Abstract

The pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC), required for complete glucose oxidation, is essential for brain development. Although PDC deficiency is associated with a severe clinical syndrome, little is known about its effects on either substrate oxidation or synthesis of key metabolites such as glutamate and glutamine. Computational simulations of brain metabolism indicated that a 25% reduction in flux through PDC and a corresponding increase in flux from an alternative source of acetyl-CoA would substantially alter the 13C NMR spectrum obtained from brain tissue. Therefore, we evaluated metabolism of [1,6-13C2]glucose (oxidized by both neurons and glia) and [1,2-13C2]acetate (an energy source that bypasses PDC) in the cerebral cortex of adult mice mildly and selectively deficient in brain PDC activity, a viable model that recapitulates the human disorder. Intravenous infusions were performed in conscious mice and extracts of brain tissue were studied by 13C NMR. We hypothesized that mice deficient in PDC must increase the proportion of energy derived from acetate metabolism in the brain. Unexpectedly, the distribution of 13C in glutamate and glutamine, a measure of the relative flux of acetate and glucose into the citric acid cycle, was not altered. The 13C labeling pattern in glutamate differed significantly from glutamine, indicating preferential oxidation of [1,2-13C]acetate relative to [1,6-13C]glucose by a readily discernible metabolic domain of the brain of both normal and mutant mice, presumably glia. These findings illustrate that metabolic compartmentation is preserved in the PDC-deficient cerebral cortex, probably reflecting intact neuron-glia metabolic interactions, and that a reduction in brain PDC activity sufficient to induce cerebral dysgenesis during development does not appreciably disrupt energy metabolism in the mature brain.

INTRODUCTION

Glucose metabolism provides most of the energetic demands of the adult mammalian brain (Clark DD, 1999). The complete aerobic oxidation of glucose requires the sequential action of glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. The mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) is fundamental for this process: PDC links glycolysis with the TCA cycle by catalyzing the oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate to acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) (Patel and Korotchkina, 2006; Pithukpakorn, 2005). In the brain, PDC is expressed by neurons and, to a lesser degree, by glia, but uncertainty exists about the extent and magnitude of metabolic impact of PDC deficiency in vivo. Nevertheless, reductions in PDC activity, as typically observed in tissues obtained from PDC-deficient patients, can be presumed to limit acetyl-CoA production from glucose in both major brain cell types (neurons and glia) (Pliss et al., 2007), which may then secondarily impact closely related and regulated metabolic activities, such as the TCA cycle and anaplerosis. This hypothesis, however, has not been evaluated in PDC-deficient neural tissue in situ.

Addressing these questions is also relevant because PDC deficiency is an important cause of disability associated with lactic acidosis in man (Pithukpakorn, 2005; Robinson, 2006). Human PDC deficiency encompasses a broad clinical spectrum that preferentially impacts the nervous system, ranging from minimal neurological impairment (such as mild intermittent movement incoordination or ataxia) to severe neurobehavioral disability or even neonatal or infantile death (Robinson, 2006; Robinson et al., 1996). Brain structural abnormalities are prominent, affecting neurons in the gray matter (manifested as neuronal migration defects in the cerebral cortex) and myelin structure in the white matter (ranging from hypoplasia to absence of myelinated tracts such as the corpus callosum of the cerebral hemispheres) (Brown et al., 1994; Chow et al., 1987; Michotte et al., 1993; Pliss et al., 2007; Pliss et al., 2004). Therapies have focused on metabolic interventions intended to enhance acetyl-CoA synthesis, such as the induction of hepatic ketone body production using high-fat ketogenic diets (Pithukpakorn, 2005). Ketone bodies can be readily taken up and oxidized by the brain and converted to acetyl-CoA, bypassing PDC and –presumably- restoring this deficient TCA cycle precursor (Brown et al., 1994; Pithukpakorn, 2005; Wexler et al., 1997). This therapeutic principle constitutes another argument in support of potential TCA cycle impairment in PDC deficiency.

As previously reported by us (Pliss et al., 2004), PDC-deficient mice exhibit a ~ 25% reduction of PDC activity in the brain. A reduction of this magnitude can cause clinical manifestations typical of PDC deficiency in man when assayed in fibroblasts or skeletal muscle samples (Quintana et al., 2010; Robinson et al., 1996; Shevell et al., 1994), and manifest cerebral malformations similar to those harbored by PDC-deficient patients (Johnson et al., 2001; Pliss et al., 2007; Pliss et al., 2004). More severe reductions in PDC activity are almost invariably lethal.

In the present work, we have characterized the metabolism of intravenously infused [1,2-13C2]acetate and [1,6-13C2]glucose in the cerebral cortex of conscious mice rendered selectively deficient in brain PDC using 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Oxidation of glucose in either glia or neurons requires PDC. Consequently, a modest, controlled reduction in PDC activity would be expected to reduce the ratio of glucose oxidation relative to acetate oxidation and thereby change the distribution of 13C in both glutamine and glutamate. Further, since both the oxidation of acetate and the production of glutamine are thought to occur preferentially in glia, and since PDC deficiency predominantly interferes with neuronal development, a differential effect of PDC deficiency on 13C labeling in glutamate compared to glutamine would be anticipated. Surprisingly, the 13C labeling in glutamate and glutamine was not altered in PDC deficiency. In addition, the 13C labeling pattern of glutamate and glutamine differed significantly from each other in both control and PDC-deficient animals, suggesting that both infused substrates were differentially oxidized in neurons and glia, and that exchange of both molecules across the two compartments was incomplete, as previously identified in man and other model organisms. The findings demonstrate that a ~25% reduction of total PDC activity in the adult brain does not significantly alter the activity of major metabolic pathways or disrupt the metabolic compartmentation of the cerebral cortex, suggesting that the clinical manifestations of PDC deficiency are most likely caused by mechanisms stemming from the increased demand for acetyl-CoA for biosynthesis of brain lipids and cell proliferation experienced during development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal preparation

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of UT Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas and the State University of New York at Buffalo. All institutional regulations for animal acquisition and care by UT Southwestern were followed. The generation and neuropathological characteristics of the mice deficient in brain PDC used here were previously described (Pliss et al., 2007; Pliss et al., 2004). Animal breeding for the generation of PDC-deficient and control female mice and their genotype identification were also performed as described (Pliss et al., 2004). Briefly, female mice carrying the Pdha1flox8 alleles (consisting of two loxP sites inserted into intronic sequences flanking exon 8) were bred with males from the transgenic line B6.Cg[SJL]-TgN[NesCre]1Kln (Crebr). On postnatal day 10 progeny tails were clipped for DNA isolation (OmniPrep kit, BioWorld, Dublin, OH) and genotyped using PCR with primers specific for the Cre transgene and floxed portion of the Pdha1 as previously described (Pliss et al., 2004). Animals carrying floxed Pdha1 allele in a combination with Crebr+ was identified PDC-deficient, while their littermates (control) with Crebr− were not. We have previously reported that these animals manifest about a 25% reduction in both active and total PDC activity in the brains of adult PDC-deficient females (Pliss et al., 2007; Pliss et al., 2004). Therefore, we studied adult female PDC-deficient (n=4, weight (g) (mean and standard error of the mean hereafter): 32.17 ± 2.80) and normal littermates (n=3, weight (g): 30.90 ± 2.03) (age range: 12–14 months).

13C-labeled substrate infusion

The right jugular vein was aseptically cannulated under intraperitoneally-administered anesthesia that included ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Following recovery from anesthesia, mice were individually housed under standard animal care conditions with ad libitum access to water and food. Seven days post-cannulation, the mice were habituated and then confined to a Lucite cage designed to prevent ambulation. [1,6 13C2]-glucose (1-13C, 99% enriched; 6-13C, 97% enriched) and [1,2 13C2]-acetate (1-13C, 99% enriched; 6-13C, 99% enriched, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Cambridge, MA) were co-administered as a bolus of 0.2 mg/g of body weight for each tracer (in 0.2 ml of saline) infused over 1 min, followed by a continuous infusion of 0.006 mg/g of body weight/min for each tracer (in 0.375 ml of saline) at 150 μl/hr during 150 min to assure isotopic steady state (data not shown). The pH of all infused solutions was adjusted to 7.4. Animals were decapitated at the end of the infusion and the brains rapidly removed (<15 s) followed by manual separation of the cerebral cortex, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -85°C until processing for NMR analysis.

Preparation of brain extracts

Frozen cortices were finely grounded in a mortar under liquid nitrogen. 4% perchloric acid was added to each sample (1:4 w/v) followed by centrifugation at 47800 g for 15 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube where chloroform/tri-n-octylamine (78% / 22%; v/v) was added in 1:2 volumetric ratio of solvent: supernatant, increasing the pH to 6.0. The samples were centrifuged at 3300 g for 15 min, and the aqueous phase removed and transferred to a microfuge tube for lyophilization. 200 μl of deuterium oxide (99.96%, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories) was added to each sample and the pH adjusted to 7.0 with 2-3 μL of 1 M of sodium deuteroxide (99.5%, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories). The extracts were then centrifuged at 18,400 g for 1 min and the supernatant removed and placed into a 3-mm NMR tube for subsequent analysis.

Carbon NMR spectroscopy

Proton-decoupled 13C spectra were acquired on a 600 MHz Oxford magnet and Varian VNMRS Direct Drive console using a 3 mm broadband probe (Varian, Palo Alto, CA). Proton decoupling was performed at 2.3 kHz using a Waltz-16 sequence. 13C NMR spectroscopy parameters included a 45° flip angle per transient, a relaxation delay of 1.5 s, an acquisition time of 1.5 s, and a spectral width of 36.7 kHz. Samples were spun at 20 Hz and 25°C. A heteronuclear 2H lock was used to compensate for magnet drift during data acquisition. To achieve adequate signal-to-noise of cortex spectra, the number of scans acquired were typically 12,000 to 15,000.

Analysis of spectra

NMR spectral analyses were performed with ACD/Spec Manager 11.0 software (Advanced Chemistry Development, Inc., Toronto ON, Canada). Time-series free induction decays were zero-filled and windowed with an exponential weighting function prior to Fourier transformation for analysis of spectral contents. Metabolite peaks were then identified based on chemical shift position referenced to the glutamate C4 singlet resonance located at 34.2 ppm, which concurs with previous assignments (Gruetter et al., 2001; Pardo et al., 2011). Each peak was then fitted with a Gauss-Lorentz function and the area measurements for each fitted resonance peak and their multiplets estimated. The fractional amount of multiplets for each isotopomer was calculated by dividing the estimated area of each multiplet relative to the total spectral area of the isotopomer (for example, the area of the quartets generated by glutamate C4 relative to the total spectral area arising from glutamate C4). The relative contribution of the metabolism of glucose, acetate and unlabeled sources to the NMR spectra was estimated based on the fraction of multiplets of TCA cycle-derived isotopomers (i.e., glutamate, glutamine and GABA) in all carbon positions.

13C simulation study

To determine potential changes of the glutamate C4 spectrum as a result of PDC deficiency, several simulation studies were carried out using TCAsim software (http://www4.utsouthwestern.edu/rogersnmr/software/index.html). The simulations were performed in a single cell compartment assuming that the enrichments of glucose-derived [2-13C]acetyl-CoA and acetate-derived [1,2-13C2]acetyl-CoA were 50% and 100%, respectively, as labeled glucose-derived acetyl-CoA enrichment is far smaller than 100% under similar experimental conditions (Marin-Valencia et al., 2012). Under physiological conditions, flux through PDC was considered 80% of the total TCA cycle flux. Under a 25% reduction of PDC activity, PDC rate was 60% of the total TCA cycle flux.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed with a two-sample Student’s t-test not assuming equal variances using SPSS Graduate Pack version 18.0 (SPSS; Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Expected 13C labeling

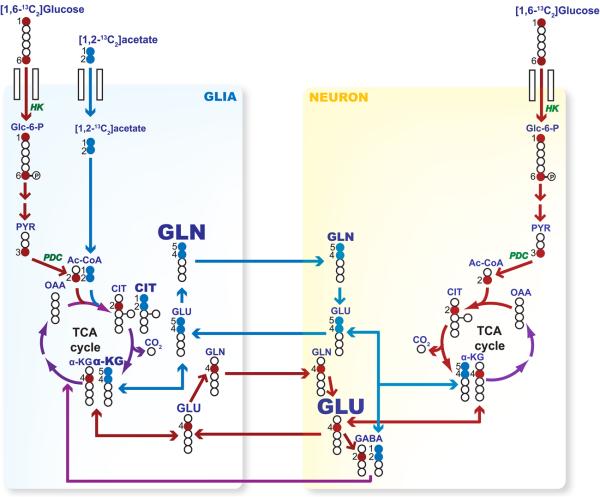

Results from the simulation studies illustrate marked differences in the glutamate C4 labeling pattern between the normal and PDC-deficient state (Figure 1). As expected, the contribution of [1,2-13C2]acetate to the glutamate C4 spectrum was considerably larger in PDC deficiency relative to normal as depicted by the prominent doublet D45 and quartet. Under normal PDC activity, the glutamate C4 spectrum is dominated by the singlet and doublet D34, which are multiplets primarily derived from [1,6-13C2]glucose. However, these simulations were performed assuming a single metabolic compartment. Figure 2 depicts the known 13C labeling mechanisms present in two brain compartments (labeled as neurons and glia) when both [1,2-13C2]acetate and [1,6-13C2]glucose are simultaneously available. Assuming that acetate is mainly or exclusively metabolized in glia (Cerdan et al., 1990; Minchin and Beart, 1975; Waniewski and Martin, 1998), glial glutamine and glutamate generated from [1,2-13C2]acetate will be labeled in carbon positions 4 and 5 during the first cycle (“turn”) of the TCA cycle, appearing as a doublet (D45) in the 13C NMR spectrum arising from scalar coupling, in conjunction with additional labeling in positions 3, 4 and 5 in subsequent turns of the cycle, manifested as quartets of resonances (Q). Conversely, and although glucose is taken up by both major cell types, it is predominantly metabolized in neurons because neuronal TCA cycle flux exceeds glial TCA cycle flux (Cruz and Cerdan, 1999; Gruetter et al., 2001; Oz et al., 2004; Sibson et al., 2001). Additionally, metabolism of [1,6-13C2]glucose generates glutamate and glutamine labeled in carbon 4 in the first turn of the TCA cycle, appearing as singlets (S) in the 13C spectrum, in addition to labeling observable in carbons 3 and 4 during the second and subsequent turns through the cycle, which is represented as the doublet D34.

Figure 1.

Expected glutamate C4 spectra from simulation studies under physiological (A) and PDC-deficient conditions (B). The simulations were enclosed in a single cell compartment assuming that the enrichments of glucose-derived [2-13C]acetyl-CoA and acetate-derived [1,2-13C2]acetyl-CoA were 50% and 100%, respectively. PDC activity was considered normal when its flux was 80% of the total TCA cycle flux and deficient (in 25%) when its rate was 60% of the total TCA cycle flux. S: singlet, Dxx: doublet, Q: quartet.

Figure 2.

Schematic metabolic diagram depicting the 13C-label distribution during the first cycle (“turn”) of the TCA cycle in brain cells when [1,2-13C2]acetate and [1,6-13C2]glucose are simultaneously administered. [1,2-13C2]acetate is exclusively metabolized in glial cells, giving rise to glutamine and, to a lesser extent, to glutamate labeled in carbon positions 4 and 5, whereas glucose can be metabolized in both cell types (neurons and glia) leading to the synthesis of both glutamate (which is primarily produced in neurons) and glutamine labeled in carbon 4. Pyruvate carboxylase (not illustrated) is exclusively present in glia. In red: glucose-derived 13C; in blue: acetate-derived 13C; in purple when red and blue converge. Glc-6-P: glucose 6-phosphate, HK: hexokinase, PYR: pyruvate, PDC: pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, Ac-CoA: acetyl-CoA, CIT: citrate, α-KG: α-ketoglutarate.

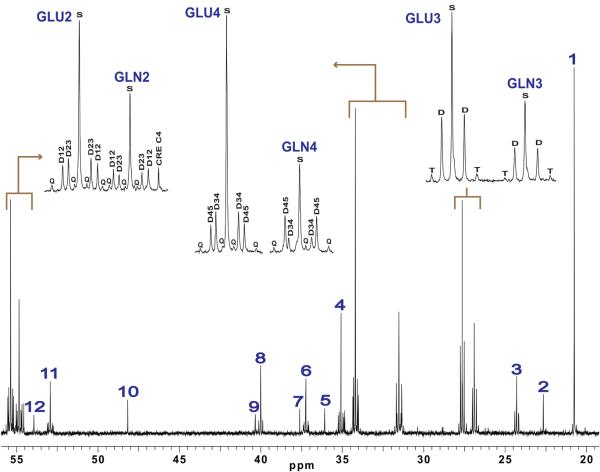

Cortical spectra

13C spectra arising from cerebral cortex samples were well resolved with favorable signal-to-noise ratios that lent themselves to analysis and computation. Figures 3 and 4 illustrate representative 13C-NMR spectra of cortex extracts from both PDC-deficient and normal mice co-infused with [1,2-13C2]acetate and [1,6-13C2]glucose, respectively. Resonances assigned to glutamate, glutamine, GABA, aspartate, N-acetyl-aspartate and lactate were readily identified in all spectra. In both groups of animals, glutamate, glutamine and lactate gave rise to the largest resonances identified. This is consistent with the notion that glucose and acetate utilization in the cortex preferentially leads to the production of glutamate and glutamine, and with the high glycolytic potential of brain cells that enables them to produce lactate from glucose (Escartin et al., 2006; Hassel et al., 1995; Sonnewald et al., 1994; Tansey et al., 1991).

Figure 3.

A segment of a representative cortical 13C spectrum from a PDC-deficient mouse co-infused with [1,2-13C2]acetate and [1,6-13C2]glucose exhibiting the key metabolites of interest. The insets display the labeling patterns of glutamate and glutamine in carbons 2, 3 and 4. 1: Lactate C3, 2: N-acetylaspartate C6, 3: GABA C3, 4: GABA C2, 5: Taurine C2, 6: Aspartate C2, 7: Creatine C2, 8: GABA C4, 9: N-acetylaspartate C3, 10: taurine C1, 11: Aspartate C2, 12: N-acetylaspartate C2. C#: carbon labeled in position #. Sx: singlet, Dxx: doublet, T: triplet, Q: quartet.

Figure 4.

Detail of a cortical 13C spectrum obtained from a normal mouse co-infused with [1,2-13C2]acetate and [1,6-13C2]glucose. The insets display the labeling patterns of glutamate and glutamine in carbons 2, 3 and 4. 1: Lactate C3, 2: N-acetylaspartate C6, 3: GABA C3, 4: GABA C2, 5: Taurine C2, 6: Aspartate C2, 7: Creatine C2, 8: GABA C4, 9: N-acetylaspartate C3, 10: taurine C1, 11: Aspartate C2, 12: N-acetylaspartate C2. C#: carbon labeled in position #. Sx: singlet, Dxx: doublet, T: triplet, Q: quartet.

13C multiplets resulting from 13C-13C coupling were also well resolved in all NMR spectra (Figures 3 and 4). The presence of isotopomer multiplets demonstrates that, in both groups of animals, glucose and acetate were oxidized via the TCA cycle. No differences in the abundance of 13C multiplets in glutamate, glutamine and GABA were detected between animal groups (Table 1), which suggests that the activity of the TCA cycle was not impaired in the mutant relative to the normal mouse.

Table 1.

Fractional amounts of the multiplets of glutamate (GLU) and glutamine (GLN) C4 and GABA C2 detected in the cortex of PDC-deficient (n=4) and normal mice (n=3) (expressed as mean ± SEM). The fractional amount was calculated from the area of each individual multiplet divided by the total area of the isotopomer. The infusion protocol and brain metabolic pathways lead to the absence measurable labeling in the multiplets left blank in the Table. No significant differences were detected between animal groups. Within each group, the enrichment of multiplets was equivalent for glutamate C4 and GABA C2, and both were significantly different from glutamine multiplet enrichment (* and ** mark differences between glutamate and glutamine or between GABA and glutamine, as glutamate and GABA are expected to display a similar labeling pattern). *P ≤0.05, **P ≤0.01. S: singlet, Dxx: doublet, Q: quartet, N.D.: not detected.

| PDC-deficient mice |

| 13C MULTIPLETS | GLU C4 | GLN C4 | GABA C2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| S | 0.637 ± 0.023* | 0.443 ± 0.053 | 0.635 ± 0.027* |

| D34 | 0.195 ± 0.017** | 0.105 ± 0.012 | - |

| D45 | 0.136 ± 0.013** | 0.379 ± 0.045 | - |

| D23 | - | - | 0.183 ± 0.012 |

| D12 | - | - | 0.133 ± 0.008** |

| Q | 0.027 ± 0.004 | 0.072 ± 0.017 | N.D. |

| Control mice |

| 13C MULTIPLETS | GLU C4 | GLN C4 | GABA C2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| S | 0.699 ± 0.022** | 0.513 ± 0.020 | 0.636 ± 0.027* |

| D34 | 0.158 ± 0.017* | 0.082 ± 0.012 | - |

| D45 | 0.122 ± 0.003** | 0.360 ± 0.024 | - |

| D23 | - | - | 0.158 ± 0.010** |

| D12 | - | - | 0.137 ± 0.020** |

| Q | 0.02 ± 0.005* | 0.043 ± 0.006 | N.D. |

Multiplet 13C NMR investigated the effect of reduced brain pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDC) activity

The work represents the first report of 13C glucose/acetate brain metabolism in the conscious mouse

Brain metabolic compartmentation, demonstrated in other species by other approaches, was found

Importanty, compartmentalized metabolism and tricarboxylic acid cycle flux remained unaltered

Thus, the manifestations of PDC deficiency are not due to major alteration of metabolism in the adult

Overall, there were no significant differences in the 13C-multiplet pattern (Figure 3 and 4) and the fractional amount of multiplets (Table 1) of glutamate, glutamine and GABA (data not shown) between PDC-deficient and control animals. Within each group, the 13C-multiplet spectra of glutamate and GABA were very similar as illustrated by the fractional amount of multiplets (Table 1), in agreement with the contention that the GABA pool derives directly from the glutamate pool (Cerdan et al., 1990). The 13C-multiplets pattern of glutamate and glutamine, however, differed significantly (Figures 3 and 4 and Table 1). In the case of the C4 resonance, glutamine C4 exhibited a large signal arising from the doublet D45 relative to the singlet and the doublet D34, indicating that a significant fraction of glutamine arose from [1,2-13C2]acetate. In contrast, the glutamate C4 resonance was dominated by the singlet and the doublet D34, suggesting that most of the glutamate was produced from [1,6-13C2]glucose in the neuronal compartment. These findings can also be explained by postulating the presence of a slowly-exchangeable pool of molecules. For example, in glutamine C4, the D45/D34 ratio far exceeded unity (no differences were detected between mice groups: PDC-deficient: 3.853 ± 0.867, normal: 4.676 ± 1.078), whereas in glutamate C4, it was closer to unity (no differences were detected: PDC-deficient: 0.722 ± 0.101, normal: 0.791 ± 0.084).

DISCUSSION

We have analyzed cortical metabolism of ketogenic and glucogenic brain energetic substrates in tissue obtained from conscious PDC-deficient adult female mice using NMR multiplet data. Our main goal was to investigate the metabolism of [1,2-13C2]acetate relative to [1,6-13C2]glucose in the cerebral cortex and to determine whether the utilization and metabolism of these substrates was impaired under a limited (25%), controlled degree of PDC activity reduction relevant to neural function and neurological disease. The results indicate that: 1) the relative rates of oxidation of acetate and glucose were not significantly changed in the cortex of the mutant brain relative to the normal mouse; 2) substrate oxidation compartmentation within and across brain cells was preserved in both animal groups; and 3) there were exchangeable and slowly-exchangeable (i.e., undetectably exchangeable under our experimental conditions) glutamate pools in the cerebral cortex.

Preservation of metabolic compartmentation

13C multiplets of all glucose and acetate-derived isotopomers were resolved ex vivo for the first time after metabolism by the conscious mouse cortex (Figures 3, 4, and 5). These observations are relevant because, as described in the heart (Jeffrey et al., 1999), multiplets potentially provide potentially useful information for the computation of flux rates of metabolic pathways. In agreement with in vivo and in vitro studies (Deelchand et al., 2009; Haberg et al., 1998; Hassel et al., 1997; Taylor et al., 1996), the co-infusion of [1,2-13C2]acetate and [1,6-13C2]glucose revealed a distinct labeling pattern in glutamate and glutamine (Figure 5). This finding most likely results from preserved compartmentalized substrate oxidation and from an incomplete transit of isotopomers between brain cells (neurons and glia). If glutamate and glutamine were rapidly exchanged, their labeling pattern should be identical under isotopic steady-state conditions (separately determined to occur at 150 min for glucose under our infusion conditions, Marin-Valencia et al., 2012). This is probably the case, for example, for GABA and glutamate, whose labeling patterns were equivalent (Table 1) suggesting that the GABA pool directly communicates with the glutamate pool.

Figure 5.

Labeling pattern of glutamate and glutamine C4 in the cortex of PDC-deficient (A) and normal (B) mice infused with [1,6-13C2]glucose and [1,2-13C2]acetate, a representative 13C NMR spectra (separately obtained for comparative purposes) from the cortex of a normal mouse infused with [1,6-13C2]glucose (C) and from the forebrain of a normal mouse infused with [1,2-13C2]acetate (D). The labeling pattern of both C4 isotopomers is very similar when only 13C-glucose is administered, probably demonstrating that glucose is metabolized both by neurons and glia without indication of compartmentation. As 13C-acetate is infused alone or together with 13C-glucose, the labeling pattern of glutamate C4 and glutamine C4 differs significantly supporting the notion that acetate and glucose are oxidized differently in each cell compartment, and that there is a pool of these metabolites that is not rapidly exchangeable across both major cell types. C#: carbon labeled in position #. Sx: singlet, Dxx: doublet, T: triplet, Q: quartet.

Cerebral glutamate metabolism

Regarding the C4 resonance (Figure 5 and Table 1), the principal difference between glutamate and glutamine was the central singlet and the doublet D34, which was larger in glutamate relative to glutamine. In agreement with a previous study using [1,2-13C2]acetate (Cerdan et al., 1990), the results from our work suggest that there are at least three potential glutamate pools: 1) a glial pool, responsible for the doublet D45 and quartets in glutamate and glutamine, both resulting from [1,2-13C2]acetate oxidation in glia, 2) an exchangeable neuronal pool, mostly deriving from glial glutamine, and 3) a slowly exchangeable (with the exchange process remaining undetected by our methods) neuronal pool, mainly produced from glucose oxidation in the neuronal TCA cycle (a proposed model is illustrated in Figure 6). This “slowly-exchangeable” pool accounts for the singlet and the doublet D34 in glutamate and contributes discreetly to the small abundance of these multiplets in glutamine. An alternative pathway that potentially feeds the slowly-exchangeable pool of glutamate is the recycling of pyruvate, which originates from glial glutamine oxidized in the neuronal TCA cycle under the infusion of these 13C tracers (Cerdan et al., 1990) (Figure 7). In our experiments, pyruvate recycling would have manifested as a specific glutamate C4 labeling pattern, resulting in a relative increase of the singlet resonance compared with the quartet resonance. This was not observed.

Figure 6.

Diagram of [1,2-13C2]acetate and [1,6-13C2]glucose metabolism in glia and neurons as decteted by 13C-NMR spectroscopy from cortex extracts. At least two potential pools of brain glutamate are observed when both 13C-labeled substrates are infused: 1) an exchangeable glutamate pool, mostly originating from glial, acetate-derived glutamine, and 2) a slowly exchangeable pool of neuronal glutamate, principally produced by glucose oxidation in the neuronal TCA cycle. The GABA labeling pattern matches that of glutamate, suggesting that it directly communicates with the exchangeable and slowly-exchangeable pools of glutamate. The metabolism of [1,2-13C2]acetate also allowed for detection of alternative pathways that may contribute to the different labeling pattern of glutamate and glutamine, such as the recycling of pyruvate which, under these experimental conditions, originates primarily from glial glutamine oxidized in the neuronal compartment. These metabolic aspects are preserved in PDC-deficient mice. In red: glucose-derived 13C; in blue: acetate-derived 13C; in purple when red and blue converge. Glc-6-P: glucose 6-phosphate, HK: hexokinase, PYR: pyruvate, PDC: pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, Ac-CoA: acetyl-CoA, CIT: citrate, α-KG: α-ketoglutarate., OAA: oxaloacetate, MAL: malate.

The cerebral cortical TCA cycle

The presence of NMR multiplets in cortex extracts demonstrates that glucose and acetate were oxidized in the TCA cycle. However, the source of substrate for cortical oxidative metabolism in PDC-deficient mice is not clear. As previously reported (Pliss et al., 2004), PDC-deficient animals manifest approximately a 25% reduction of total PDC activity, a clinically significant decrease considering that PDC-deficient mice developed structural cerebral malformations (Pliss et al., 2004, Pliss et al., 2007) similar to those reported in the brains of PDC-deficient patients (Quintana et al., 2010; Robinson et al., 1996; Shevell et al., 1994). We reported previously that cells expressing wild-type PDC neither exhibited increased protein expression nor an increased proportion of active PDC activity in the dephosphorylated state (Pliss et al., 2004). Our results did not reveal differences in 13C spectral pattern and fractional amount of multiplets of glutamate, glutamine and GABA between PDC-deficient mice and controls, which suggests that a 25% reduction of total PDC activity in mature brain does not limit the TCA cycle activity. This disease state differs from other pathological states that secondarily impair PDC activity such as cerebral ischemia or traumatic brain injury (Richards et al., 2007; Richards et al., 2006; Robertson et al., 2007), which are associated with global mitochondrial dysfunction and diminished PDC activity (ranging from 33 to 50% of total activity (Cardell et al., 1989; Richards et al., 2007; Richards et al., 2006), in addition to other defects in the TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation.

Limitations

The principal limitation of the current study is the small number of animals examined. This constraint was imposed by the difficulty of generating PDC-deficient mice. Consequently the study is not powered sufficiently to discern small differences in the 13C NMR spectra between the two groups. However, the data illustrate that the magnitude of changes in the 13C spectrum predicted by simulations was not observed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study illustrates, for the first time, the analysis of 13C multiplets in the cortex of conscious mice applied to the evaluation of metabolism in PDC deficiency. The simultaneous infusion of [1,2-13C2]acetate and [1,6-13C2]glucose in normal mice revealed different labeling patterns between glutamate and glutamine consistent with brain compartmentation of substrate oxidation (as identified in other vertebrates) and with the presence of exchangeable and slowly-exchangeable pools of neuronal glutamate, features that were preserved in PDC-deficient mice. Furthermore, TCA cycle activity and anaplerosis were preserved in the cortex of mutant mice. These results reveal that pathologically-relevant defects in PDC do not extensively alter metabolic compartmentation or the function of major pathways in the mature cerebral cortex. It is possible that demand for acetyl-CoA for biosynthetic pathways (largely devoted to lipid synthesis) and oxidative metabolism during rapid brain growth in pre- and early postnatal periods might have contributed to impaired neurogenesis due to reduction in oxidative metabolism. However, in adulthood, oxidative metabolism remains unaltered, perhaps due to a marked reduction in the demand for acetyl-CoA by brain biosynthetic processes. Further studies are necessary to elucidate potential mechanisms that induce PDC-deficient cells to migrate aberrantly during brain development. Specifically, it will be of interest to investigate glucose metabolism in PDC-deficient mice during the suckling period when the cerebral demand for acetyl-CoA is highest for the purpose of lipid biosynthesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of NS077015 (JMP, LBG), Fundación Caja Madrid (IMV) and NIH grants RR002584 (JMP, CRM) and EB000461 (CRM), DK20478 (MSP), F32NS065640 (LBG) and Dallas Women’s Foundation (Billingsley Fund) (JMP).

Abbreviations

- PDC

pyruvate dehydrogenase complex

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- TCA

tricarboxylic acid

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Blin M, Crusio WE, Hevor T, Cloix JF. Chronic inhibition of glutamine synthetase is not associated with impairment of learning and memory in mice. Brain Res Bull. 2002;57:11–15. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00631-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GK, Otero LJ, LeGris M, Brown RM. Pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency. J Med Genet. 1994;31:875–879. doi: 10.1136/jmg.31.11.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardell M, Koide T, Wieloch T. Pyruvate dehydrogenase activity in the rat cerebral cortex following cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1989;9:350–357. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1989.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerdan S, Kunnecke B, Seelig J. Cerebral metabolism of [1,2-13C2]acetate as detected by in vivo and in vitro 13C NMR. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:12916–12926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Aoki C, Mahadomrongkul V, Gruber CE, Wang GJ, Blitzblau R, Irwin N, Rosenberg PA. Expression of a variant form of the glutamate transporter GLT1 in neuronal cultures and in neurons and astrocytes in the rat brain. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2142–2152. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02142.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow CW, Anderson RM, Kenny GC. Neuropathology in cerebral lactic acidosis. Acta Neuropathol. 1987;74:393–396. doi: 10.1007/BF00687218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DD, S.L. Circulation and energy metabolism of the brain. In: Siegel GJ, A.B., Albers RW, Fisher SK, Uhler MD, editors. Basic neurochemistry. Molecular, cellular and medical aspects, Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia: 1999. pp. 637–670. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz F, Cerdan S. Quantitative 13C NMR studies of metabolic compartmentation in the adult mammalian brain. NMR Biomed. 1999;12:451–462. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199911)12:7<451::aid-nbm571>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danbolt NC. Glutamate uptake. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;65:1–105. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deelchand DK, Nelson C, Shestov AA, Ugurbil K, Henry PG. Simultaneous measurement of neuronal and glial metabolism in rat brain in vivo using co-infusion of [1,6-13C2]glucose and [1,2-13C2]acetate. J Magn Reson. 2009;196:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escartin C, Valette J, Lebon V, Bonvento G. Neuron-astrocyte interactions in the regulation of brain energy metabolism: a focus on NMR spectroscopy. J Neurochem. 2006;99:393–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruetter R, Seaquist ER, Ugurbil K. A mathematical model of compartmentalized neurotransmitter metabolism in the human brain. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;281:E100–112. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.1.E100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen V, Shupliakov O, Brodin L, Ottersen OP, Storm-Mathisen J. Quantification of excitatory amino acid uptake at intact glutamatergic synapses by immunocytochemistry of exogenous D-aspartate. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4417–4428. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04417.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberg A, Qu H, Haraldseth O, Unsgard G, Sonnewald U. In vivo injection of [1-13C]glucose and [1,2-13C]acetate combined with ex vivo 13C nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy: a novel approach to the study of middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:1223–1232. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199811000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa J, Obara T, Tanaka K, Tachibana M. High-density presynaptic transporters are required for glutamate removal from the first visual synapse. Neuron. 2006;50:63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassel B, Bachelard H, Jones P, Fonnum F, Sonnewald U. Trafficking of amino acids between neurons and glia in vivo. Effects of inhibition of glial metabolism by fluoroacetate. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:1230–1238. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199711000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassel B, Westergaard N, Schousboe A, Fonnum F. Metabolic differences between primary cultures of astrocytes and neurons from cerebellum and cerebral cortex. Effects of fluorocitrate. Neurochem Res. 1995;20:413–420. doi: 10.1007/BF00973096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey FM, Reshetov A, Storey CJ, Carvalho RA, Sherry AD, Malloy CR. Use of a single (13)C NMR resonance of glutamate for measuring oxygen consumption in tissue. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:E1111–1121. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.6.E1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MT, Mahmood S, Hyatt SL, Yang HS, Soloway PD, Hanson RW, Patel MS. Inactivation of the murine pyruvate dehydrogenase (Pdha1) gene and its effect on early embryonic development. Mol Genet Metab. 2001;74:293–302. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2001.3249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam K, Nicoll R. Excitatory synaptic transmission persists independently of the glutamate-glutamine cycle. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9192–9200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1198-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Valencia I, Roe CR, Pascual JM. Pyruvate carboxylase deficiency: mechanisms, mimics and anaplerosis. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;101:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson J, Darmon M, Conjard A, Chuhma N, Ropert N, Thoby-Brisson M, Foutz AS, Parrot S, Miller GM, Jorisch R, Polan J, Hamon M, Hen R, Rayport S. Mice lacking brain/kidney phosphate-activated glutaminase have impaired glutamatergic synaptic transmission, altered breathing, disorganized goal-directed behavior and die shortly after birth. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4660–4671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4241-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna MC. The glutamate-glutamine cycle is not stoichiometric: fates of glutamate in brain. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:3347–3358. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michotte A, De Meirleir L, Lissens W, Denis R, Wayenberg JL, Liebaers I, Brucher JM. Neuropathological findings of a patient with pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 alpha deficiency presenting as a cerebral lactic acidosis. Acta Neuropathol. 1993;85:674–678. doi: 10.1007/BF00334680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minchin MC, Beart PM. Compartmentation of amino acid metabolism in the rat dorsal root ganglion; a metabolic and autoradiographic study. Brain Res. 1975;83:437–449. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90835-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieoullon A, Canolle B, Masmejean F, Guillet B, Pisano P, Lortet S. The neuronal excitatory amino acid transporter EAAC1/EAAT3: does it represent a major actor at the brain excitatory synapse? J Neurochem. 2006;98:1007–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oz G, Berkich DA, Henry PG, Xu Y, LaNoue K, Hutson SM, Gruetter R. Neuroglial metabolism in the awake rat brain: CO2 fixation increases with brain activity. J Neurosci. 2004;24:11273–11279. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3564-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer MJ, Hull C, Vigh J, von Gersdorff H. Synaptic cleft acidification and modulation of short-term depression by exocytosed protons in retinal bipolar cells. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11332–11341. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-36-11332.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo B, Rodrigues TB, Contreras L, Garzon M, Llorente-Folch I, Kobayashi K, Saheki T, Cerdan S, Satrustegui J. Brain glutamine synthesis requires neuronal-born aspartate as amino donor for glial glutamate formation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:90–101. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel MS, Korotchkina LG. Regulation of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:217–222. doi: 10.1042/BST20060217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pithukpakorn M. Disorders of pyruvate metabolism and the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Mol Genet Metab. 2005;85:243–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliss L, Mazurchuk R, Spernyak JA, Patel MS. Brain MR imaging and proton MR spectroscopy in female mice with pyruvate dehydrogenase complex deficiency. Neurochem Res. 2007;32:645–654. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9295-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliss L, Pentney RJ, Johnson MT, Patel MS. Biochemical and structural brain alterations in female mice with cerebral pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency. J Neurochem. 2004;91:1082–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana E, Gort L, Busquets C, Navarro-Sastre A, Lissens W, Moliner S, Lluch M, Vilaseca MA, De Meirleir L, Ribes A, Briones P. Mutational study in the PDHA1 gene of 40 patients suspected of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex deficiency. Clin Genet. 2010;77:474–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards EM, Fiskum G, Rosenthal RE, Hopkins I, McKenna MC. Hyperoxic reperfusion after global ischemia decreases hippocampal energy metabolism. Stroke. 2007;38:1578–1584. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.473967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards EM, Rosenthal RE, Kristian T, Fiskum G. Postischemic hyperoxia reduces hippocampal pyruvate dehydrogenase activity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:1960–1970. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson CL, Saraswati M, Fiskum G. Mitochondrial dysfunction early after traumatic brain injury in immature rats. J Neurochem. 2007;101:1248–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson BH. Lactic acidemia and mitochondrial disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2006;89:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson BH, MacKay N, Chun K, Ling M. Disorders of pyruvate carboxylase and the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1996;19:452–462. doi: 10.1007/BF01799106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevell MI, Matthews PM, Scriver CR, Brown RM, Otero LJ, Legris M, Brown GK, Arnold DL. Cerebral dysgenesis and lactic acidemia: an MRI/MRS phenotype associated with pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency. Pediatr Neurol. 1994;11:224–229. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(94)90107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibson NR, Mason GF, Shen J, Cline GW, Herskovits AZ, Wall JE, Behar KL, Rothman DL, Shulman RG. In vivo (13)C NMR measurement of neurotransmitter glutamate cycling, anaplerosis and TCA cycle flux in rat brain during. J Neurochem. 2001;76:975–989. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnewald U, Muller TB, Westergaard N, Unsgard G, Petersen SB, Schousboe A. NMR spectroscopic study of cell cultures of astrocytes and neurons exposed to hypoxia: compartmentation of astrocyte metabolism. Neurochem Int. 1994;24:473–483. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(94)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tansey FA, Farooq M, Cammer W. Glutamine synthetase in oligodendrocytes and astrocytes: new biochemical and immunocytochemical evidence. J Neurochem. 1991;56:266–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A, McLean M, Morris P, Bachelard H. Approaches to studies on neuronal/glial relationships by 13C-MRS analysis. Dev Neurosci. 1996;18:434–442. doi: 10.1159/000111438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waniewski RA, Martin DL. Preferential utilization of acetate by astrocytes is attributable to transport. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5225–5233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05225.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler ID, Hemalatha SG, McConnell J, Buist NR, Dahl HH, Berry SA, Cederbaum SD, Patel MS, Kerr DS. Outcome of pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency treated with ketogenic diets. Studies in patients with identical mutations. Neurology. 1997;49:1655–1661. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.6.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler BS, Kapousta-Bruneau N, Arnold MJ, Green DG. Effects of inhibiting glutamine synthetase and blocking glutamate uptake on b-wave generation in the isolated rat retina. Vis Neurosci. 1999;16:345–353. doi: 10.1017/s095252389916214x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]