Abstract

A pathological increase in the late component of the cardiac Na+ current, INaL, has been linked to disease manifestation in inherited and acquired cardiac diseases including the long QT variant 3 (LQT3) syndrome and heart failure. Disruption in INaL leads to action potential prolongation, disruption of normal cellular repolarization, development of arrhythmia triggers, and propensity to ventricular arrhythmia. Attempts to treat arrhythmogenic sequelae from inherited and acquired syndromes pharmacologically with common Na+ channel blockers (e.g. flecainide, lidocaine, and amiodarone) have been largely unsuccessful. This is due to drug toxicity and the failure of most current drugs to discriminate between the peak current component, chiefly responsible for single cell excitability and propagation in coupled tissue, and the late component (INaL) of the Na+ current. Although small in magnitude as compared to the peak Na+ current (~1 – 3%), INaL alters action potential properties and increases Na+ loading in cardiac cells. With the increasing recognition that multiple cardiac pathological conditions share phenotypic manifestations of INaL upregulation, there has been renewed interest in specific pharmacological inhibition of INa. The novel antianginal agent ranolazine, which shows a marked selectivity for late versus peak Na+ current, may represent a novel drug archetype for targeted reduction of INaL. This article aims to review common pathophysiological mechanisms leading to enhanced INaL in LQT3 and heart failure as prototypical disease conditions. Also reviewed are promising therapeutic strategies tailored to alter the molecular mechanisms underlying INa mediated arrhythmia triggers.

INTRODUCTION

The cardiac action potential arises from a delicate balance of depolarization and repolarization orchestrated through precisely timed opening and closing of ion channels. Na+ channel activation produces an influx of Na+ that causes membrane depolarization. Membrane excitation then leads to rapid voltage dependent inactivation of Na+ channels and nearly complete “turning off” of the current. A transient, or peak Na current (INaT) is observed and is chiefly responsible for the rapid action potential upstroke and, in coupled tissue, propagation of the action potential (AP). A second component of Na+ current that persists throughout the duration of the action potential has also been identified, and because it occurs subsequent to the large transient peak current, is termed late INa (INaL). While INaL is miniscule compared to peak INaT (INaL < 1% of INaT [1]), it occurs throughout the low conductance phase of the action potential and thus contributes to action potential morphology, plateau potentials, and AP duration in human ventricular myocytes [2, 3] and Na+ buildup in cardiac cells. Even though the magnitude of INaL is low, its persistence throughout the duration of the action potential results in net Na+ loading comparable to that via INaT [1, 4].

It has recently been demonstrated that in some pathological settings INaL is upregulated, which may disrupt the repolarization phase of the action potential and lead to the development of arrhythmia triggers. Here, we review the latest findings on common pathophysiological mechanisms leading to an enhanced late INa, in the setting of congenital long QT3 syndrome and the acquired QT prolongation in heart failure. New strategies for therapeutic intervention directed at INaL will also be discussed. A historical perspective and other aspects related to the topic of the INaL have also recently been reviewed in [5, 6].

BRIEF REVIEW OF THE CARDIAC ACTION POTENTIAL WAVEFORM

Multiple distinct action potential morphologies exist, depending on myocardial location. Ventricular cells exhibit the “classical” action potential morphology with 5 discrete phases. Phase 0 is the rapid depolarizing phase that results when Na+ channels activate and an influx of Na+ causes the membrane potential to depolarize. Phase 1 corresponds to the “notch” marked by inactivation of Na+ channels and outward movement of K+ ions through transient outward current (Ito). In phase 2, a low conductance plateau phase, inward and outward ion movements are balanced mainly by L-type Ca2+ channels and delayed rectifier K+ channels, respectively. Phase 3 marks the final repolarization phase of the action potential, which occurs due to inactivation of Ca2+ currents and continued K+ efflux, allowing the cell to return to its resting potential (phase 4).

STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF THE VOLTAGE GATED CARDIAC SODIUM CHANNEL

The human cardiac voltage-gated sodium channel (NaV1.5) is a macromolecular complex consisting of α and β subunits and accessory proteins [8, 9]. The α subunit, encoded by SCN5A, is composed of four heterologous domains (DI – DIV) each with six transmembrane segments (S1-S6) [8, 10]. Ion selectivity and permeation is controlled by the P loop between S5 – S6. Concerted movement of the positively charged S4 segments “activate” the channel in response to a transmembrane voltage depolarization [11, 12]. Channel inactivation occurs on three discrete timescales: fast inactivation within milliseconds, intermediate inactivation within 100 ms [13] and slow inactivation on the order of seconds [14]. Critical for fast inactivation is the hydrophobic isoleucine-phenylalanine-methionine (IFM) motif located on the intracellular linker between DIII and DIV [8, 11]. The COOH terminal has also been implicated in NaV1.5 inactivation [2, 15, 16].

Gain of function mutations in SCN5A can result in variant 3 of the congenital long QT3 syndrome (LQT3) [8, 17, 18]. The long QT phenotype arising from LQT3 mutations generally results from a failure of inactivation of the Na+ channel, which results in persistent inward Na+ current (an increase in INaL) throughout the duration of the action potential. Increased INaL leads to prolongation of the action potential duration at the level of the cell, which manifests as QT-interval prolongation on the ECG.

In addition to the α subunit, the Na+ channel is modulated by multiple accessory subunits. With respect to INaL, coexpression of the α with the β1 (but not β2) subunit slows INaL decay kinetics, dramatically increases INaL relative to the maximum peak current (2.3% vs 0.48%), and produces a rightward shift in the steady-state availability curve [19]. Additionally in the heart failure setting, NaV1.5 is downregulated with no change in β1 expression, suggesting further β1 subunit enhanced INaL in heart failure [2, 20]. Recently, Mishra et al. has shown opposite effects of β1 and β2 in normal and heart failure models of canine hearts, with β1-siRNA post-transcriptional silencing reducing INaL density and accelerating decay, whereas β2-siRNA produces just the opposite [21].

The first β subunit (SCN4B – β4) mutation was described [22] in a 21-month old girl that had a QTc of 712 ms and intermittent 2:1 heart block. Coexpression with the α-subunit revealed a small (3.42 mV), but significant positive shift in the steady-state availability curve, leading to an increased window current (described in more detail below). At -60 mV, the expression of SCN5A with mutant β4 caused an 8-fold increase in INaL compared with SCN5A alone [22]. Mutations in all four β subunits have since been reported and causally linked to multiple arrhythmogenic phenotypes [23].

DERANGED CHANNEL FUNCTION CAN CAUSE LATE INa

At least three distinct alterations in NaV1.5 gating have been shown to increase in INaL including window currents, differential gating modalities, and nonequilibrium gating. These mechanisms are described below in the context of naturally occurring mutations, which generally led to their discovery. However, it is now clear that the gating properties of Na+ channels can be altered by physiological modulators such as Ca2+, calmodulin and phosphorylation, both in the context of normal physiology and in pathological conditions (discussed later and listed in Table 3).

Table 3.

Pathological and experimental conditions associated with an enhanced INaL (reproduced from [6])

| Congenital clinical conditions | |

|

| |

| LQT3 syndrome (Na+ channel mutations) | [52] |

| LQT-CAV3 (caveolin-3 mutations) | [62] |

| LQT-SCN4B (β4-subunit mutations) | [22] |

|

| |

| Acquired clinical conditions | |

|

| |

| Heart failure | [26, 48, 76] |

| Post-MI myocardial remodeling | [77] |

|

| |

| Experimental conditions | |

|

| |

| Second messengers (CaM and CaMKIIδ) | [68, 78] |

| Oxygen free radicals | [79-82] |

| INaL enhancing agents | [83-87] |

| Acute hypoxia | [88-90] |

| Ischemic metabolites | [82, 91-94] |

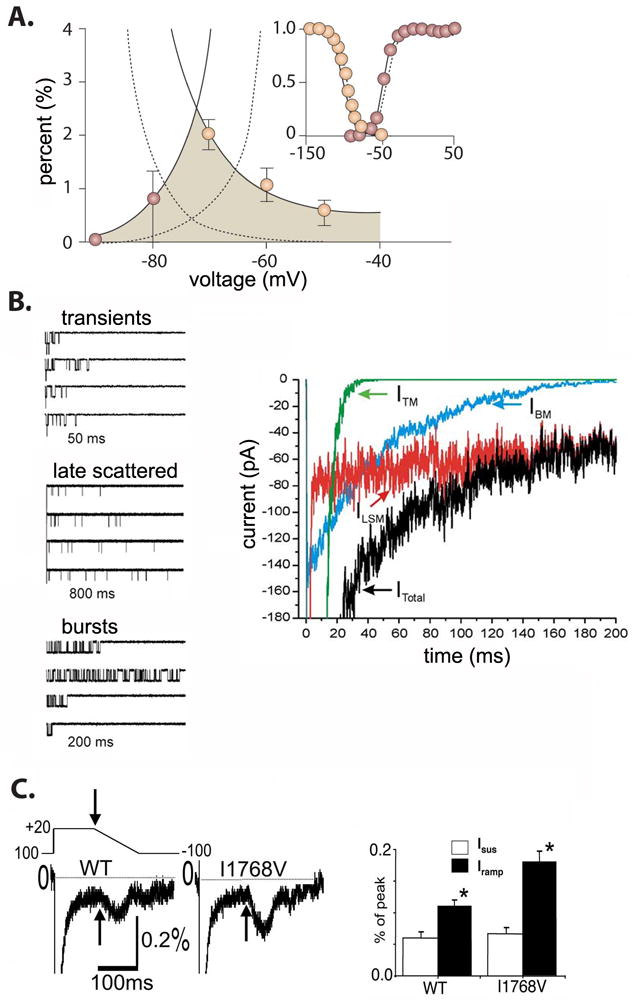

Window currents and INaL

For cardiac Na+ channels, there exists a voltage range where the steady state inactivation curve and activation curve overlap. Within this voltage regime, during repolarization of the cardiac AP, channels that have previously inactivated may reactive, or in the experimental setting, if the membrane is held at constant voltage, a steady-state equilibrium current ensues [6, 24, 25]. In the ventricular myocardium, voltages within the region of overlap between activation and inactivation occur subsequent to late repolarization (phase 3) and reactivation is not favorable. Conditions that slow repolarization, increase recovery from inactivation, or increase the width of the window can lead to enhanced reactivation of Na+ channels and propensity to early afterdepolarizations and triggered activity [24]. Although window current is not appreciable in wild-type human [26] and guinea pig [27] ventricular myocytes, at least three LQT3 mutations, L619F, N1325S and R1644H have been shown to increase window current and, presumably, to cause the disease phenotype [28] [29]. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. Mechanisms of late INa.

A) Schematic of an increased window current (shaded region) in the LQT3 linked N1325S. The dotted lines represent the wild-type. Note the minimal overlap between steady-state inactivation and the activation curve normally exists outside the voltage range of repolarization. Adapted from [8]. B) Modal gating of INaL. A simulation demonstrating three modes (left panels) of gating, transients, late scattered, and bursts comprise the total INa current (right panel) (simulation time course is shown). Adapted from [1]. C) Non-equilibrium gating of I1768V. A schematic of a negative ramp protocol. Persistent current was measured at the end of a 100ms depolarizing pulse (arrow) and was not significantly different between wild-type and the I1768V mutation. Ramp currents were measured as the peak inward current during the negative ramp protocol and were significantly larger in the mutant Na+ channel (summary data in bar graph on right). Adapted from [38].

Differential gating modes of NaV1.5 produce INaL

In addition to window currents, burst mode gating of NaV1.5 is another mechanism producing INaL. It was once thought that a “non-window” INaL was carried by a separate isoform of the cardiac Na+ channel; however, it is now clear that INaL and INaT share molecular identity [30] since Maltsev and Undrovinas recorded INaL from heterologously expressed NaV1.5 in the absence of other isoforms [1].

Using midmyocardial ventricular myocytes, Maltsev and Undrovinas separated the Na+ current into three phases: early (transient), intermediate, and late, and recorded three distinct gating modalities: transients, bursts, and late scattered openings. The earliest phase of Na+ current decay (<40 ms) involved all three modes of gating, while the intermediate phase (40 – 300 ms) only involved late scattered openings and bursts, with an inverse relationship between extent of depolarization and bursting. Finally an ultra late decay (>300 ms) involved only the late scattered mode. Of note, these recordings were made at room temperature [2].

Clancy et al. observed infrequent transitions from normally inactivating Na channels to bursting channels in recordings from heterologously expressed single NaV1.5 sodium channels. These data were analyzed to determine “rates” into the burst mode of gating. The dwell time in the burst mode allowed an estimate of the rate of exit from the mode. A computational model based on these rates was then used to predict the magnitude of INaL expected from ensemble currents. These predictions were finally validated experimentally, suggesting that burst mode gating in NaV1.5 underlies INaL [31].

Studies in canine ventricular myocytes have shown that the magnitude of the burst mode is pacing frequency dependent, with a decrease in INaL during rapid heart rates [32]. Rate dependence of INaL was also shown for human channels in heterologously expressed channels, where INaL was larger in magnitude at slow frequencies [31]. These data suggest a plausible explanation for bradycardia-linked arrhythmia events commonly observed in LQT3 [33].

The pharmacology of INaL is similar to NaV1.5, with blockade by STX and TTX exhibiting a single site binding with affinities typical of NaV1.5 [26, 34], and sensitivity to Cd2+ (typical for cardiac but not neuronal Na+ channel isoforms) [2, 35]. Lastly, silencing by siRNA of SCN5A decreases INaL by 75%, significantly reducing APD and variability in canine heart failure models [36]. Thus, evidence suggests that NaV1.5 is likely a major determinant of INaL in both normal and failing ventricular myocytes [2, 30].

Undrovinas and Maltsev [2] have summarized the major biophysical and pharmacological characteristics of physiological INaL as follows: 1) slow, voltage-independent inactivation and reactivation at room temperature (~0.5 s); 2) steady-state activation and inactivation similar to INaT; 3) low sensitivity to TTX and STX, comparable to NaV1.5; and 4) the existence of an INaL with similar biophysical properties in dogs, guinea pigs, rabbits, and rats (see Table 2) [2]. Their results importantly suggest that the multi-modal composition of the INa current may allow for pharmacological targeting by gating mode specific modulation [1]

Table 2.

Cardiac cell types physiologically expressing INaL (reproduced from [6])

Importantly, INaL is not a background Na+ current (INaB), which is TTX insensitive and shows no voltage dependence [37]. To date, INaB remains poorly characterized and has an unclear molecular identity [2].

Nonequilibrium gating produces INaL

An additional mechanism that can produce INaL during action potential repolarization was deemed “non-equilibrium” gating because INaL was not observed during experiments measuring steady-state or equilibrium current characteristics. As shown in Figure 1C, an LQT3 linked mutation I1768V did not alter INaL measured at the end of a prolonged depolarizing pulse compared to wild-type current amplitude. However, in response to a negative ramp current, a transient inward current twice the amplitude of wild-type current was observed. A computational analysis predicted that an increase in the rate of recovery from inactivation was a plausible explanation for the observed experimental results. The model predictions suggest that faster recovery from inactivation allowed sufficient INaL during a high resistance phase of action potential repolarization, at voltages favoring channel activation, so that the AP is prolonged, consistent with the phenotype. Thus, although measurement of INaL is negligible under steady-state voltage conditions, protocols that simulate repolarization reveal INaL current amplitudes similar to other LQT3 mutations [38].

CELL TYPE SPECIFICITY OF INaL

Nearly all cardiac myocytes express a late component of INa (see Table 2). However, expression is not uniform; in studies of canine ventricular myocytes, INaL density was found to be 47% greater in M cells, as compared to endocardial and epicardial cells, with no difference in frequency dependence and recovery from inactivation [32]. However, this result may be species dependent; Noble et al. found just the opposite in guinea pig myocytes: the smallest INaL current density was observed in midmyocardial regions [27]. Other potential explanations for this discrepancy include M cells comprising only a small population of the midmyocardial layer, and the absence of M cells in particular species (e.g. guinea pig, rat, and pig) [4, 39-41]. Although INaL has been found in ventricular myocytes of humans [1, 26, 34], it will be especially important to determine the distribution of INaL density, since transmural heterogeneity of INaL current density is suggested as a plausible source of pathologic APD heterogeneity leading to ventricular tachyarrhythmias such as torsades de pointes [32, 42]. Rabbit atrial cells have INaL with similar current density to ventricular myocytes [43] but Purkinje fibers have increased INaL compared to ventricular cells [44, 45].

DISEASES AND CONDITIONS ASSOCIATED WITH INaL

As shown in Table 3, there are multiple mechanisms of action underlying enhanced pathologic INaL, which can be separated into congenital, acquired, and experimentally induced conditions that mimic physiological conditions. This review will focus on LQT3 as the prototypical congenital mutation, and heart failure and its antecedent processes as the prototypical acquired disease leading to enhanced INaL.

Congenital disorders

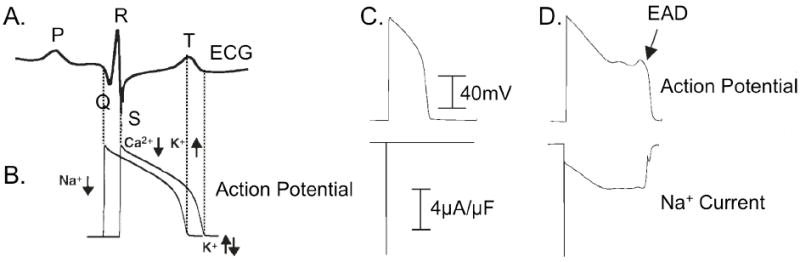

Of the congenital conditions associated with INaL, LQT3 syndrome has been most widely studied and characterized. The link between late Na+ current and congenital arrhythmias began when Bennett et al. described the first LQT3 mutation, ΔKPQ [52], which results from a 3 amino acid deletion (lysine, proline, glutamine at positions 1505 - 1507) in the linker region between domains III and IV [52]. ΔKPQ causes a transient failure of fast inactivation of the Na+ channel, which results in a small population of channels fluctuating between a normal “dispersed” mode, and a “burst” mode of gating [52, 53]. The persistent Na+ current induced by the bursting mode causes an increase in the action potential duration that manifests as QT prolongation on the body surface ECG (see Figure 2A and 2B).

Figure 2. Electrical gradients within the myocardium detected on the ECG, and action potential prolongation via mutation induced late INa.

A. and B. Schematic representation of the relationship between an action potential and the ECG detected as spatial and temporal gradients for one cardiac cycle. The P wave represents atrial depolarization, the QRS complex represents ventricular activation, and the T wave represents the gradient of ventricular repolarization. Dotted lines indicate the link between deflections on the ECG and underlying cellular level electrical events. B. Schematic of the cellular electrical activity underlying the ECG. C and D: Simulated action potential (top) and INa (bottom) for wild-type (C) and ΔKPQ (D). In the wild-type, Na+ channels activate, followed quickly by inactivation; ΔKPQ mutant channels fail to inactivate and cause a small, persistent (<5% peak) Na+ current (panel D, bottom) that prolongs the action potential and can lead to arrhythmogenic early afterdepolarizations (EADs) shown in the top panel of D. Note, in both C and D bottom panels, peak INa is off scale. Figure adapted from [59, 60].

Importantly, not all LQT3 mutations produce INaL via noninactivating bursting channels; as discussed, I1768V [38] via non-equilibrium gating, the D1790G mutation by PKA induced bursting [54], increased window currents as seen with N1325S and R1644H [29], and S1103Y, a mutation implicated in sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) which causes a pH-dependent increase in INaL [55]. The reader is referred to [8] for a detailed review of Na+ channel mutations and arrhythmia.

Independent of mechanism, LQT3 mutations promote a delay in ventricular repolarization during plateau potentials. This can promote a substrate for triggered activity via early afterdepolarizations (EADs), which result from reactivation of L-type Ca2+ channels [56-58] (during phase 2 of the action potential). It is important to note that the enhanced late Na+ current is not necessarily the charge carrier of the EAD, but merely sets up conditions favorable for a normally functioning L-type Ca2+ channel to reactivate. It has been suggested that these EADs lead to triggered activity and propensity to polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and torsades de pointes [8], the primary arrhythmia mechanism and cause of sudden cardiac death in LQT3 carriers [10].

Other congenital clinical conditions associated with an enhanced INaL result from mutations in proteins that either interact with NaV1.5 directly as part of a macromolecular complex [61], or are important for cellular localization. For example, sequence analysis of the gene encoding caveolin-3, a major scaffolding protein present in the caveolae of the heart, revealed 4 novel mutations in CAV3-encoded caveolin-3 from patients referred for LQTS genetic testing. In each of these mutations, expression of mutant caveolin-3 with NaV1.5 resulted in a 2 – 3 fold increase in INaL compared with wild-type caveolin-3 [62]. This study also confirmed colocalization of NaV1.5 with caveolin-3, suggesting that mutations in proteins within the macromolecular complex containing NaV1.5 can disrupt normal Na+ channel function and lead to a persistent INaL. Cronk et al. have also reported CAV3 mutations implicated in LQT associated SIDS [63].

Other studies have implicated mutations in SNTA1, the gene encoding α1-syntrophin, and associated with the SIDS disease entity, as a novel regulator of NaV1.5 function. These mutations lead to release of neuronal nitric oxide synthase by the plasma membrane Ca-ATPase PMC4Ab, causing an increase in both peak and late Na current [64, 65].

Calcium signaling mediated increase in INaL

Ca2+ modulation of the Na+ channel has also been demonstrated after direct binding sites for Ca2+ [66] and the Ca2+ binding protein calmodulin (CaM) [67] were found on the carboxy terminus of the Na+ channel. These discoveries led to studies that revealed inactivation of INaT can be modulated by Ca2+, CaM, and/or the Ca2+ / CaM / CaM-kinase signaling cascade [2]. While the Ca2+ / CaM / CaM-kinase signaling cascade and interaction with the Na+ channel is complex, and not fully elucidated, a few studies, in particular with CaMKII have revealed interesting interactions with Na+ channels [68, 69].

In studies examining the interaction of the Na+ channel and INaL with CaMKII, it was found that CaMKII coimmunoprecipitates and phosphorylates Na+ channels [68]. Overexpression of CaMKIIδC in rabbit myocytes (acute) and transgenic mice (chronic) led to (1) enhanced INaL, (2) slowed fast inactivation (but enhanced intermediate inactivation), (2) slowed recovery from inactivation, (3) shifted steady state availability in hyperpolarizing direction that was Ca2+-dependent, and (4) a rise in intracellular Na [2, 68]; importantly, these results were reversible with CaMKII inhibition (acute only). Interestingly, Bers and Grandi [70] note the striking similarity of these CaMKII-induced changes with the LQT3- and Brugada-linked mutant 1795insD [71]. Maltsev and Undrovinas [69] found that in both normal and failing canine ventricular myocytes, that INaL was enhanced by direct Ca2+ binding, CaM interactions and by CaMKII signaling. All three mechanisms were shown to cause increased INaL and Na influx by slowing inactivation kinetics, observed as a positive shift in the steady state availability curve [2, 69]. Evidence of CaMKII upregulation has also been confirmed in other studies examining the effects of CaMKII in the heart failure setting [72-74]. These data point to the potential for novel therapeutic targeting of Ca2+-dependent modulation of INaL to prevent calcium loading that likely underlies arrhythmia propensity in pathological remodeling.

Acquired disorders: A role for late Na current in arrhythmogenesis in heart failure

Late Na+ current and increased intracellular Na+ have been shown to play a crucial role in arrhythmias associated with acquired diseases such as heart failure and post MI remodeling, due to their impact on action potential duration and repolarization abnormalities. Approximately 40% of chronic heart failure patients die due to sudden cardiac death, with ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation documented in 80% of patients with ECG Holter monitoring at the time of death [2, 95, 96].

The first evidence for the potential role for INaL in arrhythmogenesis derived from experiments of rat ventricular myocytes in the absence and presence of hypoxia. INaL increased during hypoxia 2 – 4-fold (from 50-100 pA during normoxia to 180 – 205 pA during hypoxia), and was suggested to give rise to early afterdepolarizations (EADs) and arrhythmias during hypoxic states [4, 88, 97]. Later, the importance of INaL in heart failure was found through experiments that acted to normalize pathologic INaL; this “rescue” resulted in 1) normalization of repolarization; 2) decrease in beat-to-beat APD variability; and 3) improvement in Ca2+ handling and contractility [2, 48, 98, 99]. Because hypoxia, ischemia and overt heart failure represent a continuum of global oxygen deprivation and subsequent disease, the general mechanisms leading to these derangements will be discussed together.

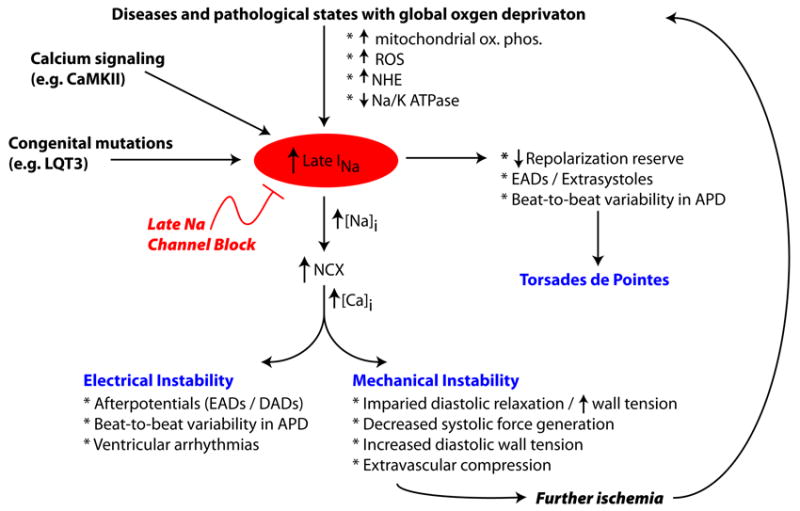

Under various “oxygen deprivation” insults (hypoxia, ischemia, reactive oxygen species, and heart failure), intracellular Na+ quickly rises due both to deranged ion homeostasis (both Na+ and Ca2+) as well as altered Na+ channel gating [100], leading to an increased INaL.

Failure of ion homeostasis begins with an influx of Na+ through the Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE) [101] in attempt to raise the acidified pH (through the extrusion of H+) due to ischemia. For example, under conditions of hypoxia, NHE from rabbit ventricular myocytes stimulated at 1 Hz accounted for 39% of the total Na+ influx (as compared to 5% during normoxia) [102]. Inhibition of the NHE during ischemic episodes attenuated the rise in intracellular Na+ [103, 104].

Along with Na+ influx via the NHE, a parallel decrease in energy production due to mitochondrial dysfunction and loss of ATP results in reduced Na+ elimination through the Na+/K+ ATPase [105], which further augments intracellular Na+.

A direct consequence of intracellular Na+ overload is an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ accumulation. Intracellular Na+ accumulation causes the Na+/Ca2+ (NCX) exchanger to work in reverse-mode (3 Na+ ions extruded for 1 Ca2+ influxed). Pharmacological and antisense inhibition of NCX greatly reduce the rise in Ca2+ [106, 107]. Entry of Ca2+ into the myocyte via the NCX (as well as the L-type Ca2+ channel) ultimately exceeds Ca2+ efflux and precipitates Ca2+ overload. Deranged Ca2+ homeostasis leads to spontaneous SR Ca2+ release, a pathological version of the Ca2+-induced-Ca2+ release process [4, 108], resulting in beat-to-beat variability in repolarization with cellular repolarization abnormalities (e.g. EADs and delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs)) and triggered arrhythmias [105]. Propensity for triggered arrhythmias via APD prolongation, dispersion of repolarization, and EADs and DADs, have all been described in patients with heart failure [2, 109]. In addition to repolarization abnormalities and electrical instability from deranged accumulation and cycling of Ca2+, the ventricular myocardium is predisposed to mechanical instability including impaired diastolic relaxation, contractile dysfunction, and microcirculatory resistance [100].

At the cellular level, failing (but not normal) canine ventricular myocytes that exhibited prolonged APs, Ca2+ transients and substantial diastolic Ca2+ accumulation leading to spontaneous Ca2+ release were rescued by addition of TTX and ranolazine (a selective INaL blocker) [110-112]. The improved function in canine ventricular myocytes [110] is further evidence linking INaL to the induction of deranged Ca+ homeostasis at the cellular level. A subsequent study using human ventricular myocytes [26] similarly found a normalization of APD and abolishment of EADs with the addition of TTX.

Intrinsic gating abnormalities of the cardiac Na+ channel, in addition to ion homeostatic dysfunction has also been linked to conditions of heart failure. Maltsev and Undrovinas first reported the existence of a novel, ultraslow inactivating Na current, INaL, in both normal and failing human hearts [26], and recently have shown that chronic heart failure leads an increased density and slower inactivation kinetics of INaL [34] as compared to normal hearts, with a 53.6% increase in total Na+ influx in failing myocytes. Single channel analysis reveals that the two modes of gating comprising the late INa, late scattered mode and burst mode of gating, are significantly slower in failing human ventricular myocytes compared to normal ventricular myocytes and heterologously expressed NaV1.5 [1]. Importantly, there were no differences in the unitary conductance of late Na+ current between normal and failing human hearts, further suggesting that enhanced late current appears to be generated by a single population of channels that are upregulated in HF [113].

As shown in Figure 3, conditions and diseases that lead to an increased late INa exhibit electrical instability (due to afterdepolarizations, beat-to-beat variability in repolarization, ventricular arrhythmias), mechanical instability (impaired diastolic relaxation and ventricular wall tension, increased diastolic and decreased systolic force generation), as well as mitochondrial dysfunction [42]. This cascade leads to further ischemia and abnormal contraction, setting up a pathological feedback loop.

Figure 3. Cascade of INaL induced dysfunction.

Congenital and acquired conditions exhbit an increased late Na+ current, which can both cause electrical and mechanical instability. Blocking INaL, may effectively blunt the cascade of INaL induced cardiac dysfunction. See text for details. Figure adapted from [42, 105].

PHARMACOLOGY OF INaL

Pharmacological enhancement of late INa

There are various compounds that can increase late INa including veratridine [114], peptide toxins (e.g. ATX-II, AP-A, AP-Q, β-pompilidotoxin) [115], pyrethroids [116-118], and small molecules (BDF9148, DPI201106) [6, 83, 84, 117]. Zaza et al. notes that although these compounds serve as important experimental tools, interpretation of their results must be with caution as their varied mechanisms of action producing late INa will impact the severity of repolarization abnormality and proarrhythmic potential [6].

For example, there have been numerous recent studies using ATX-II as a pharmacological model of LQT3 syndrome [111, 119-122] to probe antiarrhythmic efficacy of ranolazine. As the mechanism of ATX-II on NaV1.5 is thought primarily to destabilize inactivation [85], this model may only be useful for some LQT3 linked mutations, but not others (e.g. I1768V [38], D1790G [123]). Furthermore, mutations might alter the affinity of Na+ channels for certain drugs (e.g. affinity of wild-type Na+ channels with ATX-II for ranolazine ~6 μM [124] vs. ΔKPQ Na+ channel ~ 12 μM [125] for ranolazine), making interpretation of pharmacokinetics (e.g. potency ratios between INaL and IKr) difficult.

Pharmacological suppression of late INa

In the late 1980’s, after decades of research into Class I Na+ channel blockers, the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST), a randomized placebo controlled study to assess the efficacy of Na+ channel blockade, commenced. CAST compared three common antiarrhythmics, flecainide, encainide, and moricizine, for antiarrhythmic efficacy after myocardial infarction. The trial was abruptly and prematurely terminated when it was found that flecainide and encainide paradoxically increased mortality by 2 – 3x (relative risk 3.6) as compared to placebo [126, 127]. Because of this stunning failure, Na+ channel blockade had fallen out of favor therapeutically, in part, because of the inability of current drugs to selectively discriminate between the peak and late components of INa. Revival of Na+ channel targeting has been a result of a new understanding of the emergent effects of Na+ channel drug blockade, diseases and conditions with selective increase in INaL (such as LQT3 and heart failure), as well as newer drugs that selectively target INaL, as discussed next.

Nonselective Na channel blockers

As INaL is presumably the same channel as INaT [2, 26, 34-36, 113, 128], classical Na+ channel blockers (flecainide, lidocaine, quinidine, mexilitine, TTX, STX, Cd2+ etc.), as well as those with off-target Na+ channel blocking effects (e.g. amiodarone) are effective at suppressing INaL [6]. To date, selective blockade of the late component of the Na+ current, without concomitant blockade of the peak Na+ current (responsible for maintaining cellular upstroke velocity and propagation in coupled tissue) has been elusive (see Table 4). For example, flecainide, a prototypical Class IC Na+ channel blocker only displays 2.9 – 5-fold INaL/INaT selectivity, with potential toxicity owing to potent INaT blockade, which can set up conditions of conduction block and reentrant ventricular tachyarrhythmias [127, 129]; this was likely a major determinant of the arrhythmias observed during the CAST trial.

Table 4.

Comparison of block potency ratios for common Na+ channel blockers (adapted from [6])

| Agent | INaL / INaT | INaL/ IKr | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amiodarone | 13 | ≤1.5 | [128, 131] |

| Flecainide | 2.9 – 5 | <0.1 – 2 | [132-135] |

| Ranolazine | 9 – 38 | 1.5 – 2 | [98, 125] |

| Lidocaine | 2.7* | - | [98] |

INaL / IKr ratios are approximate, because complete concentration-response curves are not available for all agents and within the same experimental setting.

Reference to unpublished data in [98]

Amiodarone, a mixed ion channel blocker, was shown to have a 13-fold of selectivity of INaL/INaT (6.7μM vs 87 μM), with virtually no effect on INaT in the therapeutic range in studies of midmyocardial ventricular myocytes from failing human hearts. Amiodarone shifted steady-state inactivation curve and accelerated the decay time constant in a dose dependent manner, suggesting preferential blockade of inactivated and activated states [128]. While these data suggest a promising therapeutic strategy for patients with heart failure, chronic amiodarone therapy carries an extensive adverse effect profile including pulmonary fibrosis, hepatotoxicity, thyrotoxicity, marked QT prolongation and bradycardia, among the most serious [130].

Finally, both flecainide and amiodarone exhibit potent off-target effects, and in particular show virtually no selectivity between INaL and IKr, a key repolarizing current, that if blocked, could further increase action potential prolongation and destabilize repolarization.

Because of these limitations, current research is aimed at developing selective INaL inhibitors with minimal off target and toxic side effects.

Selective Late Na+ channel blockers

It was first reported in the 1970’s that INaL was more sensitive to TTX than INaT, demonstrating selective targeting of each component of the Na+ current [136, 137]. More recently, it was shown that a partial inhibition of INaL (~50%) with TTX acted to normalize APD and abolish arrhythmogenic EADs in ventricular myocytes from failing hearts [26, 34]. There has also been considerable recent interest in a novel antianginal agent, ranolazine, with distinct efficacy against INaL.

Ranolazine: The first selective INaL Na+ channel blocker

Ranolazine is a piperazine derivative, structurally similar to lidocaine, that exhibits minimal effects on hemodynamics such as heart rate and blood pressure [17]. Approved in 2006 by the FDA for the treatment of chronic angina pectoris, it is the only FDA-approved drug that specifically blocks the late component of the Na+ current. While the precise mechanism of ranolazine is unknown, it has been an effective antianginal and anti-ischemic agent ostensibly by reducing Ca2+ overload through inhibition of lNaL [138], inhibiting reverse mode of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger [42].

Mutational analysis suggests that ranolazine shares the common local anesthetic binding site, with mutation of F1760A in ΔKPQ mutant Na+ channels reducing potencies of both ranolazine and lidocaine [125]. Ranolazine is also more potent than lidocaine for ΔKPQ; taken together, this implies a common receptor, but differential state-dependent binding affinity between ranolazine and lidocaine [6, 125].

In addition to potent, selective INaL inhibition (6 μM vs 294 μM peak INa) [98, 124] ranolazine blocks multiple ion channels, but importantly blocks the repolarizing hERG current IKr with therapeutic concentrations (1 – 10 μM) [139]. The result is a mild concentration dependent QTc prolongation seen in patients with chronic stable angina [140]. Of note, ranolazine showed no increased proarrhythmic potential, and may even reduce the incidence of ischemia related arrhythmias [138]. Lastly, ranolazine is a very weak inhibitor of the L-type Ca2+ channel (IC50 = 296 μM) and the NCX (IC50 = 91 μM) [124], indicating that within the therapeutic regime, ranolazine primarily acts on INaL and IKr, with minimal to no effects on ICaL, INa/Ca or the NHE, important contributors to Na+ and Ca2+ homeostasis [42].

Ranolazine for the treatment of ischemia, hypoxia, and heart failure

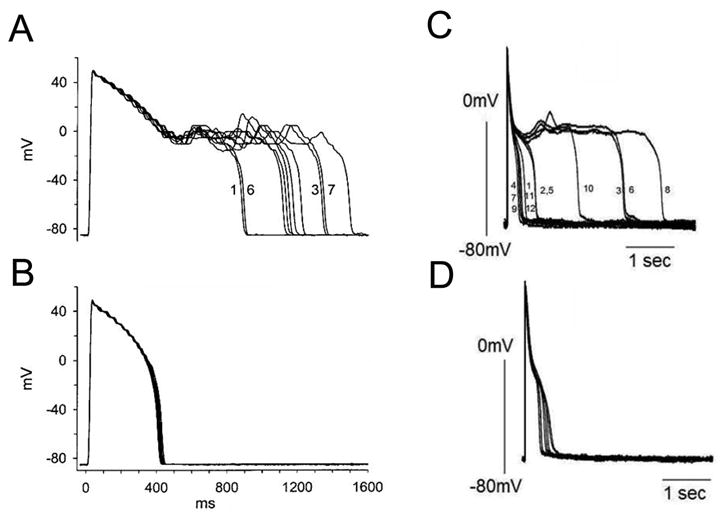

Many large clinical trials have already proven the utility of ranolazine for the treatment of cardiac ischemia, hypoxia, and heart failure [141, 142]. As discussed, these conditions share the commonalities of an increased INaL, and deranged ion homeostasis with Na+ overload preceding Ca2+ overload. Selective blockade of INaL by ranolazine thus diminishes INaL and the consequent Ca2+ overload induced by reverse mode NCX. Clinically, this decreases diastolic wall tension, and extravascular compression allowing enhanced perfusion to ischemic myocardium [138]. Importantly, the cardioprotective effects of ranolazine occur at a concentration that has minimal effects on heart rate, coronary blood flow and systemic arterial blood pressure [143, 144], making ranolazine unique among other antianginal agents currently in use. Reduction of APD variability has also been elegantly shown in a study of canine heart failure treated with ranolazine [98]. See Figure 4.

Figure 4. Pharmacological targeting of INaL normalizes APs in a pharmacological model of LQT3 and in heart failure.

(A) Superimposed recordings of 10 consecutive action potentials from a guinea pig myocyte in the presence of 10nM ATX-II, and (B) in the presence of 10nM ATX-II and 10 μM ranolazine. Modified from [121]. (C) Ranolazine (RAN) reduces APD variability in left ventricular myocytes isolated from canine failing hearts. (A) Twelve consecutive APs recorded at a pacing rate of 0.25 Hz are superimposed. (B) APs recorded in the presence of 10 μM ranolazine. From [98].

Ranolazine for the treatment of LQT3

Although the QT prolongation observed with therapeutic ranolazine has resulted in a contraindication for patients on other QT prolonging drugs and those with preexisting QT prolongation [145], ranolazine’s strong selectivity for INaL might prove beneficial in specific patient populations, such as those with LQT3. Numerous in vitro [120, 121, 124, 125, 146] and in vivo [146-148] studies suggest that through preferential reduction of INaL (9 – 38x) [124], ranolazine, appears effective in attenuating action potential duration (APD) prolongation and suppressing the development of EADs. See Figure 4.

Many studies assessing ranolazine for the treatment of LQT3 syndrome have utilized pharmacological models of LQT3 via the addition of ATXII to induce a persistent Na+ current [111, 119-121]. Because the affinity of ΔKPQ mutant Na+ channels for ranolazine is 2-fold lower than WT Na+ channels (12 μM vs. 6 μM) [124, 125], and is equivalent to the IKr affinity (12 μM) [124, 139], these studies must be interpreted with caution, as these similar affinities might render ranolazine proarrhythmic in this specific patient population.

Clinical assessment of ranolazine has been carried out in one study of 5 carriers of the LQT3-ΔKPQ mutation, where Moss et al. found a modest reduction of QTc (~4%) with ~5 μM peak ranolazine infusion [146]. Importantly, ranolazine had minimal effects on upstroke velocity (phase 0) of the action potential [146, 149, 150]. However, there was a nonsignificant, but unexplained rebound increase in repolarization parameters (QT, QTc, QTpeak, Tpeak – Tend, and Tduration) 16 hours after ranolazine infusion. While this, in addition to the small sample size of this study and intravenous administration of the drug necessitates further clinical validation, this study highlights the proof-of-principle that selective targeting of pathologically induced late INa represents a tractable therapeutic target for this, and other disease linked mutations arising from enhanced INaL.

Although promising, ranolazine is marred by its potent inhibition of IKr, a key repolarizing current, and its consequent potential to prolong QT interval. In terms of treatment of syndromes arising from overabundance of late Na+ current, it has yet to be conclusively demonstrated which effect will predominate – therapeutic block of late Na+ current, or pathological suppression of IKr. The answer may lie in consideration of combined effects of ranolazine and its many metabolites. Clinical pharmacokinetic studies of ranolazine suggests extensive metabolism via CYP3A mediated pathways of biotransformation [151]. Four predominant metabolites were identified at plasma concentrations 30 – 40% of the parent compound, all of which produce a substantially weaker inhibition of IKr (40 – 50% inhibition at 50 μM). IC50 values for an additional 7 metabolites tested were all >50 μM [138]. Importantly, all 11 metabolites potently inhibited INaL by 12 – 57% at 10 μM [138].

Thus, a higher INaL/IKr selectivity may explain ranolazine’s safety and efficacy. Nonetheless, future work should focus on ranolazine analogues with greater selective targeting of INaL; this could prove most beneficial in diseases such as the LQT3 syndrome. Additional studies should also address the safety and efficacy in this specific patient population; although the study by Moss et al. [146] showed moderate benefit with ranolazine and LQT3-ΔKPQ carriers, this study was small (5 patients), and of limited duration (~24 hours). Future studies should also address whether ranolazine is merely effective at normalizing surrogate markers of arrhythmia (e.g. normalization of the QTc interval), or is actually effective at preventing LQT associated rhythm sequences, such as short-long-short sequences, and pause-induced arrhythmia [152].

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

A wealth of experimental evidence suggests that a number of clinical conditions may result from the common pathway of deranged late Na+ current. This realization has led to renewed interest in pharmacological targeting of Na+ current as a therapeutic strategy. The ideal therapeutic is one that specifically targets late current, without affecting peak current, since attenuation of the latter is chiefly responsible for proarrhythmia associated with Na+ channel blocking drugs [4, 129].

To date, ranolazine is the only FDA-approved drug that specifically blocks INaL, with 9 – 38 fold selectivity over INaT. It has been safe and effective in reducing myocardial ischemia, and symptomatic angina [138]. The MERLIN study [153] also demonstrated a reduction in both tachy- and bradyarrhythmias within the first week of treatment.

With respect to acquired conditions such as heart failure, this review focused on pharmacological targeting of the Na+ channel, but other ion channels (e.g. Ca2+ channels), pumps, and exchangers represent equally plausible drug targets to reduce intracellular Na+, Ca2+ overload, and cardiac dysfunction [42].

Table 1.

Major membrane currents underlying a typical ventricular action potential (adapted from [7])

| Membrane Currents | Description | Gene (α-subunit) | Contribution to action potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inward ionic currents | |||

| INa | Na+ current | SCN5A (NaV1.5) | Initial depolarization of the action potential |

| ICa,L | L-type Ca2+ current | CACNA1C (CaV1.2), CACNA1D (CaV1.3) | Maintains plateau phase of action potential |

| Outward ionic currents | |||

| Ito | Ca2+-independent transient outward K+ current | KCND2 (KV4.2), KCND3 (KV4.3), KCNA4 (KV1.4) | Responsible for early repolarization |

| IKr, IKs | Rapid and slow delayed K+ rectifier currents | KCNH2 (KV11.1), KCNQ1 (KV7.1) | Aids repolarization during plateau |

| ISS, IKs,Low | Slow inactivating K+ currents | KCN1B (KV2.1), KCNA5 (KV1.5) | Aids late repolarization |

| IK1 | Inward rectifier K+ current | KCNJ2 (Kir2.1), KCNJ12 (Kir2.2) | Late repolarization, helps establish Vrest |

| Other ionic currents | |||

| INaCa | Na+ - Ca2+ exchanger | SLC8A1 (NCX1), SLC8A2 (NCX2) | Late depolarization |

| INaK | Na+ - K+ pump | ATP1A1, 2, 3 | Late repolarization |

Highlights.

INaL can disrupt cellular repolarization and increase propensity to ventricular arrhythmia.

Although small compared to peak Na+ current, INaL increases Na+ loading in cardiac cells.

Multiple cardiac pathological conditions share phenotypic manifestations of INaL upregulation.

Specific pharmacological inhibition of INa is desired

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- ATX-II

Anemonia sulcata toxin

- AP-A,Q

Anthopleurin A, Q

- hERG

Human Ether-a-go-go Related Gene, KV11.1

- INaT

Transient (T) Na+ current

- INaL

Late (L) Na+ current

- LQT(3)

Long QT syndrome (variant 3)

- STX

Saxitoxin

- TTX

Tetrodotoxin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Maltsev VA, Undrovinas AI. A multi-modal composition of the late Na+ current in human ventricular cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69(1):116–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Undrovinas A, V, Maltsev A. Late sodium current is a new therapeutic target to improve contractility and rhythm in failing heart. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2008;6(4):348–59. doi: 10.2174/187152508785909447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coraboeuf E, Deroubaix E, Coulombe A. Effect of tetrodotoxin on action potentials of the conducting system in the dog heart. Am J Physiol. 1979;236(4):H561–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.236.4.H561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noble D, Noble PJ. Late sodium current in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease: consequences of sodium-calcium overload. Heart. 2006;92(Suppl 4):iv1–iv5. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.078782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maltsev VA, Undrovinas A. Late sodium current in failing heart: friend or foe? Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;96(1-3):421–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zaza A, Belardinelli L, Shryock JC. Pathophysiology and pharmacology of the cardiac “late sodium current.”. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;119(3):326–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demir SS. Computational modeling of cardiac ventricular action potentials in rat and mouse: review. Jpn J Physiol. 2004:523–30. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.54.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruan Y, Liu N, Priori SG. Sodium channel mutations and arrhythmias. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009:337–48. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abriel H, Kass RS. Regulation of the voltage-gated cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5 by interacting proteins. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15(1):35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clancy CE, Kass RS. Inherited and acquired vulnerability to ventricular arrhythmias: cardiac Na+ and K+ channels. Physiol Rev. 2005;85(1):33–47. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00005.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balser JR. The cardiac sodium channel: gating function and molecular pharmacology. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33(4):599–613. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balser JR. Structure and function of the cardiac sodium channels. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42(2):327–38. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang DW, Makita N, Kitabatake A, Balser JR, George AL., Jr Enhanced Na(+) channel intermediate inactivation in Brugada syndrome. Circ Res. 2000;87(8):E37–43. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.8.e37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartmann HA, Tiedeman AA, Chen SF, Brown AM, Kirsch GE. Effects of III-IV linker mutations on human heart Na+ channel inactivation gating. Circ Res. 1994;75(1):114–22. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cormier JW, Rivolta I, Tateyama M, Yang AS, Kass RS. Secondary structure of the human cardiac Na+ channel C terminus: evidence for a role of helical structures in modulation of channel inactivation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(11):9233–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110204200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Motoike HK, Liu H, Glaaser IW, Yang AS, Tateyama M, Kass RS. The Na+ channel inactivation gate is a molecular complex: a novel role of the COOH-terminal domain. J Gen Physiol. 2004;123(2):155–65. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doshi D, Morrow JP. Potential application of late sodium current blockade in the treatment of heart failure and atrial fibrillation. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2009;10(Suppl 1):S46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Darbar D, Kannankeril PJ, Donahue BS, Kucera G, Stubblefield T, Haines JL, et al. Cardiac sodium channel (SCN5A) variants associated with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2008;117(15):1927–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.757955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maltsev VA, Kyle JW, Undrovinas A. Late Na+ current produced by human cardiac Na+ channel isoform Nav1.5 is modulated by its beta1 subunit. J Physiol Sci. 2009;59(3):217–25. doi: 10.1007/s12576-009-0029-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zicha S, Maltsev VA, Nattel S, Sabbah HN, Undrovinas AI. Post-transcriptional alterations in the expression of cardiac Na+ channel subunits in chronic heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;37(1):91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mishra S, Undrovinas NA, Maltsev VA, Reznikov V, Sabbah HN, Undrovinas A. Post-Transcriptional Silencing of SCN1B and SCN2B Genes Modulates Late Sodium Current in Cardiac Myocytes from Normal Dogs and Dogs with Chronic Heart Failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00948.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medeiros-Domingo A, Kaku T, Tester DJ, Iturralde-Torres P, Itty A, Ye B, et al. SCN4B-encoded sodium channel beta4 subunit in congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2007;116(2):134–42. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.659086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilde AA, Brugada R. Phenotypical manifestations of mutations in the genes encoding subunits of the cardiac sodium channel. Circ Res. 2011;108(7):884–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.238469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeng J, Rudy Y. Early afterdepolarizations in cardiac myocytes: mechanism and rate dependence. Biophys J. 1995;68(3):949–64. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80271-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.January CT, Riddle JM. Early afterdepolarizations: mechanism of induction and block. A role for L-type Ca2+ current. Circ Res. 1989;64(5):977–90. doi: 10.1161/01.res.64.5.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maltsev VA, Sabbah HN, Higgins RS, Silverman N, Lesch M, Undrovinas AI. Novel, ultraslow inactivating sodium current in human ventricular cardiomyocytes. Circulation. 1998;98(23):2545–52. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.23.2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakmann BF, Spindler AJ, Bryant SM, Linz KW, Noble D. Distribution of a persistent sodium current across the ventricular wall in guinea pigs. Circ Res. 2000;87(10):910–4. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.10.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wehrens XH, Rossenbacker T, Jongbloed RJ, Gewillig M, Heidbuchel H, Doevendans PA, et al. A novel mutation L619F in the cardiac Na+ channel SCN5A associated with long-QT syndrome (LQT3): a role for the I-II linker in inactivation gating. Hum Mutat. 2003;21(5):552. doi: 10.1002/humu.9136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang DW, Yazawa K, George AL, Jr, Bennett PB. Characterization of human cardiac Na+ channel mutations in the congenital long QT syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(23):13200–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maltsev VA, Kyle JW, Mishra S, Undrovinas A. Molecular identity of the late sodium current in adult dog cardiomyocytes identified by Nav1.5 antisense inhibition. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295(2):H667–76. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00111.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clancy CE, Tateyama M, Kass RS. Insights into the molecular mechanisms of bradycardia-triggered arrhythmias in long QT-3 syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(9):1251–62. doi: 10.1172/JCI15928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zygmunt AC, Eddlestone GT, Thomas GP, Nesterenko VV, Antzelevitch C. Larger late sodium conductance in M cells contributes to electrical heterogeneity in canine ventricle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281(2):H689–97. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.2.H689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nemec J, Buncova M, Bulkova V, Hejlik J, Winter B, Shen WK, et al. Heart rate dependence of the QT interval duration: differences among congenital long QT syndrome subtypes. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2004;15(5):550–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2004.03096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maltsev VA, Silverman N, Sabbah HN, Undrovinas AI. Chronic heart failure slows late sodium current in human and canine ventricular myocytes: implications for repolarization variability. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9(3):219–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Satin J, Kyle JW, Chen M, Bell P, Cribbs LL, Fozzard HA, et al. A mutant of TTX-resistant cardiac sodium channels with TTX-sensitive properties. Science. 1992;256(5060):1202–5. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5060.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Undrovinas A, Mishra S, Undrovinas N. Silencing of SCN5A gene by siRNA descrease late sodium current and action potential duration in ventricular cardiomyocytes from dogs with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2005;112(II-127) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spindler AJ, Noble SJ, Noble D, LeGuennec JY. The effects of sodium substitution on currents determining the resting potential in guinea-pig ventricular cells. Exp Physiol. 1998;83(2):121–36. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1998.sp004096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clancy CE, Tateyama M, Liu H, Wehrens XH, Kass RS. Non-equilibrium gating in cardiac Na+ channels: an original mechanism of arrhythmia. Circulation. 2003;107(17):2233–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000069273.51375.BD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bryant SM, Shipsey SJ, Hart G. Regional differences in electrical and mechanical properties of myocytes from guinea-pig hearts with mild left ventricular hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;35(2):315–23. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shipsey SJ, Bryant SM, Hart G. Effects of hypertrophy on regional action potential characteristics in the rat left ventricle: a cellular basis for T-wave inversion? Circulation. 1997;96(6):2061–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.6.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodriguez-Sinovas A, Cinca J, Tapias A, Armadans L, Tresanchez M, Soler-Soler J. Lack of evidence of M-cells in porcine left ventricular myocardium. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;33(2):307–13. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(96)00205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Belardinelli L, Shryock JC, Fraser H. Inhibition of the late sodium current as a potential cardioprotective principle: effects of the late sodium current inhibitor ranolazine. Heart. 2006;92(Suppl 4):iv6–iv14. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.078790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Persson F, Andersson B, Duker G, Jacobson I, Carlsson L. Functional effects of the late sodium current inhibition by AZD7009 and lidocaine in rabbit isolated atrial and ventricular tissue and Purkinje fibre. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;558(1-3):133–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gintant GA, Datyner NB, Cohen IS. Slow inactivation of a tetrodotoxin-sensitive current in canine cardiac Purkinje fibers. Biophys J. 1984;45(3):509–12. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84187-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vassalle M, Bocchi L, Du F. A slowly inactivating sodium current (INa2) in the plateau range in canine cardiac Purkinje single cells. Exp Physiol. 2007;92(1):161–73. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2006.035279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Le Grand B, Coulombe A, John GW. Late sodium current inhibition in human isolated cardiomyocytes by R 56865. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1998;31(5):800–4. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199805000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wasserstrom JA, Salata JJ. Basis for tetrodotoxin and lidocaine effects on action potentials in dog ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1988;254(6 Pt 2):H1157–66. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.254.6.H1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Undrovinas AI, Maltsev VA, Sabbah HN. Repolarization abnormalities in cardiomyocytes of dogs with chronic heart failure: role of sustained inward current. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55(3):494–505. doi: 10.1007/s000180050306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zilberter Yu I, Starmer CF, Starobin J, Grant AO. Late Na channels in cardiac cells: the physiological role of background Na channels. Biophys J. 1994;67(1):153–60. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80464-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Conforti L, Tohse N, Sperelakis N. Tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium current in rat fetal ventricular myocytes--contribution to the plateau phase of action potential. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1993;25(2):159–73. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1993.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baruscotti M, DiFrancesco D, Robinson RB. Na(+) current contribution to the diastolic depolarization in newborn rabbit SA node cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279(5):H2303–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.5.H2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bennett PB, Yazawa K, Makita N, George AL. Molecular mechanism for an inherited cardiac arrhythmia. Nature. 1995:683–5. doi: 10.1038/376683a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clancy CE, Rudy Y. Linking a genetic defect to its cellular phenotype in a cardiac arrhythmia. Nature. 1999;400(6744):566–9. doi: 10.1038/23034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tateyama M, Rivolta I, Clancy CE, Kass RS. Modulation of cardiac sodium channel gating by protein kinase A can be altered by disease-linked mutation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(47):46718–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308977200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Plant LD, Bowers PN, Liu Q, Morgan T, Zhang T, State MW, et al. A common cardiac sodium channel variant associated with sudden infant death in African Americans, SCN5A S1103Y. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(2):430–5. doi: 10.1172/JCI25618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thomas G, Gurung IS, Killeen MJ, Hakim P, Goddard CA, Mahaut-Smith MP, et al. Effects of L-type Ca2+ channel antagonism on ventricular arrhythmogenesis in murine hearts containing a modification in the Scn5a gene modelling human long QT syndrome 3. J Physiol (Lond) 2007:85–97. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.121921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Viswanathan PC, Rudy Y. Pause induced early afterdepolarizations in the long QT syndrome: a simulation study. Cardiovasc Res. 1999:530–42. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lankipalli RS, Zhu T, Guo D, Yan GX. Mechanisms underlying arrhythmogenesis in long QT syndrome. Journal of electrocardiology. 2005:69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clancy CE, Kass RS. Defective cardiac ion channels: from mutations to clinical syndromes. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(8):1075–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI16945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clancy CE, Kass R. Inherited and acquired vulnerability to ventricular arrhythmias: cardiac Na+ and K+ channels. Physiol Rev. 2005:33–47. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00005.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meadows LS, Isom LL. Sodium channels as macromolecular complexes: implications for inherited arrhythmia syndromes. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67(3):448–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vatta M, Ackerman MJ, Ye B, Makielski JC, Ughanze EE, Taylor EW, Tester DJ, et al. Mutant caveolin-3 induces persistent late sodium current and is associated with long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2006;114(20):2104–12. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.635268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cronk LB, Ye B, Kaku T, Tester DJ, Vatta M, Makielski JC, et al. Novel mechanism for sudden infant death syndrome: persistent late sodium current secondary to mutations in caveolin-3. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4(2):161–6. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ueda K, Valdivia C, Medeiros-Domingo A, Tester DJ, Vatta M, Farrugia G, et al. Syntrophin mutation associated with long QT syndrome through activation of the nNOS-SCN5A macromolecular complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(27):9355–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801294105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng J, Van Norstrand DW, Medeiros-Domingo A, Valdivia C, Tan BH, Ye B, et al. Alpha1-syntrophin mutations identified in sudden infant death syndrome cause an increase in late cardiac sodium current. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2(6):667–76. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.891440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wingo TL, Shah VN, Anderson ME, Lybrand TP, Chazin WJ, Balser JR. An EF-hand in the sodium channel couples intracellular calcium to cardiac excitability. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11(3):219–25. doi: 10.1038/nsmb737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mori M, Konno T, Ozawa T, Murata M, Imoto K, Nagayama K. Novel interaction of the voltage-dependent sodium channel (VDSC) with calmodulin: does VDSC acquire calmodulin-mediated Ca2+-sensitivity? Biochemistry. 2000;39(6):1316–23. doi: 10.1021/bi9912600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wagner S, Dybkova N, Rasenack EC, Jacobshagen C, Fabritz L, Kirchhof P, et al. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulates cardiac Na+ channels. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(12):3127–38. doi: 10.1172/JCI26620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maltsev VA, Reznikov V, Undrovinas NA, Sabbah HN, Undrovinas A. Modulation of late sodium current by Ca2+, calmodulin, and CaMKII in normal and failing dog cardiomyocytes: similarities and differences. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294(4):H1597–608. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00484.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bers DM, Grandi E. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II regulation of cardiac ion channels. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2009;54(3):180–7. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181a25078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bezzina C, Veldkamp MW, van Den Berg MP, Postma AV, Rook MB, Viersma JW, et al. A single Na(+) channel mutation causing both long-QT and Brugada syndromes. Circ Res. 1999;85(12):1206–13. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.12.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ai X, Curran JW, Shannon TR, Bers DM, Pogwizd SM. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase modulates cardiac ryanodine receptor phosphorylation and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in heart failure. Circ Res. 2005;97(12):1314–22. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000194329.41863.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Currie S, Loughrey CM, Craig MA, Smith GL. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIdelta associates with the ryanodine receptor complex and regulates channel function in rabbit heart. Biochem J. 2004;377(Pt 2):357–66. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kirchhefer U, Schmitz W, Scholz H, Neumann J. Activity of cAMP-dependent protein kinase and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in failing and nonfailing human hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42(1):254–61. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mohler PJ, Schott JJ, Gramolini AO, Dilly KW, Guatimosim S, duBell WH, et al. Ankyrin-B mutation causes type 4 long-QT cardiac arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death. Nature. 2003;421(6923):634–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Valdivia CR, Chu WW, Pu J, Foell JD, Haworth RA, Wolff MR, et al. Increased late sodium current in myocytes from a canine heart failure model and from failing human heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38(3):475–83. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Huang B, El-Sherif T, Gidh-Jain M, Qin D, El-Sherif N. Alterations of sodium channel kinetics and gene expression in the postinfarction remodeled myocardium. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12(2):218–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tan HL, Kupershmidt S, Zhang R, Stepanovic S, Roden DM, et al. A calcium sensor in the sodium channel modulates cardiac excitability. Nature. 2002;415(6870):442–7. doi: 10.1038/415442a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ward CA, Giles WR. Ionic mechanism of the effects of hydrogen peroxide in rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1997;500(Pt 3):631–42. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ahern GP, Hsu SF, Klyachko VA, Jackson MB. Induction of persistent sodium current by exogenous and endogenous nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(37):28810–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003090200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ma JH, Luo AT, Zhang PH. Effect of hydrogen peroxide on persistent sodium current in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2005;26(7):828–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gautier M, Zhang H, Fearon IM. Peroxynitrite formation mediates LPC-induced augmentation of cardiac late sodium currents. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44(2):241–51. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Honerjager P. Cardioactive substances that prolong the open state of sodium channels. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1982;92:1–74. doi: 10.1007/BFb0030502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hoey A, Amos GJ, Ravens U. Comparison of the action potential prolonging and positive inotropic activity of DPI 201-106 and BDF 9148 in human ventricular myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1994;26(8):985–94. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1994.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chahine M, Plante E, Kallen RG. Sea anemone toxin (ATX II) modulation of heart and skeletal muscle sodium channel alpha-subunits expressed in tsA201 cells. J Membr Biol. 1996;152(1):39–48. doi: 10.1007/s002329900083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yuill KH, Convery MK, Dooley PC, Doggrell SA, Hancox JC. Effects of BDF 9198 on action potentials and ionic currents from guinea-pig isolated ventricular myocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130(8):1753–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fu LY, Li Y, Cheng L, Zhou HY, Yao WX, Xia GJ, et al. Effect of sea anemone toxin anthopleurin-Q on sodium current in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2001;22(12):1107–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ju YK, Saint DA, Gage PW. Hypoxia increases persistent sodium current in rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1996;497(Pt 2):337–47. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hammarstrom AK, Gage PW. Hypoxia and persistent sodium current. Eur Biophys J. 2002;31(5):323–30. doi: 10.1007/s00249-002-0218-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fearon IM, Brown ST. Acute and chronic hypoxic regulation of recombinant hNa(v)1.5 alpha subunits. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324(4):1289–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kohlhardt M, Fichtner H, Frobe U. Metabolites of the glycolytic pathway modulate the activity of single cardiac Na+ channels. FASEB J. 1989;3(8):1963–7. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.8.2542113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Burnashev NA, Undrovinas AI, Fleidervish IA, Makielski JC, Rosenshtraukh LV. Modulation of cardiac sodium channel gating by lysophosphatidylcholine. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1991;23(Suppl 1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(91)90020-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Undrovinas AI, Fleidervish IA, Makielski JC. Inward sodium current at resting potentials in single cardiac myocytes induced by the ischemic metabolite lysophosphatidylcholine. Circ Res. 1992;71(5):1231–41. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.5.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wu J, Corr PB. Palmitoyl carnitine modifies sodium currents and induces transient inward current in ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1994;266(3 Pt 2):H1034–46. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.3.H1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bayes de Luna A, Coumel P, Leclercq JF. Ambulatory sudden cardiac death: mechanisms of production of fatal arrhythmia on the basis of data from 157 cases. Am Heart J. 1989;117(1):151–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(89)90670-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nikolic G, Bishop RL, Singh JB. Sudden death recorded during Holter monitoring. Circulation. 1982;66(1):218–25. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.66.1.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Saint DA, Ju YK, Gage PW. A persistent sodium current in rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1992;453:219–31. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Undrovinas AI, Belardinelli L, Undrovinas NA, Sabbah HN. Ranolazine improves abnormal repolarization and contraction in left ventricular myocytes of dogs with heart failure by inhibiting late sodium current. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17(Suppl 1):S169–S177. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Maltsev VA, Sabbah HN, Tanimura M, Lesch M, Goldstein S, Undrovinas AI. Relationship between action potential, contraction-relaxation pattern, and intracellular Ca2+ transient in cardiomyocytes of dogs with chronic heart failure. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1998;54(6):597–605. doi: 10.1007/s000180050187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Maier LS. A novel mechanism for the treatment of angina, arrhythmias, and diastolic dysfunction: inhibition of late I(Na) using ranolazine. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2009;54(4):279–86. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181a1b9e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Eigel BN, Hadley RW. Contribution of the Na(+) channel and Na(+)/H(+) exchanger to the anoxic rise of [Na(+)] in ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(5 Pt 2):H1817–22. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.5.H1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bers DM, Barry WH, Despa S. Intracellular Na+ regulation in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57(4):897–912. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00656-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Baetz D, Bernard M, Pinet C, Tamareille S, Chattou S, El Banani H, Coulombe A, Feuvray D. Different pathways for sodium entry in cardiac cells during ischemia and early reperfusion. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;242(1-2):115–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Avkiran M. Basic biology and pharmacology of the cardiac sarcolemmal sodium/hydrogen exchanger. J Card Surg. 2003;18(Suppl 1):3–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8191.18.s1.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hale SL, Shryock JC, Belardinelli L, Sweeney M, Kloner RA. Late sodium current inhibition as a new cardioprotective approach. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44(6):954–67. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Eigel BN, Hadley RW. Antisense inhibition of Na+/Ca2+ exchange during anoxia/reoxygenation in ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281(5):H2184–90. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.5.H2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Schafer C, Ladilov Y, Inserte J, Schafer M, Haffner S, Garcia-Dorado D, et al. Role of the reverse mode of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in reoxygenation-induced cardiomyocyte injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;51(2):241–50. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fabiato A. Calcium-induced release of calcium from the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Am J Physiol. 1983;245(1):C1–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1983.245.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Surawicz B. Electrophysiologic substrate of torsade de pointes: dispersion of repolarization or early afterdepolarizations? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;141:172–84. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Undrovinas NA, Maltsev VA, Belardinelli L, Sabbah HN, Undrovinas A. Late sodium current contributes to diastolic cell Ca2+ accumulation in chronic heart failure. J Physiol Sci. 2010;60(4):245–57. doi: 10.1007/s12576-010-0092-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wasserstrom JA, Sharma R, O’Toole MJ, Zheng J, Kelly JE, Shryock J, et al. Ranolazine antagonizes the effects of increased late sodium current on intracellular calcium cycling in rat isolated intact heart. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331(2):382–91. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.156471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Antzelevitch C, Burashnikov A, Sicouri S, Belardinelli L. Electrophysiologic basis for the antiarrhythmic actions of ranolazine. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8(8):1281–90. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Undrovinas AI, Maltsev VA, Kyle JW, Silverman N, Sabbah HN. Gating of the late Na+ channel in normal and failing human myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34(11):1477–89. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zong XG, Dugas M, Honerjager P. Relation between veratridine reaction dynamics and macroscopic Na current in single cardiac cells. J Gen Physiol. 1992;99(5):683–97. doi: 10.1085/jgp.99.5.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wang SY, Wang GK. Voltage-gated sodium channels as primary targets of diverse lipid-soluble neurotoxins. Cell Signal. 2003;15(2):151–9. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Spencer CI, Sham JS. Mechanisms underlying the effects of the pyrethroid tefluthrin on action potential duration in isolated rat ventricular myocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315(1):16–23. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.084822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Spencer CI, Yuill KH, Borg JJ, Hancox JC, Kozlowski RZ. Actions of pyrethroid insecticides on sodium currents, action potentials, and contractile rhythm in isolated mammalian ventricular myocytes and perfused hearts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298(3):1067–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Soderlund DM, Clark JM, Sheets LP, Mullin LS, Piccirillo VJ, Sargent D, et al. Mechanisms of pyrethroid neurotoxicity: implications for cumulative risk assessment. Toxicology. 2002;171(1):3–59. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(01)00569-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wu L, Shryock JC, Song Y, Belardinelli L. An increase in late sodium current potentiates the proarrhythmic activities of low-risk QT-prolonging drugs in female rabbit hearts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316(2):718–26. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.094862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wu L, Shryock JC, Song Y, Li Y, Antzelevitch C, Belardinelli L. Antiarrhythmic effects of ranolazine in a guinea pig in vitro model of long-QT syndrome. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310(2):599–605. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.066100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Song Y, Shryock JC, Wu L, Belardinelli L. Antagonism by ranolazine of the pro-arrhythmic effects of increasing late INa in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;44(2):192–9. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200408000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wu J, Cheng L, Lammers WJ, Wu L, Wang X, Shryock JC, et al. Sinus node dysfunction in ATX-II-induced in-vitro murine model of long QT3 syndrome and rescue effect of ranolazine. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;98(2-3):198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Abriel H, Wehrens X, Benhorin J, Kerem B, Kass R. Molecular pharmacology of the sodium channel mutation D1790G linked to the long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2000:921–925. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Antzelevitch C, Belardinelli L, Zygmunt AC, Burashnikov A, Di Diego JM, Fish JM, et al. Electrophysiological effects of ranolazine, a novel antianginal agent with antiarrhythmic properties. Circulation. 2004;110(8):904–10. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000139333.83620.5D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Fredj S, Sampson K, Liu H, Kass R. Molecular basis of ranolazine block of LQT-3 mutant sodium channels: evidence for site of action. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2006:16–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]