Abstract

Statutes on psychiatric advance directives (PADs) allow competent individuals to document instructions for future mental health treatment in the event of an incapacitating crisis. PADs are aimed at promoting a stronger sense of patient self-determination, considered a central tenet of psychosocial rehabilitation and recovery; however, it is unknown what factors (if any) lead psychiatric patients with PADs to experience this benefit long term. The current study involves examination of 1 year effects on perceived treatment self-determination among 125 people with mental disorders who completed PADs via a 1-on-1 facilitated PAD intervention. Descriptive analyses showed participants documented medically relevant information that would assist doctors in a crisis and participants reported a high level of satisfaction with the facilitated PAD intervention. Multivariate analyses demonstrated that increased sense of autonomy at 1 year was predicted by race, understanding PADs, and verbal memory. Results provide useful guidance for administrators and clinicians, suggesting that PADs show promise in helping empower people with mental illness, especially African-American clients. Further, findings indicate that optimal implementation of PADs will be achieved when facilitated intervention assists people with mental illness to better understand what PADs are and to remember they have a PAD at the time they are experiencing a psychiatric crisis.

Keywords: psychiatric advance directives, patient self-determination, psychiatric disabilities, mental health law, psychosocial rehabilitation

Legislation aiming to promote advance care planning and treatment self-determination among people with mental illness has proliferated in recent years. In the United States, laws defining psychiatric advance directives (PADs) have been passed in 25 states, allowing competent persons to document advance instructions for their future mental health treatment or to designate a health care agent to make decisions for them, in the event of an incapacitating psychiatric crisis (Appelbaum, 2004; Srebnik & La Fond, 1999; Swanson, Swartz, Ferron, Elbogen, & Van Dorn, 2006). In addition to recognizing the potential benefits of PADs, many states are beginning to recognize legal obligations under the federal Patient Self-Determination Act of 1991, which includes informing all hospital patients that they have a right to prepare advance directives and—with certain caveats—that clinicians are obliged to follow these directives (Hoge, 1994). As such, federal law helps ensure that people with mental illness, in whatever state they live, can use medical advance directives to specify mental health treatment preferences or to assign proxy decision makers for mental health decisions.

If followed by treatment providers, PADs can help patients gain better access to the types of treatment that work best for them, especially during times when they are most in need of care but least able to speak for themselves (Backlar, McFarland, Swanson, & Mahler, 2001; Joshi, 2003; Vuckovich, 2003). Further, the very exercise of preparing a PAD and discussing it with a mental health professional may enhance therapeutic alliance and improve treatment engagement (Atkinson & Garner, 2003; Srebnik, 2004; Swanson, Swartz, Elbogen et al., 2006). In theory, PADs provide a transportable document—increasingly accessible through electronic directories—to convey information about a patient’s treatment history, including medical disorders, emergency contact information, and medication side effects (Swartz, Swanson, & Elbogen, 2004). Clinicians often have limited information about psychiatric patients who present in crisis centers or hospital emergency departments (Elbogen, Tomkins, Pothuloori, & Scalora, 2003). Nonetheless, these are the typical settings in which clinicians are called on to make critical management and treatment decisions with whatever limited data may be available. With PADs, clinicians could gain immediate access to relevant information about individual cases and thus improve the quality of clinical decision making.

A large-scale, randomized clinical trial indicated that a manualized PAD facilitation helps overcome patient barriers to completing PADs and helps improve working alliance and treatment engagement among people with severe mental illness (Swanson, Swartz, Elbogen et al., 2006). The authors of that study found that 61% of participants in the facilitated session completed an advance directive or authorized a proxy decision maker, compared with only 3% of control group participants. At follow-up, participants in the facilitated session had a greater working alliance with their clinicians and were more likely than were those in the control group to perceive that they were receiving the mental health services they needed. Another analysis from this clinical trial involved examining competence to complete PADs with a newly developed instrument that evaluates patients’ understanding, appreciation, and reasoning ability applied to PADs and to specific treatment decisions contained in PADs (Elbogen et al., 2007). Elbogen et al. (2007) found the manualized PAD facilitation significantly improved patients’ competence to complete PADs, as well as patients’ treatment decision-making capacity in general. The PAD facilitation intervention most dramatically increased treatment decision-making competency among patients with low cognitive functioning.

For these reasons, researchers, clinicians, and consumer-advocates have hypothesized that patients who write PADs will experience a greater sense of self-determination with respect to their mental health care (Backlar et al., 2001; Srebnik, 2004; Swanson, Tepper, Backlar, & Swartz, 2000). People with a PAD may thus feel their treatment is more self-determined because they are now actively coauthoring their own mental health crisis plans. In particular, empirical research supports the notion that when patients are free to express their preferences in the context of treatment, they perceive that their treatment is more under their control and then take greater responsibility for that treatment (Lecomte, Wallace, Perreault, & Caron, 2005; Ryan & Deci, 2000; Williams, Rodin, Ryan, Grolnick, & Deci, 1998). Research on psychiatric rehabilitation supports the benefits of helping empower people with mental illness to become more autonomous, to take a greater role in their own care, and to actively participate in their own lives (Anthony, 1998; Liberman, 1992; Spaulding, Sullivan, & Poland, 2003). As such, PADs can be tools to help instill a stronger sense of empowerment and autonomy among people with mental illness, both of which are central to recovery and rehabilitation.

However, PADs are not written in a vacuum, and a number of factors might reduce the effects on patient’s perceived self-determination. Research has shown that many patients report not understanding how PADs work, due to lack of experience with new laws, difficulty understanding abstract concepts of cognitive and feeling states in the future, and other cognitive limitations (Swanson et al., 2003). Further, many clinicians report barriers to PADs, including not having easy access to them (Van Dorn et al., 2006) and not being familiar with the laws in the first place (Elbogen et al., 2006). Currently, it is unknown which key features of PADs allow PAD completers to have long-term benefits from the process. Given the realities of poorly responsive and fragmented mental health care systems that patients often must contend with, merely having a PAD may do little, in the long run, to help patients gain more control over their treatment.

Without more information about what promotes, or hinders, these types of outcomes, administrators and clinicians lack guidance about how to effectively implement laws on PADs. As described above, published studies have examined the outcomes associated with PADs; however, relatively less attention has been devoted to empirically examining the process by which PADs lead to these outcomes (arguably, the latter is especially needed to determine the approach that ought to be taken when applying PADs in practice). In other words, how should PADs be completed to assure that patients experience an increased sense of autonomy in the long term? Does the content of what is written in the PAD matter? If so, in what ways? How does a patient’s understanding of PADs influence these long-term outcomes associated with writing a PAD? Perhaps a consumer who better understands the impact of PADs on his or her life will maintain longer term perception of self-determination after completing a PAD. Or, are more global clinical or demographic characteristics associated with benefits resulting from PADs? What factors contribute to better outcomes among those with PADs? The purpose of this article is to address these questions and to investigate what predicts long-term perceptions of self-determination among people with mental disorders who have completed PADs. The results therefore point policy makers and mental health professionals to specific ways to implement PADs, so that patients gain optimal benefit.

Method

Sample

The primary target for PADs is the population of individuals who experience fluctuating decisional capacity often associated with psychotic symptoms. The current study focuses on a subset from a larger project on PADs (Swanson, Swartz, Elbogen et al., 2006), and the study’s sampling criteria were individuals who were age 18–65 years; who had a chart diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizo-affective disorder, other psychotic disorder, or major mood disorder with psychotic features; and who were receiving community-based treatment provided through one of two area programs in the state mental health system of North Carolina.

The two community mental health programs provided comprehensive de-identified lists of clients prescreened for study eligibility criteria. From these lists, a random sample of client cases was screened. Sequential admissions from these programs to the regional state psychiatric hospital were also screened. Treating clinicians verified that the identified patient met study selection criteria and approached the patient initially for permission have a researcher contact them. Patients willing to be contacted were then approached by a research interviewer to obtain informed consent and to conduct the baseline interview. Of those approached, 8% refused to participate but did not differ from those who ultimately consented in terms of gender, ethnicity, or diagnosis.

The subset for this analysis included 125 participants who met the above study criteria, provided both baseline and 1 year data, and completed a PAD via a one-on-one facilitated intervention. These participants are the only known group of people with mental illness involved in a research study and who have had a PAD for at least 1 year, offering the opportunity to systematically investigate the long-term effects of PADs among those who have completed these legal documents. Using this sample also allows study of perceptions of the facilitated psychiatric advance directive (F-PAD) intervention process, which has not yet, to our knowledge, been studied.

Procedure

All participants in this subgroup provided data at baseline and at 1 year, as described in the measures below. All participants in the current study also completed the F-PAD within 2 months of the baseline interview. The F-PAD was designed as a structured but flexible session to provide orientation to PADs, as well as to provide direct assistance that may be necessary for patients with mental illness to complete a legal PAD. The F-PAD focused on the requirements for PADs in North Carolina law, following the forms promulgated in these statutes. The F-PAD reviewed past treatment experiences and educated participants about writing an advance instruction and designating proxy decision makers. If participants wished to prepare a PAD, the facilitator provided assistance in doing so by eliciting preferences and advance consent or refusal for psychotropic medications, hospital treatment, or electroconvulsive therapy, and gathering information about crisis symptoms, relapse and protective factors, and instructions for inpatient staff (e.g., effective strategies to avoid use of seclusion and restraints).

As part of the F-PAD process, facilitators asked open-ended questions about participants’ preferences, and facilitators clarified unclear preferences. In the event the participant wished to document a request unlikely to be followed (e.g., “I want to smoke in the emergency room.”), the facilitator would provide some feasibility testing (e.g., “I don’t think the hospital policy would allow you to smoke in the emergency room.”). At this point the participant could either not document the preference (e.g., “You’re right, there’s no way they’d let me smoke in the emergency room.”) or write it down in the PAD anyway (e.g., “I realize that but I want doctors to know how important my smokes are.”). Thus, although the F-PAD intervention prompted participants to assess the feasibility and appropriateness of PAD instructions, it strictly supported participants’ preferences in recording any instructions they wished. As such, the F-PAD intervention does not aim to change the substance of the patient’s preferences or directives; instead, it helps patients clarify their instructions and the reasons underlying them. F-PAD facilitators made intentional effort to never use leading questions that might influence participants’ stated instructions.

Finally, assistance was provided to draft the PAD document, obtain witnesses, obtain notarization, ensure that the PAD was recorded in the participant’s medical record, and, if desired, register the PAD with a national or state electronic registry. Participants who consented to storing their advance care documents with an electronic registry received an identifying sticker to affix to their identification card and/or driver’s license, to carry on their person at all times. The F-PAD program offered participants a bracelet or laminated card, to carry at all times, which noted that he or she had a PAD and which indicated the proxy decision maker’s name if applicable, the case manager’s name, the emergency contact information, and the toll-free telephone number of the relevant registry. Completing a PAD via the F-PAD intervention involved, on average, 2 hours. The F-PAD was conducted by six trained research assistants, one with a master’s degree and the others with bachelor’s degrees, each of whom obtained a high level of fidelity throughout the study period (for details, see Elbogen et al., 2007; Swanson, Swartz, Elbogen, et al., 2006).

Measures

Demographic and clinical data

Demographic and clinical data were obtained at baseline. Demographic variables included age, education, ethnicity, and gender. The anchored version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) was used to assess current psychiatric symptoms (Moerner, Mannuzza, & Kane, 1988). The Insight and Treatment Attitudes Questionnaire (ITAQ) was used to measure awareness of mental health problems and acknowledgment of need for treatment in the past, at the current time, and in the future (McEvoy, Apperson, Appelbaum, & Ortlip, 1989). Additional clinical variables included diagnosis as obtained from the participant’s medical record.

Neurocognitive functioning

Neurocognitive functioning was tested at baseline with the American National Reading Test (AMNART), which asks participants to read a list of words that become progressively more advanced, to estimate premorbid verbal IQ (Blair & Spreen, 1989) and the Hopkins Verbal Learning Task (HVLT), which taps into delayed memory by having a list of 12 words read to participants three times and having participants be asked what they remember after each repetition and again after 30 minutes (Brandt, 1991).

PAD content

All participants in this analysis completed PADs within 2 months of the baseline interview. Content from these PAD documents was coded by four research assistants. To ensure reliability in coding, research assistants each coded the same three charts initially to measure interrater reliability. Research assistants obtained kappas ranging from .75 to .90 and were deemed able to code charts individually. Coding paralleled the main categories of information found in the North Carolina PAD statute. These included (a) crisis symptoms; (b) medications consented to or refused; (c) hospitals consented to or refused; (d) emergency contact information; (e) relapse risk factors; (f) protective factors; (g) instructions to hospital staff; (h) electroconvulsive therapy preferences; (i) other instructions and/or medical information on side effects or allergies to medications.

F-PAD intervention process

Data was collected, at 1 year, about patients’ experiences with the F-PAD intervention, including questions about consumers’ satisfaction with the F-PAD, consumers’ perceptions of whether they could have written a PAD without the F-PAD, consumers’ knowledge about whether their PAD was sent by the F-PAD facilitator to the consumers’ medical records, and consumers’ overall opinion about whether they found the F-PAD helpful.

Comprehension of PADs

Comprehension of PADs was measured at 1 year with the Decisional Competence Assessment Tool for Psychiatric Advance Directives (DCAT-PAD), which was developed to mirror the structure of the MacArthur Competency Assessment Tool for Treatment (MacCAT-T; Grisso, Appelbaum, Mulvey, & Fletcher, 1995; Srebnik, Appelbaum, & Russo, 2004) and which evaluates participants’ ability to understand basic elements of PADs (e.g., “A PAD involves a legal document to state my treatment preferences if I have a psychiatric crisis.”) and to reason about how PADs would specifically affect their lives and/or treatment (e.g., “With a PAD, I could say in advance I want doctors to give me Risperdol.”). The psychometric properties of these domains of the DCAT-PAD, indicating good internal consistency (α = .80), are described elsewhere (Elbogen et al., 2007).

Psychiatric hospitalization

Psychiatric hospitalization data was collected, at 1 year, regarding whether the patient had been admitted to a psychiatric hospital during the study period.

Perceived treatment self-determination

Perceived treatment self-determination was measured at both baseline and at 1 year, with a subset of items drawn from the Treatment Motivation Questionnaire (TMQ), an instrument developed with the conceptual framework of Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000), which measures a construct termed intrinsic motivation that denotes reasons for engaging in treatment based on patient choice. The TMQ items include the following: “I am responsible for this choice of treatment,” “I really want to make some changes in my life,” “If I remain in treatment, it will probably be because I feel like it’s the best way to help myself,” “I decided to come to treatment because I was interested in getting help,” “I accept the fact that I need some help and support from others to beat my problem,” and “I chose this treatment because I think it is an opportunity for change.” Each item was scored on a 7-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The TMQ was adapted and was used to ask participants to focus on their mental health treatment specifically. For the current sample at baseline, these items showed good internal consistency (α = .78) and reliably tapped into a single construct of intrinsic motivation. In the current analysis, scores from these items were summed to create a total score representing perceived self-determination.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics on the 125 participants who completed PADs were used to obtain baseline frequencies, measures of central tendency, dispersion on perceived self-determination, PAD comprehension, demographic variables, clinical characteristics, cognitive functioning, PAD content, and perceptions of F-PAD intervention with SAS version 9.1. Specific examples of PAD content are presented as qualitative data to illustrate what participants wrote in their PADs that related to different areas of the PAD document. Raw scores from all cognitive tests were converted to standardized scores based on available normative samples and corrected for age and education (Blair & Spreen, 1989; Brandt, 1991; Wechsler, 1997).

We then examined which factors led to superior perceived self-determination at 12 months. Given power considerations, stepwise linear regression analyses were used, in which independent variables were excluded from subsequent analyses if they did not meet a probability level of .10. With this procedure, 12 month perceived self-determination was regressed on demographic, clinical, and neurocognitive variables as well as on PAD content and perceptions of F-PAD process variables, with baseline perceived self-determination controlled for.

Results

At baseline, the average age of participants was 44.8 years (SD = 10.1 years). The sample was demographically representative of the public mental health system in North Carolina: 59% women and 41% men, 56% African-American, and 44% Caucasian. Only 12% were married or cohabiting, and 24% of the sample had less than a high school education. Clinically, 61% of participants had a chart diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, and 39% had bipolar disorder or depression with psychotic features.

BPRS mean scores also indicated mild–moderate symptomatology (M = 32.3, SD = 8.6). The sample showed a relatively high mean score at baseline on the ITAQ (M = 18.1, SD = 4.1), indicating high awareness of illness. The sample had premorbid verbal IQ estimates with scores that would be considered similar to the general population (M = 101.6, SD = 10.7). Similarly, the Hopkins domains, transformed into standardized T scores, showed low average verbal memory relative to the general population (M = 33.7, SD = 12.9). Mean scores on DCAT-PAD understanding and reasoning were in the average range compared with normative data on people with severe mental illness (Elbogen et al., 2007). With respect to perceived self-determination in mental health care, participants showed that generally equal distribution of change over the course of the year, with 34% having better intrinsic motivation scores on the TMQ at 12 months, 43% having lower scores at 12 months, and 23% the same scores at 12 months, compared with baseline scores on this measure.

Descriptive analyses were used to present PAD content as shown in Table 1. The majority of participants who completed PADs listed at least 3 crisis symptoms and protective factors, consented to and refused at least one psychotropic medication, prescribed strategies to reduce seclusion and restraints, and refused electroconvulsive therapy under any circumstance. About one fifth listed aggressive behavior and one fourth listed self-harm or suicidal ideation as particular crisis symptoms for doctors to be alerted to. Of the participants, 16% indicated medical problems that they wanted inpatient clinicians to be aware of because the problems could bear on the participants’ mental health treatment.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics on PAD Completers Retained at 1 Year

| Characteristics of PAD completers | % | n |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| African-American | 56 | 70 |

| Caucasian | 44 | 55 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 41 | 51 |

| Female | 59 | 74 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 24 | 30 |

| High school graduate or more | 76 | 95 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Psychotic disorder (schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder) | 61 | 76 |

| Affective disorder (bipolar disorder/major depression) | 39 | 49 |

| Psychiatric hospitalization | ||

| Was admitted to hospital during 1 year study period | 18 | 23 |

| Stayed out of the hospital during 1 year study period | 82 | 102 |

| Perceptions of F-PAD intervention | ||

| Endorsed being unable to do a PAD without F-PAD | 94 | 118 |

| Knew that F-PAD facilitator filed PAD in medical charts | 97 | 121 |

| Endorsed satisfaction with final draft of PAD created in F-PAD | 78 | 98 |

| Indicated the F-PAD was helpful for psychiatric crisis planning | 100 | 125 |

| Content of PAD documents | ||

| Listed 3 or more crisis symptoms | 79 | 98 |

| Consented to at least 1 specific psychotropic medication | 88 | 110 |

| Refused at least 1 specific psychotropic medication | 71 | 89 |

| Refused all psychotropic medications | 0 | 0 |

| Prescribed at least 1 strategy to reduce restraints/seclusion | 53 | 66 |

| Listed 3 or more protective factors | 60 | 75 |

| Refused ECT under any circumstance | 58 | 72 |

| Listed aggression among crisis symptoms | 18 | 23 |

| Listed self-harm or suicidal ideation among crisis symptoms | 26 | 33 |

| Listed medical problem that impacts behavior/mental health | 16 | 20 |

Note. N = 125. PAD = psychiatric advance directive; F-PAD = facilitated psychiatric advance directive; ECT = electroconvulsive therapy.

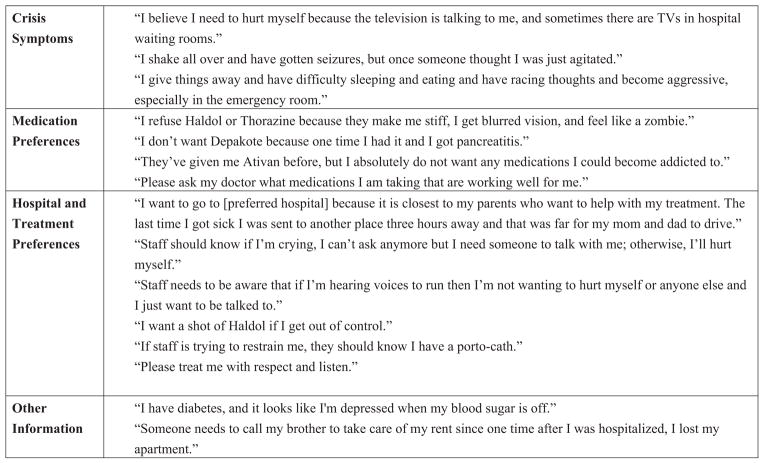

Figure 1 helps clarify specific instructions and preferences listed by subjects who completed PADs. In general, several themes emerge when viewing the data qualitatively, and they clarify the quantitative data in a number of ways. First, the data reveal that rather than consent to a specific medication, at least some subjects preferred to have future inpatient doctors confer with subjects’ outpatient doctors to check what medications were working well. Second, the PAD content shows that subjects not only expressed treatment preferences in their PADs but were able to and interested in listing the reasons behind these choices. Third, the data indicate that patients explicitly wanted inpatient staff to treat them with respect and, in many cases, gave specific instructions about how staff could do so. Fourth, subjects’ PAD preferences show that participants wanted not only to select medications or hospitals but also to convey additional details about medications side effects of comorbid medical problems, so that overall medical care would be improved.

Figure 1.

Examples of content from study PAD documents.

These PADs were created after the individualized F-PAD intervention, and after 1 year, the overwhelming majority of subjects had favorable views of the F-PAD. Over 90% indicated they could not have completed the PAD without the intervention, that the F-PAD enhanced their crisis planning, and that they knew that their PADs were stored and filed in their medical records. Most participants (78%) were satisfied with their PADs after 1 year. It should be noted that the other subjects who said they were not satisfied with their PAD were provided with an opportunity to change their PADs after the study ended.

Multivariate analyses were conducted to determine factors predicting increased perceived self-determination in this sample (Table 2). As expected, baseline perceived self-determination significantly predicted 12-month perceived self-determination (β = .59, p < .0001). Controlling for this, three variables emerged in the final model as significantly predicting 1 year perceived self-determination: being African-American (β = .22, p = .003), scoring on DCAT-PAD Reasoning (β = .15, p = .04), and scoring on Hopkins Delayed Recall (β = .16, p = .03) The model was statistically significant, F(4, 120) = 21.60, p < .0001, and accounted for a little less than half the variance in 12 month perceived self-determination (R2 = .43).

Table 2.

Predictors of 12 Month Perceived Self-Determination Among PAD Completers, Stepwise Linear Regression

| Source and predictor | df | M2 | β | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | |||||

| Model | 4 | 2734.55 | 21.60 | <.0001 | |

| Error | 116 | 3671.33 | |||

| Corrected total | 120 | 6405.88 | |||

| Predictor | |||||

| Baseline perceived self-determination | 1 | .59 | 8.24 | <.0001 | |

| Race; 0 = Causasian; 1 = African-American | 1 | .22 | 3.04 | .003 | |

| DCAT-PAD reasoning | 1 | .15 | 2.04 | .04 | |

| Hopkins Delayed Recall | 1 | .16 | 2.15 | .03 |

Note. R2 = .43. The following variables were eliminated from the final multivariate model as nonsignificant: age, gender, education, psychiatric symptoms (Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale), insight into disorder (Insight and Treatment Attitudes Questionnaire), IQ (American National Reading Test), diagnosis, psychiatric hospitalization, PAD content, and perceptions of F-PAD intervention. PAD = psychiatric advance directive; DCAT-PAD = Decisional Competence Assessment Tool for Psychiatric Advance Directive; F-PAD = facilitated psychiatric advance directive.

Discussion

In sum, the data showed that people with mental illness who completed PADs documented medically relevant information that would assist doctors if those people were to have a crisis. To illustrate, some patients listed medical conditions (e.g., diabetes) that could be masked by overt mental health symptoms (e.g., depression). No subject refused all medications, although most refused at least one type. Additionally, subjects reported a high level of satisfaction with the facilitated PAD intervention. In particular, nearly all the subjects reported they would have had difficulty completing a PAD on their own without assistance. With respect to long-term perceived self-determination, multivariate analyses showed that increased sense of autonomy at 1 year was predicted by ethnicity, by understanding PADs, and by better verbal memory among people with mental illness who completed PADs.

The data confirm other studies showing that what people write in PADs would be useful for clinicians in crisis situations (Srebnik et al., 2005). This expands on findings that people with mental illness generally document information in PADs consistent with community practice standards (Swanson, Swartz, Elbogen et al., 2006), by describing in greater detail the specific types of information people write in their PADs. In particular, Figure 1 illustrates the diversity of preferences written by showing how some preferences may be quite the opposite of others; for instance, many patients refused Haldol, but a number of patients requested Haldol if they felt out of control. Further, presenting the actual PAD content shows the usefulness of not just listing medications one refuses but also listing reasons behind these choices. Because the emergency room clinician sees only a small slice of a patient’s life, a slice when the patient may be psychotic, it is extremely useful for a patient to include the rationale for choices so that the emergency room clinician sees a larger scope of who the patient is and how they think about their preferences. Recent research suggests that when clinicians are aware of medically appropriate reasons for a medication refusal, clinicians are more likely to honor patient’s choices in a PAD (Wilder, Elbogen, Swanson, Swartz, & Van Dorn, 2007).

The current results provide useful guidance for administrators and clinicians in several ways. First, the data are the first report on consumers’ perceptions of the F-PAD process, informative for anyone developing PAD policy and procedures. The vast majority of subjects were satisfied with their final PAD document almost 1 year after the fact, which attests to the ability of the facilitation to capture a consumer’s genuine treatment preferences. Even more striking was the overwhelming endorsement of the usefulness of and the need for the F-PAD intervention, without which almost every subject said they would never have been able to get a PAD. This finding is consistent with an earlier report showing that people randomized to the F-PAD condition were over 20 times more likely to have a PAD at 2 months than were people who received no one-on-one assistance writing a PAD (Swanson, Swartz, Elbogen et al., 2006). For this reason, the subjects’ opinions about the F-PAD speak to how people with mental illness would probably hope for PADs to be implemented; specifically that a facilitator would assist the patient with the process. That 100% of participants thought the F-PAD intervention was helpful for psychiatric crisis planning suggests that the facilitation itself play a central role in effective implementation of PADs, underscoring the need to supplement mental health services provision with trained PAD facilitators if serious attempts to use PADs in practice are being considered.

Second, the findings indicate that PAD comprehension is central to achieving benefits from PADs (Srebnik et al., 2004; Swanson et al., 2003) because PADs require the ability to grasp somewhat difficult and abstract concepts, such as fluctuating decisional capacity and future preferences for treatment. In particular, because patients who better understood exactly how PADs would affect their lives and treatment demonstrated a higher level of perceived self-determination at 1 year, this suggests that some patients who complete PADs, even with the facilitation, may still not fully understand how they would be used to help their crisis planning. Thus, to bolster perceived autonomy, additional efforts may be needed to supplement PAD completion with focused teaching about how PADs would be used and what affects they would have on patient’s psychiatric treatment. Either through role playing, didactic education, or focused inquiry, it seems that ensuring people can visualize exactly how a PAD would work in a crisis would be linked to a greater sense of autonomy in the long term.

Third, and related, is the finding that verbal memory predicted perceived self-determination at 1 year among PAD completers. This finding was somewhat surprising because, prima facie, it is unclear why a cognitive function itself would be associated with increased experience of autonomy. But in the context of one’s having written a PAD, the result makes more sense; specifically, if the PAD involves a physical document that one needs to remember that one has, then a person with mental illness who has poorer verbal memory may be more at risk of forgetting that he or she has a PAD in the first place, especially if he or she is in the middle of experiencing a psychiatric crisis. Thus, this finding reveals the potential for people with PADs to be hospitalized and to not ever bring the PAD to their doctor’s attention. Hospitals’ inquiries into PADs is unknown, but to the extent this mirrors inquiry into medical advance directives, policies are not consistently implemented. And even if they were, the data imply that some patients with mental illness or cognitive impairments may not recall that they have one at the very moment it is most needed.

As a result, the data point to a potential weak point in implementing PADs; namely, a patient telling a doctor he or she has a PAD. Although some role play of this interaction may be useful to include in a facilitated PAD intervention, additional systemic steps are needed to increase chances a patient’s PAD gets on the radar. These might include filing PADs in multiple health settings, wearing bracelets alerting doctors a patient has a PAD, and having one’s PAD put on a portable thumb drive. Systemic interventions to increase recall could involve hospitals developing more sophisticated electronic medical records systems to alert clinicians that a patient has a PAD on file.

Fourth, the strongest predictor of 12-month perceived self-determination was race; being African-American was significantly related to an increased sense of autonomy at the end of the study period, even after clinical, demographic, cognitive, and PAD-related variables were controlled. Post hoc analyses indicated that there were no baseline differences on perceived self-determination between African-American and other subjects in the current sample and that ethnicity did not predict increased perceived self-determination at 1 year among people with mental illness in the larger study who had not written a PAD (neither did PAD reasoning or verbal memory, for that matter). That ethnicity remained significant in multivariate modeling for PAD completers provides preliminary evidence that writing these legal documents meant something important to this subgroup of patients. This corresponds to other findings on PADs and suggests that there is much greater demand for PADs among people with mental illness from racial minorities (Swanson, Swartz, Ferron et al., 2006).

Mental health consumers who are members of disadvantaged or marginalized social groups, or who feel deprived of personal autonomy in their choices, may value PADs more insofar as PADs are promoted as instruments to empower personal choice and self-determination in mental health treatment, that is, as a potential remedy for disempowerment. Instruments like PADs that promote perceived self-determination may encourage better treatment engagement and stronger therapeutic alliance (Berk, Berk, & Castle, 2004; Rosen, Ryan, & Rigsby, 2002; Ryan, Plant, & O’Malley, 1995; Williams et al., 1998; Zygmunt, Olfson, Boyer, & Mechanic, 2002). To the extent that research has shown that racial minorities often perceive more barriers to mental health care, PADs may prove to be a valuable tool to help racial minority patients with mental illness participate more actively in their treatment and take steps to achieving recovery.

There are several limitations in the current study. First, we examined participants’ perceptions of self-determined care but did not examine actual care received because there were so few people whose PADs could have been executed due to having been hospitalized. Thus, in the current analysis, we could not examine whether the F-PAD led to more care or to better quality care; we restricted analysis to whether participants thought that their mental health care was self-directed and self-chosen. Also, we did not examine whether patients received the crisis care they requested for periods of decisional incapacity in the PAD because few had such a crisis during the course of the year. In addition, awareness of PADs by clinicians and law enforcement remains low, reducing use of PADs in crises. Efforts are needed to gain buy-in from these stakeholders to ensure PADs are implemented in emergencies.

In conclusion, PADs are aimed at helping people with psychiatric disorders determine their own mental health care. The current study demonstrates that people with mental illness are able to document medically relevant information and that people who complete PADs report a high level of satisfaction with a facilitated, one-on-one PAD intervention. Multivariate analyses suggest that PADs may help empower people with mental illness among racial minorities and that optimal implementation of PADs can be achieved when a facilitated intervention assists people with mental illness better understand what PADs are and remember that they have PADs if they are experiencing a psychiatric crisis. The current findings show promise of a legal intervention to help people with mental illness move toward directing their own care and, ultimately, their own lives.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health research Grant R01-MH063949 and Independent Research Scientist Career Award K02-MH67864 awarded to Jeffrey W. Swanson. The study was also supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Mandated Community Treatment.

Contributor Information

Eric B. Elbogen, Forensic Psychiatry Program and Clinic, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine

Richard Van Dorn, College of Social Work, Justice, and Public Affairs, Florida International University.

Jeffrey W. Swanson, Department of Psychiatry, Duke University Medical Center

Marvin S. Swartz, Department of Psychiatry, Duke University Medical Center

Joelle Ferron, Department of Psychiatry, Dartmouth Medical School.

H. Ryan Wagner, Department of Psychiatry, Duke University Medical Center.

Christine Wilder, Department of Psychiatry, Duke University Medical Center.

References

- Anthony WA. Psychiatric rehabilitation technology: Operationalizing the “black box” of the psychiatric rehabilitation process. In: Corrigan Patrick W, Giffort Daniel F., editors. Building teams and programs for effective psychiatric rehabilitation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1998. pp. 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum PS. Psychiatric advance directives and the treatment of committed patients. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55:751–752. 763. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.7.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson JM, Garner HC. Advance directives in mental health. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2003;27:437. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0788-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backlar P, McFarland BH, Swanson JW, Mahler J. Consumer, provider, and informal caregiver opinions on psychiatric advance directives. Administration & Policy in Mental Health. 2001;28:427–441. doi: 10.1023/a:1012214807933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk M, Berk L, Castle D. A collaborative approach to the treatment alliance in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2004;6:504–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair JR, Spreen O. Predicting premorbid IQ: A revision of the National Adult Reading Test. Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1989;3:129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J. The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test: Development of a new memory test with six equivalent forms. Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1991;5:125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen EB, Swanson JW, Appelbaum P, Swartz MS, Ferron J, Van Dorn RA. Competence to complete psychiatric advance directives: Effects of facilitated decision making. Law and Human Behavior. 2007;31:275–289. doi: 10.1007/s10979-006-9064-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen EB, Swartz MS, Van Dorn R, Swanson JW, Kim M, Scheyett A. Clinical decision making and views about psychiatric advance directives. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57:350–355. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.3.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen EB, Tomkins AJ, Pothuloori AP, Scalora MJ. Documentation of violence risk information in psychiatric hospital patient charts: An empirical examination. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry & the Law. 2003;31:58–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisso T, Appelbaum PS, Mulvey EP, Fletcher K. The MacArthur Treatment Competence Study: II. Measures of abilities related to competence to consent to treatment. Law and Human Behavior. 1995;19:127–148. doi: 10.1007/BF01499322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge SK. The Patient Self-Determination Act and psychiatric care. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry & the Law. 1994;22:577–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi KG. Psychiatric advance directives. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2003;9:303–306. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200307000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecomte T, Wallace CJ, Perreault M, Caron J. Consumers’ goals in psychiatric rehabilitation and their concordance with existing services. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:209–211. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman RP. Effective psychiatric rehabilitation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy JP, Apperson L, Appelbaum PS, Ortlip P. Insight in schizophrenia: Its relationship to acute psychopathology. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 1989;177:43–47. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198901000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moerner MG, Mannuzza S, Kane JM. Anchoring the BPRS: An aid to improved reliability. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1988;24:112–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen MI, Ryan C, Rigsby M. Motivational enhancement and MEMS review to improve medication adherence. Behaviour Change. 2002;19:183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist. 2000;55:68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Plant RW, O’Malley S. Initial motivations for alcohol treatment: Relations with patient characteristics, treatment involvement, and dropout. Addictive Behaviors. 1995;20:279–297. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)00072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaulding WD, Sullivan ME, Poland JS. Treatment and rehabilitation of severe mental illness. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Srebnik D. Benefits of psychiatric advance directives: Can we realize their potential? Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice. 2004;4:71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Srebnik D, Appelbaum PS, Russo J. Assessing competence to complete psychiatric advance directives with the competence assessment tool for psychiatric advance directives. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2004;45:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srebnik D, La Fond JQ. Advance directives for mental health treatment. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50:919–925. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.7.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srebnik D, Rutherford LT, Peto T, Russo J, Zick E, Jaffe C, et al. The content and clinical utility of psychiatric advance directives. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:592–598. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.5.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Elbogen EB, Van Dorn RA, Ferron J, Wagner H, et al. Facilitated psychiatric advance directives: A randomized trial of an intervention to foster advance treatment planning among persons with severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1943–1951. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.11.1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Ferron J, Elbogen EB, Van Dorn R. Psychiatric advance directives among public mental health consumers in five U.S. cities: Prevalence, demand, and correlates. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry & Law. 2006;34:43–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Hannon MJ, Elbogen EB, Wagner H, McCauley BJ, et al. Psychiatric advance directives: A survey of persons with schizophrenia, family members, and treatments providers. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health. 2003;2:73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JW, Tepper MC, Backlar P, Swartz MS. Psychiatric advance directives: An alternative to coercive treatment? Psychiatry. 2000;63:160–172. doi: 10.1080/00332747.2000.11024908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Elbogen EB. Psychiatric advance directives: Practical, legal, and ethical issues. Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice. 2004;4:97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dorn R, Swartz MS, Elbogen EB, Swanson JW, Kim M, Ferron J, et al. Clinicians’ attitudes regarding barriers to the implementation of psychiatric advance directives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2006;33:449–460. doi: 10.1007/s10488-005-0017-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuckovich PK. Psychiatric advance directives. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2003;9:55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. WAIS-III administration and scoring manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wilder C, Elbogen EB, Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Van Dorn R. Effect of patients’ reasons for refusing treatment on implementing psychiatric advance directives. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:1348–1350. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.10.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GC, Rodin GC, Ryan RM, Grolnick WS, Deci EL. Autonomous regulation and long-term medication adherence in adult outpatients. Health Psychology. 1998;17:269–276. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygmunt A, Olfson M, Boyer CA, Mechanic D. Interventions to improve medication adherence in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1653–1664. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]