Abstract

Purpose

Since prior studies have suggested that male physicians earn more than their female counterparts, the authors examined whether this disparity exists in a recently hired cohort.

Method

In 2010-11, the authors surveyed recent recipients of National Institutes of Health (NIH) mentored career development (i.e., K08 or K23) awards, receiving responses from 1,275 (75% response rate). For the 1,012 physicians with academic positions in clinical specialties who reported salary, they constructed linear regression models of salary considering gender, age, race, marital status, parental status, additional doctoral degree, academic rank, years on faculty, specialty, institution type, region, institution NIH funding rank, K-award type, K-award funding institute, K-award year, work hours, and research time. They evaluated the explanatory value of spousal employment status using Peters-Belson regression.

Results

Mean salary was $141,325 (95% confidence interval [CI] 135,607-147,043) for women and $172,164 (95% CI 167,357-176,971) for men. Male gender remained an independent, significant predictor of salary (+$10,921, P < 0.001) even after adjusting for specialty, academic rank, work hours, research time, and other factors. Peters-Belson analysis indicated that 17% of the overall disparity in the full sample was unexplained by the measured covariates. In the married subset, after accounting for spousal employment status, 10% remained unexplained.

Conclusions

The authors observed, in this recent cohort of elite, early-career physician researchers, a gender difference in salary that was not fully explained by specialty, academic rank, work hours, or even spousal employment. Creating more equitable procedures for establishing salary at academic institutions is important.

Previous studies have suggested that male physicians earn higher salaries than their female counterparts, but the mechanisms underlying much of this difference remain poorly understood.1-9 Differences in the distribution of men and women into different specialties, work hours, and productivity have explained some of the observed difference; however, prior studies have indicated that a substantial proportion of the difference remains unexplained even after those variables are taken into account.1

In prior work, our group documented an unexplained gender difference in salary even within a relatively homogeneous population of mid-career physician researchers.1 Given the extensive list of potential factors for which we controlled, including specialty, work hours, and productivity, we speculated that the difference observed might be rooted in gender-related differences in values or behaviors. For example, men might prioritize compensation more highly, either due to prevailing societal expectations of gender roles or the greater likelihood of a man serving as the sole breadwinner in a family. Similarly, men might negotiate more aggressively for salary. Employer attitudes may also play a role. Employers might value men's contributions more than women's. Alternatively, employers might view men as needing higher salaries (due to the notion of a “family wage”)10 if men are less likely to be in two-income households. However, like others, our prior work was limited by lack of information on the employment of the respondent's spouse, precluding the ability to ascertain whether some of the gender effect on salary may have been mediated by spousal employment. Moreover, the sample of physician researchers we previously considered had commenced their academic careers over a decade ago, and recent efforts to decrease inequities may have been successful with younger cohorts.

Therefore, we sought to evaluate gender differences in salary in a new population of physician-researchers who were similarly select and homogeneous, but who were early in their careers: physicians who received K08 and K23 awards (i.e., prestigious National Institutes of Health [NIH] mentored career development grants) between 2006 and 2009. We sought to evaluate whether the gender differences we previously observed in a mid-career population of elite physician-researchers would be apparent in this younger and more recently hired cohort at this earlier point in their career trajectories. In addition, we included questions eliciting spousal employment status (fulltime, part-time, or not employed) and the perceived level of dependence of the family unit upon the respondent for financial support in order to determine how much of any observed gender difference in salary might be mediated by spousal employment and gender roles within the family.

Method

Data collection

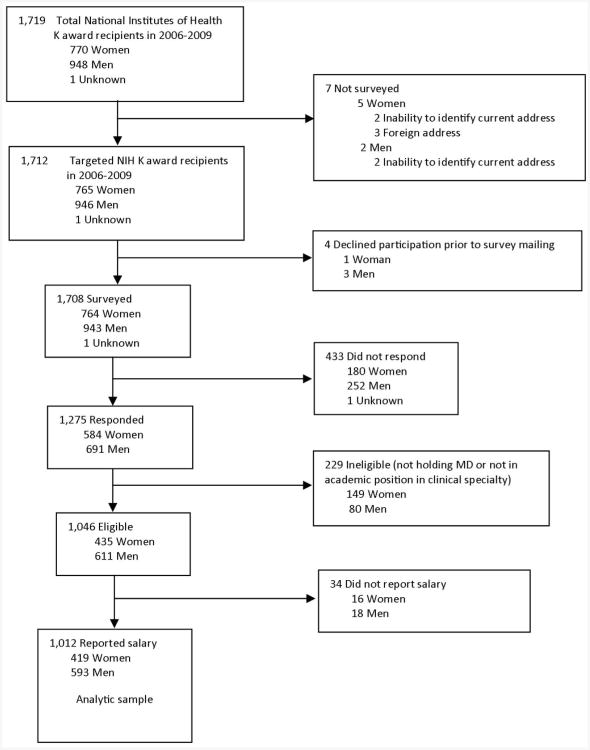

In 2010, using the NIH RePORTER database,11 we identified 1,719 researchers who received new K08 and K23 awards in 2006 through 2009. After receiving approval from the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (IRB), we conducted Internet searches and made telephone calls to obtain the current U.S. mailing addresses of these K award recipients. We obtained 1,708 valid U.S. mailing addresses (see also Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The evolution, by gender, of the analytic sample from the original pool of all 1,719 individuals who received new National Institutes of Health mentored research (i.e., K08 or K23) awards in 2006-2009.

Between August 2010 and February 2011, we sent a survey questionnaire and a $50 incentive to all 1,708 of these K award recipients. We enclosed a cover letter that explained that this was an IRB-approved research study investigating the experiences of individuals who received K08 and K23 awards from the NIH. The cover letter stated the voluntary nature of participation, our efforts to ensure confidentiality, the minimal risks involved (e.g., possible loss of confidentiality), and our source of funding for the study. It also included contact information for the IRB and the principal investigator. Following a modified Dillman approach (which employed an initial contact letter, a tailored questionnaire, and subsequent correspondence),12 we also sent a follow-up questionnaire to non-respondents. Upon receipt of the completed questionnaires, we merged survey responses to data previously collected from RePORTER on K award type, year, and institution characteristics.

Measures

We designed the questionnaire after reviewing the relevant literature,1- 9,12 considering instruments used in other research to determine outcomes of academic careers,3,13 and conducting detailed cognitive pretesting.14 Ultimately, the questionnaire comprised 173 items that assessed demographics, education, time allocation, academic experiences, family responsibilities, and salary.

The principal dependent variable for the analysis was current annual salary, which we structured as a continuous variable rounded to the nearest thousand dollars. We also analyzed several independent variables as continuous variables: age, number of years on faculty, number of hours spent working (work hours), and percentage of time spent conducting research (research time).

As described in greater detail in previous studies,1,15 we grouped specialties into four categories based upon their nature: (1) internal medicine and its subspecialties, (2) surgical specialties, (3) specialties related to the care of children, women, and families (family practice, obstetrics/gynecology, and pediatrics and its subspecialties), and (4) hospital-based specialties (emergency medicine, anesthesiology, pathology, and radiology). We also grouped specific specialties into four pay-level categories (low, medium, high, and extremely high) based upon Association of American Medical Colleges data on median salary in that specialty in 2009, as described elsewhere.1 This additional grouping allowed for finer distinctions between subspecialties that are similar in nature but have different earning potential.

We grouped institutions such that all hospitals affiliated with a single university were considered to be a single institution. We then grouped the institutions employing the researchers into four tiers containing roughly equal numbers of K-awardees, based on the amount of total NIH funding received (i.e., first tier = the institutions receiving the most NIH funding and fourth tier = the institutions receiving the least NIH funding), as well as into categories for public or private.1,15 We grouped institution location into 4 categories based upon region of country (Northeast, South, Midwest, and West).

We grouped the NIH-institutes that funded respondents' K-awards (e.g., National Cancer Institute, National Institute for Mental Health) into three tiers of funding activity, based upon the total dollar amount of R01 awards granted in 2000 (i.e., first tier = those granting the highest dollar amount of R01 grants, second tier = those in the middle, and third tier = those granting the least).1,15

We divided faculty as follows: by academic rank into 5 groups, by year of K award into 4 groups, by race (as self-reported in multiple-choice questions) into 4 groups, and by marital status into 3 groups (married or in domestic partnership, single, or divorced/widowed). We grouped spousal employment status into 3 categories (full-time, part-time, and not working). K-award type, parental status, and possession of an additional PhD degree were binary variables, as was gender.

We also asked respondents how much their compensation depends upon clinical volume or number of patients seen, as well as how much their compensation depends upon amount of grant funding received. Another item asked respondents, “How dependent is your family upon your income to maintain an acceptable lifestyle?” We scored all of these items on a four-point response scale ranging from “not at all” to “very much.”

Data analysis

We performed statistical analyses using the SAS System, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). We compared respondents to nonrespondents by those characteristics for which public data were available so as to evaluate for potential bias related to non-response. After comparing those who reported their salary to those who did not, we limited our sample to individuals holding MD degrees with academic positions in clinical specialties who reported their salary.

We described characteristics of this sample by gender and then constructed multiple variable linear regression models for salary. We began with the following respondent characteristics: gender, age, race, marital status, parental status, additional PhD degree, academic rank, number of years on faculty, specialty, specialty pay level, current institution type (public or private), current institution region, current institution NIH funding tier, K-award type, K-award funding institute tier, K-award year, work hours, and research time. Most characteristics were categorical and modeled as indicator variables with a reference category. We centered continuous characteristics (e.g., age, work hours) at their means. We constructed both a full model using all covariates and a parsimonious model whereby we iteratively deleted variables from the model based upon improvement in Akaike's Information Criterion,16 using both forward stepwise and backward elimination approaches. We also explored pairwise interactions between gender and the other characteristics. These multivariable models offer estimates of the association between gender and salary, independent of the other variables included.

To explore the explanatory value of spousal employment within the married or partnered subset of our sample, we used the Peters-Belson approach. This approach allows for the decomposition of an observed gender difference in salary into two components: the component that is explained by gender differences in other measured characteristics and the component that remains unexplained. Specifically, we developed a regression model using all measured characteristics for the men alone. We then applied the coefficients from that model to the characteristics for each woman to derive her expected salary, as if her gender were male, in order to quantify the proportion of the observed gender difference unexplained by the measured characteristics.17-21 We first conducted this exercise in the married/partnered subset without including spousal employment status and then repeated it after including spousal employment status, to measure the explanatory impact of that variable.

For statistical inference, we conducted two-tailed tests with test statistics, considering P values at or below 5% to be significant.

Results

We received 1,275 completed questionnaires from the 1,708 individuals we contacted for a response rate of 75% (see Figure 1). Our respondent sample did not differ significantly from non-respondents by gender or K-award year. A higher proportion of K23 recipients (645/831, 78%) responded than did K08 recipients (630/888, 71%, P = 0.002). Individuals at institutions with lower overall NIH funding were more likely to respond (322/401[80%] from the lowest/fourth tier; 349/474 [74%] from the third tier; 353/486 [73%] from the second tier; and 236/340 [69%] from the top/first tier, P = 0.006). Of the 1,275 respondents, 1,055 (83%) held MD degrees—and of these 1,046 (99%) held academic positions in clinical specialties. Finally, of these 1,046, we used the 1,012 (97%) who reported salary information to constitute the analytic sample.

The characteristics of the 419 female and 593 male K award recipients in the analyzed sample are detailed in Table 1. Women were more likely to be single (8.6% vs 4.2%, P = 0.01). Of those who were married/partnered, men were far more likely to have a spouse who was not employed (26.5% vs 7.5%, P < 0.001) or employed part-time (28.0% vs 6.4%, P < 0.001). Women were nearly twice as likely to be in the lowest paying specialties (45.1% vs 24.1%, P < 0.001), more likely to hold K23 (rather than K08) awards (58.2% vs 35.4%, P < 0.001), and more likely to be funded by NIH institutes that awarded lower amounts of independent funding (38.0% vs 25.3%, P < 0.001). Women's mean work hours were lower than men's (54.0 vs 59.4, P < 0.001).

Table 1. Characteristics of a Sample (n = 1,012) of Early Career Physician-Researchers Holding Academic Positions in Clinical Specialties Who Received National Institutes of Health (NIH) Mentored Career Awards from 2006 -- 2009.

| Characteristic | No. (%* of 419) women | No. (%* of 593) men | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reported race | 0.60 | ||

| White | 280 (66.8) | 408 (68.8) | |

| Black | 14 (3.3) | 12 (2.0) | |

| Asian | 105 (25.1) | 145 (24.5) | |

| Other | 17 (4.1) | 25 (4.2) | |

| Not reported | 3 (0.7) | 3 (0.5) | |

| Marital status | 0.01 | ||

| Married or domestic partnership | 373 (89.0) | 551 (92.9) | |

| Single (never married) | 36 (8.6) | 25 (4.2) | |

| Divorced or widowed | 9 (2.2) | 17 (2.9) | |

| Not reported | 1 (0.2%) | 0 | |

| Parental status | 0.16 | ||

| Yes | 333 (79.5) | 492 (83.0) | |

| No | 86 (20.5) | 101 (17.0) | |

| Employment status of spouse/domestic partner† | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes, full time | 320 (85.8) | 247 (44.8) | |

| Yes, part time | 24 (6.4) | 154 (28.0) | |

| No | 28 (7.5) | 146 (26.5) | |

| Not reported | 1 (0.3) | 4 (0.7) | |

| Additional PhD degree/s | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 88 (21.0) | 204 (34.4) | |

| No | 331 (79.0) | 389 (65.6) | |

| Academic rank | 0.07 | ||

| Fellow/research scientist | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.7) | |

| Instructor | 44 (10.5) | 48 (8.1) | |

| Assistant professor | 318 (75.9) | 426 (71.8) | |

| Associate professor | 54 (12.9) | 111 (18.7) | |

| Professor | 2 (0.5) | 4 (0.7) | |

| Specialty | < 0.001 | ||

| Medical specialties | 231 (55.1) | 318 (53.6) | |

| Clinical specialties for women, children, and families | 129 (30.8) | 120 (20.2) | |

| Hospital-based specialties (e.g., emergency, anesthesiology, pathology, and radiology) | 49 (11.7) | 98 (16.5) | |

| Surgical specialties | 10 (2.4) | 57 (9.6) | |

| Specialty pay level‡ | < 0.001 | ||

| Low-paying | 189 (45.1) | 143 (24.1) | |

| Moderately-paying | 175 (41.7) | 283 (47.7) | |

| High-paying | 44 (10.5) | 96 (16.2) | |

| Extremely high-paying | 11 (2.6) | 71 (12.0) | |

| K award institution type | 0.36 | ||

| Private | 234 (55.8) | 313 (52.8) | |

| Public | 180 (43.0) | 271 (45.7) | |

| Not reported | 5 (1.2%) | 9 (1.5%) | |

| K award institution NIH funding tier§ | 0.91 | ||

| First | 85 (20.3) | 119 (20.1) | |

| Second | 119 (28.4) | 179 (30.2) | |

| Third | 122 (29.2) | 162 (27.3) | |

| Fourth | 89 (21.2) | 125 (21.1) | |

| Not reported | 4 (1.0%) | 8 (1.3%) | |

| K award institution region | 0.57 | ||

| Northeast | 174 (41.5) | 224 (37.8) | |

| South | 47 (11.2) | 77 (13.0) | |

| Midwest | 102 (24.3) | 143 (24.1) | |

| West | 96 (22.9) | 149 (25.1) | |

| K award type | < 0.001 | ||

| K08 | 175 (41.8) | 383 (64.6) | |

| K23 | 244 (58.2) | 210 (35.4) | |

| K award year | 0.15 | ||

| 2006 | 93 (22.2) | 144 (24.3) | |

| 2007 | 109 (26.0) | 122 (20.6) | |

| 2008 | 96 (22.9) | 160 (27.0) | |

| 2009 | 121 (28.9) | 167 (28.2) | |

| Funding institute tier¶ | < 0.001 | ||

| First | 88 (21.0) | 198 (33.4) | |

| Second | 172 (41.0) | 245 (41.3) | |

| Third | 159 (38.0) | 150 (25.3) | |

| Characteristic | No. (SD) | No. (SD) | P value |

| Mean age in years | 39.9 (3.7) | 40.5 (3.7) | 0.01 |

| Mean number of years on faculty | 4.7 (2.5) | 4.6 (2.5) | 0.85 |

| Mean number of hours spent working | 54.0 (9.7) | 59.4 (10.6) | < 0.001 |

| Mean percentage of time spent conducting research | 65.4 (16.8) | 65.7 (17.1) | 0.73 |

Percentages may not equal 100 due to rounding.

Applies only to the married/partnered sample (n = 924).

Based on salaries as reported in the Association of American Medical Colleges Faculty Salary Survey Reports, which are available through www.aamc.org/publications. Examples of specialties within each category are as follows: extremely high paying = neurosurgery and radiology; high paying = emergency medicine and gastroenterology; moderately paying = neurology and pathology; low paying = pediatrics and family medicine.

Institutions ranked and then grouped into four groups with roughly equal numbers of K awardees, based on total amount of NIH funding received, as previously defined in detail in Jagsi R, Motomura AR, Griffith KA, Rangarajan S, Ubel PA. Sex differences in attainment of independent funding by career development awardees. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:804-811.

NIH funding institutes (e.g., National Cancer Institute, National Institute for Mental Health) ranked based on the dollar amount of R01 grants awarded and then grouped into those awarding the highest amount of funding (first), those in the middle (second), and those awarding the least (third), as previously defined in detail in Jagsi R, Motomura AR, Griffith KA, Rangarajan S, Ubel PA. Sex differences in attainment of independent funding by career development awardees. Ann Intern Med. 20091;151:804-811.

Overall, mean salary was $141,325 (95% confidence interval [CI] $135,607 – $147,043) for women and $172,164 (95% CI $167,357 – $176,971) for men in this sample. Table 2 presents the results of our bivariate analysis on the correlates of salary (i.e., the personal, family, professional, K-award, and institutional demographics described in Method).

Table 2. Associations Between Self-Reported Annual Salary and Various Characteristics of Early Career Physician-Researchers (n = 1,012) Holding Academic Positions in Clinical Specialties Who Received National Institutes of Health (NIH) Mentored Career Awards from 2006 – 2009: Bivariable Analyses.

| Characteristic | Salary estimate in U.S. $ | 95% confidence interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | < 0.001 | ||

| Women | 141,325 | 135,607 – 147,043 | |

| Men | 172,164 | 167,357 – 176,971 | |

| 1-year increase in age | 2,099 | 1,084 – 3,113 | < 0.001 |

| Self-reported race | 0.64 | ||

| White | 158,499 | 153,689 – 162,912 | |

| Black | 150,885 | 127,128 – 174,641 | |

| Asian | 163,405 | 155,747 – 171,063 | |

| Other | 159,310 | 140,627 – 177,992 | |

| Marital status | 0.04 | ||

| Married | 160,025 | 156,060 – 163,989 | |

| Divorced/widowed | 176,885 | 153,253 – 200,516 | |

| Single/never married | 143,061 | 127,633 – 158,489 | |

| Parental Status | |||

| Yes | 162,151 | 157,962 – 166,341 | 0.002 |

| No | 146,923 | 138,076 – 155,770 | |

| Additional PhD degree/s | 0.16 | ||

| Yes | 155,142 | 148,080 – 162,203 | |

| No | 161,121 | 156,624 – 165,618 | |

| Academic rank | < 0.001 | ||

| Fellow/research scientist | 107,000 | 56,774 – 157,226 | |

| Instructor | 117,022 | 105,313 – 128,731 | |

| Assistant professor | 154,877 | 150,759 – 158,994 | |

| Associate professor | 202,539 | 193,796 – 211,283 | |

| Full professor | 226,667 | 180,817 – 272,516 | |

| 1-year increase in number of years on faculty | 5,820 | 4,346 – 7,294 | < 0.001 |

| Specialty | < 0.001 | ||

| Medical specialties | 147,396 | 140,176 – 153,007 | |

| Clinical specialties for women, children, and families | 146,591 | 140,176 – 153,007 | |

| Hospital-based specialties (e.g., emergency, anesthesiology, pathology, and radiology) | 170,010 | 161,660 – 178,360 | |

| Surgical specialties | 282,015 | 269,646 – 293,383 | |

| Specialty pay level* | < 0.001 | ||

| Low-paying | 127,287 | 122,668 – 131,906 | |

| Moderately-paying | 150,341 | 146,408 – 154,273 | |

| High-paying | 186,136 | 179,023 – 193,249 | |

| Extremely high-paying | 294,317 | 285,023 – 303,611 | |

| K award institution type | 0.28 | ||

| Public | 157,171 | 151,998 – 162,344 | |

| Private | 161,410 | 155,713 – 167,107 | |

| K award institution NIH funding tier† | < 0.001 | ||

| First | 143,743 | 135,404 – 152,081 | |

| Second | 156,314 | 149,415 – 163,213 | |

| Third | 158,632 | 151,565 – 165,699 | |

| Fourth | 178,910 | 170,768 – 187,051 | |

| K award institution region | 0.10 | ||

| West | 154,686 | 147,004 – 162,367 | |

| Midwest | 170,343 | 162,662 – 178,024 | |

| South | 161,249 | 150,452 – 172,046 | |

| Northeast | 154,686 | 147,004 – 162,367 | |

| K award type | 0.008 | ||

| K08 | 164,017 | 158,921 – 169,112 | |

| K23 | 153,716 | 148,067 – 159,365 | |

| Years since receipt of K award | 0.004 | ||

| 4 | 171,393 | 163,591 – 179,196 | |

| 3 | 156,796 | 148,893 – 164,669 | |

| 2 | 158,595 | 151,087 – 166,102 | |

| 1 | 152,319 | 145,242 – 159,397 | |

| Funding institute tier‡ | < 0.001 | ||

| First | 175,622 | 168,608 – 182,637 | |

| Second | 147,072 | 141,263 – 152,881 | |

| Third | 161,008 | 154,259 – 167,756 | |

| 1-hour increase in number of hours spent working | 1,634 | 1,288 – 1,980 | < 0.001 |

| 1-percentage point increase in percentage of time spent conducting research | -1,062 | -1,276 – -847 | < 0.001 |

Based on salaries as reported in the Association of American Medical Colleges Faculty Salary Survey Reports, which are available through www.aamc.org/publications. Examples of specialties within each category are as follows: extremely high paying = neurosurgery and radiology; high paying = emergency medicine and gastroenterology; moderately paying = neurology and pathology; low paying = pediatrics and family medicine.

Institutions ranked and then grouped into four groups with roughly equal numbers of K awardees, based on total amount of NIH funding received, as previously defined in detail in Jagsi R, Motomura AR, Griffith KA, Rangarajan S, Ubel PA. Sex differences in attainment of independent funding by career development awardees. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:804-811.

NIH funding institutes (e.g., National Cancer Institute, National Institute for Mental Health) ranked based on the dollar amount of R01 grants awarded and then grouped into those awarding the highest amount of funding (first), those in the middle (second), and those awarding the least (third), as previously defined in detail in Jagsi R, Motomura AR, Griffith KA, Rangarajan S, Ubel PA. Sex differences in attainment of independent funding by career development awardees. Ann Intern Med. 20091;151:804-811.

Table 3 presents multivariate models of salary in the sample: a full model including all theoretically selected covariates and a parsimonious reduced model. The gender effect was similar in both models (+$10,921 for men in the full model and +$10,663 for men in the reduced model). Of note, we observed one statistically significant interaction between gender and a modeled covariate. This significant interaction was between gender and specialty pay level (P < 0.001), and the interaction remained significant when modeled simultaneously with the main effects in the model, revealing the gender difference in salary in this sample to be larger in the higher-paying specialties.

Table 3. A Parsimonious Model of Self-Reported Annual Salary of Early Career Physician-Researchers (N = 1,012) Holding Academic Positions in Clinical Specialties Who Received National Institutes of Health (NIH) Mentored Career Awards from 2006 – 2009: Multivariate Model.

| Characteristic | All covariates | Reduced model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salary estimate in U.S. $ | P value | Salary estimate in U.S. $ | P value | |

| Intercept | 129,665 | < 0.001 | 124,631 | < 0.001 |

| Gender | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| Men | 10,921 | 10,663 | ||

| Women | Reference | Reference | ||

| 1-year increase in age (centered at 40) | -772 | 0.08 | -976 | 0.02 |

| Self-reported race | 0.110 | |||

| White | Reference | |||

| Black | -13,591 | |||

| Asian | 5,272 | |||

| Other | -2,518 | |||

| Marital status | 0.85 | |||

| Married | Reference | |||

| Divorced/widowed | -1,034 | |||

| Single/never married | -3,598 | |||

| Parental status | 0.13 | 0.03 | ||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | ||

| No | -5,987 | -7,605 | ||

| Additional PhD degree/s | 0.74 | |||

| Yes | -1,081 | |||

| No | Reference | |||

| Academic rank | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| Fellow/research scientist | -57,752 | -53,128 | ||

| Instructor | -22751, | -23,965 | ||

| Assistant professor | Reference | Reference | ||

| Associate professor | 16,877 | 18,008 | ||

| Full professor | 31,410 | 35,477 | ||

| 1-year increase in number of years on faculty (centered at 4) | 1,257 | 0.11 | 1,668 | 0.02 |

| Specialty | 0.292 | |||

| Medical specialties | Reference | |||

| Clinical specialties for women, children, and families | -117 | |||

| Hospital-based (e.g., emergency, anesthesiology, pathology, and radiology) | -4,296 | |||

| Surgical specialties | 10,511 | |||

| Specialty pay level* | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| Low-paying | Reference | Reference | ||

| Moderately-paying | 17,299 | 18,609 | ||

| High-paying | 49,075 | 50,776 | ||

| Extremely high-paying | 136,656 | 143,688 | ||

| K award institution type | 0.085 | |||

| Public | Reference | |||

| Private | 5,781 | |||

| K award institution NIH funding tier† | 0.06 | |||

| First | -12,690 | |||

| Second | -8,234 | |||

| Third | -6,021 | |||

| Fourth | Reference | |||

| K award institution region | 0.55 | |||

| West | -1,353 | |||

| Midwest | -475 | |||

| South | -6,591 | |||

| Northeast | Reference | |||

| K award type | 0.79 | |||

| K08 | -816 | |||

| K23 | Reference | |||

| Years since receipt of K award | 0.63 | |||

| 4 | 2,056 | |||

| 3 | Reference | |||

| 2 | -3,128 | |||

| 1 | -1,988 | |||

| Funding institute tier‡ | 0.44 | |||

| First | 4,660 | |||

| Second | 2,108 | |||

| Third | Reference | |||

| 1-hour increase in number of hours spent working (centered at 58) | 419 | 0.002 | 454 | < 0.001 |

| 1-percentage point increase in percentage of time spent conducting research (centered at 68) | -298 | < 0.001 | -299 | < 0.001 |

Based on salaries as reported in the Association of American Medical Colleges Faculty Salary Survey Reports, which are available through www.aamc.org/publications. Examples of specialties within each category are as follows: extremely high paying = neurosurgery and radiology; high paying = emergency medicine and gastroenterology; moderately paying = neurology and pathology; low paying = pediatrics and family medicine.

Institutions ranked and then grouped into four groups with roughly equal numbers of K awardees, based on total amount of NIH funding received, as previously defined in detail in Jagsi R, Motomura AR, Griffith KA, Rangarajan S, Ubel PA. Sex differences in attainment of independent funding by career development awardees. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:804-811.

NIH funding institutes (e.g., National Cancer Institute, National Institute for Mental Health) ranked based on the dollar amount of R01 grants awarded and then grouped into those awarding the highest amount of funding (first), those in the middle (second), and those awarding the least (third), as previously defined in detail in Jagsi R, Motomura AR, Griffith KA, Rangarajan S, Ubel PA. Sex differences in attainment of independent funding by career development awardees. Ann Intern Med. 20091;151:804-811.

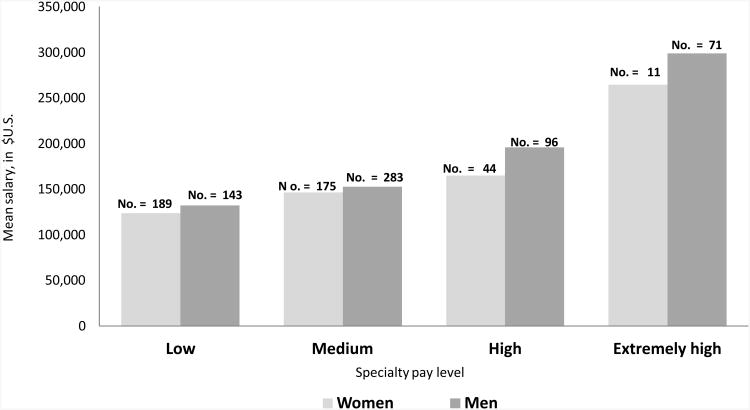

Specifically, as depicted in Figure 2, the mean salary for women in low-paying specialties (e.g., pediatrics, family medicine) was $123,678, whereas for men in these specialties, mean salary was $132,058. The mean salary for women in medium-paying specialties (e.g., neurology, pathology) was $146,651 versus $152,622 for men in these same medium-paying specialties. The mean salary for women in the high-paying specialties (e.g., emergency medicine, gastroenterology) was $165,114, and the mean salary for men in these specialties was $195,771. Finally, the mean salary for women in extremely high-paying specialties (e.g., neurosurgery, radiology) was $264,636, and the mean salary for men in these specialties was $298,915.

Figure 2.

Gender differences in salary, by specialty pay level. This graph depicts the mean self-reported current annual salaries of male and female physicians in a sample of 1012 physicians, by specialty pay level. The authors observed a statistically significant interaction between gender and specialty pay level, in which gender differences were most pronounced in the highest-paying specialties (e.g., neurosurgery, radiology).

Table 4 describes respondents' perceptions regarding their salaries. Respondents were more likely to indicate that compensation depended heavily upon grant funding than upon clinical volume (P < 0.001, Stuart-Maxwell test). There were no statistically significant gender differences in response to questions asking how much the respondent's compensation depended on clinical volume or number of patients seen (P = 0.13) or upon grant funding received (P = 0.41). However, men were more likely to report that their families were “very much” dependent upon their incomes to maintain an acceptable lifestyle than were women (77.5% vs 54.1%), and the difference was significant (P = 0.002) even after adjusting for spouse/partner employment status.

Table 4. Perceptions Regarding Salary of Early Career Physician-Researchers (N = 1,012) Holding Academic Positions in Clinical Specialties Who Received National Institutes of Health Mentored Career Awards from 2006 – 2009.

| Question | Gender | No. of people responding to the question | No. (%*) answering… | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Not at all | Somewhat | Moderately | Very much | |||

| How dependent is your family upon your income to maintain an acceptable lifestyle?† | Women | 383 | 21 (5.5) | 75 (19.6) | 80 (20.9) | 207 (54.1) |

|

|

||||||

| Men | 564 | 7 (1.2) | 42 (7.5) | 78 (13.8) | 437 (77.5) | |

|

| ||||||

| How much does your compensation depend upon clinical volume or the number of patients you see? | Women | 419 | 186 (44.4) | 147 (35.1) | 63 (15.0) | 23 (5.5) |

|

|

||||||

| Men | 593 | 253 (42.7) | 193 (32.6) | 91 (15.4) | 56 (9.4) | |

|

| ||||||

| How much does your compensation depend upon the amount of grant funding you receive? | Women | 418 | 72 (17.2) | 91 (21.8) | 78 (18.7) | 177 (42.3) |

|

|

||||||

| Men | 592 | 125 (21.1) | 125 (21.1) | 114 (19.3) | 228 (38.5) | |

Percentages may not equal 100 due to rounding.

Sample is limited to those that are married or in a domestic partnership or that have children (n = 947).

Peters-Belson analysis in the married/partnered subsample revealed that women earned less than what would be expected if they retained their other measured characteristics but were men. When we excluded spousal employment status from the Peters-Belson analysis, 17% of the total observed gender difference was unexplained by the other measured characteristics. When we did include spousal employment status, the proportion of the total gender difference in salary that remained unexplained was 10%. Thus, inclusion of a measure of spousal employment status explained only about a third of the previously unexplained gender difference.

Discussion

In this cohort of elite, early-career physician researchers who only recently commenced their faculty careers, we observed a substantial gender difference in salary that was not fully explained by specialty, academic rank, work hours, or even spousal employment. These findings suggest that salary disparities in academic medicine exist even in cohorts hired recently and that these disparities arise early in the course of a career. In a previous study of mid-career K award recipients, we observed similar gender differences in all specialties,1 but the gender difference in this study primarily existed in the higher-paying specialties (Figure 2). Thus, the salary gap appears to develop early in the career trajectory, especially for women in those specialties.

Scholars have noted that gender differences in salary that exist early in a career are likely to widen over time, and that the initial salary negotiation may merit particular attention.22,23 Some evidence suggests that women negotiate salary less aggressively than men do.24-28 Other, related research indicates that female academic physicians may need to prepare in advance for a conversation regarding salary in order to feel more comfortable being assertive during the negotiation and more self-confident afterwards.29 Additional research shows that women are judged more harshly than men for initiating negotiations. 30-33

Workshops in negotiation for women faculty are an increasingly common intervention that offices dedicated to the support of women at various academic institutions are pursuing.34-36 Given these current findings, such programs should consider expanding eligibility and outreach to ensure that female residents and fellows experience negotiation training prior to their first faculty appointments. Even with such training, however, new junior faculty are hardly in a position to ensure their own salary equity. Those doing the hiring and setting the salaries need to be sensitized both to the corrosive impact of salary inequity on faculty morale and to the importance of working to avoid even small inequities early in women's careers, particularly given evidence that such inequities grow over time.37 To that end, bias literacy workshops and other systematic educational interventions targeting department chairs, division chiefs, and medical school administrators merit further development and investigation.

In this study, we found that about one-third of the gender difference in salary that was unexplained by other factors could be explained by spousal employment. An unconscious influence of gender-linked beliefs about the “family wage” has been proposed as a mechanism underlying gender differences in salaries, despite the very high rates of women's labor force participation nationally.10 Our findings are consistent with this speculation; that is, the idea of the family wage may partially explain salary inequity among physician-researchers. Employers may feel that men who are supporting a family deserve higher salary than women whom they do not view (and who may not view themselves) as principal breadwinners. Given the large differences in family composition between men and women physicians (that is, women generally have partners who are employed full-time while men generally do not), salary-setting may possibly be influenced by extra-professional assumptions about gender, rather than by actual credentials or performance. Unobserved differences in activity at work (e.g., working a schedule that is equal in number of hours but more convenient for family life), not adequately addressed by control variables for work hours and research time are also possible explanations, although this seems less likely, given our selection of a relatively homogeneous and research-intensive population of academic medical faculty for this study. Future research, particularly employing qualitative methods, is necessary to explore further whether some of the observed salary differences result from differences in unmeasured aspects of job flexibility. After all, women may be more willing than their male colleagues to trade salary for flexibility; likewise, men may not perceive themselves to be as closely monitored at work as women do and are therefore more able to harness job flexibility without trading salary.

Even with the inclusion of spousal employment status in our model, an unexplained gender difference remained. Scholars of economics and of psychology have proposed various explanations for why gender differences in salaries may exist. Employers may exercise “statistical discrimination” when they set salaries, making inferences based upon group rather than individual characteristics38; in other words, an employer might pay a woman who works long hours a lower salary because of an assumption that women in general work fewer hours than men do. Unconscious gender biases may also influence employers,39-42 particularly when considering employees who are mothers.43,44 To the extent that we found a substantial gender difference that is not explained by numerous theoretically selected covariates (i.e., factors such as specialty, rank, work hours, and research time) these explanations merit attention.

Of note, even some of the difference that was explained by covariates in our model may warrant concern and attention. As in our previous work,1 specialty was a key driver of the overall difference in salary. Whether salary differences related to gender differences in specialization are justifiable depends upon whether women freely choose lower-paying specialties or whether they are discouraged from higher-paying specialties and whether the feminization of a specialty itself leads to lower pay.5

This study has a number of strengths. We obtained a high response rate—from an elite and homogeneous population in whom gender differences in salary would not be expected. Our questionnaire included specific items measuring a large number and variety of mechanisms that might underlie gender differences in salary. Several limitations also merit acknowledgment. All survey studies must confront concerns about possible selection bias; in this case, it is reassuring that we obtained a high response rate and found no gender difference between the initially targeted population and respondents. In addition, our measures draw from self-report, making them vulnerable to recall or other biases. Nevertheless, we developed these measures with standard techniques of survey design, including cognitive pretesting, 14 and the items have strong face validity.

In sum, this study suggests that gender differences in the compensation of physicians in academic medicine exist in cohorts hired recently who are still at the early stages of their careers. Some of the gender difference in salary appears to be explained by differences in spousal employment status, suggesting important mechanistic roles for differences in the behavior of physicians themselves and/or disparate treatment by employers. The residual unexplained gender difference suggests that other mechanisms are also important, including the possibility of conscious and unconscious bias. Efforts to ensure gender equity in physician pay should consider these findings and focus interventions accordingly, with particular attention towards transparent, consistent methods for determining pay at the institutional level.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the K-award recipients who took the time to participate in this study.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by Grant 5 R01 HL101997-04 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to Dr. Jagsi. The funding agency played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Dr. Ubel was also supported by grants from the NIH and by a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Investigator Award in Health Policy Research.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

Footnotes

Other disclosures: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dr. Reshma Jagsi, Center for Bioethics and Social Sciences in Medicine, Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Mr. Kent A. Griffith, Center for Cancer Biostatistics, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Dr. Abigail Stewart, Department of Psychology, Women's Studies Program, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Ms. Dana Sambuco, Center for Bioethics and Social Sciences in Medicine, Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Ms. Rochelle DeCastro, Center for Bioethics and Social Sciences in Medicine, Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Dr. Peter A. Ubel, Fuqua School of Business, Sanford School of Public Policy, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina.

References

- 1.Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Stewart A, Sambuco D, DeCastro R, Ubel PA. Gender differences in the salaries of physician researchers. JAMA. 2012;307:2410–2417. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ash AS, Carr PL, Goldstein R, Friedman RH. Compensation and advancement of women in academic medicine: Is there equity? Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:205–212. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-3-200408030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaplan SH, Sullivan LM, Dukes KA, Phillips CF, Kelch RP, Schaller JG. Sex differences in academic advancement: Results of a national study of pediatricians. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1282–1289. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610243351706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kehrer BH. Factors affecting the incomes of men and women physicians: An exploratory analysis. J Hum Resour. 1976;11:526–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright AL, Schwindt LA, Bassford TL, et al. Gender differences in academic advancement: Patterns, causes, and potential solutions in one U.S. college of medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78:500–508. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200305000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ness RB, Ukoli F, Hunt S, et al. Salary equity among male and female internists in Pennsylvania. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:104–110. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-2-200007180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weeks WB, Wallace TA, Wallace AE. How do race and sex affect the earnings of primary care physicians? Health Aff. 2009;28:557–566. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DesRoches CM, Zinner DE, Rao SR, Lezzoni LI, Campbell EG. Activities, productivity, and compensation of men and women in the life sciences. Acad Med. 2010;85:631–639. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d2b095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LoSasso AT, Richards MR, Chou C, Gerber SE. The $16,819 pay gap for newly trained physicians: The unexplained trend of men earning more than women. Health Aff. 2011;30:193–201. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrett M, Mcintosh M. The 'family wage': some problems for socialists and feminists. Capital and Class. 1980;4:51–72. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institutes of Health. [Accessed July 28, 2011];Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools. http://projectreporter.nih.gov/reporter.cfm.

- 12.Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method. 3rd. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.UM ADVANCE Program. [Accessed July 19, 2013];University of Michigan survey of academic climate and activities. Available at http://www.advance.rackham.umich.edu/climatesurvey1.pdf.

- 14.Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jagsi R, Motomura A, Griffith K, et al. Sex differences in attainment of independent funding by career development awardees. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:804–811. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Multimodel inference: understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociological Methods & Research. 2004;33:261–304. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters CC. A method of matching groups for experiment with no loss of population. Journal of Educational Research. 1941;34:606–612. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belson WA. A technique for studying the effects of a television broadcast. Applied Statistics. 1956;5:195–202. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao RS, Graubard BI, Breen N, Gastwirth JL. Understanding the factors underlying disparities in cancer screening rates using the Peters-Belson approach. Med Care. 2004;42:789–800. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000132838.29236.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oaxaca R. Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. Int Econ Review. 1973;14:693–709. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blinder AS. Wage discrimination: Reduced form and structural estimates. J Human Resources. 1973;8:436–455. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerhart B. Gender differences in current and starting salaries: The role of performance, college major, and job title. Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 1990;43:418–433. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowles HR, Babcock L, McGinn KL. Constraints and triggers: Situational mechanics of gender in negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:951–965. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stuhlmacher AF, Walters AE. Gender differences in negotiation outcome: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology. 1999;52:653–677. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bear J. “Passing the Buck”: Incongruence between gender role and topic leads to avoidance of negotiation. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research. 2011;4:47–72. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Small DA, Gelfand M, Babcock L, Gettman H. Who goes to the bargaining table? The influence of gender and framing on the initiation of negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:600–613. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.4.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Babcock L, Laschever S. Ask for it: How women can use the power of negotiation to get what they really want. New York, NY: Batnam Books; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambuco D, Dabrowska A, DeCastro R, Stewart A, Ubel PA, Jagsi R. Negotiation in academic medicine: Narratives of faculty researchers and their mentors. Acad Med. 2013;88:505–511. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318286072b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarfaty S, Kolb D, Barnett R, et al. Negotiation in academic medicine: A necessary career skill. Journal of Women's Health. 2007;16:235–244. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowles HR, Babcock L, Lai L. Social incentives for gender differences in the propensity to initiate negotiations: Sometimes it does hurt to ask. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 2007;103:84–103. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolb DM. Too bad for the women or does it have to be? Gender and negotiation research over the past 25 years. Negotiation Journal. 2009;25:515–531. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tinsley CH, Cheldelin SI, Kupfer Schneider A, Amanatullah ET. Women at the bargaining table: Pitfalls and prospects. Negotiation Journal. 2009;25:233–249. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wade ME. Women and salary negotiation: The costs of self-advocacy. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2001;25:65–76. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johns Hopkins Medicine. The Office of Women in Science and Medicine. [Accessed July 19, 2013];Programs and Lectures, Information and Conversation Sessions. Available at http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/education/women_science_medicine/programs_lectures.html.

- 35.Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania. [Accessed July 19, 2013];FOCUS on Health & Leadership for Women, Overview of Initiatives. Available at http://www.med.upenn.edu/focus/user_documents/OverviewFOCUSInitiatives_Final_10.16.12.pdf.

- 36.Brigham and Women's Hospital Center for Faculty Development & Diversity. [Accessed July 19, 2013];Office for Women's Careers. Available at: http://www.brighamandwomens.org/Medical_Professionals/career/CFDD/OWC/Images/OWCExternalBrochure_2010reprint.pdf.

- 37.Gerhart B, Rynes S. Determinants and consequences of salary negotiations by graduating male and female MBAs. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1991;76:256–262. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldin C. Understanding the Gender Gap: An Economic History of American Women. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Academy of Sciences; National Academy of Engineering; Institute of Medicine, Committee on Maximizing the Potential of Women in Academic Science and Engineering. Beyond Bias and Barriers: Fulfilling the Potential of Women in Academic Science and Engineering. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steinpreis RE, Anders KA, Ritzke D. The impact of gender on the review of the curricula vitae of job applicants and tenure candidates: A national empirical study. Sex Roles. 1999;41:509–528. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heilman ME, Eagly AH. Gender stereotypes are alive, well, and busy producing workplace discrimination. Industrial and Organizational Psychology. 2008;1:393–398. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phelan JE, Moss-Racusin CA, Rudman LA. Competent yet out in the cold: Shifting criteria for hiring reflect backlash toward agentic women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2008;32:406–413. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benard S, Correll SJ. Normative discrimination and the motherhood penalty. Gender and Society. 2010;24:616–646. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Correll SJ, Benard S, Paik I. Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? Am J Sociol. 2007;112:1297–1338. [Google Scholar]