Abstract

BACKGROUND

The relationship between diabetes, GERD symptoms and acid-related mucosal damage has not been well studied.

AIMS

To better quantify risk of acid-related mucosal damage among patients with and without diabetes.

METHODS

A prospective study using 10 sites from the Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative (CORI) National Endoscopy Database surveyed patients undergoing EGD by telephone within 30 days on medical history, symptoms and demographics. Varices and feeding tube indications were excluded. Acid-related damage was defined as any of these findings recorded in CORI: Barrett’s esophagus; esophageal inflammation (unless non-acid-related etiology); healed ulcer, duodenal, gastric or esophageal ulcer; stricture; and mucosal abnormality with erosion or ulcer.

RESULTS

Of 1569 patients, 16% had diabetes, 95% being type 2. Diabetic patients were significantly more likely to be male, older and have a higher body mass index, and less likely to report frequent heartburn and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. No significant differences were found in acid reflux and proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use between groups. In unadjusted analyses, diabetic patients had a similar risk for acid-related damage than non-diabetic patients (OR 1.09; 95% CI: 0.83, 1.42) which persisted after adjusting for gender, age, acid reflux, acid indication and PPI use (OR 1.04; 95% CI:0.79, 1.39).

CONCLUSIONS

No difference in risk of acid-related mucosal damage was found, even after adjustment for potential confounders. Our data do not support the need for a lower threshold to perform endoscopy in diabetic patients.

Keywords: Endoscopy, Diabetes, GERD

While research hints at an association between gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and diabetes [1,2], the evidence is inconsistent and the potential mechanism is not well defined. This is potentially of concern as the prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) is 7% of the United States population [3]. Moreover, insulin-dependent diabetic patients may have a higher prevalence of asymptomatic reflux based on 24-hour pH studies than the general population [2]. Given that asymptomatic esophagitis appears to be common among GERD patients [4], this becomes problematic as presumably these patients do not visit health care providers and thus remain untreated. This may occur more often in people with diabetes.

Studies evaluating the association between the presence of GERD and associated symptoms in patients with diabetic neuropathy have resulted in conflicting results, with one study suggesting that neuropathy may be an important factor for developing GERD symptoms in type 2 diabetes [1] and another observing no association between presence of acid reflux and neuropathy [5]. Other studies have suggested that diabetic patients may be more susceptible to acid injury [6,7] although these studies were small and did not utilize a control group.

It is difficult to determine the frequency of GERD-related disorders, such as erosive esophagitis, in a diabetic population, because the diabetic subjects may not present with typical symptoms to initiate an endoscopic evaluation. If there is a higher prevalence of undiagnosed GERD in these subjects due to the lack of symptoms and if diabetes is associated with more mucosal damage due to acid, then this could represent a very large under-diagnosed and treated population. To better quantify the risk of acid-related findings among patients with diabetes compared with non-diabetic patients undergoing EGD, we conducted a prospective study using the Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative (CORI), a national endoscopy database.

Methods

Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative (CORI)

We designed a cross sectional survey to determine the prevalence of GERD symptoms in diabetic patients undergoing upper endoscopy. Approval was granted by the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) Institutional Review Board (IRB) for conduct of the study (eIRB #3002). Each site participating in the study received approval from their local IRB. When a site lacked a local IRB, OHSU reviewed their application as an unaffiliated investigator, and agreed to provide oversight for subjects enrolled from that institution.

During the study period, the Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative (CORI) represented a consortium of 61 adult gastroenterology practices at 85 sites, including approximately 500 physicians in 24 states which utilize a computerized endoscopic procedure report generator to produce their endoscopic reports. Reports from each site are transmitted electronically to a central data repository and merged for analysis.

All sites contributing data to CORI were invited to participate in the study and were offered a small stipend of $250 for their participation. Recruitment occurred at 10 CORI sites located in the following cities: Portland, Oregon; Phoenix, Arizona; Denver, Colorado; Pinehurst, North Carolina; Santa Fe, New Mexico; Lincoln City, Oregon; Omaha, Nebrasaka; Silverdale, Washington. The sites used a pre-consent document to enable participation in research allowing patients undergoing endoscopy to give their consent to be contacted by a study investigator for any study for which they qualify, and participating sites were encouraged to offer this pre-consent to all patients undergoing EGD at their facility. The 10 sites were at 3 Veterans Affairs hospitals, 3 academic health care facilities and 4 community-based hospitals. The procedure volume at these sites represented 16% of EGD reported data in the CORI repository during the study period.

Data Collection

The study questionnaire was developed based on a validated questionnaire by Shaw et al. [8] asking about GERD symptoms. Questions on diabetic status, symptoms, medications, and sequela conditions (e.g. neuropathy, renal failure, and retinopathy) were added and piloted on 50 subjects before a final version was produced.

Potential participants were patients undergoing EGD between December 2006 and November 2007 as part of their routine care at a participating study center. Eligible participants undergoing an EGD provided pre-consent, were at least 18 years of age, and could complete the interview in English. We excluded patients whose indication for endoscopy was evaluation of suspected varices, surveillance of varices, screening for varices, variceal hemostasis, treatment of varices or feeding tube (PEG) placement. A program queried the CORI software at each local site to identify subjects meeting the entry criteria. Files were created, encrypted and sent via File Transfer Protocol (FTP) to CORI’s secured server machine.

Within 30 days after the EGD, the eligible subjects were contacted by telephone to seek their potential participation in the study. The study was described using an IRB-approved script and link to a webpage with further information. Once oral consent was given, patients were interviewed to provide demographic characteristics, height, weight, frequency and severity of acid-related symptoms including reflux, previous upper gastrointestinal disease, use of proton pump inhibitors and other current pain medication for the treatment of acid reflux, heartburn, arthritis, and inflammation. Body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) was calculated based on self-reported height and weight. Study data was collected directly into an electronic database and all identifying data was erased once the subject had participated. At one participating center, study subjects were required to also provide written consent. In these cases, the consent was mailed to the subject’s home for review and signature. If consent was not provided, data from the interview was not used.

We identified diabetic subjects from the patient interview and not from the CORI report. We defined diabetes by self-reported response to the questionnaire. Those who responded ‘yes’ to a question: ‘Do you have diabetes and have been on diabetic medication for greater than 3 months’, regardless of the type of diabetes, were considered as diabetic patients in this study. If a patient indicated the presence of diabetes, he or she was asked to provide further details including type, length of treatment, current diabetic medications, diabetes-related complications and diabetic control. To determine if patients experienced heartburn symptoms, we asked “Thinking about the past 3 months, did you have the following? Heartburn – A burning feeling rising from the stomach or lower part of the chest towards the neck”. If yes, we then asked patients to report the frequency of heartburn symptoms during the past 3 months giving them the option of ‘Did not have’, ‘Less than 1 day per week’, ‘1 day per week’, ‘2-3 days per week’, ‘4-5 days per week’, or ‘6-7 days per week’. We considered a patient to have heartburn if they answered ‘2-3 days per week’ or more.

Data from the CORI endoscopy report was available for each participant. The report is entered by the endoscopist immediately after the procedure and includes details on indications, findings and other procedure-related information. Participants were considered to have an acid-related finding if at least one of the following findings was entered on the CORI report: Endoscopist impression of Barrett’s esophagus, esophageal inflammation (unless etiology was not acid-related), healed ulcer, duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, esophageal ulcer, stricture, and mucosal abnormality with the sub-categorization of erosion and/or ulcer. Having an acid indication was defined by a positive response to the following indications in the CORI report: suspected, surveillance or screening for Barrett’s esophagus; dysphagia; reflux; and surveillance of gastric or duodenal ulcers.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using SAS v9.1 software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). For descriptive analysis of patient data, we used Pearson’s chi-square test or Exact tests (Fisher’s and Monte Carlo estimates) for categorical variables and one-way analysis of variance for continuous measures to examine variation in demographic and potential risk factors for acid-related findings. The relation of diabetes to risk of acid-related findings was quantified with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) obtained from multivariate logistic regression. Potential covariates in the model included age, gender, race/ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) use, histamine2 (H2) blocker use, self-reported acid reflux, self-reported heartburn, previous upper gastrointestinal disease, and any acid-related indication defined as any of the following indications listed on the CORI report: Barrett’s esophagus (suspected, surveillance, screening), dysphagia, reflux, surveillance of gastric or duodenal ulcer. We performed sensitivity analyses on our final model to determine if the definitions we used to characterize the endpoint and certain potential covariates were too broad and therefore obscured a potentially significant difference.

Results

During the study time period, 6386 EGDs were performed in 5837 unique patients at the study sites. Of the 2291 patients meeting the query inclusion data, 201 were not eligible. The reasons for ineligibility included: lacking a valid phone number (n=115), unable to speak on the phone due to hospitalization or illness (n=33), deceased (n=3), underwent emergency procedure (n=2), surgical removal of esophagus or stomach (n=3), do not speak English (n=7), did not recall providing pre-consent (n=13), did not undergo procedure (n=8), and subject name received in query outside study window time (n=17). When contacted for the study, 65 subjects refused to participate. From the site that required a written consent form, 25 were interviewed but did not return the consent form to allow the data into the study analysis. We were unable to reach 427 potential study subjects. A total of 1573 interviews were conducted but 4 were excluded because they occurred outside of the 30-day time window. The remaining 1569 subjects were included in the final analysis.

Among the 1569 subjects, 256 (16%) reported having diabetes. The prevalence of diabetes ranged from 8-22% across the 10 participating sites. The majority (95%) of diabetic patients were type 2. All patients in the diabetes group had an average of 9.5 years of treatment. Many diabetic patients (57%) reported having one or more diabetic complication of neuropathy, retinopathy, renal insufficiency or failure, with the prevalence of these conditions about 50% higher among those with type 1 disease.

Potential risk factors for acid-related findings varied by diabetic status as shown in Table 1. Diabetic patients were significantly more likely to be male (64.8% vs 54.5%; p=.01), older (mean age 62.9 vs 58.0 years; p<.0001) and have a higher body mass index (mean 31.2 vs 27.7; p<.0001) than non-diabetic patients. However, the prevalence of acid reflux reported by diabetic status was similar (70% vs 71%; p=.79) in each group. Diabetic patients were significantly less likely to experience frequent heartburn symptoms (defined as at least 2-3 times per week) compared with non-diabetic patients (21% vs 30%; p=.01). PPI use did not differ between the groups (56% in diabetic patients vs 55% in non-diabetic patients; p=.69) while those with diabetes were less likely to report NSAID use (11% vs 16%; p=.03).

Table 1.

Distribution at enrollment of demographic characteristics and possible risk factors for acid-related findings by diabetic status among 1569 men and women undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD).

| Diabetic Patients | Non-Diabetic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Patients | p-value | |||

| Gender | N | % | N | % | |

| Male | 166 | 64.8 | 716 | 54.6 | .00 |

| Female | 90 | 35.2 | 595 | 45.4 | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| < 50 | 31 | 12.1 | 331 | 25.3 | <.0001 |

| 50 – 59 | 66 | 25.8 | 238 | 26.6 | |

| 60 – 69 | 89 | 34.8 | 344 | 26.3 | |

| ≥ 70 | 70 | 27.3 | 286 | 21.9 | |

| Mean Age (SD) | 62.9 | (11.4) | 58.0 | (14.4) | <.0001 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 194 | 75.8 | 1105 | 84.2 | .00 |

| Black | 25 | 9.8 | 60 | 4.6 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2 | 0.8 | 7 | 0.5 | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native |

9 | 3.5 | 31 | 2.4 | |

| Multi-racial | 12 | 4.7 | 21 | 1.6 | |

| Hispanic (any race) | 14 | 5.5 | 73 | 5.6 | |

| Other/Refused | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 1.2 | |

| Height (in) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 67.8 | (4.0) | 67.7 | (3.9) | .48 |

| Weight (lbs) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 204.4 | (46.4) | 181.1 | (42.4) | <.0001 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) Categories |

|||||

| < 25 | 45 | 17.7 | 438 | 33.6 | <.0001 |

| 25 to < 30 | 75 | 29.5 | 470 | 36.0 | |

| ≥30 | 134 | 52.8 | 397 | 30.4 | |

| Body Mass Index Mean (SD) | 31.2 | (6.9) | 27.7 | (5.5) | <.0001 |

| Self-reported medical history | |||||

| Acid-reflux | 180 | 70.6 | 914 | 69.8 | 0.79 |

| Heartburn | 54 | 21.3 | 393 | 30.0 | .01 |

| Previous upper GI disease* | 126 | 51.0 | 576 | 44.8 | .07 |

| Any PPI† use | 144 | 56.3 | 721 | 54.9 | .69 |

| H2 Blocker‡ use | 20 | 7.8 | 117 | 8.9 | .57 |

| NSAID§ use | 27 | 10.6 | 208 | 15.8 | .03 |

SD = Standard deviation

Previous upper GI disease includes any one of the following: Gastroparesis, Peptic Ulcer disease, Gastritis, Esophagitis

PPI use includes any of the following: Lansoprazole, Omeprazole, Rabeprazole, Pantoprozole, Esomeprazole

H2 Blocker use includes any of the following: Famotidine, Nizatidine, Ranitidine, Cimetidine

NSAID use includes prescription and over the counter

Overall, acid-related findings were reported by the endoscopist for 690 (44.0%) participants (Table 2). The prevalence of acid-related findings did not differ by diabetic status (45.7% in diabetic patients vs 43.6% in non-diabetic patients; p=.54). Men were more likely than women to have an acid-related finding (51.7% vs 34.0%; p=<.0001). Increasing age, self-reported acid regurgitation and previous upper GI disease were also associated with acid-related findings.

Table 2.

Factors associated with acid-related findings among 1569 men and women undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD).

| Characteristic | Total N | Acid-related finding N (%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1569 | 690 (44.0) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 882 | 456 (51.7) | <.0001 |

| Female | 685 | 233 (34.0) | |

| Age | |||

| < 50 | 362 | 140 (38.7) | .04 |

| 50 – 59 | 414 | 176 (42.5) | |

| 60 – 69 | 433 | 200 (46.2) | |

| ≥ 70 | 356 | 173 (48.6) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | 1299 | 586 (45.1) | .18 (MC) |

| Black | 85 | 26 (30.6) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 9 | 4 (44.4) | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 40 | 17 (42.5) | |

| Multi-racial | 33 | 11 (33.3) | |

| Hispanic (any race) | 87 | 40 (46.0) | |

| Other | |||

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) Categories |

|||

| < 25 | 483 | 196 (40.6) | .12 |

| 25 to < 30 | 545 | 256 (47.0) | |

| ≥30 | 531 | 234 (44.1) | |

| Self-reported medical history | |||

| Diabetes | 256 | 117 (45.7) | .54 |

| Acid-reflux | 1094 | 510 (46.6) | .00 |

| Heartburn | 447 | 205 (45.9) | .36 |

| Previous upper GI disease* | 702 | 354 (50.4) | <.0001 |

| Any PPI† use | 865 | 376 (43.5) | .65 |

| H2 Blocker‡ use | 137 | 65 (47.5) | .39 |

| NSAID§ use | 235 | 113 (48.1) | .17 |

MC, computed using Monte Carlo estimate due to small cell sizes

Previous upper GI disease includes any one of the following: Gastroparesis, Peptic Ulcer disease, Gastritis, Esophagitis

PPI use includes any of the following: Lansoprazole, Omeprazole, Rabeprazole, Pantoprozole, Esomeprazole

H2 Blocker use includes any of the following: Famotidine, Nizatidine, Ranitidine, Cimetidine

NSAID use includes prescription and over the counter

The frequency of the individual findings that comprise the acid-related finding outcome is presented in Table 3. Patients with diabetes had a higher prevalence of mucosal abnormality with erosion or ulcer compared with non-diabetics (12.9% vs 8.8%; p=.04). No other statistical significance was observed between patients with and without diabetes for remaining individual acid-related findings.

Table 3.

Distribution and frequency of findings that comprise the outcome of any acid-related finding.

| Diabetic Patients N = 256 |

Non-Diabetic Patients N = 1313 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | p-value | |

| ANY ACID-RELATED FINDING |

117 | 45.7 | 573 | 43.6 | .54 |

| Individual Acid-Findings | |||||

| Any Barretts Esophagus | 34 | 13.3 | 169 | 12.9 | .86 |

| Healed Ulcer | 1 | 0.4 | 12 | 0.9 | .71 (F) |

| Stricture | 35 | 13.7 | 169 | 12.9 | .73 |

| Mucosal Abnormality (w/erosion or ulcer) |

33 | 12.9 | 116 | 8.8 | .04 |

| Esophageal, gastric or duodenal ulcer |

8 | 3.1 | 56 | 4.3 | .40 |

| Esophageal inflammation (acid-related) |

28 | 10.9 | 180 | 13.7 | .23 |

F, Fisher’s Exact test used to calculate p-value due to small cell sizes

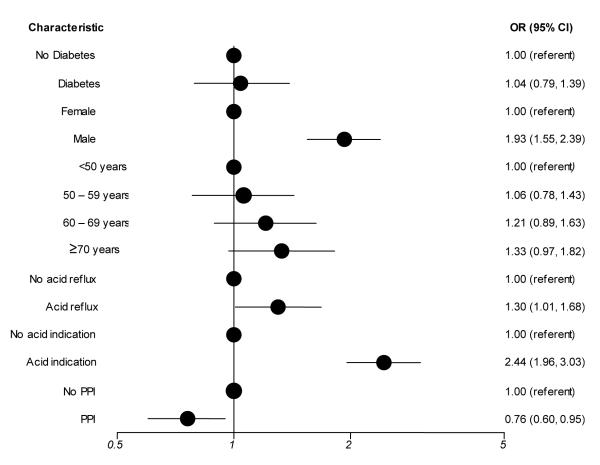

In multivariate analysis as shown in Figure 1, the risk for an acid-related finding was similar for diabetic patients compared with patients without diabetes (OR 1.04; 95% CI:0.79, 1.39). Age, gender, any acid-related indication and previous upper GI disease were also independent predictors for an acid-related finding. PPI use was associated with significantly reduced risk for an acid-realted finding (OR 0.76; 95% CI: 0.60, 0.95). Race/ethnicity was not found to be associated with acid-related findings and thus was not included in the final model.To examine whether the definitions for acid-related findings and acid-related indications was too broad, we narrowed the definitions to determine if excluding potential acid-related findings (healed ulcer, Barrett’s esophagus) and indications (dysphagia, individual and all Barrett’s esophagus indications) would produce a different association. We also examined diabaetic status as none, diabetic and diabetic with complications. None of these additional analyses produced different results.

Figure 1.

Relative risk of an acid-related finding among 1569 men and women undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD): results of a multivariate logistic regression analysis.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; black circle represents odds ratio;

Model adjusted for age (categorical), gender, self-reported presence of acid-reflux symptoms, PPI use, and any acid indication listed on the CORI report defined as suspected, surveillance or screening for Barretts esophagus; dysphagia; reflux; and surveillance of gastric or duodenal ulcers.

Discussion

Acid-related findings were common, with a prevalence of 44%, in this cohort of patients undergoing upper endoscopy. Although we hypothesized that there may be a discordance between acid-related symptoms and findings in patients with diabetes, we observed no difference in risk of acid-related findings for diabetic patients compared with non-diabetic patients after adjustment in multivariate models. This is at odds with previous reports that patients with diabetes may be more susceptible to acid-injury while experiencing fewer symptoms [6,7]. However, in our analysis, age confounded this relationship. While diabetic patients reported less heartburn symptoms than patients without diabetes, this disparity did not persist after adjusting for age. The prevalence of PPI use was high in both groups, which may lead to an underestimation of acid disease since healing would have occurred prior to endoscopy. The use of PPIs did not differ between groups and although it was protective for acid-related findings, it did not confound the risk in patients with diabetes, although we do not know the reasons PPIs were prescribed in each group.

The relationship between acid-related mucosal damage and diabetic status has not been well studied. In a small retrospective study of diabetic patients, Parkman et al. [6] found gastroparesis to be associated with esophagitis and other gastroduodenal abnormalities such as gastric ulcers and duodenal erosions. A more recent small study of Japanese diabetic patients reported the prevalence of reflux esophagitis at 17.6% in the diabetic group compared with 10.3% in sex and age-matched controls, although the difference was not statistically significant [9]. While suggestive of a relationship between diabetes and acid-related conditions, these studies were limited by small sample size and the lack of a control population, as well as the influence of diabetes severity, glycemic control, or complications on this possible association. In this study, we included both type 1 and 2 diabetic patients, although the majority (95%) were not insulin dependent. To ensure that diabetes type did not affect our results, we performed sensitivity analyses excluding type 1 patients from our logistic regression model and noted no difference in associations. Our study concurs with a small cross-sectional study by Nozu et al. [10], which reported no association in the prevalence of diabetes in patients with symptomatic and asymptomatic esophagitis diagnosed by upper endoscopy.

The severity of diabetes, as related to complications such as neuropathy resulting from poor glycemic control, is hypothesized to be associated with acid-related conditions. However in this study, we did not find an association between more severe diabetes (as measured by self-reported diabetic complications) and acid-related findings, both in our descriptive analyses and in our multivariate analysis.

We were mindful that the definitions we chose for our endpoint and potential covariates may have been too broad. We performed sensitivity analyses on our final model to determine if the definitions we used to characterize the endpoint and certain potential covariates were too extensive and therefore obscured a potentially significant difference. The outcome was revised to exclude Barretts esophagus and healed ulcer as well as the acid-related indication was revised to exclude Barretts esophagus surveillance, all indications of Barretts Esophagus and dysphagia. These modifications, both individually and together in the model, as well as exclusion of our acid-related indication variable did not alter the results for our exposure of interest, diabetic status, and thus we presented our original results using the more inclusive definitions.

This study does have several limitations. Use of the CORI population includes highly detailed information collected at the time of endoscopy using a format, which becomes part of the legal medical record. However, at interview we collected patient-reported information on symptoms, medication use, weight, height and diabetic history which may be biased by patient recall and understanding. On the other hand, this comprehensive collection of baseline information enabled us to evaluate the association between diabetes and acid-related findings on endoscopy while controlling for potential confounders.

The CORI consortium may not be representative of endoscopic practice in the United States. Physicians who participate in CORI are comfortable using computers to generate endoscopy reports and sharing data. However, in a recent analysis, we compared CORI data in patients age 65 and older with a Medicare dataset and found the CORI patients to be similar to the Medicare population receiving endoscopy [11]. A unique strength of this study is that data were accrued from diverse practice settings in different regions of the United States in order to examine diabetic patients across different populations, rather than restrict our patients to a particular population.

Patients with diabetes were over-represented in the cohort (16%) relative to the estimated prevalence of treated diabetic individuals in the United States (7%), suggesting they may be more likely than patients without diabetes to undergo EGD. The high prevalence of diabetic patients undergoing EGD was unexpected but certainly is indicative of the burden of disease in individuals receiving health care in the US. This is an important group to consider given the high prevalence of both diabetes and GERD in the US population. However, our data do not support the need for a lower threshold to perform endoscopy in diabetic patients.

Acknowledgements

Grant Support and Disclosure: This project was supported with funding from NIDDK UO1 DK57132 and AstraZeneca. In addition, the practice network (Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative) has received support from the following entities to support the infrastructure of the practice-based network: AstraZeneca, Bard International, Pentax USA, ProVation, Endosoft, GIVEN Imaging, and Ethicon.

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. Linda Koo for her contribution to the study design.

Footnotes

Dr. Eisen is the co-director of the Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative (CORI), a non-profit organization that receives funding from federal and industry sources. The CORI database is used in this study. This potential conflict of interest has been reviewed and managed by the OHSU and Portland VAMC Conflict of Interest in Research Committee. Dr. Eisen had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis

Dr. Silberg is employed by AstraZeneca.

References

- 1.Wang X, Ptchumoni CS, Chandrarana K, Shah N. Increased prevalence of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux diseases in type 2 diabetics with neuropathy. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(5):709–12. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lluch I, Ascaso JF, Mora F, Minguez M, Pena A, Hernandez A, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux in diabetes mellitus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(4):919–924. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.987_j.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National diabetes fact sheet: general information and national estimates on diabetes in the United States. 2007 Available from http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2007.pdf.

- 4.El-Serag HB, Peterson NJ, Carter J, Graham DY, Ricahrdson P, Genta RM, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux among different racial groups in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1692–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray FE, Lombard MG, Ashe J, Lynch D, Drury MI, O’Moore B, et al. Esophageal function in diabetes mellitus with special reference to acid studies and relationship to peripheral neuropathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82(9):840–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parkman HP, Schwartz SS. Esophagitis and gastroduodenal disorders associated with diabetic gastroparesis. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1477–1480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boehme MWJ, Autschbach F, Ell C, Raeth U. Prevalence of silent gastric ulcer, erosions or severe acute gastritis in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus – A cross-sectional study. Hepato Gastroenterology. 2007;54(74):643–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw MJ, Beebe TJ, Adlis SA, Talley NJ. Reliability and validity of the digestive health status instrument in samples of community, primary care, and gastroenterology patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15(7):981–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ariizumi K, Koike T, Ohara S, Inomata Y, Abe Y, Iijima K, Imatani A, Oka T, Shimosegawa T. Incidence of reflux esophagitis and H pylori infection in diabetic patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(20):3212–7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nozu T, Komiyama H. Clinical characteristics of asymptomatic esophagitis. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(1):27–31. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2120-2. Epub 2008 Feb 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sonnenberg A, Amorosi SL, Lacey MJ, Lieberman DA. Patterns of endoscopy in the United States: analysis of data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the National Endoscopic Database. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67(3):489–96. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.08.041. Epub 2008 Jan 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]