Abstract

Evidence in humans and rodents suggests the importance of circadian rhythmicity in parturition. A molecular clock underlies the generation of circadian rhythmicity. While this molecular clock has been identified in numerous tissues, the expression and regulation of clock genes in tissues relevant to parturition is largely undefined. Here, we examine the expression and regulation of the clock genes Bmal1, Clock, Cry(Cryptochrome)1/2, and Per(Period)1/2 in the murine gravid uterus, placenta, and fetal membranes during late gestation. All clock genes examined were expressed in the tissues of interest throughout the last third of gestation. Upregulation of a subset of these clock genes was observed in each of these tissues in the final two days of gestation. Oscillating expression of mRNA for a subset of the examined clock genes was detected in the gravid uterus, placenta, and fetal membranes. Furthermore, bioluminescence recording on explants from gravid Per2::luciferase mice indicated rhythmic expression of PER2 protein in these tissues. These data demonstrate expression and rhythmicity of clock genes in tissues relevant to parturition indicating a potential contribution of peripheral molecular clocks to this process.

Introduction

Successful parturition is necessary for survival of the species. Mammalian species exhibit a tendency to begin labor and deliver at a characteristic time of day. Moreover, the study of female shiftworkers indicates that disruption of circadian rhythmicity may lead to preterm labor and low birth weight (Knutsson 2003). These observations suggest that parturition may be a circadian controlled process.

Circadian rhythmicity is generated by the oscillating expression levels of clock genes (Reppert and Weaver 2002). Transcriptional feedback loops help drive these oscillations. The CLOCK:BMAL1 heterodimer drives transcription of a group of genes including the Period(Per) and Cryptochrome(Cry) genes by binding to E-box enhancers. PER and CRY complex and inhibit the ability of the CLOCK:BMAL1 heterodimer to act as an enhancer, thus shutting down their own transcription (Reppert and Weaver 2002). Post-translational modification, notably phosphorylation, of clock proteins also plays a role in driving the molecular clock (Reppert and Weaver 2002).

The clock genes are expressed not only in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), which is regarded as the masterclock of the organism, but also in numerous other peripheral tissues. Clock genes in the retina (Storch et al. 2007) and skeletal muscle (McDearmon et al. 2006) have been shown to have roles independent of clock genes expressed in the SCN. Rhythmic expression of clock genes has been noted in female reproductive tissues including the ovary (Karman and Tischkau 2006), oviduct (Kennaway et al. 2003), and uterus (Dolatshad et al. 2006) of non-gravid rodents (reviewed in (Dolatshad et al. 2009). Little information exists on the presence of the molecular clock in tissues involved in the resolution of pregnancy such as the gravid uterus and specific tissues of the conceptus.

Previous studies on rhythmic clock gene expression in the conceptus have focused on the fetal SCN. The mouse fetal SCN develops between days 12 and 15 of gestation (Kabrita and Davis 2008), and exhibits circadian oscillation of Per1 transcript by day 17 of gestation (Shimomura et al. 2001). One study using in vivo bioluminescent imaging of pregnant Per1::luciferase rats indicated expression of Per1 in the fetus by day 10 of gestation and diurnal fluctuation in the expression of Per1 by day 12 (Saxena et al. 2007). However, in this study it was not possible to determine the fetal tissues that contributed to the gene expression observed.

Rodent studies indicate a role for clock genes in the resolution of pregnancy. An impact of maternal SCN-lesioning on the timing of labor in rats has been demonstrated. For normal rats, the onset of labor occurs with two peaks of frequency 24 hours apart on days 21 and 22 of gestation. SCN-lesioned rats, however, labor during this same time period with a single peak in frequency midway between the two normal peak times (Reppert et al. 1987). This indicates a role in parturition initiation for the central molecular clock located in the SCN. ClockΔ19 mutant mice, which have a deletion in the transcriptional activation domain of Clock resulting in dominant-negative function in all tissues, display high incidences of midgestational fetal resorption and extended but nonproductive labor (Miller et al. 2004). These studies suggest a potential role for genes of the molecular clock in regulating the onset and progression of parturition.

The presence of peripheral molecular clocks in the gravid uterus and non-SCN tissues of the conceptus has not previously been described. In the present report, we examine the expression of clock genes in the gravid mouse uterus, placenta, and fetal membranes during late gestation. We find that the core clock genes are expressed throughout the final third of gestation in these tissues. In many cases, expression of clock genes is rhythmic and regulated with respect to progression through gestation. Therefore, peripheral molecular clocks exist in tissues relevant to parturition.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals

Male and female C57BL/6/SvJ/129 mixed, C57BL/6, and knock-in mice (congenic on C57Bl/6J) expressing a mPeriod2::luciferase (Per2::Luc) fusion protein (Yoo et al. 2004) were fed ad libitum and maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle. Lights on was designated as ZT 0. Females in C57BL/6/SvJ/129 × C57BL/6/SvJ/129, C57BL/6 × C57BL/6, and Per2::luc × Per2::luc matings were checked for presence of a copulatory plug the morning after mating. Morning of the plug (1000 h, ZT 4) was noted as 0.5 days post-coitum (dpc) and the female was removed from the cage with the male. While for late gestational profiling and PER2 bioluminescence studies mating was continuous until plug detection, for circadian profiling females were mated to males for a limited time window of four hours nightly. This was done in order to facilitate detection of small fold change differences in transcript over the circadian day in tissues from these females. All animal experimentation described was conducted in accordance with accepted standards of humane animal care and was approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee.

Real-time qPCR

Uterus, placenta, and fetal membranes (amnion/chorion) were harvested from gravid C57BL/6/SvJ129 females for late gestational profiling and C57BL/6 females for circadian profiling, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until processing. For late gestational profiling, tissues were collected at ZT 4 (.5 dpc samples) or ZT 12 (.0 dpc samples) (n=3 animals per timepoint). For circadian day profiling, samples were collected at specified ZTs (n=3 animals per timepoint). Total RNA was extracted from tissue samples using TriZol reagent (Invitrogen). RNA from individual samples was converted to cDNA using Quantitect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen), which includes a step for elimination of genomic DNA. Previously reported forward and reverse primers for Bmal1, Clock, Cry1, Cry2, Per2 (Yang et al. 2006), Per1 (Yamamoto et al. 2005), Dbp (Noshiro et al. 2005), and Actg(Actin) (Duncan et al. 2006) were used. The amplification efficiency of these primers was verified as described by the system manufacturer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Forward and reverse Gapdh(glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) primers were designed using Primer Express software. These primers were validated for use with real-time qPCR by determining amplification efficiency and optimal primer conditions as described by the system manufacturer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Gapdh was used for standardization in all experiments except for the late gestational profiling of clock gene expression in the fetal membranes because this gene was upregulated in this tissue on the final days of gestation. In these studies, Actg primers were used for standardization. All primer sequences are reported in Table 1. Reactions were completed on the Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System. PCR conditions were as follows: one cycle at 50°C for 2 minutes, one cycle at 95°C for 10 minutes, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for one minute. A subsequent step to generate a dissociation curve was used to verify that a single amplicon was generated. Reactions were prepared using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and 500 nM each of forward and reverse Dbp primers, 900 nM each of forward and reverse Gapdh primers, or forward and reverse primers for other genes at concentrations previously described (Duncan et al. 2006; Yamamoto et al. 2005; Yang et al. 2006). Sequence Detection Software (v1.3.1) was used to determine the Ct value for each reaction. The ΔΔCt method was used for quantification (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). Statistical analysis was by one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test. Comparisons were considered statistically significant when p values were <0.05.

Table 1. Primers fur Real-Time qPCR.

| Gene | GenBank accession no. |

Primers | Reference (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bmal1 | NM_007489 | F: 5′-CCAAGAAAGTATGGACACAGACAAA-3′- R: 5′-GCATTCTTG ATGCTTCCTTGGT-3′ |

Yang et al. 2006 |

| Clock | NM_007715 | F: 5′-TTGCTCCACGGGAATCCTT-3′ R: 5′-GGAGGGAAAGTGCTCTGTTGTAG-3′ |

Yang et al. 2006 |

| Cry1 | NM_007771 | F: 5′-CTGGCGTGGAAGTCATCGT-3′ R: 5′-CTGTCCGCCATTGAGTTCTATG-3′ |

Yang et al. 2006 |

| Cry2 | NM_009963 | F: 5′-TGTCCCTTGCTGTGTGGAAGA-3′ R: 5′-GCTCCCAGCTTGGCTTGA-3′ |

Yang et al. 2006 |

| Per1 | NM_011065 | F: 5′-GAAAGAMCCTCTGGCTGTTCCT-3′ R: 5′-GCTGACGACGGATCTTTCTTG-3′ |

Yamamoto et al. 2005 |

| Per2 | NM_011066 | F: 5′-ATGCTCGCCATCCACAAGA-3′ R: 5′-GCGGAATCGAATGGGAGAAT-3′ |

Yang et al. 2006 |

| Dbp | NM_016974 | F: 5′-AGGAACTGAAGCCTCAACCAATC-3′ R: 5′-CTCCGGCTCCAGTACTTCTCAT-3′ |

Noshiro et al. 2005 |

| Gapdh | NM_008084 | F: 5′-ATTGTGGAAGGGCTCATGAC-3′ R: 5′-AGTGGATGCAGGGATGATGT-3′ |

|

| Actg | NM_009609 | F: 5′-GAAGGAGATCACAGOCCTAGCA-3′ R: 5′-GACAGTGAGGCCAGAATGGAG-3′ |

Duncan et al. 2006 |

Tissue Explant Culture and Bioluminescence Recording

Uterus, placenta, and fetal membranes (amnion/chorion) were harvested from each of three gravid Per2::luc females at ZT2-4 on the morning of 16.5 dpc (n=3 mice; 5-6 fetuses). Tissue explants were cultured in 1 ml of DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 0.1 mM beetle luciferin (Promega, Madison, WI) according to published methods (Abe et al. 2002). Placenta explants were placed on Millicell membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Each explant was sealed in a 35 mm Petri dish with a coverslip and vacuum grease and maintained at 36°C in darkness. Bioluminescence was continuously monitored with a photomultiplier tube (Hamamatsu, Shizouka, Japan) for 4-6 days. Data sets were detrended by subtracting the 24-h running average from the raw data. We then added the mean of the raw bioluminescence to each trace and plotted this as detrended bioluminescence.

Results

Expression and regulation of clock genes in the final third of gestation

To determine whether clock genes are expressed and regulated in parturition-relevant tissues as gestation progresses, expression of Bmal1, Clock, Cry1/2, and Per1/2 was evaluated in uterus, placenta, and fetal membranes from females 14.5 to 19.0 dpc by real-time qPCR (n=3 mice per timepoint). Parturition was expected to occur at approximately 19.5 dpc. Tissues were harvested at ZT 4 (.5 dpc timepoints) or ZT12 (.0 dpc timepoints).

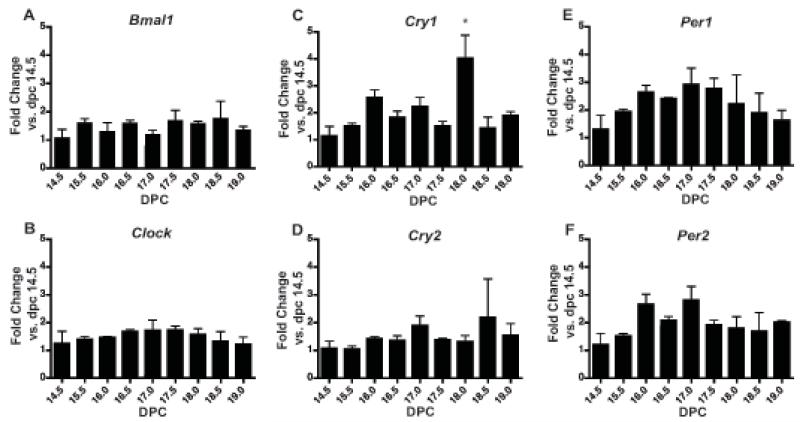

In the uterus, expression of all examined genes was noted by 14.5 dpc and persisted through 19.0 dpc (Figure 1A-F). In the uterus, Cry1 was the only gene to undergo significant changes over the final third of gestation (p<0.05; one-way ANOVA), with an increase at 18.0 dpc (p<0.05 vs. 14.5, 15.5, 16.5, 17.5, 18.5, and 19.0 dpc) (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Clock gene expression in uterus during late gestation.

Pregnant female mice were sacrificed at 9 timepoints during the final third of gestation starting with 14.5 dpc and ending on 19.0 dpc. Tissues were collected from three females per timepoint and analyzed for mRNA expression by real-time qPCR. Expression is normalized to Gapdh. Expression of A) Bmal1, B) Clock, C) Cry1 (p<0.05; one-way ANOVA), D) Cry2, E) Per1, and F) Per2 mRNA. Values are means +SEM. *denotes timepoints significantly different from others by Bonferroni’s post hoc test, p<0.05.

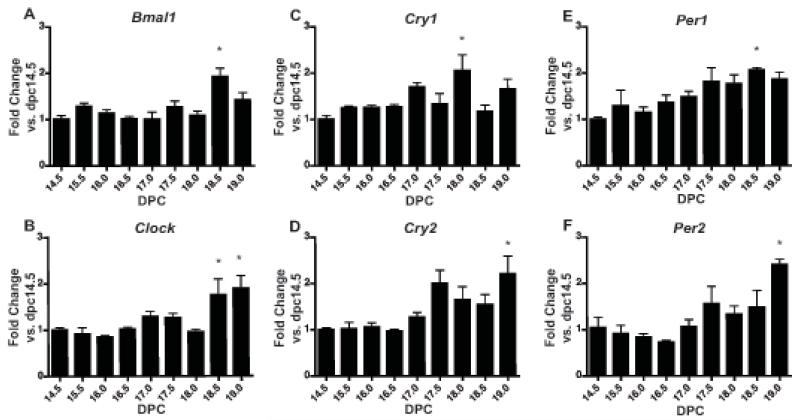

Expression and significant changes in each of the genes examined was observed over the final third of gestation in the placenta (p<0.05; one-way ANOVA) (Figure 2A-F). An increase in Bmal1 expression was observed at 18.5 dpc (p<0.05 vs. 14.5, 15.5, 16.0, 16.5, 17.0, 17.5, and 18.0 dpc) (Figure 2A). Clock expression was increased at 18.5 dpc (p<0.05 vs. 16.0) and 19.0 dpc (p<0.05 vs. 14.5, 15.5, 16.0, 16.5, and18.0 dpc) (Figure 2B). Cry1 expression was increased at 18.0 dpc (p<0.05 vs. 14.5 dpc) (Figure 2C). Cry2 expression was increased at 19.0 dpc (p<0.05 vs. 14.5, 15.5, 16.0, and 16.5 dpc) (Figure 2D). Per1 expression was increased at 18.5 dpc (p<0.05 vs. 14.5 dpc) (Figure 2E). Per2 expression was increased at 19.0 dpc (p<0.05 vs. 14.5, 15.5, 16.0, 16.5, and 17.0 dpc) (Figure 2F).

Figure 2. Clock gene expression in placenta during late gestation.

Pregnant female mice were sacrificed at 9 timepoints during the final third of gestation starting with 14.5 dpc and ending on 19.0 dpc. Tissues were collected from three females per timepoint and analyzed for mRNA expression by real-time qPCR. Expression is normalized to Gapdh. Expression of A) Bmal1, B) Clock, C) Cry1, D) Cry2, E) Per1, and F) Per2 mRNA. Changes in expression of each of these genes over the time period analyzed were significant (p<0.05; one-way ANOVA). Values are means +SEM. *denotes timepoints significantly different from others by Bonferroni’s post hoc test, p<0.05.

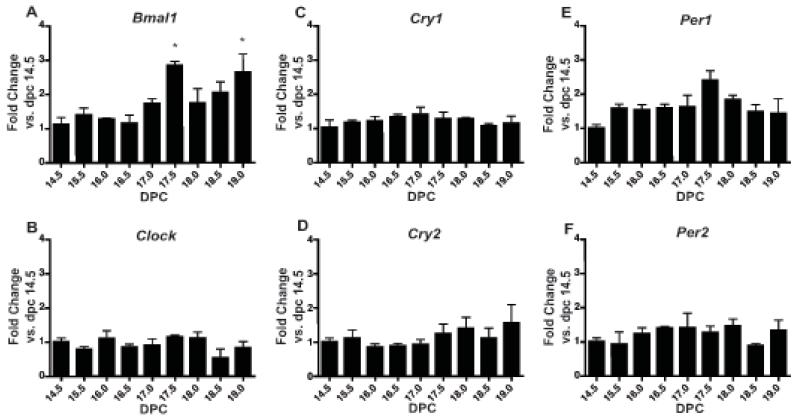

Likewise, expression of all examined clock genes was observed in the fetal membranes by 14.5 dpc and persisted through 19.0 dpc (Figure 3A-F). Significant changes in expression over the final third of gestation were noted only in Bmal1 (p<0.05; one-way ANOVA). Bmal1 expression was increased at 17.5 dpc (p<0.05 vs. 14.5, 16.0, and 16.5 dpc) and 19.0 dpc (p<0.05 vs. 14.5 dpc) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Clock gene expression in fetal membranes during late gestation.

Pregnant female mice were sacrificed at 9 timepoints during the final third of gestation starting with 14.5 dpc and ending on 19.0 dpc. Tissues were collected from three females per timepoint and analyzed for mRNA expression by real-time qPCR. Expression is normalized to Actg. Expression of A) Bmal1 (p<0.05; one-way ANOVA), B) Clock, C) Cry1, D) Cry2, E) Per1, and F) Per2 mRNA. Values are means +SEM. *denotes timepoints significantly different from others by Bonferroni’s post hoc test, p<0.05.

Circadian oscillation of clock gene transcripts during late gestation

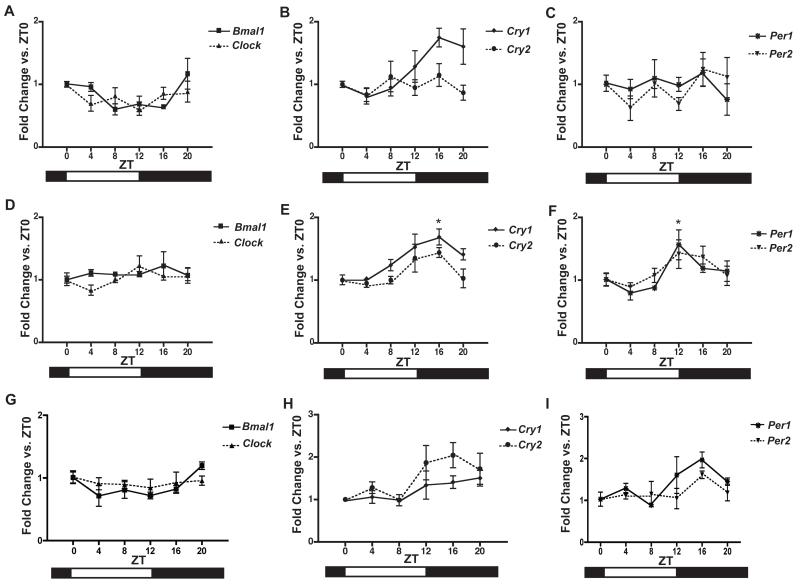

To determine whether clock gene transcript expression is rhythmic in uterus, placenta, and fetal membranes during late gestation, expression of Bmal1, Clock, Cry1/2, and Per1/2 was evaluated at 4-hour intervals during day 16 of gestation by real-time qPCR (n=3 mice per timepoint).

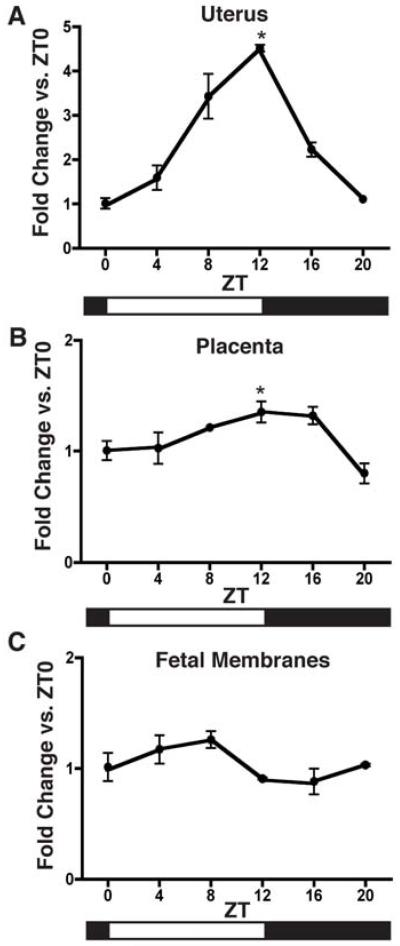

In the uterus, significant circadian changes were noted only in expression of Cry1 (p<0.05; one-way ANOVA), with changes in Bmal1 approaching significance (p=0.053; one-way ANOVA) (Figure 4A-C). In placenta, significant changes in Cry1 and Per1 were noted over the course of the day (p<0.05; one-way ANOVA), with changes in Cry2 approaching significance (p=0.053; one-way ANOVA) (Figure 4D-F). For Cry1, the observed maxima at ZT 16 is significantly different from the minima at ZT 0 and ZT 4 (p<0.05). Likewise, the Per1 maxima at ZT 12 is significantly different from the minima at ZT 4 (p<0.05). In the fetal membranes, changes in Bmal1, Cry2, and Per1 were observed with respect to time of day (p<0.05; one-way ANOVA) (Figure 4G-I).

Figure 4. Clock gene expression in gravid uterus, placenta, and fetal membranes from 16.0-17.0 dpc.

Pregnant female mice were sacrificed at 4-hour intervals during day 16 of gestation at ZT0, ZT4, ZT8, ZT12, Z16, and ZT20. Tissues were collected from three females per timepoint and analyzed for mRNA expression by real-time qPCR. Expression is normalized to Gapdh. Expression of A) Bmal1 (p=0.053; one-way ANOVA) and Clock, B) Cry1 (p<0.05; one-way ANOVA) and Cry2, and C) Per1 and Per2 in uterus. Expression of D) Bmal1 and Clock, E) Cry1 (p<0.05; one-way ANOVA) and Cry2 (p=0.053; one-way ANOVA), and F) Per1 (p<0.05; one-way ANOVA) and Per2 in placenta. Expression of G) Bmal1 (p<0.05; one-way ANOVA) and Clock, H) Cry1 and Cry2 (p<0.05; one-way ANOVA), and I) Per1 (p<0.05; one-way ANOVA) and Per2 in fetal membranes. Values are means +SEM. *denotes peaks significantly different from nadirs by Bonferroni’s post hoc test, p<0.05.

The transcript expression of the clock-regulated gene Dbp was also examined in the uterus, placenta, and fetal membranes during day 16 of gestation. Dbp transcription is known to be controlled by binding of the CLOCK:BMAL1 heterodimer to E-box enhancers in the gene (Ripperger and Schibler 2006); therefore oscillations in Dbp support that the molecular clock is functioning. Significant differences (p<0.05; one-way ANOVA) in Dbp expression over the circadian day were observed in uterus and placenta (Figure 5A&B). In uterus, the maxima at ZT 12 is significantly different from the minima at ZT 0 (p<0.001). In placenta, the maxima at ZT 12 is significantly different from the minima at ZT 20 (p<0.05). Changes observed over the circadian day in the fetal membranes were not significant (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. Dbp expression in gravid uterus, placenta, and fetal membranes from 16.0-17.0 dpc.

Pregnant female mice were sacrificed at 4-hour intervals during day 16 of gestation at ZT0, ZT4, ZT8, ZT12, Z16, and ZT20. Tissues were collected from three females per timepoint and analyzed for mRNA expression by real-time qPCR. Expression is normalized to Gapdh. Expression of Dbp in A) uterus (p<0.05; one-way ANOVA), B) placenta (p<0.05; one-way ANOVA), and C) fetal membranes. Values are means +SEM. *denotes peaks significantly different from nadirs by Bonferroni’s post hoc test, p<0.05.

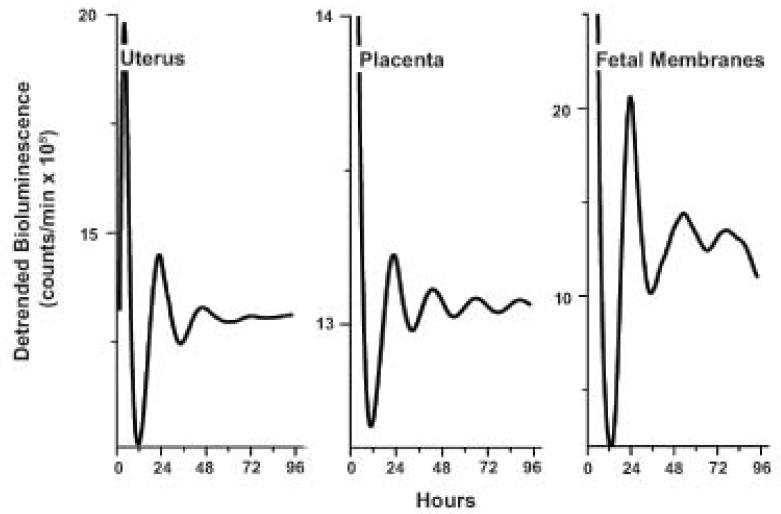

Circadian oscillation of PER2 protein during late gestation

The circadian oscillations of clock gene mRNA detected in late gestation may or may not translate to oscillation in protein. To examine potential circadian oscillations in PER2, tissue explants from three homozygous Per2::luc dams at 16.5 dpc were subjected to bioluminescence recording. Uterus, placenta, and fetal membranes all showed damped circadian bioluminescence indicating rhythmic expression of PER2 protein (Figure 6). Using the daily peak bioluminescence as a phase marker, we found the periods of uterine (21.4 +/− 5.2 h, n=4 explants), fetal membranes (21.2 +/− 2.3 h, n=5), and placental explants (19.5 +/− 1.8 h, n=4) did not differ (p>0.05, One-way ANOVA). These tissues reached their first peak of bioluminescence between 0.7 and 3.5 h after explantation, around the time of projected dusk.

Figure 6. PER2 rhythms in gravid uterus, placenta, and fetal membranes.

Representative Per2::luc bioluminescence recordings from cultured A) uterus, B) placenta, and C) fetal membranes. Recordings were taken from tissues harvested from each of three pregnant Per2::luc females.

Discussion

Given the known circadian gating to the timing of birth and disturbances to the progression of labor in ClockΔ19 females (Miller et al. 2004), we hypothesized that peripheral molecular clocks exist in tissues relevant to parturition. This report indicates that clock genes are expressed in the murine gravid uterus, placenta, and fetal membranes. In many cases clock gene expression is rhythmic and regulated with respect to progression through gestation.

Here we report, for the first time, evidence that the gravid uterus, placenta, and fetal membranes express genes of the molecular clock. Rhythmic expression of transcript for some, but not all, of the examined clock genes was observed in uterus, placenta, and fetal membranes over day 16 of gestation (Figure 4). While rhythmic expression of transcript was in many cases detected, it is possible that either our 4-hour intervals missed a peak in expression or our real-time qPCR conditions were not sensitive enough to detect lower amplitude rhythms of transcripts that appeared nonrhythmic. Alternatively, there may be a reliance on translational or post-translational control to generate rhythmicity of some of these genes in these tissues at this time. Rhythmic expression of PER2 in each of the examined tissues indicates that rhythmicity exists at the protein level (Figure 6). In uterus and placenta, rhythmic expression of transcript for Dbp, a clock-regulated gene, further indicates the presence of molecular clock function (Figure 5A&B).

In the uterus, circadian regulation of Cry1 transcript was observed (Figure 4B), with regulation of Bmal1 in antiphase to Cry1 approaching significance (Figure 4A). This pattern of expression is expected since in most tissues examined previously, Bmal1 cycles antiphase to negative regulators Cry and Per. Circadian expression of Bmal1, Cry1, and Per2 transcript has previously been examined in non-gravid mouse uterus (Dolatshad et al. 2006). The Cry1 profile of gravid uterus reported here is similar in magnitude and time of peak and nadir to data previously reported for non-gravid uterus (Dolatshad et al. 2006). However, some discrepancies exist between the previously reported non-gravid uterus data and the gravid uterus data presented here. The Bmal1 profile for gravid uterus has similar time of peak and nadir but smaller magnitude of change compared to that reported for non-gravid uterus (Dolatshad et al. 2006). While a circadian change in expression of Per2 transcript has been reported for non-gravid uterus (Dolatshad et al. 2006), we do not observe such a change in gravid uterus here. Given the numerous physiological and gene expression changes occurring in the uterus during gestation, such differences in regulation of clock genes is not unexpected.

In the placenta, circadian oscillation of Cry1 and Per1 was observed, with regulation of Cry2 approaching significance (Figure 4E&F). The oscillation observed in each of these genes in the placenta is in phase with one another as expected. The changes in expression observed in the placenta are of a similar magnitude as those observed in the uterus.

In the fetal membranes, oscillation in expression of Bmal1, Cry2, and Per2 were observed with respect to time of day (Figure 4G-I). These changes are similar in magnitude to gene expression changes observed in uterus and placenta. The changes in Bmal1 are antiphase to those seen in Cry2 and Per2.

Bioluminescent imaging of tissue explants from gravid Per2::luc females indicates oscillating expression of PER2 protein in gravid uterus, placenta, and fetal membranes (Figure 6). Significant oscillations in Per2 transcript were detected in the placenta, but not in the gravid uterus or fetal membranes. The observed oscillations of PER2 in the uterus and fetal membranes may therefore be a result of regulation at the translational or post-translational level. Oscillating clock protein levels in the presence of nonrhythmic transcript expression has been demonstrated previously (Fujimoto et al. 2006).

Regulation of clock genes as parturition approaches may support a role for these genes in the initiation of labor. Upregulation in transcript for some or all of the examined clock genes was observed over the final two days of gestation in the current study. In the uterus, Cry1 expression increases at day 18.0 (Figure 1). In the placenta, expression of each of the examined clock genes is observed between days 18.0 and 19.0 (Figure 2). In the fetal membranes, Bmal1 expression increases significantly at days 17.5 and 19.0 (Figure 3).

The timing of these inductions is consistent with a possible role for these genes in regulating the cascade of events controlling the initiation of parturition. These genes could be impacting parturition through either conventional clock effects or a previously undetermined nonconventional effect. Because clock gene conventional knockout and mutant mice are subfertile or infertile (Alvarez et al. 2008; Chappell et al. 2003; Herzog et al. 2000; Kennaway et al. 2005; Ratajczak et al. 2009), conditional clock gene knockout mice will be important in ascertaining the role of clock genes in parturition.

Roles of molecular clock genes specific to peripheral tissues have been demonstrated (McDearmon et al. 2006; Storch et al. 2007). We report here that molecular clocks exist in tissues important to parturition. Clock genes thus have the potential to impact parturition. Dissecting the roles of clock genes in peripheral tissues may lead to new insights into this critical but poorly understood process.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sherri Vogt, Crystal Kelley, and Tatiana Simon for technical assistance. Support from NIMH 63104 (EDH).

Funding

This work was supported by the Center for Preterm Birth Research at Washington University in St. Louis.

References

- Abe M, Herzog ED, Yamazaki S, Straume M, Tei H, Sakaki Y, Menaker M, Block GD. Circadian rhythms in isolated brain regions. J Neurosci. 2002;22:350–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00350.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez JD, Hansen A, Ord T, Bebas P, Chappell PE, Giebultowicz JM, Williams C, Moss S, Sehgal A. The circadian clock protein BMAL1 is necessary for fertility and proper testosterone production in mice. J Biol Rhythms. 2008;23:26–36. doi: 10.1177/0748730407311254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell PE, White RS, Mellon PL. Circadian gene expression regulates pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretory patterns in the hypothalamic GnRH-secreting GT1-7 cell line. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11202–13. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-35-11202.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolatshad H, Campbell EA, O’Hara L, Maywood ES, Hastings MH, Johnson MH. Developmental and reproductive performance in circadian mutant mice. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:68–79. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolatshad H, Davis FC, Johnson MH. Circadian clock genes in reproductive tissues and the developing conceptus. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2009;21:1–9. doi: 10.1071/rd08223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan JL, Yang H, et al. Scotopic visual signaling in the mouse retina is modulated by high-affinity plasma membrane calcium extrusion. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7201–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5230-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto Y, Yagita K, Okamura H. Does mPER2 protein oscillate without its coding mRNA cycling?: post-transcriptional regulation by cell clock. Genes Cells. 2006;11:525–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog ED, Grace MS, Harrer C, Williamson J, Shinohara K, Block GD. The role of Clock in the developmental expression of neuropeptides in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 2000;424:86–98. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000814)424:1<86::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabrita CS, Davis FC. Development of the mouse suprachiasmatic nucleus: determination of time of cell origin and spatial arrangements within the nucleus. Brain Res. 2008;1195:20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karman BN, Tischkau SA. Circadian clock gene expression in the ovary: Effects of luteinizing hormone. Biol Reprod. 2006;75:624–32. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.050732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennaway DJ, Boden MJ, Voultsios A. Reproductive performance in female Clock(Delta19) mutant mice. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2005;16:801–10. doi: 10.1071/rd04023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennaway DJ, Varcoe TJ, Mau VJ. Rhythmic expression of clock and clock-controlled genes in the rat oviduct. Mol Hum Reprod. 2003;9:503–7. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gag067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutsson A. Health disorders of shift workers. Occup Med (Lond) 2003;53:103–8. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqg048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDearmon EL, Patel KN, et al. Dissecting the functions of the mammalian clock protein BMAL1 by tissue-specific rescue in mice. Science. 2006;314:1304–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1132430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BH, Olson SL, Turek FW, Levine JE, Horton TH, Takahashi JS. Circadian clock mutation disrupts estrous cyclicity and maintenance of pregnancy. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1367–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noshiro M, Furukawa M, Honma S, Kawamoto T, Hamada T, Honma K, Kato Y. Tissue-specific disruption of rhythmic expression of Dec1 and Dec2 in clock mutant mice. J Biol Rhythms. 2005;20:404–18. doi: 10.1177/0748730405280195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczak CK, Boehle KL, Muglia LJ. Impaired steroidogenesis and implantation failure in Bmal1−/− mice. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1879–85. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reppert SM, Henshaw D, Schwartz WJ, Weaver DR. The circadian-gated timing of birth in rats: disruption by maternal SCN lesions or by removal of the fetal brain. Brain Res. 1987;403:398–402. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reppert SM, Weaver DR. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature. 2002;418:935–41. doi: 10.1038/nature00965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripperger JA, Schibler U. Rhythmic CLOCK-BMAL1 binding to multiple E-box motifs drives circadian Dbp transcription and chromatin transitions. Nat Genet. 2006;38:369–74. doi: 10.1038/ng1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena MT, Aton SJ, Hildebolt C, Prior JL, Abraham U, Piwnica-Worms D, Herzog ED. Bioluminescence imaging of period1 gene expression in utero. Mol Imaging. 2007;6:68–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura H, Moriya T, Sudo M, Wakamatsu H, Akiyama M, Miyake Y, Shibata S. Differential daily expression of Per1 and Per2 mRNA in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of fetal and early postnatal mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:687–93. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2000.01438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch KF, Paz C, Signorovitch J, Raviola E, Pawlyk B, Li T, Weitz CJ. Intrinsic circadian clock of the mammalian retina: importance for retinal processing of visual information. Cell. 2007;130:730–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Nakahata Y, Tanaka M, Yoshida M, Soma H, Shinohara K, Yasuda A, Mamine T, Takumi T. Acute physical stress elevates mouse period1 mRNA expression in mouse peripheral tissues via a glucocorticoid-responsive element. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42036–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509600200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Downes M, Yu RT, Bookout AL, He W, Straume M, Mangelsdorf DJ, Evans RM. Nuclear receptor expression links the circadian clock to metabolism. Cell. 2006;126:801–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH, Yamazaki S, et al. PERIOD2::LUCIFERASE real-time reporting of circadian dynamics reveals persistent circadian oscillations in mouse peripheral tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:5339–46. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308709101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]