Abstract

Background

Exposure of the plasma protein factor XII to an anionic surface generates activated factor XII that not only triggers the intrinsic pathway of blood coagulation through the activatio of factor XI, but also mediates various vascular responses through activation of the plasma contact system. While deficiencies of factor XII are not associated with excessive bleeding, thrombosis models in factor deficient animals have suggested that this protein contributes to stable thrombus formation. Therefore, factor XII has emerged as an attractive therapeutic target to treat or prevent pathological thrombosis formation without increasing the risk for hemorrhage.

Objectives

Utilizing an in vitro directed evolution and chemical biology approach, we sought to isolate a nuclease resistant RNA aptamer that binds specifically to factor XII and directly inhibits factor XII coagulant function.

Methods and Results

Herein, we describe the isolation and characterization of a high affinity RNA aptamer targeting factor XII/XIIa that dose dependently prolongs fibrin clot formation and thrombin generation in clinical coagulation assays. This aptamer functions as a potent anticoagulant by inhibiting the autoactivation of factor XII, as well as inhibiting intrinsic pathway activation (factor XI activation). However, the aptamer does not affect the factor XIIa-mediated activation of the proinflammatory kallikrein-kinin system (plasma kallikrein activation).

Conclusions

We have generated a specific and potent factor XII/XIIa aptamer anticoagulant that offers targeted inhibition of discrete macromolecular interactions involved in the activation of the intrinsic pathway of blood coagulation.

Keywords: RNA Aptamers, Factor XII, Factor XIIa, Anticoagulant Agents, Blood Coagulation

Introduction

The hemostatic system maintains the integrity of the vasculature by sequentially activating a series of proteases, culminating in thrombin production and fibrin clot formation. Activation of coagulation can occur by either exposure of tissue factor (TF) on the vessel wall at the site of injury (extrinsic pathway) or by activation of blood-borne components (factor XII) in the vasculature (intrinsic, or contact activation, pathway) [1]. While the extrinsic pathway is thought to initiate thrombin formation at the site of injury, the intrinsic pathway is thought to mediate continued thrombin generation to stabilize a thrombus [2]. Deficiency of factor XII (FXII) in animals is associated with protection from occlusive thrombus formation after arterial injury and stroke models without interrupting normal hemostatic events [2-4]. While thrombi can still form in these models, they are unstable and fail to occlude the vessel. Thus, pharmacologic inhibition of FXII is an attractive alternative in providing protection from pathologic thrombus formation while minimizing hemorrhagic risk.

Human FXII is an 80kDa glycoprotein consisting of an enzymatic light chain and a heavy chain comprised of several conserved domains that mediate binding to anionic surfaces and other proteins [5]. Binding of the FXII heavy chain to an anionic surface induces a conformational change and results in a small amount of activated FXII (FXIIa) formed [6]. While a number of negatively charged substances have been shown to autoactivate FXII, several compounds thought to be involved in or associated with thrombosis or inflammation, such as polyphosphates [7], nucleic acids [8], protein aggregates [9], and collagen [10] have been identified as potential autoactivators of FXII in vivo. Once activated, FXIIa can then activate FXI and the intrinsic pathway of coagulation to generate thrombin, leading to fibrin clot formation. Additionally, FXIIa can activate plasma kallikrein (PK) to cleave the inflammatory mediator bradykinin (BK) from high-molecular weight kininogen (HK) to facilitate inflammatory responses [11].

Aptamers are single stranded, highly structured oligonucleotides that act as protein antagonists by binding to large surface areas on their target protein. A number of aptamers have been developed as specific and high affinity inhibitors of coagulation proteins that function as potent anticoagulants by interrupting specific complex macromolecular interactions on their target protease [12-15]. The aptamer platform offers a level of control, as each aptamer can be specifically and effectively reversed by either a sequence specific antidote that recognizes and binds to the primary sequence of the aptamer to disrupt aptamer-protein binding [16] or a universal antidote that can reverse the action of any aptamer independent of its sequence [17]. While aptamer technology has been successfully applied to downstream coagulation factors, an aptamer inhibitor of the contact pathway has not yet been reported. Herein, we describe the isolation and characterization of a modified RNA aptamer targeting FXII/FXIIa. This aptamer functions as a potent anticoagulant in a number of clinical coagulation assays, and mediates its anticoagulant effects by inhibiting not only the autoactivation of FXII, but also FXI-mediated intrinsic pathway activation. However, this aptamer does not affect FXIIa-mediated PK activation, demonstrating that aptamers can selectively interfere with specific protein-protein interactions without inhibiting the active site of enzymes.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

Kallikrein, prekallikrein, α-FXIIa, and β-fXIIa, were purchased from Enzyme Research Laboratories (South Bend, IN). FXII, corn trypsin inhibitor (CTI), and all other coagulation proteins were purchased from Haematologic Technologies (Essex Junction, VT). Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was purchased from EMD Chemicals (Gibbstown, NJ), PEG-8000 from Fluka Biochemika (Buchs, Switzerland), dextran sulfate from Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, NJ), and kaolin from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Pacific Hemostasis APTT-XL Reagent was purchased from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA), and TriniCLOT aPTT S and PT Excel from Trinity BioTech (Bray, Co Wicklow, Ireland).

Convergent SELEX

Convergent aptamer selection was performed as described previously [18]. After five rounds of selection against unfractionated normal human pooled plasma (George King Biomedical, Inc., Overland Park, KA), four rounds of selection were performed against purified FXII in Hepes-based buffer (20mM Hepes, 150mM NaCl, 2mM CaCl2, and .01%BSA). The final round was cloned and sequenced as previously described to distinguish individual aptamer sequences [19].

RNA Aptamers

For all aptamer sequences, “C” and “U” represent 2′fluorocytosine and 2′fluorouracil. The full length R4cXII-1 sequence is 5′ - GGGAGGACGAUGCGGCCAAAUCUCGGCUGCCAGCAGGUCACGAGUCGCAAGAUAA CAGACGACUCGCUGAGGAUCCGAGA-3′. The truncated R4cXII-1t sequence is 5′-GGCUCGGCUGCCAGCAGGUCACGAGUCGCAGCGACUCGCUGAGGAUCCGAG-3′. The scrambled control RNA sequence is 5′-GGGGCAGCCGUGGACCGACUGCCGCAUGCCAUUGACAGUCCGAUGCCAGGC-3′. All aptamers were transcribed in vitro as previously described using a modified polymerase [19]. Before use, all aptamer preparations were diluted into a Hepes-based buffer with or without BSA (20mM Hepes, 150mM NaCl, 2mM CaCl2, and with or without 0.01%BSA) as indicated. Diluted aptamers were refolded by heating to 65°C for 5 minutes, and then cooled for 3 minutes at ambient room temperature.

Nitrocellulose filter binding assay

A double-filter nitrocellulose binding assay was employed to determine the apparent binding affinity constants (Kd values) of [y32P] –labeled aptamer to protein as previously described [14, 19].

Clotting Assays

Activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and prothrombin time (PT) assays were performed on a ST4 coagulometer (Diagnostica Stago, Parsippany, NJ). For the aPTT, aptamer (5μL) was added to 50μL normal human pooled plasma (George King Biomedical, Inc., Overland Park, KA) and incubated for 5 minutes at 37°C. APTT-XL (50μL) reagent was added and, after 5 minutes, clotting was initiated with 50μL of 25mM CaCl2. For the PT, refolded aptamer (5μL) was added to 50μL plasma and incubated for 5 minutes at 37°C. TriniClot PT Excel was added to initiate clotting. Aptamer concentrations represent the final concentration in the entire reaction.

FXIIa and FXIa clotting times were run as above, except aptamer (5μL) was incubated with 45μL of either 40nM FXIa or 250nM FXIIa before addition to either FXII or FXI-deficient human plasma (Haematologic Technologies, Essex Junction, VT) supplemented with 3μM phospholipid (15% phosphatidylserine, 41% phosphatidylcholine, 44% phosphatidylethanolamine (Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL)). After 30 seconds at 37°C, clotting was initiated by adding 50μL of 25mM CaCl2.

Thrombin Generation Assay

In an Immulon 2HB clear U-bottom 96 well plate (Thermo Labsystems, Franklin, MA), CTI-treated (50μg/mL), pooled normal human platelet poor plasma from healthy, consented volunteers (60μL) was mixed with aptamer (3μL) and incubated for 5 min at 37°C. Ellagic acid reagent (final concentration 0.1μM, diluted 1:200 with 4μM phospholipid vesicles (20% phosphatidylserine, 60% phosphatidylcholine, 20% phosphatidylethanolamine))(15μL) was added to the plasma-aptamer mixture and incubated for 5 minutes at 37°C. Flu-Ca (Diagnostica Stago)(15μL) was added and thrombin generation was measured using a Fluroskan Ascent Reader (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). A thrombin calibrator reagent (Diagnostica Stago, Parsippany, NJ) was used to quantify the amount of thrombin generated in the samples. Data analysis was performed using Thrombinoscope software (Thrombinoscope BV, the Netherlands). Aptamer concentrations represent the final concentration in the entire reaction. The amount of ellagic acid was standardized to produce a similar curve to a TF-activated TGA. In addition, the amount of CTI present was standardized to inhibit contact activation of the plasma sample, while still allowing for robust FXII-dependent activation upon administration of ellagic acid.

Chromogenic Assays

The following assays were performed in in 96-well flat bottom microtiter plates (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY) at 37 °C in reaction buffer (20mM Hepes, 150mM NaCl, 2mM CaCl2, 0.01%BSA). All protein concentrations are final, and rate of substrate hydrolysis was recorded at 405nm on a Power Wave XS2 kinetic microplate spectrophotometer (Biotek, Winooski, VT). Data were analyzed using the Graphpad Prism Software using linear regression analysis, unless indicated otherwise (GraphPad Prism, GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

FXIIa small peptide substrate cleavage

FXIIa (10nM) was incubated with varying concentrations of either aptamer or CTI for 10 minutes before adding Spectrozyme FXIIa (0.2μM) (American Diagnostica Inc. – now Sekisui Diagnostics, Stamford, CT).

FXII autoactivation assays

FXII (0.2μM) was incubated with varying concentrations of aptamer, dextran sulfate, or buffer for 1 hour before adding Spectrozyme FXIIa. To determine if the aptamer could block autoactivation of FXII, 1μM aptamer or buffer was pre-incubated with FXII for 5 minutes prior to the addition of either dextran sulfate (1μg/mL), kaolin (100μg/mL), micronized silica (30x-diluted), or ellagic acid (30x-diluted). The mixture was incubated for 1 hour before adding Spectrozyme FXIIa (0.2mM).

FXIIa-mediated FXI activation

Aptamer (1μM) or buffer was incubated with FXIIa (5nM) for 5 minutes before adding FXI (25nM). At timed intervals, samples of the reaction were removed, FXIIa activity was quenched by addition of 1μM CTI, and FXIa activity was assayed by the addition of 1mM Pefachrome FXIa (Centerchem, Inc., Norwalk, CT). The amount of FXIa formed was determined by extrapolating from a standard curve using purified FXIa. To determine the inhibition constant (Ki), FXI activation reactions were performed in the presence of varying concentrations of aptamer. The initial rate of FXI activation by FXIIa was determined by linear regression of the amount of FXIa formed versus time for the first 10 minutes of the reaction. Fractional activity (V1/V) was calculated by dividing the initial rate of FXI activation in the presence of aptamer by the initial rate of FXI activation in the absence of aptamer. The Ki was determined using nonlinear regression analysis.

FXIIa-mediated Prekallikrein activation

Aptamer (1μM) or buffer was incubated with FXIIa (4nM) for 5 minutes before adding prekallikrein (20nM). At timed intervals, samples of the reaction were removed and FXIIa activity was quenched by addition of 1μM CTI. Kallikrein activity was assayed by the addition of 0.25mM Pefachrome PK (Centerchem, Inc., Norwalk, CT), The amount of kallikrein formed was determined by extrapolating from a standard curve prepared using purified kallikrein.

Results

Selection of a high affinity FXII-binding aptamer

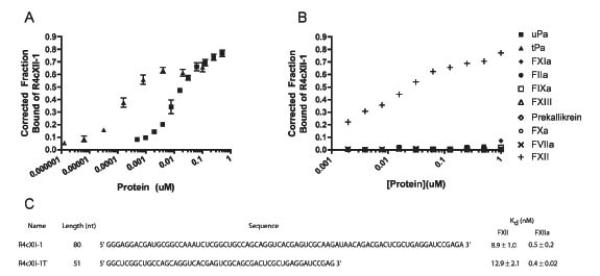

A high affinity aptamer targeting human FXII was isolated from a convergent selection approach, whereby a nucleic-acid-based combinatorial library containing approximately 1014 RNA species was first enriched for binding against the entire human plasma proteome, and then further enriched against purified FXII. To confer greater stability in human plasma, the library contained 2′-fluoropyrimidines [20]. Several RNA species were isolated that bound to both FXII and FXIIa, and of these, one aptamer, R4cXII-1, bound with the highest affinity (dissociation constant Kd of 8.9 ± 1.0nM and a Bmax of 74.8 ± 4.7% to FXII and a Kd of 0.5 ± 0.2nM and a Bmax of 58 ± 3.2% to FXIIa) (Figure 1A, 1C). This binding was also found to be specific, as R4cXII-1 binding to a number of other structurally and functionally related coagulation factors, including thrombin, FXIa, FIXa, FXa, FVIIa, urokinase plasminogen activator, and tissue plasminogen activator, was shown to be non-existent or very weak, with dissociation constants greater than 1000nM and no different from a RNA control (Figure 1B). In addition, R4cXII-1 exhibited greatly reduced binding to β-fXIIa, a cleaved form of FXIIa which is missing part of the heavy chain (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 1. Aptamer R4cXII-1 binds with high affinity to FXII and FXIIa.

Nitrocellulose filter binding assays of aptamer to A) FXII (■) and FXIIa (▲) and B) indicated proteins. C) Linear sequence and dissociation constants of full length R4cXII-1 and truncated R4cXII-1t. In A, the data represent the mean ± SEM of triplicate measures and in B, the data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

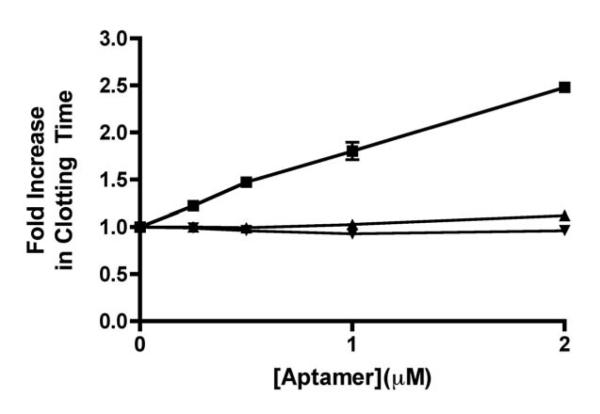

Assessment of aptamer activity in clinical coagulation assays

We next tested aptamer R4cXII-1 for anticoagulant activity in two common coagulation tests, the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and the thrombin generation assay (TGA). The aPTT assay uses a negatively charged substance to strongly activate FXII and thus initiate clotting through the intrinsic pathway. A truncated version of R4cXII-1 (R4cXII-1t) that retained binding affinity to both FXII (apparent Kd of 12.9 ± 2.06nM) and FXIIa (apparent Kd of 0.4 ± 0.02 nM)(Figure 1C) dose dependently anticoagulated human plasma in an aPTT activated with ellagic acid. This inhibition was specific to the intrinsic pathway, as the aptamer had no effect in a PT, which measures the function of the extrinsic pathway of coagulation (Figure 2). In addition, this prolongation was specific to FXII/FXIIa inhibition, as the aptamer dose-dependently prolonged FXIIa clotting times, with no effect on the FXIa clotting time (Supplemental Figure 2). A scrambled control RNA that does not retain binding to FXII/FXIIa had minimal impact on aPTT clotting time (Figure 2). R4cXII-1t also dose-dependently increased clotting time when a micronized silica based reagent was utilized, indicating that inhibition of the intrinsic pathway of coagulation occurs regardless of the FXII activator (data not shown).

Figure 2. Aptamer R4cXII-1t dose dependently anticoagulates human plasma in an aPTT, but not a PT clotting assay.

Effect of R4cXII-1t (■) and scrambled control RNA (▲) in an aPTT and R4cXII-1t (▼) in a PT. The data were normalized to the baseline clot time without aptamer present and represent the mean ± SEM of duplicate measures.

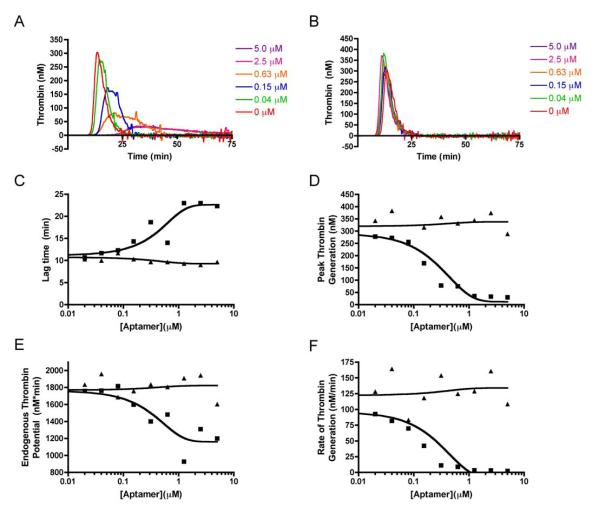

The TGA is a coagulation assay that measures the amount of thrombin generated in human plasma in real-time by monitoring cleavage of a thrombin-specific fluorogenic substrate [21]. Using a TGA allows for several more parameters to be analyzed in addition to the lag time (the time when thrombin begins to appear), including the peak (maximal amount of thrombin formed), the endogenous thrombin potential (ETP, the total amount of thrombin formed), and the rate of thrombin generation (the slope of the line from the lagtime to peak thrombin generation). While a standard TGA is initiated using various concentrations of TF to activate the extrinsic pathway, an assay using diluted ellagic acid as an activator was developed to study effects on thrombin generation during inhibition of FXII. Similar to its activity in an aPTT, R4cXII-1t dose-dependently increased the lag time, as well as decreased peak thrombin generation, ETP, and the rate of thrombin generation in a TGA initiated with ellagic acid (Figure 3). Overall thrombin generation was decreased to background levels, with a clear saturation point of aptamer inhibition (3.75 μM), while the peak amount of thrombin generated and the rate of thrombin generation were robustly inhibited. In contrast, a scrambled control RNA did not inhibit thrombin generation (Figure 3). These data suggest that R4cXII-1 acts as an anticoagulant by specifically inhibiting FXII function to effectively shut down intrinsic pathway activation and thus impair thrombin generation triggered by ellagic acid.

Figure 3. Aptamer R4cXII-1t dose dependently impairs thrombin generation in a TGA assay initiated with ellagic acid.

Thrombograms of normal pooled plasma activated with ellagic acid with various concentrations of A) R4cXII-1t and B) scrambled control RNA. C) Lag time, D) Peak thrombin generation, E) Endogenous thrombin potential, and F) Rate of thrombin generation of R4cXII-1t (■) and scrambled control RNA (▲). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

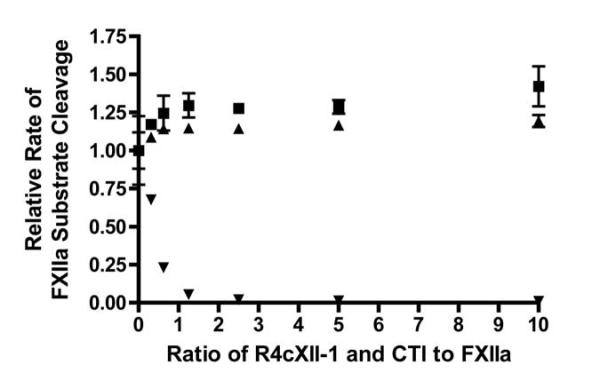

Assessment of aptamer activity on FXII active site function

To elucidate the mechanism of intrinsic pathway inhibition, a series of purified protein assays were performed. First, the impact of aptamer binding on active site function of FXIIa was determined by monitoring the cleavage of a small peptide chromogenic substrate in the presence of a range of aptamer concentrations, scrambled control RNA, and a known FXIIa active site inhibitor, CTI. While CTI potently and dose dependently inhibited the ability of FXIIa to cleave the small peptide chromogenic substrate, both the control RNA and R4cXII-1 did not affect small-substrate cleavage (Figure 4). These data indicate that the anticoagulant effect of the aptamer is not due to the inhibition of the active site on FXIIa. Because aptamers tend to impede protein-protein interactions without affecting the active site[22], the ability of the aptamer to inhibit FXII/FXIIa-mediated macromolecular interactions was next evaluated.

Figure 4. Aptamer R4cXII-1 does not inhibit FXIIa cleavage of a small peptide substrate.

FXIIa was incubated with varying amounts of R4cXII-1 (■), scrambled control RNA (▲), and CTI (▼), and active site activity was measured with a chromogenic substrate. The data were normalized to the rate in the absence of compound and represent the mean ± SEM of duplicate measures.

Assessment of aptamer activity on FXII autoactivation

Since a range of anionic compounds, including unmodified nucleic acids [8], have been found to autoactivate FXII, aptamer and scrambled control RNA were tested to determine if relatively short 2′fluoropyrimidine modified RNAs could also autoactivate FXII. While dextran sulfate was able to convert FXII to FXIIa with the characteristic bell-shaped concentration curve of a template-related mechanism [23], neither the control RNA nor R4cXII-1 could autoactivate FXII over a wide range of concentrations (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Aptamer R4cXII-1 does not induce autoactivation of FXII but blocks the activities of several autoactivators of FXII.

A) FXII was incubated with varying amounts of dextran sulfate (■), R4cXII-1 (▲), or scrambled control RNA (▼), and assayed for the amount of FXIIa formed. The data represent the mean ± SEM of triplicate measures. B) FXII was pre-incubated with R4cXII-1 (black bars) or scrambled control RNA (grey bars) before addition of the indicated autoactivator, and assayed for the amount of FXIIa formed. The data were normalized to the rate in the absence of aptamer and represent the mean ± SEM of triplicate measures.

Next, the ability of R4cXII-1 to block the autoactivation of FXII by various known activators was tested. Dextran sulfate, as well as purified kaolin, and standardized aPTT reagents including micronized silica (TriniClot S) and ellagic acid (APTT-XL) were all tested and found to activate FXII at widely different rates (data not shown). The final concentration of each activator that yielded an optimal rate of autoactivation of FXII was used for further studies. R4cXII-1 was able to greatly inhibit the ability of dextran sulfate and micronized silica to autoactivate FXII, and partially inhibit the ability of kaolin and ellagic acid to autoactivate FXII (Figure 5B). In contrast, a scrambled control RNA was not able to inhibit autoactivation by any activator. Autoactivation assays conducted with physiologic activators, such as polyphosphates, were hampered by the necessity for the aptamer buffer to contain divalent ions, which assist in proper aptamer folding but inhibit the ability of these physiologic activators to measurably autoactivate FXII (data not shown).

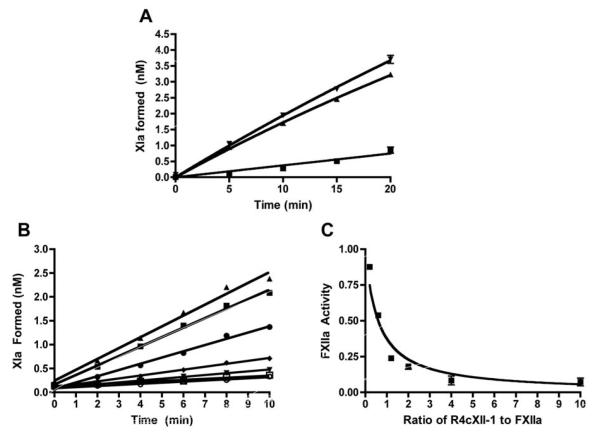

Assessment of aptamer activity on FXIIa-mediated activation of biologic substrates

Once activated, FXIIa can subsequently activate FXI to propagate the intrinsic pathway of coagulation. The ability of R4cXII-1 to inhibit FXIIa-mediated FXI activation was assessed by monitoring the amount of FXIa formed in a purified system containing FXIIa as an activator. The presence of R4cXII-1 reduced the initial rate of FXI activation by greater than ~90%, while the presence of a scrambled control RNA did not (Figure 6A). To determine the potency of inhibition, the initial rate of FXI activation by FXIIa was measured in the presence of varying concentrations of R4cXII-1. As shown in Figure 6B, R4cXII-1 concentration-dependently decreased the amount of FXIa formed, with an apparent equilibrium inhibition constant (Ki) of 3.0nM ± 0.3nM (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. Aptamer R4cXII-1 dose dependently inhibits FXIIa-catalyzed activation of FXI.

A) FXI was activated by FXIIa, the reaction was quenched at various time-points and assayed for the amount of FXIa formed in the presence of R4cXII-1 (■), scrambled control RNA (▼), or buffer (▲). The data represent the mean ± SEM of triplicate measures. B) The amount of FXIa formed was determined in the presence of R4cXII-1 at concentrations of 0nM(▲), 1nM (■), 3nM (•), 6nM (◆), 10nM (▼), 20nM (□), 50nM (○). The data are representative of three independent measures. C) Fractional activity of R4cXII-1 versus the ratio of R4cXII-1 to FXII present in the reaction. The data represent the mean ± SEM of triplicate measures.

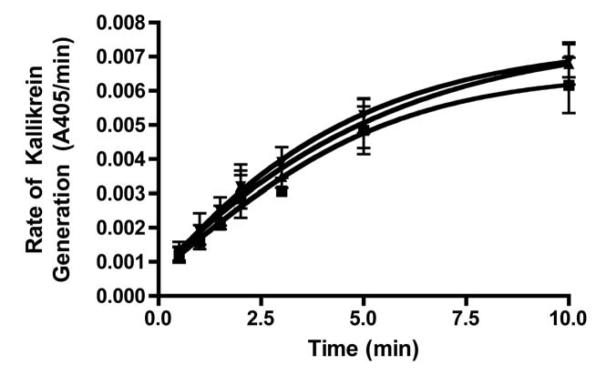

Aside from activating the intrinsic pathway through FXI activation, FXIIa can also activate PK, which in turn reciprocally activates more FXII in a feedback loop that amplifies the activation of the contact pathway, as well as initiates the inflammatory kallikrein-kinin system [11, 24]. The ability of R4cXII-1 to inhibit PK activation by FXIIa was examined by monitoring the amount of kallikrein formed in a purified system using FXIIa as an activator. In contrast to the ability of R4cXII-1 to inhibit the generation of activated FXI (Figure 6A), the aptamer did not affect PK activation by FXIIa compared to buffer or a scrambled control RNA (Figure 7). This indicates that R4cXII-1 does not bind to FXIIa in a manner that inhibits FXIIa-PK interactions, while it does inhibit FXIIa-FXI interactions. Collectively, these data suggest that R4cXII-1 is a potent inhibitor of both the autoactivation of FXII and FXIIa-mediated activation of FXI, while having no effect on PK activation.

Figure 7. Aptamer R4cXII-1 does not inhibit the ability of FXII to activate prekallikrein.

Prekallikrein was activated by FXIIa, the reaction was quenched at various time points and assayed for the amount of kallikrein formed in the presence of R4cXII-1 (▼), scrambled control RNA (▲), or buffer (■).The data represent the mean ± SEM of triplicate measures.

Discussion

Herein, we describe the isolation and characterization of a novel FXII/FXIIa inhibitor (Supplemental Figure 3). A nuclease resistant, 2′ fluoropyrimidine modified RNA aptamer was isolated using in vitro iterative selection methods. Similar to other aptamers targeting coagulation factors, this aptamer binds with high affinity to both FXII and FXIIa and is a potent anticoagulant in common clinical coagulation assays [12-15]. Although the aptamer does not inhibit the active site of FXIIa, it functions as an anticoagulant by both inhibiting the autoactivation of FXII and inhibiting FXIIa-mediated activation of FXI, thus effectively shutting down thrombin generation in a plasma-based setting by blocking dual functions of FXII/FXIIa. Additionally, the aptamer does not impede the ability of FXIIa to activate PK.

Taken together, the data indicate that the aptamer binds to a region on the heavy chain of FXII/FXIIa implicated in anionic and FXI binding, which is spatially separate from where PK binds to FXII. Although a crystal structure of FXII is not available, domain mapping has suggested a closely located binding site for FXI and anionic surfaces in the N-terminus fibronectin type II domain [5]. Studies on thrombin aptamers have determined that an aptamer binds by presenting an extended surface complementary to the protein binding site [22], and subsequently sterically interferes with macromolecular interactions formed between the aptamer binding region and large protein substrates, while allowing other distant exosites and active sites to function [14]. Interestingly, other putative binding sites on FXII for anionic molecules exist in separate domains [25]. As distinct anionic compounds bind discretely to FXII and autoactivate FXII at different rates, this binding to different, and possibly partially overlapping, domains could explain why the aptamer was not able to inhibit the autoactivation of FXII by various autoactivators to the same degree. Continued studies into aptamer binding and function could help to further delineate the regions involved in macromolecular substrate interaction [5], especially the differential binding of anionic molecules to FXII.

The ability to inhibit the intrinsic pathway of coagulation while leaving the kallikrein-kinin system intact will be beneficial in parsing out the importance of FXIIa functions in vivo. While all members of the contact pathway have been implicated in thrombosis through studying various knockdown or knockout animal models, it is not entirely clear which FXIIa-mediated process, inflammation or coagulation, plays the primary part in contributing to thrombosis [2, 3, 26-28]. Targeted inhibition or animal knockout models have suggested that FXIIa-mediated FXI activation is responsible for thrombotic protection in injury models due to similar thrombotic protection profiles of FXI and FXII deficient animals [2, 4, 27, 29]. Utilizing a specific inhibitor of the intrinsic pathway, while leaving the kallikrein-kinin system intact, would be valuable in parsing out the various functions of FXIIa in thrombosis.

The development of a TGA assay triggered by FXII is instrumental for studying the functions of contact pathway in plasma thrombin generation. While the aPTT proceeds through the contact pathway, the TGA is commonly triggered by the extrinsic pathway activator TF, and is thus not sensitive to deficiencies or inhibitors of FXII [30]. Both the aPTT and modified TGA assays, which use the same activator at different strengths, exhibit a dose-dependent increase in the time it takes for thrombin or a clot to form with R4cXII-1 present. However, the TGA also showed the ability of the aptamer to robustly decrease the total amount of thrombin formed, the peak amount of thrombin generation, and the overall rate of thrombin generation. Importantly, the rate of thrombin generation has previously been shown to be a key contributor in influencing clot stability, with a slower rate of thrombin generation associated with less stable clots [31]. The finding that FXII inhibition decidedly decreases the rate of thrombin generation in this assay is consistent with observations that FXII inhibition or deficiency is antithrombotic, potentially due to formation of unstable thrombi that can easily break up in thrombosis models under flow [2, 3].

Through in vitro and animal studies, FXII has been well established as an important mediator of thrombotic effects, while not affecting normal hemostatic function. In thrombosis, it is hypothesized that aggregated proteins, activated platelets, and polyphosphate, among other compounds present at a developing thrombus, can contribute to the continued activation of FXII and the intrinsic pathway, leading to excessive thrombin generation to exacerbate the growth of the thrombus [32]. Inhibition of the autoactivation of FXII, as well as a significant decrease in the rate of thrombin generated at the site of a growing thrombus through targeted inhibition of the intrinsic pathway of coagulation, could be a viable antithrombotic strategy in a number of clinical settings. While clinical studies have not always mirrored the results seen in FXII deficient animal models, further analysis into the utility of targeted inhibition of the intrinsic pathway of coagulation is warranted. Currently, an aptamer generated against Factor IXa and its matched oligonucleotide antidote are making their way through clinical development [12, 33]. We anxiously await the clinical evaluation of other aptamers targeting upstream coagulation factors, such as FXII, that may not require antidotes to be safe and effective antithrombotic agents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Kunal Desai and Lyndon Mitnaul to the design and conduct of these studies. We are grateful to Richard Becker for critical review of the manuscript. This work was supported by an NIH grant to BAS (RO1HL65222) and Merck.

Footnotes

Addendum R.S.W. designed and performed research, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. J.L. and W.W. performed research, Y.X. designed and performed research and analyzed data, M.L.O. coordinated research and analyzed data, and B.A.S. designed and coordinated research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest: B.A.S. is a scientific founder of Regado Biosciences, Inc. J.L. is a current employee of Regado Biosciences, Inc. M.L.O, W.W, and Y.X. are employees of Merck & Co., Inc.

Supporting Information Figure S1. Aptamer R4cXII-1 binds with reduced affinity to β-fXIIa.

Figure S2. Aptamer R4cXII-1t dose dependently inhibits FXIIa-clotting times, but not FXIa-clotting times.

Figure S3. A schematic depicting the role of the FXII aptamer, R4cXII-1, in inhibiting FXII/FXIIa function.

References

- 1.Hoffman M. A cell-based model of coagulation and the role of factor VIIa. Blood Rev. 2003;17(Suppl 1):S1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0268-960x(03)90000-2. S0268960X03900002 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Renne T, Pozgajova M, Gruner S, Schuh K, Pauer HU, Burfeind P, Gailani D, Nieswandt B. Defective thrombus formation in mice lacking coagulation factor XII. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;202:271–81. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050664. jem.20050664 [pii] 10.1084/jem.20050664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleinschnitz C, Stoll G, Bendszus M, Schuh K, Pauer HU, Burfeind P, Renne C, Gailani D, Nieswandt B, Renne T. Targeting coagulation factor XII provides protection from pathological thrombosis in cerebral ischemia without interfering with hemostasis. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2006;203:513–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052458. jem.20052458 [pii] 10.1084/jem.20052458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng Q, Tucker EI, Pine MS, Sisler I, Matafonov A, Sun MF, White-Adams TC, Smith SA, Hanson SR, McCarty OJ, Renne T, Gruber A, Gailani D. A role for factor XIIa-mediated factor XI activation in thrombus formation in vivo. Blood. 2010;116:3981–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270918. 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stavrou E, Schmaier AH. Factor XII: what does it contribute to our understanding of the physiology and pathophysiology of hemostasis & thrombosis. Thrombosis research. 2010;125:210–5. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2009.11.028. 10.1016/j.thromres.2009.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samuel M, Pixley RA, Villanueva MA, Colman RW, Villanueva GB. Human factor XII (Hageman factor) autoactivation by dextran sulfate. Circular dichroism, fluorescence, and ultraviolet difference spectroscopic studies. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1992;267:19691–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muller F, Mutch NJ, Schenk WA, Smith SA, Esterl L, Spronk HM, Schmidbauer S, Gahl WA, Morrissey JH, Renne T. Platelet polyphosphates are proinflammatory and procoagulant mediators in vivo. Cell. 2009;139:1143–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.001. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kannemeier C, Shibamiya A, Nakazawa F, Trusheim H, Ruppert C, Markart P, Song Y, Tzima E, Kennerknecht E, Niepmann M, von Bruehl ML, Sedding D, Massberg S, Gunther A, Engelmann B, Preissner KT. Extracellular RNA constitutes a natural procoagulant cofactor in blood coagulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:6388–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608647104. 0608647104 [pii] 10.1073/pnas.0608647104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maas C, Govers-Riemslag JW, Bouma B, Schiks B, Hazenberg BP, Lokhorst HM, Hammarstrom P, ten Cate H, de Groot PG, Bouma BN, Gebbink MF. Misfolded proteins activate factor XII in humans, leading to kallikrein formation without initiating coagulation. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3208–18. doi: 10.1172/JCI35424. 10.1172/JCI35424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Meijden PE, Munnix IC, Auger JM, Govers-Riemslag JW, Cosemans JM, Kuijpers MJ, Spronk HM, Watson SP, Renne T, Heemskerk JW. Dual role of collagen in factor XII-dependent thrombus formation. Blood. 2009;114:881–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-171066. 10.1182/blood-2008-07-171066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sainz IM, Pixley RA, Colman RW. Fifty years of research on the plasma kallikrein-kinin system: from protein structure and function to cell biology and in-vivo pathophysiology. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2007;98:77–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rusconi CP, Scardino E, Layzer J, Pitoc GA, Ortel TL, Monroe D, Sullenger BA. RNA aptamers as reversible antagonists of coagulation factor IXa. Nature. 2002;419:90–4. doi: 10.1038/nature00963. 10.1038/nature00963 nature00963 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rusconi CP, Yeh A, Lyerly HK, Lawson JH, Sullenger BA. Blocking the initiation of coagulation by RNA aptamers to factor VIIa. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2000;84:841–8. 00110841 [pii] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bompiani KM, Monroe DM, Church FC, Sullenger BA. A high affinity, antidote-controllable prothrombin and thrombin-binding RNA aptamer inhibits thrombin generation and thrombin activity. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2012;10:870–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04679.x. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04679.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buddai SK, Layzer JM, Lu G, Rusconi CP, Sullenger BA, Monroe DM, Krishnaswamy S. An anticoagulant RNA aptamer that inhibits proteinase-cofactor interactions within prothrombinase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:5212–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.049833. 10.1074/jbc.M109.049833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rusconi CP, Roberts JD, Pitoc GA, Nimjee SM, White RR, Quick G, Jr., Scardino E, Fay WP, Sullenger BA. Antidote-mediated control of an anticoagulant aptamer in vivo. Nature biotechnology. 2004;22:1423–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt1023. nbt1023 [pii] 10.1038/nbt1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oney S, Lam RT, Bompiani KM, Blake CM, Quick G, Heidel JD, Liu JY, Mack BC, Davis ME, Leong KW, Sullenger BA. Development of universal antidotes to control aptamer activity. Nat Med. 2009;15:1224–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.1990. nm.1990 [pii] 10.1038/nm.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oney S, Nimjee SM, Layzer J, Que-Gewirth N, Ginsburg D, Becker RC, Arepally G, Sullenger BA. Antidote-controlled platelet inhibition targeting von Willebrand factor with aptamers. Oligonucleotides. 2007;17:265–74. doi: 10.1089/oli.2007.0089. 10.1089/oli.2007.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Layzer JM, Sullenger BA. Simultaneous generation of aptamers to multiple gamma-carboxyglutamic acid proteins from a focused aptamer library using DeSELEX and convergent selection. Oligonucleotides. 2007;17:1–11. doi: 10.1089/oli.2006.0059. 10.1089/oli.2006.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keefe AD, Cload ST. SELEX with modified nucleotides. Current opinion in chemical biology. 2008;12:448–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.06.028. S1367-5931(08)00109-9 [pii] 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hemker HC, Giesen P, Al Dieri R, Regnault V, de Smedt E, Wagenvoord R, Lecompte T, Beguin S. Calibrated automated thrombin generation measurement in clotting plasma. Pathophysiology of haemostasis and thrombosis. 2003;33:4–15. doi: 10.1159/000071636. 71636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Long SB, Long MB, White RR, Sullenger BA. Crystal structure of an RNA aptamer bound to thrombin. RNA. 2008;14:2504–12. doi: 10.1261/rna.1239308. rna.1239308 [pii] 10.1261/rna.1239308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Citarella F, Wuillemin WA, Lubbers YT, Hack CE. Initiation of contact system activation in plasma is dependent on factor XII autoactivation and not on enhanced susceptibility of factor XII for kallikrein cleavage. British journal of haematology. 1997;99:197–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.3513165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cochrane CG, Revak SD, Wuepper KD. Activation of Hageman factor in solid and fluid phases. A critical role of kallikrein. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1973;138:1564–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.138.6.1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Citarella F, Ravon DM, Pascucci B, Felici A, Fantoni A, Hack CE. Structure/function analysis of human factor XII using recombinant deletion mutants. Evidence for an additional region involved in the binding to negatively charged surfaces. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS. 1996;238:240–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0240q.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shariat-Madar Z, Mahdi F, Warnock M, Homeister JW, Srikanth S, Krijanovski Y, Murphey LJ, Jaffa AA, Schmaier AH. Bradykinin B2 receptor knockout mice are protected from thrombosis by increased nitric oxide and prostacyclin. Blood. 2006;108:192–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-0094. 10.1182/blood-2006-01-0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Revenko AS, Gao D, Crosby JR, Bhattacharjee G, Zhao C, May C, Gailani D, Monia BP, MacLeod AR. Selective depletion of plasma prekallikrein or coagulation factor XII inhibits thrombosis in mice without increased risk of bleeding. Blood. 2011;118:5302–11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-355248. 10.1182/blood-2011-05-355248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosen ED, Gailani D, Castellino FJ. FXI is essential for thrombus formation following FeCl3-induced injury of the carotid artery in the mouse. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2002;87:774–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H, Lowenberg EC, Crosby JR, MacLeod AR, Zhao C, Gao D, Black C, Revenko AS, Meijers JC, Stroes ES, Levi M, Monia BP. Inhibition of the intrinsic coagulation pathway factor XI by antisense oligonucleotides: a novel antithrombotic strategy with lowered bleeding risk. Blood. 2010;116:4684–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-277798. 10.1182/blood-2010-04-277798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keularts IM, Zivelin A, Seligsohn U, Hemker HC, Beguin S. The role of factor XI in thrombin generation induced by low concentrations of tissue factor. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2001;85:1060–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allen GA, Wolberg AS, Oliver JA, Hoffman M, Roberts HR, Monroe DM. Impact of procoagulant concentration on rate, peak and total thrombin generation in a model system. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2004;2:402–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7933.2003.00617.x. 617 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Renne T, Schmaier AH, Nickel KF, Blomback M, Maas C. In vivo roles of factor XII. Blood. 2012;120:4296–303. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-292094. 10.1182/blood-2012-07-292094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Povsic TJ, Wargin WA, Alexander JH, Krasnow J, Krolick M, Cohen MG, Mehran R, Buller CE, Bode C, Zelenkofske SL, Rusconi CP, Becker RC. Pegnivacogin results in near complete FIX inhibition in acute coronary syndrome patients: RADAR pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic substudy. European heart journal. 2011;32:2412–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr179. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.