Abstract

Combined measurements of water isotopologues of a snow pit at Vostok over the past 60 y reveal a unique signature that cannot be explained only by climatic features as usually done. Comparisons of the data using a general circulation model and a simpler isotopic distillation model reveal a stratospheric signature in the 17O-excess record at Vostok. Our data and theoretical considerations indicate that mass-independent fractionation imprints the isotopic signature of stratospheric water vapor, which may allow for a distinction between stratospheric and tropospheric influences at remote East Antarctic sites.

Keywords: ice core, d-excess, triple oxygen, 17O-anomaly, beryllium-10

Stable water isotopic ratios ( and

and  ) have been used for many years as a proxy for local temperature Ts reconstruction in East Antarctica (1, 2). The link with temperature results from mass-dependent isotopic fractionation of water at each phase transition along the water mass trajectory from the evaporative zone to the polar precipitation site. Two different kinds of mass-dependent fractionation effects lead to the depletion in heavy isotopologues of the water vapor. First, equilibrium fractionation is caused by the lower vapor pressure for the heavy isotopologues compared with the one for the abundant light (H2O) water molecules. Second, kinetic fractionation leads to isotopic fractionation due to different molecular diffusivity constants of the light and heavy water isotopologues (light molecules diffuse faster in air than the heavy ones) (3). The observed spatial slope of

) have been used for many years as a proxy for local temperature Ts reconstruction in East Antarctica (1, 2). The link with temperature results from mass-dependent isotopic fractionation of water at each phase transition along the water mass trajectory from the evaporative zone to the polar precipitation site. Two different kinds of mass-dependent fractionation effects lead to the depletion in heavy isotopologues of the water vapor. First, equilibrium fractionation is caused by the lower vapor pressure for the heavy isotopologues compared with the one for the abundant light (H2O) water molecules. Second, kinetic fractionation leads to isotopic fractionation due to different molecular diffusivity constants of the light and heavy water isotopologues (light molecules diffuse faster in air than the heavy ones) (3). The observed spatial slope of  vs.

vs.  lies between 0.75‰ and 0.8‰ °C−1 [±20% at glacial timescales (4–6)] and builds the basis for past temperature reconstruction from

lies between 0.75‰ and 0.8‰ °C−1 [±20% at glacial timescales (4–6)] and builds the basis for past temperature reconstruction from  in ice cores. It should be noted that this relationship can be associated with larger uncertainties of factor 2 for warmer than present-day climates (7). Biases to a constant temporal

in ice cores. It should be noted that this relationship can be associated with larger uncertainties of factor 2 for warmer than present-day climates (7). Biases to a constant temporal  vs. temperature slope may arise from changes of moisture origin for the polar precipitation, precipitation intermittency at the seasonal or interannual scale, postdeposition effects, and changes of moisture trajectories. Tools exist to quantify such biases. First, the second-order parameters deuterium (d)-excess (8) and 17O-excess (9), defined as

vs. temperature slope may arise from changes of moisture origin for the polar precipitation, precipitation intermittency at the seasonal or interannual scale, postdeposition effects, and changes of moisture trajectories. Tools exist to quantify such biases. First, the second-order parameters deuterium (d)-excess (8) and 17O-excess (9), defined as

and

are significantly imprinted by the climatic conditions (temperature and relative humidity) of the moisture origin. Second, the development of atmospheric general circulation models (AGCM) with implemented water isotopologues and water tagging is a strong added value to test the existence of temporal variations of precipitation intermittency or changes of moisture trajectories. These AGCM simulations reproduce indeed very well the seasonal cycles of all water isotopologues in polar regions (10), even if they still fail to represent polar d-excess variations at the glacial–interglacial transition. This makes the use of simpler water isotopic models [mixed-cloud isotopic model (MCIM) (11)] of distillation paths also useful to interpret the d-excess and 17O-excess.

Vostok is a remote region in East Antarctica, characterized by extreme climatic and environmental conditions (78°S,106°E, 3,488 m above sea level, annual mean temperature −55 °C, accumulation rate 21.5 kg−2⋅y−1 water equivalent). In addition, Vostok is located within the Antarctic vortex, which makes it sensitive to stratospheric input (up to 5%) (12). Only one-quarter of the precipitation originates from tropospheric snowfall, whereas 75% is due to hoar frost deposition and ice needle fallout (diamond dust), which may originate from the stratosphere (13, 14). The influence of such stratospheric water vapor input has been only marginally investigated even if the existence of mass independent fractionation (MIF) in the stratosphere is expected to strongly affect 17O-excess (15). This is because other effects become also prominent in these regions. First, at the observed very low temperature range (<−50 °C), the second-order parameters d-excess and 17O-excess are expected to show strong variations with condensation temperature (16). Second, the interpretation of water isotopic profiles is complicated by postdeposition effects at these very low accumulation sites.

The aim of this article is to identify the main drivers of water isotopologues changes at remote sites in East Antarctica. To achieve this, we present a fully integrated method, (i) combining measurements of  , d-excess, and 17O-excess on (ii) the seasonal, interannual, and glacial–interglacial timescales and (iii) comparing the data with AGCM and MCIM model outputs.

, d-excess, and 17O-excess on (ii) the seasonal, interannual, and glacial–interglacial timescales and (iii) comparing the data with AGCM and MCIM model outputs.

For interannual variations we present  , d-excess, and 17O-excess results of a snow pit, situated at the remote East Antarctic research facility of Vostok station covering the period from 1949 to 2008 (instrumental period), and compare them with the already available

, d-excess, and 17O-excess results of a snow pit, situated at the remote East Antarctic research facility of Vostok station covering the period from 1949 to 2008 (instrumental period), and compare them with the already available  , d-excess, and 17O-excess data of seasonal and glacial–interglacial timescales (17–19). To examine a possible stratospheric influence in tandem with MIF effects, we present a budget calculation of the oxygen 17O-anomaly of water from the stratosphere at the site of Vostok. These calculations together with considerations about postdeposition effects allow us to identify the important determinants of

, d-excess, and 17O-excess data of seasonal and glacial–interglacial timescales (17–19). To examine a possible stratospheric influence in tandem with MIF effects, we present a budget calculation of the oxygen 17O-anomaly of water from the stratosphere at the site of Vostok. These calculations together with considerations about postdeposition effects allow us to identify the important determinants of  , d-excess, and 17O-excess on the interannual timescale.

, d-excess, and 17O-excess on the interannual timescale.

Methodology

To disentangle the different influences (climate, postdeposition, and stratospheric influences) we focus on relative variations of the isotopologues rather than on their absolute values. The absolute values are indeed a complex result of many different influences whereas the relative variations should bring to light the driving processes of each isotopic change. To identify the climatic drivers (local temperature, moisture source relative humidity, and temperature) we also compare the observed relative variation with those simulated by an AGCM and a Rayleigh-distillation-type model. As precipitation intermittency at remote sites is a crucial factor for the interpretation of the interannual isotopic records of shallow ice cores, the AGCM is nudged to reanalyses over the instrumental period. Climate models do not take into account removal processes in the surface snow layers as well as diffusion of the water molecules in the firn. Still these effects have been shown to be important on the interannual scale (20, 21). To investigate snow removal effects we compare event-based seasonal precipitation data with the interannual variations of the snow pit data. Postdeposition effects on the snow are studied by an isotopic box model, accounting for postdeposition sublimation and recondensation effects and the diffusion theory of water isotopologues within the firn layer (22). Finally, the possibility of a stratospheric input is assessed by MIF signatures in the oxygen isotopic composition of the snow.

Snow Pit Analyses.

Several series of adjacent snow samples were collected from the same pit wall, from the surface down to 3.65 m for every 3 cm (23). Isotopic analyses were performed on 116 samples.  and

and  measurements were performed using the method of water fluorination, as described in ref. 9, followed by isotope ratio mass spectrometry using a Delta V mass spectrometer from ThermoFisher. The overall uncertainty for the 17O-excess data is ±6 ppm. The d-excess measurements were performed on a Picarro instrument (1σ of 1.4‰). In an earlier work (23) 124 samples from the same depth were analyzed for beryllium-10 (10Be) and ion chemistry [Na+, Mg2+, Ca2+, K+, (SO4)2−, Cl−, and (NO3)−]. The snow pit chronology was based on the identification of non-sea-salt sulfate spikes associated with the volcanic eruptions of Agung (Indonesia, March 1963, snow imprint in January 1964 ±1 y) and Pinatubo (Philippines, June 1991, snow imprint in January 1992 ±1 y). The gross β-radioactivity indicated the maximum fallout of the nuclear bomb tests, with their imprints in the snow in January 1955 ±1.5 y and January 1965 ±1.5 y, respectively (23). Because of the intermittency of the precipitation and the snow remobilization, the uncertainty of the absolute chronology may increase up to several years between reference horizons.

measurements were performed using the method of water fluorination, as described in ref. 9, followed by isotope ratio mass spectrometry using a Delta V mass spectrometer from ThermoFisher. The overall uncertainty for the 17O-excess data is ±6 ppm. The d-excess measurements were performed on a Picarro instrument (1σ of 1.4‰). In an earlier work (23) 124 samples from the same depth were analyzed for beryllium-10 (10Be) and ion chemistry [Na+, Mg2+, Ca2+, K+, (SO4)2−, Cl−, and (NO3)−]. The snow pit chronology was based on the identification of non-sea-salt sulfate spikes associated with the volcanic eruptions of Agung (Indonesia, March 1963, snow imprint in January 1964 ±1 y) and Pinatubo (Philippines, June 1991, snow imprint in January 1992 ±1 y). The gross β-radioactivity indicated the maximum fallout of the nuclear bomb tests, with their imprints in the snow in January 1955 ±1.5 y and January 1965 ±1.5 y, respectively (23). Because of the intermittency of the precipitation and the snow remobilization, the uncertainty of the absolute chronology may increase up to several years between reference horizons.

Interannual Simulations with a General Circulation Model.

To help interpret the results, we use simulations of the Laboratoire de Meteorologie Dynamique-Zoom (LMDZ) (24) AGCM. This model was run from 1958 to 2008 after 3 y of spin-up in 1958. To ensure that the interannual variability is simulated in phase with the one observed, the measured sea surface temperature and sea ice were prescribed following the atmospheric model intercomparison project (AMIP) (25), and the 3D fields of horizontal winds were nudged toward the ERA-40 reanalyses (26). Water isotopic diagnostics are included in this model (27) but  was not simulated over this period due to computer time limitations.

was not simulated over this period due to computer time limitations.

Results

Interannual Variability of  , d-Excess, and 17O-Excess.

, d-Excess, and 17O-Excess.

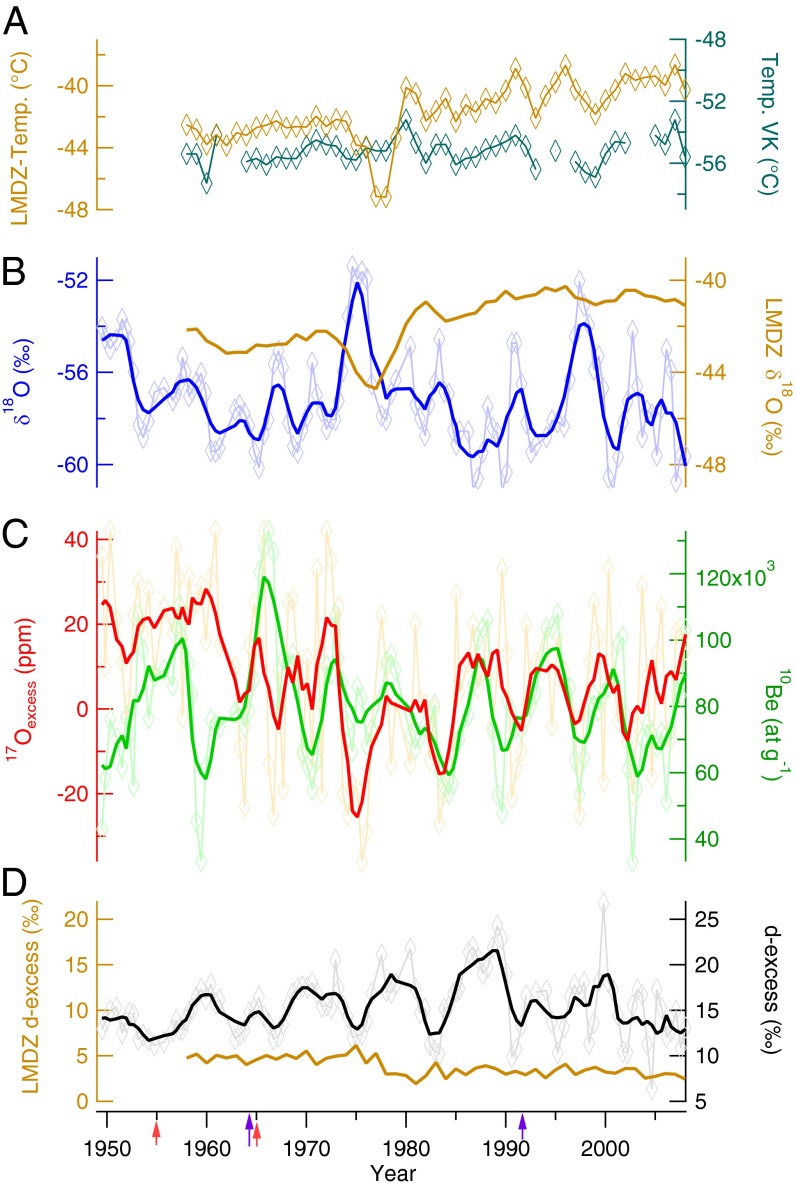

In the Vostok snow pit, over the period from 1949 to 2008,  , d-excess, and 17O-excess data show strong variations of, respectively, 10‰, 20‰, and 40 ppm (Fig. 1 and Dataset S1), which are much larger than the glacial–interglacial variations (respectively, 6 ‰, 3‰, and 20 ppm between the Last Glacial Maximum and the Early Holocene) (1, 19, 28). The seasonal variations are of the same amplitude as the interannual ones (17).

, d-excess, and 17O-excess data show strong variations of, respectively, 10‰, 20‰, and 40 ppm (Fig. 1 and Dataset S1), which are much larger than the glacial–interglacial variations (respectively, 6 ‰, 3‰, and 20 ppm between the Last Glacial Maximum and the Early Holocene) (1, 19, 28). The seasonal variations are of the same amplitude as the interannual ones (17).

Fig. 1.

(A) measured (Lower dark green curve, 44 points, 2 m above surface) and modeled (LMDZ, 51 points) local temperature. (B–D) Data (116 points): (B)  (and model), (C) 17O-excess and 10Be (23), and (D) d-excess (and model). Thick lines correspond to 5-point Boxcart smoothing. Red arrows: nuclear bomb tests in 1955 and 1965, respectively. Purple arrows: volcanic eruptions in 1963 (recorded 1964, Agung, Indonesia) and 1991 (recorded 1992, Pinatubo, Philippines).

(and model), (C) 17O-excess and 10Be (23), and (D) d-excess (and model). Thick lines correspond to 5-point Boxcart smoothing. Red arrows: nuclear bomb tests in 1955 and 1965, respectively. Purple arrows: volcanic eruptions in 1963 (recorded 1964, Agung, Indonesia) and 1991 (recorded 1992, Pinatubo, Philippines).

An anticorrelation between  and d-excess (R = −0.32) and between

and d-excess (R = −0.32) and between  and 17O-excess (R = −0.45) can be observed (Fig. 1 B–D). This study shows that there is a distinguished relation between

and 17O-excess (R = −0.45) can be observed (Fig. 1 B–D). This study shows that there is a distinguished relation between  and 17O-excess for the different timescales: On the seasonal and glacial scale

and 17O-excess for the different timescales: On the seasonal and glacial scale  and 17O-excess are varying in tandem (Rglacial = 0.59, Rseason = 0.78) (17, 19), whereas on the interannual scale 17O-excess and

and 17O-excess are varying in tandem (Rglacial = 0.59, Rseason = 0.78) (17, 19), whereas on the interannual scale 17O-excess and  vary in antiphase (Fig. 2 and Table 1, first three rows).

vary in antiphase (Fig. 2 and Table 1, first three rows).

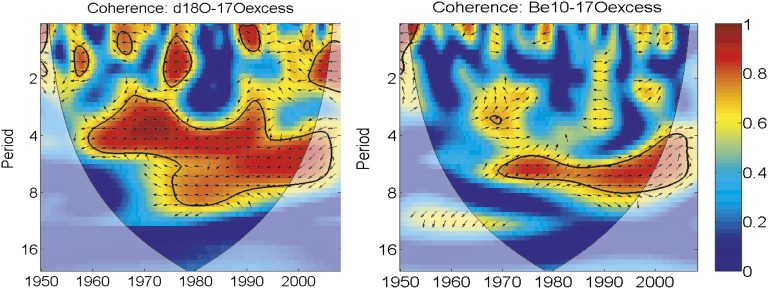

Fig. 2.

(Left to Right) Coherence wavelet analyses (29, 30) revealed an anticorrelation (arrows pointing to the left) between  and 17O-excess and a correlation (arrows pointing to the right) between 10Be and 17O-excess. Data were interpolated with the statistic software R (31). Significance (95% level) was tested by comparison with the red noise wavelet pattern. Significant area is surrounded by a black line. Area outside cone of influence, edge effects of continuous wavelet transformation, cannot be neglected.

and 17O-excess and a correlation (arrows pointing to the right) between 10Be and 17O-excess. Data were interpolated with the statistic software R (31). Significance (95% level) was tested by comparison with the red noise wavelet pattern. Significant area is surrounded by a black line. Area outside cone of influence, edge effects of continuous wavelet transformation, cannot be neglected.

Table 1.

Sensitivity of δ18O, d-excess, and 17O-excess on climatic factors, postdeposit, and stratospheric impact

, ‰ , ‰ |

Δd-excess, ‰ | Δ17O-excess, ppm |  |

|

|

| Variability | |||||

| Seasonal | 10 | 20 | 40 | −2 | +4 ppm⋅‰−1 |

| Interannual | 10 | 20 | 40 | −3 | −4 ppm⋅‰−1 |

| Glacial | 6 | 3 | 20 | +2 | +3.3 ppm⋅‰−1 |

| Climatic factors | |||||

| Relative humidity | 0.15‰⋅%−1 | −0.1‰⋅%−1 | −1 ppm⋅%−1 | −0.67 | −6.7 ppm⋅‰−1 |

| SST | −0.5‰⋅°C−1 | 1.4‰⋅°C−1 | 0.45 ppm⋅° C−1 | −2.8 | −0.9 ppm⋅‰−1 |

|

0.95 | 3 | 0 | 3.16 | 0 |

| Slow | 1.15‰⋅°C−1 | −1.7‰⋅°C−1 | −0.15 ppm⋅°C−1 | −1.47 | −0.13 ppm⋅‰−1 |

| Shigh | 1.7‰⋅°C −1 | −2.9‰⋅°C−1 | 3.6 ppm⋅°C−1 | −1.7 | 2.12 ppm⋅‰−1 |

| Postdeposit | |||||

| 20% sublimation | No isotopic fractionation |

||||

| 20% recondensation | +2.1‰ | −2.8‰ | −43 ppm | −1.33 | −20.2 ppm⋅‰−1 |

| Strato-impact | |||||

| 0.014% STE | −0.013‰ | +0.07‰ | +0.2 ppm | −5.2 | −16.87 ppm⋅‰−1 |

| 2% STE | −1.9‰ | +9.7‰ | +32 ppm | −5.2 | −17.15 ppm⋅‰−1 |

For variability, columns 2–4 show absolute variations of  , d-excess, and 17O-excess for three different timescales. Columns 5 and 6 show slope

, d-excess, and 17O-excess for three different timescales. Columns 5 and 6 show slope  vs. second-order parameters. Positive (negative) sign of slope indicates (anti)correlation. For climatic factors, postdeposit, and strato-impact, main determinants of the

vs. second-order parameters. Positive (negative) sign of slope indicates (anti)correlation. For climatic factors, postdeposit, and strato-impact, main determinants of the  , d-excess, and 17O-excess, Slow and Shigh are the supersaturation of the air of 8% and 16%, respectively. For strato-impact, 2% of Vostok’s moisture stems from the stratosphere. STE, stratosphere-troposphere exchange.

, d-excess, and 17O-excess, Slow and Shigh are the supersaturation of the air of 8% and 16%, respectively. For strato-impact, 2% of Vostok’s moisture stems from the stratosphere. STE, stratosphere-troposphere exchange.

The classical explanation for  variations in polar snow is local temperature. Fig. 1A shows the measured monthly mean temperature (2 m above surface) at the Vostok research station. There is no significant correlation between the surface temperature and

variations in polar snow is local temperature. Fig. 1A shows the measured monthly mean temperature (2 m above surface) at the Vostok research station. There is no significant correlation between the surface temperature and  on the interannual timescale. This finding is not unexpected because of the uncertainty of the snow pit chronology and the precipitation intermittency at this very low accumulation site. Even if the temperature and

on the interannual timescale. This finding is not unexpected because of the uncertainty of the snow pit chronology and the precipitation intermittency at this very low accumulation site. Even if the temperature and  record cannot be directly compared in the time series, we can still investigate the climatic impact on the water isotopic profile, by comparing the relative variations and phasing between

record cannot be directly compared in the time series, we can still investigate the climatic impact on the water isotopic profile, by comparing the relative variations and phasing between  , d-excess ,and 17O-excess with those simulated by an AGCM. It should be noted that such a comparison is quite limited, because the LMDZ simulates only tropospheric snowfall events and does not take into account ice needle fallout. Moreover, the modeled

, d-excess ,and 17O-excess with those simulated by an AGCM. It should be noted that such a comparison is quite limited, because the LMDZ simulates only tropospheric snowfall events and does not take into account ice needle fallout. Moreover, the modeled  level is 10‰ too high, which can be explained by too high a site temperature. Also, opposite to the seasonal record, the large interannual variability of

level is 10‰ too high, which can be explained by too high a site temperature. Also, opposite to the seasonal record, the large interannual variability of  and d-excess cannot be reproduced by the model. The LMDZ output shows a strong correlation between

and d-excess cannot be reproduced by the model. The LMDZ output shows a strong correlation between  and 17O-excess (10) and a strong anticorrelation between d-excess and

and 17O-excess (10) and a strong anticorrelation between d-excess and  (R = −0.56), which corresponds well to the seasonal and glacial–interglacial observations. This strong link between

(R = −0.56), which corresponds well to the seasonal and glacial–interglacial observations. This strong link between  and the site temperature (R = 0.88) is easily predicted by the equilibrium and kinetic fractionation during the Rayleigh distillation toward low temperatures, as observed in any isotopic distillation model.

and the site temperature (R = 0.88) is easily predicted by the equilibrium and kinetic fractionation during the Rayleigh distillation toward low temperatures, as observed in any isotopic distillation model.

To identify the causes of the large isotopic variations observed on the snow pit that are not included in the AGCM, a systematic investigation of correlations between the different available tracers has been performed. The most prominent feature is an anticorrelation between  and 17O-excess during the period of 1960–2008 and a correlation between 10Be and 17O-excess for the period of 1970–2008 (Fig. 2).

and 17O-excess during the period of 1960–2008 and a correlation between 10Be and 17O-excess for the period of 1970–2008 (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Climatic Effects.

We have shown that the LMDZ nudged to reanalyses is able to simulate the interannual temperature variations, but fails in properly simulating interannual variations of  and d-excess. Even if the model properly reproduces

and d-excess. Even if the model properly reproduces  vs. 17O-excess correlation on a seasonal scale, data–model comparisons have evidenced weaknesses for properly describing

vs. 17O-excess correlation on a seasonal scale, data–model comparisons have evidenced weaknesses for properly describing  and especially d-excess and 17O-excess in remote regions of Antarctica (10). Indeed, the LMDZ does not take into account mechanisms like the Bergeron–Findesein process (11), overestimates the temperature at Vostok, and underestimates the relative humidity influence on 17O-excess and d-excess at evaporation (32). As a consequence, to quantify the climatic determinants of

and especially d-excess and 17O-excess in remote regions of Antarctica (10). Indeed, the LMDZ does not take into account mechanisms like the Bergeron–Findesein process (11), overestimates the temperature at Vostok, and underestimates the relative humidity influence on 17O-excess and d-excess at evaporation (32). As a consequence, to quantify the climatic determinants of  , d-excess, and 17O-excess with correct temperature and source climatic inputs, we use a Rayleigh-type model (mixed-cloud isotopic model (refs. 11 and 18 and SI Text). In the MCIM, like in all AGCM equipped with water isotopologues, the supersaturation (S) of air is the main tuning parameter of simulated d-excess and 17O-excess. This is especially important for remote regions with extremely low temperature, because S is classically parameterized to increase with decreasing temperature. Model simulations revealed a much larger sensitivity to S for 17O-excess than for

, d-excess, and 17O-excess with correct temperature and source climatic inputs, we use a Rayleigh-type model (mixed-cloud isotopic model (refs. 11 and 18 and SI Text). In the MCIM, like in all AGCM equipped with water isotopologues, the supersaturation (S) of air is the main tuning parameter of simulated d-excess and 17O-excess. This is especially important for remote regions with extremely low temperature, because S is classically parameterized to increase with decreasing temperature. Model simulations revealed a much larger sensitivity to S for 17O-excess than for  and d-excess (Table 1, rows Slow and Shigh). For example, a concomitant decrease of

and d-excess (Table 1, rows Slow and Shigh). For example, a concomitant decrease of  and 17O-excess combined with an increase of d-excess can be simply explained by a decrease of local temperature in the case of a relatively high supersaturation (17, 18). Although this local temperature effect is satisfying to explain a large part of the water isotopic variations on the seasonal scale at Vostok, it fails to explain the large and anticorrelated variations of

and 17O-excess combined with an increase of d-excess can be simply explained by a decrease of local temperature in the case of a relatively high supersaturation (17, 18). Although this local temperature effect is satisfying to explain a large part of the water isotopic variations on the seasonal scale at Vostok, it fails to explain the large and anticorrelated variations of  and 17O-excess on an interannual scale. Our assumption of S being only a function of condensation temperature can be challenged. Indeed, an increase of dust load in the atmosphere is expected to decrease the supersaturation by providing additional condensation nuclei (19). In our snow pit data we did not observe any significant relationship between 17O-excess and Ca2+ (proxy of dust load) and hence we rule out that interannual 17O-excess variations are governed by dust load, linked to supersaturation. After the parameterization of S, the second important determinant of 17O-excess variation in the MCIM is relative humidity at the site of evaporation. However, relative humidity changes are unlikely to determine the large interannual variations of 17O-excess, because this would require unrealistic large (±40%) interannual variations in relative humidity over the ocean (Table 1).

and 17O-excess on an interannual scale. Our assumption of S being only a function of condensation temperature can be challenged. Indeed, an increase of dust load in the atmosphere is expected to decrease the supersaturation by providing additional condensation nuclei (19). In our snow pit data we did not observe any significant relationship between 17O-excess and Ca2+ (proxy of dust load) and hence we rule out that interannual 17O-excess variations are governed by dust load, linked to supersaturation. After the parameterization of S, the second important determinant of 17O-excess variation in the MCIM is relative humidity at the site of evaporation. However, relative humidity changes are unlikely to determine the large interannual variations of 17O-excess, because this would require unrealistic large (±40%) interannual variations in relative humidity over the ocean (Table 1).

Postdeposition Effects.

In addition to climatic factors we also examined the possible influence of postdeposition effects on the water isotopic composition. If wind-driven snow removal were the main factor of the  variation, the same correlation between

variation, the same correlation between  and 17O-excess as in seasonal event-based data should be preserved in the interannual data, because when the snow mixes, its compounds mix in the same way. Because an anticorrelation between

and 17O-excess as in seasonal event-based data should be preserved in the interannual data, because when the snow mixes, its compounds mix in the same way. Because an anticorrelation between  and 17O-excess has been observed in the snow pit data, the only remaining postdeposition process to be taken into account is isotopic fractionation in the firn. Diffusion of water molecules has been shown to affect the record of water isotopic profiles in Greenland (22). However, in our case starting from

and 17O-excess has been observed in the snow pit data, the only remaining postdeposition process to be taken into account is isotopic fractionation in the firn. Diffusion of water molecules has been shown to affect the record of water isotopic profiles in Greenland (22). However, in our case starting from  and 17O-excess seasonal signals being in phase, the model predicts only a dampening of the amplitudes of the two signals and no phase change. Actually, the only way to build an anticorrelation between

and 17O-excess seasonal signals being in phase, the model predicts only a dampening of the amplitudes of the two signals and no phase change. Actually, the only way to build an anticorrelation between  and 17O-excess is to invoke the situation where the precipitated snow is partly sublimated (here 20%) at a relatively high temperature

and 17O-excess is to invoke the situation where the precipitated snow is partly sublimated (here 20%) at a relatively high temperature  (here −20 °C) and condensed again onto the snow pack at a lower temperature Tcond (here −55 °C). Observations showed that sublimation (as high as 10–20% of the total precipitation) mainly happens in December and January, when the air temperature is between −15 °C and −30 °C. Taking into account the associated fractionation (SI Text), sublimation and subsequent condensation of snow would lead to an increase of

(here −20 °C) and condensed again onto the snow pack at a lower temperature Tcond (here −55 °C). Observations showed that sublimation (as high as 10–20% of the total precipitation) mainly happens in December and January, when the air temperature is between −15 °C and −30 °C. Taking into account the associated fractionation (SI Text), sublimation and subsequent condensation of snow would lead to an increase of  (+2.1‰), which is in antiphase with the resulting decrease of d-excess (−2.8‰) and 17O-excess (−43 ppm) (Table 1).

(+2.1‰), which is in antiphase with the resulting decrease of d-excess (−2.8‰) and 17O-excess (−43 ppm) (Table 1).

On the basis of the numbers in Table 1, assuming an extreme case of postdepositional sublimation and recondensation, relatively high  would still correspond to relatively high 17O-excess. Furthermore, strong sublimation effects have been reported for sites with strong katabatic winds and for relatively high temperatures (33), whereas Vostok is marked by very low temperatures and moderate wind speed (13). In addition, an experiment was performed to look at the isotopic evolution of the Vostok snow when it is exposed to relatively dry conditions. The snow isotopic composition evolved with an increase in both

would still correspond to relatively high 17O-excess. Furthermore, strong sublimation effects have been reported for sites with strong katabatic winds and for relatively high temperatures (33), whereas Vostok is marked by very low temperatures and moderate wind speed (13). In addition, an experiment was performed to look at the isotopic evolution of the Vostok snow when it is exposed to relatively dry conditions. The snow isotopic composition evolved with an increase in both  and 17O-excess at the end of the experiment. Therefore, postdeposition effects cannot explain the changed relationship between

and 17O-excess at the end of the experiment. Therefore, postdeposition effects cannot explain the changed relationship between  and 17O-excess from the correlation that is observed on the seasonal scale (where postdeposition effects can be excluded) to the anticorrelation that is observed on the interannual scale.

and 17O-excess from the correlation that is observed on the seasonal scale (where postdeposition effects can be excluded) to the anticorrelation that is observed on the interannual scale.

Stratospheric Influences.

One way to explain the large variations of 17O-excess observed at the interannual timescale is to invoke water flux from the stratosphere (34). This effect has already been proposed to explain the large interannual variability of tritium in remote regions of Antarctica (35).

In addition to our data, model studies also suggest that stratospheric air reaches the Antarctic surface (36, 37). Stratospheric air is marked by a very low (4–6.5 ppm) water content (15)) and its influence on the isotopic composition of tropospheric water vapor is in general probably small. However, things may be different at a station like Vostok that is characterized by an extremely low water vapor content (relative humidity = 67% at −55 °C) (13) and a very low accumulation rate. In this section we examine the possible influence of stratospheric water vapor under the consideration of the stratosphere to troposphere exchange (STE) due to the Brewer–Dobson circulation (38, 39) and the isotopic composition of stratospheric H2O.

About half of the stratospheric water content has a tropospheric origin, whereas the other half is produced via H-abstraction from methane (and other H-bearing species, HO2 and HNO3) through the OH radical (40, 41):

Due to large H2O recycling via HOx and NOx that exceeds the net H2O production, the newly formed H2O and the recycled tropospheric H2O carry the same isotopic signature (15). Furthermore, model studies have shown that stratospheric H2O carries a large 17O-anomaly of up to 30‰ (15) that stems from MIF that originates from the O3 molecule (42, 43). Zahn et al. (15) have shown that the 17O-anomaly depends on their model specifications and on altitude, and for our estimations we take 17O-anomaly = 3‰, which corresponds to their most robust model output and tropical tropopause layer (TTL) of ≈15km. The above 17O-anomaly of 3‰ is in fairly good agreement with the stratospheric water vapor 17O-excess measurements of Franz and Röckmann (44).

The annual gross flux of stratospheric vapor into the troposphere (STE) was estimated at 1.73 × 104 kg⋅s−1 on a global average, accounting for only 0.014% of Vostok’s precipitation (ref. 36 and SI Text). However, this number may be much larger at Vostok because most of the descending flux from the stratosphere occurs at high latitudes between 40° and 90° and also because large seasonal to interannual variations of the STE were proposed (45). For an estimation of the stratospheric contribution we have used the model study of Stohl and Sodemann (37), with 2% of the air near the surface of the Antarctic plateau having a stratospheric origin. This is a conservative assumption, because studies have shown that 5% of the precipitation in Antarctica during winter stems from the stratosphere (12).

Table 1 displays the stratospheric influence on 17O-excess (+32 ppm),  (−1.9‰), and d-excess (+9.7‰), under the assumption of 2% of Vostok’s precipitation having a stratospheric origin. Associated influences of

(−1.9‰), and d-excess (+9.7‰), under the assumption of 2% of Vostok’s precipitation having a stratospheric origin. Associated influences of  and d-excess are due to the very strong Rayleigh distillation effects within the cold TTL. An aircraft-based measurement campaign across the TTL revealed very depleted values of

and d-excess are due to the very strong Rayleigh distillation effects within the cold TTL. An aircraft-based measurement campaign across the TTL revealed very depleted values of  of −150‰ in tandem with very high values of d-excess of ≈500‰ (46). Stratospheric influence could at least partly explain the observed anticorrelations between

of −150‰ in tandem with very high values of d-excess of ≈500‰ (46). Stratospheric influence could at least partly explain the observed anticorrelations between  and 17O-excess and d-excess (Table 1 and SI Text).

and 17O-excess and d-excess (Table 1 and SI Text).

To summarize, there are several ways to explain the interannual water isotopologue variations within a period of 2.5–5 y. Even if we cannot make a strong argument from this periodicity, close to the stratigraphic noise in such a low accumulation (21) site, we note that it is close to the Southern Annual Mode (SAM) or Antarctic circumpolar wave (ACW) periodicity (47). The SAM influences local temperature of Antarctica and source-to-site tropospheric transportation (e.g., refs. 23, 48, 49). As explained above (Table 1), these mechanisms cannot explain the anticorrelation between  and 17O-excess, which is our most robust observation. We have shown that seasonal or interannual variations of STE within the presented range (0.014% and 2%) can explain a large part of the 17O-excess interannual variations (Table 1) and, most important, they may explain the anticorrelation between

and 17O-excess, which is our most robust observation. We have shown that seasonal or interannual variations of STE within the presented range (0.014% and 2%) can explain a large part of the 17O-excess interannual variations (Table 1) and, most important, they may explain the anticorrelation between  and 17O-excess, if the stratospheric influence happens mainly during the cold periods. Stratospheric inputs may also be seen in 10Be variability, as suggested by the coherence of 17O-excess with 10Be (Figs. 1C and 2). Indeed, variations in 10Be concentration at Vostok were shown to result from the combined influences of 10Be production, modulated by solar activity; modulation of tropospheric air mass transportation (linked to SAM and ACW); and stratospheric input (23). Because of these numerous influences on 10Be, we do not expect a perfect correlation between 10Be and 17O-excess. Moreover, we note that the correlation between 10Be and 17O-excess is not significant before 1970. This may be due to the effect of diffusion increasing with depth in the firn. As for the deposition that is not the same for 10Be (dry deposition) and 17O-excess (wet deposition), the diffusion in the firn is different for both tracers, i.e., much smaller for 10Be compared with water isotopic diffusion.

and 17O-excess, if the stratospheric influence happens mainly during the cold periods. Stratospheric inputs may also be seen in 10Be variability, as suggested by the coherence of 17O-excess with 10Be (Figs. 1C and 2). Indeed, variations in 10Be concentration at Vostok were shown to result from the combined influences of 10Be production, modulated by solar activity; modulation of tropospheric air mass transportation (linked to SAM and ACW); and stratospheric input (23). Because of these numerous influences on 10Be, we do not expect a perfect correlation between 10Be and 17O-excess. Moreover, we note that the correlation between 10Be and 17O-excess is not significant before 1970. This may be due to the effect of diffusion increasing with depth in the firn. As for the deposition that is not the same for 10Be (dry deposition) and 17O-excess (wet deposition), the diffusion in the firn is different for both tracers, i.e., much smaller for 10Be compared with water isotopic diffusion.

The question arises why the MIF signature of 17O-excess is observed at interannual but not at seasonal and glacial scales. It should be noted that the seasonal record (17) contains only the measurements of 16 precipitation events, 9 of them being associated with snowfall and only 4 of them containing ice needles (in addition to hoar frost). Thus, the 16 seasonal samples do not represent an average precipitation composition of 1 y (up to 91% clear sky precipitation) and are underestimating clear sky precipitation with possible stratospheric origin and much larger 17O-excess due to MIF effects in the stratosphere. Therefore, we do not expect an anticorrelation between  and 17O-excess in the seasonal record.

and 17O-excess in the seasonal record.

The correlation between  and 17O-excess on glacial–interglacial transition is difficult to explain with the stratospheric input as observed on the interannual scale. Still, it is not easy to predict the 17O-excess signature due to stratospheric input on this long timescale because of numerous modifications that may occur: First, the strength of the polar vortex and thus the input of water from the stratosphere may be influenced not only by temperature at this timescale but also by greenhouse gas (including ozone, methane and water vapor) concentrations that control the vertical temperature gradient. Second, due to possible changes in the ozone concentration, the stratospheric chemistry and therefore also the 17O-anomaly may differ from the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) to the present day.

and 17O-excess on glacial–interglacial transition is difficult to explain with the stratospheric input as observed on the interannual scale. Still, it is not easy to predict the 17O-excess signature due to stratospheric input on this long timescale because of numerous modifications that may occur: First, the strength of the polar vortex and thus the input of water from the stratosphere may be influenced not only by temperature at this timescale but also by greenhouse gas (including ozone, methane and water vapor) concentrations that control the vertical temperature gradient. Second, due to possible changes in the ozone concentration, the stratospheric chemistry and therefore also the 17O-anomaly may differ from the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) to the present day.

Summary and Conclusions

We measured the triple oxygen isotopic composition of a snow pit from the vicinity of Vostok (East Antarctica) on the interannual timescale. We observed large variations in the records of  (10‰), d-excess (20‰), and 17O-excess (40 ppm), during the period of 1949–2008. We compared the water isotopic data with the output of an AGCM (LMDZ) and a simpler Rayleigh-type model (MCIM). The AGCM was able to reconstruct the seasonal water isotopic variations, as well as the variability of the site temperature on the interannual scale, but failed to capture the anticorrelation between

(10‰), d-excess (20‰), and 17O-excess (40 ppm), during the period of 1949–2008. We compared the water isotopic data with the output of an AGCM (LMDZ) and a simpler Rayleigh-type model (MCIM). The AGCM was able to reconstruct the seasonal water isotopic variations, as well as the variability of the site temperature on the interannual scale, but failed to capture the anticorrelation between  and 17O-excess on the interannual scale. These findings were confirmed by the MCIM and lead us to the conclusion that interannual isotopic variance at Vostok is not solely determined by changing surface climatic conditions.

and 17O-excess on the interannual scale. These findings were confirmed by the MCIM and lead us to the conclusion that interannual isotopic variance at Vostok is not solely determined by changing surface climatic conditions.

We presented the possible influence of intermittency of precipitation and postdeposition processes and showed that such effects cannot explain the significant anticorrelation between  and 17O-excess. Stratospheric water intrusions would mainly increase 17O-excess and d-excess, whereas

and 17O-excess. Stratospheric water intrusions would mainly increase 17O-excess and d-excess, whereas  would undergo a slight decrease. The observed anticorrelations between

would undergo a slight decrease. The observed anticorrelations between  on the one hand and d-excess and 17O-excess on the other hand could be the consequence of stratospheric influences. In addition, the observed correlation between 17O-excess and 10Be may be a consequence of stratospheric air intrusion that modulates both parameters.

on the one hand and d-excess and 17O-excess on the other hand could be the consequence of stratospheric influences. In addition, the observed correlation between 17O-excess and 10Be may be a consequence of stratospheric air intrusion that modulates both parameters.

Finally our work has two important implications:

i) The comparison between our data and the models clearly shows that interannual isotopic variations at very low accumulation sites in Antarctica should not be interpreted as a proxy for a change in surface climatic conditions. Other mechanisms can superimpose the surface climatic determinants on this timescale. However, at this stage this conclusion does not preclude the use of water isotopologues as proxies of climatic conditions (e.g., local temperature) on longer timescales.

ii) Our finding of a unique isotopic signature of stratospheric water vapor could be further confirmed by comparisons with other tracers of stratospheric input (e.g., tritium) and may allow the use of 17O-excess as a tracer of stratospheric influences at sites with low accumulation rates for times reaching much farther back in the past.

Outlook

One way to further investigate the stratospheric water input in remote East Antarctica would be to lead the same multiproxy snow pit study at a more coastal site. It would also be of great interest to compare real-time triple oxygen isotopic measurements of Antarctic water vapor and to compare these data with regional meteorological models. Also, more precise measurements of the stratospheric water vapor isotopic signature (especially of 17O-excess) are needed to further quantify their influence on tropospheric water isotopologues.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the authors of ref. 29, who provided the Matlab code that we used to perform the wavelet analysis, and the two reviewers whose comments significantly improved the quality of this work. We also thank Guillaume Tremoy, Alexandre Cauquoin, Elise Fourre, and Philippe Jean-Baptiste for fruitful discussions about the topic of water isotopologues and 10Be. The sampling has been carried out in the vicinity of the Vostok station with the support of the Russian Foundation for Basic Research, whereas the experimental work done at Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement (LSCE) was funded by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR Composition Isotopique TRiple de l'OxygeNe: de Nouveaux Indicateurs de l'Evolution de la BiosphEre et du cycle hydRologique). Experimental work (10Be analysis) at Centre Europeen de Recherche et d'Enseignement des Geosciences de l'Environnement was a contribution to the VOLSOL project and was funded by Grant ANR-09-BLAN-0003-01. We also thank the Marie-Curie Initial Training Network on Mass-Independent Fractionation (FP7), which funded Renato Winkler’s PhD at LSCE.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1215209110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Petit JR, et al. Climate and atmospheric history of the past 420,000 years from the Vostok ice core, Antarctica. Nature. 1999;399:429–436. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jouzel J, et al. Orbital and millennial Antarctic climate variability over the past 800,000 years. Science. 2007;317(5839):793–796. doi: 10.1126/science.1141038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

3.Merlivat L. Molecular diffusivities of H2O, 2HHO16, and

in gases. J Chem Phys. 1978;69:2864–2871. [Google Scholar]

in gases. J Chem Phys. 1978;69:2864–2871. [Google Scholar] - 4.Lorius C, Merlivat L, Jouzel J, Pourchet M. A 30’000-yr isotope climatic record from Antarctic ice. Nature. 1979;280:644–668. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jouzel J, et al. Magnitude of isotope/temperature scaling for interpretation of Central Antarctic ice cores. J Geophys Res. 2003;108:4361–4372. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masson-Delmotte V, et al. A review of Antarctic surface snow isotopic composition: Observations, atmospheric circulation and isotopic modelling. J Clim. 2008;21(13):3359–3387. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sime LC, Wolff EW, Oliver KIC, Tindall JC. Evidence for warmer interglacials in East Antarctic ice cores. Nature. 2009;462(7271):342–345. doi: 10.1038/nature08564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dansgaard W. Stable isotopes in precipitation. Tellus. 1964;169:436–468. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barkan E, Luz B. High precision measurements of 17O/16O and 18O/16O ratios in H2O. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2005;19(24):3737–3742. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Risi C, Landais A, Winkler R, Vimeux F (2012) What controls the spatial and temporal distribution of d-excess and 17O-excess in precipitation? A general circulation model study. Clim Past Discuss 8:5493–5543.

- 11.Ciais P, Jouzel J. Deuterium and oxygen 18 in precipitation: Isotopic model, including mixed cloud processes. J Geophys Res. 1994;99:16793–16803. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roscoe HK. Possible descent across “Tropopause” in Antarctic winter. Adv Space Res. 2004;33:1048–1052. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vostok Meteorological Data Website. Available at http://www.aari.aq. Accessed August 10, 2012.

- 14.Ekaykin AA, et al. 2004. The changes in isotope composition and accumulation of snow at Vostok station, East Antarctica, over the past 200 years. Ann Glaciol 39(1):569–575.

- 15.Zahn A, Franz P, Bechtel C, Gross J-U, Röckmann T. Modelling the budget of middle atmospheric water vapour isotopes. Atmos Chem Phys. 2006;6:2073–2090. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uemura R, et al. Ranges of moisture-source temperatures estimated from Antarctic ice core stable isotope records over the glacial-interglacial cycle. Clim Past Discuss. 2012;8:391–434. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landais A, Ekaykin A, Barkan E, Winkler R, Luz B. Seasonal variations of d-excess and 17O-excess in snow at the Vostok station (East Antarctica) J Glaciol. 2012;58:725–733. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winkler R, et al. Deglaciation records of 17O-excess in East Antarctica: Reliable reconstruction of oceanic normalized relative humidity from coastal sites. Clim Past Discuss. 2012;8:1–16. [Google Scholar]

-

19.Landais A, Barkan E, Luz B. Record of

and 17O-excess in ice from Vostok Antarctica during the last 150 000 years. Geophys Res Lett. 2008;35(2):L02709–L02713. [Google Scholar]

and 17O-excess in ice from Vostok Antarctica during the last 150 000 years. Geophys Res Lett. 2008;35(2):L02709–L02713. [Google Scholar] - 20.Petit JR, Jouzel J, Pourchet M, Merlivat L. A detailed study of snow accumulation and stable isotope content in Dome C (Antarctica) J Geophys Res. 1982;87:4301–4308. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ekaykin AA, Lipenkov VY, Barkov NI, Petit JR, Masson-Delmotte V. 2002. Spatial and temporal variability in isotope composition of recent snow in the vicinity of Vostok station, Antarctica: Implications for ice-core record interpretation, Ann Glaciol 35(1):181–186.

- 22.Johnsen SJ, et al. Diffusion of stable isotopes in polar firn and ice: The isotope effect in firn diffusion. In: Hondoh T, editor. Physics of Ice Core Records. 2000. (Hokkaido Univ Press, Sapporo, Japan), pp 121–140. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Baroni M, Bard E, Petit JR, Magand O, Bourles D (2011) Volcanic and solar activity, and atmospheric circulation influences on cosmogenic 10Be fallout at Vostok and Concordia (Antarctica) over the last 60 years. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 75(22):7132–7146.

- 24.Hourdin F, et al. The LMDZ general circulation model: Climate performance and sensitivity to parametrized physics with emphasis on tropical convection. Clim Dyn. 2006;19(15):3445–3482. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gates WL. AMIP the Atmospheric Model Intercomparison Project. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 1992;73:1962–1970. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uppala S, et al. The ERA-40 reanalysis. Q J R Meteorol Soc. 2005;131:2961–3012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Risi C, et al. Understanding the 17O-excess glacial-interglacial variations in Vostok precipitation. J Geophys Res. 2010;115:D10112. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vimeux F, Masson V, Jouzel J, Stievenard M, Petit JR. Glacial-interglacial changes in the ocean surface conditions in the Southern Hemisphere. Nature. 1999;398:410–413. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grinsted A, Moore JC, Jevrejeva S. Application of the cross wavelet transform and wavelet coherence to geophysical time series. Nonlinear Process Geophys. 2004;11:561–566. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torrence C, Compo GP. A practical guide to wavelet analysis. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 1998;79:61–78. [Google Scholar]

- 31.R Development Core Team 2011. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing Vienna). Available at http://www.R-project.org.

- 32.Uemura R, Barkan E, Abe O, Luz B. Triple isotopic composition of oxygen in atmospheric vapour. Geophys Res Lett. 2010;37:L04402–L04405. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujii Y, Kusunoki K. The role of sublimation and condensation in the formation of ice sheet surface at Mizuho Station, Antarctica. J Geophys Res. 1982;87(C6):4293–4300. [Google Scholar]

-

34.Miller MF. Comment on “Record of

and 17O-excess in ice from Vostok Antarctica during the last 150,000 years” by Amaelle Landais et al. Geophys Res Lett. 2008;35:L23709. [Google Scholar]

and 17O-excess in ice from Vostok Antarctica during the last 150,000 years” by Amaelle Landais et al. Geophys Res Lett. 2008;35:L23709. [Google Scholar] - 35.Fourre E, et al. Past and recent tritium levels in Arctic and Antarctic polar caps. EPSL. 2006;245:56–64. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang H, Tung KK. Cross-isentropic stratosphere-troposphere exchange of mass and water vapour. J Geophys Res. 1996;101:9413–9423. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stohl A, Sodemann H. Characteristics of the atmospheric transport into the Antarctic troposphere. J Geophys Res. 2010;115(D2):D02305–D02320. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dobson GMB. Origin and distribution of polyatomic molecules in the atmosphere. Proc R Soc Lond A Math Phys Sci. 1956;236:187–193. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brewer AW. Evidence for a world circulation provided by the measurement of helium an water vapour distribution in the stratosphere. Q J R Meteorol Soc. 1949;75:351–363. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lyons JR. Transfer of mass-independent fractionation in ozone to other oxygen-containing radicals in the atmosphere. Geophys Res Lett. 2001;17:3231–3234. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dessler AE, Hintsa EJ, Weinstock EM, Anderson JG, Chan KR. Mechanisms controlling water vapour in the lower stratosphere: “A tale of two stratospheres”. J Geophys Res. 1995;23:23167–23172. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thiemens MH. Mass-independent isotope effects in planetary atmospheres and the early solar system. Science. 1999;283(5400):341–345. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thiemens MH, Heidenreich JE., 3rd The mass-independent fractionation of oxygen: A novel isotope effect and its possible cosmochemical implications. Science. 1983;219(4588):1073–1075. doi: 10.1126/science.219.4588.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

44.Franz P, Röckmann T. High-precision isotope measurements of H2O,

,

,  and

and  of water vapour in the southern lowermost stratosphere. Atmos Chem Phys. 2005;5:2949–2959. [Google Scholar]

of water vapour in the southern lowermost stratosphere. Atmos Chem Phys. 2005;5:2949–2959. [Google Scholar] - 45.Karpechko A, et al. The water vapour distribution in the Arctic lowermost stratosphere during the LAUTLOS campaign and related transport processes including stratosphere-troposphere exchange. Atmos Chem Phys. 2007;7:107–119. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sayres DS, et al. Influence of convection on the water isotopic composition of the tropical tropopause layer and tropical stratosphere. J Geophys Res. 2010;115:D00J20. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Venegas SA. 2003. The Antarctic Circumpolar Wave: A combination of two signals? Am Meteorol Soc 16(15):2509–2525.

- 48.Naik SS, Thamban M, Laluraj CM, Redkar BL, Chaturvedi A. A century of climate variability in central Dronning Maud Land, East Antarctica, and its relation to Southern Annual Mode and El Nino-Southern Oscillation. J Geophys Res. 2010;115(16):D16102–D16113. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schneider DP, et al. Antarctic temperatures over the past two centuries from ice cores. Geophys Res Lett. 2006;33:L16707–L16711. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.