Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Little is known about the prognostic impact of hypoglycemia associated with hospitalization. We hypothesized that hospitalized hypoglycemia would be associated with increased long-term morbidity and mortality, irrespective of diabetes status.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

We undertook a cohort study using linked administrative health care and laboratory databases in Alberta, Canada. From 1 January 2004 to 31 March 2009, we included all outpatients 66 years of age and older who had at least one serum creatinine and one A1C measured. To examine the independent association between hospitalized hypoglycemia and all-cause mortality, we used time-varying Cox proportional hazards (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR]), and for all-cause hospitalizations, we used Poisson regression (adjusted incidence rate ratio [aIRR]).

RESULTS

The cohort included 85,810 patients: mean age 75 years, 51% female, and 50% had diabetes defined by administrative data. Overall, 440 patients (0.5%) had severe hypoglycemia associated with hospitalization and most (93%) had diabetes. During 4 years of follow-up, 16,320 (19%) patients died. Hospitalized hypoglycemia was independently associated with increased mortality (60 vs. 19% mortality for no hypoglycemia; aHR 2.55 [95% CI 2.25–2.88]), and this increased in a dose-dependent manner (aHR no hypoglycemia = 1.0 vs. one episode = 2.49 vs. one or more = 3.78, P trend <0.001). Hospitalized hypoglycemia was also independently associated with subsequent hospitalizations (aIRR no hypoglycemia = 1.0 vs. one episode = 1.90 vs. one or more = 2.61, P trend <0.001) and recurrent hypoglycemia (aHR no hypoglycemia = 1.0 vs. one episode = 2.45 vs. one or more = 9.66, P trend <0.001).

CONCLUSIONS

Older people who have an episode of hospitalized hypoglycemia are easily identified and at substantially increased risk of morbidity and mortality.

Relatively little has been reported regarding severe hypoglycemia, particularly outside the setting of diabetes and its treatments or beyond the context of strict glycemic control in the perioperative or critical care setting (1–5). Among the standard diabetes treatment arms of the ADVANCE (Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron MR Controlled Evaluation) and ACCORD (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes) trials, rates of severe hypoglycemia requiring medical attention ranged between 1.5 and 3.4% over 4–5 years (6,7), and attempts at determining population-based rates of severe nondiabetic hypoglycemia suggest a rate of 50 per 10,000 hospital admissions (5). Whether examined in diabetes-related outpatient cohorts (8–12), in trials of intensive glycemic control (13), or in the setting of acute illness (14–16), severe hypoglycemia is often associated with an increase in all-cause mortality and other major adverse events.

To our knowledge, there are no reports examining the long-term prognostic impact of an episode of severe hypoglycemia associated with hospitalization that occurs in community-dwelling older adults, particularly those without diabetes. Therefore, we undertook a population-based cohort study using linked health care databases to determine the prognostic impact of severe hypoglycemia associated with hospitalization on long-term morbidity and mortality. We hypothesized that an episode of hospitalized hypoglycemia would be independently associated with an increased risk of all-cause hospitalization and all-cause mortality, and we speculated that there would be a dose-response relationship between the number of hypoglycemic episodes and major adverse events.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Setting and subjects

Data from the Alberta Kidney Disease Network and the provincial health ministry (Alberta Health) were used for this study (17). This database includes data from all Alberta residents who had serum creatinine measurements taken as part of clinical care provided in Alberta between 2002 and 2009. Because kidney function and A1C are both plausible confounders of the association between hypoglycemia and mortality, we studied all outpatients 66 years of age and older who had both an outpatient serum creatinine and A1C measured within 6 months of each other in Alberta between 1 January 2004 and 31 March 2009. The “index date” defines the moment of entry into the study cohort proper, and it is the date on which each individual outpatient had both A1C and serum creatinine available. We estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study equation. Because patients with advanced kidney failure (eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 or receiving dialysis before their first [index] creatinine measurement) have differential risks of death and hypoglycemia compared with those without, and they represent a small relatively atypical population, we excluded them from our cohort. Institutional review boards for the University of Alberta and University of Calgary approved the study.

Exposures

The exposure of interest in this study was an episode of severe (acute) hypoglycemia associated with hospitalization occurring at any time during follow-up. For analytic purposes, we considered an episode of hospitalized hypoglycemia to be similar to a drug exposure, and thus considered people exposed or not exposed. The conventional definition of severe hypoglycemia is a low blood glucose measurement associated with symptoms of sufficient severity that third party or medical assistance is required (1,2,6–9). Because we were explicitly interested in the prognosis of severe hypoglycemia associated with hospitalization, we considered primary (most responsible) or secondary or even in-hospital complications discharge diagnoses to represent an “exposure.” Thus, like others (10–12), we defined severe hypoglycemia by the presence of any inpatient discharge diagnosis of hypoglycemia (ICD-10 code E15 or E16). We did not have similarly detailed or validated data regarding outpatient visits (e.g., emergency department visits or unscheduled primary care visits) related to hypoglycemia and acknowledge that this is a limitation of our study. We categorized severe hypoglycemia episodes as none, one, or more than one to explore dose-response relationships.

Outcomes

The primary outcome for this study was all-cause mortality. Secondary end points included all-cause hospitalizations and hypoglycemia-associated hospitalizations; as we considered any hospitalization to be an adverse event, any event that occurred after the next calendar day after discharge was captured and considered an outcome. Mortality and dates of hospitalization were determined by linkage to the databases of the provincial health ministry (17,18).

Other measurements

We identified diabetes using previously validated algorithms (i.e., two physician billing claims in a 2-year period or one hospital discharge ever with a diagnosis of diabetes, excluding gestational diabetes mellitus); in Alberta, this coding algorithm is associated with a sensitivity of 92.3%, specificity of 96.9%, positive predictive value of 77.2%, and negative predictive value of 99.3% (19). Patients were also classified into three mutually exclusive groups based on their first A1C measurement during the study: A1C <6% (<42 mmol/mol) vs. A1C 6–8% (42–64 mmol/mol) vs. A1C >8% (>64 mmol/mol). By study definition, these measures of A1C were taken before the hypoglycemic event and were unrelated to the event. Comorbidities present in the 3 years prior to the index date were assessed using physician claims and hospitalization data together with validated algorithms for the variables listed in Table 1 (17–20). Socioeconomic data included location of residence and median household income based on postal codes. Data were not available on whether participants resided in an institutional setting. In Alberta, drug insurance is provided to all residents >65 years of age, allowing us to capture dispensation data for insulin and oral hypoglycemic agents. Other than insulin, no other injectable hypoglycemic agents were available during the study. Drug exposure was defined as at least one dispensation (3-month supply) in the 1 year prior to index date.

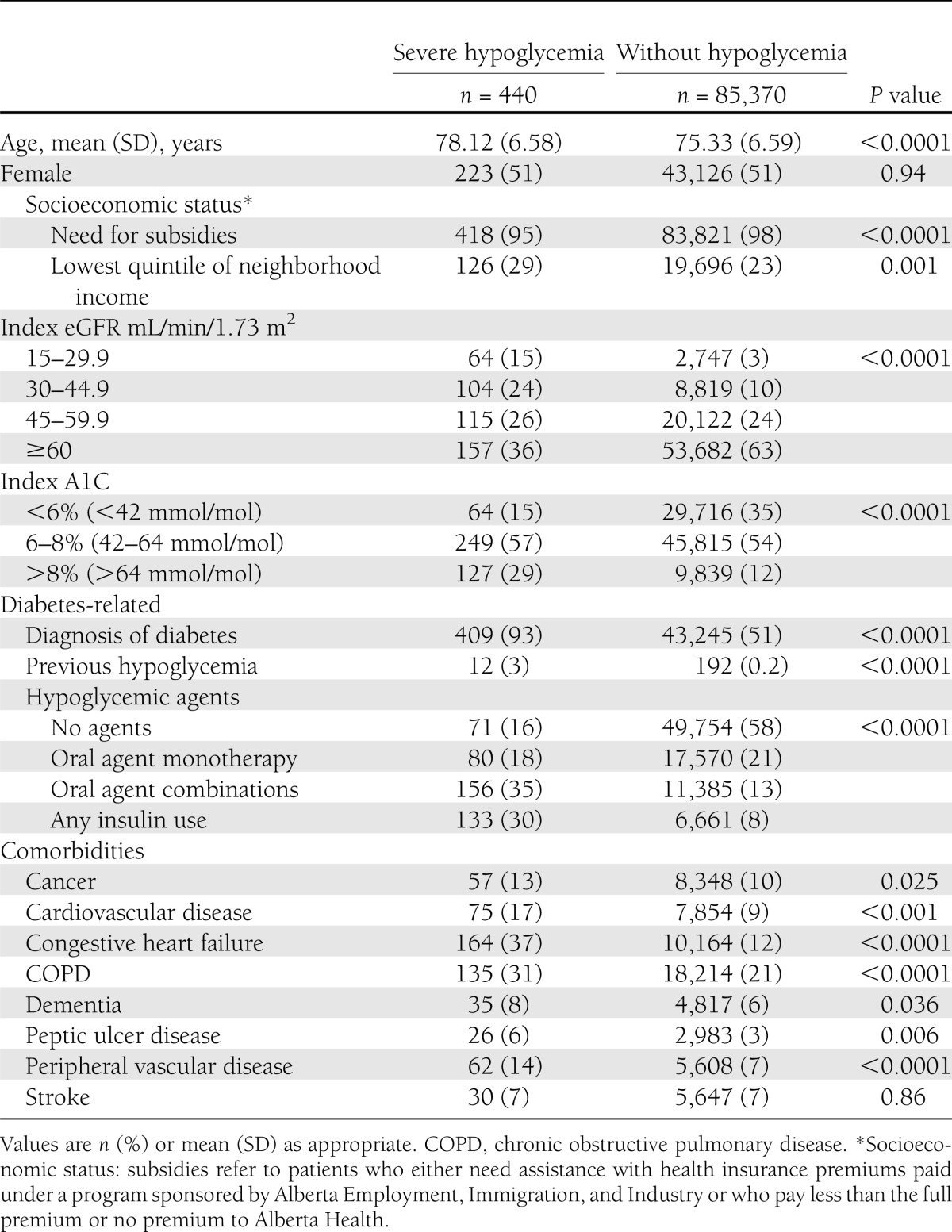

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of 85,810 older patients, according to the presence or absence of severe (hospitalized) hypoglycemia

Statistical analysis

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics stratified by the presence or absence of severe hypoglycemia were given as means or proportions. For analyses related to all-cause mortality and recurrent hypoglycemia, we used multivariable Cox proportional hazards models. Akin to the widely accepted new-user design exploring a new drug exposure (21), we specifically considered incident (postindex date) severe hypoglycemia as our exposure of interest and studied it as a time-varying covariate during the course of follow-up. In this manner, subjects accrued person-time as either exposed or not exposed to hypoglycemia, although any individual subject could contribute person-time as not exposed (before the hypoglycemic episode if there was one) or exposed (after the hypoglycemic episode) (22). The only purposeful departure from the new-user approach we undertook for our primary analysis was including subjects who had had an episode of hospitalized hypoglycemia in the 1 year prior to study entry (i.e., some subjects had a prevalent exposure). We conducted a sensitivity analysis where we excluded these patients to better mimic the new-user approach (see below). Censoring occurred with death, disenrollment from the health plan (i.e., permanent departure from the province), or the end-of-study date on 31 March 2009. The proportional hazards assumptions were tested using visual inspection of the log-negative-log survival plots, and no violations were noted. All models were adjusted for the following potential confounders: age, sex, socioeconomic status (based on individual health insurance premium level and median neighborhood income [18]), index eGFR, prevalent hypoglycemia (i.e., hospitalization with hypoglycemia in the 1 year prior to the index date), comorbidities, diabetes, and use of diabetes medications (i.e., insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents within 6 months before and after the index date). For analyses related to all-cause hospitalization rates, we used multivariable Poisson regression models with the number of days at risk as offset, controlling for the same variables as listed above. To manage overdispersion, we used robust variance estimations for calculating P values and 95% CIs.

We undertook several sensitivity and exploratory analyses with respect to the main outcome of all-cause mortality. Each of the presented analyses was drawn from the parent cohort, and so each analysis is mutually exclusive, and the analyses do not represent serial restrictions. First, we repeated analyses after excluding all patients from the original cohort with a diagnosis of diabetes based on administrative data at the time of study entry. Second, we repeated analyses after excluding from the original cohort all patients who had prevalent hypoglycemia, i.e., any episode of severe hypoglycemia in the 1 year prior to the index date. Third, we repeated analyses in the original cohort after redefining hospitalized hypoglycemia (our main exposure) as only the primary most-responsible diagnosis for admission, i.e., if hypoglycemia was one of the secondary or in-hospital complications diagnoses at discharge, it was no longer counted as an exposure, and those patients were considered not to have had hospitalized hypoglycemia. Fourth, we repeated analyses in the original cohort after again redefining hospitalized hypoglycemia (our main exposure) as primary or secondary diagnosis for admission, i.e., if hypoglycemia was an in-hospital complication it was no longer counted as an exposure, and those patients were considered not to have had hypoglycemia. Last, for exploratory purposes in the original study cohort only, we conducted stratified analyses and compared the strength of association between mortality and severe hypoglycemia within A1C strata in the “normal” range (<6% [<42 mmol/mol]) versus strata representing higher levels of A1C. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and Stata SE 11 (StataCorp, LP, College Station, TX) software.

RESULTS

The final cohort included 85,810 patients. Their mean age was 75 years (SD 6.6), half were women, half had diabetes, and one-third had A1C values <6% (42 mmol/mol). Most (63%) patients had an index eGFR of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or more. Over a median follow-up of 4 years (interquartile range [IQR] 2.5–4.9 years), 440 (0.5%) patients suffered at least one episode of severe hypoglycemia associated with hospitalization. Of these episodes, 92 (21%) were the primary reason for admission, 189 (43%) were secondary diagnoses, and only 159 (36%) were considered in-hospital complications. The rate of hospitalized hypoglycemia in the study cohort was 1.5 per 1,000 person-years. Of note, only 23 of 440 (5%) patients with hospitalized hypoglycemia had another episode during follow-up. Table 1 presents patient characteristics according to the presence or absence of hospitalized hypoglycemia; in general, those with an episode of hypoglycemia were older, were more likely to have diabetes and other comorbidities, and had lower eGFR and poorer glycemic control than those who never suffered a severe hypoglycemic event. Hypoglycemic patients were also more likely to have had a previous episode of hospitalized hypoglycemia and to use insulin, as compared with patients who never suffered severe hypoglycemia (Table 1).

Hospitalized hypoglycemia and all-cause mortality

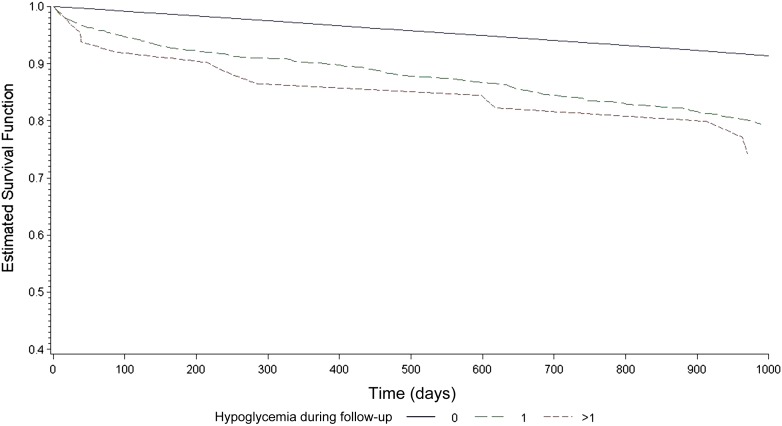

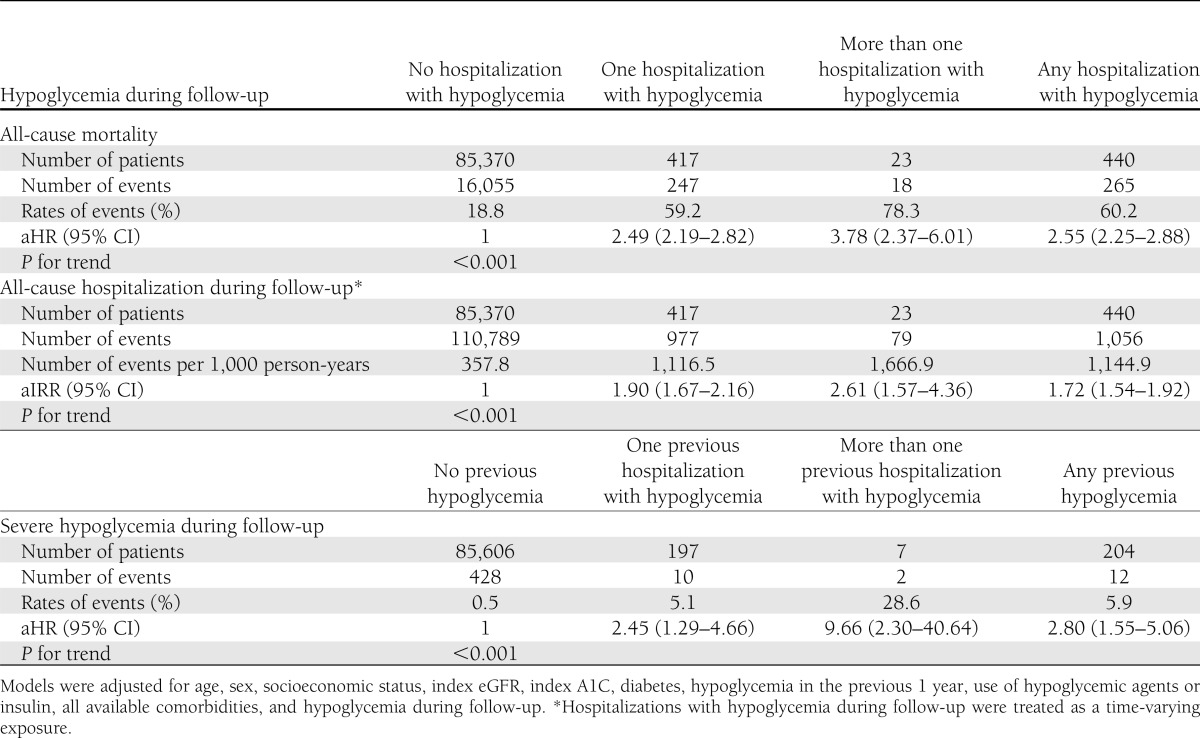

Over the study period, 16,320 patients in the cohort died. Those who had at least one episode of severe hypoglycemia associated with hospitalization were three times more likely to die during subsequent follow-up compared with those who never had hypoglycemia, and this association remained strong and statistically significant in adjusted analyses: 265 of 440 (60%) mortality for those with hypoglycemia vs. 16,055 of 85,370 (19%) for those without, adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) 2.55 (95% CI 2.25–2.88; P < 0.001) (Table 2). The median time between an episode of hospitalized hypoglycemia and death was 401 days (IQR 76–873). There was evidence of an independent and graded dose-response association with respect to hospitalized hypoglycemia: 19% mortality for no hypoglycemia (aHR 1.0) vs. 59% mortality for one episode (aHR 2.49 [2.19–2.82]) vs. 78% mortality for more than one episode (aHR 3.78 [2.37–6.01]; P < 0.001 for trend) (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Adjusted risk of adverse events, by presence or absence of severe (hospitalized) hypoglycemia and the frequency of hypoglycemia episodes

Figure 1.

Adjusted survival curves for all-cause mortality according to the frequency of hospitalized hypoglycemia (none vs. one vs. more than one episode).

Hospitalized hypoglycemia and all-cause hospitalization

Over the 4-year study period, there were 111,845 hospitalizations, and 43,177 (50%) of the cohort was hospitalized at least once. The rate of subsequent hospitalization for patients who had at least one episode of hospitalized hypoglycemia was triple the rate for those who never had hypoglycemia, and this association remained strong and statistically significant in adjusted analyses: 1,145 hospitalizations per 1,000 person-years for those with hypoglycemia vs. 358 hospitalizations per 1,000 person-years for those without (adjusted incidence rate ratio [aIRR] 1.72 [95% CI 1.54–1.92]; P < 0.001) (Table 2). The median time between the episode of hypoglycemia and subsequent hospitalization was 120 days (IQR 38–350). There was again a significant dose-response association: 358 hospitalizations per 1,000 person-years in patients with no hypoglycemia (aIRR 1.0) vs. 1,117 hospitalizations per 1,000 person-years in those with one episode (aIRR 1.90 [1.67–2.16]) vs. 1,667 hospitalizations per 1,000 person-years for those with more than one episode (aIRR 2.61 [1.57–4.36]; P < 0.001 for trend).

Hospitalized hypoglycemia and recurrent hospitalized hypoglycemia

There were 41 hospitalizations associated with recurrent (i.e., repeat), severe hypoglycemia over the course of the study. In adjusted analyses, the hazard of hospitalization with hypoglycemia for patients who had already suffered an incident episode of severe hypoglycemia was significantly greater than the rate for those who had never had hypoglycemia (aHR 2.80 [95% CI 1.55–5.06]; P < 0.001) (Table 2). The median time between the initial episode of hospitalized hypoglycemia and recurrent hospitalization with hypoglycemia was 359 days (IQR 153–623). There was a steep dose-response association when comparing no prior hypoglycemia (aHR 1.0) vs. one episode (aHR 2.45 [1.29–4.66]) vs. more than one prior episode (aHR 9.66 [2.30–40.64]; P < 0.001 for trend).

Sensitivity and exploratory analyses

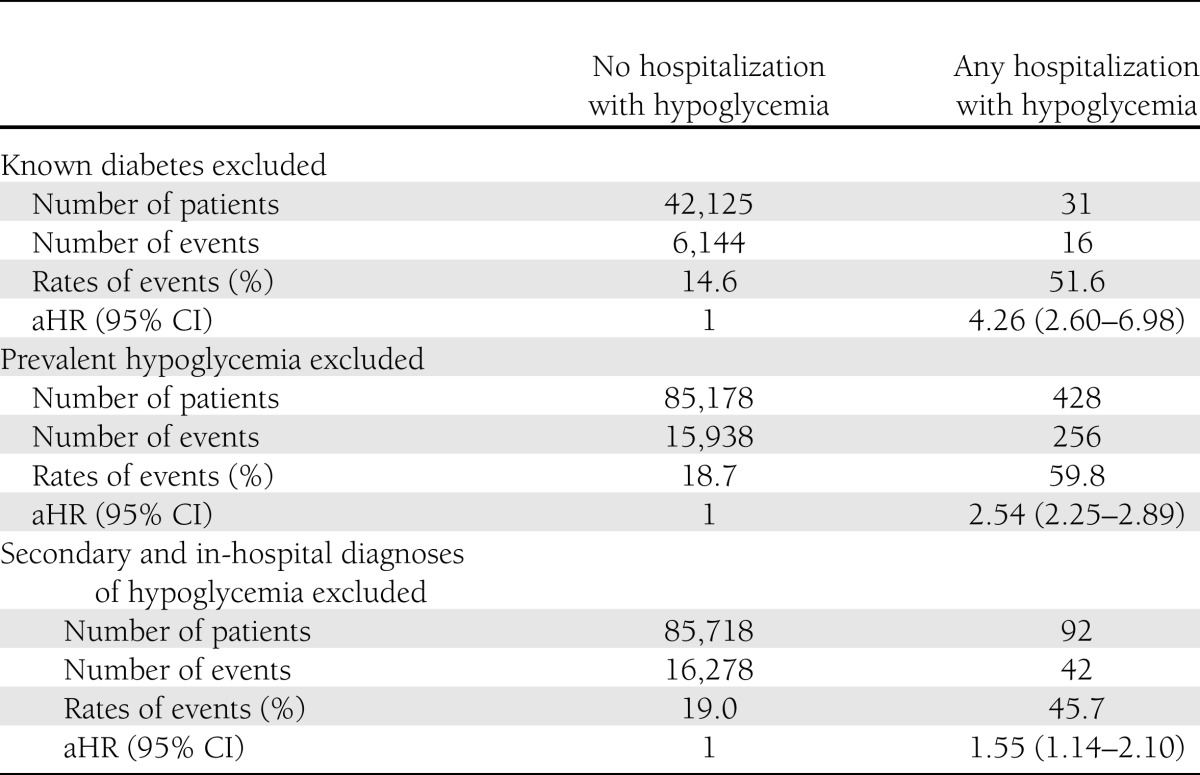

First, excluding 43,494 patients with diabetes from the original cohort defined using administrative data resulted in an even stronger independent association between hospitalized hypoglycemia and all-cause mortality: aHR 4.26 (95% CI 2.60–6.98) for those without diabetes at study entry vs. 2.46 (2.17–2.80) for those with diabetes (P = 0.032 for difference) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sensitivity and exploratory analyses for examining the association between hospitalized hypoglycemia and all-cause mortality

Second, excluding the 204 patients who had had one or more episodes of prevalent hospitalized hypoglycemia in the 1 year prior to study entry from the original cohort did not materially affect the strength or significance of the association between hypoglycemia and mortality: aHR 2.54 when these patients were excluded vs. 2.55 in the main analysis (P > 0.5 for difference) (Table 3).

Third, redefining the main exposure variable of hospitalized hypoglycemia to be present only if it was the primary reason for admission (n = 92 patients instead of the original 440 patients) led to some attenuation of the association, although it remained statistically significant (aHR 1.55 [95% CI 1.14–2.10]; P < 0.001) (Table 3).

Fourth, again redefining the main exposure variable of hospitalized hypoglycemia to be present only if it was the primary or secondary diagnosis but excluding in-hospital complications (n = 281 patients instead of the original 440 patients) led to attenuation of the association, although it still remained statistically significant (aHR 2.24 [95% CI 1.92–2.62]; P < 0.001).

Last, in stratified analyses, the association between hospitalized hypoglycemia and mortality was significantly stronger among the 29,716 patients with A1C <6% (<42 mmol/mol) compared with the 55,654 patients with higher A1C: aHR 3.89 (95% CI 2.85–5.31) for those with A1C <6% (<42 mmol/mol) vs. 2.19 (1.85–2.59) for those with A1C ≥6% (≥42 mmol/mol; P < 0.001 for difference).

CONCLUSIONS

In a population-based cohort of >80,000 older patients with and without diabetes, we found that severe hypoglycemia (i.e., associated with hospitalization) was relatively uncommon and occurred in ∼0.5% of the population over 4 years, about one episode per 1,000 person-years. Although uncommon, hospitalized hypoglycemia was associated with a grave prognosis, and fully 60% of those who suffered an episode died during follow-up. In adjusted analyses, hospitalized hypoglycemia was associated with a 2.6-fold relative increase in mortality, a 72% increase in subsequent all-cause hospitalizations, and a 180% increase in suffering another episode of hypoglycemia requiring hospitalization. These associations were independent of diabetes or its treatments, were observed for three clinically relevant end points, and exhibited a strong and consistent dose-response relation.

Much of the debate regarding the association between hypoglycemia and mortality has been related to its mechanism and not its prognostic impact, and it has tended to center on issues related to the hypoglycemic consequences of early and intensive glycemic control in those with diabetes or prediabetes (3,6,7). Our finding that the risk of death after hospitalization with hypoglycemia was more pronounced among those with normal or lower A1C at baseline and those without a diagnosis of diabetes may be potentially quite relevant to this ongoing discussion.

Mortality has previously been directly linked to single episodes of documented severe hypoglycemia in type 1 and type 2 diabetes and in critically ill patients (1–3), and mortality has also been associated with having multiple episodes of hypoglycemia via mechanisms related to autonomic failure (2,3,23). That said, in aggregate, most analyses conducted to date suggest that severe hypoglycemia is probably a marker of vulnerability and high-risk status rather than a direct cause of death (6,7,14–16). Our findings strongly support this notion, as the median interval between an episode of hospitalized hypoglycemia and death was >1 year, and adjustment for age, socioeconomic status, and comorbidities attenuated (but did not eliminate) the association.

Despite its strengths, our study has several limitations. First, we were unable to distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and our diagnoses of diabetes were based on administrative data rather than clinical information such as a registry. Second, because of the need to include diabetes prescription treatment data, we could not study those younger than 65 years of age, and thus whether these findings apply to younger adults is uncertain. Third, although we have prescription drug data for diabetes treatments, we did not capture dose/duration/adherence information, and we did not account for nondiabetes medications previously reported to have caused hypoglycemia as a documented side effect, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, indomethacin, lithium, or quinine sulfate (2). Fourth, although we have measures of eGFR and glycemic control, we do not have any indicators of weight, weight loss, or nutritional status, all of which would likely affect vulnerability to hypoglycemia, particularly among those without diabetes (1). Fifth, in terms of mechanistic exploration of our findings, we do not know the cause of death and had limited information about nonfatal events (such as myocardial infarction, stroke, motor vehicle accident, or falls). It was also not possible to determine if the severe hypoglycemia in our study was “spontaneous” or “iatrogenic.” Sixth, our definitions of exposure were based on physician diagnoses and discharge data, and so we did not have access to glucose measurements at the time of the presumably clinically symptomatic and recognized hypoglycemic episode. Fortunately, our results were robust to whether we considered “any” diagnosis, primary and secondary diagnoses, or only primary most-responsible diagnosis. Seventh, our results were based on those participants who had serum creatinine measured as part of clinical care. However, since assessment of kidney function is a recommended part of the care of patients with, or at risk for, diabetes and because all Alberta residents are entitled to free medical care, we do not believe that this is likely to have affected our conclusions. Last, we could not capture less-severe episodes of hypoglycemia (i.e., that did not require hospitalization but might have still required third-party assistance of some type, such as an emergency department visit), and so we have systematically underestimated rates of hypoglycemia, hypoglycemic unawareness, and the possibility that hypoglycemia-associated autonomic failure might contribute to mortality (3,23).

Although we observed that hospitalized hypoglycemia was relatively uncommon, we found that it carried a grave prognosis with respect to morbidity and mortality. Our work supports the notion that hypoglycemia is most likely an easy to measure marker of severe vulnerability (based on comorbidities or unrecognized frailty) to adverse events such as mortality, and that patients who have suffered an episode of severe hypoglycemia should be reviewed carefully and followed up regularly in the community by their health care providers to try and prevent or at least ameliorate such major potential adverse events.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an interdisciplinary team grant to the Interdisciplinary Chronic Disease Collaboration from the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. S.R.M. is a Health Scholar of Alberta Innovates–Health Solutions and the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research and holds an Endowed Chair in Patient Health Management from the Faculties of Medicine and Dentistry and Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Alberta. M.T. is supported by a Population Health Scholar award from Alberta Innovates–Health Solutions and by a Government of Canada Research Chair in the optimal care of people with chronic kidney disease. S.R.M., B.R.H., B.J.M., and M.T. are all supported by a joint initiative between Alberta Health and the University of Alberta and University of Calgary.

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

S.R.M. conceived and designed the study, drafted the manuscript, and performed statistical analysis. B.R.H. acquired data, obtained funding, and provided administrative, technical, and material support. M.L. drafted the manuscript and performed statistical analysis. B.J.M. acquired data, obtained funding, and provided administrative, technical, and material support. M.T. acquired data, drafted the manuscript, performed statistical analysis, obtained funding, and supervised the study. All authors, including K.M., analyzed and interpreted data and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. M.T. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Service FJ. Hypoglycemic disorders. N Engl J Med 1995;332:1144–1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cryer PE, Axelrod L, Grossman AB, et al. Endocrine Society Evaluation and management of adult hypoglycemic disorders: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:709–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cryer PE. Death during intensive glycemic therapy of diabetes: mechanisms and implications. Am J Med 2011;124:993–996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei M, Gibbons LW, Mitchell TL, Kampert JB, Stern MP, Blair SN. Low fasting plasma glucose level as a predictor of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. Circulation 2000;101:2047–2052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nirantharakumar K, Marshall T, Hodson J, et al. Hypoglycemia in non-diabetic in-patients: clinical or criminal? PLoS ONE 2012;7:e40384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonds DE, Miller ME, Bergenstal RM, et al. The association between symptomatic, severe hypoglycaemia and mortality in type 2 diabetes: retrospective epidemiological analysis of the ACCORD study. BMJ 2010;340:b4909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zoungas S, Patel A, Chalmers J, et al. ADVANCE Collaborative Group Severe hypoglycemia and risks of vascular events and death. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1410–1418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.UK Hypoglycaemia Study Group Risk of hypoglycaemia in types 1 and 2 diabetes: effects of treatment modalities and their duration. Diabetologia 2007;50:1140–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCoy RG, Van Houten HK, Ziegenfuss JY, Shah ND, Wermers RA, Smith SA. Increased mortality of patients with diabetes reporting severe hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care 2012;35:1897–1901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitmer RA, Karter AJ, Yaffe K, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Selby JV. Hypoglycemic episodes and risk of dementia in older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 2009;301:1565–1572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ginde AA, Espinola JA, Camargo CA., Jr Trends and disparities in U.S. emergency department visits for hypoglycemia, 1993-2005. Diabetes Care 2008;31:511–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao Y, Campbell CR, Fonseca V, Shi L. Impact of hypoglycemia associated with antihyperglycemic medications on vascular risks in veterans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012;35:1126–1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finfer S, Liu B, Chittock DR, et al. NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators Hypoglycemia and risk of death in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1108–1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kosiborod M, Inzucchi SE, Goyal A, et al. Relationship between spontaneous and iatrogenic hypoglycemia and mortality in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 2009;301:1556–1564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gamble JM, Eurich DT, Marrie TJ, Majumdar SR. Admission hypoglycemia and increased mortality in patients hospitalized with pneumonia. Am J Med 2010;123:e11–e16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boucai L, Southern WN, Zonszein J. Hypoglycemia-associated mortality is not drug-associated but linked to comorbidities. Am J Med 2011;124:1028–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hemmelgarn BR, Clement F, Manns BJ, et al. Overview of the Alberta Kidney Disease Network. BMC Nephrol 2009;10:30–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tonelli M, Manns B, Culleton B, et al. Alberta Kidney Disease Network Association between proximity to the attending nephrologist and mortality among patients receiving hemodialysis. CMAJ 2007;177:1039–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen G, Khan N, Walker R, Quan H. Validating ICD coding algorithms for diabetes mellitus from administrative data. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;89:189–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005;43:1130–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ray WA. Evaluating medication effects outside of clinical trials: new-user designs. Am J Epidemiol 2003;158:915–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suissa S. Immortal time bias in pharmaco-epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:492–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cryer PE. Mechanisms of hypoglycemia-associated autonomic failure and its component syndromes in diabetes. Diabetes 2005;54:3592–3601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]