Abstract

Liver X receptors (LXRs) are nuclear hormone receptors that regulate cholesterol and fatty acid metabolism in liver tissue and in macrophages. Although LXR activation enhances lipogenesis, it is not well understood whether LXRs are involved in adipocyte differentiation. Here, we show that LXR activation stimulated the execution of adipogenesis, as determined by lipid droplet accumulation and adipocyte-specific gene expression in vivo and in vitro. In adipocytes, LXR activation with T0901317 primarily enhanced the expression of lipogenic genes such as the ADD1/SREBP1c and FAS genes and substantially increased the expression of the adipocyte-specific genes encoding PPARγ (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ) and aP2. Administration of the LXR agonist T0901317 to lean mice promoted the expression of most lipogenic and adipogenic genes in fat and liver tissues. It is of interest that the PPARγ gene is a novel target gene of LXR, since the PPARγ promoter contains the conserved binding site of LXR and was transactivated by the expression of LXRα. Moreover, activated LXRα exhibited an increase of DNA binding to its target gene promoters, such as ADD1/SREBP1c and PPARγ, which appeared to be closely associated with hyperacetylation of histone H3 in the promoter regions of those genes. Furthermore, the suppression of LXRα by small interfering RNA attenuated adipocyte differentiation. Taken together, these results suggest that LXR plays a role in the execution of adipocyte differentiation by regulation of lipogenesis and adipocyte-specific gene expression.

Adipocyte differentiation, called adipogenesis, is a complex process accompanied by coordinated changes in morphology, hormone sensitivity, and gene expression. These changes are regulated by several transcription factors, including C/EBPs, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), and ADD1/SREBP1c (44, 67). These transcription factors interact with each other to execute adipocyte differentiation, including lipogenesis and adipocyte-specific gene expression, which are pivotal for metabolism in adipocytes. Expression of C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ occurs at a very early stage of adipocyte differentiation, and overexpression of C/EBPα or C/EBPβ promotes adipogenesis through cooperation with PPARγ (15, 32, 68, 69). PPARγ, a member of the nuclear hormone receptor family, is predominantly expressed in brown and white adipose tissue (58, 59). PPARγ is activated by fatty acid-derived molecules such as prostaglandin J2 and synthetic thiazolidinediones (TZDs), novel drugs used in type II diabetes treatment (14, 25, 29). Recent studies involving PPARγ knockout mice indicated that the major roles of PPARγ are adipocyte differentiation and insulin sensitization (3, 26, 43). ADD1/SREBP1c, which also appears to be involved in adipocyte differentiation, is highly expressed in adipose tissue and liver and is also expressed early in adipocyte differentiation (22, 60). ADD1/SREBP1c stimulates the expression of several lipogenic genes, including FAS, LPL, ACC, SCD-1, and SCD-2 (22, 55). Furthermore, ADD1/SREBP1c expression is modulated by the nutritional status of animals and is regulated in an insulin-sensitive manner in fat and liver (13, 17, 23, 49). Therefore, it is likely that ADD1/SREBP1c plays major roles in both fatty acid and glucose metabolism to orchestrate energy homeostasis.

Adipocytes are highly specialized cells that play a critical role in energy homeostasis. The major role of adipocytes is to store large amounts of lipid metabolites during periods of energy excess and to utilize these depots during periods of nutritional deprivation (12, 52). Adipocytes also function as endocrine cells by secreting several adipocytokines that regulate whole-body energy metabolism (34, 35, 47). Adipocytes possess the full complement of enzymes and regulatory proteins required to execute both de novo lipogenesis and lipolysis. These two biochemical processes are tightly controlled and determine the rate of lipid storage in adipocytes. Disorders of lipid metabolism involving fatty acid and cholesterol are associated with obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases (10, 35, 53). To maintain lipid homeostasis, higher organisms have developed regulatory networks involving fatty acid- or cholesterol-sensitive nuclear hormone receptors, such as PPARs (PPARα, PPARδ, and PPARγ), retinoid X receptors (RXRs), farnesoid X receptor, and liver X receptors (LXRα and LXRβ) (6).

Recent data suggest that among nuclear hormone receptors, LXRs play dynamic roles in the regulation of cholesterol and fatty acid metabolism. The LXR family consists of LXRα and LXRβ (33, 42, 50, 56, 66). LXRα is predominantly expressed in liver, adipose tissue, kidney, and spleen, whereas LXRβ is ubiquitously expressed (33, 66). LXRs are activated by naturally produced oxysterols, including 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol, 24,25(S)-epoxycholesterol, and 27-hydroxycholesterol, and by the synthetic compound T0901317 (18, 28, 48). LXRs form heterodimers with RXR that directly bind two direct repeat sequences (AGGTCA) separated by four nucleotides (DR4, also known as LXRE) (64-66). The major physiological role of LXRs appears to be as cholesterol sensors (39). LXRs regulate a set of genes associated with regulation of cholesterol catabolism, absorption, and transport (11, 33, 38, 61). In the intestine, activated LXRs decrease cholesterol absorption mediated by ATP-binding cassette (ABC) A1 (8, 40, 42, 51). In macrophages, the activation of LXRs induces cholesterol efflux by ABCA1, ABCG1, and apoE (5, 27, 62, 63). In the liver, LXRs regulate Cyp7A1, which regulates bile acid synthesis, the major route for cholesterol removal (28, 39, 48). In addition, a number of studies indicate that LXRs also regulate several genes involved in fatty acid metabolism by either modulating the expression of ADD1/SREBP1c or directly binding promoters of particular lipogenic genes, including FAS (2, 9, 19, 41, 48, 70). In support of these observations, LXRα/β-deficient mice show reduced expression of the FAS, SCD-1, ACC, and ADD1/SREBP1c genes, which are genes involved in fatty acid metabolism (39).

Liver and adipose tissues are considered major organs for the regulation of lipid metabolism. However, it is uncertain whether LXRs are directly involved in the process of adipocyte differentiation, including adipocyte-specific gene expression and adipogenesis. Very recently, it has been shown that LXR activation elevates lipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells with increased lipogenic gene expression (4, 20). In the present study, we have found that LXR activation is involved not only in lipogenesis but also in adipogenesis with adipocyte-specific gene expression through an increase of PPARγ expression. Activation of LXRs in several preadipocyte cell lines stimulated adipocyte differentiation with an increase of lipogenesis. LXR activation with T0901317 preferentially increased the expression of lipogenic genes such as ADD1/SREBP1c and FAS and enhanced the expression of adipocyte-specific genes such as the PPARγ and aP2 genes in vivo and in vitro. In addition, we found that PPARγ is a novel target of LXRα. Furthermore, suppression of LXRα by small interfering RNA (siRNA) inhibited adipocyte differentiation. These observations suggest that LXRs are involved in both lipid metabolism and adipocyte differentiation in fat tissue.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and adipocyte differentiation.

3T3-L1 preadipocytes were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum (BCS) at 10% CO2 and 37°C. Differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells was induced as described previously (22). Briefly, confluent cells were incubated for 2 days in a medium comprising DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 0.5 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, 1 μM dexamethasone, and 5 μg of insulin/ml. Thereafter, medium was replaced every other day with DMEM containing 10% FBS and 5 μg of insulin/ml. Primary human stromal vascular cells (HSVCs) were obtained from subcutaneous adipose tissue. Written informed consent was obtained from the subjects involved in the study. Briefly, subcutaneous adipose tissue was washed with phosphate-buffered saline. A washed tissue sample was treated with 0.075% collagenase for 30 min at 37°C with mild agitation. Cell pellets were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in DMEM with 10% FBS, and then cells were filtered through 100-μm mesh and filtrated HSVCs were used for experiments. HSVCs were induced into adipocyte as described above for the differentiation protocol for 3T3-L1 cells. h293 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% BCS and cultured at 37°C in a 10% CO2 incubator. The mouse embryo fibroblast (MEF) cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS-1 mM pyruvate (1 mmol/liter)-1% nonessential amino acid modified Eagle's medium-2 mM β-mercaptoethanol and cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Differentiation of MEF cells was induced as described previously (31).

Microarray.

Total RNA was isolated from preadipocytes and fully differentiated 3T3-F442A adipocytes. The preparation of cDNA, hybridization, and the scanning of mouse chips were performed according to the manufacturer's protocols (Genocheck Co., Kyunggi-do, Korea). Arrays were scanned with a GenePix 4000 microarray scanner (Axon).

Northern blot and RT-PCR analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from mouse tissues and cultured cells by using Trizol (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Twenty micrograms of total RNA was denatured in formamide and formaldehyde, separated in formaldehyde-containing agarose gels, transferred to Nytran membranes (Schleicher and Schuell, Dassel, Germany), and then cross-linked, hybridized, and washed according to the protocol recommended by the membrane manufacturer. cDNA probes were radiolabeled by random priming by using the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I (Promega) and [α-32P]dCTP (6,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham-Pharmacia). LXRα, ADD1/SREBP1c, FAS, PPARγ, and aP2 cDNAs were used as probes. To determine the evenness of RNA loading, all blots were hybridized with a cDNA probe for human acidic ribosomal protein 36B4. Reverse transcription (RT)-PCRs were performed with the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen) by using 250 ng of total RNA. SCD-1, ADD1/SREBP1c, aP2, PPARγ, and GAPDH cDNAs were amplified for 30, 30, 30, 35, and 25 cycles, respectively, and these PCRs did not result in saturation. RT-PCR products were separated by 0.7% agarose gel electrophoresis, and band intensities were analyzed by imaging of ethidium bromide stains (Scion Image). Primers used in this study were as follows: SCD-1-f, 5′-TGG GTT GGC TGC TTG TG-3′; SCD-1-r, 5′-GCG TGG GCA GGA TGA AG-3′; ADD1/SREBP1c-f, 5′-GGG AAT TCA TGG ATT GCA CAT TTG AA-3′; ADD1/SREBP1c-r, 5′-CCG CTC GAG GTT CCC AGG AAG GGT-3′; aP2-f, 5′-CAA AAT GTG TGA TGC CTT TGT G-3′; aP2-r, 5′-CTC TTC CTT TGG CTC ATG CC-3′; PPARγ-f, 5′-TTG CTG AAC GTG AAG CCC ATC GAG G-3′; PPARγ-r, 5′-GTC CTT GTA GAT CTC CTG GAG CAG-3′; GAPDH-f, 5′-TGC ACC ACC AAC TGC TTA G-3′; GAPDH-r, 5′-GGA TGC AGG GAT GAT GTT C-3′.

Cloning of the mouse PPARγ promoter and construction of a luciferase reporter.

Mouse genomic DNA was isolated from 3T3-L1 cells with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 50 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]). The PCR reaction mixture contained each primer at 2 mM, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at 0.6 mM, 1× PCR buffer, and 5 U of LA Taq polymerase (TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan) in a 50-μl reaction volume. The PCR cycle consisted of 40 s at 95°C, followed by 30 cycles of 20 s at 95°C, 40 s at 55°C, and 3 min at 72°C, followed by 5 min at 72°C. The primers used were pPPARγ-f (at bp −1022), 5′-GTC ACT GAA TTA TAT TAG GTA CCT TAT GTG ACA AGG GCT-3′, and pPPARγ-r (at bp +26), 5′-TCA GCG AAG GCA CCA TGC TCT GGG TCA ACT CGA GAA TCT C-3′. The primers included KpnI (5′ primer) and XhoI (3′ primer) restriction sites. The PCR products were digested with KpnI and XhoI, cloned into pGEM easy vector (Promega), and subcloned into pGL3-basic vector (Promega). Site-directed mutagenesis of the mouse pPPARγ −1,022-LXRE-Luc plasmid was performed with the QuikChange kit (Stratagene) by using the following mutagenic primers (mutated sites underlined): pPPARγ −1,022-mLXRE-Luc, 5′-CAG TGA ATG TGT GGG CCA CTG GCC AGA GAA TGT AGC AAC G-3′; pPPARγ −1,022-mLXRE-Luc-γ, 5′-CGT TGC TAC ATT CTC TGG CCA GTG GCG CAC ACA TTC ACT G-3′.

Transient transfection and luciferase assay.

h293 cells were cultured as described above and transfected 1 day prior to reaching confluence by the calcium phosphate method as described previously (21). Cells were transfected with luciferase reporter plasmid (100 ng/well), each nuclear hormone receptor expression plasmid (250 ng/well), and pCMVβ-galactosidase (50 ng/well). Following transfection, cells were incubated in DMEM containing 10% delipidated BCS and vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) or T0191317 (1 μM) for 24 h. Mammalian expression vectors for LXRα and RXRα were derived from the pCMX vector as described previously (66). Total cell extracts were prepared by using a lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-phosphate [pH 7.8], 2 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM 1,2-diaminocyclohexane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100), and the activities of β-galactosidase and luciferase were determined according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). Luciferase activity in relative light units was normalized to β-galactosidase activity for each sample.

siRNA for LXRα.

The sequences of the oligonucleotides used to create pSUPER-Retro-siLXRα were as follows: siLXRαSR933-f, 5′-GAT CCC CAC AGC TCC CTG GCT TCC TAT TCA AGA GAT AGG AAG CCA GGG AGC TGT TTT TTG GAA A-3′; siLXRαSR933-r, 5′-AGC TTT TCC AAA AAA CAG CTC CCT GGC TTC CTA TCT CTT GAA TAG GAA GCC AGG GAG CTG TGG G-3′; siLXRαSR1246-f, 5′-GAT CCC CGT AGA GAG GCT GCA ACA CAT TCA AGA GAT GTG TTG CAG CCT CTC TAC TTT TTG GAA A-3′; siLXRαSR1246-r, 5′-AGC TTT TCC AAA AAG TAG AGA GGC TGC AAC ACA TCT CTT GAA TGT GTT GCA GCC TCT CTA CGG G-3′. The oligonucleotides were synthesized and purified by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. These oligonucleotides were annealed and cloned into pSUPER-Retro vector (OligoEngine). The constructs were transfected into BOSC cells by the calcium phosphate method. After transfection, cells were incubated in DMEM containing 10% FBS for 48 h. The cell culture medium was filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter, and the viral supernatant was used for the infection of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes after the addition of 4 μg of Polybrene/ml. The cells were infected for at least 12 h and allowed to recover for 24 h with fresh medium. Infected cells were selected with puromycin at 1 to 5 μg/ml for 10 days. siRNA experiments were carried out as described by the manufacturer (OligoEngine).

EMSA.

For the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), each plasmid DNA expressing LXRα or RXRα (1 μg) was used as a template for in vitro translation. In order to measure translation efficiencies for the different plasmid templates, l-[35S]methionine was included in separate reactions and radiolabeled proteins were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The DNA sequence of double-stranded oligonucleotides for the probe was as follows (only one strand is shown): LXRE, 5′-GTG TGG GTC ACT GGC GAG ACA ATG-3′. The LXRE oligonucleotide was end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase, and 0.1 pmol (∼30,000 cpm) was used as a probe in 20 μl of a binding reaction mixture containing 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.05 mM EDTA, 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, 8.5% (vol/vol) glycerol, 1 mg of poly(dI-dC), 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.1% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk for each reaction. Samples were loaded onto a nondenaturing 4% polyacrylamide gel. Gels were dried and autoradiographed. For binding competition analysis, unlabeled oligonucleotides (100-fold molar excess) were added to the reaction mixture just prior to the addition of the radiolabeled probe. The DNA sequences of the double-stranded oligonucleotides were as follows (only one strand is shown): SRE, 5′-GAT CCT GAT CAC CCC ACT GAG GAG-3′; Cyp7A1 LXRE, 5′-CCT TTG GTC ACT CAA GTT CAA GTG-3′.

ChIP assay.

For the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay, differentiated adipocytes were incubated in the absence or presence of LXR's agonist, T0901317 (10 μM), for 24 h. These cells were cross-linked in 1% formaldehyde at 37°C for 10 min and resuspended in 200 μl of NP-40-containing buffer (5 mM PIPES) [piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid)] [pH 8.0], 85 mM KCl, 0.5% NP-40). The crude nuclei were precipitated and lysed in 200 μl of lysis buffer (1% SDS, 10 mM EDTA, 0.01% SDS, 1.1% Triton X-100). Lysates were incubated with protein A-Sepharose CL-4B (Amersham-Pharmacia) and either specific LXRα antibodies or histone H3 acetylation-detecting antibodies for 12 h at 4°C. The immunoprecipitates were successively washed for 5 min each with 1 ml of TSE 150 (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.1], 150 mM NaCl), 1 ml of TSE 500 (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.1], 500 mM NaCl), 1 ml of buffer III (0.25 M LiCl, 1% NP-40, 1% deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.1]), and 1 ml of TE (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA). Immune complexes were eluted with 2 volumes of 250 μl of elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3), and 20 μl of 5 M NaCl was added to reverse formaldehyde cross-linking. DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform and precipitated with isopropyl alcohol and 80 μg of glycogen. Precipitated DNA was amplified by PCR. The mixture for PCRs consisted of each primer at 0.25 μM, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at 0.1 mM, 1× PCR buffer, 1 U of Ex Taq polymerase (TaKaRa), and 0.06 mCi of [α-32P]dCTP/ml in a 20-μl reaction volume. PCR products were resolved in 8% polyacrylamide-1× Tris-borate-EDTA gels. Primers used in this study were as follows: −247 ADD1/SREBP1c-f, 5′-AGC CAC CGG CCA TAA ACC AT-3′; +56 ADD1/SREBP1c-r, 5′-GGT TGG TAC CAC AGT GAC CG-3′; −349 PPARγ-f, 5′-CTG TAC AGT TCA CGC CCC TC-3′; −51 PPARγ-r, 5′-TCA CAC TGG TGT TTT GTC TAT G-3′;GAPDH-f, 5′-GTG TTC CTA CCC CCA ATG TG-3′; GAPDH-r, 5′-CTT GCT CAG TGT CCT TGC TG-3′.

Animal treatment.

Male C57BL/6 mice (12 weeks old, approximately 23 g each) were housed (5 mice/cage) and given water ad libitum, with a 12 h light-12 h dark cycle beginning at 7:00 a.m. These mice received intraperitoneal injections of either vehicle (control) or 50 mg of T0901317/kg of body weight/day for 1, 3, or 5 days. Four mice were injected with each treatment. T0901317 was dissolved in DMSO (50 mg/ml) and diluted (5:1) with 0.9% saline prior to injection (45, 48). Mice were sacrificed, and several types of tissue were isolated, including epididymal fat and liver.

RESULTS

Expression of LXR in differentiated adipocytes and white adipose tissue.

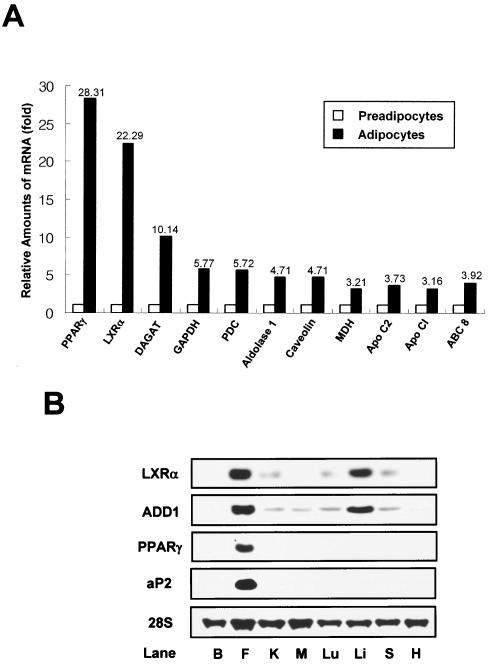

In order to understand transcription regulation during adipocyte differentiation, we examined gene expression profiles on a genome-wide scale. Total RNA for DNA microarray analysis was isolated from preadipocytes and fully differentiated 3T3-F442A adipocytes. Transcript levels indicated that 8.9% of the genes were induced more than twofold, while the expression of 6.9% of the genes was decreased more than 0.5-fold following adipocyte differentiation (unpublished data). Interestingly, there was a significant increase in the relative mRNA expression levels of 11 genes, namely, the PPARγ, LXRα, diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DAGAT), glutaraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), pyruvate decarboxylase (PDC), aldolase 1, caveolin, malate dehydrogenase (MDH), apolipoprotein 1 (Apo C1), Apo C2, and ABC 8 genes (Fig. 1A). Moreover, PPARγ and LXRα transcript levels were greatly increased (28- and 22-fold, respectively) in differentiated adipocytes compared to those in preadipocytes. Mouse LXRα mRNA tissue distribution was determined by Northern blot analysis. Expression was high in white adipose tissue and liver but low in kidney, lung, and spleen tissues (Fig. 1B). LXRβ was expressed in all tissues examined (data not shown), as previously indicated (33, 66). Notably, lipogenic genes such as ADD1/SREBP1c and FAS were also highly expressed in both fat and liver tissues, whereas adipocyte-specific genes such as PPARγ and aP2 were expressed predominantly in fat tissue (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that LXRs may play a role in adipocyte biology.

FIG. 1.

Expression of LXRα mRNA in adipocytes and mouse tissues. (A) Relative amounts of mRNA expression of adipogenic genes as determined by DNA microarray analysis. Total RNA was isolated from confluent preadipocytes and fully differentiated 3T3-F442A adipocytes and used for DNA microarray analysis. Relative amounts of mRNA expression of 11 genes are shown. Apo CI, apolipoprotein 1; Apo C2, apolipoprotein 2. (B) LXRα mRNA expression in C57BL/6 mouse tissues. Northern blot analysis was performed by using 20 μg of total RNA and cDNA probes for LXRα, ADD1/SREBP1c, PPARγ, aP2, and 36B4. B, brain; F, white adipose tissue (epididymal fat); K, kidney; M, muscle; Lu, lung; Li, liver; S, spleen; H, heart.

Activation of LXR promotes adipocyte differentiation with adipogenic gene expression.

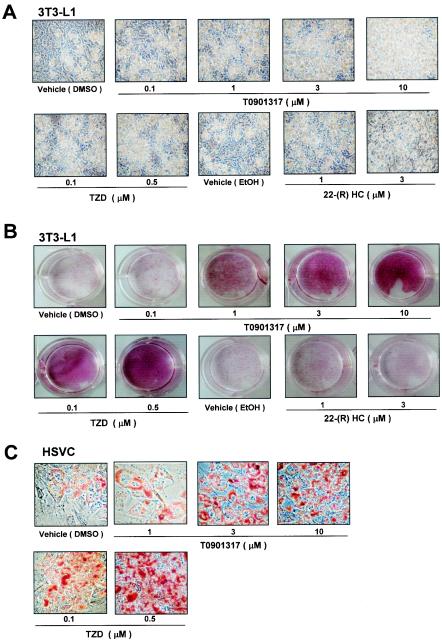

LXR expression profiles suggest a role in adipocyte differentiation or adipocyte functions, such as lipogenesis. To test this possibility, preadipocyte cells were treated with LXR agonists during differentiation. Treatment of the preadipocyte cell line, 3T3-L1, with the synthetic LXR agonist T0901317 or the endogenous ligand 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol resulted in markedly enhanced adipocyte differentiation, as determined by the accumulation of more and larger lipid droplets than in control cells (Fig. 2A and B). Similar to these results, the activation of LXR stimulated adipocyte differentiation, as determined by an increase of Oil Red O staining in primary HSVCs (Fig. 2C) or 3T3-F442A cells (data not shown). Previous studies showed that LXRα is a target gene for PPARγ, a potent adipogenic transcription factor (1, 5). PPARγ activation by its agonist TZD strongly promotes adipogenesis in preadipocytes and nonadipogenic cell lines (59). We examined the effect of TZD in our system and found that the treatment of cells with either T0901317 or TZD dose-dependently stimulated adipocyte phenotypes with large lipid droplets (Fig. 2). However, T0901317-activated LXRs were not as efficient at promoting adipocyte differentiation as TZD-activated PPARγ was, suggesting that LXR activation does not simply mimic the adipogenic action of PPARγ in adipocyte differentiation.

FIG. 2.

Adipogenic effect of LXR activation in preadipocytes. 3T3-L1 cells (A and B) and HSVCs (C) were differentiated into adipocytes in the presence or absence of the LXR agonist T0901317, 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol [22-(R) HC], or the PPARγ agonist TZD. (A and C) Microscopic pictures were taken 10 days after differentiation. (B and C) Differentiated adipocytes were stained with Oil Red O and photographed. EtOH, ethyl alcohol.

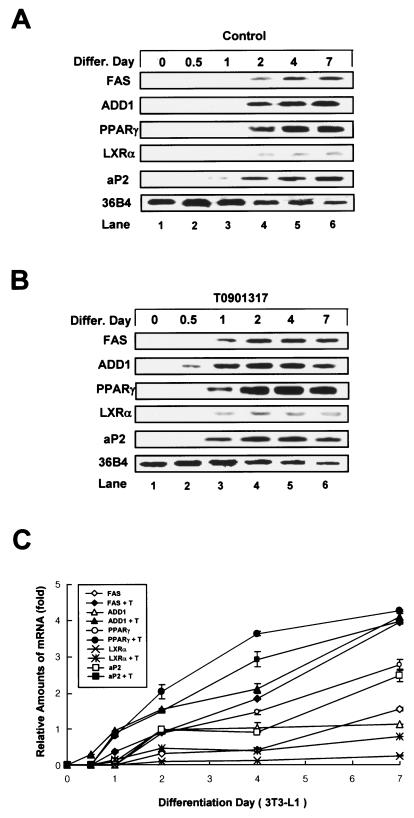

It is difficult to distinguish the differences between lipogenesis and adipogenesis in the process of adipocyte differentiation because adipocyte differentiation is accompanied by both lipogenesis and adipocyte-specific gene expression. For example, while lipogenesis actively occurs in several tissues, including fat and liver tissues, adipogenesis occurs only in fat cells, since adipocyte-specific gene expression is required for fat cell-specific functions such as the synthesis of adipocytokines. Although the activation of LXRs increased lipid droplet formation in 3T3-L1 cells, it has been suggested that activated LXRs might stimulate only lipogenesis and not adipogenesis (4, 20). Thus, we decided to investigate whether LXR activation is involved in bona fide adipocyte differentiation, as defined by increases of both lipogenesis and adipocyte-specific gene expression. 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were differentiated into adipocytes in the absence or presence of T0901317, and total RNA was isolated at different times and processed for Northern blotting. We found that the expression of adipocyte marker genes ADD1/SREBP1c, PPARγ, FAS, and aP2 began 2 to 3 days postconfluence in the absence of an exogenous activator (Fig. 3A). In contrast, those genes were expressed 1 to 2 days earlier in cells treated with T0901317 (Fig. 3B and C). Furthermore, their expression levels were increased compared to those of the control group (Fig. 3C). A similar pattern was observed at the protein level, as seen in anti-ADD1/SREBP1c and anti-PPARγ immunoblots (unpublished data). These results indicate that activated LXRs stimulate adipocyte differentiation per se, not only by enhancing the accumulation of cytosolic lipid droplets but also by increasing the expression of both lipogenic and adipocyte-specific genes during adipocyte differentiation.

FIG. 3.

Stimulation of adipogenic marker gene expression following LXR activation during adipocyte differentiation (differ.). (A and B) 3T3-L1 cells were differentiated into adipocytes in the absence (A) or presence (B) of T0901317 (3 μM), and cells were harvested at the indicated time points. Northern blots (20 μg of total RNA) were hybridized with FAS, ADD1/SREBP1c, PPARγ, LXRα, aP2, and 36B4 cDNA probes. (C) Data from panels A and B were quantified and normalized relative to the loading control to show relative mRNA expression. Experiments were independently repeated three times.

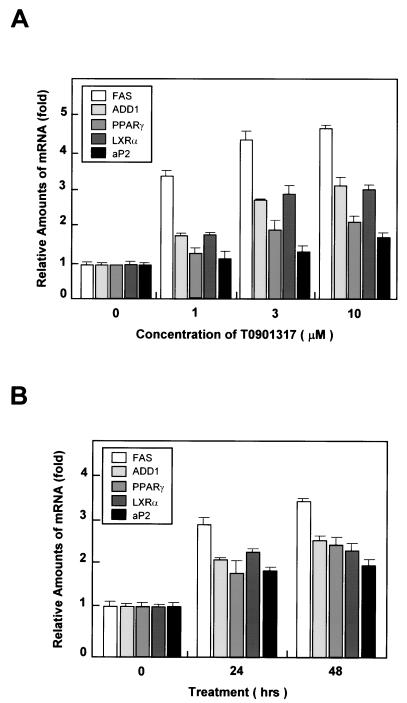

LXR activation preferentially regulates lipogenic gene expression in adipocytes.

To determine the function of activated LXRs in differentiated adipocytes, we investigated the expression of primary LXR target genes. Fully differentiated adipocytes were treated with T0901317 for various times, and gene expression profiles were determined by Northern blot analysis. The activation of LXRs significantly increased the expression of the lipogenic genes FAS and ADD1/SREBP1c in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 4). The expression of LXRα was also induced by T0901317 (Fig. 4), which is consistent with a recent report that oxysterol and synthetic LXR ligands induce the expression of LXRα mRNA (24). In addition, PPARγ and aP2 mRNA expression were induced by the addition of the LXR agonist (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Induction of lipogenic and adipogenic genes following acute LXR activation in differentiated adipocytes. (A) Differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes were treated with 0, 1, 3, or 10 μM T0901317 for 24 h. Northern blot analysis results were quantified and normalized relative to 28S rRNA levels. (B) 3T3-L1 adipocytes were treated for 0, 24, and 48 h with 3 μM T0901317, after which cells were harvested for Northern blot analysis. The results obtained were quantified and normalized relative to 28S rRNA levels. Northern blots (20 μg of total RNA) were hybridized with FAS, ADD1/SREBP1c, PPARγ, LXRα, and aP2 cDNA probes. Each experiment was independently repeated two times.

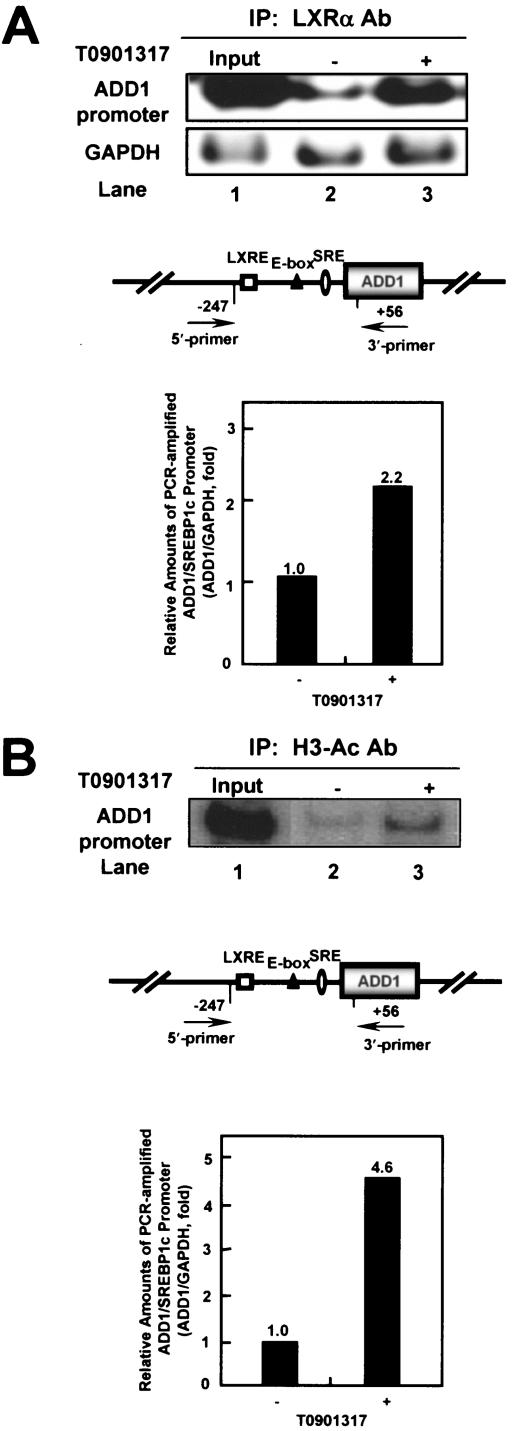

ADD1/SREBP1c is a key LXR target gene for the mediation of fatty acid metabolism in liver tissue (2, 9, 19, 36, 41, 48, 70). To determine whether activated LXRs increase the transcription of ADD1/SREBP1c through a change in its DNA binding ability, we performed ChIP analysis with adipocytes in the absence or presence of T0901317. Protein-DNA complexes were immunoprecipitated with antibodies against LXRα, and the recovered DNA fragments were analyzed by PCR. As shown in Fig. 5A, LXRα bound to endogenous chromatin DNA containing LXRE in the promoter region of the ADD1/SREBP1c gene. We also measured GAPDH gene fragments from the same immunoprecipitated DNA pellets to normalize the quantities of each PCR-amplified DNA as a background control. It is of interest that the activation of LXRα with T0901317 increased the ability of its DNA to bind to the endogenous promoter region of the ADD1/SREBP1c gene, implying that LXR-dependent transactivation for its target gene is probably mediated by enhanced DNA binding activity of LXR with its agonist. In addition, when T0901317 was treated, hyperacetylation of histone H3 was significantly induced in the same promoter region of the ADD1/SREBP1c gene, suggesting that activated LXRα would also stimulate ADD1/SREBP1c gene expression through chromatin modification, such as the hyperacetylation of histone H3 (Fig. 5B). Taken together, these results suggest that the activation of LXRs, particularly LXRα, potentiates ADD1/SREBP1c gene expression via elevated LXR-DNA interaction and hence regulates lipogenesis in adipocytes.

FIG. 5.

ChIP assay of mouse ADD1/SREBP1c promoter. Differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes were incubated in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 10 μM T0901317 for 24 h. Cells were cross-linked and immunoprecipitated with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against LXRα (LXRα Ab) (A) or polyclonal antibodies against acetylated histone H3 (H3-Ac Ab) (B). Immunoprecipitated DNA fragments were amplified by PCR (see Materials and Methods). Lane 1 shows the amplified mouse ADD1/SREBP1c promoter and GAPDH from 1% of the input DNA. GAPDH fragments were also amplified for the normalization of input DNA. PCR-amplified products of the mouse ADD1/SREBP1c promoter normalized with the amplified GAPDH fragments were quantitated. The putative sterol regulatory element (SRE; ellipse), LXRE (white square), and E-box (black triangle) are indicated. Data from a representative of three independent experiments are shown. IP, immunoprecipitant.

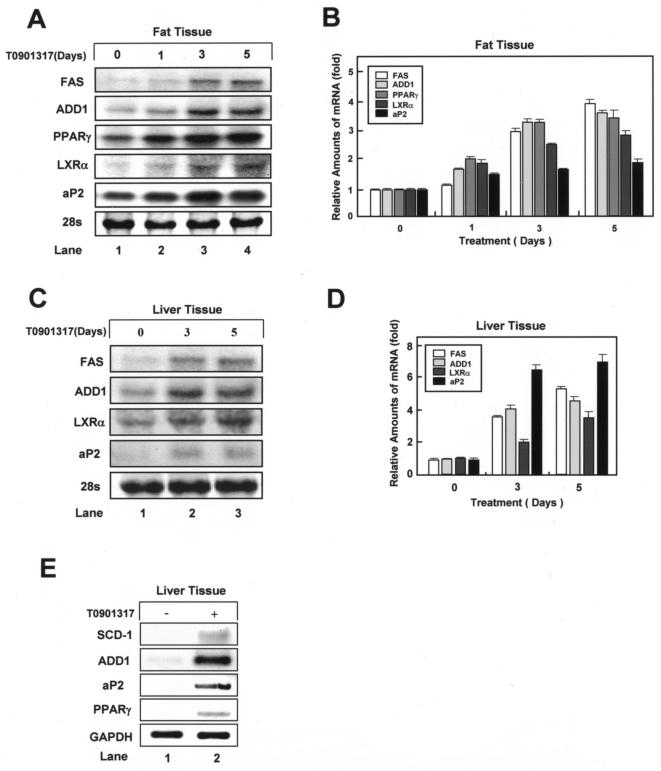

LXR activation stimulates both lipogenic and adipocyte-specific gene expression in white adipose tissue.

The functional role of LXRs in the regulation of fatty acid metabolism has been studied mainly for liver and hepatocytes (7, 16, 30, 33, 37, 46, 48, 54, 57). Although adipose tissue is also a major lipid metabolism organ, the effects of activated endogenous LXRs in this tissue in vivo have not been reported. We treated C57BL/6 mice with T0901317 for up to 5 days and examined adipocyte-specific and lipogenic gene expression in white adipose tissue and liver. In white adipose tissue, as in differentiated adipocytes, T0901317 treatment markedly increased the expression of lipogenic genes LXRα, FAS, and ADD1/SREBP1c (Fig. 6A and B). Notably, the mRNA levels of the adipocyte-specific genes PPARγ and aP2 also increased (Fig. 6A and B). These observations suggest that LXR activation in vivo stimulates the expression of both lipogenic and adipocyte-specific genes in white adipose tissue. In liver tissue, T0901317 increased the expression of several genes, such as ADD1/SREBP1c and FAS, involved in de novo lipogenesis (Fig. 6C and D). Unexpectedly, T0901317 treatment increased the expression of the adipocyte-specific marker gene aP2 in liver tissue, although much higher levels were observed in fat than in liver tissue (Fig. 6A, C, and E). This observation appears to be related to the progression of fatty liver induced by chronic LXR activation by T0901317, which would result in increased liver triglyceride levels (16). Since the expression of aP2 is regulated mainly by PPARγ, we examined the expression level of PPARγ in liver. Interestingly, LXR activation elevated the expression of PPARγ mRNA in liver (Fig. 6E). The above data support the hypothesis that LXR activation in vivo directly enhances lipid accumulation through the regulation of lipogenic gene expression and that LXR activation would stimulate adipogenesis with adipocyte-specific gene expression through the enhanced expression of the adipogenic transcription factor PPARγ in adipose tissue.

FIG. 6.

In vivo effects of LXR activation on adipogenic gene expression in white adipose tissue and liver. C57BL/6 mice were treated with T0901317 (50 mg/kg) or vehicle for 0, 1, 3, or 5 days. Epididymal fat and liver tissues were collected, and total RNA was isolated for Northern blotting (A and C) or RT-PCR analysis (E) to examine the mRNA expression of several genes, including the FAS, LXRα, ADD1/SREBP1c, PPARγ, and aP2 genes. (A) Expression in epididymal fat. (B) Data in panel A were quantified and normalized relative to 28S rRNA levels. (C and E) Expression in liver. (D) Data in panel C were quantified and normalized relative to 28S rRNA levels. Data from a representative of two independent experiments are shown.

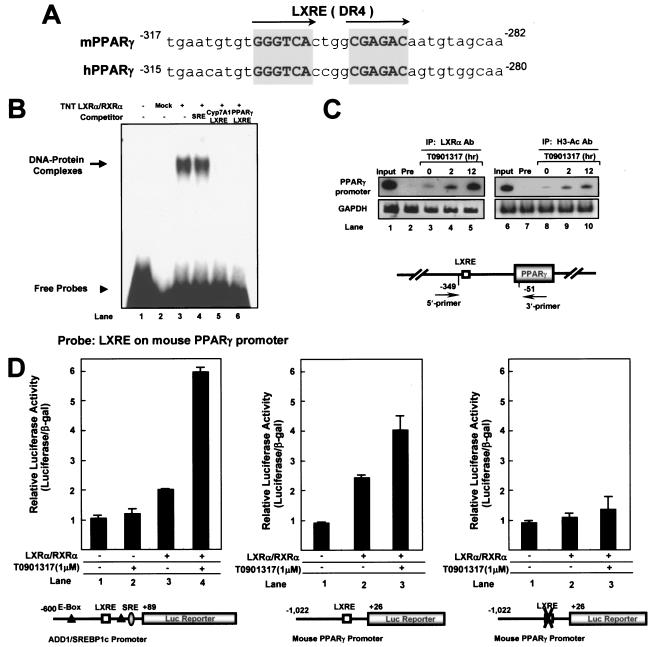

PPARγ is a novel target gene of LXRs.

As shown in Fig. 4 and 6, the activation of LXR promoted the expression of PPARγ and aP2 mRNA both in vitro and in vivo. These observations led us to investigate whether PPARγ is a novel target gene of LXRα. When the nucleotide sequence of the PPARγ promoter was analyzed, we found a conserved LXRE in the proximal promoter regions of both human and mouse PPARγ genes (Fig. 7A). Next, we used EMSA to examine whether activated LXRα binds directly to the PPARγ promoter. As shown in Fig. 7B, the LXRα/RXRα heterodimer bound to the LXRE motif in the PPARγ promoter in vitro in a sequence-specific manner. The protein-DNA complex was abolished by competition with unlabeled Cyp7A1 LXRE or PPARγ LXRE oligonucleotides (Fig. 7B, lanes 5 and 6). To further clarify that LXRα binds to the LXRE motif in the PPARγ promoter in vivo, we performed ChIP analysis. Differentiated adipocytes were incubated with or without T0901317 for different time periods. After cross-linking, DNA fragments were immunoprecipitated with antibodies against LXRα and amplified by PCR with the indicated primers (Fig. 7C). Similar to the results for ADD1/SREBP1c, the ability of the DNA of LXRα to bind to the PPARγ promoter was augmented in the presence of T0901317 (Fig. 7C). We also investigated the change in histone acetylation at the PPARγ promoter upon LXR activation because most of the activated nuclear hormone receptors are associated with the histone acetyltransferase complex. The acetylation of histone H3 was significantly increased in the PPARγ promoter region when adipocytes were treated with LXR agonist T0901317 (Fig. 7C). To test the idea that PPARγ is a novel target gene of LXRs, we performed a luciferase reporter assay with the mouse PPARγ promoter. In parallel, the activation of the ADD1/SREBP1c promoter by LXRα expression was examined as a positive control. As shown in Fig. 7D, the transcriptional activity of the PPARγ promoter was stimulated by the expression of LXRα. Furthermore, mutation of the LXRE motif in the same reporter construct abolished the transactivation by LXRα at the PPARγ promoter (Fig. 7D). Together, these results demonstrate that the PPARγ gene is a novel target gene of LXRα, which might induce the expression of the PPARγ gene via direct activation of the PPARγ promoter.

FIG. 7.

Direct binding of LXRα to the mouse PPARγ promoter. (A) Sequence comparison of putative LXREs (DR4) in mouse and human PPARγ promoters. (B) In vitro-translated LXRα and RXRα proteins were used for EMSA with 32P-labeled PPARγ LXRE oligonucleotide. Sequence-specific competition assays were performed with the addition of a 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled sterol regulatory element (SRE) (lane 4), Cyp7A1 LXRE (lane 5), and PPARγ LXRE (lane 6) oligonucleotides. (C) ChIP assays of the mouse PPARγ promoter. Differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes were incubated with (+) or without (−) LXR agonist T0901317 (10 μM) for 0, 2, or 12 h. Cells were cross-linked and immunoprecipitated with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against LXRα or polyclonal antibodies against acetylated histone H3. Immunoprecipitated DNA fragments were amplified by PCR (see Materials and Methods). Lane 1 shows the amplified mouse PPARγ promoter and GAPDH from 1% of the input DNA. GAPDH fragments were also amplified for the normalization of input DNA. IP, immunoprecipitant. (D) h293 cells were cotransfected with the pADD1/SREBP1c −600-Luc reporter DNA (100 ng/well) and expression vectors for LXRα and RXRα (lanes 3 and 4). pADD1/SREBP1c −600-Luc is a luciferase reporter containing the region comprising bp −600 to +89 of the mouse ADD1/SREBP1c promoter. In parallel, h293 cells were cotransfected with the mouse pPPARγ −1,022-LXRE-Luc reporter (wild-type) DNA (100 ng/well) or the mutant pPPARγ −1,022-mLXRE-Luc reporter DNA (100 ng/well) and expression vectors for LXRα and RXRα (lanes 2 and 3). The pPPARγ −1,022-LXRE-Luc reporter is a luciferase reporter containing bp −1022 to +26 of the mouse PPARγ promoter. The pPPARγ −1,022-mLXRE-Luc reporter is a luciferase reporter containing the mutation in the LXRE motif of the mouse PPARγ promoter. After transfection, cells were treated with (+) or without (−) LXR agonist T0901317 (10 μM) for 24 h.

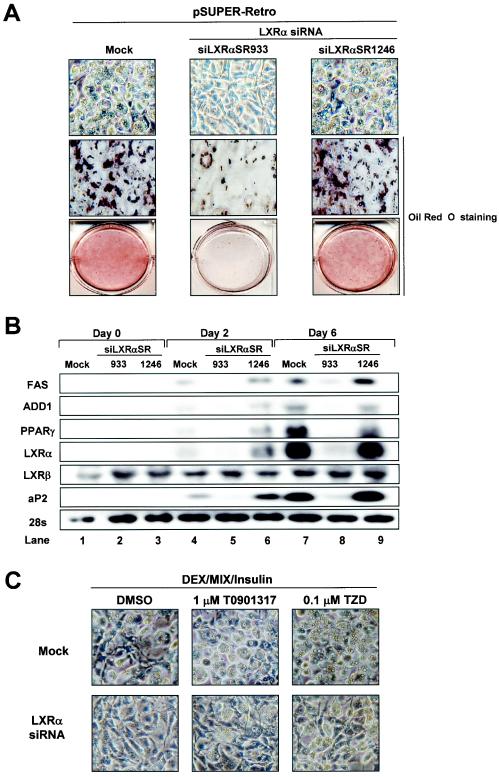

LXRα knockdown suppresses adipocyte differentiation.

To determine whether LXRs play a role in adipocyte differentiation, we attempted to knock down LXRα expression by retrovirus-derived siRNA, since LXRα is highly expressed in adipose tissue. We generated two different siRNA constructs, designated siLXRαSR933 and siLXRαSR1246. siLXRαSR933 potently suppressed the expression of LXRα mRNA, whereas siLXRαSR1246 failed to inhibit the expression of LXRα mRNA (data not shown). 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were infected with these retroviruses and were induced for adipocyte differentiation. As shown in Fig. 8A, siLXRαSR933-infected 3T3-L1 cells markedly repressed adipocyte differentiation, while empty retrovirus- or siLXRαSR1246-infected cells revealed normal adipocyte differentiation. To delineate whether the expression level of LXRα mRNA is critical for adipocyte differentiation, we conducted Northern blot analysis. We found that siLXRαSR933 efficiently suppressed the expression of endogenous LXRα mRNA but that siLXRαSR1246 or empty virus failed to knock down LXRα mRNA (Fig. 8B). Consistent with morphological changes, the knockdown of LXRα by siLXRαSR933 inhibited adipocyte-specific gene expression, including that of PPARγ and aP2 (Fig. 8B). When we generated stable cells expressing LXRα siRNA by using pSUPER vector in 3T3-L1, adipocyte differentiation was also dramatically attenuated (unpublished data). Although previous studies revealed that the LXRα gene is a target gene of PPARγ (1, 5), we showed here that the PPARγ gene would be a novel target gene of LXRα with a positive-feedback mechanism to execute adipocyte differentiation. To test whether the activation of PPARγ might induce adipogenesis in LXRα siRNA cells, we treated LXRα siRNA cells with TZD. TZD treatment partially, but not completely, compensated the differentiation potency of the LXRα siRNA cells, implying that the activation of LXRα is important for adipocyte differentiation as well as PPARγ activation (Fig. 8C). In addition, MEF cells derived from LXRα or LXRα/β knockout mice barely or slowly differentiated into adipocytes with normal hormonal induction, while MEF cells derived from LXRβ knockout mice normally differentiated into adipocytes like wild-type MEF cells (unpublished data). These data strongly suggest that LXRα is an important transcription factor for the mediation of adipocyte differentiation as well as adipogenic gene expression.

FIG. 8.

Effect of LXRα knockdown by siRNA during adipogenesis. 3T3-L1 cells were infected and selected with pSUPER retroviruses including mock, siLXRαSR933, and siLXRαSR1246 (see Materials and Methods). Those infected cells were differentiated into adipocytes and were harvested for total RNA preparation at the indicated time point. (A) The cells were stained with Oil Red O and photographed. (B) Northern blots (20 μg of total RNA) were hybridized with FAS, ADD1/SREBP1c, PPARγ, LXRα, LXRβ, and aP2 cDNA probes. Mock and siLXRαSR1246 were used as negative controls. (C) Effects of PPARγ ligand on 3T3-L1-LXRα siRNA stable cells. Mock and 3T3-L1-LXRα siRNA stable cell lines were differentiated into adipocytes under normal differentiation conditions (see Materials and Methods) in the absence (DMSO) or presence of T0901317 (1 μM) or rosiglitazone (0.1 μM).

LXRα activation cannot enhance adipogenesis in PPARγ-deficient MEF cells.

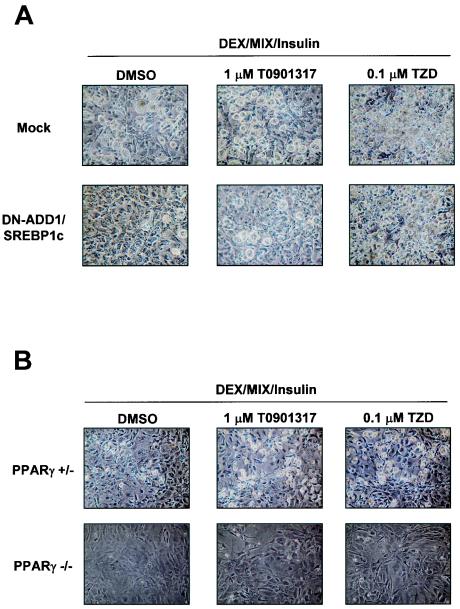

It is likely that LXRα is able to activate the expression of two different adipogenic transcription factors, ADD1/SREBP1c and PPARγ. To understand how LXRα enhances adipogenesis, we investigated the effect of LXRα activation on the adipocyte differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes stably expressing DN-ADD1/SREBP1c (the dominant-negative form of ADD1/SREBP1c) and MEF cells derived from PPARγ heterozygote or PPARγ knockout mice. As shown in Fig. 9A, retroviral overexpression of DN-ADD1/SREBP1c efficiently inhibited adipocyte differentiation and such an inhibitory effect of DN-ADD1/SREBP1c on adipocyte differentiation was relieved by TZD treatment, which is consistent with a previous report (23). In addition, the activation of LXR with T0901317 also rescued adipocyte differentiation in DN-ADD1/SREBP1c-expressing cells to a lesser extent than the activation of PPARγ by TZD, implying that LXRα-dependent enhancement of adipogenesis is partially mediated by ADD1/SREBP1c. On the other hand, adipogenesis of MEF cells derived from PPARγ knockout mice was not induced by the activation of LXRs, while MEF cells from the PPARγ hetrozygote mutant were differentiated into adipocytes more potently by TZD or T0901317 (Fig. 9B). These results imply that though both LXRα and PPARγ facilitate adipogenesis, they appear to participate in a unified pathway of adipocyte differentiation, with PPARγ being the proximal effector of adipogenesis.

FIG. 9.

Effects of LXR or PPARγ ligand on DN-ADD1/SREBP1c-expressing cells or PPARγ-deficient MEF cells. (A) 3T3-L1 cells were infected and selected with pBabe retroviruses including mock and DN-ADD1/SREBP1c. (B) MEF cells deficient in the PPARγ or the PPARγ heterozygote mutant or both of them were differentiated into adipocytes in the absence (DMSO) or presence of T0901317 (1 μM) or rosiglitazone (0.1 μM).

DISCUSSION

Both lipogenic and adipogenic gene expression are required for the execution of de novo adipogenesis. In the last decade, many laboratories have attempted to identify transcription factors which influence adipocyte differentiation. Here, we identified a novel mechanism of adipocyte differentiation with LXRs which affect both lipogenesis and adipocyte-specific gene expression. The idea that the activation of LXRs might be involved in adipocyte differentiation (or biology) has emerged from observations such as those showing that LXRα is highly expressed in adipose tissue (45, 54) and that the expression of LXRα mRNA is induced during adipocyte differentiation (Fig. 1). In accordance with these observations, investigations of genome-wide gene expression profiles revealed that the activation of LXRs alters the expression of many adipocyte marker genes, including leptin, lipoprotein lipase, and uncoupling protein 1, in fat tissue (45, 54, 71).

In our analysis of LXR activation during adipocyte differentiation, we confirmed earlier studies suggesting that LXR activation increases lipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells (Fig. 2). We also observed that LXR activation potentiated lipogenesis in another preadipocyte cell line, 3T3-F442A, and in primary human preadipocytes (Fig. 2). Interestingly, we revealed that activated LXRs not only induced lipogenesis involving the accumulation of lipid droplets but also promoted the expression of several adipocyte-specific marker genes, such as PPARγ and aP2, during adipocyte differentiation (Fig. 3 and 4). Since these two genes are key characteristic features of differentiated adipocytes, it is likely that the activation of LXRs facilitates genuine adipocyte differentiation including lipogenesis and adipocyte-specific gene expression, at least in vitro.

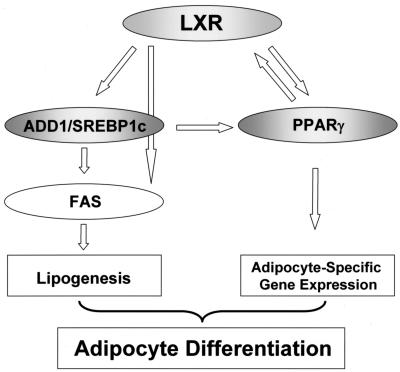

When the above idea was tested in vivo, T0901317 treatment in mice increased the expression of adipocyte-specific genes such as the PPARγ and aP2 genes and also stimulated that of lipogenic genes such as the LXRα, ADD1/SREBP1c, and FAS genes in fat and liver tissues (Fig. 6). Previously, it has been demonstrated that LXRα expression is regulated by the potent adipogenic transcription factor PPARγ (1, 5). However, we found that the PPARγ gene is a novel target gene of LXRα, and this finding might explain how LXRα cooperates with PPARγ to expedite adipogenesis. There are several lines of evidence to support this hypothesis. First, LXR activation substantially increased the expression of PPARγ mRNA in both differentiated adipocytes and white adipose tissue in vitro and in vivo, respectively (Fig. 4 and 6). Second, similarly, the expression level of PPARγ mRNA was enhanced with the LXR agonist in liver (Fig. 6). This observation provides a clue as to how LXR activation could elevate aP2 mRNA expression in liver, since PPARγ is a key transcription factor for aP2 gene expression (Fig. 6). Third, activated LXRα bound to endogenous chromatin DNA containing the PPARγ promoter with LXRE, which is well conserved in both mice and humans (Fig. 7). Fourth, not only did LXRα bind directly to the LXRE motif in the PPARγ promoter, but it also stimulated PPARγ promoter activity. Therefore, these results indicate that activated LXRs stimulate the expression of the PPARγ gene as a novel target gene with a positive-feedback loop, so that these two abundant adipocyte nuclear hormone receptors, LXRs and PPARγ, are both involved in adipocyte differentiation (Fig. 10).

FIG. 10.

Functional roles of LXR in adipocyte differentiation. Crosstalks between LXRs and other adipogenic transcription factors such as ADD1/SREBP1c and PPARγ would play key roles in the mediation of lipogenesis and adipocyte-specific gene expression during adipogenesis.

In support of the present findings, Juvet et al. (20) reported that LXR activation in 3T3-L1 cells increases adipocyte morphology such as lipid droplet accumulation and expression of the lipogenic FAS and ADD1/SREBP1c genes. Although normal development of fat tissues was found in young LXRα/β null mice, Juvet et al. noticed that both white and brown adipose tissue masses were significantly decreased in old LXRα/β null mice compared to those in wild-type mice (20). However, these authors proposed that increased adipocyte phenotypes following LXR activation might not be due to genuine adipogenesis. Instead, they suggested that the activation of LXRs would cause only the induction of lipogenic genes, implying that the function of LXRs in adipocytes is limited to the production of lipid droplets. However, these authors did not report on the expression of adipocyte-specific genes such as the PPARγ and aP2 genes following LXR activation during adipocyte differentiation. Thus, the conclusion reached by Juvet et al. has to be modified in view of the present results regarding the role of LXRs in adipogenesis. As described above, we found that LXR activation explicitly increased adipocyte-specific gene expression both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 3, 4, and 6), suggesting that LXR activation would affect both lipogenesis and adipogenesis.

In contrast to the present findings and those of others, Ross et al. recently suggested that the activation of LXRs might play a negative role in adipocyte differentiation (45). These authors demonstrated that ectopic expression of LXRα followed by the activation of its synthetic ligand suppressed adipogenesis. Thus, they proposed that LXRα activation in adipose tissue might be involved in lipolysis rather than lipogenesis, since LXR activation produced a decrease of lipid droplet accumulation in adipocytes (45). However, we demonstrated that the expression of most adipogenic and lipogenic genes was clearly stimulated by the activation of endogenous LXR in either preadipocytes or differentiated adipocytes in vitro (Fig. 2 to 4) and in white adipose tissue and liver in vivo (Fig. 6). One plausible explanation to reconcile these discrepancies is that the activation of both LXRα and LXRβ might be required for lipogenesis and adipogenic gene expression, because adipocyte differentiation was decreased when only LXRα was overexpressed. Further studies are necessary to reconcile these contradictory data.

To maintain certain levels of lipid metabolites in the whole body, there should be at least two controlling systems, one for sensing the levels of fatty acids and cholesterol and the other for modulating the absorption, synthesis, and catabolism of both of these lipids. Since adipose tissue is a primary organ for lipid homeostasis, obese patients and animal models frequently show lipid disorders such as hyperlipidemia, hypercholesterolemia, and arteriosclerosis due to abnormal lipid metabolism. Lipogenesis in adipocytes is controlled by two different transcription factor families, SREBPs and LXRs. Previously, it has been demonstrated that oxysterols derived from increased intracellular cholesterol are able to activate LXRs, leading to increased ADD1/SREBP1c expression in liver (9, 41, 70). Consistent with these results, we observed that the activation of LXR primarily induced the expression of lipogenic genes, including the LXRα, ADD1/SREBP1c, FAS, and SCD-1 genes, in adipocytes in vitro and in fat and liver tissue in vivo (Fig. 4 and 6), which would account for the increase of lipogenesis by LXR activation. ChIP experiments indicate that the activation of LXR with T0901317 enhanced its DNA binding activity to the promoter regions of target genes such as the ADD1/SREBP1c gene (Fig. 5). Furthermore, it is of interest that the activation of LXR is linked to chromatin modification, since there was an increase of histone H3 acetylation to stimulate the expression of ADD1/SREBP1c (Fig. 5). Similar results were obtained with the PPARγ promoter (Fig. 7), indicating that changes in histone acetylation probably occurred in promoter regions of LXR target genes in an activated-LXR-dependent manner.

In summary, we have identified a novel function of LXRs in adipocyte biology. LXR activation led to the induction of both lipogenesis and adipogenesis during adipocyte development in vitro and in vivo. Activated LXR stimulates adipogenesis not only by increasing the transcription of ADD1/SREBP1c, but also by inducing PPARγ. These results imply that LXRα might also constitute another regulatory cascade for the execution of adipogenesis (Fig. 10). Because PPARγ directly regulates LXRα (5), it is especially likely that LXRα and PPARγ activate adipogenesis with a positive-feedback loop, reinforcing the expression of each other. Furthermore, since LXR activation could not activate adipogenesis on its own without PPARγ, it seems that activated LXRs and PPARγ might act in a single pathway for adipogenesis, with PPARγ being the final effector of adipogenesis. It has been considered that LXR agonists might be beneficial for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia, since they can promote cholesterol efflux. However, it has been reported that they also cause hypertriglyceridemia with fatty liver in vivo (16, 19). This notion appears to be related to our results indicating that activated LXRs stimulated both lipogenesis and adipogenesis in vivo, which could eventually cause hyperlipidemia in the absence of tight regulation. In this sense, it would be advantageous to develop selective LXR antagonists that could specifically downregulate lipogenesis and/or adipogenesis without affecting cholesterol metabolism. Although the detailed mechanism by which LXRs regulate adipogenesis has yet to be determined, the present results suggest a novel mechanism of LXRs in lipogenesis and adipogenesis through PPARγ.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Hueng-Sik Choi and Heekyung Chung for critically reading the manuscript. We also thank Bruce M. Spiegelman and Evan Rosen for MEFs of PPARγ knockout mice.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Stem Cell Research Center of the 21st Century Frontier Research Program (grant SC13150), the Molecular and Cellular BioDiscovery Research Program (grant M1-0106-02-0003), and the 21st Century Frontier Projects-The National R&D Projects for Development of Novel Biological Modulators (grant CBM1-A300-001-1-0-1), Ministry of Science and Technology, Republic of Korea. This work was also supported in part by a grant from the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries to H. Kang, as well as by a grant from the Swedish Science Council to J.-Å. Gustafsson. J. B. Seo, W. S. Kim, J. Ham, H. Kang, and J. B. Kim are supported by a BK21 Research Fellowship from the Ministry of Education and Human Resources Development.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akiyama, T. E., S. Sakai, G. Lambert, C. J. Nicol, K. Matsusue, S. Pimprale, Y. H. Lee, M. Ricote, C. K. Glass, H. B. Brewer, Jr., and F. J. Gonzalez. 2002. Conditional disruption of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma gene in mice results in lowered expression of ABCA1, ABCG1, and apoE in macrophages and reduced cholesterol efflux. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:2607-2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amemiya-Kudo, M., H. Shimano, T. Yoshikawa, N. Yahagi, A. H. Hasty, H. Okazaki, Y. Tamura, F. Shionoiri, Y. Iizuka, K. Ohashi, J. Osuga, K. Harada, T. Gotoda, R. Sato, S. Kimura, S. Ishibashi, and N. Yamada. 2000. Promoter analysis of the mouse sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c gene. J. Biol. Chem. 275:31078-31085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barak, Y., M. C. Nelson, E. S. Ong, Y. Z. Jones, P. Ruiz-Lozano, K. R. Chien, A. Koder, and R. M. Evans. 1999. PPAR gamma is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Mol. Cell 4:585-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao, G., Y. Liang, C. L. Broderick, B. A. Oldham, T. P. Beyer, R. J. Schmidt, Y. Zhang, K. R. Stayrook, C. Suen, K. A. Otto, A. R. Miller, J. Dai, P. Foxworthy, H. Gao, T. P. Ryan, X. C. Jiang, T. P. Burris, P. I. Eacho, and G. J. Etgen. 2003. Antidiabetic action of a liver X receptor agonist mediated by inhibition of hepatic gluconeogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 278:1131-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chawla, A., W. A. Boisvert, C. H. Lee, B. A. Laffitte, Y. Barak, S. B. Joseph, D. Liao, L. Nagy, P. A. Edwards, L. K. Curtiss, R. M. Evans, and P. Tontonoz. 2001. A PPAR gamma-LXR-ABCA1 pathway in macrophages is involved in cholesterol efflux and atherogenesis. Mol. Cell 7:161-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chawla, A., J. J. Repa, R. M. Evans, and D. J. Mangelsdorf. 2001. Nuclear receptors and lipid physiology: opening the X-files. Science 294:1866-1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chawla, A., E. Saez, and R. M. Evans. 2000. “Don't know much bile-ology.” Cell 103:1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costet, P., Y. Luo, N. Wang, and A. R. Tall. 2000. Sterol-dependent transactivation of the ABC1 promoter by the liver X receptor/retinoid X receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 275:28240-28245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeBose-Boyd, R. A., J. Ou, J. L. Goldstein, and M. S. Brown. 2001. Expression of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c) mRNA in rat hepatoma cells requires endogenous LXR ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:1477-1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeFronzo, R. A. 1997. Insulin resistance: a multifaceted syndrome responsible for NIDDM, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and atherosclerosis. Neth. J. Med. 50:191-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards, P. A., H. R. Kast, and A. M. Anisfeld. 2002. BAREing it all: the adoption of LXR and FXR and their roles in lipid homeostasis. J. Lipid Res. 43:2-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flier, J. S. 1995. The adipocyte: storage depot or node on the energy information superhighway? Cell 80:15-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foretz, M., C. Pacot, I. Dugail, P. Lemarchand, C. Guichard, X. Le Liepvre, C. Berthelier-Lubrano, B. Spiegelman, J. B. Kim, P. Ferre, and F. Foufelle. 1999. ADD1/SREBP-1c is required in the activation of hepatic lipogenic gene expression by glucose. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:3760-3768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forman, B. M., P. Tontonoz, J. Chen, R. P. Brun, B. M. Spiegelman, and R. M. Evans. 1995. 15-Deoxy-delta 12,14-prostaglandin J2 is a ligand for the adipocyte determination factor PPAR gamma. Cell 83:803-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freytag, S. O., D. L. Paielli, and J. D. Gilbert. 1994. Ectopic expression of the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha promotes the adipogenic program in a variety of mouse fibroblastic cells. Genes Dev. 8:1654-1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grefhorst, A., B. M. Elzinga, P. J. Voshol, T. Plosch, T. Kok, V. W. Bloks, F. H. van der Sluijs, L. M. Havekes, J. A. Romijn, H. J. Verkade, and F. Kuipers. 2002. Stimulation of lipogenesis by pharmacological activation of the liver X receptor leads to production of large, triglyceride-rich very low density lipoprotein particles. J. Biol. Chem. 277:34182-34190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horton, J. D., Y. Bashmakov, I. Shimomura, and H. Shimano. 1998. Regulation of sterol regulatory element binding proteins in livers of fasted and refed mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:5987-5992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janowski, B. A., P. J. Willy, T. R. Devi, J. R. Falck, and D. J. Mangelsdorf. 1996. An oxysterol signalling pathway mediated by the nuclear receptor LXR alpha. Nature 383:728-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joseph, S. B., B. A. Laffitte, P. H. Patel, M. A. Watson, K. E. Matsukuma, R. Walczak, J. L. Collins, T. F. Osborne, and P. Tontonoz. 2002. Direct and indirect mechanisms for regulation of fatty acid synthase gene expression by liver X receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 277:11019-11025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juvet, L. K., S. M. Andresen, G. U. Schuster, K. T. Dalen, K. A. Tobin, K. Hollung, F. Haugen, S. Jacinto, S. M. Ulven, K. Bamberg, J.-Å. Gustafsson, and H. I. Nebb. 2003. On the role of liver X receptors in lipid accumulation in adipocytes. Mol. Endocrinol. 17:172-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim, J. B., P. Sarraf, M. Wright, K. M. Yao, E. Mueller, G. Solanes, B. B. Lowell, and B. M. Spiegelman. 1998. Nutritional and insulin regulation of fatty acid synthetase and leptin gene expression through ADD1/SREBP1. J. Clin. Investig. 101:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim, J. B., and B. M. Spiegelman. 1996. ADD1/SREBP1 promotes adipocyte differentiation and gene expression linked to fatty acid metabolism. Genes Dev. 10:1096-1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim, J. B., H. M. Wright, M. Wright, and B. M. Spiegelman. 1998. ADD1/SREBP1 activates PPARgamma through the production of endogenous ligand. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:4333-4337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim, S. W., K. Park, E. Kwak, E. Choi, S. Lee, J. Ham, H. Kang, J. M. Kim, S. Y. Hwang, Y. Y. Kong, K. Lee, and J. W. Lee. 2003. Activating signal cointegrator 2 required for liver lipid metabolism mediated by liver X receptors in mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:3583-3592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kliewer, S. A., J. M. Lenhard, T. M. Willson, I. Patel, D. C. Morris, and J. M. Lehmann. 1995. A prostaglandin J2 metabolite binds peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and promotes adipocyte differentiation. Cell 83:813-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kubota, N., Y. Terauchi, H. Miki, H. Tamemoto, T. Yamauchi, K. Komeda, S. Satoh, R. Nakano, C. Ishii, T. Sugiyama, K. Eto, Y. Tsubamoto, A. Okuno, K. Murakami, H. Sekihara, G. Hasegawa, M. Naito, Y. Toyoshima, S. Tanaka, K. Shiota, T. Kitamura, T. Fujita, O. Ezaki, S. Aizawa, T. Kadowaki, et al. 1999. PPAR gamma mediates high-fat diet-induced adipocyte hypertrophy and insulin resistance. Mol. Cell 4:597-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laffitte, B. A., J. J. Repa, S. B. Joseph, D. C. Wilpitz, H. R. Kast, D. J. Mangelsdorf, and P. Tontonoz. 2001. LXRs control lipid-inducible expression of the apolipoprotein E gene in macrophages and adipocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:507-512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lehmann, J. M., S. A. Kliewer, L. B. Moore, T. A. Smith-Oliver, B. B. Oliver, J. L. Su, S. S. Sundseth, D. A. Winegar, D. E. Blanchard, T. A. Spencer, and T. M. Willson. 1997. Activation of the nuclear receptor LXR by oxysterols defines a new hormone response pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 272:3137-3140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lehmann, J. M., L. B. Moore, T. A. Smith-Oliver, W. O. Wilkison, T. M. Willson, and S. A. Kliewer. 1995. An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR gamma). J. Biol. Chem. 270:12953-12956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liang, G., J. Yang, J. D. Horton, R. E. Hammer, J. L. Goldstein, and M. S. Brown. 2002. Diminished hepatic response to fasting/refeeding and liver X receptor agonists in mice with selective deficiency of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c. J. Biol. Chem. 277:9520-9528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin, F. T., and M. D. Lane. 1992. Antisense CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein RNA suppresses coordinate gene expression and triglyceride accumulation during differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Genes Dev. 6:533-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin, F. T., and M. D. Lane. 1994. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha is sufficient to initiate the 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation program. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:8757-8761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu, T. T., J. J. Repa, and D. J. Mangelsdorf. 2001. Orphan nuclear receptors as eLiXiRs and FiXeRs of sterol metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 276:37735-37738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohamed-Ali, V., J. H. Pinkney, and S. W. Coppack. 1998. Adipose tissue as an endocrine and paracrine organ. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 22:1145-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nadler, S. T., and A. D. Attie. 2001. Please pass the chips: genomic insights into obesity and diabetes. J. Nutr. 131:2078-2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ou, J., H. Tu, B. Shan, A. Luk, R. A. DeBose-Boyd, Y. Bashmakov, J. L. Goldstein, and M. S. Brown. 2001. Unsaturated fatty acids inhibit transcription of the sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c) gene by antagonizing ligand-dependent activation of the LXR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:6027-6032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pawar, A., J. Xu, E. Jerks, D. J. Mangelsdorf, and D. B. Jump. 2002. Fatty acid regulation of liver X receptors (LXR) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) in HEK293 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277:39243-39250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peet, D. J., B. A. Janowski, and D. J. Mangelsdorf. 1998. The LXRs: a new class of oxysterol receptors. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 8:571-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peet, D. J., S. D. Turley, W. Ma, B. A. Janowski, J. M. Lobaccaro, R. E. Hammer, and D. J. Mangelsdorf. 1998. Cholesterol and bile acid metabolism are impaired in mice lacking the nuclear oxysterol receptor LXR alpha. Cell 93:693-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plosch, T., T. Kok, V. W. Bloks, M. J. Smit, R. Havinga, G. Chimini, A. K. Groen, and F. Kuipers. 2002. Increased hepatobiliary and fecal cholesterol excretion upon activation of the liver X receptor is independent of ABCA1. J. Biol. Chem. 277:33870-33877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Repa, J. J., G. Liang, J. Ou, Y. Bashmakov, J. M. Lobaccaro, I. Shimomura, B. Shan, M. S. Brown, J. L. Goldstein, and D. J. Mangelsdorf. 2000. Regulation of mouse sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c gene (SREBP-1c) by oxysterol receptors, LXRalpha and LXRbeta. Genes Dev. 14:2819-2830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Repa, J. J., and D. J. Mangelsdorf. 2000. The role of orphan nuclear receptors in the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 16:459-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosen, E. D., P. Sarraf, A. E. Troy, G. Bradwin, K. Moore, D. S. Milstone, B. M. Spiegelman, and R. M. Mortensen. 1999. PPAR gamma is required for the differentiation of adipose tissue in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Cell 4:611-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosen, E. D., C. J. Walkey, P. Puigserver, and B. M. Spiegelman. 2000. Transcriptional regulation of adipogenesis. Genes Dev. 14:1293-1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ross, S. E., R. L. Erickson, I. Gerin, P. M. DeRose, L. Bajnok, K. A. Longo, D. E. Misek, R. Kuick, S. M. Hanash, K. B. Atkins, S. M. Andresen, H. I. Nebb, L. Madsen, K. Kristiansen, and O. A. MacDougald. 2002. Microarray analyses during adipogenesis: understanding the effects of Wnt signaling on adipogenesis and the roles of liver X receptor α in adipocyte metabolism. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:5989-5999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Russell, D. W. 1999. Nuclear orphan receptors control cholesterol catabolism. Cell 97:539-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saltiel, A. R. 2001. You are what you secrete. Nat. Med. 7:887-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schultz, J. R., H. Tu, A. Luk, J. J. Repa, J. C. Medina, L. Li, S. Schwendner, S. Wang, M. Thoolen, D. J. Mangelsdorf, K. D. Lustig, and B. Shan. 2000. Role of LXRs in control of lipogenesis. Genes Dev. 14:2831-2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shimano, H., N. Yahagi, M. Amemiya-Kudo, A. H. Hasty, J. Osuga, Y. Tamura, F. Shionoiri, Y. Iizuka, K. Ohashi, K. Harada, T. Gotoda, S. Ishibashi, and N. Yamada. 1999. Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 as a key transcription factor for nutritional induction of lipogenic enzyme genes. J. Biol. Chem. 274:35832-35839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song, C., J. M. Kokontis, R. A. Hiipakka, and S. Liao. 1994. Ubiquitous receptor: a receptor that modulates gene activation by retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:10809-10813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sparrow, C. P., J. Baffic, M. H. Lam, E. G. Lund, A. D. Adams, X. Fu, N. Hayes, A. B. Jones, K. L. Macnaul, J. Ondeyka, S. Singh, J. Wang, G. Zhou, D. E. Moller, S. D. Wright, and J. G. Menke. 2002. A potent synthetic LXR agonist is more effective than cholesterol loading at inducing ABCA1 mRNA and stimulating cholesterol efflux. J. Biol. Chem. 277:10021-10027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spiegelman, B. M., and J. S. Flier. 1996. Adipogenesis and obesity: rounding out the big picture. Cell 87:377-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stern, M. P. 1995. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The “common soil” hypothesis. Diabetes 44:369-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stulnig, T. M., K. R. Steffensen, H. Gao, M. Reimers, K. Dahlman-Wright, G. U. Schuster, and J.-Å. Gustafsson. 2002. Novel roles of liver X receptors exposed by gene expression profiling in liver and adipose tissue. Mol. Pharmacol. 62:1299-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tabor, D. E., J. B. Kim, B. M. Spiegelman, and P. A. Edwards. 1999. Identification of conserved cis-elements and transcription factors required for sterol-regulated transcription of stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 and 2. J. Biol. Chem. 274:20603-20610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Teboul, M., E. Enmark, Q. Li, A. C. Wikstrom, M. Pelto-Huikko, and J.-Å. Gustafsson. 1995. OR-1, a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily that interacts with the 9-cis-retinoic acid receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:2096-2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tobin, K. A., H. H. Steineger, S. Alberti, O. Spydevold, J. Auwerx, J.-Å. Gustafsson, and H. I. Nebb. 2000. Cross-talk between fatty acid and cholesterol metabolism mediated by liver X receptor-alpha. Mol. Endocrinol. 14:741-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tontonoz, P., E. Hu, R. A. Graves, A. I. Budavari, and B. M. Spiegelman. 1994. mPPAR gamma 2: tissue-specific regulator of an adipocyte enhancer. Genes Dev. 8:1224-1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tontonoz, P., E. Hu, and B. M. Spiegelman. 1994. Stimulation of adipogenesis in fibroblasts by PPAR gamma 2, a lipid-activated transcription factor. Cell 79:1147-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tontonoz, P., J. B. Kim, R. A. Graves, and B. M. Spiegelman. 1993. ADD1: a novel helix-loop-helix transcription factor associated with adipocyte determination and differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:4753-4759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tontonoz, P., and D. J. Mangelsdorf. 2003. Liver X receptor signaling pathways in cardiovascular disease. Mol. Endocrinol. 17:985-993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Venkateswaran, A., B. A. Laffitte, S. B. Joseph, P. A. Mak, D. C. Wilpitz, P. A. Edwards, and P. Tontonoz. 2000. Control of cellular cholesterol efflux by the nuclear oxysterol receptor LXR alpha. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:12097-12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Venkateswaran, A., J. J. Repa, J. M. Lobaccaro, A. Bronson, D. J. Mangelsdorf, and P. A. Edwards. 2000. Human white/murine ABC8 mRNA levels are highly induced in lipid-loaded macrophages. A transcriptional role for specific oxysterols. J. Biol. Chem. 275:14700-14707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wiebel, F. F., and J.-Å. Gustafsson. 1997. Heterodimeric interaction between retinoid X receptor alpha and orphan nuclear receptor OR1 reveals dimerization-induced activation as a novel mechanism of nuclear receptor activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:3977-3986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Willy, P. J., and D. J. Mangelsdorf. 1997. Unique requirements for retinoid-dependent transcriptional activation by the orphan receptor LXR. Genes Dev. 11:289-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Willy, P. J., K. Umesono, E. S. Ong, R. M. Evans, R. A. Heyman, and D. J. Mangelsdorf. 1995. LXR, a nuclear receptor that defines a distinct retinoid response pathway. Genes Dev. 9:1033-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu, Z., P. Puigserver, and B. M. Spiegelman. 1999. Transcriptional activation of adipogenesis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11:689-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu, Z., Y. Xie, N. L. Bucher, and S. R. Farmer. 1995. Conditional ectopic expression of C/EBP beta in NIH-3T3 cells induces PPAR gamma and stimulates adipogenesis. Genes Dev. 9:2350-2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yeh, W. C., Z. Cao, M. Classon, and S. L. McKnight. 1995. Cascade regulation of terminal adipocyte differentiation by three members of the C/EBP family of leucine zipper proteins. Genes Dev. 9:168-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yoshikawa, T., H. Shimano, M. Amemiya-Kudo, N. Yahagi, A. H. Hasty, T. Matsuzaka, H. Okazaki, Y. Tamura, Y. Iizuka, K. Ohashi, J. Osuga, K. Harada, T. Gotoda, S. Kimura, S. Ishibashi, and N. Yamada. 2001. Identification of liver X receptor-retinoid X receptor as an activator of the sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c gene promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:2991-3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang, Y., J. J. Repa, K. Gauthier, and D. J. Mangelsdorf. 2001. Regulation of lipoprotein lipase by the oxysterol receptors, LXRalpha and LXRbeta. J. Biol. Chem. 276:43018-43024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]