Abstract

Human aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C3 (AKR1C3) was initially identified as an enzyme in reducing 5α-dihydrotestosterone (5α-DHT) to 5α-androstane-3α, 17β-diol (3α-diol) and oxidizing 3α-diol to androsterone. It was subsequently demonstrated to possess ketosteroid reductase activity in metabolizing other steroids including estrogen and progesterone, 11-ketoprostaglandin reductase activity in metabolizing prostaglandins, and dihydrodiol dehydrogenase x (DDx) activity in metabolizing xenobiotics. AKR1C3 was demonstrated in sex hormone-dependent tissues including testis, breast, endometrium, and prostate; in sex hormone-independent tissues including kidney and urothelium. Our previous study described the expression of AKR1C3 in squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma but not in small cell carcinoma. In this report, we studied the expression of AKR1C3 in normal tissue, adenocarcinomas (43 cases) and neuroendocrine (NE) tumors (40 cases) arising from the aerodigestive tract and pancreas. We demonstrated wide expression of AKR1C3 in superficially located mucosal cells, but not in NE cells. AKR1C3-positive immunoreactivity was detected in 38 cases (88.4%) of adenocarcinoma, but only in 7 cases (17.5%) of NE tumors in all cases. All NE tumors arising from the pancreas and appendix and most tumors from the colon and lung were negative. The highest ratio of positive AKR1C3 in NE tumors was found in tumors arising from the small intestine (50%). These results raise the question of AKR1C3’s role in the biology of normal mucosal epithelia and tumors. In addition, AKR1C3 may be a useful adjunct marker for the exclusion of the NE phenotype in diagnostic pathology.

Keywords: Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C3 (AKR1C3), neuroendocrine tumors, adenocarcinomas, pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, lung, immunohistochemistry

Introduction

The aldo-keto reductases (AKRs) comprise of functionally diverse 15 gene families [1]. Members of the AKR superfamily are generally monomeric (37 kD), cytosolic, NAD (P) (H)-dependent oxidoreductases, and multifunctional in that they convert carbonyl groups to primary or secondary alcohols (www.med.upenn.eud/akr) [2]. Substrates of AKR superfamily members include steroids, prostaglandins (PGs), and lipid aldehydes as substrates [3]. Four human AKR1C isoforms have been cloned and characterized; they are known as AKR1C1 [20α (3α)-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD)] [4], AKR1C2 (type 3 3α-HSD) [5,6], AKR1C3 (type 2 3α/type 5 17β-HSD) [7,8], and AKR1C4 (type 1 3α-HSD) [6].

AKR1C3 was originally cloned from human prostate [8] and placental cDNA libraries [9]. Based on enzyme kinetics, AKR1C3 possesses 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD), 3β-HSD, 17β-HSD, and 11-ketoprostaglandin reductase activities, and catalyzes androgen, estrogen, progesterone, and prostaglandin (PG) metabolism [8,10-12]. As a result, AKR1C3 is capable of indirectly governing ligand access to various nuclear receptors, including androgen receptor (AR), estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) [13], and regulating trans-activation activities of these nuclear receptors through intracrine actions [13].

AKR1C3 expression has been detected in normal tissues including steroid hormone-dependent cells such as breast cells [14], endometrial cells [15], prostate cells [16], and Leydig cells [17], as well as hormone-independent cells such as urothelial epithelium [16] and epithelium of the renal tubules [18]. We and others also demonstrated that AKR1C3 is abnormally expressed in multiple malignant tumors including hormone-related cancers such as breast cancer [19], endometrial cancer [15,20], and prostate cancer [16,21-23], as well as non-hormone-related cancers such as myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS, refractory anemia) [24], non-small cell carcinoma of the lung [25,26], Wilms’ tumor [27], and brain tumor [28].

Neuroendocrine (NE) epithelial cells are widely distributed in the aerodigestive tract and have the unique capability of synthesizing and secreting neuropeptides and hormones. These NE cells are most commonly found in the stomach, small intestine, appendix, colon, pancreas and bronchial mucosa in the aerodigestive tract. These NE epithelial cells are believed to be the origin of neuroendocrine tumor and small cell carcinoma. In fact, NE tumor is one of the most common tumors of the appendix [29]. Small cell carcinoma of the lung is a common tumor and highly aggressive NE carcinoma. In contrast, well-differentiated NE tumor (also known as carcinoid) and moderately-differentiated NE tumor (also known as atypical carcinoid) are less commonly found in the lung and far less aggressive. Interestingly, these tumors tend to occur in younger patients.

Although the expression of AKR1C3 mRNA has been demonstrated in the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas [8,12], the topographical distribution in different cell types and tumors arising from these organs have never been described. This study focuses on the expression of AKR1C3 in normal epithelial cells, NE tumors, and carcinomas arising in the pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, and lung.

Materials and methods

Human normal and neoplastic tissue

A total of 83 separate cases of archival, formalin fixed, paraffin embedded biopsy or resection specimens were retrieved. All specimens were obtained through the Department of Pathology at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center with Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval. Cases were limited to those with indisputable diagnostic features, containing sufficient amount of tissues, and free of excessive cauterization or processing artifacts. All tumors were primary and untreated tumors. Normal tissue sections were obtained from histological normal areas within these cases. This consortium included 23 cases of invasive ductal carcinoma of the pancreas, 9 cases of NE tumor of the pancreas, 9 cases of gastric adenocarcinoma, 1 case of adenocarcinoma of small intestine, 6 cases of NE tumor of the small intestine, 2 cases of adenocarcinoma of the appendix, 7 cases of NE tumors of the appendix, 8 cases of colonic adenocarcinoma, 6 cases of colonic NE tumors, and 12 cases of well-differentiated NE tumors (not small cell carcinoma) of the lung (Table 1). NE differentiation was confirmed by immunohistochemistry for synaptophysin. The diagnoses were reconfirmed by a pathologist in this study (KMF).

Table 1.

Expression of AKR1C3 in tumors of pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, and lung

|

Antibody and Immunohistochemistry

Monospecific mouse anti-AKR1C3 monoclonal antibody was produced and characterized in our laboratory as described [14]. Paraffin sections were cut at 5 μm thick, deparaffinized and rehydrated. Single immunohistochemistry for AKR1C3 was performed by an automated staining machine (Benchmark, Ventana; Tucson, AZ) with a CC1-medium antigen retrieval protocol described by the manufacturer. Primary antibody was applied at 1:200 dilution and incubated for 90 min. Diaminobenzidine (DAB) and hematoxylin were used as chromogen and counter stain, respectively.

Double immunohistochemistry was performed first by peroxidase-DAB technique for AKR1C3 as mentioned above, followed by manual immunohistochemistry for rabbit anti-synaptophysin monoclonal antibody (clone SP11; Thermo scientific, Rockford, IL) at a dilution of 1:100 using alkaline phosphatase-fast red technique.

Subtraction of synaptophysin staining was performed by first taking an image from the double immunohistochemistry. Fast red was washed out with alcohol; and another image was then taken at the same location.

Immunohistochemical evaluation and scoring

The stained tissue sections were evaluated with a conventional light microscope by two of the authors (TSC and KMF) independently. The percentage of positive cells within each tumor was evaluated and allocated to one of the following categories: completely negative, ≤ 5% positive immunoreactivity, > 5% but ≤ 25% positive immunoreactivity, > 25% but ≤ 75% positive immunoreactivity, > 75% but ≤ 100% positive immunoreactivity, and 100% positive immunoreactivity. The intensity of staining was also scored as weak, moderate, or strong for every case. In cases with more than one level of intensity, the staining intensity with the largest area was considered the final score.

Results

Normal tissue

AKR1C3 was strongly expressed in the pancreatic ductules but not the acini or islets of Langerhans (Figure 1A and 1B). In gastric and duodenal mucosa, AKR1C3 was widely expressed in the superficially located mucosal cells (close to the luminal surface) but weakly expressed or not expressed in the deeply located epithelial cells such as those in the gastric pits (Figure 2) and Brunner’s gland (Figure 1C). In the terminal ileum and colon, the superficially located mucosal cells closer to the lumen were more AKR1C3-positive immunoreactive than the deeper mucosal epithelial cells (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Expression of AKR1C3 in normal pancreas. Immunoreactivity for AKR1C3 in normal pancreas is limited to the ducts (A and B). The acini and islets of Langerhans (between arrows) are negative. C: ARK1C3 is strongly expressed in the duodenal epithelial cells but only weakly in Brunner’s gland (b). D: AKR1C3 is more strongly expressed in the superficially located mucosal epithelial cells in the colon but not expressed by the deeply located epithelial cells. Original magnification for (A) and (D) is 20x, (B) and (C) is 60x respectively.

Figure 2.

Expression of AKR1C3 and NE marker (synaptophysin) in pancreas and gastrointestinal tract. Double immunohistochemistry (AKR1C3- brown, synaptophysin- red) in duodenum demonstrates widespread expression of AKR1C3 in mucosal cells but not in NE cells (A and B). The red staining in (B) is removed by alcohol wash (C) and the underlying NE cells are negative for AKR1C3 (arrows in B and C). In the stomach, only the more superficially located mucosal cells are immunoreactive for AKR1C3. NE cells (arrow in D) are found in the deeper parts of the mucosa where AKR1C3 is not expressed (D and E). In the bronchial respiratory mucosa, the ciliated mucosal cells are strongly positive for AKR1C3 but NE cells are negative. Original magnification for (A) and (D) is 10x, for (B), (C). (E), and (F) is 60x.

Double immunohistochemistry for AKR1C3 (brown) and synaptophysin (red) demonstrated mutually exclusive expression of the two molecules in different cell populations in distal duodenum (Figure 2A, 2B). Subtraction of synaptophysin revealed that normal NE cells did not express AKR1C3 (arrows in Figure 2C). In oxyntic mucosa of stomach, NE cells were identified in deeply located glands that did not express AKR1C3 (Figure 2D, 2E). Expression of AKR1C3 and synaptophysin was also identified in two distinct populations of cells in the bronchial mucosa (Figure 2F). The pulmonary alveoli were negative for both AKR1C3 and synaptophysin.

Pancreatic tumors

Positive, often strong and diffusely distributed, AKR1C3 immunoreactivity was detected in all 23 cases of invasive ductal carcinoma of the pancreas (Table 1) and (Figure 3A-H), whereas all of 9 pancreatic NE tumor cases were negative for AKR1C3 (Table 1, Figure 3I-P). Among these 9 cases, 6 cases were well-differentiated NE tumor (carcinoid), with one moderately differentiated and two poorly differentiated NE tumors.

Figure 3.

Expression of AKR1C3 in pancreatic tumors. (A) to (D), (E) to (G) are two different cases of invasive pancreatic ductal carcinoma of pancreas with hematoxylin-eosin stain and immunohistochemistry for AKR1C3 respectively. Note the wide spread expression of AKR1C3 with occasional negative tumors (arrow). (I) to (L), (M) to (P) are two different cases of pancreatic NE tumors. Note the negative results and entrapped ducts which act as internal positive control in (K). Original magnification for (A), (C), (E), (G), (I), (K), (M), and (O) is 20x, for (B), (D), (F), (H), (J), (L), (N), (P) is 60x.

Gastric adenocarcinomas

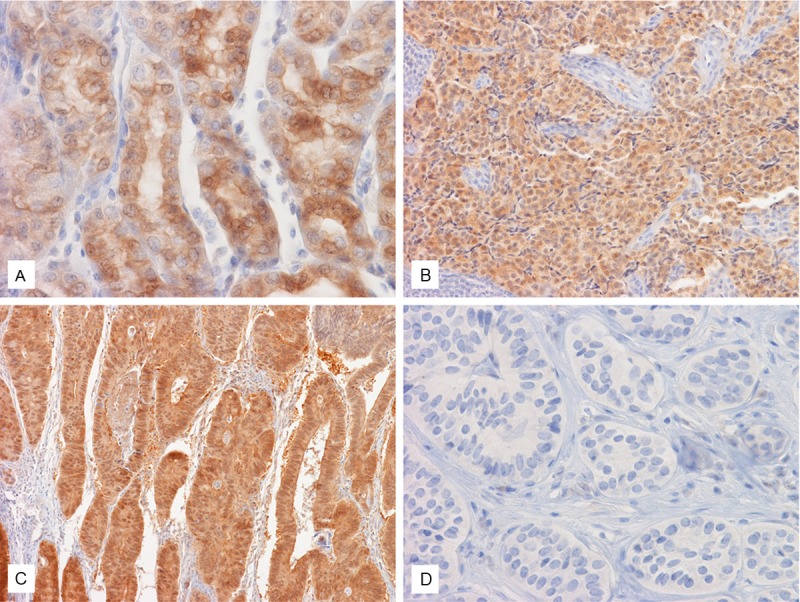

Strong and diffusely distributed AKR1C3-positive immunoreactivities were demonstrated in all 9 cases of gastric adenocarcinomas (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Expression of AKR1C3 in tumors of gastrointestinal tract. Strong expression of AKR1C3 is demonstrated in this case of gastric adenocarcinoma (A), NE tumor of small intestine (B), adenocarcinoma of colon (C) but not NE tumor of colon (D). Original magnification of (A), and (D) is 60x, for (B) and (C) is 20x.

Small intestinal tumors

The only adenocarcinoma of small intestine in this study was negative for AKR1C3. Immuno-reactivity for AKR1C3 was demonstrated in 3 out of 6 cases (50%) of small intestinal well-differentiated NE tumors (Figure 4B).

Appendiceal tumors

No AKR1C3 expression was noted in the two mucinous adenocarcinoma of the appendix (Figure 4C). The 7 well-differentiated NE tumor cases of the appendix were all negative.

Colonic tumors

Positive immunoreactivity for AKR1C3 was demonstrated in 6 out of 8 (75%) cases of colonic adenocarcinoma. One out of the 6 cases (16.7%) of well-differentiated NE tumors was weakly positive for AKR1C3 (Figure 4D).

Pulmonary well-differentiated NE tumor (carcinoid)

Patchy expression of AKR1C3 was demonstrated in 3 out of 12 cases (25%).

Discussion

In this communication, we describe spatial distributions of AKR1C3, a multi-functional enzyme, in normal NE and non-NE epithelial cells as well as neoplastic NE and non-NE malignancies of the pancreas, stomach, small intestine, appendix, colon, and lung. This is the first report describing normal and abnormal expressions of AKR1C3 in these tissues. Our results raise the possibility that AKR1C3 may play a significant role for physiological activity and pathological development of these organs.

We demonstrated a strong expression of AKR1C3 in normal mucosal cells in pancreatic ductules, but not the acini which are anatomically more proximal than the ductal epithelium. Similar observations are demonstrated in the gastric mucosa and duodenum where the surface lining epithelial cells close to the lumen are strongly positive, but epithelial cells deep in the gastric pits and Brunner’s glands in duodenum are either weakly positive or negative. In the appendix and colon, expression of AKR1C3 is stronger in the superficially located epithelial cells close to the lumen as compared to cells in deeper histological locations. These observations corroborate our early finding of strong and widespread expression of AKR1C3 in urothelial epithelium, which line the most distal portion of the urinary system, but only a subset of renal tubules, which is anatomically located proximal to the urothelium [16]. The biological implication of AKR1C3 identified in more superficially and/or distally located epithelial cells observed in the current study is unknown. Physiologically, these distally located epithelial cells protect the interface of the aerodigestive tract from luminal contents, just as the urethelium protects the urinary bladder from urine. In addition to the known diversified biological functions of AKR1C3, we speculate that AKR1C3 may function as part of a chemical barrier in these epithelial cells to defend the body from intrusion of toxic chemicals. The physiological functions of AKR1C3 in superficial mucosal epithelium require further investigation.

In the present study, we also demonstrated that NE cells in the pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, and lung do not express AKR1C3. NE cells have the capability of producing, storing, and secreting peptides and biogenic amines [30]. AKR1C3 is known to regulate the conversion of steroid hormones, PGs, xenobiotics, and chemical carcinogens. The biological significance of the absence of AKR1C3 in NE cells is uncertain. It should be noted that NE cells are found in locations superficial to the lumen of the organ and are surrounded by AKR1C3 expressing non-NE epithelial cells. One speculation is that the diversified function of AKR1C3 breaks down the newly synthesized substances in NE cells and, therefore, AKR1C3 is down-regulated or absent in NE cells.

In one of our previous studies, we demonstrated strong expression of AKR1C3 in squamous cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas of the lung and gastroesophageal junction, but no expression in small cell carcinomas, a highly aggressive NE tumor, of the lung [26]. In the current study, we extend our study and demonstrate expression of AKR1C3 in 88.4% of adenocarcinoma arising from the pancreas and stomach to colon, but only 17.5% of NE tumors arising from the pancreas, small intestine to colon, and lung. Of note, no gastric NE tumors are available in the current study, and the number of cases of adenocarcinoma of the appendix and small intestine is low due to their rarity. In addition, the highest ratio of positive AKR1C3 in NE tumors is found in those arising from the small intestine (50%). All NE tumors of the appendix and pancreas are negative for AKR1C3. AKR1C3 has been demonstrated to be widely expressed in other non-NE carcinomas including those arising from the prostate [16], endometrium [31], urothelium and kidney [27], and breast [19,32]. With the diversified functions of AKR1C3 taken into consideration, AKR1C3 may play an important role in the therapeutic effects of chemotherapy and radiation therapy on these tumors. It may be possible that AKR1C3 can be related to resistance or responsiveness to chemotherapy.

Last but not least, the low expression rate of AKR1C3 in NE tumors and high expression rate in adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, as demonstrated in this investigation and our former studies [16,27,28], may provide an adjunct marker in differential diagnosis between NE and non-NE epithelium-derived tumors.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our most sincere thanks for the technical assistance of Ms. Jeanne Frazer, Danielle Scott, Kelly Smith, Crystal Glass and other staff of the histology laboratory of OU Medical Center. We are also thankful for the technical assistance of Mr. Howard Doughty of the Department of Pathology, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. This project is supported in part by an internal grant awarded to KMF and TSC and a scholarship awarded to LSB. We thank the Peggy and Charles Stephenson Cancer Center at the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, OK and an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P20 GM103639 for the use of Histology and Immunohistochemistry Core, which provides immunohistochemistry service.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Jez JM, Flynn TG, Penning TM. A new nomenclature for the aldo-keto reductase superfamily. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;54:639–647. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)84253-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jez JM, Bennett MJ, Schlegel BP, Lewis M, Penning TM. Comparative anatomy of the aldo-keto reductase superfamily. Biochem J. 1997;326:625–636. doi: 10.1042/bj3260625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hyndman D, Bauman DR, Heredia VV, Penning TM. The aldo-keto reductase superfamily homepage. Chem Biol Interact. 2003;143-144:621–631. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(02)00193-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hara A, Matsuura K, Tamada Y, Sato K, Miyabe Y, Deyashiki Y, Ishida N. Relationship of human liver dihydrodiol dehydrogenases to hepatic bile-acid-binding protein and an oxidoreductase of human colon cells. Biochem J. 1996;313:373–376. doi: 10.1042/bj3130373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dufort I, Soucy P, Labrie F, Luu-The V. Molecular cloning of human type 3 3a-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase that differs from 20a-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase by seven amino acids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;228:474–479. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deyashiki Y, Ogasawara A, Nakayama T, Nakanishi M, Miyabe Y, Sato K, Hara A. Molecular cloning of two human liver 3a-hydroxysteroid/dihydrodiol dehydrogenase isoenzymes that are identical with chlordecone reductase and bile-acid binder. Biochem J. 1994;299:545–552. doi: 10.1042/bj2990545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khanna M, Qin KN, Wang RW, Cheng KC. Substrate specificity, gene structure, and tissue-specific distribution of multiple human 3a-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20162–20168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.34.20162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin HK, Jez JM, Schlegel BP, Peehl DM, Pachter JA, Penning TM. Expression and characterization of recombinant type 2 3a-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD) from human prostate: demonstration of bifunctional 3a/17b-HSD activity and cellular distribution. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:1971–1984. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.13.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dufort I, Rheault P, Huang XF, Soucy P, Luu-The V. Characteristics of a highly labile human type 5 17á-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Endocrinology. 1999;140:568–574. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.2.6531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steckelbroeck S, Jin Y, Gopishetty S, Oyesanmi B, Penning TM. Human cytosolic 3a-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases of the aldo-keto reductase superfamily display significant 3b-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity: implications for steroid hormone metabolism and action. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10784–10795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313308200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penning TM, Burczynski ME, Jez JM, Hung CF, Lin HK, Ma H, Moore M, Palackal N, Ratnam K. Human 3a-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase isoforms (AKR1C1-AKR1C4) of the aldo-keto reductase superfamily: functional plasticity and tissue distribution reveals roles in the inactivation and formation of male and female sex hormones. Biochem J. 2000;351:67–77. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuura K, Shiraishi H, Hara A, Sato K, Deyashiki Y, Ninomiya M, Sakai S. Identification of a principal mRNA species for human 3a-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase isoform (AKR1C3) that exhibits high prostaglandin D2 11-ketoreductase activity. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1998;124:940–946. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Penning TM, Steckelbroeck S, Bauman DR, Miller MW, Jin Y, Peehl DM, Fung KM, Lin HK. Aldo-keto reductase (AKR) 1C3: Role in prostate disease and the development of specific inhibitors. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;248:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin HK, Steckelbroeck S, Fung KM, Jones AN, Penning TM. Characterization of a monoclonal antibody for human aldo-keto reductase AKR1C3 (type 2 3a-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/type 5 17b-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase); immunohistochemical detection in breast and prostate. Steroids. 2004;69:795–801. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rizner TL, Smuc T, Rupreht R, Sinkovec J, Penning TM. AKR1C1 and AKR1C3 may determine progesterone and estrogen ratios in endometrial cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;248:126–135. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fung KM, Samara ENS, Wong C, Metwalli A, Krlin R, Bane B, Liu CZ, Yang JT, Pitha JT, Culkin DJ, Kropp BP, Penning TM, Lin HK. Increased expression of type 2 3a-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/type 5 17b-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (AKR1C3) and its relationship with androgen receptor in prostate carcinoma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13:169–180. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ashley RA, Yu Z, Fung KM, Frimberger D, Kropp BP, Penning TM, Lin HK. Developmental evaluation of aldo-keto reductase 1C3 expression in the cryptorchid testis. Urology. 2010;76:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azzarello J, Fung KM, Lin HK. Tissue distribution of human AKR1C3 and rat homolog in adult genitourinary system. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56:853–861. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2008.951384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis MJ, Wiebe JP, Heathcote JG. Expression of progesterone metabolizing enzyme genes (AKR1C1, AKR1C2, AKR1C3, SRD5A1, SRD5A2) is altered in human breast carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2004;4:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-4-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito K, Utsunomiya H, Suzuki T, Saitou S, Akahira J, Okamura K, Yaegashi N, Sasano H. 17b-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases in human endometrium and its disorders. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;248:136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamura Y, Suzuki T, Nakabayashi M, Endoh M, Sakamoto K, Mikami Y, Moriya T, Ito A, Takahashi S, Yamada S, Arai Y, Sasano H. In situ androgen producing enzymes in human prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12:101–107. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stanbrough M, Bubley G, Ross K, Golub TR, Rubin MA, Penning TM, Febbo PG, Balk SP. Increased expression of genes converting adrenal androgens to testosterone in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2815–2825. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wako K, Kawasaki T, Yamana K, Suzuki K, Jiang S, Umezu H, Nishiyama T, Takahashi K, Hamakubo T, Kodama T, Naito M. Expression of androgen receptor through androgen-converting enzymes is associated with biological aggressiveness in prostate cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:448–454. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2007.050906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahadevan D, DiMento J, Croce KD, Riley C, George B, Fuchs D, Mathews T, Wilson C, Lobell M. Transcriptosome and serum cytokine profiling of an atypical case of myelodysplastic syndrome with progression to acute myelogenous leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2006;81:779–786. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lan Q, Mumford JL, Shen M, Demarini DM, Bonner MR, He X, Yeager M, Welch R, Chanock S, Tian L, Chapman RS, Zheng T, Keohavong P, Caporaso N, Rothman N. Oxidative damage-related genes AKR1C3 and OGG1 modulate risks for lung cancer due to exposure to PAH-rich coal combustion emissions. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:2177–2181. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller VL, Lin HK, Murugan P, Fan M, Penning TM, Brame LS, Yang Q, Fung KM. Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C3 (AKR1C3) is expressed in adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma but not small cell carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5:278–289. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Azzarello JT, Lin HK, Gherezghiher A, Zakharov V, Yu Z, Kropp BP, Culkin DJ, Penning TM, Fung KM. Expression of AKR1C3 in renal cell carcinoma, papillary urothelial carcinoma, and Wilms’ tumor. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2009;3:147–155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park AL, Lin HK, Yang Q, Sing CW, Fan M, Mapstone TB, Gross NL, Gumerlock MK, Martin MD, Rabb CH, Fung KM. Differential expression of type 2 3a/type 5 17b-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (AKR1C3) in tumors of the central nervous system. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2010;3:743–754. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon: IARC Press; 2000. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaltsas GA, Besser GM, Grossman AB. The diagnosis and medical management of advanced neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:458–511. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zakharov V, Lin HK, Azzarello J, McMeekin S, Moore KN, Penning TM, Fung KM. Suppressed expression of type 2 3a/type 5 17b-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (AKR1C3) in endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2010;3:608–617. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han B, Li S, Song D, Poisson-Pare D, Liu G, Luu-The V, Ouellet J, Labrie F, Pelletier G. Expression of 17b-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 and type 5 in breast cancer and adjacent non-malignant tissue: a correlation to clinicopathological parameters. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;112:194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]