Abstract

A 28-year-old woman presents with a 7-month history of recurrent, crampy pain in the left lower abdominal quadrant, bloating with abdominal distention, and frequent, loose stools. She reports having had similar but milder symptoms since childhood. She spends long times in the bathroom because she is worried about uncontrollable discomfort and fecal soiling if she does not completely empty her bowels before leaving the house. She feels anxious and fatigued and is frustrated that her previous physician did not seem to take her distress seriously. Physical examination is unremarkable except for tenderness over the left lower quadrant. How should her case be evaluated and treated?

THE CLINICAL PROBLEM

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), characterized by chronically recurring abdominal pain or discomfort and altered bowel habits, is one of the most common syndromes seen by gastroenterologists and primary care providers, with a worldwide prevalence of 10 to 15%.1 In the absence of detectable organic causes, IBS is referred to as a functional disorder, which is defined by symptom-based diagnostic criteria known as the “Rome criteria” (Table 1).2

Table 1.

The Rome Diagnostic Criteria for Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS).*

| Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort at least 3 days per month for the past 3 months, associated with two or more of the following: |

| Improvement with defecation |

| Onset associated with a change in frequency of stool |

| Onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool |

Data are from Longstreth et al.2 Criteria must have been fulfilled for the past 3 months, with symptom onset at least 6 months before diagnosis. On the basis of the predominant bowel habit, IBS has been categorized into one of the following subgroups: IBS with diarrhea (more common in men), IBS with constipation (more common in women), and IBS with mixed bowel habits. Each group accounts for about one third of all patients. According to current diagnostic criteria, IBS must be differentiated from functional abdominal pain syndrome (in IBS, symptoms of abdominal pain are associated with alterations in bowel movements) and from chronic functional constipation and chronic functional diarrhea (in IBS, pain and discomfort are associated with altered bowel habits).

IBS is one of several functional gastrointestinal disorders (including functional dyspepsia); these other functional disorders are frequently seen in patients with IBS,3 as are other pain disorders, such as fibromyalgia, chronic pelvic pain, and interstitial cystitis.4,5 Coexisting psychological conditions are also common, primarily anxiety, somatization, and symptom-related fears (e.g., “I am worried that I will have severe discomfort during the day if I don’t empty my bowels completely in the morning”); these contribute to impairments in quality of life6 and excessive use of health care associated with IBS.7

Symptoms characteristic of IBS are common in population-based samples of healthy persons. However, only 25 to 50% of persons with such symptoms (typically those with more frequent or severe abdominal pain) seek medical care.1 Longitudinal studies suggest substantial fluctuations in symptoms over time. In a population-based longitudinal study over a period of 12 years, 55% of subjects who initially reported symptoms of IBS did not report these symptoms at the time of the final survey.3 Although the IBS symptoms resolved in the majority of subjects, transitions to other complexes of gastrointestinal symptoms, such as functional dyspepsia, were also observed.

Symptoms of IBS (or other related functional gastrointestinal symptoms) frequently date back to childhood; the estimated prevalence of IBS in children is similar to that in adults.8 The female-to-male ratio is 2:1 in most population-based samples and is higher among those who seek health care.4 IBS-like symptoms develop in approximately 10% of adult patients after bacterial or viral enteric infections; risk factors for the development of postinfectious IBS include female sex, a longer duration of gastroenteritis, and the presence of psychosocial factors (including a major life stress at the time of infection and somatization).9 Both initial presentations and exacerbations of IBS symptoms are often preceded by major psychological stressors1 or by physical stressors (e.g., gastrointestinal infection).9

Given the direct association between symptoms of IBS and stress, the frequent coexisting psychiatric conditions,10 and the responsiveness of symptoms in many persons to therapies directed at the central nervous system, IBS is often described as a “brain–gut disorder,” although its pathophysiology remains uncertain. Alterations in gastrointestinal motility and in the balance of absorption and secretion in the intestines may underlie irregularities in bowel habits,1 and these abnormalities may be mediated in part by dysregulation of the gut-based serotonin signaling system.11 Increased perception of visceral stimuli may contribute to abdominal pain and discomfort.12 Preliminary reports suggest that alterations in immune activation of the mucosa1,9 and in intestinal microflora13 may contribute to symptoms of IBS, yet a causative role remains to be established.

STRATEGIES AND EVIDENCE

EVALUATION

According to current clinical guidelines,1,2,14,15 IBS can generally be diagnosed without additional testing beyond a careful history taking, a general physical examination, and routine laboratory studies (not including colonoscopy) in patients who have symptoms that meet the Rome criteria (Table 1) and who do not have warning signs. These warning signs include rectal bleeding, anemia, weight loss, fever, family history of colon cancer, onset of the first symptom after 50 years of age, and a major change in symptoms. Patients should be asked about the specifics of their bowel habits and stool characteristics; on the basis of this information, they can be subclassified as having diarrhea-predominant IBS, constipation-predominant IBS, or mixed bowel habits.2

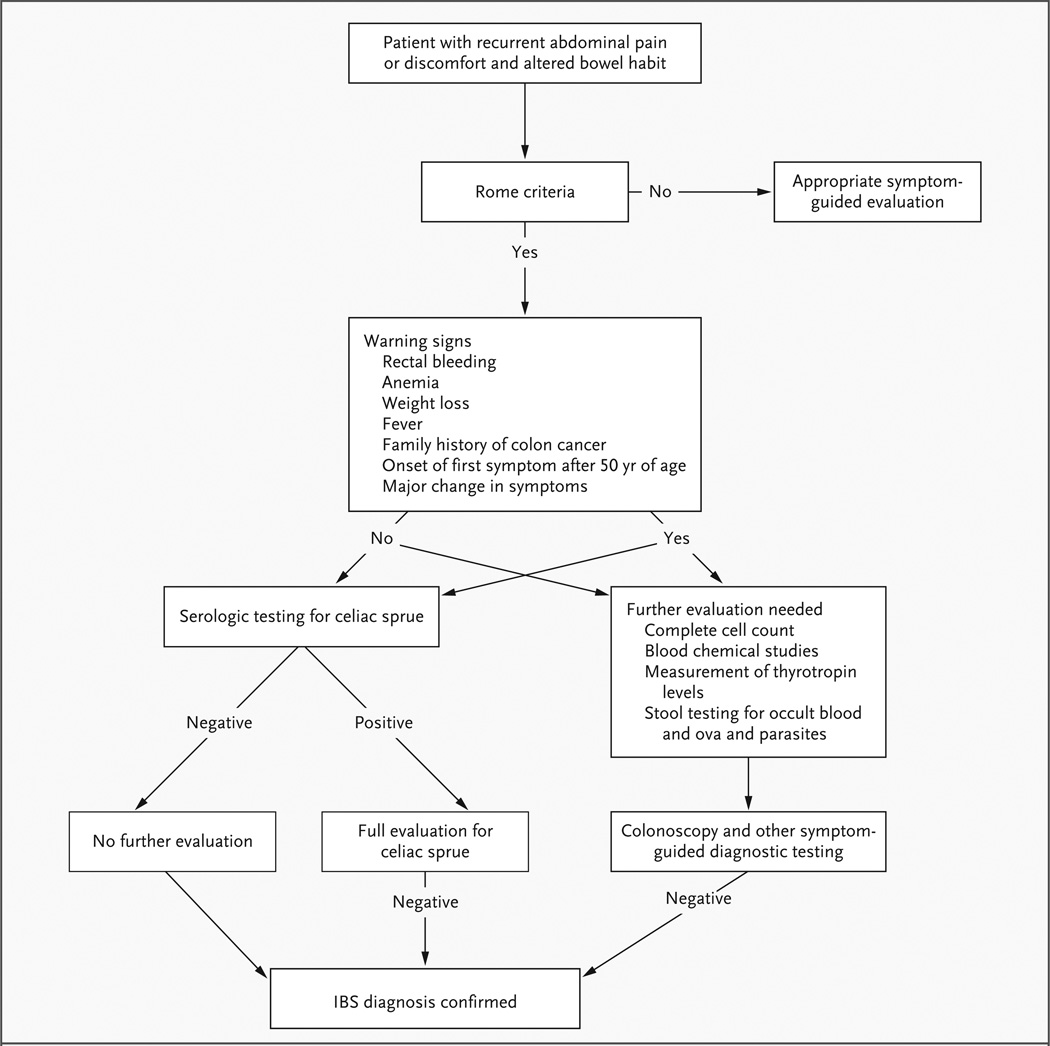

In patients who meet the Rome criteria and have no warning signs, the differential diagnosis includes celiac sprue (Fig. 1), microscopic and collagenous colitis and atypical Crohn’s disease for patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS, and chronic constipation (without pain) for those with constipation-predominant IBS. A relationship between symptoms and food intake, as well as possible triggers for the onset of symptoms (e.g., gastrointestinal infection or marked stressors) should be assessed, since this may guide treatment recommendations. In addition, attention should be paid to symptoms that suggest other functional gastrointestinal and somatic pain disorders and psychological conditions often associated with IBS.

Figure 1. Differential Diagnosis.

Testing for celiac sprue may be useful in patients who meet the Rome criteria16 (especially in those with diarrheapredominant IBS), in patients who have warning signs, and in populations in which the prevalence of celiac sprue is high.17 If there are no warning signs, then basic blood counts, serum biochemical studies, stool testing for occult blood and ova and parasites, and measurement of thyrotropin levels are indicated only if there is a supportive clinical history.18 Colonoscopy is recommended only in patients who have warning signs. However, according to screening guidelines for colon cancer, routine colonoscopy should be performed in patients at the age of 50 years or older, regardless of whether IBS symptoms are present. If there has been a major qualitative change in the pattern of chronic symptoms, a new coexisting condition should be suspected, and a more comprehensive diagnostic approach is warranted.

Clinical experience suggests that accepting the patient’s symptoms and distress as real, and not simply as a manifestation of excessive worrying and somatization, and providing the patient with a plausible model of the disease (e.g., “brain–gut disorder”) facilitates the establishment of a positive patient–doctor relationship. Evidence suggests that an approach that includes acknowledging the disease, educating the patient about the disease, and reassuring the patient may improve the treatment outcome.19 Physical examination frequently reveals tenderness in the left lower quadrant over a palpable sigmoid colon. A rectal examination is warranted to rule out rectal disease and abnormal function of the anorectal sphincter (e.g., paradoxical pelvic-floor contraction during a defecation attempt), which may contribute to symptoms of constipation.

PHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT

Symptomatic treatment (usually aimed at normalizing bowel habits or decreasing abdominal pain) by a reassuring health care provider typically provides relief for patients with mild symptoms who are seen in primary care settings.20 However, the treatment of patients who have more severe symptoms remains challenging. Only a small number of pharmacologic and psychological treatments are supported by well-designed randomized, controlled trials involving patients with IBS. Treatment of IBS with currently available drugs usually is targeted to the management of individual symptoms, such as constipation, diarrhea, and abdominal pain (Table 2).

Table 2.

Medications Used in the Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS).*

| Symptoms and Medication | Initial Dose | Target Dose | Common or Serious Side Effects | Evidence | FDA-Approved | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constipation | mg/day† | For the Symptom | For IBS | For the Symptom | For IBS | ||

| Laxatives‡ and secretory stimulators | |||||||

| Polyethylene glycol 3350 (Miralax, Braintree Labs) | 17,000 | up to 34,000, twice a day | Diarrhea, bloating, cramping | +++ | − | ||

| Lactulose (Kristalose, Cumberland Pharmaceuticals) | 10,000–20,000 | 20,000–40,000 | Diarrhea, bloating, cramping | +++ | − | ||

| Lubiprostone (Amitiza; Takeda, Sucampo) | 24 µg, twice a day | Nausea, diarrhea, headache, abdominal pain and discomfort | +++ | − | Yes§ | No | |

| Prokinetics | |||||||

| Tegaserod (Zelnorm, Novartis) | 6, twice a day | Initial diarrhea, abdominal pain, cardiovascular ischemia (rare) | +++ | +++ | Yes¶ | Yes¶ | |

| Diarrhea | |||||||

| Loperamide (Imodium, McNeil) | 2 | 2–8 | Constipation | +++ | − | Yes | No |

| Alosetron (Lotronex, GlaxoSmithKline)‖ | 0.5, twice a day | up to 1, twice a day | Constipation, ischemic colitis (rare) | − | +++ | No | Yes |

| Bloating | |||||||

| Antibiotics | |||||||

| Rifaximin (Salix) | 400, three times a day | Abdominal pain, diarrhea, bad taste | − | + | No | No | |

| Probiotics** | |||||||

| Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 (Align, Procter & Gamble) | 1 capsule per day | None | + | + | No | No | |

| Pain | |||||||

| Tricyclic antidepressants†† | Dry mouth, dizziness, weight gain | ||||||

| Amitriptyline | 10, at bedtime | 10–75, at bedtime | ++ | + | No | No | |

| Desipramine | 10, at bedtime | 10–75, at bedtime | ++ | + | No | No | |

| Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors‡‡ | Sexual dysfunction, headache, nausea, sedation, insomnia, sweating, withdrawal symptoms | ||||||

| Paroxetine (Paxil CR, GlaxoSmithKline) | 10–60 | − | + | No | No | ||

| Citalopram (Lexapro, Forest) | 5–20 | + | + | No | No | ||

| Fluoxetine (Prozac, Eli Lilly) | 20–40 | Somnolence, dizziness, headaches, insomnia | + | − | No | No | |

This list is not exhaustive but includes major medications for which there is evidence from well-designed clinical trials of effectiveness for global IBS symptoms or for individual symptoms (e.g., constipation, diarrhea, or abdominal pain and discomfort). In the columns about evidence, + denotes some evidence from at least one controlled trial, ++ moderate evidence from several controlled trials or from meta-analysis of such trials, +++ strong evidence from well-designed, controlled clinical trials, and − no evidence. FDA denotes Food and Drug Administration.

Dosages are in milligrams per day unless otherwise noted.

A wide range of osmotic and irritant laxatives, including fiber products, are available over the counter.

Lubiprostone is FDA-approved for the treatment of chronic constipation.

Marketing of tegaserod was suspended by the FDA in March 2007 because of rare cardiovascular side effects but is now available as part of a restricted-access program for women who have constipation-predominant IBS or chronic idiopathic constipation, without known or preexisting heart problems, that is unresponsive to other medications.21

Alosetron use is restricted to women with severe diarrhea-predominant IBS, unresponsive to other medications, owing to side effects.

Many probiotics are available over the counter and are not listed. Align is a probiotic for which a beneficial effect for IBS symptoms has been shown in a high-quality, randomized, controlled trial.

A wide range of tricyclic antidepressants with various side effects and side-effect profiles is available. Two commonly prescribed tricyclic antidepressants are listed. The doses listed are based on clinical experience.

Many selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors are available. Only those that have been evaluated in IBS trials are listed. Also not listed are serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

Constipation

In clinical practice, osmotic laxatives are often useful in the treatment of constipation, although they have not been studied in clinical trials specifically involving patients with IBS. Fiber and other bulking agents have also been used as initial therapy for constipation. However, the frequent side effects (in particular, an increase in bloating) and inconsistent, largely negative results of trials of dietary fiber in the treatment of IBS have decreased the use of this approach.22

Tegaserod, a partial 5-hydroxytryptamine4 (5-HT4)–receptor agonist, has been shown in randomized, clinical trials to be moderately effective for global relief of symptoms in patients with IBS. In an analysis of eight randomized trials, patients assigned to tegaserod were 20% more likely to have global relief of symptoms than those assigned to placebo, with a number needed to treat of 17 to achieve clinically significant global relief. However, marketing of tegaserod was suspended in March 2007, when an analysis of the data from clinical trials identified a significant increase in the number of cardiovascular ischemic events (myocardial infarction, stroke, and unstable angina) in patients taking the drug (13 events in 11,614 patients) as compared with those receiving placebo (1 event in 7031 patients); all events occurred in patients with known cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular risk factors, or both.23 In July 2007, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved an investigationalnew- drug program for tegaserod with access restricted to women younger than 55 years of age who have constipation-predominant IBS (or chronic constipation) without known cardiovascular problems.21

Diarrhea

Although data from randomized trials of traditional antidiarrheal agents in patients with diarrhea- predominant IBS are lacking, clinical experience indicates that these agents are generally effective. Regular use of low doses (e.g., 2 mg of loperamide every morning or twice a day) seems to be effective for the treatment of otherwise uncontrollable diarrhea and may decrease patients’ anxiety about uncontrollable urgency and fecal soiling.

In large, randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled trials involving patients with diarrheapredominant IBS, the 5-HT3–receptor antagonist alosetron at a dose of 1 mg twice a day for 12 weeks decreased stool frequency and bowel urgency, relieved abdominal pain and discomfort, improved scores for global IBS symptoms (i.e., adequate relief of IBS symptoms), and improved health-related quality of life.24 Based on phase 2 trials suggesting that efficacy might be limited to female patients, subsequent trials for FDA approval included only women, and FDA approval was limited to female patients with diarrheapredominant IBS. A later study showed efficacy in men as well, although the indication has not been approved by the FDA.25

In pooled analyses of female patients, alosetron was associated with an odds ratio for adequate relief of pain or global relief of symptoms of 1.8 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.6 to 2.1; number needed to treat for adequate symptom relief, 7.3). However, the FDA has restricted the use of the drug because of rare but serious adverse effects occurring in both clinical trials and post-marketing studies, including complications from constipation (ileus, bowel obstruction, fecal impaction, and perforation; combined prevalence, 0.10% in the alosetron group vs. 0.06% in the placebo group [from clinical trials dating up to 2000])26 and ischemic colitis (prevalence, 0.15% in the alosetron group vs. 0.06% in the placebo group). Thus, alosetron is indicated only for women with severe diarrhea-predominant IBS who have had symptoms for at least 6 months and who have not had a response to conventional therapies (in particular, antidiarrheal agents).

Abdominal Pain

Antispasmodic agents (e.g., hyoscyamine or mebeverine) have been used for the treatment of pain in patients with IBS. However, data from highquality randomized, controlled trials of their effectiveness in reducing pain or global symptoms are lacking.22

Tricyclic antidepressant medications are commonly used for IBS symptoms, often in low doses (e.g., 10 to 75 mg of amitriptyline). Hypothesized mediators of their effects include antihyperalgesia, improvement in sleep, normalization of gastrointestinal transit,27 and when used at higher doses (e.g., 100 mg or more at bedtime), treatment of coexisting depression and anxiety. Despite their frequent use in practice, data on the efficacy of tricyclic antidepressants in patients with IBS are inconsistent. Two meta-analyses (including 11 randomized, controlled trials) showed that low-to-moderate doses of tricyclic antidepressants significantly reduced pain and overall symptoms in patients with IBS,1,28,29 but the analyses have been criticized for the inclusion of studies that enrolled subjects with functional dyspepsia. A third meta-analysis that excluded these studies showed that tricyclic antidepressants were not superior to placebo.15

In the largest published randomized, placebo-controlled trial to date, treatment with desipramine (with an escalating dose from 50 to 150 mg) was not superior to placebo in intention-to-treat analyses. However, a secondary analysis (per protocol) limited to patients with detectable plasma levels of desipramine showed a significant benefit over placebo.30 These patients presumably adhered better to the protocol. Also, given the high dose of desipramine that was studied, it is unclear whether reported improvement in IBS symptoms was secondary to treatment of coexisting depression or anxiety. Effects of tricyclic antidepressants on sensitivity to somatic pain31 and sleep suggest that they may have particular benefit in patients with IBS who have widespread somatic pain or who sleep poorly, although this has not been studied explicitly.

Several small, randomized, controlled trials suggest that selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors may have beneficial effects in patients with IBS, most commonly on measures of general well-being and, in some studies, on abdominal pain.32 However, it remains unclear whether a lessening of depression or anxiety explains the benefits. Although serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (duloxetine and venlafaxine) have been shown to be effective in reducing pain in other chronic pain conditions, including fibromyalgia,11 data from randomized, controlled trials of their role in the treatment of IBS are lacking.

There is a high prevalence of coexisting anxiety in patients with IBS. Nevertheless, benzodiazepines are not recommended for long-term therapy because of the risk of habituation and the potential for dependency.8

COGNITIVE–BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

Cognitive–behavioral therapy (a combination of cognitive and behavioral techniques) is the beststudied psychological treatment for IBS.15,33 Cognitive techniques (typically administered in a group or an individual format in 4 to 15 sessions) are aimed at changing catastrophic or maladaptive thinking patterns underlying the perception of somatic symptoms.1,34 Behavioral techniques aim to modify dysfunctional behaviors through relaxation techniques, contingency management (rewarding healthy behaviors), or assertion training. Some randomized, controlled trials have also shown reductions in IBS symptoms with the use of gut-directed hypnosis (aimed at improving gut function), which involves relaxation, change in beliefs, and self-management.33,35

Data from head-to-head comparisons of psychotherapy with pharmacotherapy for IBS or psychotherapy plus pharmacotherapy with pharmacotherapy alone are lacking. The magnitude of improvement that has been reported with psychological treatments seems to be similar to or greater than that reported with medications studied specifically for bowel symptoms in IBS, although comparisons are limited by, among other things, the lack of a true placebo control in trials of psychotherapies. In a meta-analysis of 17 randomized trials of cognitive treatments, behavioral treatments, or both for IBS (including hypnosis), as compared with control treatments (including waiting list, symptom monitoring, and usual medical treatment), those patients who were randomly assigned to cognitive–behavioral therapy were significantly more likely to have a reduction in gastrointestinal symptoms of at least 50% (odds ratio, 12; 95% CI, 6 to 260),33 and the estimated number needed to treat with cognitive–behavioral therapy or hypnotherapy for one patient to have improvement was estimated to be two.33

AREAS OF UNCERTAINTY

The optimal means of treating patients with moderate or severe symptoms remains uncertain, particularly given the implementation of restricted-access programs for the newer pharmacotherapies for diarrhea-predominant IBS and constipation-predominant IBS.

Limited data from small, randomized, controlled trials have suggested benefits of nonabsorbable antibiotics36 (400 mg of rifaximin three times a day), and probiotics,37,38 particularly for symptoms of gas and bloating. More data are needed from larger, high-quality randomized, controlled trials that assess the effects of these and other therapies, including antidepressant agents, and provide information on factors that may predict responsiveness to these therapies. Lubiprostone (24 µg twice a day) has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of chronic constipation and was recently shown to be effective in the treatment of constipation-predominant IBS.39 The roles of this agent and other new treatments for constipation and global relief of symptoms (e.g., linaclotide40) in constipation-predominant IBS remain to be established.

GUIDELINES

Guidelines for the management of IBS have been issued by the American Gastroenterological Association,1 by the American College of Gastroenterology,15 by the Rome Foundation,2 and by the British Society of Gastroenterology.14 Because of the limited data from randomized trials involving patients with IBS, these guidelines are based largely on consensus opinion. My recommendations are generally consistent with these guidelines.

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In patients such as the woman in the vignette, who present with symptoms suggestive of IBS, including chronic abdominal pain and discomfort associated with diarrhea, the first step in evaluation is a careful history taking to rule out warning signs, including unexplained weight loss and hematochezia. In the absence of any warning signs, the diagnosis usually can be made clinically without the need for further testing (Fig. 1). I would also determine whether a gastrointestinal infection or any major life event preceded the recent flare of symptoms, since these are common triggers of IBS.

Clinical experience suggests that mild symptoms may be managed effectively by symptomatic treatment of altered bowel habits (e.g., antidiarrheal agents or laxatives). I find it helpful to make it clear to the patient that I accept his or her symptoms as real and to provide a pathophysiological explanation of symptoms.

For severe diarrhea, as in the case described, I typically recommend starting a low daily dose of loperamide (2 to 4 mg every morning, noting that this can be increased if the patient has a particularly important activity), with the expectation that this treatment may also decrease anxiety about having uncontrollable bowel movements during the day. Although the data from randomized trials are conflicting with regard to the role of tricyclic antidepressant agents in patients with IBS, I would also consider this therapy (e.g., amitriptyline, starting at a dose of 10 mg at bedtime and gradually, over a period of several weeks, increasing to the maximum tolerated dose, but not higher than 75 mg at bedtime), making it clear to the patient that low-dose therapy is not aimed at altering mood but rather is aimed at reducing IBS symptoms, including abdominal pain. I would recommend participation in a cognitive– behavioral therapy program (ideally in the form of a brief, self-administered program),34 although there are no data showing that the combination of cognitive–behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy is superior to either treatment alone in cases of IBS. If symptoms failed to improve sufficiently in this patient with diarrhea, I would discuss with her the potential addition of alosetron, but with attention to its potential for rare serious adverse effects, including ischemic colitis.14

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants (P50 DK64539, R24 AT002681, R01 DK48351, and R01 DK58173) from the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Mayer reports receiving research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Avera and consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Johnson & Johnson, Prometheus, Dannon, and Nestlé.

I thank Teresa Olivas and Cathy Liu for invaluable assistance in preparing the manuscript, and Lin Chang, Douglas Drossman, Jeff Lackner, and Brennan Spiegel for valuable comments.

Footnotes

No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2108–2131. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, et al., editors. Rome III: the functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, VA: Degnon; 2006. pp. 487–555. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halder SL, Locke GR, III, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ, III, Talley NJ. Natural history of functional gastrointestinal disorders: a 12-year longitudinal population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:799–807. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR. Systemic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1140–1156. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wessely S, White PD. There is only one functional somatic syndrome. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:95–96. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spiegel BM, Gralnek IM, Bolus R, et al. Clinical determinants of health-related quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1773–1780. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.16.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy RL, Von Korff M, Whitehead WE, et al. Costs of care for irritable bowel syndrome patients in a health maintenance organization. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3122–3129. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Lorenzo C, Rasquin A, Forbes D, et al. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, et al., editors. Rome III: the functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, VA: Degnon; 2006. pp. 723–777. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spiller R, Campbell E. Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006;22:13–17. doi: 10.1097/01.mog.0000194792.36466.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayer EA, Craske MG, Naliboff BD. Depression, anxiety, and the gastrointestinal system. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl:8):28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gershon MD, Tack J. The serotonin signaling system: from basic understanding to drug development for functional GI disorders. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:397–414. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayer EA, Gebhart GF. Basic and clinical aspects of visceral hyperalgesia. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:271–293. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kassinen A, Krogius-Kurikka L, Mäkivuokko H, et al. The fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients differs significantly from that of healthy subjects. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:24–33. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spiller R, Aziz Q, Creed F, et al. Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management. Gut. 2007;56:1770–1798. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.119446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandt LJ, Bjorkman D, Fennerty MB, et al. Systematic review on the management of irritable bowel syndrome in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(Suppl):S7–S26. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9270(02)05657-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cash BD, Schoenfeld P, Chey WD. The utility of diagnostic tests in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2812–2819. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spiegel BM, DeRosa VP, Gralnek IM, Wang V, Dulai GS. Testing for celiac sprue in irritable bowel syndrome with predominant diarrhea: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1721–1732. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamm LR, Sorrells SC, Harding JP, et al. Additional investigations fail to alter the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome in subjects fulfilling the Rome criteria. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1279–1282. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spiegel BM, Naliboff B, Mayer E, Bolus R, Gralnek I, Shekelle P. The effectiveness of a model physician-patient relationship versus usual care in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(Suppl 2):A-112. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ilnyckyj A, Graff LA, Blanchard JF, Bernstein CN. Therapeutic value of a gastroenterology consultation in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:871–880. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rockville, MD: News release of the Food and Drug Administration; 2007. Jul 27, [Accessed March 24, 2008]. FDA permits restricted use of Zelnorm for qualifying patients. at http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2007/NEW01673.html. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tack J, Fried M, Houghton LA, Spicak J, Fisher G. Systematic review: the efficacy of treatments for irritable bowel syndrome — a European perspective. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:183–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pasricha PJ. Desperately seeking serotonin.… A commentary on the withdrawal of tegaserod and the state of drug development for functional and motility disorders. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2287–2290. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradesi S, Tillisch K, Mayer E. Emerging drugs for irritable bowel syndrome. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2006;11:293–313. doi: 10.1517/14728214.11.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang L, Ameen VZ, Dukes GE, Mc-Sorley DJ, Carter EG, Mayer EA. A dose-ranging, phase II study of the efficacy and safety of alosetron in men with diarrhea-predominant IBS. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:115–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang L, Chey WD, Harris L, Olden K, Surawicz C, Schoenfeld P. Incidence of ischemic colitis and serious complications of constipation among patients using alosteron: systematic review of clinical trials and post-marketing surveillance data. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1069–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. Use of psychopharmacological agents for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut. 2005;54:1332–1341. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.048884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson JL, O’Malley PG, Tomkins G, Balden E, Santoro J, Kroenke K. Treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders with antidepressant medications: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2000;108:65–72. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00299-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lesbros-Pantoflickova D, Michetti P, Fried M, Beglinger C, Blum AL. Meta-analysis: the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1253–1269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drossman DA, Toner BB, Whitehead WE, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy versus education and desipramine versus placebo for moderate to severe functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:19–31. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00669-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005454. CD005454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mayer EA, Tillisch K, Bradesi S. Modulation of the brain-gut axis as a therapeutic approach in gastrointestinal disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:919–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lackner JM, Mesmer C, Morley S, Dowzer C, Hamilton S. Psychological treatments for irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:1100–1113. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Krasner SS, Katz LA, Gudleski GD, Holroyd K. Self administered cognitive behavior therapy for moderate to severe IBS: clinical efficacy, tolerability, feasibility. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.03.004. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whorwell PJ. The history of hypnotherapy and its role in the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:1061–1067. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pimentel M, Park S, Mirocha J, Kane SV, Kong Y. The effect of a nonabsorbed oral antibiotic (rifaximin) on the symptoms of the irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:557–563. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-8-200610170-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Mahony L, McCarthy J, Kelly P, et al. Lactobacillus and bifidobacterium in irritable bowel syndrome: symptom responses and relationship to cytokine profiles. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:541–551. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quigley EM, Flourie B. Probiotics and irritable bowel syndrome: a rationale for their use and an assessment of the evidence to date. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19:166–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johanson JF, Drossman DA, Panas R, Wahle A, Ueno R. Clinical trial: phase 2 trial of lubiprostone for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03629.x. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andresen V, Camilleri M, Busciglio IA, et al. Effect of 5 days linaclotide on transit and bowel function in females with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:761–768. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]