Abstract

Distinct peptide-MHC-II complexes, recognised by Type A and B CD4+ T-cell subsets, are generated when antigen is loaded in different intracellular compartments. Conventional Type A T cells recognize their peptide epitope regardless of the route of processing, whereas unconventional Type B T cells only recognise exogenously supplied peptide. Type B T cells are implicated in autoimmune conditions and may break tolerance by escaping negative selection. Here we show that Salmonella differentially influences presentation of antigen to Type A and B T cells. Infection of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) reduced presentation of antigen to Type A T cells but enhanced presentation of exogenous peptide to Type B T cells. Exposure to S. Typhimurium was sufficient to enhance Type B T-cell activation. Salmonella Typhimurium infection reduced surface expression of MHC-II, by an invariant chain-independent trafficking mechanism, resulting in accumulation of MHC-II in multi-vesicular bodies. Reduced MHC-II surface expression in S. Typhimurium-infected BMDCs correlated with reduced antigen presentation to Type A T cells. Salmonella infection is implicated in reactive arthritis. Therefore, polarisation of antigen presentation towards a Type B response by Salmonella may be a predisposing factor in autoimmune conditions such as reactive arthritis.

Keywords: Autoimmunity, Bacterial Infections, CD4 T cells, Tolerance

Introduction

Salmonella enterica is an intracellular pathogen that survives and replicates in phagocytic cells within specialised compartments known as Salmonella-containing vacuoles (SCV) [1]. Following oral ingestion, Salmonella crosses the intestinal epithelium by invasion of non-phagocytic enterocytes or via M cells overlying Peyer's Patches [2]. Alternatively, Salmonella is directly taken up by DCs that intercalate between intestinal epithelial cells [3]. Salmonella can disseminate extracellularly or be engulfed by macrophages in the submucosa [2]. Salmonella pathogenicity islands (SPI) are critically important for virulence. They encode type III secretion systems (T3SS) that inject bacterial effector proteins into host cells. T3SS-1 is encoded within SPI1 and is required for invasion of host cells, whereas T3SS-2 is encoded by SPI2 and contributes to immune evasion and maintenance of the SCV by intracellular Salmonella [4]. Salmonella enterica serovars such as Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) and Enteritidis cause rapid-onset gastroenteritis in a range of species, whereas serovars such as Typhi and Paratyphi cause systemic typhoid fever in humans. Salmonella Typhi can establish life-long infection of the gall bladder in 1–4% of patients. These typhoid carriers exhibit normal antibody responses to Salmonella Typhi antigens but have an impaired cell-mediated immune response [5].

MHC-II molecules play an essential role in the cell-mediated immune response by presenting antigenic peptides to CD4+ T cells. Immature MHC-II molecules are assembled in the ER and are composed of α and β chains in complex with preformed trimers of invariant chain (Ii) [6]. Ii occupies the peptide-binding groove of MHC-II to prevent premature peptide binding and chaperones the MHC-II complex from the ER to the endocytic pathway. Entry into the endocytic pathway is predominantly by clathrin-mediated endocytosis from the plasma membrane [7], but can also be direct from the trans-golgi network [8]. Once inside the endosomal compartments, Ii is degraded by lysosomal proteases until only CLIP is left bound in the MHC-II peptide-binding groove. HLA-DM exchanges CLIP for antigenic peptides in late endosomal compartments and mature peptide-MHC-II (pMHC-II) complexes are then exported to the cell surface [9]. In DCs, ubiquitination of a conserved lysine residue in the β chain cytoplasmic tail regulates surface expression and targeting of pMHC-II into late endosomal multi-vesicular bodies (MVBs) [10].

Formation of pMHC-II conformers from native protein occurs primarily in HLA-DM+ late endosomes and generates stable complexes that are recognised by conventional Type A CD4+ T cells. In contrast, loading of exogenous peptide can occur throughout the endosomal pathway or at the cell surface and can generate pMHC-II conformers that are recognised by conventional Type A and unconventional Type B CD4+ T cells [11]. Type B T cells only recognise exogenous peptide and not the identical peptide when processed from protein. As a consequence, Type B T cells escape negative selection and are implicated in autoimmune conditions. In the NOD mouse model, Type B insulin-reactive T cells are pathogenic and trigger diabetes in adoptive transfer experiments [12]. Type B T cells constitute 30–50% of the T-cell repertoire [13], and phenotypically may resemble either Th1 or Th2 CD4+ T cells [12].

Salmonella is reported to interfere with MHC-II antigen processing and presentation to CD4+ T cells [14–17]. The relevance of these mechanisms in vivo is not clear as CD4+ T-cell priming has also been observed in mouse models of Salmonella infection [18–21]. We have previously shown that Salmonella infection of human DCs results in polyubiquitination and reduced surface expression of MHC-II [15, 22]. In this study, we investigate how Salmonella influences MHC-II trafficking and presentation of antigen to Type A and B CD4+ T cells.

Results

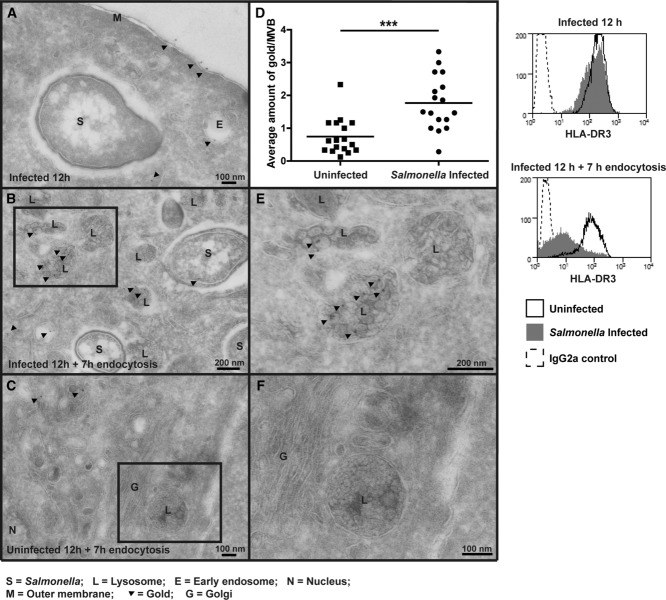

MHC-II accumulates in MVBs in Salmonella-infected cells

MHC-II is specifically removed from the surface of Salmonella-infected cells and accumulates in intracellular vesicles that resemble HLA-DM+ LAMP-1+ EEA− peptide-loading compartments [15, 22]. To better define the nature of these compartments, MHC-II localisation was assessed in Salmonella-infected MelJuSo cells, as the endocytic pathway is well characterised in this human epithelial-like melanoma cell line [23]. Cell surface HLA-DR was labelled with the monoclonal antibody L243 and after internalisation was visualised by cryo-immunoelectron microscopy.

HLA-DR was predominantly detected at the cell surface at 12 h post-infection in both uninfected (data not shown) and Salmonella-infected cells (Fig. 1A). Between 12 and 20 h post-infection, HLA-DR was endocytosed and distributed within early endosomes, MVBs and at the cell surface in uninfected cells (Fig. 1C and F). In Salmonella-infected cells, there was a twofold greater accumulation of HLA-DR in MVBs compared with uninfected cells (Fig. 1B, D and E). The internalised MHC-II was not significantly associated with the SCV but localised to MVBs that most likely represent conventional MHC-II containing compartments found in the Salmonella-infected cells. There were fewer MVBs in uninfected cells suggesting that Salmonella may enlarge this compartment through accumulation of intracellular HLA-DR (data not shown). Since Salmonella infection results in polyubiquitination of MHC-II, and ubiquitination regulates sorting of MHC-II at MVBs [10, 15], these results may suggest that Salmonella-induced ubiquitination of MHC-II enhances accumulation in MVBs to prevent recycling of mature MHC-II to the cell surface.

Figure 1.

MHC-II accumulates in MVBs in Salmonella-infected cells. MelJuSo were infected for 20 min with invasive GFP-S. Typhimurium (MOI 50). Cell surface MHC-II was labelled (L243) at 12 h post-infection and then cells were fixed (A) or further incubated until 20 h post-infection before fixation (B, C, E and F). Cell sections were processed for cryo-immunoelectron microscopy and HLA-DR localisation was visualised with Protein A-gold (10 nm). (D) Graph represents average amount of gold (HLA-DR)/MVB in each cell analysed. Average amount of gold/MVB was calculated for at least 15 cells per condition and comparison of distributions was assessed by unpaired two-tailed t-test. Boxed areas from (B) and (C) are magnified twofold in (E) and (F), respectively. Histograms show surface HLA-DR measured by flow cytometry in infected and uninfected MelJuSo at time points indicated. Refer to Supporting Information Fig. 1A for gating strategy. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

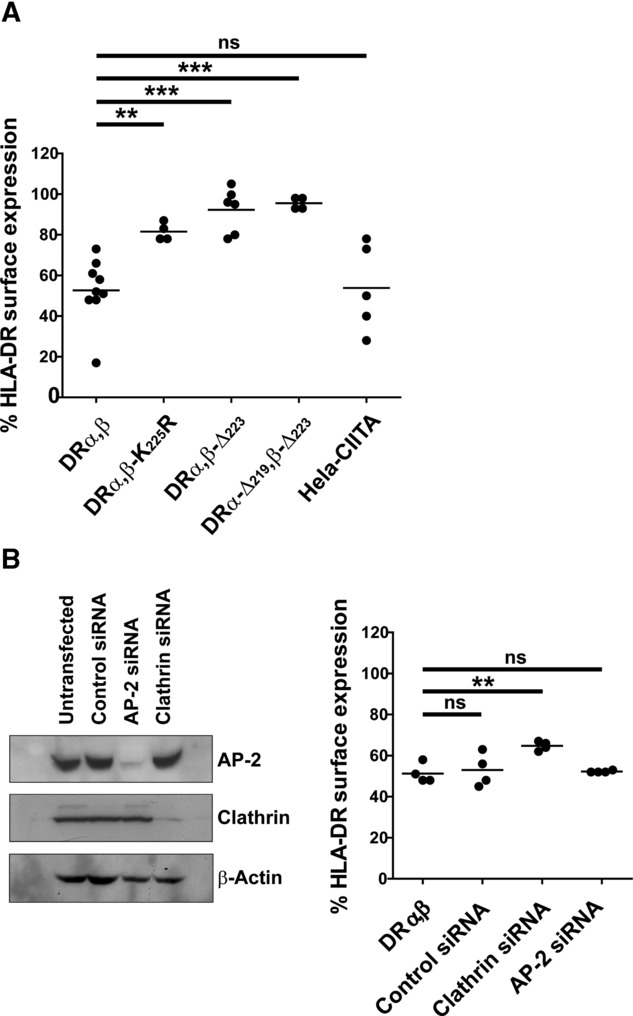

MHC-II down-regulation by Salmonella requires clathrin but not invariant chain-directed trafficking

To determine whether Ii-directed trafficking of MHC-II is required by Salmonella to regulate MHC-II surface expression, we generated HeLa cell transfectants stably expressing HLA-DR, but lacking endogenous Ii. There was no significant difference in the extent of HLA-DR down-regulation by Salmonella in HeLa cells expressing CIITA (Ii-positive) and HeLa cells transduced with HLA-DR (Ii-negative) (Fig. 2A). As expected, HLA-DR dimers that lacked the DRβ cytoplasmic tail (DRα-Δ219,β-Δ223 and DRα,β-Δ223) or with a lysine to arginine mutation in the β chain ubiquitination site (DRα,β-K225R), were not down-regulated by Salmonella (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

MHC-II down-regulation by Salmonella requires clathrin but not invariant chain-directed trafficking. (A) HeLa cells stably expressing HLA-DR WT (DRα,β) and cytoplasmic tail mutants were generated. HLA-DR surface expression was assessed by flow cytometry at 20 h post-infection with invasive GFP-S. Typhimurium and compared with HeLa-CIITA (Ii positive) cells. Refer to Supporting Information Fig. 1A and B for gating strategy and representative flow cytometry data. Graph shows percent of normal HLA-DR surface expression in uninfected (GFP-negative) cells combined from at least four independent experiments. (B) HeLa cells stably expressing HLA-DR WT (DRα,β)(Ii negative) were transfected with AP-2, clathrin or control siRNAs. Cells were infected with invasive GFP-S. Typhimurium after 5 days of AP-2 or clathrin depletion and surface HLA-DR was assessed as described in (A). Western blot shows AP-2 and clathrin depletion from representative cell lysates after 5 days of siRNA treatment. The loading control is β-actin. Graph shows percent of normal surface HLA-DR expression in uninfected (GFP negative) cells combined from four independent experiments. Comparison of distributions was performed by unpaired (A) or paired (B) two-tailed t-tests.

Endocytosis of pMHC-II is clathrin, AP-2 and dynamin independent [24]. To examine whether HLA-DR down-regulation by Salmonella requires AP-2 and clathrin, Ii-negative HeLa cells stably expressing HLA-DR were transfected with AP-2 and clathrin siRNA oligonucleotides and surface expression of HLA-DR was assessed by flow cytometry. In the absence of Ii, siRNA knockdown of clathrin, but not AP-2, reduced HLA-DR down-regulation by Salmonella (Fig. 2B, right panel). These data show that down-regulation of pMHC-II surface expression by Salmonella requires clathrin but was independent of Ii-directed trafficking and AP-2.

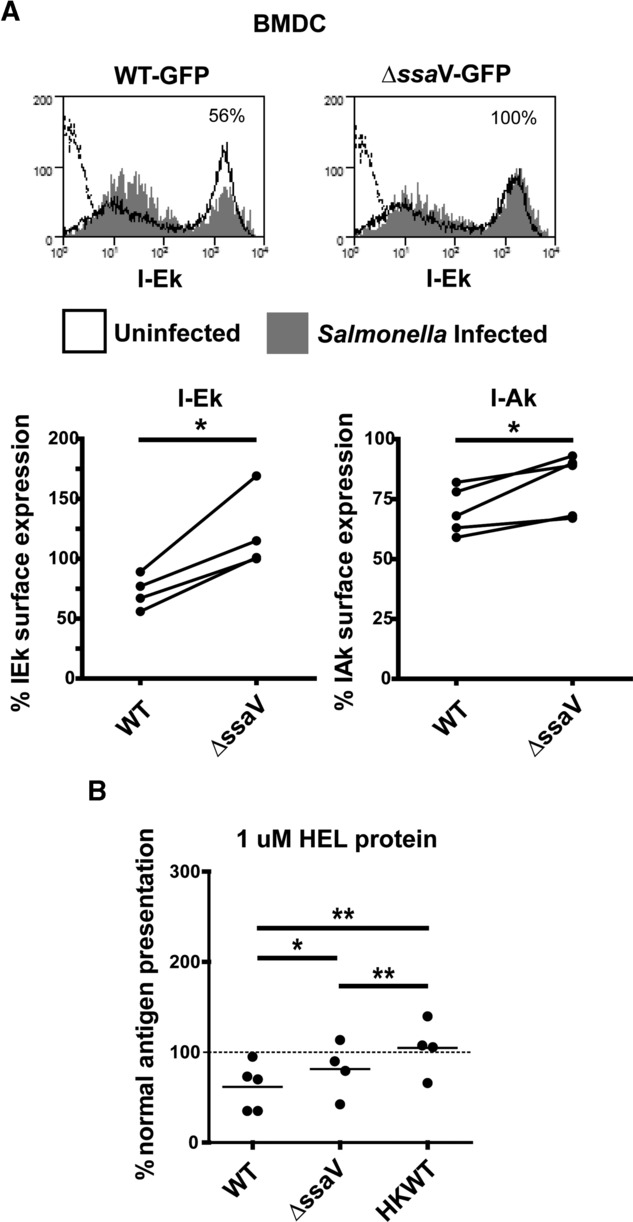

Salmonella down-regulates murine MHC-II surface expression and antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells

To examine the effect of Salmonella on T-cell presentation, we first exposed murine BMDCs to GFP-expressing Salmonella and examined surface I-A and I-E expression. Exposure to Salmonella increased overall I-Ak and I-Ek surface expression, consistent with BMDC activation and maturation [25] (data not shown). Infection of BMDCs with WT Salmonella reduced surface expression of I-Ak and I-Ek. I-Ak and I-Ek down-regulation was not detected following infection with ΔssaV Salmonella (Fig. 3A), as observed previously for HLA-DR [15]. This indicated that the SPI2 effector system was also required to regulate MHC-II surface expression in murine cells. Comparable I-A and I-E down-regulation was also seen for the b and d haplotypes (data not shown). MHC-II down-regulation was not detected in either human monocyte-derived macrophages, or a murine macrophage cell line, RAW264.7-CIITA (Supporting Information Fig. 2). The reason for this is unknown but may reflect functional differences between DCs and macrophages [26].

Figure 3.

Salmonella downregulates I-A and I-E surface expression and presentation of antigen to CD4+ T cells. (A) BMDCs were infected with opsonised GFP-S. Typhimurium (MOI 10) then I-Ak (OX6) and I-Ek (14.4.4s) surface expression was compared in infected (GFP positive) and uninfected (GFP negative) CD11c/CD11b+ BMDCs by flow cytometry. Refer to Supporting Information Fig. 1A for gating strategy. Histograms (upper panels) show I-Ek surface expression in infected and uninfected BMDCs from a representative of at least four independent experiments. Graphs (lower panels) show percent of normal (GFP negative) I-Ak or I-Ek surface expression combined from four independent preparations of BMDCs infected with WT or SPI2-deficient (ΔssaV) S. Typhimurium. (B) BMDCs (in triplicate) were uninfected or infected with opsonised WT, HKWT or ΔssaV S. Typhimurium (MOI 10). From 20 h post-infection, cells were incubated with HEL protein and Type A CD4+ T hybridoma cells (3A9) at a ratio of 5 T cells: 1 BMDC. After 24 h, culture supernatants were harvested and T-cell activation was quantified by IL-2 ELISA. Graph shows percent of normal mean (uninfected) I-Ak-dependent HEL presentation to Type A T cells combined from at least four independent experiments. Antigen presentation in uninfected BMDCs is shown as a dashed line. Comparison of distributions was performed by paired two-tailed t-tests.

To assess antigen presentation in the context of Salmonella infection we analysed I-Ak-dependent presentation of the model antigen hen egg lysozyme (HEL) by BMDCs to a CD4+ T-cell hybridoma expressing a HEL-specific TCR (3A9). T-cell hybridomas do not require co-stimulation and therefore pMHC-II levels should directly correlate with the extent of antigen presentation. BMDCs were used because they can be generated in large quantities and they resemble the myeloid CD11b+ DCs present in the sub-epithelial dome of murine Peyer's patches where Salmonella internalise early after oral infection in vivo [3, 27].

Incubation of BMDCs with exogenous HEL protein resulted in dose-dependent HEL-specific T-cell activation, as measured by IL-2 production (data not shown). After infection of BMDCs with Salmonella a reduction in T-cell activation was observed (Fig. 3B), in line with previous observations using exogenous antigen [14, 28]. The reduction in T-cell activation was SPI2 dependent, although the effect was subtle. A MOI of ten bacteria to one BMDC was used as this does not induce significant NO production by the BMDCs (confirmed by Griess assay; data not shown) [14]. Infection with an equal number of heat-killed (HK) Salmonella had no influence on T-cell activation confirming that viable bacteria are required to inhibit antigen presentation in the absence of NO. These data show that down-regulation of MHC-II surface expression by Salmonella correlates with reduced presentation of antigen to CD4+ T cells.

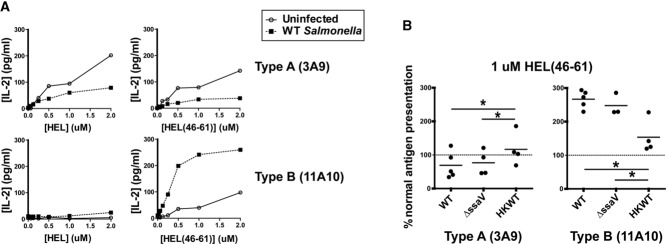

Salmonella enhances presentation of exogenous peptide to Type B CD4+ T cells

To determine whether Salmonella also influenced presentation of antigen to Type B CD4+ T cells, we compared I-Ak-dependent presentation of exogenous HEL protein and HEL46–61 peptide by BMDCs to a Type A T-cell hybridoma (3A9) and a Type B T-cell hybridoma (11A10) with identical peptide specificity.

In line with previous publications, incubation of BMDCs with exogenous HEL protein or HEL46–61 peptide resulted in dose-dependent HEL-specific Type A T-cell activation, whereas only incubation with exogenous HEL46–61 peptide resulted in equivalent activation of Type B T cells (Fig. 4A, open circles) [11]. Infection of BMDCs with WT Salmonella inhibited presentation of both exogenous HEL protein and HEL46–61 peptide to Type A T cells. Intriguingly, WT Salmonella infection caused a dramatic increase in the presentation of exogenous HEL46–61 peptide to Type B T cells, but had little effect on presentation of HEL protein (Fig. 4A). Unlike inhibition of Type A T-cell activation by Salmonella, enhanced presentation of HEL46–61 peptide to Type B T cells was not SPI2 (ssaV) dependent (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, infection with an equal number of HK Salmonella had no effect on Type A T-cell activation but subtly increased Type B T-cell activation (Fig. 4B). These data show that Salmonella influenced antigen presentation in several distinct ways. Most dramatically Salmonella infection resulted in elevated presentation of exogenous peptide to Type B T cells. This was associated with a reduction in presentation of peptide or protein antigen to Type A T cells.

Figure 4.

Salmonella infection enhances presentation of exogenous peptide to Type B T cells. BMDCs (in triplicate) were infected with opsonised WT (A and B), SPI2-deficient (ΔssaV) (B) or HKWT (B) GFP-S. Typhimurium (MOI 10). From 20 h post-infection, cells were incubated with HEL protein or HEL46–61 peptide and 3A9 (Type A) or 11A10 (Type B) T hybridoma cells at a ratio of 5 T cells: 1 BMDC. After 24 h, culture supernatants were harvested and T-cell activation was quantified by IL-2 ELISA. (A) Graphs show mean IL-2 concentration from a representative of at least four independent experiments. Error bars represent SD. (B) Graphs show percent of normal (uninfected) I-Ak-dependent HEL46–61 presentation to Type A or B T cells combined from at least three independent experiments. Antigen presentation in uninfected BMDCs is shown as a dashed line. Comparison of distributions was performed by paired two-tailed t-tests.

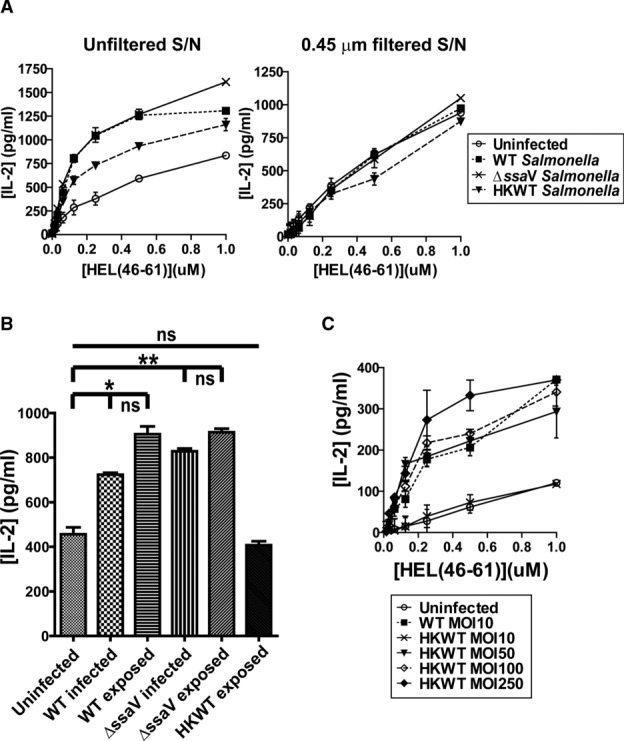

Exposure to Salmonella is sufficient to enhance presentation of exogenous peptide to Type B T cells

At the MOI used in the above experiments (MOI = 10), only 10–20% of the BMDCs were infected with Salmonella. This suggested that direct infection may not be required and that a soluble factor produced by infected BMDCs could be influencing neighbouring cells. To screen for potential soluble factors produced by Salmonella-infected BMDCs, culture supernatant was harvested from infected BMDCs at 20 h post-infection and incubated with fresh BMDCs, Type B T hybridoma cells and HEL46–61 peptide.

Incubation of fresh BMDCs with culture supernatant from Salmonella-infected BMDCs was sufficient to enhance presentation of exogenous peptide to Type B T cells (Fig. 5A). Clearance of the supernatant using a 0.45 μm filter prior to incubation with fresh BMDCs (Fig. 5A) or separation of infected BMDCs from fresh BMDCs and T cells using 0.45 μm transwells (Supporting Information Fig. 4) abrogated the effect. This suggested that whilst a component of culture supernatant from Salmonella-infected BMDCs can influence uninfected BMDCs in trans, the factor responsible was not smaller than 0.45 μm.

Figure 5.

Exposure to Salmonella is sufficient to enhance presentation of exogenous peptide to Type B T cells. BMDCs (in triplicate) were infected with opsonised WT, SPI2-deficient (ΔssaV) or HKWT GFP-S. Typhimurium (MOI 10, unless specified (C)). For antigen presentation, BMDCs were incubated with HEL46–61 peptide and 11A10 (Type B) T hybridoma cells at a ratio of 5 T cells: 1 BMDC. After 24 h, culture supernatants were harvested and T-cell activation was quantified by IL-2 ELISA. (A) At 20 h post-infection, culture supernatant was harvested and incubated with fresh BMDCs, HEL46–61 peptide and 11A10 (Type B) T cells. Where indicated, culture supernatant was filtered (0.45 μm) prior to incubation with fresh BMDCs. (B) At 20 h post-infection, GFP-S. Typhimurium-infected BMDCs were sorted from the exposed but uninfected population. Refer to Supporting Information Fig. 1A for representative gating strategy. Presentation of 0.5 μM HEL46–61 peptide to 11A10 (Type B) T cells was compared for BMDCs that were unexposed, exposed but uninfected, or infected with S. Typhimurium. Comparison of distributions was performed by unpaired two-tailed t-tests. (A–C) Data shown are the mean + SD and are representative of one out of at least four independent experiments.

Salmonella are rod-shaped bacteria, 0.5–1.5 μm in diameter and 2–5 μm in length. Clearance of culture supernatant using a 0.45 μm filter would therefore remove any intact Salmonella present. To determine whether direct exposure of BMDCs to Salmonella was sufficient to enhance presentation of exogenous peptide to Type B T cells, BMDCs were infected with GFP-expressing Salmonella and then sorted at 20 h post-infection to separate infected from exposed but uninfected populations. Presentation of HEL46–61 peptide to Type B T hybridoma cells was compared for BMDCs that were unexposed, exposed but uninfected, or exposed and infected with Salmonella, respectively.

Exposure of BMDCs to Salmonella was sufficient to enhance presentation of exogenous peptide to Type B T cells (Fig. 5B). There was no significant difference in the extent of Type B T-cell activation between sorted BMDCs that were exposed to, or infected with Salmonella. There was a consistent trend towards reduced presentation in the infected BMDCs, although the effect was subtle (Fig. 5B). Notably, presentation of peptide to Type B T cells was enhanced by HK Salmonella if the MOI was increased (Fig. 5C). This suggested that whilst viable bacteria contribute more significantly to the enhanced presentation of exogenous HEL46–61 peptide to Type B T cells observed, viability is not essential.

Discussion

We show that Salmonella infection influences MHC-II antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells by two distinct mechanisms. Intra-cellular replication of Salmonella resulted in reduced expression of pMHC-II complexes at the cell surface and altered presentation of antigen to CD4+ T cells. Most importantly, exposure of BMDCs to Salmonella resulted in enhanced presentation of exogenous peptide to Type B CD4+ T cells, which have been linked to auto-immune disease progression [12].

We first examined the influence of intracellular Salmonella on MHC-II trafficking and localisation. Using Ii-negative HeLa cells, we showed that down-regulation of MHC-II by Salmonella was independent of Ii-directed trafficking and AP-2, but required clathrin. As AP-2 is the principal adaptor protein required for formation of clathrin-coated pits at the plasma membrane [29], it is unlikely that MHC-II down-regulation by Salmonella requires the formation of clathrin-coated pits. Distinct clathrin coats are also present at the cytoplasmic face of MVBs and are proposed to concentrate cargo for subsequent incorporation into luminal vesicles [29]. In addition, sorting of pMHC-II into luminal vesicles at MVBs is regulated by ubiquitination [30]. Therefore, the requirement for clathrin by Salmonella may be related to clathrin-dependent sorting of ubiquitinated cargo at MVBs.

We next confirmed that Salmonella down-regulated surface expression of I-A and I-E in BMDCs, similar to what has been observed in human cells [15, 22]. This validated the use of murine T-cell reagents to assess antigen presentation following Salmonella infection of BMDCs. Salmonella infection of murine DCs has been reported to inhibit presentation of antigen to CD4+ T cells [14, 28]. Here we compared the influence of Salmonella on presentation of antigen to Type A and B CD4+ T-cell subsets. In contrast to the suppressive effect of Salmonella infection on presentation of both exogenous protein and peptide antigen to Type A T cells, presentation of peptide to Type B T cells was significantly enhanced. Salmonella infection did not significantly alter presentation of exogenous protein antigen to Type B T cells. This contrasts with the recent data of Strong and Unanue showing that TLR ligands have no effect on the presentation of peptide via the Type B conformer in splenic DCs [31]. This may reflect differences in antigen handling between DC subsets as reported by Lovitch et al. for presentation of native antigen to Type B T cells using LPS-stimulated BMDCs [32].

The relevance of reduced Type A presentation in relation to immunity to Salmonella infection in vivo is not clear. Whilst chronic typhoid carriers exhibit impaired humoral and cellular immunity [5], rapid priming of CD4+ T cells in mouse models of Salmonella infection was reported to elicit effective Th1 responses [21]. Regardless, priming of Type B T-cell responses does not imply any perturbation in the Th1/Th2 balance and could occur in the presence or absence of effective anti-Salmonella responses. Taken together, these data suggest that Salmonella infection polarises antigen presentation by stabilising or enhancing formation of the pMHC-II conformer recognised by Type B T cells, leading to increased Type B T-cell activation. In heavily infected BMDCs, this polarisation may be further promoted by reduced presentation of pMHC-II conformers recognised by Type A T cells.

Mere exposure to HK Salmonella or supernatant from Salmonella-infected BMDCs was sufficient to enhance presentation of exogenous peptide to Type B T cells. This phenotype is unlikely to be caused by soluble TLR ligands such as LPS and flagellin, as these are shed by Salmonella in significant amounts [33] and the effect was lost when the culture supernatant was filtered or when infected BMDCs were spatially separated from uninfected BMDCs and T cells. It is unlikely to be due to secretion of a soluble cytokine as this would also remain in the filtered supernatants. Direct contact between Salmonella and BMDCs is required. We are currently attempting to identify the bacterial components responsible for this effect.

The potential for Type B T-cell activation to lead to auto-immune disease is established [12]. Infection of the gastrointestinal tract with Salmonella, as well as Yersinia, Campylobacter and Shigella [34], is frequently associated with reactive arthritis in humans [35] and mice [36]. Salmonella infection in humans caused incidence rates of between 6 and 30% (with variable severity), reflecting the propensity of different Salmonella species to induce arthritis. The enhanced activation of Type B T cells observed with Salmonella infection is not limited to pathogen-specific T cells as the antigens used in these experiments were not derived from Salmonella. Therefore, it is possible that infected DCs in vivo may incidentally present self-peptide-associated Type B conformers, leading to activation of potentially autoreactive Type B T cells. Processes such as inflammation may increase the supply of exogenous peptide and thereby facilitate the generation of Type B pMHC-II conformers. In fact, several immune cell types, including neutrophils [37] and DCs [38, 39], are known to generate exogenous antigenic peptides. In Type 1 diabetes, related mechanisms are thought to generate peptides from the insulin B chain, which when presented on MHC-II are specifically recognised by diabetogenic Type B T cells, leading to disease [12].

This study is the first to show that exposure of BMDCs to Salmonella enhances the presentation of exogenously supplied peptides to Type B T cells. It suggests a mechanism by which Salmonella infection could lead to a breakdown in immunological tolerance. Further studies will be required to identify the factor responsible for this alteration in peptide presentation and to evaluate the role of Type B T cells in infection and autoimmunity.

Materials and methods

Antibodies

Antibodies were from Thermo Scientific: rabbit anti-mouse IgG-Fc RPE; Dako: rabbit anti-mouse Igs/HRP; BD Transduction Laboratories: mouse anti-human AP-50 (611350), mouse anti-human clathrin heavy chain (610499); Sigma: mouse anti-human β-actin (AC-74); eBioscience: anti-mouse CD11c PE-Cy5 (N418), anti-mouse I-Ed/k PE (14.4.4s); GeneTex: anti-mouse I-Ak R-PE (OX-6). The anti-HLA-DR antibody was from clone L243 and is specific for peptide-loaded HLA-DR.

Plasmid constructs

pCMV8.91, pMD-G and pHRSin-cPPT-SGW lentiviral constructs were provided by Paul Lehner (Cambridge, UK). The HLA-DR3 sequences [15] were cloned into the BamHI and NotI sites of pHRSin-cPPT-SGW after eGFP was excised.

Cell culture, lentiviral transduction and siRNA transfection

HEK293-T, MelJuSo, RAW264.7-CIITA, HeLa and HeLa-CIITA cells were maintained in DMEM, 10% FCS. 3A9 and 11A10 T-cell hybridomas were maintained in DMEM, 5% FCS. Monocyte-derived macrophages and serum were prepared from PBMCs isolated from Buffy Coats (British National Transfusion Service) using Lymphoprep (Axis-Shield). Serum was filtered and heat-inactivated. Monocytes were differentiated into macrophages for 7 days in RPMI-1640 (Sigma), 3% autologous serum, 50 ng/mL M-CSF (Peprotech). For lentivirus production, HEK293-T cells were transfected with pCMV8.91, pMD-G and pHRSin-cPPT-SGW using polyethylenimine (Sigma Aldrich, UK) [40]. After 48 h, lentivirus-containing supernatants were filtered (0.2 μm) and applied to HeLa cells. Transduced cells were sorted using a MoFlo flow cytometer (Cytomation). For siRNA transfection, HeLa were seeded in 6-well plates and transfected with siRNA oligonucleotides using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen). Cells were reseeded at 48 h post-transfection before a second transfection with the same oligonucleotide. siRNA oligonucleotides for AP-2 and clathrin heavy chain were from Qiagen [15].

BMDC preparation and antigen presentation

Mice were maintained according to institutional guidelines at the University of Cambridge. BM was harvested from femurs/tibias of 8–12 week female C3H/HeNCrl mice (Charles River) and passed through a 70 μm strainer in IMDM. BM cells were seeded in 9 cm plates at 1 × 106 cells/mL in IMDM, 10% FCS, 2 mM Ultraglutamine (Lonza), 10 ng/mL IL-4 (Peprotech), 20 ng/mL GM-CSF (Peprotech) and penicillin/streptomycin (PAA Laboratories) for ∼30 min to adhere macrophage-precursors. Non-adherent BM cells were reseeded in 6-well plates for the differentiation into BMDCs, with media/cytokine replacement on days 3 and 5. Day 7 BMDCs were harvested by gentle scraping on ice. Differentiated BMDCs were routinely 50–60% CD11c/CD11b+, CD80hi, CD86lo and MHC-IIlo, as assessed by flow cytometry. For antigen presentation, BMDCs were seeded at 3 × 104 cells/well in 96-well-flat-bottomed plates more than 6 h prior to Salmonella infection. For sorts, DCs were seeded at 5 × 106 cells/9 cm plate prior to infection. At 20 h post-infection, cells were washed with PBS, then antigen (HEL protein (Sigma) or HEL46–51 peptide (Cambridge Bioscience)) and T cells were added. T-cell hybridomas were pre-washed with DMEM, 5% FCS and were added at a 5:1 T cell:DC ratio (refer to Supporting Information Fig. 3 for titration). Culture supernatants were harvested after 24 h, frozen at −80 °C and then IL-2 quantified by ELISA using mouse IL-2 Ready-SET-Go! kits (eBioscience).

Salmonella strains, infection and flow cytometry

Salmonella Typhimurium 12023 (ATCC) WT and ΔssaV strains that constitutively express GFP from pFVP25.1 were grown as described previously [15]. MelJuSo, RAW264.7-CIITA and HeLa cells were infected by SPI1-invasion as described previously [15]. BMDCs and monocyte-derived macrophage were infected with stationary phase Salmonella (pre-opsonised in 20% normal mouse serum (PAA Laboratories) or autologous human serum, respectively, for 30 min) for 60 min at a MOI of 10:1. Where specified, Salmonella were HK at 65°C for 45 min prior to opsonisation. For flow cytometry, cells were harvested by scraping and incubated with appropriate antibodies, in FACS buffer (PBS, 5% FCS) at 4°C. BMDCs were incubated with Mouse Fc Block (BD Biosciences) for 5 min at 4°C prior to antibody addition. After washing, cells were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde and analysed using an FACScan Flow Cytometer and Summit software (BD Biosciences). MHC-II surface expression was calculated as mean fluorescence of infected cells (GFP positive)/mean fluorescence of uninfected cells (GFP negative) ×100.

Western blot

Cells were harvested using Cell Dissociation Buffer (Sigma) and lysed for 30 min at 4°C in PBS, 1% Nonidet P-40 substitute, 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Diagnostics), and 5 mM Iodoacetamide. Samples were boiled in SDS-PAGE loading buffer before protein separation by SDS-PAGE and transfer to Immobilon-P PVDF membrane (Millipore). Membranes were probed with antibodies and analysed by rapid immuno-detection using ECL. Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk powder/0.05% Tween-20 for subsequent detections.

Cryo-immunoelectron microscopy

MelJuSo cells were infected with GFP-Salmonella in 9 cm plates. At 12 h post-infection, cells were washed and surface HLA-DR was labelled (L243 antibody) at 4°C. After 20 min, cells were washed and returned to 37°C. After 0 and 7 h endocytosis, cells were fixed in 0.2% glutaraldehyde/2% paraformaldehyde for 2 h at RT. Fixed cells were harvested, embedded in gelatin, and cryo-sectioned using a Leica FCS [41]. Ultrathin sections (50 nm) were cut at –120°C using a Cryo-immuno knife (Diatome, Switzerland) and cells were labelled with 10 nm Protein A gold particles (Cell Biology, Medical School, Utrecht University) in PBS/1% BSA. Images were collected using a Philips/FEI CM10 electron microscope.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Prism where p = 0.01 – 0.05 (*), p = 0.001–0.01 (**) and p < 0.001 (***) was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Royal Society of New Zealand Rutherford Foundation with additional support from the Wellcome Trust and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre. We thank Dr. Emil Unanue (Washington, USA) for providing the 3A9 and 11A10 T-cell hybridomas, Paul Lehner (Cambridge, UK) for the pCMV8.91, pMD-G and pHRSin-cPPT-SGW lentiviral constructs, Karin de Punder and Nicole van der Wel for assistance with cryo-immunoelectron microscopy, Nigel Miller for FACS sorting, and Sarah Gibbs, Stephen Newland and Paola Zaccone for assistance with BMDC preparation.

Glossary

- BMDC

bone marrow-derived dendritic cell

- HEL

hen egg lysozyme

- HK

heat-killed

- Ii

invariant chain

- MVB

multi-vesicular body

- pMHC-II

peptide-MHC-II

- SCV

Salmonella-containing vacuole

- SPI

Salmonella pathogenicity island

- S. Typhimurium

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium

- T3SS

Type III secretion system

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no financial or commercial conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re-organized for online delivery, but are not copy-edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Figure 1: Representative gating strategies for MelJuSo, HeLa-CIITA and BMDCs (A) and flow cytometry plots showing representative MHC-II down-regulation by Salmonella for each HeLa-HLA-DR3 transfectant used in Figure 2 (B)

Figure 2: Salmonella does not down-regulate MHC-II in human monocyte-derived macrophage or a murine macrophage cell line (RAW264.7-CIITA)

Figure 3: Relationship between BMDC: T hybridoma cell ratio and IL-2 response

Figure 4: Transwell experiment showing exposure to Salmonella is sufficient to enhance presentation of exogenous peptide to Type B T cells

References

- 1.Brumell JH, Grinstein S. Salmonella redirects phagosomal maturation. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2004;7:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broz P, Ohlson MB, Monack DM. Innate immune response to Salmonella typhimurium, a model enteric pathogen. Gut. Microbes. 2012;3:62–70. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rescigno M, Urbano M, Valzasina B, Francolini M, Rotta G, Bonasio R, Granucci F, et al. Dendritic cells express tight junction proteins and penetrate gut epithelial monolayers to sample bacteria. Nat. Immunol. 2001;2:361–367. doi: 10.1038/86373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuhle V, Hensel M. Cellular microbiology of intracellular Salmonella enterica: functions of the type III secretion system encoded by Salmonella pathogenicity island 2. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2004;61:2812–2826. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4248-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dham SK, Thompson RA. Humoral and cell-mediated immune responses in chronic typhoid carriers. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1982;50:34–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamb CA, Cresswell P. Assembly and transport properties of invariant chain trimers and HLADR-invariant chain complexes. J. Immunol. 1992;148:3478–3482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCormick PJ, Martina JA, Bonifacino JS. Involvement of clathrin and AP-2 in the trafficking of MHC class II molecules to antigen-processing compartments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:7910–7915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502206102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakke O, Dobberstein B. MHC class II-associated invariant chain contains a sorting signal for endosomal compartments. Cell. 1990;63:707–716. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90137-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cresswell P. Assembly, transport, and function of MHC class II molecules. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1994;12:259–293. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Niel G, Wubbolts R, Ten Broeke T, Buschow SI, Ossendorp FA, Melief CJ, Raposo G, et al. Dendritic cells regulate exposure of MHC class II at their plasma membrane by oligoubiquitination. Immunity. 2006;25:885–894. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lovitch SB, Unanue ER. Conformational isomers of a peptide-class II major histocompatibility complex. Immunol. Rev. 2005;207:293–313. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohan JF, Levisetti MG, Calderon B, Herzog JW, Petzold SJ, Unanue ER. Unique autoreactive T cells recognize insulin peptides generated within the islets of Langerhans in autoimmune diabetes. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:350–354. doi: 10.1038/ni.1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peterson DA, DiPaolo RJ, Kanagawa O, Unanue ER. Quantitative analysis of the T-cell repertoire that escapes negative selection. Immunity. 1999;11:453–462. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheminay C, Mohlenbrink A, Hensel M. Intracellular Salmonella inhibit antigen presentation by dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2005;174:2892–2899. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lapaque N, Hutchinson JL, Jones DC, Meresse S, Holden DW, Trowsdale J, Kelly AP. Salmonella regulates polyubiquitination and surface expression of MHC class II antigens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:14052–14057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906735106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Velden AW, Copass MK, Starnbach MN. Salmonella inhibit T-cell proliferation by a direct, contact-dependent immunosuppressive effect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:17769–17774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504382102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bueno SM, Riquelme S, Riedel CA, Kalergis AM. Mechanisms used by virulent Salmonella to impair dendritic cell function and evade adaptive immunity. Immunology. 2012;137::28–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2012.03614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McSorley SJ, Asch S, Costalonga M, Reinhardt RL, Jenkins MK. Tracking Salmonella-specific CD4 T cells in vivo reveals a local mucosal response to a disseminated infection. Immunity. 2002;16:365–377. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salazar-Gonzalez RM, Niess JH, Zammit DJ, Ravindran R, Srinivasan A, Maxwell JR, Stoklasek T, et al. CCR6-mediated dendritic cell activation of pathogen-specific T cells in Peyer's patches. Immunity. 2006;24:623–632. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yrlid U, Svensson M, Hakansson A, Chambers BJ, Ljunggren HG, Wick MJ. In vivo activation of dendritic cells and T cells during Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:5726–5735. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5726-5735.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flores-Langarica A, Marshall JL, Bobat S, Mohr E, Hitchcock J, Ross EA, Coughlan RE, et al. T-zone localized monocyte-derived dendritic cells promote Th1 priming to Salmonella. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011;41:2654–2665. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell EK, Mastroeni P, Kelly AP, Trowsdale J. Inhibition of cell surface MHC class II expression by Salmonella. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004;34:2559–2567. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wubbolts R, Neefjes J. Intracellular transport and peptide loading of MHC class II molecules: regulation by chaperones and motors. Immunol. Rev. 1999;172:189–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walseng E, Bakke O, Roche PA. Major histocompatibility complex class II-peptide complexes internalize using a clathrin- and dynamin-independent endocytosis pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:14717–14727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801070200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inaba K, Turley S, Iyoda T, Yamaide F, Shimoyama S, Reis e Sousa C, Germain RN, et al. The formation of immunogenic major histocompatibility complex class II-peptide ligands in lysosomal compartments of dendritic cells is regulated by inflammatory stimuli. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:927–936. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mellman I, Turley SJ, Steinman RM. Antigen processing for amateurs and professionals. Trends Cell. Biol. 1998;8:231–237. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iwasaki A, Kelsall BL. Localization of distinct Peyer's patch dendritic cell subsets and their recruitment by chemokines macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-3alpha, MIP-3beta, and secondary lymphoid organ chemokine. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:1381–1394. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.8.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tobar JA, Carreno LJ, Bueno SM, Gonzalez PA, Mora JE, Quezada SA, Kalergis AM. Virulent Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium evades adaptive immunity by preventing dendritic cells from activating T cells. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:6438–6448. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00063-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sachse M, Urbe S, Oorschot V, Strous GJ, Klumperman J. Bilayered clathrin coats on endosomal vacuoles are involved in protein sorting toward lysosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:1313–1328. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-10-0525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Purdy GE, Russell DG. Ubiquitin trafficking to the lysosome: keeping the house tidy and getting rid of unwanted guests. Autophagy. 2007;3:399–401. doi: 10.4161/auto.4272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strong BS, Unanue ER. Presentation of Type B Peptide-MHC complexes from hen egg white lysozyme by TLR ligands and Type I IFNs independent of H2-DM regulation. J. Immunol. 2011;187:2193–2201. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lovitch SB, Esparza TJ, Schweitzer G, Herzog J, Unanue ER. Activation of type B T cells after protein immunization reveals novel pathways of in vivo presentation of peptides. J. Immunol. 2007;178:122–133. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mattsby-Baltzer I, Lindgren K, Lindholm B, Edebo L. Endotoxin shedding by enterobacteria: free and cell-bound endotoxin differ in Limulus activity. Infect. Immun. 1991;59:689–695. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.2.689-695.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hill Gaston JS, Lillicrap MS. Arthritis associated with enteric infection. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2003;17:219–239. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6942(02)00104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arnedo-Pena A, Beltran-Fabregat J, Vila-Pastor B, Tirado-Balaguer MD, Herrero-Carot C, Bellido-Blasco JB, Romeu-Garcia MA, et al. Reactive arthritis and other musculoskeletal sequelae following an outbreak of Salmonella hadar in Castellon, Spain. J. Rheumatol. 2010;37:1735–1742. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.091250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noto Llana M, Sarnacki SH, Giacomodonato MN, Caccuri RL, Blanco GA, Cerquetti MC. Sublethal infection with Salmonella enteritidis by the natural route induces intestinal and joint inflammation in mice. Microbes. Infect. 2009;11:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Potter NS, Harding CV. Neutrophils process exogenous bacteria via an alternate class I MHC processing pathway for presentation of peptides to T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 2001;167:2538–2546. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Accapezzato D, Nisini R, Paroli M, Bruno G, Bonino F, Houghton M, Barnaba V. Generation of an MHC class II-restricted T-cell epitope by extracellular processing of hepatitis delta antigen. J. Immunol. 1998;160:5262–5266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santambrogio L, Sato AK, Carven GJ, Belyanskaya SL, Strominger JL, Stern LJ. Extracellular antigen processing and presentation by immature dendritic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:15056–15061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ehrhardt C, Schmolke M, Matzke A, Knoblauch A, Will C, Wixler V, Ludwig S. Polyethylenimine, a cost-effective transfection reagent. Signal Transduction. 2006;6:179–184. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peters PJ, Pierson J. Immunogold labeling of thawed cryosections. Methods Cell Biol. 2008;88:131–149. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)00408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.