Background: Trp-188 plays a role in regulating the activity of nitric-oxide synthase (NOS).

Results: W188H mutation stabilizes a 420-nm intermediate by distorting the heme macrocycle.

Conclusion: The 420-nm intermediate is a hydroxide-bound ferric heme species with a tetrahydrobiopterin radical center.

Significance:The data provide the first evidence for a critical intermediate in NOS.

Abstract

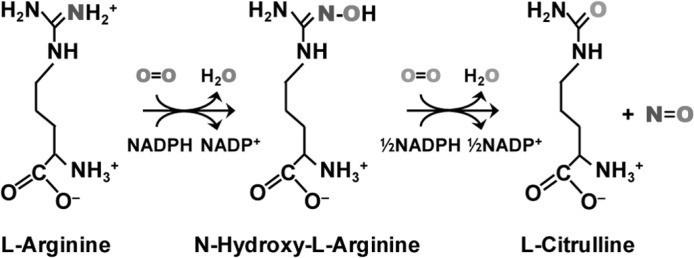

Nitric-oxide synthase (NOS) catalyzes nitric oxide (NO) synthesis via a two-step process: l-arginine (l-Arg) →N-hydroxy-l-arginine →citrulline + NO. In the active site the heme is coordinated by a thiolate ligand, which accepts a H-bond from a nearby tryptophan residue, Trp-188. Mutation of Trp-188 to histidine in murine inducible NOS was shown to retard NO synthesis and allow for transient accumulation of a new intermediate with a Soret maximum at 420 nm during the l-Arg hydroxylation reaction (Tejero, J., Biswas, A., Wang, Z. Q., Page, R. C., Haque, M. M., Hemann, C., Zweier, J. L., Misra, S., and Stuehr, D. J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33498–33507). However, crystallographic data showed that the mutation did not perturb the overall structure of the enzyme. To understand how the proximal mutation affects the oxygen chemistry, we carried out biophysical studies of the W188H mutant. Our stopped-flow data showed that the 420-nm intermediate was not only populated during the l-Arg reaction but also during the N-hydroxy-l-arginine reaction. Spectroscopic data and structural analysis demonstrated that the 420-nm intermediate is a hydroxide-bound ferric heme species that is stabilized by an out-of-plane distortion of the heme macrocycle and a cation radical centered on the tetrahydrobiopterin cofactor. The current data add important new insights into the previously proposed catalytic mechanism of NOS (Li, D., Kabir, M., Stuehr, D. J., Rousseau, D. L., and Yeh, S. R. (2007) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 6943–6951).

Nitric-oxide synthase (NOS) is a heme-containing flavoenzyme that synthesizes nitric oxide (NO) from l-arginine (l-Arg) in a two-step process (Scheme 1). In the first step of the reaction, one molecule of O2 and two electrons from NADPH are consumed for the conversion of l-Arg to N-hydroxy-l-arginine (NOHA).2 In the second step of the reaction, another molecule of O2 and an additional electron from NADPH are used to convert NOHA to l-citrulline and NO. Previous studies suggest that the two steps of the reaction follow distinct mechanisms meditated by a compound I (Cmpd I) type of ferryl intermediate and a peroxyl intermediate, respectively (1–7). These mechanisms, however, remain elusive, as none of the putative intermediates have been experimentally observed under solution conditions, although (hydro)peroxo intermediates have been identified at cryogenic temperatures by radiolytic reduction methods (8, 9); in addition, a Cmpd I intermediate has been observed after peroxyacid treatment (10).

Three isoforms of NOS have been identified in mammals: neuronal NOS, endothelial NOS, and inducible NOS (iNOS). Similar to the P450 class of enzymes, the heme prosthetic group in all three isoforms of NOS is coordinated by a thiolate sidechain group of an intrinsic cysteine residue in the proximal heme pocket. In P450s, the thiolate ligand forms a H-bond with a peptide NH group (11), whereas in NOSs the analogous thiolate ligand accepts a H-bond from the side chain of a conserved tryptophan residue (Trp-188 in iNOS). It is believed that the H-bonding interaction with the tryptophan residue reduces the electron donating capability of the thiolate ligand in NOSs, thereby modulating the oxygen chemistry occurring in the distal heme pocket of the enzymes (1, 12–15). The mutation of the conserved tryptophan (Trp-409) in neuronal NOS to Phe or Tyr was shown to increase the rate of NO synthesis during multiple turnover conditions by decreasing the heme reduction rate and the degree of NO autoinhibition (15, 16). Comparable mutants of iNOS, W188F, and W188Y, could not be overexpressed as stable recombinant forms (17); however, the W188H mutant was successfully expressed, purified, and studied (18).

It was shown that the W188H mutation slowed down the l-Arg hydroxylation reaction by stabilizing a new intermediate with a Soret maximum at 420 nm, which had never been observed during the wild type reaction, and that the formation of the 420-nm intermediate coincides with the disappearance of the ternary complex of the enzyme and the formation of a H4B radical, whereas its decay was concurrent with the recovery of the resting ferric enzyme. Tejero et al. (18) postulated that the 420-nm species is a catalytically competent oxygen-containing intermediate, such as a Cmpd I type of ferryl species. Regardless of the identity of the intermediate, the data demonstrated that the mutation modulates the structural properties and biochemical reactivity of the enzyme. However, the crystallographic data of the W188H mutant of the oxygenase domain of iNOS (iNOSoxy) revealed that its active site structure is strikingly similar to that of the wild type enzyme (18). In particular, the side chain of His-188, like that of Trp-188 in the wild type enzyme, formed a H-bond with the thiolate ligand of the heme.

To determine how the W188H mutation modulates the oxygen chemistry of iNOSoxy without significantly perturbing the active site structure of the enzyme, we carried out a series of studies of the W188H mutant with optical absorption, resonance Raman, and EPR spectroscopic methods under steady-state and single turnover conditions. We discovered that the mutation introduced a unique out-of-plane distortion to the heme macrocycle that stabilizes the 420-nm intermediate populated during both the l-Arg and NOHA reactions and at the same time destabilizes the NO bound to the ferric heme during the NOHA reaction. The results are summarized and discussed in the context of the previously postulated NOS mechanism (1).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

NOHA was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). H4B was purchased from Schircks Laboratories (Jona, Switzerland). Naturally abundant gases (N2 and O2) and liquid N2/He were purchased from Tech Air (White Plains, NY). Isotopically labeled gases (18O2 and 13C18O) were purchased from Icon (Summit, NJ). EPPS, arginine, citrulline, dithiothreitol (DTT), sodium dithionite, and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma. All chemicals were used without further purification and prepared with deionized water (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

All measurements were carried out with the oxygenase domain (residues 65–498) of murine iNOS (iNOSoxy), which was prepared as described earlier (19). Briefly, the iNOSoxy gene with a C terminus six-histidine tag was cloned into a pCWori vector and overexpressed in a BL-21 strain of Escherichia coli. The cells were lysed using a microfluidizer (Microfluidics Corp., Newton, MA) and purified in the absence of cofactor and substrate by a Qiagen nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity column (Germantown, MD). The purified enzyme was stored at 77 K in 40 mm EPPS buffer (pH 7.6) in the presence of 1 mm DTT. All purification steps were carried out at 4 °C, whereas the experimental measurements were done at 20 ± 1 °C unless otherwise indicated.

Optical Absorption Measurements—The optical absorption measurements were carried out on a UV2100 instrument from Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Inc. (Columbia, MD) with a spectral slit width of 1 nm. The path length of the optical cuvette was 2 mm. The protein concentrations were ∼5–10 μm. The substrate (l-Arg or NOHA) and cofactor (H4B) concentrations were at least 500-fold larger than the protein concentration unless otherwise indicated.

Stopped-flow Measurements—The stopped-flow measurements were carried out with a PiStar-180 system equipped with a photodiode array detector from Applied Photophysics Inc. (Leatherhead, UK). The enzyme, substrate, and cofactor were premixed and purged with N2 for ∼4 h in an airtight cuvette and subsequently titrated with a minimum amount of deoxy-genated sodium dithionite. The complete binding of substrate/cofactor and heme reduction was confirmed by optical absorption measurements. The reactions were initiated by 1:1 mixing of the ferrous enzyme (final concentration ∼5 μm) with air-saturated buffer. The data were analyzed with ProK software from Applied Photophysics Inc.

Resonance Raman Measurements—The equilibrium resonance Raman measurements were acquired with the system described previously (20). Briefly, the 413.1-nm output from a krypton ion laser (Spectra Physics, Mountain View, CA) was focused to an ∼30-μm spot on a quartz cuvette rotating at ∼1000 rpm. The scattered light was collected at a right angle to the incident beam and focused on a 100-μm entrance slit of a 1.25-m Spex spectrometer equipped with a 1200 grooves/mm grating (Horiba Jobin Yvon, Edison, NJ), where it was dispersed and detected by a liquid nitrogen-cooled charge-coupled device (CCD) detector (Princeton Instruments, Trenton, NJ). The incident laser light was removed by a holographic notch filter (Kaiser, Ann Arbor, MI). The Raman shifts were calibrated by using indene. Cosmic ray artifacts were removed using the Winspec software from Roper Scientific (Princeton, NJ). The laser power was <5 milliwatts at the sample for all measurements. The total integration time for each spectrum was 30 min. For the measurements of the CO related modes, the 441.6-nm laser output from a helium-cadmium laser (Kimmon, Centennial, CO) was used. The acquisition time for each spectrum was 30 min and 2 h for the measurements of the Fe-CO stretching mode (νFe-CO) and C-O stretching mode (νC-O), respectively. For the measurements of the iron-cysteine stretching mode (νFe-Cys), the 363.8 nm output from an argon laser (Spectra Physics, Mountain View, CA) was used. The acquisition time for these measurements was 1 h.

The continuous-flow resonance Raman measurements were carried out with a homemade continuous-flow apparatus as described elsewhere (21). The enzyme samples (80 μm) with l-Arg and/or H4B were purged with N2 gas for several hours before reduction with ∼2-fold excess of dithionite. The reduced enzyme and oxygen-saturated buffer (1.3 mm) were transferred to the homemade continuous-flow apparatus with gas-tight syringes (Hamilton, Reno, NV). The two solutions were mixed and flowed through a quartz cuvette (250-μm path length) at a rate of 3.3 ml/min. The progression of the reaction was probed by a laser beam at a desired time point. The scattered Raman light was collected perpendicular to the probe beam and measured as described above for the equilibrium measurements.

Rapid Freeze-Quench EPR Measurements—The EPR samples were prepared with a homemade rapid freeze-quench apparatus as described elsewhere (22). The dithionite-reduced enzyme (150 μm) with 10 mm l-Arg and 2 mm H4B was rapidly mixed with oxygen-saturated buffer at room temperature. The mixed solution jet was directed onto a liquid N2-cooled copper wheel, where it was instantly frozen and ground into a fine powder. The freeze-quenched samples were measured in a liquid N2-cooled finger Dewar with X-band EPR on a Varian E-line spectrometer at 77 K. The modulation amplitude, microwave power, and receiver gain was 1.6 G, 1 milliwatt, and 1.25 × 104, respectively. The microwave frequency was 9.105 GHz.

Variable temperature X-band (∼9 GHz) EPR spectra were measured with a Bruker ESP 300 spectrometer equipped with an ESR 10 continuous-flow cryostat (Oxford Instruments). The temperature was regulated by a 3120 temperature controller (Oxford Instruments). The temperature readout of the controller was calibrated using a Lakeshore Cernox Resistor immersed in glycerol in a 4-mm EPR tube that was placed in the EPR cavity at the position of the sample. Temperature uncertainty was estimated to be ± 1 K. D-band (130 GHz) EPR (two pulse echo-detected) measurements were carried out on a spectrometer described elsewhere (23, 24) at 7 K with 50-ns 90° pulses and 150 ns between pulses at a repetition rate of 30 Hz (30 averages per point). For both the X- and D-band measurements, the field was calibrated by Mn2+-doped MgO. Simulation of the X- and D-band spectra was performed using scripts written with MATLAB.

RESULTS

Optical Absorption and Raman Spectra of the Ferric Enzyme—To investigate how the W188H mutation affects the structural properties of the enzyme, we first characterize the ferric derivatives of the W188H mutant in the absence or presence of substrate (l-Arg or NOHA) and/or cofactor (H4B) with respect to the wild type (WT) enzyme with optical absorption spectroscopy. It is noted that a small amount of DTT (100 μm) was added to the H4B-containing samples to maintain H4B in the reduced state; the same amount of DTT was added to all other samples for consistency.

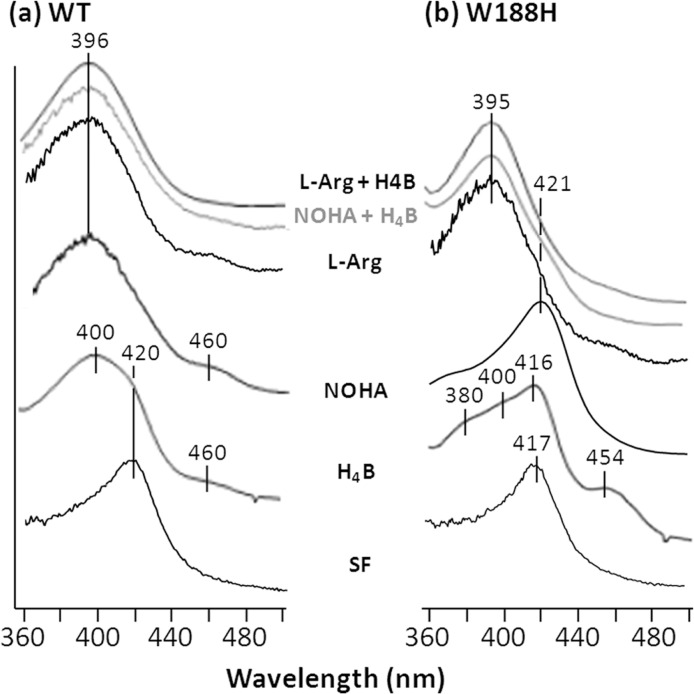

As reported previously (25), the wild type enzyme exhibits a Soret maximum at ∼420 nm, indicating a six-coordinate low spin (6CLS) heme with a water bound to the ferric heme iron (Fig. 1a). The binding of substrate (l-Arg or NOHA) and/or cofactor (H4B) to the enzyme introduced structural changes to it that destabilized the water ligand, thereby leading to a five-coordinate high spin (5CHS) heme, as indicated by the shift of the Soret maximum to ∼395–400 nm. The broad Soret band and weak shoulder at 460 nm indicate that a small amount of the enzyme has DTT bound to the heme iron as the distal ligand. The presence of a shoulder at ∼420 nm in the H4B-only sample indicates a minor contribution of the residual 6CLS water-bound ferric heme.

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of the optical absorption spectra of the ferric derivatives of the wild type enzyme (a) and the W188H mutant (b) of iNOSoxy. The solutions contain 10 μm enzyme in the presence or absence of 5 mm substrate and/or 5 mm cofactor (H4B) in 40 mm (pH 7.6) EPPS buffer containing 100 μm DTT. The bands at ∼460 nm are from the residual DTT-bound enzyme.

As in the wild type enzyme, the distal side of the ferric heme in the substrate and cofactor-free (SF) mutant enzyme was occupied by a water with a 6CLS configuration, as indicated by the Soret maximum at 417 nm (Fig. 1b); the binding of both substrate and cofactor (H4B + l-Arg or H4B + NOHA) or l-Arg alone destabilized the water ligand, leading to a 5CHS heme, as indicated by the shift of the Soret maximum to 395 nm. In contrast, the binding of either NOHA or H4B alone only slightly shifted the Soret maximum to 421 and 416 nm, respectively, indicating that the majority of the enzyme remained in the 6CLS state. Taken together the data revealed that the W188H mutation preferentially stabilizes the 6CLS configuration of the heme in the NOHA-alone or H4B alone state without significantly perturbing the configuration of the enzyme in other substrate- and/or cofactor-bound states.

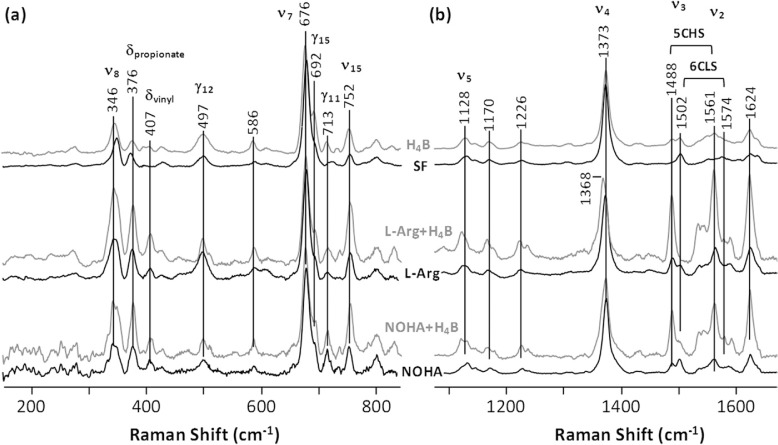

Fig. 2b shows the resonance Raman spectra of the mutant in the 1100–1700 cm−1 window. The spectrum contains vibrational modes sensitive to the oxidation state (ν4) as well as the coordination and spin state (ν3 and ν2) of the heme iron. Consistent with the optical absorption data, the SF mutant enzyme exhibited a pure 6CLS configuration, as indicated by the ν2/ν3 modes at 1574/1502 cm−1, whereas the addition of both substrate and cofactor (H4B + l l-Arg or H4B + NOHA) led to a pure 5CHS configuration, as indicated by the ν2/ν3 modes at 1561/1488 cm−1. On the other hand, the addition of either NOHA or H4B alone led to a mixed 6CLS/5CHS configuration, with the 6CLS component dominating the spectrum, whereas the l-Arg alone enzyme exhibited a mixed 6CLS/5CHS configuration but with the 5CHS component dominating the spectrum. The presence of the minor contribution of the 6CLS component that is invisible in the optical absorption spectrum (Fig. 1b) was possibly a result of the fact that, with 413.1-nm laser excitation, the Raman lines associated with the 6CLS species were more resonantly enhanced with respect to those of the 5CHS species. Nonetheless, it is evident that the addition of H4B to the l-Arg or NOHA-alone enzyme enhanced the 5CHS component.

FIGURE 2.

Resonance Raman spectra of the ferric derivatives of the W188H mutant of iNOSoxy in the low frequency (a) and high frequency window (b). The laser excitation was 413.1 nm.

Fig. 2a shows the resonance Raman spectra of the W188H mutant in the 200–800 cm−1 window. In contrast to the high frequency spectra, the low frequency spectra are sensitive to the structure of the porphyrin macrocycle. Previous studies reported by Li et al. (26) demonstrate that the heme prosthetic group in the wild type enzyme exhibits an unusually high degree of out-of-plane deformation that is sensitive to substrate and cofactor binding. Likewise, the current studies revealed that substrate and/or cofactor binding to the mutant significantly perturbed the out-of-plane distortion of the heme and the peripheral groups attached to it (including the propionate and vinyl groups). It also led to the enhancement of several modes, including the out-of-plane modes, γ15 (692 cm−1) and γ11 (713 cm−1), the pyrrole breathing mode, ν15 (752 cm−1) (27, 28), the ν8 mode (346 cm−1), the propionate bending mode (376 cm−1), and the vinyl bending mode (407 cm−1) as well as the perturbation to the line shapes and positions of the γ12 (∼497 cm−1), ν5 (1128 cm−1), and the methylene twist modes (1226 cm−1).

The Fe-S Bond Strength—In cytochrome P450s, the thiolate ligand of the heme accepts a H-bond from a peptide amide, whereas the analogous thiolate ligand in NOSs accepts a H-bond from the sidechain group of a Trp residue (Trp-188 in iNOS). The unique H-bond between the thiolate and Trp in NOSs leads to a weaker Fe-S bond that is believed to be critical for tuning the chemical reactivity of the enzymes, such that NO synthesis can be efficiently catalyzed by the various isoforms for diverse physiological demands.

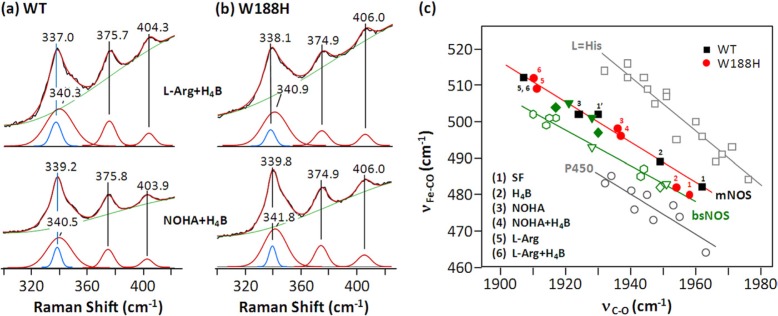

To determine how the W188H mutation affects the H-bond thereby modulating the Fe-S bond strength, we measured the frequency of the Fe-S stretching mode (νFe-S) of the mutant with respect to the wild type enzyme. As the νFe-S mode is only observable in the 5CHS ferric state (29), we examined the l-Arg ± H4B- and NOHA + H4B-bound mutant versus the wild type enzyme with excitation at 363.8 nm. As shown in Fig. 3, a and b, in the l-Arg + H4B-bound wild type enzyme, the νFe-S mode was detected at 337.0 cm−1, consistent with that reported previously (30). The same νFe-S frequency was observed with l-Arg alone (data not shown). The νFe-S frequency of NOHA + H4B-bound enzyme was slightly up-shifted to 339.2 cm−1. The W188H mutation led to ∼1-cm−1 higher frequencies for the analogous l-Arg + H4B and NOHA + H4B derivatives (338.1 and 339.8 cm−1, respectively), indicating a weaker H-bond between the residue 188 and the thiolate ligand.

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of the proximal Fe-S bond strength in the W188H mutant and wild type iNOSoxy based on the νFe-S modes (a and b) or the νFe-CO versus νC-O correlation lines (c). The frequencies of the νFe-S modes in a and b were identified by a peak-fitting software, IGOR. The raw data and base line are shown in black and green, respectively. The best-fit heme peaks and the νFe-S modes are shown in red and blue, respectively. All data points in c other than those of the W188H mutant of iNOSoxy were taken from Ref. 1. The L = His and P450 lines were defined by the data from globins and P450s, respectively. The mNOS and B. subtilis NOS (bsNOS) lines were defined by the data from mammalian NOSs (1) and B. subtilis NOS (30), respectively. The black squares and red circles are the data taken from the wild type (1, 26) and W188H mutant of iNOSoxy, respectively. For the measurements in (a and b), the concentrations of the enzyme, substrate, and cofactor were 50 μm, 5 mm, and 1 mm, respectively. The buffer was 40 mm EPPS (pH 7.6) containing 100 μm DTT. The laser excitation was 363.8 nm.

The observed νFe-S frequencies of iNOSoxy are significantly lower than those of P450s, which are ∼351 cm−1 (31), in good agreement with the presence of a strong H-bond between residue 188 and the thiolate ligand of the heme. In the crystal structure of the W188H mutant (PDB code 3DWJ), the side chain of His-188, similar to Trp-188 in the wild type enzyme, forms a H-bond with the thiolate ligand. Although the H-bond distance is similar to that in the wild type enzyme, Tejero et al. (18) proposed that the H-bond between His-188 and the thiolate ligand in the mutant is stronger, as the redox potential of the mutant is 88 mV higher than that of the wild type enzyme. In contrast to this hypothesis, our data show that the νFe-S frequencies of the W188H mutant were ∼1 cm−1 higher for the mutant as compared with the wild type enzyme, indicating only a slightly weaker H-bond in the mutant. The absence of a large frequency difference in the νFe-S modes of the mutant versus wild type enzymes is consistent with the preservation of the H-bond between residue 188 and the thiolate ligand of the heme with a strength similar to that in the WT enzymes.

CO-related Vibrational Modes—In addition to direct measurement of the νFe-S frequency, the proximal Fe-S bond strength could be estimated by the offset of the νFe-CO-νCO inverse correlation line shown in Fig. 3c. CO has been demonstrated to be an informative structural probe for the distal ligand environment in hemeproteins, as the electron density distribution on the Fe-C-O moiety is sensitive to the electrostatic potential of the protein environment surrounding the heme iron bound CO due to the π back-bonding effect (32). When the electrostatic potential is positive, the νFe-CO-νCO data points fall on the left side of the correlation line; in contrast, when the positive electrostatic potential is reduced, the νFe-CO-νCO data points fall on the right side of the correlation line (see Refs. 20 and 32 for a complete discussion). The electron density distribution on the Fe-C-O moiety is also sensitive to the electronic properties of the proximal heme ligand. Accordingly, the νC-O-νFe-CO correlation line of hemeproteins with histidine as the proximal ligand (such as globins, see the L = His line in Fig. 3c) lies higher than that of hemeproteins with cysteine as the proximal ligand (such as P450s) (32).

It has been shown that the mammalian NOSs (mNOS) correlation line is up-shifted from the P450 line due to its weaker Fe-S bond, as indicated by their lower νFe-S frequencies (∼340 versus 350 cm−1). Intriguingly, the data of some bacterial NOSs, such as those from Bacillus subtilis (30, 33), lie on a separate line (designated as the bsNOS line in Fig. 3c) in between the mNOS and P450 lines, suggesting that the Fe-S bond strength is stronger in these bacterial NOSs as compared with mNOSs.

The CO-associated modes of the W188H mutant were determined by resonance Raman spectroscopy (data not shown) and are listed in Table 1. The assignments of all the modes were confirmed by CO isotopic substitution experiments. As shown in Fig. 3c, the νC-O/νFe-CO data points of both the wild type and W188H mutant of iNOSoxy (indicated by black squares and red circles, respectively) are sensitive to the substrate and/or cofactor bound to the active site. In the SF wild type enzyme, two Fe-CO conformers were identified, with the major and minor population labeled as point #1 and 1∼, respectively. H4B binding to the enzyme led to the merging of the two data points into one lying between them (point #2). l-Arg binding, on the other hand, shifted the data points along the correlation line to the upper left corner (Fig. 3c, points 5 and 6) irrespective of H4B binding. NOHA binding led to the shift of the data point to a location (point 3) close to the minor conformer of the substrate-free enzyme. On the other hand, in the SF W188H mutant, two conformers labeled as points 1 and 2 were identified on the B. subtilis NOS line irrespective of H4B. The data indicate that the mutation led to a stronger Fe-S bond in the SF mutant with respect to the wild type enzyme. Surprisingly, l-Arg or NOHA binding caused the shift of the data points back to the mNOS line (as indicated by points 5 and 6 and points 3 and 4, respectively), indicating that substrate binding in the distal heme pocket of the mutant weakens the proximal Fe-S bond strength as compared with the SF enzyme.

TABLE 1.

The CO-dependent vibrational modes of the W188H mutant of iNOSoxy in various substrate and cofactor bound states

| W188H mutant | νFe-CO | νC-O | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| 12C16O | 13C18O | 12C16O | 13C18O | |

| cm−1 | cm−1 | |||

| Substrate-free | 480 | 468 | 1958 | 1859 |

| 500shoulder | 490shoulder | |||

| H4B only | 482 | 470 | 1954 | 1865 |

| 505shoulder | 500shoulder | |||

| Arg only | 509sharp | 497sharp | 1911 | 1828 |

| Arg + H4B | 512sharp | 498sharp | 1910 | 1833 |

| NOHA | 498 | 480 | 1936 | 1830 |

| NOHA + H4B | 496 | 484 | 1937 | 1830 |

It is noteworthy that similar studies of the W56H mutant of a bacterial NOS from Staphylococcus aureus, analogous to the W188H mutant of iNOSoxy, were reported recently (34). However, it was found that the W56H mutation only slightly perturbed the νFe-CO and νC-O frequencies in all substrate-and/or cofactor-bound states examined, indicating the structural properties of S. aureus NOS are distinct from those of mNOS.

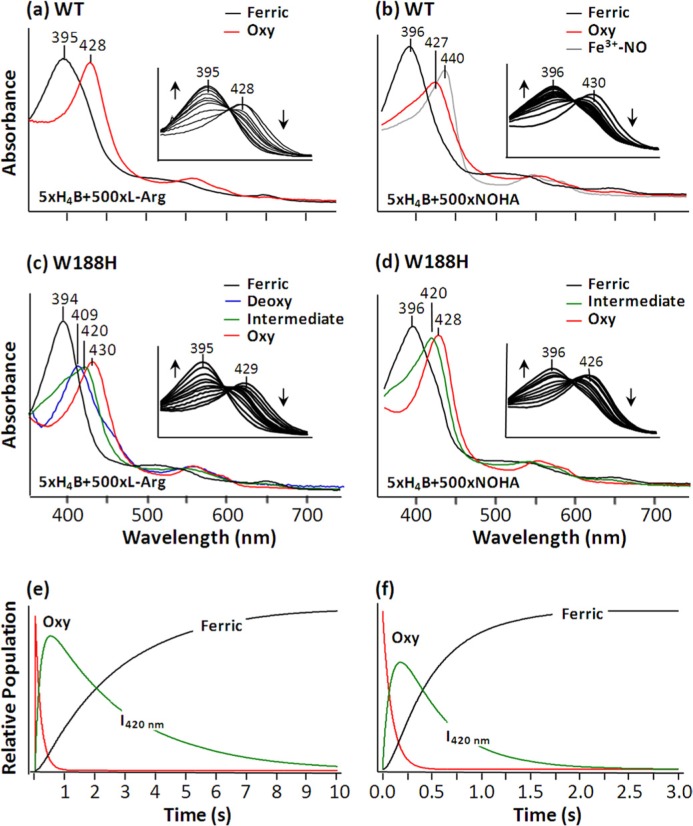

The 420-nm Intermediate—To understand how the W188H mutation modulates the oxygen chemistry catalyzed by iNOSoxy, the l-Arg and NOHA reactions of the W188H mutant were carried out in the presence of H4B under single turnover conditions. Comparable reactions of the wild type enzyme were examined as a reference. As shown in the inset in Fig. 4a, the l-Arg reaction of the wild type enzyme resulted in rapid formation of the O2 complex, with a Soret maximum at 428 nm. The O2 complex subsequently converted to the ferric 5CHS species with a Soret maximum at 395 nm at a rate of 13 s−1 without populating any intermediates (Equation 1), as indicated by the presence of a clear isosbestic point.

| (Eq. 1) |

The l-Arg reaction carried out by the W188H mutant also led to the rapid production of the O2 complex, with a Soret maximum at 430 nm, which subsequently converted to the ferric 5CHS species with a Soret maximum at 394 nm (see the inset in Fig. 4c). However, no isosbestic point was observed during the conversion, indicating the presence of an additional intermediate, as described in Equation 2. Global analysis revealed that the intermediate had a Soret maximum at 420 nm, with a small shoulder at ∼390 nm.

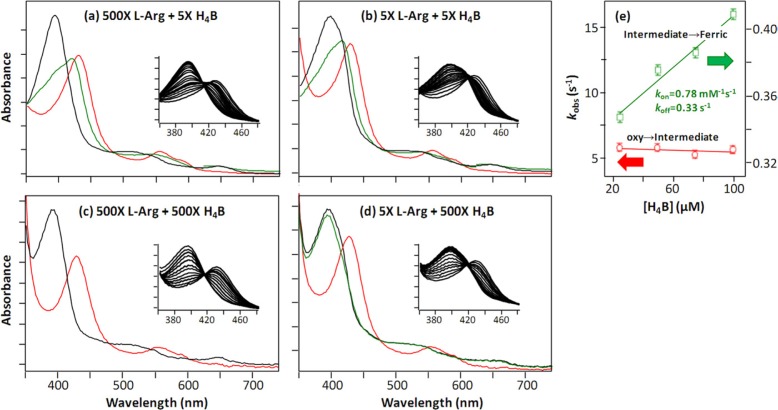

FIGURE 4.

Single turnover of thel-Arg reaction (c and e) and NOHA reaction (d and f) of the W188H mutant of iNOSoxy compared with the corresponding reactions of the wild type enzymes (a and b). The insets in a– d show the expanded view of the Soret band as a function of time. The pure spectra of the species populated during the reactions obtained by global analysis of the time-dependent data are shown in a– d; the associated kinetic traces associated with c and d are shown in e and f, respectively. The reactions were carried out with 10 μm enzyme, 5 mm substrate, and 50 μm H4B at 20 °C.

| (Eq. 2) |

The I420 nm intermediate was maximally populated at ∼500 ms and subsequently decayed to the ferric species at a rate of 0.33 s−1 (Fig. 4e), similar to the previously reported data (18). The same experiment carried out in the absence of DTT (the reductant used to prevent H4B oxidation) showed similar results, indicating that the presence of small amount of DTT did not interfere with the reaction kinetics.

In the NOHA reaction of the wild type enzyme, a similar O2 binding and oxidation process was observed (Fig. 4b). Global analysis revealed transient population of the NO-bound ferric species with a Soret maximum at 440 nm due to the binding of the product NO to the ferric heme. The NO-bound ferric species ultimately converted to the 5CHS ferric species with a Soret maximum at 396 nm by releasing NO, as described in Equation 3.

| (Eq. 3) |

In the NOHA reaction of the W188H mutant, the O2 complex with a Soret maximum at 428 nm was observed within the dead time of the instrument, which ultimately converted to the ferric 5CHS species with a Soret maximum at 396 nm (Fig. 4d). Surprisingly, global analysis revealed that the NO-bound ferric intermediate observed in the wild type reaction was not populated in the mutant reaction. Instead, a transient intermediate with a Soret maximum at 420 nm, similar to that observed in the l-Arg reaction, was maximally populated at ∼185 ms and decayed to the ferric species at a rate of 0.17 s−1 (Fig. 4f), as described in Equation 4.

| (Eq. 4) |

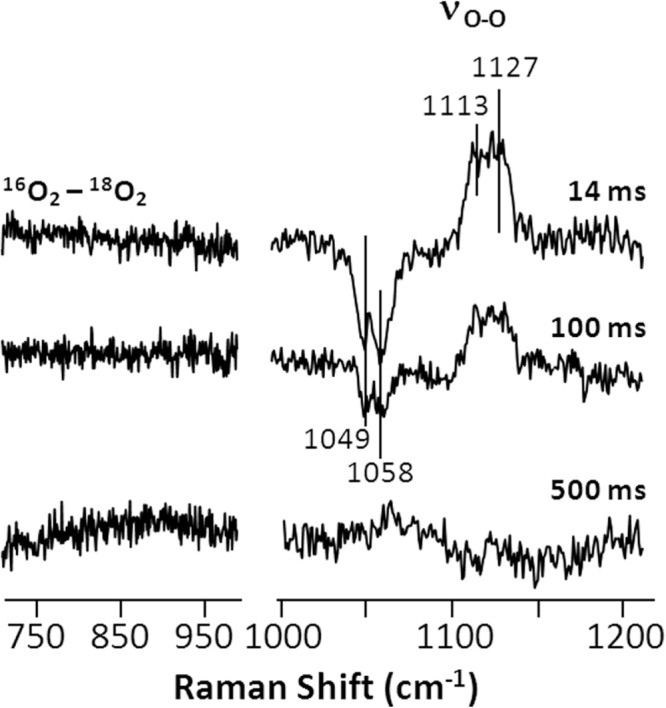

The Identity of the 420-nm Intermediate—To examine if I420 nm is an oxygen containing intermediate, we carried out continuous-flow resonance Raman measurements of the intermediate populated during the l-Arg reaction. On the basis of the kinetic profile shown in Fig. 4e, 3 time points, 14, 100, and 500 ms (corresponding to a population of 0, 50, and 100% intermediate, respectively), were examined. To identify oxygen-containing vibrational modes, the 16O2-18O2 isotope difference spectra were calculated. As shown in Fig. 5, only two O-O stretching modes (νO-O) centered at ∼1113 and 1127 cm−1, similar to that reported for the O2-complex of the wild type enzyme (35), were identified.

FIGURE 5.

Time-resolved 16O2-18O2 isotope difference spectra obtained during the l-Arg reaction of the W188H mutant of iNOSoxy. The reactions were carried out with 40 μm enzyme, 400 μm l-Arg, and 200 μm H4B. The laser excitation was 413.1 nm.

On the basis of the previously proposed mechanism (1), other than the primary O2-complex, two potential oxygen-containing intermediates, a ferric peroxo species (Fe3+ - ) and a Cmpd I type of ferryl species (Fe4+ = O2−) might be populated during the l-Arg and NOHA reactions. Our data showed that at all three time points, no signal was detected in the ∼700–950-cm−1 region of the 16O2-18O2 difference spectra, where the characteristic oxygen-related modes of typical peroxo and ferryl species are located. It is important to note that although our data show no evidence supporting the assignment of I420 nm to either the peroxo or ferryl species, we could not rule out the possibility that these modes were too weak to be detected with the 413.1-nm excitation.

The Soret maximum of the peroxo derivatives of Geobacillus stearothermophilus NOS (9) and P450 (36) have been identified at ∼440 nm by cryoreduction methods. It is inconsistent with the Soret maximum of I420 nm, ruling out the assignment of I420 nm to a peroxo species. To examine if I420 nm is associated with any minute peroxo species, which was too weak to be detected by absorption measurements, we repeated the continuous flow resonance Raman measurements with 441.6-nm excitation (to resonantly enhance the modes associated with the potential peroxo species). Again, we observed no evidence for peroxo species, indicating that the peroxo species is not populated during the mutant reaction.

The absorption spectrum of the Cmpd I ferryl derivative of NOS has not been reported. We sought to generate the Cmpd I derivative of iNOSoxy by reacting the ferric enzyme with m-chloroperbenzoic acid, which had been widely used to generate ferryl derivatives of hemeproteins (37, 38). We found that immediately after the initiation of the reaction, a species with a Soret maximum at 421 nm, which we assign to the m-chloroperbenzoic acid-bound ferric species, was observed (data not shown). It gradually converted to an intermediate with a Soret maximum at 409 nm with a shoulder at 350 nm within 2.0 s. The 409-nm intermediate was assigned to the Cmpd I intermediate of iNOSoxy derived from the heterolytic O-O bond cleavage reaction of the m-chloroperbenzoic acid-bound ferric species. The spectral properties of the Cmpd I derivative of iNOSoxy are consistent with that of the Cmpd I derivative of P450 identified in the m-chloroperbenzoic acid reaction with the ferric enzyme (37) and in the photo-oxidation reaction of a Cmpd II intermediate (39). It is also similar to the Cmpd I derivative of chloroperoxidase derived from the H2O2 reaction (40). These data support the scenario that I420 nm is not a Cmpd I type of ferryl species.

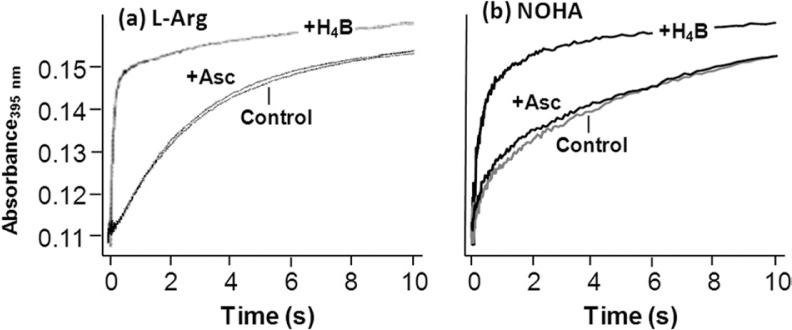

To further confirm that I420 nm is not a ferryl species, we examined its lifetime in the presence and absence of ascorbate, which is a good reductant for Cmpd I or Cmpd II types of ferryl species (41), by carrying out sequential mixing experiments in a stopped-flow system. In these experiments the substrate- and cofactor-bound ferrous mutant was first mixed with O2-containing buffer in the first mixer. The reaction mixture was allowed to age until I420 nm was maximally populated before it was mixed with a buffer in the presence or absence of ascorbate in the second mixer. The population of I420 nm was then followed as a function of time by monitoring the absorption increase at 395 nm. The data show that the presence of ascorbate did not affect the decay rate of I420 nm (Fig. 6). Comparable experiments carried out with ferrocyanide (instead of ascorbate), which is also a potential reductant for ferryl species, showed similar results (data not shown), confirming that I420 nm is not a ferryl species.

FIGURE 6.

Effect of ascorbate and H4B on the lifetime of the 420-nm intermediate populated during the l-Arg (a) and NOHA (b) reaction of the W188H mutant of iNOSoxy. The data shown in a and b were obtained from sequential mixing experiments in which the substrate and cofactor bound ferrous enzyme was first mixed with O2-containing buffer, aged until the maximum population of the intermediate was reached, and then mixed again with ascorbate or H4B-containing buffer or buffer alone (as a control) before the data acquisition. The concentrations of ascorbate and H4B were 20 and 5 mm, respectively.

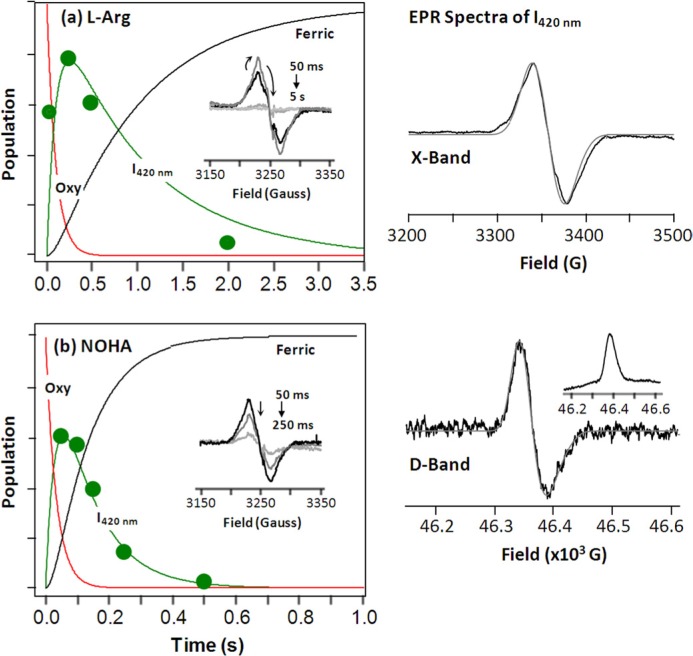

The 420-nm Intermediate Is Associated with an H4B+· Radical—It has been proposed that during the NOS reaction, the H4B cofactor acts as an electron donor to the heme, yielding a one electron oxidized cation radical (H4B+·) that is subsequently re-reduced to the neutral species (42–46). The EPR spectra of the H4B+· derived from the wild type iNOSoxy has been reported by Stoll et al. (47). To examine if I420 nm was associated with any radical species, such as H4B+·, we used a home-built rapid freeze-quenching apparatus (22) to trap I420 nm derived from the l-Arg reaction and characterized it with both conventional X-band (9.4 GHz) and high-field D-band (130 GHz) EPR spectroscopy.

Our data (Fig. 7, right panels) confirmed that I420 nm populated during the l-Arg reaction is indeed associated with a radical as reported by Tejero et al. (18). The X-band spectrum exhibited hyperfine structure that is consistent with the well characterized biopterin radical (42, 44, 47–49). The D-band spectrum could be simulated with g1 = 2.0043, g2 = 2.0031, and g3 = 2.0021 by using the H4B+· parameters determined in the wild type reaction (47) as a starting point. The X-band spectrum could be nicely fitted with these g values determined by the D-band data, confirming the assignment of the radical to H4B+·.

FIGURE 7.

Time evolution of the radical species associated with the 420-nm intermediate populated during the l-Arg reaction (a) and NOHA reaction (b) of the W188H mutant of iNOSoxy. The green circles indicate the radical population determined by X-band EPR. The raw time-resolved X-band EPR spectra are shown in the insets; the associated arrows indicate the spectral change as a function of time. The solid red, green, and black traces are the kinetic traces associated with the oxy species, the 420-nm, intermediate, and the ferric product, respectively, derived from global analysis of the stopped-flow data. The right panels show the characteristic X-band and D-band EPR spectra of the 420-nm intermediate derived from the l-Arg reaction. The raw spin echo-pulsed D-band spectrum, acquired as an absorption spectrum, is shown in the inset. The best simulated absorption spectrum is plotted against the derivative of the smoothed D-band data. The best simulated X-band and D-band data are shown in gray. The X-band and D-band EPR spectra were obtained at 50 and 7 K, respectively. The reactions associated with the stopped-flow data were carried out with 100 μm enzyme, 7 mm substrate, and 0.5 mm H4B at 28 °C. The reactions associated with the EPR data were carried out with 150 μm enzyme, 10 mm substrate, and 750 μm H4B at 28 °C. It is noted that the differences in the stopped-flow kinetic traces of the intermediate shown here as compared with those shown in Fig. 4 are a result of the difference in the temperature of the measurements.

It is important to note that the g values we determined differ slightly from those reported by Stoll et al. (47) for the wild type enzyme, in which the g2 value was 2.00353. It is unclear if the small difference in the g value reflects the structural difference in the H4B+· radical itself or in the environment surrounding the radical. Nevertheless, our data demonstrated that the EPR spectra of I420 nm could be accounted for by a single set of g values associated with H4B+·, indicating that only a single radical is associated with the intermediate. In accord with the conclusions drawn from our optical absorption and resonance Raman data, the EPR data exclude the possibility that I420 nm is a Cmpd I ferryl species, as the EPR spectra of the π-cation radical associated with a Cmpd I ferryl are typically highly anisotropic and broad with rhombic symmetry (50, 51). Time-dependent EPR measurements along with comparable stopped-flow experiments demonstrate that the H4B+· radical is kinetically coupled to I420 nm during both steps of the mutant reaction (Fig. 7, a and b), confirming that the radical is specifically associated with the intermediate.

It has been shown that during the l-Arg reaction of the wild type iNOSoxy domain, the re-reduction of the H4B+· radical to the neutral species occurs slowly via random processes because of the lack of the reductase domain; hence, the radical can be significantly populated and is readily detectable (42–46). In contrast, the H4B+· radical associated with the NOHA reaction cannot be populated to an appreciable level, because it can be rapidly re-reduced by the immediate product of the reaction, HNO or NO− (leading to the generation of the final product NO•); consequently, the radical decays at least 10 times faster than that observed during the l-Arg reaction (42, 44, 46). The surprisingly high level of the H4B+· radical observed during the NOHA reaction of the W188H mutant (Fig. 7b) suggests that either the structural perturbation introduced by the mutation retarded electron transfer from HNO/NO− to H4B+· or the enzyme is incapable of producing HNO/NO−. The latter scenario is excluded as the enzyme has been shown to be active in producing NO during multiple-turnover conditions (18).

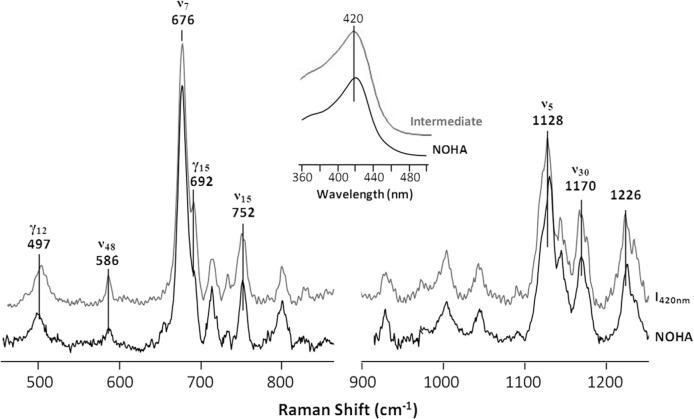

The 420-nm Intermediate Is Associated with a Hydroxide-bound Heme—The aforementioned spectroscopic data demonstrated that I420 nm is not a peroxo or ferryl species, and it has a H4B+· radical associated with it. To further investigate its identity, we surveyed the absorption spectra of all potential derivatives of the enzyme and found that the NOHA-bound 6CLS ferric species has an optical absorption spectrum similar to it (inset in Fig. 8). In addition, the resonance Raman spectrum of the NOHA-bound 6CLS ferric species strikingly resembled that of I420 nm (Fig. 8). Accordingly, we propose that I420 nm is a 6CLS species in which the heme iron is coordinated by a hydroxide ligand with an H4B+· radical occupying the cofactor-binding site. A hydroxide ligand instead of a water ligand is proposed on the following basis. (a) Our earlier studies (1) suggested the same intermediate for the NOHA reaction, although the intermediate has never been experimentally observed (b) Structural data suggest that an unique out-of-plane distortion of the heme was introduced by the W188H mutation, which specifically stabilized the hydroxide ligand (see below). (c) The negatively charged hydroxide ligand plausibly can be stabilized by the H4B+· cation radical associated with the intermediate.

FIGURE 8.

Comparison of the spectroscopic properties of the 420-nm intermediate of the W188H mutant of iNOSoxy with those of the NOHA-bound 6CLS ferric derivative of the enzyme. The resonance Raman spectra the NOHA-bound enzyme are taken from Fig. 2. The optical absorption spectra shown in the inset are taken from Figs. 1b and 4c.

Intriguingly, we observed that high concentrations of H4B significantly shortened the lifetime of I420 nm (Fig. 6), indicating that H4B destabilized the intermediate. This observation prompted us to hypothesize that the excess of H4B reduces or replaces the H4B+· radical bound to the intermediate, thereby promoting its decay back to the resting ferric state. To test this hypothesis, we carried out stopped-flow measurements of the l-Arg reaction under four different conditions, with l-Arg and H4B systematically varied. As shown in Fig. 9, a versus c, the increase of H4B from 5× to 500× of the enzyme concentration led to the disappearance of I420 nm. Similar H4B dependence was observed independent of l-Arg (Fig. 9, b versus d), although when l-Arg was low, global analysis revealed a new ferric intermediate (ferric′) with a Soret maximum at 395 nm (Fig. 9d), as described in Equation 5.

| (Eq. 5) |

It is noted that the weak shoulder at ∼420 nm in the spectrum of the ferric′ intermediate was attributed to a minor population of I420 nm unresolved by the deconvolution process.

FIGURE 9.

Single turnover reaction of the W188H mutant of iNOSoxy as a function of [l-Arg] and H4B. In a– d, the spectra of the oxy (red), intermediate (green), and final ferric product (black) identified from global analysis of the time-dependent data are displayed. The inset in each panel shows the expanded view of the Soret band as a function of time. The spectrum of the deoxy species is omitted in each panel for clarity. The intermediates in a and b are the 420-nm species, whereas that in d is the ferric′ species (see text, Eq. 5). In e, the decay rate of the oxy to intermediate and that from the intermediate to the final ferric product obtained from the l-Arg (500×) reaction of W188H are plotted as a function of H4B. The enzyme concentration was 10 μm.

Comparable H4B-dependent studies of the NOHA reaction showed that, like the l-Arg reaction, I420 nm was detected only when the H4B concentration was low regardless of the NOHA concentration (data not shown). However, when the NOHA concentration was low, the ferric′ intermediate was not detected; instead, the reaction followed a two-step mechanism,

| (Eq. 6) |

Systematic H4B-dependent studies of the l-Arg reaction (Fig. 9e) showed that the formation rate of the intermediate from the oxygen complex remained constant, ∼5 s−1, whereas its decay rate to the resting ferric state increased linearly with increasing H4B concentration. A linear fit of the data yielded kon = 0.78 mm−1 s−1 and koff = 0.33 s−1, based on the slope and intercept of the best fitted line. The data confirm that the excess of H4B reduces or replaces the H4B+· radical associated with I420 nm, thereby facilitating its conversion to the resting ferric state.

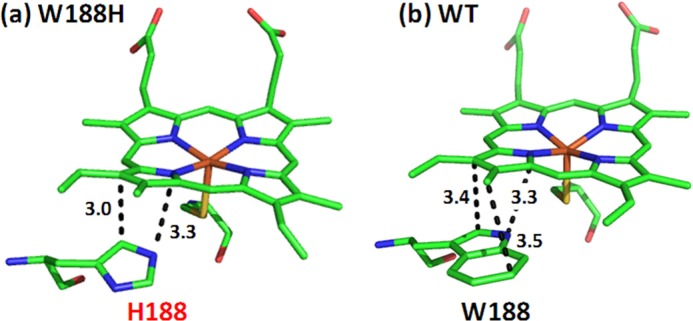

The Structural Change Introduced by the W188H Mutation—How does the proximal W188H mutation stabilize the distal hydroxide ligand and the H4B+· associated with it during the NOS reaction? The structure of the W188H mutant has been resolved in the H4B bound state (without any substrate), whereas that of the wild type enzyme has been determined in various substrate and cofactor-bound states. In the H4B-bound wild type enzyme, Trp-188 donates a H-bond to the thiolate ligand of the heme via its side chain; in addition, its indole ring forms a π-stacking interaction with the porphyrin macrocycle (Fig. 10b). In the H4B-bound mutant enzyme, the side chain of His-188 also forms a H-bond with the thiolate ligand; however, its imidazole ring is rotated out of the parallel position with respect to the porphyrin (Fig. 10a), which creates a steric clash with a pyrrole ring of the porphyrin, thereby introducing a unique out-of-plane twist to it.

FIGURE 10.

Structural comparison of the H4B-bound derivatives of the W188H mutant (a) and wild type (b) iNOSoxy. The PDB codes are 3DWJ and 2NOD, respectively. H4B was not shown for clarity.

The nonplanar deformation of the heme in the wild type iNOSoxy as well as its critical role in controlling the catalytic and NO autoinhibition properties of the enzyme, have been reported previously by Li et al. (1). To quantify how the W188H mutation affects the out-of-plane distortion of the heme, we employed the Normal Coordinate Structural Decomposition (NSD) analysis method (52) to evaluate the structure of the heme in the W188H mutant versus the wild type enzyme (PDB code 3DWJ and 2NOD, respectively). The data show that the mutation significantly enhances the out-of-plane distortion of the heme, with a composite out-of-plane displacement of 1.18 and 0.77 Å for the mutant and the wild type enzyme, respectively (Table 2). We found that in the mutant the largest enhancement was along the B1u (ruffling) symmetry (0.88 Å), whereas that in the wild type enzyme was along the B2u (saddling) symmetry (0.58 Å).

TABLE 2.

Normal-coordinate structural decomposition analysis (52) of the heme in the subunit A of the H4B-bound W188H mutant and wild type of iNOSoxy (PDB codes 3DWJ and 2NOD, respectively)

The distortion of the heme was decomposed to six symmetry types. Dip and dip columns show the composite in-plane distortions and the mean deviations, respectively; Doop and doop columns show the composite out-of-plane distortions and mean deviations, respectively.

| W188H | Dip | dip | B2g | B1g | Eu(x) | Eu(y) | A1g | A2g |

| 0.3035 | 0.0000 | 0.0617 | 0.1901 | 0.1233 | 0.1202 | 0.1421 | 0.0480 | |

| Doop | doop | B2u | B1u | A2u | Eg(x) | Eg(y) | A1u | |

| 1.1748 | 0.0000 | 0.6507 | 0.8484 | 0.3598 | 0.1367 | 0.2971 | 0.0223 | |

| WT | Dip | dip | B2g | B1g | Eu(x) | Eu(y) | A1g | A2g |

| 0.2886 | 0.0000 | 0.0671 | 0.0566 | 0.0720 | 0.1139 | 0.2372 | 0.0334 | |

| Doop | doop | B2u | B1u | A2u | Eg(x) | Eg(y) | A1u | |

| 0.7655 | 0.0000 | 0.5790 | 0.4195 | 0.2628 | 0.0303 | 0.0690 | 0.0047 |

It has been shown that in H-NOX (a heme nitric oxide/oxygen-binding protein), heme distortion significantly reduces the electron density at the heme iron, which leads to an increase in the redox potential of the heme and a decrease in the pKa of the distal water bound to it (53). We hypothesize that the enhanced heme distortion in the W188H mutant also reduces the electron density at the heme iron (evident by the 88-mV higher redox potential (18)), thereby stabilizing the hydroxide ligand in I420 nm. The unique heme distortion introduced by the mutation might further stabilize I420 nm by perturbing the interactions between the heme, substrate (l-Arg or NOHA), and cofactor (H4B), which are linked together via an extended H-bonding network mediated by a propionate group of the heme.

DISCUSSION

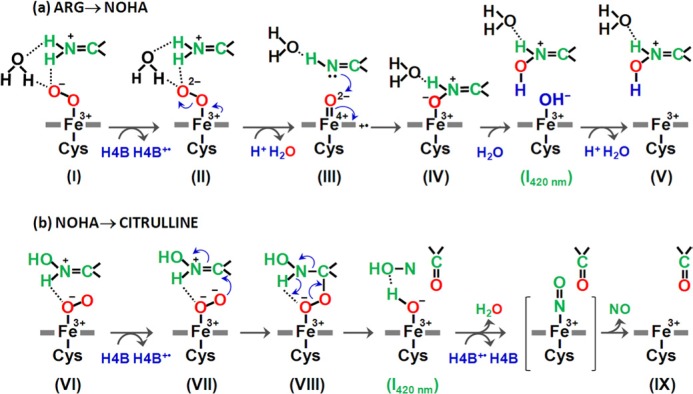

Our previous studies suggest that the NOHA reaction catalyzed by NOS goes through a hydroxide-bound ferric heme intermediate, with H4B+· associated with it (1), but it is too short-lived to be experimentally observed. In this work we demonstrated that this intermediate is stabilized by the W188H mutation and that the intermediate exhibits a Soret maximum at 420 nm. We showed that the intermediate is populated not only during the NOHA reaction but also during the l-Arg reaction. On the basis of this new finding, we postulate a modified catalytic mechanism as illustrated in Fig. 11.

FIGURE 11.

The two-step mechanism of NOS. The mechanism was modified from that reported by Li et al. (1). The NO-bound inhibitory complex observed in the second step of the wild type enzyme, but unresolved in the W188H mutant, is shown in the bracket in b.

In the first step of the reaction, the ferric 5CHS heme is reduced to the ferrous form by accepting an electron from the reductase domain. It is followed by O2 binding to generate the O2-complex (I), with a ferric superoxide electronic configuration. The ferric superoxide species is reduced to a ferric peroxy species (II) by accepting an electron from H4B, leaving a cation radical on H4B. The ferric peroxo species, with the terminal oxygen forming H-bonds with l-Arg and a water molecule next to it (1, 54), accepts a proton, which triggers the heterolytic O-O bond cleavage, leading to a Cmpd I type of ferryl species, with a π-cation radical on the porphyrin ring (III). At the same time, a water molecule is released from the active site. The ferryl oxygen of the Cmpd-I species is then inserted into l-Arg to generate a postulated O-bound product heme complex (IV). The O-bound product accepts a proton from a water molecule, which triggers its dissociation from the heme iron. Concurrently, the hydroxide from the water molecule binds to the ferric heme to generate the I420 nm species. The subsequent one-electron reduction of H4B+· back to the neutral species (by the reductase domain in the full-length enzyme or by random processes in the oxygenase domain) promotes the uptake of a proton to the active site to maintain its charge neutrality (55) and converts the hydroxide ligand to water. The water subsequently dissociates from the heme iron, thereby regenerating the resting 5CHS species (V), with NOHA bound to it. It should be noted that the current data could not exclude the possibility that H4B+· decays via oxidation to H2B + 2H+ (44). In the wild type reaction, H4B+· was transiently populated after the decay of the O2 complex (I), but no heme intermediate was detected as the reaction was rate-limited by the electron transfer from H4B to the O2 complex (1).

In the second step of the reaction the ferric 5CHS heme is reduced to its ferrous state by accepting an electron from the reductase domain. The ferrous enzyme then binds O2 to form the ferric superoxide species (VI). The ferric superoxide species accepts an electron from H4B to produce the ferric peroxo species (VII) with H4B+· associated with it. The proximal oxygen atom of the heme iron-bound peroxide forms a H-bond with the substrate, NOHA, which induces the addition of the terminal oxygen to the substrate, leading to the ferric iron-bound alkyl peroxo species (VIII). The subsequent bond rearrangement produces HNO and citrulline as well as the hydroxide-bound ferric heme intermediate, I420 nm. HNO is oxidized to NO by transferring an electron to H4B+· to regenerate its neutral form; at the same time the proton converts the hydroxide ligand to water, which subsequently dissociates from the iron to regenerate the resting 5CHS ferric heme species (IX).

In the wild type reaction, the product, NO, binds to the ferric heme iron, generating a transient NO-bound ferric intermediate (shown in brackets) before it diffuses out of the active site into free solution. This NO-bound ferric intermediate, surprisingly, was not observed in the mutant reaction. On the contrary, I420 nm observed in the mutant reaction was not observed in the wild type reaction. These data indicate that the structural changes to the enzyme introduced by the W188H mutation stabilize the hydroxide ligand bound to the ferric heme iron and the H4B+· associated with it; at the same time they prevent transient binding of NO to the heme iron before it escapes out of the enzyme. The fact that the increase in H4B facilitates the decay of I420 nm to the resting 5CHS ferric species (Fig. 9e) suggests that H4B+· can be reduced not only by HNO but also by the excess H4B in free solution. The observation that I420 nm is kinetically coupled to the formation and decay of H4B+· demonstrates that the protonation of hydroxide to water and its subsequent dissociation was triggered by the reduction of H4B+· bound in the vicinity of the heme; in other words the negatively charged hydroxide ligand in I420 nm is stabilized by the cation radical located on H4B.

Acknowledgments

We thank Vladimir Krymov for technical assistance with the EPR measurements.

Footnotes

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM54806 (to D. L. R.), F31GM078679 (to J. S.), and CA53914, GM51491, and HL76491 (to D. J. S.). This work was also supported by National Science Foundation Grants NSF1026788 (to D. L. R.) and NSF0956358 (to S.-R. Y.).

The abbreviations used are: NOHA, N-hydroxy-l-arginine; Cmpd I, compound I; iNOS, inducible NOS; iNOSoxy, the oxygenase domain of iNOS; H4B, tetrahydrobiopterin; EPPS, N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-3-propane-sulfonic acid; 6CLS, six-coordinate low spin; 5CHS, five-coordinate high spin; SF, substrate and cofactor-free; mNOS, mammalian NOS.

REFERENCES

- 1.Li D, Kabir M, Stuehr DJ, Rousseau DL, Yeh SR. Substrate- and isoform-specific dioxygen complexes of nitric-oxide synthase. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:6943–6951. doi: 10.1021/ja070683j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alderton WK, Cooper CE, Knowles RG. Nitric-oxide synthases. Structure, function, and inhibition. Biochem J. 2001;357:593–615. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cho KB, Carvajal MA, Shaik S. First half-reaction mechanism of nitric-oxide synthase. The role of proton and oxygen coupled electron transfer in the reaction by quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:336–346. doi: 10.1021/jp8073199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giroud C, Moreau M, Mattioli TA, Balland V, Boucher JL, Xu-Li Y, Stuehr DJ, Santolini J. Role of arginine guanidinium moiety in nitric-oxide synthase mechanism of oxygen activation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7233–7245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.038240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurshman AR, Marletta MA. Reactions catalyzed by the heme domain of inducible nitric-oxide synthase. Evidence for the involvement of tetrahydrobiopterin in electron transfer. Biochemistry. 2002;41:3439–3456. doi: 10.1021/bi012002h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stuehr DJ, Santolini J, Wang ZQ, Wei CC, Adak S. Update on mechanism and catalytic regulation in the NO synthases. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:36167–36170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woodward JJ, Chang MM, Martin NI, Marletta MA. The second step of the nitric-oxide synthase reaction. Evidence for ferric-peroxo as the active oxidant. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:297–305. doi: 10.1021/ja807299t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davydov R, Ledbetter-Rogers A, Martásek P, Larukhin M, Sono M, Dawson JH, Masters BS, Hoffman BM. EPR and ENDOR characterization of intermediates in the cryoreduced oxy-nitric-oxide synthase heme domain with bound l-arginine or N(G)-hydroxyarginine. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10375–10381. doi: 10.1021/bi0260637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davydov R, Sudhamsu J, Lees NS, Crane BR, Hoffman BM. EPR and ENDOR characterization of the reactive intermediates in the generation of NO by cryoreduced oxy-nitric-oxide synthase from Geobacillus stearothermophilus. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:14493–14507. doi: 10.1021/ja906133h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung C, Lendzian F, Schünemann V, Richter M, Böttger LH, Trautwein AX, Contzen J, Galander M, Ghosh DK, Barra AL. Multi-frequency EPR and Mössbauer spectroscopic studies on freeze-quenched reaction intermediates of nitric-oxide synthase. Magn Reson Chem. 2005;43:S84–S95. doi: 10.1002/mrc.1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshioka S, Takahashi S, Ishimori K, Morishima I. Roles of the axial push effect in cytochrome P450cam studied with the site-directed mutagenesis at the heme proximal site. J Inorg Biochem. 2000;81:141–151. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)00097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adak S, Crooks C, Wang Q, Crane BR, Tainer JA, Getzoff ED, Stuehr DJ. Tryptophan 409 controls the activity of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase by regulating nitric oxide feedback inhibition. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26907–26911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adak S, Stuehr DJ. A proximal tryptophan in NO synthase controls activity by a novel mechanism. J Inorg Biochem. 2001;83:301–308. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)00176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adak S, Wang Q, Stuehr DJ. Molecular basis for hyperactivity in tryptophan 409 mutants of neuronal NO synthase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17434–17439. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000846200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Couture M, Adak S, Stuehr DJ, Rousseau DL. Regulation of the properties of the heme-NO complexes in nitric-oxide synthase by hydrogen bonding to the proximal cysteine. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38280–38288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santolini J, Meade AL, Stuehr DJ. Differences in three kinetic parameters underpin the unique catalytic profiles of nitric-oxide synthases I, II, and III. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48887–48898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108666200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson DJ, Rafferty SP. A structural role for tryptophan 188 of inducible nitric-oxide synthase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;287:126–129. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tejero J, Biswas A, Wang ZQ, Page RC, Haque MM, Hemann C, Zweier JL, Misra S, Stuehr DJ. Stabilization and characterization of a heme-oxy reaction intermediate in inducible nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:33498–33507. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806122200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghosh DK, Wu C, Pitters E, Moloney M, Werner ER, Mayer B, Stuehr DJ. Characterization of the inducible nitric-oxide synthase oxygenase domain identifies a 49-amino acid segment required for subunit dimerization and tetrahydrobiopterin interaction. Biochemistry. 1997;36:10609–10619. doi: 10.1021/bi9702290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Egawa T, Yeh S. Structural and functional properties of hemoglobins from unicellular organisms as revealed by resonance Raman spectroscopy. J Inorg Biochem. 2005;99:72–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takahashi S, Yeh S-R, Das TK, Chan C-K, Gottfried DS, Rousseau DL. Folding of cytochrome c initiated by submillisecond mixing. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:44–50. doi: 10.1038/nsb0197-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin Y, Gerfen GJ, Rousseau DL, Yeh SR. Ultrafast microfluidic mixer and freeze-quenching device. Anal Chem. 2003;75:5381–5386. doi: 10.1021/ac0346205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krymov V, Gerfen GJ. Analysis of the tuning and operation of reflection resonator EPR spectrometers. J Magn Reson. 2003;162:466–478. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(03)00109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ranguelova K, Girotto S, Gerfen GJ, Yu S, Suarez J, Metlitsky L, Magliozzo RS. Radical sites in Mycobacterium tuberculosis KatG identified using electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, the three-dimensional crystal structure, and electron transfer couplings. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6255–6264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607309200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rousseau DL, Li D, Couture M, Yeh SR. Ligand-protein interactions in nitric-oxide synthase. J Inorg Biochem. 2005;99:306–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li D, Stuehr DJ, Yeh SR, Rousseau DL. Heme distortion modulated by ligand-protein interactions in inducible nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:26489–26499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Czernuszewicz RS, Li XY, Spiro TG. Nickel octaethyl-porphyrin ruffling dynamics from resonance Raman spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:7024–7031. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Czernuszewicz RS, Rankin JG, Lash TD. Fingerprinting petroporphyrin structures with vibrational spectroscopy. 4. Resonance Raman spectra of nickel(II) cycloalkanoporphyrins. Structural effects due to exocyclic ring size. Inorg Chem. 1996;35:199–209. doi: 10.1021/ic950749o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schelvis JP, Berka V, Babcock GT, Tsai AL. Resonance Raman detection of the Fe-S bond in endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:5695–5701. doi: 10.1021/bi0118456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santolini J, Roman M, Stuehr DJ, Mattioli TA. Resonance Raman study of Bacillus subtilis NO synthase-like protein. Similarities and differences with mammalian NO synthases. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1480–1489. doi: 10.1021/bi051710q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Champion PM, Stallard BR, Wagner GC, Gunsalus IC. Resonance Raman detection of an iron-sulfur bond in cytochrome P 450cam. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:5469–5472. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spiro TG, Wasbotten IH. CO as a vibrational probe of heme protein active sites. J Inorg Biochem. 2005;99:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kabir M, Sudhamsu J, Crane BR, Yeh SR, Rousseau DL. Substrate-ligand interactions in Geobacillus stearothermophilus nitric-oxide synthase. Biochemistry. 2008;47:12389–12397. doi: 10.1021/bi801491e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lang J, Santolini J, Couture M. The conserved Trp-Cys hydrogen bond dampens the “push effect” of the heme cysteinate proximal ligand during the first catalytic cycle of nitric-oxide synthase. Biochemistry. 2011;50:10069–10081. doi: 10.1021/bi200965e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baka E, Comer JE, Takács-Novák K. Study of equilibrium solubility measurement by saturation shake-flask method using hydrochlorothiazide as model compound. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2008;46:335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2007.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Denisov IG, Mak PJ, Makris TM, Sligar SG, Kincaid JR. Resonance Raman characterization of the peroxo and hydroperoxo intermediates in cytochrome P450. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2008;112:13172–13179. doi: 10.1021/jp8017875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Egawa T, Shimada H, Ishimura Y. Evidence for compound I formation in the reaction of cytochrome P450cam with m-chloroperbenzoic acid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;201:1464–1469. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spolitak T, Dawson JH, Ballou DP. Reaction of ferric cytochrome P450cam with peracids. Kinetic characterization of intermediates on the reaction pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20300–20309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501761200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newcomb M, Zhang R, Chandrasena RE, Halgrimson JA, Horner JH, Makris TM, Sligar SG. Cytochrome p450 compound I. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:4580–4581. doi: 10.1021/ja060048y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Egawa T, Proshlyakov DA, Miki H, Makino R, Ogura T, Kitagawa T, Ishimura Y. Effects of a thiolate axial ligand on the pi to pi* electronic states of oxoferryl porphyrins. A study of the optical and resonance Raman spectra of compounds I and II of chloroperoxidase. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2001;6:46–54. doi: 10.1007/s007750000181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spolitak T, Dawson JH, Ballou DP. Replacement of tyrosine residues by phenylalanine in cytochrome P450cam alters the formation of Cpd II-like species in reactions with artificial oxidants. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2008;13:599–611. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hurshman AR, Krebs C, Edmondson DE, Huynh BH, Marletta MA. Formation of a Pterin radical in the reaction of the heme domain of inducible nitric-oxide synthase with oxygen. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15689–15696. doi: 10.1021/bi992026c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei CC, Crane BR, Stuehr DJ. Tetrahydrobiopterin radical enzymology. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2365–2383. doi: 10.1021/cr0204350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei CC, Wang ZQ, Hemann C, Hille R, Stuehr DJ. A tetrahydrobiopterin radical forms and then becomes reduced during No-mega-hydroxyarginine oxidation by nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46668–46673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307682200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wei C-C, Wang Z-Q, Wang Q, Meade AL, Hemann C, Hille R, Stuehr DJ. Rapid kinetic studies link tetrahydrobiopterin radical formation to heme-dioxy reduction and arginine hydroxylation in inducible nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:315–319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008441200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woodward JJ, Nejatyjahromy Y, Britt RD, Marletta MA. Pterin-centered radical as a mechanistic probe of the second step of nitric-oxide synthase. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5105–5113. doi: 10.1021/ja909378n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stoll S, NejatyJahromy Y, Woodward JJ, Ozarowski A, Marletta MA, Britt RD. Nitric-oxide synthase stabilizes the tetrahydrobiopterin cofactor radical by controlling its protonation state. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:11812–11823. doi: 10.1021/ja105372s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bec N, Gorren AFC, Mayer B, Schmidt PP, Andersson KK, Lange R. The role of tetrahydrobiopterin in the activation of oxygen by nitric-oxide synthase. J Inorg Biochem. 2000;81:207–211. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)00104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mathieu D, Frapart YM, Bartoli JF, Boucher JL, Battioni P, Mansuy D. Very general formation of tetrahydropterin cation radicals during reaction of iron porphyrins with tetrahydropterins. Model for the corresponding NO-synthase reaction. Chem. Commun (Camb) 2004;2004:54–55. doi: 10.1039/b312441j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schulz CE, Rutter R, Sage JT, Debrunner PG, Hager LP. Mössbauer and electron paramagnetic resonance studies of horse-radish peroxidase and its catalytic intermediates. Biochemistry. 1984;23:4743–4754. doi: 10.1021/bi00315a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rutter R, Hager LP, Dhonau H, Hendrich M, Valentine M, Debrunner P. Chloroperoxidase compound I. Electron paramagnetic resonance and Mössbauer studies. Biochemistry. 1984;23:6809–6816. doi: 10.1021/bi00321a082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jentzen W, Ma JG, Shelnutt JA. Conservation of the conformation of the porphyrin macrocycle in hemoproteins. Biophys J. 1998;74:753–763. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)74000-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Olea C, Jr, Kuriyan J, Marletta MA. Modulating heme redox potential through protein-induced porphyrin distortion. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12794–12795. doi: 10.1021/ja106252b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martin NI, Woodward JJ, Winter MB, Beeson WT, Marletta MA. Design and synthesis of C5 methylated l-arginine analogues as active site probes for nitric-oxide synthase. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12563–12570. doi: 10.1021/ja0746159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mitchell R, Rich PR. Proton uptake by cytochrome c oxidase on reduction and on ligand binding. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1994;1186:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(94)90130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]