatility and new cathodes using earth abundant materials with high voltage and high capacity are needed. These are under development and will be reported later.

Methods

Chemicals and material synthesis

Magnesium borohydride (Mg(BH4)2, 95%) lithium borohydride (LiBH4, 95%), anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF), magnesium ribbon (99.5%) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. THF was further dried using 3 Å molecular sieve. Battery grade dimethoxyethane (DME) and diglyme (DGM) were obtained from Novolyte Technologies, Inc. (Cleveland, US).

Chevrel phase Mo6S8 was synthesized using the molten salt synthesis method as reported in the literature by Aurbach and coworkers23. MoS2 (99% Aldrich), CuS (99.5%), and Mo (99%) were obtained from Aldrich, all in powder form. The XRD patterns of in-house made CuMo6S8 and Mo6S8 are shown in Figure S5.

Electrochemistry

Cyclic voltammetry was conducted in a standard three-electrode cell with fresh polished Mg ribbon as reference and counter electrodes which are controlled by a CHI660d workstation (CH instruments). The working electrodes are Pt, glass carbon, or stainless steel 316. The electrolytes were prepared by dissolving Mg(BH4)2 and LiBH4 in solvents. LiBH4 is soluble in diglyme (4.25 M54) and DME (0.60 M), while Mg(BH4)2 is slightly soluble. Both LiBH4 and Mg(BH4)2 are highly soluble in THF. The solubility of Mg(BH4)2 in diglyme and DME was measured by slowly adding Mg(BH4)2 into diglyme or DME, which is ~ 0.1 M/0.01 M with/without LiBH4 respectively. The electrolyte conductivity was measured using WP CP650 conductivity meter (OAKTON Instruments). The electrochemical testing was conducted in an argon filled glovebox with O2 and H2O below 0.1 ppm. The coulombic efficiency (CE) was calculated by dividing the total amount of charge for Mg stripping over the total amount of charge for Mg plating (see examples in Figure S1), which is a widely-used method for CE measurement in literature9,17.

Prototype rechargeable Mg batteries comprising a fresh polished Mg disk anode, a Mo6S8-carbon composite cathode and a separator (glass fiber B) soaked in the electrolyte solution, were tested in coin type cells (standard 2030 parts from NRC Canada). The Mo6S8-carbon composite electrode slurry was prepared by mixing 80 wt% active material (Mo6S8), 10 wt% super-C carbon powder and 10 wt% poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) dissolved in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone. The slurry was coated onto carbon paper substrate.

Physicochemical characterization

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)

Excess Mg(BH4)2 was added to 2 mL DGM (diglyme) to prepare a saturated solution. After filtering off insoluble Mg(BH4)2, the clean solution was stirred for 30 min and then mixed with 30 mL pentane to precipitate Mg(BH4)2DGM complex as white powder. The white powder was washed with pentane (10 mL) three times and then dried by vacuum. The white powder was dissolved in CD2Cl2 to record NMR spectra. 1H and 11B NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Inova spectrometer (500 MHz for 1H) at 22°C. 1H NMR (CD2Cl2, ppm):3.96 (m, 4 H, CH2), 3.85 (m, 4 H, CH4), 3.61 (s, 6 H, CH3), −0.36 (quartet, JBH = 80 Hz, septet (JBH = 30 Hz), 8 H, BH4); 11B NMR (CD2Cl2, ppm): −42.46 (pentet, JBH = 80 Hz). The preparation for Mg2(BH4)4DME3 complex was conducted in a similar manner. 1H NMR (CD2Cl2, ppm): 3.81 (s, 12 H, CH4), 3.59 (s, 18 H, CH3), −0.33 (quartet, JBH = 80 Hz, septet (JBH = 30 Hz), 16 H, BH4); 11B NMR (CD2Cl2, ppm): −40.37 (pentet, JBH = 80 Hz).

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)

was measured on a Physical Electronics Quantum 2000 Scanning ESCA Microprobe with a 16 element multichannel detector. This system uses a focused monochromatic Al Kα X-ray (1486.7 eV) source and a spherical section analyzer. The X-ray beam used was a 100 W, 100 μm diameter beam that was rastered over a 1.3 mm × 0.2 mm rectangle on the sample. The X-ray beam is incident normal to the sample and the photoelectron detector was at 45° off-normal using an analyzer angular acceptance width of 20° × 20°. Wide-scan data were collected using a pass energy of 117.4 eV. For the Ag3d5/2 line, these conditions produce FWHM of better than 1.6 eV. High energy resolution spectra were collected using a pass energy of 46.95 eV. For the Ag3d5/2 line, these conditions produced FWHM of better than 0.98 eV. The binding energy (BE) scale was calibrated using the Cu2p3/2 feature at 932.62 ± 0.05 eV and Au4f at 83.96 ± 0.05 eV for known standards. The detection limit of XPS is 0.3atom%.

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

The X-ray diffraction patterns were obtained using a Philips Xpert X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation at λ = 1.54 Å. Samples were sealed in a XRD sample holder which prevents oxygen and moisture from contacting samples.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

images were collected on a JEOL 5900 scanning electron microscope equipped with an EDAX energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDS) system. The detection limit of EDS is 0.5atom%.

Before XPS, XRD and SEM measurements, all samples were washed with THF and dried in glovebox antechamber under vacuum for overnight.

Author Contributions

Y.Y.S. and J.L. conceived and designed this work. Y.Y.S., T.B.L., G.S.L., M.G., Z.M.N., M.E., D.P.L. and C.M.W. performed the experiment, acquired and analyzed the data. Y.Y.S., T.B.L. and J.L. wrote the paper. G.S.L., J.X., C.M.W. and J.G.Z. revised the manuscript, and all authors participated in the discussion of this work.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary information

Acknowledgments

This work was primarily supported as part of the Joint Center for Energy Storage Research (JCESR), an Energy Innovation Hub funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences. The authors would also like to acknowledge the support from Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) Laboratory Directed Research and Development program for synthesizing the cathode material. The XPS, SEM, and NMR characterization was conducted in the William R. Wiley Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory (EMSL), a national scientific user facility sponsored by DOE's Office of Biological and Environmental Research and located at PNNL. PNNL is operated by Battelle for the Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC05-76RLO1830.

References

- Liu J. et al. Materials science and materials chemistry for large scale electrochemical energy storage: from transportation to electrical grid. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 929–946 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. G. et al. Electrochemical energy storage for green grid. Chem. Rev. 111, 3577–3613 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce P. G., Scrosati B. & Tarascon J. M. Nanomaterials for rechargeable lithium batteries. Angew. Chem.-Int. Edit. 47, 2930–2946 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn B., Kamath H. & Tarascon J. M. Electrical energy storage for the grid: a battery of choices. Science 334, 928–935 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce P. G., Freunberger S. A., Hardwick L. J. & Tarascon J. M. Li-O2 and Li-S batteries with high energy storage. Nat. Mater. 11, 19–29 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui M. Study on electrochemically deposited Mg metal. J. Power Sources 196, 7048–7055 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Ling C., Banerjee D. & Matsui M. Study of the electrochemical deposition of Mg in the atomic level: why it prefers the non-dendritic morphology. Electrochim. Acta 76, 270–274 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Yoo H. D. et al. Mg rechargeable batteries: an on-going challenge. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 2265–2279 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Aurbach D. et al. Progress in rechargeable magnesium battery technology. Adv. Mater. 19, 4260–4267 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Muldoon J. et al. Electrolyte roadblocks to a magnesium rechargeable battery. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 5941–5950 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Lv D. P. et al. A scientific study of current collectors for Mg batteries in Mg(AlCl2EtBu)2/THF electrolyte. J. Electrochem. Soc. 160, A351–A355 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Aurbach D. et al. Prototype systems for rechargeable magnesium batteries. Nature 407, 724–727 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pour N., Gofer Y., Major D. T. & Aurbach D. Structural analysis of electrolyte solutions for rechargeable Mg batteries by stereoscopic means and DFT calculations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 6270–6278 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizrahi O. et al. Electrolyte solutions with a wide electrochemical window for recharge magnesium batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 155, A103–A109 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y. S. et al. Boron-based electrolyte solutions with wide electrochemical windows for rechargeable magnesium batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 9100–9106 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. S. et al. Structure and compatibility of a magnesium electrolyte with a sulphur cathode. Nat. Commun. 2, 427 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohtadi R., Matsui M., Arthur T. S. & Hwang S. J. Magnesium borohydride: from hydrogen storage to magnesium battery. Angew. Chem.-Int. Edit. 51, 9780–9783 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi E., Gofer Y. & Aurbach D. On the way to rechargeable mg batteries: the challenge of new cathode materials. Chem. Mat. 22, 860–868 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Levi E., Gershinsky G., Aurbach D., Isnard O. & Ceder G. New insight on the unusually high ionic mobility in chevrel phases. Chem. Mat. 21, 1390–1399 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y. P. et al. Magnesium cobalt silicate materials for reversible magnesium ion storage. Electrochim. Acta 66, 75–81 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Nuli Y. N., Yang J., Li Y. S. & Wang J. L. Mesoporous magnesium manganese silicate as cathode materials for rechargeable magnesium batteries. Chem. Commun. 46, 3794–3796 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inamoto M., Kurihara H. & Yajima T. Electrode performance of vanadium pentoxide xerogel prepared by microwave irradiation as an active cathode material for rechargeable magnesium batteries. Electrochemistry 80, 421–422 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Lancry E., Levi E., Mitelman A., Malovany S. & Aurbach D. Molten salt synthesis (MSS) of Cu2Mo6S8- new way for large-scale production of chevrel phases. J. Solid State Chem. 179, 1879–1882 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- NuLi Y. N., Zheng Y. P., Wang Y., Yang J. & Wang J. L. Electrochemical intercalation of Mg2+ in 3d hierarchically porous magnesium cobalt silicate and its application as an advanced cathode material in rechargeable magnesium batteries. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 12437–12443 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y. L. et al. Rechargeable Mg batteries with graphene-like MoS2 cathode and ultrasmall Mg nanoparticle anode. Adv. Mater. 23, 640–643 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S. Q., Li D. X., Zhang T. R., Tao Z. L. & Chen J. First-principles study of zigzag MoS2 nanoribbon as a promising cathode material for rechargeable Mg batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 1307–1312 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Singh N., Arthur T. S., Ling C., Matsui M. & Mizuno F. A high energy-density tin anode for rechargeable magnesium-ion batteries. Chem. Commun. 49, 149–151 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z., Schechter A., Moshkovich M. & Aurbach D. On the electrochemical behavior of magnesium electrodes in polar aprotic electrolyte solutions. J. Electroanal. Chem. 466, 203–217 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Gregory T. D., Hoffman R. J. & Winterton R. C. Nonaqueous electrochemistry of magnesium - applications to energy storage. J. Electrochem. Soc. 137, 775–780 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Aurbach D. et al. A comparison between the electrochemical behavior of reversible magnesium and lithium electrodes. J. Power Sources 97–8, 269–273 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Aurbach D. et al. A short review on the comparison between Li battery systems and rechargeable magnesium battery technology. J. Power Sources 97–98, 28–32 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Aurbach D. et al. Electrolyte solutions for rechargeable magnesium batteries based on organomagnesium chloroaluminate complexes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 149, A115–A121 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Aurbach D., Moshkovich M., Schechter A. & Turgeman R. Magnesium deposition and dissolution processes in ethereal grignard salt solutions using simultaneous EQCM-EIS and in situ FTIR spectroscopy. Electrochem. Solid State Lett. 3, 31–34 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Aurbach D., Schechter A., Moshkovich M. & Cohen Y. On the mechanisms of reversible magnesium deposition processes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 148, A1004–A1014 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Connor J. H., Reid W. E. & Wood G. B. Electrodeposition of metals from organic solutions. 5. electrodeposition of magnesium and magnesium alloys. J. Electrochem. Soc. 104, 38–41 (1957). [Google Scholar]

- Poonia N. S. & Bajaj A. V. Coordination chemistry of alkali and alkaline-earth cations. Chem. Rev. 79, 389–445 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- Bremer M., Linti G., Noth H., Thomann-Albach M. & Wagner G. Metal tetrahydroborates and tetrahydroborato metalates. 30[1] solvates of alcoholato-, phenolato-, and bis(trimethylsilyl)amido-magnesium tetrahydroborates XMgBH4(Ln). Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 631, 683–697 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzenbach G. Der chelateffekt. Helv. Chim. Acta 35, 2344–2363 (1952). [Google Scholar]

- Breslow R., Belvedere S., Gershell L. & Leung D. The chelate effect in binding, catalysis, and chemotherapy. Pure Appl. Chem. 72, 333–342 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Adamson A. W. A proposed approach to the chelate effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 76, 1578–1579 (1954). [Google Scholar]

- Vantruong N. et al. Selectivities and thermodynamic parameters of alkali-metal and alkaline-earth-metal complexes of polyethylene-glycol dimethyl ethers in methanol and acetonitrile. Inorg. Chim. Acta 184, 59–65 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Bond T. M., Burns J. C., Stevens D. A., Dahn H. M. & Dahn J. R. Improving precision and accuracy in coulombic efficiency measurements of Li-ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 160, A521–A527 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Xu K. Nonaqueous liquid electrolytes for lithium-based rechargeable batteries. Chem. Rev. 104, 4303–4417 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley J. T. et al. Conductivity of electrolytes for rechargeable lithium batteries. J. Power Sources 35, 59–82 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Aurbach D., Zinigrad E., Cohen Y. & Teller H. A short review of failure mechanisms of lithium metal and lithiated graphite anodes in liquid electrolyte solutions. Solid State Ion. 148, 405–416 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Aurbach D., Zinigrad E., Teller H. & Dan P. Factors which limit the cycle life of rechargeable lithium (metal) batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 147, 1274–1279 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Il'inchik E. A. Standards for X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy of boron compounds. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 75, 883–891 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Gofer Y., Turgeman R., Cohen H. & Aurbach D. XPS investigation of surface chemistry of magnesium electrodes in contact with organic solutions of organochloroaluminate complex salts. Langmuir 19, 2344–2348 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Viestfrid Y., Levi M. D., Gofer Y. & Aurbach D. Microelectrode studies of reversible Mg deposition in THF solutions containing complexes of alkylaluminum chlorides and dialkylmagnesium. J. Electroanal. Chem. 576, 183–195 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Lobkovskii E. B., Titov L. V., Levicheva M. D. & Chekhlov A. N. Crystal and molecular-structure of magnesium borohydride diglymate. J. Struct. Chem. 31, 506–508 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Lobkovskii E. B., Titov L. V., Psikha S. B., Antipin M. Y. & Struchkov Y. T. X-ray crystallographic investigation of crystals of bis(tetrahydroborato)tris(tetrahydrofuranato)magnesium. J. Struct. Chem. 23, 644–646 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Levi E. et al. Phase diagram of Mg insertion into chevrel phases, MgxMo6T8 (T = S, Se), 2. the crystal structure of triclinic MgMo6Se8. Chem. Mat. 18, 3705–3714 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan L. L., Wong K. H. & Smid J. Complexation of lithium, sodium, and potassium carbanion pairs with polyglycol dimethy ethers (glymes), effect of chain length and temperature. J Am. Chem. Soc. 92, 1955–1963 (1970). [Google Scholar]

- Brown H. C., Narasimhan S. & Choi Y. M. Selective reductions. 30. effect of cation and solvent on the reactivity of saline borohydrides for reduction of carboxylic esters - improved procedures for the conversion of esters to alcohols by metal borohydrides. J. Org. Chem. 47, 4702–4708 (1982). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information