Abstract

Background

Autism-spectrum disorders (ASD) are childhood neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by social and communicative impairment and repetitive and stereotypical behavior. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) is an upstream regulator of innate immunity that promotes monocyte/macrophage activation responses by increasing the expression of Toll-like receptors and inhibiting activation-induced apoptosis. Based on results of prior genetic linkage studies and reported altered innate immune response in ASD, we hypothesized that MIF could represent a candidate gene for ASD or its diagnostic components.

Methods

Genetic association between ASD and MIF was investigated in two independent sets of families of probands with ASD, from USA (527 participants from 152 families) and Holland (532 participants from 183 families). Probands and their siblings, when available, were evaluated with clinical instruments used for ASD diagnoses. Genotyping was performed for two polymorphisms in the promoter region of the MIF gene in both samples sequentially. In addition, MIF plasma analyses were carried out in a subset of Dutch patients from whom plasma was available.

Results

There were genetic associations between known functional polymorphisms in the promoter for MIF and ASD-related behaviors. Also, probands with ASD exhibited higher circulating MIF levels than did their unaffected siblings; the amount of MIF in the plasma correlated with the severity of multiple ASD symptoms.

Conclusions

These results identify MIF as a susceptibility gene for ASD. Further research is warranted on the precise relationship between MIF and the behavioral components of ASD, the mechanism by which MIF contributes to ASD pathogenesis, and the clinical utility of MIF genotyping.

The etiopathogenesis of autism-spectrum disorders (ASD) is unknown. ASD are considered among the most heritable neurodevelopmental disorders1 and are observed in 34 to 62.6 per 10,000 children2. There is also evidence for genetic transmission of milder autism-associated phenotypes and autism components3. Although multiple genome-wide scans have been conducted, results generally have been inconsistent. Chromosomal regions 7q and 10p are supported by meta-analytic4 and high-resolution scanning studies, respectively5, but other regions, including 22q6, 7, may confer susceptibility to ASD. Multiple candidate genes, including those controlling brain growth8, glutamatergic and GABAergic synaptogenesis5, and immune function9, also have been proposed to play a role. In appreciation of this mosaic of findings, the consensus hypothesis is that the etiology of ASD is predominantly oligogenic and likely includes gene–gene and gene–environment interactions.

Individuals with ASD can exhibit additional disorders, including seizures, gastrointestinal and neurological symptoms, and immunological deficiencies. The presence of immune abnormalities in patients with ASD has long been noted10. The relevant literature can be traced back some three decades to a report of a high frequency of autoimmune diseases in a family with a proband with ASD11. This report triggered family studies of the co-occurrence of ASD and autoimmune diseases and confirmation of the observation of elevated counts of autoimmune diseases when compared with control families12, 13. Additionally, indicators of chronic neuroinflammation have been reported in the brain14–17 and blood and urine18–21 of probands with ASD. The literature further describes abnormal cellular immune responses22–26 and other autoimmune abnormalities in probands with ASD27, 28. Also of interest are a variety of hypotheses linking the well-established hyperserotoninemia and immune abnormalities in ASD29. Finally, it is important to note that there have been a number of genetic studies investigating allelic association and linkage among genes or in the region of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and ASD; however, results of these studies are mixed, with some pointing to the presence of the association30, 31 and others excluding linkage32. Some studies suggest that innate rather than adaptive neuroimmune responses are associated with ASD. Thus, the literature on the presence of immune problems in probands with ASD and their families contains a critical mass of information for generating a hypothesis regarding the involvement of autoimmune genes in the etiopathogenesis of ASD. At present, views of possible immune dysfunction in ASD range from conclusions that it may contribute to manifestations of the disorder in some patients18 to hypotheses that neuroimmunopathogenic responses play a fundamental role in ASD33. Studies suggest that innate rather than adaptive neuroimmune responses are associated with ASD34.

Given a complex model of the inheritance of ASD, one possible etiopathic mechanism might involve an immunologic insult to the central nervous system (CNS) in individuals with a susceptible genetic background. We evaluated the genetic association between the innate mediator, macrophage migration inhibitory factor35 (MIF), and different behavioral components of ASD. MIF is encoded in a functionally polymorphic locus on chromosome 22q11.2 (OMIM 153620, GenBank accession no. NM_002415) that has been associated with the incidence or severity of different autoimmune inflammatory conditions36. Given its location in a previously identified locus of interest and its upstream action in immunity, MIF may represent a candidate gene for ASD or its components. Thus, the central hypothesis underlying this research was that a genetic predisposition to a particular level of MIF production, may lead to a pro-inflammatory profile of cell activation that, if present during a neurodevelopmentally sensitive period, might contribute to the etiopathogenesis of autism.

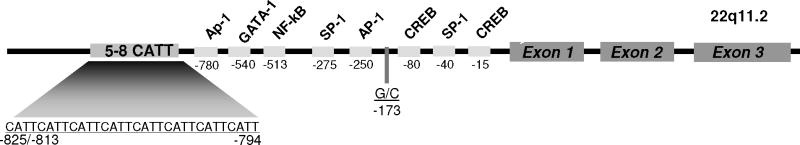

The MIF gene (see Figure 1) spans less than 1 Kb and is highly conserved. Several functional MIF alleles exist in the general population and differ in the structure of their promoter region. A CATT repeat (−794 CATT5–8) influences basal and stimulus-induced transcriptional activity such that transcription increases in an almost proportional fashion with repeat number37. The CATT5MIF allele is typically referred to as a “low expression” allele, and the CATT6, CATT7, and (rare) CATT8 MIF alleles are considered “higher expression” alleles. A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP, −173 G/C) is located within the same haplotype block as the CATT site and may exert a regulatory function by means of linkage disequilibrium or functional interaction with the repeat38.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the human MIF gene showing its three exons, predicted transcription factor binding sites, and the −173 SNP and −794 CATT polymorphisms.

METHODS

Patients

Two sets of families, one recruited through the Yale University Child Study Center (YCSC) in the United States and the other through the University Center for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Accare/University Medical Center Groningen in the Netherlands, contributed to this work. Clinical characterization of these families has previously been described39. All research was approved by corresponding Institutional Review Boards and appropriate consent forms were obtained.

The US samples included 527 individuals from 152 families ascertained through a proband with ASD assessed at the clinics of the YCSC39. The Dutch sample included 532 participants from 183 families who approached the Accare Center for evaluation purposes40. For more details on the samples, see Table 1. In the analyses presented here, only families of probands with autism and Asperger’s disorder were included.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics on the Samples of US and Dutch Families of the ASD Probands

| US | Dutch | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Total number of people genotyped | 472 | 528 |

| Male (%) | 62.3 | 61.7 |

| Female (%) | 37.7 | 38.3 |

| Ethnic background (%)1 | ||

| Caucasian | 95% | 100% |

| Ethnic minority | 5% | 0% |

| Number of probands per family | ||

| 1 | 129 | 183 |

| 2 | 21 | 0 |

| 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Average age of the probands | 10.97 | 9.85 |

| Probands’ Clinical Diagnoses2 | ||

| Autism | 84 | 88 |

| Asperger’s Disorder | 46 | 12 |

| CDD | 7 | 0 |

| PDD-NOS | 34 | 57 |

Notes:

The analyses for the US sample were carried out with and without families of minority ethnic background. Because the results were virtually identical, we here present the results for the ethnically admixed sample

Clinical diagnoses were obtained by consensus among practicing clinicians at both sites, respectively, based on opinions of at least two independent evaluators.

Probands and their siblings were evaluated with several clinical instruments used for ASD diagnosis [Autism Diagnostic Interview, ADI, multiple versions41; and Autism Diagnostic Observational Schedule, ADOS, multiple modules42], from which six phenotypes that capture different facets of ASD were generated as described below. In addition, all patients received clinical diagnoses (see Table 1).

Genotyping

Standard methods were used to extract DNA from blood collected in EDTA or from buccal mucosa cells. Analysis of the collected samples for the CATT MIF polymorphism was performed as previously described37, and the fluor-labeled amplicons were resolved using an ABI 3100 Genetic Analyzer. DNA from previously genotyped homozygous individuals was used to generate control amplicons for size calibration for capillary electrophoresis. The −173 G/C alleles were determined by TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assays on the ABI Prism 7900HT and analyzed with SDS software. The probe was obtained from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). The two samples were genotyped sequentially, with the US sample considered the initial discovery sample and the Dutch sample the replication sample43. The genotyping was separated by about eight months and was carried out on the same machinery with the same control DNAs.

Variable Description

As prescribed by corresponding manuals, using all designated items, the administration of the ADI resulted in three subscores (ADI social, ADI communication, and ADI stereotypical behaviors). The administration of the ADOS resulted in four subscores (ADOS social, ADOS communication, ADOS stereotypical behaviors, and ADOS imaginative skills). For each of the three presumed latent traits (social, communication, and stereotypical facets of ASD), we formed combinations of measured scores capturing that latent trait and analyzed the resulting vectors of measured scores with multivariate association models (phenotypes 1–3, see Table 3). Thus, the social phenotype was a vector of ADI social and ADOS social; the communication phenotype consisted of the two communication scores from the ADI and ADOS, and finally, the stereotypical behaviors phenotype consisted of the two summative scores from ADI (restricted/repetitive behaviors) and ADOS (stereotyped behaviors). This construction of phenotypes was done for two reasons: (1) to maximize on the convergence between different instruments to decrease the amount of error in assessing different facets of ASD; and (2) to minimize the number of phenotypes investigated and, correspondingly, to decrease the probability of Type I error increasing as the number of multiple comparisons increased. Before conducting genetic association tests, we regressed each trait on age and gender and transformed the phenotypes using rank transformation. For phenotypes 1–3 (Table 3), we used these residuals as phenotypes in input data files for association analyses. In addition, we regressed each of these three phenotypes on two other domain phenotypes and used the residuals as the phenotype in input data (e.g., regressing ADOS stereotypical behaviors on ADOS communication and ADOS social; all three were already regressed on age and gender). Specifically, phenotype (1) was considered when the variance attributable to indicators of language/communication impairments and stereotypical behaviors (as captured by the corresponding variables described earlier: 2 from the ADOS and 2 from the ADI) were removed (the resulting residualized phenotype is designated as phenotype 4 in Table 3). Similarly, phenotype (2), impairment in language/communication, was considered when we residualized measures of social interaction and stereotypical (or restricted interests/repetitive) behaviors from the ADOS and ADI (see phenotype 5 in Table 3). Finally, phenotype (3) was analyzed when the ADOS and ADI indicators of social interaction and communication/language functioning were removed (see phenotype 6 in Table 3). Such redisualization permitted us to (1) focus on specific variance associated with a particular facet of ASD, when variance attributable to other facets was regressed out; and (2) once again, minimize the number of multiple comparisons.

Table 3.

Results (P values) of multivariate association analyses for the six autism-related phenotypes and two MIF markers in the US sample under the null hypothesis of no association by PBAT.

| Phenotypes | Additive Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CATT5 | CATT6 | CATT7 | SNP (C vs. G) | |

| Discovery (US) Sample | ||||

| Social Impairment (1) | .21977 | .07191 | .41436 | .21733 |

| Communication Impairment (2) | .25319 | .13250 | .40131 | .23507 |

| Stereotypical Behaviors (3) | .00584 | .00259 | .56716 | .81854 |

| Social Impairment–R (4) | .07207 | .05609 | .51668 | .82883 |

| Communication Impairment–R (5) | .23247 | .37857 | .17543 | .27731 |

| Stereotypical Behaviors–R (6) | .00373 | .00009 | .28669 | .44593 |

| Replication (Dutch) Sample | ||||

| Social Impairment (1) | 0.61215 | 0.77958 | 0.21100 | 0.05278 |

| Communication Impairment (2) | 0.72255 | 0.48094 | 0.15405 | 0.03700 |

| Stereotypical Behaviors (3) | 0.45537 | 0.84091 | 0.30765 | 0.05638 |

| Social Impairment–R (4) | 0.91088 | 0.99357 | 0.95776 | 0.89561 |

| Communication Impairment–R (5) | 0.61608 | 0.18231 | 0.36073 | 0.82589 |

| Stereotypical Behaviors–R (6) | 0.11373 | 0.02973 | 0.34349 | 0.87544 |

Note:

We performed the analyses under the null hypotheses “no linkage and no association” under additive genetic models. The P-values shown in bold (US Sample) are less than 0.0071; the null hypothesis can be rejected at a simultaneous significance level of 0.05, corrected for multiple testing. The P-values shown in italics (Dutch Sample) are less than 0.05.

With these phenotypes, we carried out multivariate linkage and association analyses for the two polymorphisms in the MIF gene promoter separately for the two samples.

Association Analyses

We used the Family Based Association Tests (FBAT)44 software for univariate and haplotype tests. We also used the Tools for Family-Based Association Studies (PBAT)45 software, specifically the R library pbatR, for multivariate tests of the null hypothesis of “no association in the presence of linkage.”

Three rounds of analyses were performed. First, we executed an exploratory set of analyses on the US dataset with the six phenotypes described earlier. Because these analyses involved multiple comparisons, they were followed by a simulation study that generated new threshold empirical P-values for interpretation of the nominal P-values (see Table 2). We then analyzed the Dutch data as a confirmatory sample; correspondingly, we did not use adjustments for multiple comparisons. Finally, we completed a summative analysis of both samples, using a method initially proposed by Fischer46 and currently being advocated47 for combining results from multiple samples to establish gene-based association.

Table 2.

Allele frequencies at two MIF polymorphisms in the US and Dutch samples

| Allele frequencies | US | Dutch |

|---|---|---|

| CATT5 | 0.267 | 0.258 |

| CATT6 | 0.627 | 0.571 |

| CATT7 | 0.104 | 0.171 |

| CATT8 | 0.002 | |

| SNPC | 0.155 | 0.190 |

| SNPG | 0.845 | 0.810 |

Adjustments for Multiple Comparisons

The tests we performed for the several traits for each of several alleles in our discovery (US) sample led to multiple P values. To adjust for multiple comparisons and account for dependence among traits, we conducted a Monte Carlo simulation study designed to assess our results relative to the smallest P values that would arise by chance, assuming the truth of the null hypothesis, with our particular suite of statistical tests and with our particular trait and parental genotype data. We simulated 1,000 synthetic datasets according to the null hypothesis of no association, conditional on the minimal sufficient statistics identified by Rabinowitz and Laird48. To create each of the datasets, we simulated new random genotypes for the participants from the appropriate conditional distributions48 while fixing the trait measurements and parental genotypes at the values observed in our data. For each synthetic dataset, we then carried out the same statistical tests applied to our original dataset, creating a new table of P values. For each of the resulting 1,000 tables, we recorded the minimum P value, giving an empirical distribution of the minimum P value. The 5% quantile of that minimum P value distribution was 0.0071. Thus, the procedure of rejecting each of the null hypotheses whose P value in Table 3 (US portion) was less than 0.0071 has an overall significance level of 0.05, taking into account multiple testing.

Plasma MIF Analysis

MIF was measured by sandwich ELISA using specific antibodies and native sequence human MIF that was prepared in the Bucala laboratory as a standard49.

RESULTS

The allele frequencies in each sample and for both samples combined are shown in Table 2. The results of the association analyses are shown in Table 3. Because the CATT8 allele was not observed in the US data and had low frequency in the Dutch sample, it was not tested for association. We tested alleles CATT5, CATT6, and CATT7. Also of note is the degree of linkage disequilibrium between the −794 CATT and the −173 SNP, which was repeatedly high in both samples (D′=.57 and .72 in the US and Dutch samples, respectively).

US Sample

Our findings indicated the presence of a genetic association between the −794 CATT site and ASD. The strongest associations were between the −794 CATT6 MIF alleles and the stereotypical components of ASD, residualized (phenotype 6, P-value=0.00009), and non-residualized (phenotype 3, P-value=0.00259). We also performed univariate PBAT tests for each trait, which provided confirmatory information for the multivariate findings. Specifically, the CATT6 allele showed P-values lower than 0.05 for both ADOS stereotypical behaviors scores (P=0.00059 and 0.00022, before and after residualization, respectively).

Dutch Sample

The Dutch sample was treated as a confirmatory sample analysis; a number of multivariate phenotypes provided support to the genetic association with MIF. Specifically, consistently with the results of the US sample, the stereotypical components of ASD, residualized (phenotype 6), gave a P-value of 0.02973 with CATT6. In this sample, the −173 SNP also generated statistically significant or borderline P-values for nonresidualized multivariate phenotypes of social impairment (phenotype (1), P=0.05278), communication impairment (phenotype 2, P=.03700), and stereotypical behaviors (phenotype 3, P=0.05638). The genetic associations with MIF were further supported in the Dutch sample by univariate analyses. Specifically, the −173 SNP polymorphism appeared to be associated with all ADI and ADOS unresidualized phenotypes (ADI: P-values of 0.01698, 0.02208, and 0.017103 and ADOS: 0.025062, 0.011041. and 0.024524, for social impairment, communication impairment, and stereotypical behaviors, respectively).

To summarize the patterns of results across the two samples, we applied Fisher’s product criterion46, 50, which allows unifying different P-values obtained for different alleles across the two samples in a meta-analytic fashion. Specifically, we combined P-values for the two residualized multivariate phenotypes (stereotypical behaviors and stereotypical behaviors–residualized) that survived the correction for multiple comparisons in the US sample and for the two univariate phenotypes (ADI and ADOS stereotyped behaviors) that contributed to these two multivariate phenotypes. The corresponding US–Dutch combined Fisher P-values were P=0.01649 and P=0.00047 for multivariate phenotypes. For univariate phenotypes, the ADOS-based indicators gave statistically significant P-values (P=0.00217 and P=0.01749, for stereotypical behaviors and stereotypical behaviors–residualized).

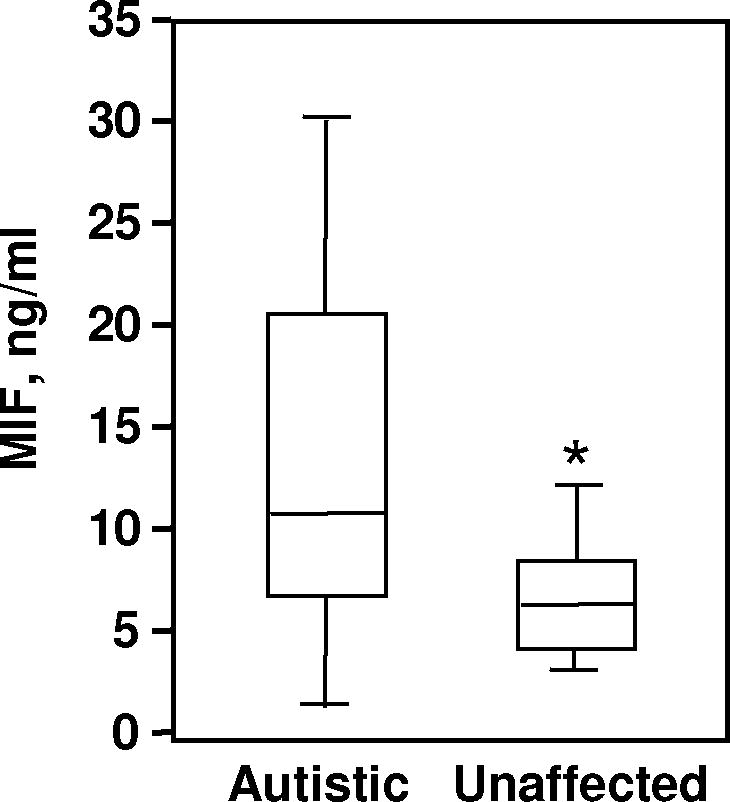

Plasma Analyses

We also measured levels of plasma MIF protein49 in 10 probands51 and their unaffected siblings from the Dutch sample. A significantly higher level of circulating MIF in the ASD-affected group (ASD: 13.12±9.18 ng/ml; unaffected siblings: 6.87±2.75 ng/ml; Mean±SD, P=0.0323, Figure 2) provided independent corroboration of the genetic association findings.

Figure 2.

Boxplots of the plasma concentrations of MIF in probands and their unaffected siblings (n=10 per group). The bottom, median, and top lines of the box demarcate the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles, respectively. The vertical lines show the minimum and maximum values. *P=0.0323 for autistic group vs. unaffected siblings (T-test, unpaired).

Moreover, when the plasma MIF protein in 29 probands (10 from the previous sib comparison and 19 assayed additionally) was correlated with behavioral indicators, statistically significant positive correlations were obtained between plasma MIF levels and ADOS scores on social impairment, imaginative skills, and total score (r=0.41, 0.41, and 0.39, respectively, P<0.05 for all). The correlation with the ADOS stereotypical behavior score did not reach statistical significance (r=0.15, P>0.10), but trended in the same direction.

DISCUSSION

Collectively, these data identify MIF as a potential ASD susceptibility gene and support earlier suggestions of a role for innate immunity in the etiopathogenesis of this disease. These data include evidence for neuroglial and innate immune activation in brain tissue and cerebrospinal fluid17 and increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the CNS or blood of patients with ASD52. Persistent elevation of cytokines in the CNS may reflect an ongoing inflammatory process, microglial activation, or developmental arrest, as some cytokine levels increase during phases of neurodevelopment34. Because MIF regulates the expression of innate cytokines35, we hypothesize that a genetic predisposition at the MIF locus may lead to an inappropriate level of MIF production during a neurodevelopmentally sensitive period, contributes to the pathogenesis of ASD. Our data add to the evidence that some innate immunity genes may play an important role in the development of ASD9.

Although numerous studies have linked high-expression MIF alleles with autoimmune diseases35, 37, 49, 53, a specific role for MIF in CNS disorders has not been described previously and it may be relevant that MIF is also expressed by neuronal cells. In vitro studies have shown that the intracellular content of MIF increases during neuronal firing and then acts to reduce the chronotropic effects of further stimulation54. Thus, the role of the known variant MIF alleles in ASD may involve neuronal functions that extend beyond the protein’s well-described immunologic actions35. Pharmacologic inhibitors of MIF are presently in pre-clinical development55, 56 and therapies aimed specifically at MIF pathways in patients with ASD might be feasible.

In summary, we present evidence for an association between the MIF locus and ASD, specifically with the stereotypical components of ASD. Because ASD are heterogeneous in presentation and etiology, it is possible that different genes underlie the manifestation of different facets of ASD. Given that distinctive diagnostic components of ASD show differential heritability estimates and patterns of familial transmission and, thus, may be fractionable3, 57, these components may be associated with different etiopathogeneses. In the overwhelming majority of (if not all) studies of immunological abnormalities in ASD, phenotyping was restricted to clinical diagnoses (affected vs. unaffected) based on DSM criteria. Some inconsistencies in the immunological research results on ASD may be due to cross-study differences in phenotyping and failure to study specific phenotypes of ASD. If our findings, in which immunological abnormalities are mostly associated with particular facets of ASD, are replicated, this inconsistency may be explained. More generally, evidence of higher rates of autoimmunity (rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, asthma, allergies, thyroid disorders)34 in relatives of individuals with ASD suggests that additional immunologic response genes also should be tested for involvement in ASD.

These initial findings will require further study in other samples of probands with ASD in order to determine their replicability. In addition, an examination of samples of probands with other developmental disorders can provide an assessment of the specificity of the association between MIF genotype and ASD. These results also prompt a reconsideration of prior observations and stimulate the investigation of new hypotheses regarding relationships between early immune function and ASD, and possibly other developmental neuropsychiatric disorders. Determination of an MIF genotype or protein levels may assist in better defining ASD phenotypes, thereby improving the prognosis of behavioral abnormalities, and potentially enabling new pharmacologic interventions.

What’s Known on this Subject

ASD are clinically complex and characterized by many etiological pathways involving multiple genetic and environmental risk factors. Although a number of such risk factors have been proposed, no single factor has sustained the scrutiny of replications in multiple diverse samples.

What This Study Adds

The study contributes data, generated in two independent samples of ASD families, that suggests for the first time a role for the innate cytokine, macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), in the etiology of ASD.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by grants from the Cure Autism Now Foundation (EG), NIH grants NICHD–HD03008 and NICHD–HP35482 (FV, EG, GA), and AI042310 and AR049610 (RB), and the Korczak Foundation for Autism Research (GA, EM, AdB, RM). We express our gratitude to Prof. David Ward for encouraging our interest in this area, to Mr. Luke Turechek for his help with genotyping, and to Ms. Robyn Rissman for her editorial assistance. We are also indebted to the study participants and their families.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial or other conflicts requiring disclosure.

References

- 1.Trentacoste SV, Rapin I. The genetics of autism. Pediatrics. 2004;13:e472–486. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.e472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeargin-Allsopp M, Rice C, Karapurkar T, Doernberg N, Boyle C, Murphy C. Prevalence of autism in a US metropolitan area. JAMA. 2003;289:49–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sung YJ, Dawson G, Munson J, Estes A, Schellenberg GD, Wijsman EM. Genetic investigation of quantitative traits related to autism: use of multivariate polygenic models with ascertainment adjustment. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2005;76:68–81. doi: 10.1086/426951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trikalinos TA, Karvouni A, Zintzaras E, et al. A heterogeneity-based genome search meta-analysis for autism-spectrum disorders. Molecular Psychiatry. 2006;11:29–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Autism Genome Project (AGP) Consortium. Mapping autism risk loci using genetic linkage and chromosomal rearrangements. Nature Genetics. doi: 10.1038/ng1985. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Molecular Genetic Study of Autism Consortium. A full genome screen for autism with evidence for linkage to a region on chromosome 7q. Human Molecular Genetics. 1998;7:571–578. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.3.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schellenberg GD, Dawson G, Sung YJ, et al. Evidence for multiple loci from a genome scan of autism kindreds. Molecular Psychiatry. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001874. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gharani N, Benayed R, Mancuso V, Brzustowicz LM, Millonig JH. Association of the homeobox transcription factor, ENGRAILED 2, 3, with autism spectrum disorder. Molecular Psychiatry. 2004;9:474–484. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell D, Sutcliffe J, Ebert P, et al. A genetic variant that disrupts MET transcription is associated with autism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:16834–16839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605296103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Gent T, Heijnen CJ, Treffers PD. Autism and the immune system. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 1997;38:337–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Money J, Bobrow NA, Clarke FC. Autism and autoimmune disease: a family study. Journal of Autism & Childhood Schizophrenia. 1971;1:146–160. doi: 10.1007/BF01537954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Comi AM, Zimmerman AW, Frye VH, Law PA, Peeden JN. Familial clustering of autoimmune disorders and evaluation of medical risk factors in autism. Journal of Child Neurology. 1999;14:388–394. doi: 10.1177/088307389901400608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sweeten TL, Bowyer SL, Posey DJ, Halberstadt GM, McDougle CJ. Increased prevalence of familial autoimmunity in probands with pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e420. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.5.e420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connolly AM, Chez MG, Pestronk A, Arnold ST, Mehta S, Deuel RK. Serum autoantibodies to brain in Landau-Kleffner variant, autism, and other neurologic disorders. Journal of Pediatrics. 1999;134:607–613. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70248-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh VK, Rivas WH. Prevalence of serum antibodies to caudate nucleus in autistic children. Neuroscience Letters. 2004;355:53–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh VK, Warren RP, Odell JD, Warren WL, Cole P. Antibodies to myelin basic protein in children with autistic behavior. Brain, Behavior, & Immunity. 1993;7:97–103. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1993.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vargas DL, Nascimbene C, Krishnan C, Zimmerman AW, Pardo CA. Neuroglial activation and neuroinflammation in the brain of patients with autism. Annals of Neurology. 2005;57:67–81. doi: 10.1002/ana.20315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ashwood P, Van de Water J. Is autism an autoimmune disease? Autoimmunity Reviews. 2004;3:557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashwood P, Van de Water J. A review of autism and the immune response. Clinical & Developmental Immunology. 2004;11:165–174. doi: 10.1080/10446670410001722096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalton P, Deacon R, Blamire A, et al. Maternal neuronal antibodies associated with autism and a language disorder. Annals of Neurology. 2003;53:533–537. doi: 10.1002/ana.10557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herbert MR. Autism: a brain disorder or a disorder tha affects the brain? Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 2005;6:354–379. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stubbs EG, Crawford ML. Depressed lymphocyte responsiveness in autistic children. Journal of Autism & Childhood Schizophrenia. 1977;7:49–55. doi: 10.1007/BF01531114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warren RP, Margaretten NC, Pace NC, Foster A. Immune abnormalities in patients with autism. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 1986;16:189–197. doi: 10.1007/BF01531729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denney DR, Frei BW, Gaffney GR. Lymphocyte subsets and interleukin-2 receptors in autistic children. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 1996;26:87–97. doi: 10.1007/BF02276236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plioplys AV, Greaves A, Kazemi K, Silverman EK. Lymphocyte function in autism and Rett syndrome. Neuropsychobiology. 1994;29:12–16. doi: 10.1159/000119056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warren RP, Yonk J, Burger RW, Odell D, Warren WL. DR-positive T cells in autism: association with decreased plasma levels of the complement C4B protein. Neuropsychobiology. 1995;31:53–57. doi: 10.1159/000119172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hollander E, DelGiudice-Asch G, Simon L, et al. B lymphocyte antigen D8/17 and repetitive behaviors in autism. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:317–320. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crow MK, DelGiudice-Asch G, Zehetbauer JB, et al. Autoantigen-specific T cell proliferation induced by the ribosomal P2 protein in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1994;94:345–352. doi: 10.1172/JCI117328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burgess NK, Sweeten TL, McMahon WM, Fujinami RS. Hyperserotoninemia and altered immunity in autism. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2006;36:697–704. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torres AR, Maciulis A, Stubbs EG, Cutler A, Odell D. The transmission disequilibrium test suggests that HLA-DR4 and DR13 are linked to autism spectrum disorder. Human Immunology. 2002;63:311–316. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(02)00374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warren RP, Singh VK, Cole P, et al. Possible association of the extended MHC haplotype B44-SC30-DR4 with autism. Immunogenetics. 1992;36:203–207. doi: 10.1007/BF00215048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogers T, Kalaydjieva L, Hallmayer J, et al. Exclusion of linkage to the HLA region in ninety multiplex sibships with autism. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 1999;29:195–201. doi: 10.1023/a:1023075904742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zimmerman AW, Jyonouchi H, Comi AM, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid and serum markers of inflammation in autism. Pediatric Neurology. 2005;33:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pardo CA, Vargas DL, Zimmerman AW. Immunity, neuroglia and neuroinflammation in autism. International Review of Psychiatry. 2005;17:485–495. doi: 10.1080/02646830500381930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calandra T, Roger T. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor: a regulator of innate immunity. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2003;3:791–800. doi: 10.1038/nri1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gregersen PK, Bucala R. MIF, MIF alleles, and the genetics of inflammatory disorders: Incorporating disease outcome into the definition of phenotype. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2003;48:1171–1176. doi: 10.1002/art.10880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baugh JA, Chitnis S, Donnelly SC, et al. A functional promoter polymorphism in the macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) gene associated with disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Genes & Immunity. 2002;3:170–176. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Benedetti F, Meazza C, Vivarelli M, et al. Functional and prognostic relevance of the −173 polymorphism of the macrophage migration inhibitory factor gene in systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2003;48:1398–1407. doi: 10.1002/art.10882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paul R, Augustyn A, Klin A, Volkmar FR. Perception and production of prosody by speakers with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2005;35:205–220. doi: 10.1007/s10803-004-1999-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mulder EJ, Anderson GM, Kema IP, et al. Serotonin transporter intron 2 polymorphism associated with rigid-compulsive behaviors in Dutch individuals with pervasive developmental disorder. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B, Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2005;133:93–96. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 1994;24:659–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lord C, Rutter M, Goode S, et al. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule: a standardized observation of communicative and social behavior. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 1989;19:185–212. doi: 10.1007/BF02211841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chanock SJ, Manolio T, et al. NCI-NHGRI Working Group on Replication in Association Studies. Replicating genotype-phenotype associations. Nature. 2007;447:655–660. doi: 10.1038/447655a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horvath S, Xu X, Laird NM. The family based association test method: strategies for studying general genotype--phenotype associations. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2001;9:301–306. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Steen K, Lange C. PBAT: a comprehensive software package for genome-wide association analysis of complex family-based studies. Human Genomics. 2005;2:67–69. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-2-1-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fisher RA. Statistical methods for research workers. New York, NY: Hafner; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Neale BM, Sham PC. The future of association studies: gene-based analysis and replication. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2004;75:353–362. doi: 10.1086/423901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rabinowitz D, Laird N. A unified approach to adjusting association tests for population admixture with arbitrary pedigree structure and arbitrary missing marker information. Human Heredity. 2000;50:211–223. doi: 10.1159/000022918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mizue Y, SG, Leng L, et al. Role for macrophage migration inhibitory factor in asthma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:14410–14415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507189102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mulder EJ, Anderson GM, Kema IP, et al. Platelet serotonin levels in pervasive developmental disorders and mental retardation: diagnostic group differences, within-group distribution, and behavioral correlates. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:491–499. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cohly HH, Panja A. Immunological findings in autism. International Review of Neurobiology. 2005;71:317–341. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(05)71013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu S-P, Leng L, Feng Z, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor promoter polymorphisms and the clinical expression of scleroderma. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2006;54:3661–3669. doi: 10.1002/art.22179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun CW, Li HW, Leng L, Raizada MK, Bucala R, Sumners C. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor: An intracellular inhibitor of angiotensin II-induced increases in neuronal activity. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:9944–9952. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2856-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lolis E, Bucala R. Therapeutic approaches to innate immunity. Nature Review Drug Discovery. 2003;2:635–645. doi: 10.1038/nrd1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bucala R, Lolis E. MIF: A critical component of autoimmune inflammatory diseases. Drug News Perspect. 2004;18:417–426. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2005.18.7.939345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Happe F, Ronald A, Plomin R. Time to give up on a single explanation for autism. Nature Neuroscience. 2006;9:1218–1220. doi: 10.1038/nn1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]