Abstract

Background

As interventions are not yet successful in substantially improving physical activity levels of low socioeconomic status groups in the Netherlands, it is a challenge to undertake more effective interventions. Participatory community-based physical activity interventions such as Communities on the Move (CoM) seem promising. Evaluating their effectiveness, however, calls for appropriate evaluation approaches.

Objective

This paper provides the conceptual model for the development of a context-sensitive monitoring and evaluation approach in order to (1) measure the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of CoM, and (2) develop an evaluation design enabling the identification of underlying mechanisms which explain what works and why in community-based physical activity programs.

Methods

A cohort design is proposed, based on multiple cases, measuring impact, processes, and changes at each of the distinguished levels. The methods described in this paper will evaluate both short- and long-term effects, costs, and benefits of CoM.

Results

Testing of the proposed model began in October 2012 and is on-going.

Conclusions

The design offers a valid research strategy for evaluating the effectiveness of community-based physical activity programs. Internal validity is guaranteed by the use of several verification techniques such as triangulation. The multiple case studies at the program and community levels enhance external validity.

Keywords: community-based physical activity program, cost-effectiveness, low socioeconomic status groups, health promotion, evaluation design

Introduction

Background

Physical inactivity is one of the four core risk factors for non-communicable diseases such as diabetes type 2 and cardiovascular diseases. It has been identified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality in 2012, causing an estimated 3.2 million deaths globally [1].

In the Netherlands, the Dutch Healthy Physical Activity Guidelines (NNGB) have been in use as a standard for monitoring physical activity behavior at population level since 1998. These guidelines set the norm for healthy daily physical activity for adults at a minimum of 30 minutes of moderate activity at least 5 days a week [2]. Research shows that physical activity levels of the Dutch adult population are rising, from 44% in 2000 to 62% in 2009 meeting the guidelines for healthy physical activity [3]. Adults spend on average 178 minutes per day in physical activity. Work, school, and domestic activities are the most important sources of physical activity.

Not all population strata, however, show this upward trend. The engagement of low socioeconomic status (SES) groups in sports and physical activity in the Netherlands remains lower than in high SES groups [4], despite various policies promoting community-based health and physical activity programs at the national, regional, and local level [5]. The neighbourhood is recognized as a setting in which to promote health and physical activity and to strengthen people’s responsibility for their own health and social participation [5-7].

As interventions have not yet been successful in substantially improving physical activity levels of low SES groups, it is a challenge to undertake more effective interventions [8]. In line with national policy objectives, the Netherlands Institute for Sports and Physical Activity (NISB) developed and disseminated a community-based program enhancing physical activity in inactive low SES target groups: the Communities on the Move (CoM) approach. The aim of CoM is to enhance physical activity levels of low SES groups, in order to contribute to social participation, quality of life, and life satisfaction of individual participants. Since 2003, CoM has been carried out by a variety of user organizations in 37 municipalities, reaching over 100 groups. Preliminary results of the program are promising. An expert panel of the Dutch Centre of Healthy Living has approved CoM as theoretically underpinned [9], but its effectiveness and cost-effectiveness have not yet been researched comprehensively.

Community-based interventions like CoM are grounded in both individual and community level theories [9,10], calling for appropriate designs to evaluate them at different impact levels [11]. To our knowledge, community-based physical activity programs have not yet been assessed comprehensively on both process and indicators for effectiveness at multiple levels. The aim of this paper is to provide the conceptual model for the development of a context-sensitive monitoring and evaluation approach in order to (1) measure the effectiveness, including the cost-effectiveness, of CoM, and (2) develop an evaluation design enabling the identification of underlying mechanisms that explain what works and why in community-based physical activity programs. The proposed research design is based on insights derived from the authors’ experiences in community-based health promotion programs [12-14].

The Communities on the Move Approach

CoM targets inactive, low SES groups. CoM is a principle-based approach, enabling community-based physical activity interventions to be tailored to the needs and demands of target groups within specific local contexts. The objective is to identify, assess, and mobilize available resources for physical activity within the target group and their community. This requires a participatory approach in program development and implementation, involving different stakeholders including the target population in all stages of program planning, implementation, and evaluation [15,16]. CoM is linked to the assets for health concept [17]—a health asset being any factor that enhances the ability of individuals, communities, populations, and/or social systems to improve or maintain health and well-being. The concept includes a salutogenic perspective on health, focusing on positive health outcomes [18,19].

The key principles of CoM, identified and used in a 4-year pilot phase (2003–2007), at the program and community levels are: intersectoral collaboration, coordinated action for sustainability, and active participation of local stakeholders (organizations and community representatives). The key principles at the group and individual levels are: a social network approach, active participation of participants in program development, enjoyment, group bonding, and creating supportive environments. Phase 1 of a CoM program starts with problem definition, based on community assessments identifying stakeholders, physical activity needs, and assets. Phase 2 is planning and development of program activities with local stakeholders, setting goals, and defining actions within contextual boundaries. Phase 3, the actual implementation phase, is a stepwise approach, starting with activities for recruitment. First, the participants are recruited by accessing community groups and mobilizing their social networks, where a community group may be women visiting a mosque, for instance. The second step is defining and implementing the action program using group members’ input to tailor physical activities to their needs. The third step is consolidation. Group members practice what they have learned and actively involve their social and physical environments in order to sustain their behavior change. Phase 4 of CoM is program evaluation to document impact and lessons learned for further dissemination. Table 1 is a schematic representation of a local CoM program.

Table 1.

Principle-based CoM approach in local practice.

|

|

Phase 1 Problem identification |

Phase 2 Program development |

|

Phase 3 Program implementation |

|

Phase 4 Evaluation |

||

|

|

|

|

Recruitment | Action | Consolidation |

|

||

| Program organization | ||||||||

|

|

Intersectoral

collaboration |

assessment community needs and assets |

setting goals | program coordination and monitoring |

program coordination and monitoring |

program coordination and monitoring |

formation new groups | |

|

|

|

stakeholder involvement |

program development |

communication | communication | communication |

|

|

|

|

Program

sustainability |

assessment policy goals | organizing resources |

introduction activity program |

physical activities program | physical activities program |

|

|

|

|

|

|

capacity building | demonstration lessons | theme sessions |

|

|

|

| Community | ||||||||

|

|

Active participation | identification target groups |

identification key persons |

|

|

|

formation new groups | |

|

|

Social network |

|

|

mobilizing participants |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Create supportive

environments |

|

|

|

|

involving social and physical environment |

|

|

| Group | ||||||||

|

|

Group bonding |

|

|

getting acquainted |

social learning | group cohesion | sustained group activities |

|

|

|

Active participation |

|

|

program attendance |

program attendance |

group initiatives |

|

|

|

|

Create supportive

environments |

|

|

|

|

involving social and physical environment |

|

|

| Individual | ||||||||

|

|

Social network |

|

|

participants acquainted |

|

involving social and physical environment |

sustained physical activity behavior | |

|

|

Active participation |

|

|

assessment physical activity needs and ambitions |

competence development (attitude, knowledge, skills) |

competence development |

|

|

|

|

Pleasure |

|

|

exploring which physical activity are liked | learning to enjoy physical activity | competence and confidence development |

|

|

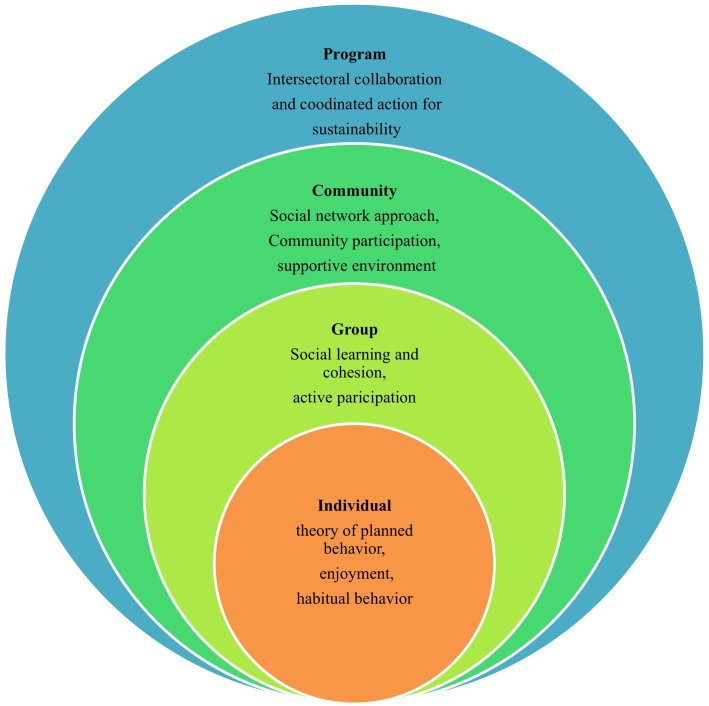

Theories to develop and implement CoM use an ecological perspective on human health. The ecological perspective emphasizes the interaction between factors within and across the different levels [20]. To address the reciprocity of human interactions with their social and physical environment, CoM advocates actions at multiple levels, whereas each level builds on different theoretical frameworks (Figure 1). At the individual level, CoM aims to initiate and sustain change in physical activity behavior, building on the concepts of the theory of planned behavior (TPB). These concepts include behavioral intention, attitude, subjective norms and social influence, and self-efficacy [21]. CoM stimulates adherence to physical exercise and the development of habitual behavior through enjoyment [22-24]. At the group level, social learning processes and active participation, based on concepts of social cognitive theory (SCT), are used to support sustained behavioral change [20,25]. At the community level, CoM is based on the social network approach, community participation, and the notion of supportive environments. Social networks contribute to health [26] and effectively support physical activity behavior [27]. Community participation fosters higher levels of motivation and determines effectiveness [12]. At the program level, CoM is underpinned by theories on intersectoral collaboration and coordinated action [13], addressing stakeholder involvement and community ownership. Intersectoral collaboration strengthens the development and contextualization of the intervention by assessing assets and resources of various stakeholders and translates them into customised program activities. Intersectoral collaboration also contributes to the sustainable implementation of CoM.

Figure 1.

Theoretical underpinning of CoM.

Evaluation Objectives

CoM’s evaluation approach aims to (1) assess the effectiveness of CoM at different impact levels (individual, group, program, and community), (2) identify underlying mechanisms to explain the context sensitivity of program development and implementation, and (3) assess the cost-effectiveness of CoM. This paper will address the following research questions:

Which effects can be documented with respect to physical activity behavior, health, quality of life, and life satisfaction?

Which mechanisms explain the successes and failures of CoM in low SES groups and how can these be addressed?

How can results be interpreted in terms of costs and benefits and what combination of economic evaluation methods and tools is most appropriate to evaluate a community-based program on cost-effectiveness?

Methods

Study Design

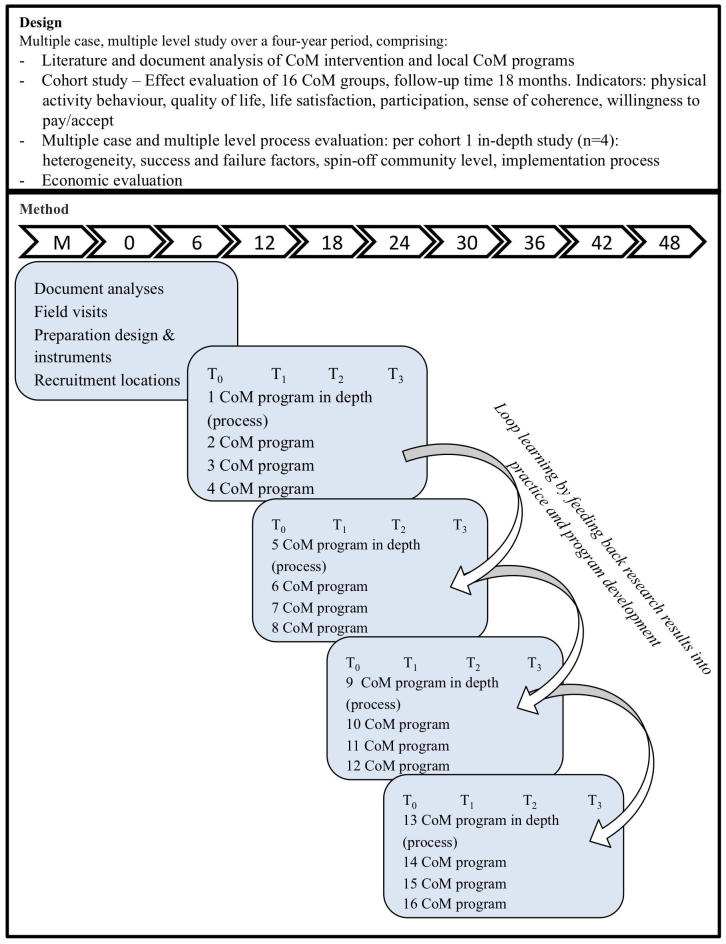

To measure the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of CoM, our study combines a cohort analysis based on multiple cases, and a process evaluation and action research, measuring processes and changes at each of the 4 defined impact levels at multiple points in time (Figure 2). The study includes 16 groups of CoM programs in different municipalities, in 4 cohorts of 4 groups. Data will be collected through standardized questionnaires, open interviews, document analysis, interactive procedures, and focus groups. Four CoM programs (one case from each cohort) will be studied in depth. The advantage of a cohort analysis with cohorts starting successively over a course of 2.5 years is that multiple intermediate outcomes can be studied simultaneously over a period of time. It allows control for possible history and maturity effects, and as such it offers a valid alternative for a randomized controlled trial (RCT) design. RCT designs are considered less appropriate to assess the cost and effectiveness of CoM at multiple levels and to identify underlying mechanisms explaining success and failures for the following reasons [14,28]:

Figure 2.

Evaluation design of CoM.

RCT designs focus on behavior change at individual and community population level, not taking into consideration conditions for change related to social, cultural, and organizational factors [14,29].

Applying the RCT design is difficult because of the absence of appropriate ways to define control groups in real life settings. Community-based physical activity promotion settings are generally open to the public at large, and people living in the control areas have access to the activities as well, hence, participants cannot be assigned randomly. Initial physical activity motivations for members of the community may also be different, making randomization difficult [14,28].

There are limitations in the ability of RCT designs to grasp the importance of interactions between the individual and his or her social and physical environment [30,31].

A mixed method design is therefore required to gain insight into the effectiveness of CoM programs at all 4 defined impact levels and to understand the process, the interactions and the quality of interactions needed for success [14,30]. An action approach enables researchers and local CoM stakeholders, including CoM participants, to apply and benefit from loop learning [12,32]. Learning loops are applicable to the CoM programs and to the overall learning processes of CoM and this research project. For local CoM programs, single-loop learning results in an improved local program. Double-loop learning results in adaptation of the organization of the program. The learning outcomes in the first four CoM programs can be used in the next four CoM programs and so on. As a consequence, during the research, CoM quality will be improved.

Study Population

To assess outcomes at the individual and group levels, inclusion criteria for the study participants in CoM programs are inactivity, adults not meeting the NNGB, and low socioeconomic status (income, education, and employment conditions). In each CoM program, one or more groups will be included in the study for convenience sampling. During the study, 16 groups will be studied, each group consisting on average of 15 participants. Consequently, a total of 240 participants will be included. Data will be collected at 4 time-points: at the start of a local program (T0), at 6 months (T1), at 12 months (T2), and at 18 months (T3).

At program and community levels, on-going CoM programs will be included, based on existing partnerships between NISB and implementing organizations (purposive sampling). The study population consists of local stakeholders such as user organizations and networks in place, the disseminating organization (NISB), and community representatives.

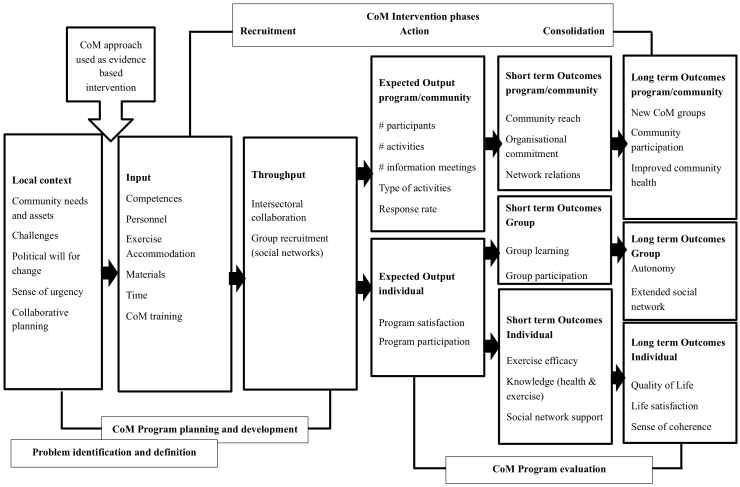

Logic Model

Figure 3 illustrates the logic model for impact evaluation of CoM, based on the literature on community-based evaluation approaches [33] as well as dissemination studies of evidence-based interventions [34,35]. The hypothesis is that a community-based participatory approach to developing and implementing physical activity programs is effective in enhancing physical activity levels in low SES target groups and results in increases in quality of life, life satisfaction, and community participation.

Figure 3.

Logic model for evaluation effectiveness CoM.

The framework was developed based on the perspectives of the local program initiators and the community. Local program initiators seek the evidence base, developed in CoM and disseminated by NISB, whereas community-based approaches follow non-linear pathways of development and implementation [33]. This calls for process evaluation, addressing intersectoral collaboration, capacity building and network development, as well as identification of intermediate measures to be monitored at the different impact levels. Short term output is defined in terms of concrete activities, reach, and program satisfaction. Short term outcome indicators are defined in terms of measurable impact, such as increase in physical activity and knowledge, and the use of qualitative data (group learning) to understand outcomes. Long term outcome indicators are defined to measure broader outcomes and monitor local change.

Impact Assessment

To assess effects with respect to physical activity behavior, quality of life, and life satisfaction at the individual level, a standardized questionnaire will be used to measure quantitative short- and long-term outcomes (Table 2). The questionnaire has been developed using concepts from the underlying theories of TPB, in addition to questions related to sports and physical activity behavior. Data on socioeconomic indicators will be collected (ie, age, income, education, employment, living conditions), in accordance with standardized questions in the Local and National Monitor Public Health in the Netherlands [36].

Table 2.

Overview of variables and methods of data collection.

| Level | Variables | Questionnaires | Document analysis |

Interview | Focus group | Instruments | |||

|

|

|

T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 |

|

|

|

|

| Individual |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Age, gender, income, education, ethnic background | x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Questionnaire |

|

|

Quality of life | x | x | x | x |

|

|

|

EQ-VAS |

|

|

Life satisfaction | x | x | x | x |

|

|

|

Cantril’s ladder |

|

|

Physical activity and health behavior | x | x | x | x |

|

|

x | Questionnaire |

|

|

BMI | x | x | x | x |

|

|

|

Questionnaire |

|

|

Sense of Coherence | x |

|

|

x |

|

|

|

SOC-13 scale |

|

|

Enjoyment | x | x | x | x |

|

|

x | PACES scale |

|

|

Willingness to pay | x | x | x |

|

|

|

|

Questionnaire |

|

|

Personal goals | x | x | x | x |

|

|

x | Questionnaire |

| Group |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Social support | x | x |

|

x |

|

|

x | Questionnaire |

|

|

Participation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

x | Timeline Pretty’s ladder |

| Program |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Organization and collaboration |

|

|

|

|

x | x | x | Coordinated action checklist |

|

|

Program participation | x | x |

|

|

|

x | x | Pretty’s ladder |

|

|

Support and training |

|

|

|

|

x | x | x |

|

|

|

Competences |

|

|

|

|

|

x | x |

|

|

|

Diffusion |

|

x |

|

|

x | x | x |

|

|

|

Cost per QALY | x | x | x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cost-effectiveness |

|

x |

|

|

x |

|

|

QALY |

| Community |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spin-off: new programs and community participation |

|

|

x | x | x | x | x | RE-AIM framework |

To measure physical activity, the validated Short QUestionnaire to ASses Health enhancing physical activity (SQUASH) will be used [37]. Correlations for reproducibility of the separate questions vary between 0.44 and 0.96. Spearman’s correlation coefficient between CSA readings and the total activity score was 0.45 (95% CI 0.17-0.66) [38]. The SQUASH questionnaire was used as it generates data that can be compared with national and regional data. The Dutch trend analyses for physical activity behavior over the past 2 decades were based on the SQUASH, offering a vast body of reference data for our study [3].

In this study we will explore the use of objective measures for physical activity, such as walking tests or accelerometers [39,40]. These objective measurements, however, generally require additional data such as generated by SQUASH, to be able to interpret outcomes on physical activity behaviors and the development of habitual physical activity behavior. Some challenges remain with the use of objective physical activity measures. First, validity and reliability can be questionable, for example, when these measures are used with user groups suffering from chronic diseases [41]. Second, organizational efforts and costs are practical issues related to implementation that must be considered [40].

To measure personal goals on health and physical activity behavior, a number of personal features will be documented (eg, demographics, BMI). To measure life satisfaction, Cantril’s Self-Anchoring Ladder for Life Satisfaction will be used [42]. To measure the ability to cope with stressors, the validated 13-item Sense of Coherence (SOC) questionnaire will be used [43]. Cronbach alpha values in 127 studies using SOC-13 ranged from 0.70 to 0.92 [44]. To measure enjoyment, the 9-item short version of Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES) will be used [45,46].

To assess mechanisms explaining successes and failures of CoM in low SES groups and how these can be addressed, data will be collected at the group and program level through interviews, focus groups, and document analysis (Table 2). A combination of action research and realism evaluation will be used. Action research is important because it has both an action function, which supports the progress of the intervention, and an evaluation function, which seeks to monitor and ascertain processes and outcomes of interventions [47]. Realism evaluation facilitates the study of the interactions between context and program mechanisms determining the outcomes [48]. To assess CoM’s context-based information, each of the CoM programs will include an interview with the program coordinator and the two focus groups—the local stakeholders and the CoM participants. To measure effectiveness at the program level, we will incorporate the factors for achieving and sustaining participation and collaboration [49], the coordinated action checklist [50], and Pretty’s participation ladder [25]. The RE-AIM dimensions (ie, reach, effectiveness-adoption, implementation, and maintenance) will serve as the framework to measure spin-offs and highlight areas that require special attention with respect to sustainability [51].

Economic Evaluation of CoM

To assess how results can be interpreted in terms of costs and benefits and what combination of economic evaluation tools is most appropriate to evaluate a community-based program on cost effectiveness, results from the cohort analysis, process evaluation, and action research at all levels discerned will be used (Table 2). The study perspective in evaluating CoM’s cost-effectiveness will be the societal perspective. Data will be collected about health-related quality of life in relation to the physical activity program and its program costs over a time frame of 18 months. To measure health-related quality of life, the Dutch EuroQoL (quality of life) scale (EQ-5D-3L) and the EQ visual analogue scale will be used. The EuroQoL scale is standardized, measuring non-disease specific health-related quality of life, in use for economic evaluation [52,53].

The methods used will include traditional measures such as cost utility, cost-benefit analysis, Quality Adjusted Life Year (QALY, expressed in euros per quality-adjusted life-year) gained, and willingness to pay or accept. We will also use instruments that measure changes in life satisfaction and sense of coherence (SoC).

At the individual level, the most usual means to measure changes in welfare are compensation tests. Compensation tests, such as willingness to pay, are measured based on monetary value [45]. Willingness to pay questions (for sport and physical activity) will be asked at distinctive points in time during the CoM program. To measure health gain, the QALY will be calculated by multiplying the amount of time in a particular health state by the quality of life during that time, summing over all time periods, standardized to a year [54].

A cost-effectiveness analysis at the program level will be performed by computing cost per QALY gained. At program level, costs such as salaries, training costs, and materials are summed up, and benefits are measured through the computation of QALY gained at various time-points, as described above. The outcomes of these computations will be compared with other relevant interventions. In all methods applied, assumptions used in the economic calculations and evaluation will be made explicit.

Analysis

Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative research data from interviews and focus group discussions will be audiotaped (with the interviewees’ permission), transcribed (intelligent verbatim style), and analyzed using Atlas.ti (version 7.0) to manage the data and guarantee transparency. Top-down as well as bottom-up coding will be used to provide for the analysis of differences in perspective of CoM participants, professionals, and scientists [55,56]. Case study data will be used to describe general mechanisms of failures and successes of the CoM program for various low SES groups.

Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative data will be analyzed with multivariate analysis techniques using the SPSS program. The quantitative variables at the individual level (Table 2) are to be tested for 4 independent variables (gender, age, ethnicity, and SES) using a multiple regression analysis with a significance level of .05 and a power of 0.80 for a medium effect size. This requires 84 participants for the study [57]. If there are several different groups (eg, ethnicity, SES) each with eight independent variables, 107 participants will be needed. Targeting 240 COM participants would satisfy these conditions.

Power Calculation

As the study design lacks control groups and consequently limits randomization, the assumption made in the power calculation is, that the CoM principles used are the same in each location. Effect sizes, therefore, can be calculated based on the overall population included in CoM programs.

The power calculation of the effectiveness of the CoM program is based on the variable physical activity, as the prime aim of the CoM program is to enhance physical activity in inactive, socially disadvantaged groups. Measures for change to be considered include: increase in the average number of minutes people are physically active, in the number of people meeting the Dutch Healthy Physical Activity Guidelines (NNGB), and in the number of people indicating that they are more physically active after participation in a CoM program.

Estimation of the effect size is based on an American systematic review study [27]. This review showed that the average time spent on physical activity increased by 35.4% (range 16.7-83.3%), based on 17 studies involving middle-aged adults. Dutch studies reviewing physical activity interventions gave no numerical information about effect sizes [58,59]. One intervention report showed an increase of 38% on average in the physical activity pattern. Based in these data, the estimated effect size for our study is set at an increase in physical activity of 35% in each group, roughly equivalent to 500 minutes a week.

A limitation of the proposed cohort design is the ability to correct for history or maturity effects, as the timeframe for data collection per cohort is restricted to 18 months with measurement intervals of only 6 months. To control for these effects, a comparison of cohorts will be conducted. Furthermore, comparisons will be made with existing population statistics for physical activity.

Management and Governance

Research activities will be developed and implemented in close collaboration with NISB to stimulate active knowledge exchange and co-creation of new knowledge. In this way, so-called context-sensitive evidence will be generated, which by its nature is relevant for intended users [60].

For the research project, a steering group consisting of representatives from Wageningen University and NISB will meet regularly. In addition, advisors from national and international organizations (eg, the Dutch Centre of Healthy Living, other universities, and community programs) will be involved for specific purposes, such as to review the developed questionnaires, to critically assess results of the interviews and focus groups, and to comment on drafts of scientific articles.

Intended Outputs

This study will result in recommendations for improving the health of low SES groups through physical activity. Further research results include:

An elaborated monitoring and evaluation design for participatory community health and physical activity promotion.

Assessment of CoM effectiveness and cost-effectiveness at the individual, program, and community levels.

The facilitation of wider implementation of CoM at both national and local level.

Results

The study began in October 2012 with data collection at both the individual (T0) and program levels. Baseline data was collected for the first cohort. At the program level, documentation is collected and interviews are conducted with local stakeholders. The study is on-going and funded by ZonMw, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (project number: 50-51505-98-103).

Discussion

Need for an Alternative Evaluation Approach

The need to elaborate an alternative evaluation approach to study the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a community-based physical activity program such as the CoM is evident. New indicators, methods, and tools are required in a real-world setting, comprising multiple levels. The design described in this paper offers a valid research strategy for effectiveness, combining cohort analysis, process evaluation, and action research within multiple cases (parallel investigations in different settings), addressing the different impact levels in a comprehensive way.

Credibility or internal validity is guaranteed by the use of several verification techniques such as triangulation, stakeholder checking, external auditing, and peer review [31,61]. Triangulation of data obtained by questionnaires, interviews, and focus groups elucidates why effects on physical activity behavior, health related quality of life and life satisfaction have occurred.

The multiple cases carried out at the program and community level (4 in-depth cases) will enhance external validity. The findings of the study will be context specific and specific to different low SES groups, but will also reveal generic mechanisms of change.

Value for Science, Practice, and Society

Conducting comparable studies in different situations will make it possible to draw conclusions about the quality of achievements and the processes and mechanisms in force in community-based projects, but also about the usefulness of (new) research techniques [31,47].

Practice will benefit from the research in various ways. Research activities will be part of the intervention, and stakeholders will participate in the development, implementation, and evaluation of research activities. Results will be fed back into the program immediately in order to undertake subsequent action. In addition, this research project will facilitate wider implementation of CoM.

Information on the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of community health promotion is highly relevant for policy makers to decide on the implementation of community-based approaches. In view of the increasing number of programs expected as a result of Dutch health policies aiming at self-mobilization and organization in neighbourhoods, this study will address the need to contribute to insight into context-sensitive intervention development targeting low SES people who are physically inactive, and how to monitor and evaluate these in a comprehensive way.

Acknowledgments

The study is funded by ZonMw, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (project number: 50-51505-98-103). NISB developed the Communities on the Move program and is the disseminating and collaborating agency with practice. We express our appreciation to the experts who peer reviewed the research design.

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- CoM

Communites on the Move approach

- EQ-VAS

standard visual analogue scale for rating health-related quality of life

- NISB

Netherlands Institute for Sports and Physical Activity

- NNGB

Dutch Healthy Physical Activity Guidelines

- PACES

Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale

- RE-AIM

reach, effectiveness-adoption, implementation, maintenance

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SES

socioeconomic status

- QALY

Quality Adjusted Life Year

- SOC

sense of coherence

- TPB

theory of planned behavior

- SCT

social cognitive theory

- SQUASH

Short QUestionnaire to ASses Health enhancing physical activity

- QoL

quality of life

- WHO

World Health Organization

- ZonMw

Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: MH was the first author of the manuscript and participated in the design of the study. AW, LV, JO, and MK designed the study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript and contributed to the drafting and revision of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.WHO. Geneva: WHO; 2012. [2013-05-17]. A comprehensive global monitoring framework and voluntary global targets for the prevention and control of NCDs http://www.who.int/nmh/events/2011/consultation_dec_2011/WHO_Discussion_Paper_FINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kemper HGC, Ooijendijk WTM, Stiggelbout M. Consensus over de Nederlandse norm voor gezond bewegen (NNGB) Tijdschr Soc Gezondheidsz. 2000;78:180–183. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hildebrandt VH, Chorus AMJ, Stubbe JH. TNO Innovation for Life. Leiden: TNO Innovation for Life; 2010. Trend report on physical activity and health 2008/2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wendel-Vos GC, Dutman AE, Verschuren WM, Ronckers ET, Ament A, van Assema P, van Ree J, Ruland EC, Schuit AJ. Lifestyle factors of a five-year community-intervention program: the Hartslag Limburg intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2009 Jul;37(1):50–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport. 2006. [2012-11-19]. Programma Samen voor Sport [Program Together for sports] http://www.rijksoverheid.nl/ministeries/vws/documenten-en-publicaties/notas/2006/05/31/programma-samen-voor-sport.html.

- 6.Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport. 2012. [2012-11-19]. Health close to people: national policy document on health http://www.government.nl/documents-and-publications/leaflets/2012/05/11/health-close-to-people.html.

- 7.Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport. 2007. [2012-11-19]. Social support act http://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/wet-maatschappelijke-ondersteuning-wmo.

- 8.Van der Lucht F, Polder J. Volksgezondheid toekomstverkenning [Public health perspectives] Bilthoven: RIVM National Institute for Public Health and the Environment; 2010. [2012-11-08]. Towards better health. The Dutch 2010 public health status and forecasts report (No. 270061011) http://www.vtv2010.nl/english-editions/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.RIVM National Institute for Public Health and the Environment. Centre for Healthy Living data base; 2009. [2012-11-08]. Communities in Beweging [Communities on the move] http://www.loketgezondleven.nl/i-database/interventies/c/12127/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Theorising interventions as events in systems. Am J Community Psychol. 2009 Jun;43(3-4):267–276. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9229-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dugdill L, Crone D, Murphy R. Physical activity and health promotion: evidence-based approaches to practice. Chichester, U.K: Blackwell; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagemakers A, Vaandrager L, Koelen MA, Saan H, Leeuwis C. Community health promotion: a framework to facilitate and evaluate supportive social environments for health. Eval Program Plann. 2010 Nov;33(4):428–435. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koelen MA, Vaandrager L, Wagemakers A. The healthy alliances (HALL) framework: Prerequisites for success. Fam Pract. 2012;29(Suppl. 1):132–138. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koelen MA, Vaandrager L, Colomér C. Health promotion research: dilemmas and challenges. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001 Apr;55(4):257–262. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.4.257. http://jech.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11238581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO global strategy on diet, physical activity and health. Geneva: WHO; 2008. [2013-01-28]. http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/strategy/eb11344/strategy_english_web.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolfenstetter SB, Schweikert B, John J. Programme costing of a physical activity programme in primary prevention: should the costs of health asset assessment and participatory programme development count? Adv Prev Med. 2012;2012:601–631. doi: 10.1155/2012/601631. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/601631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgan A, Ziglio E. Revitalising the evidence base for public health: an assets model. Promot Educ. 2007;Suppl 2:17–22. doi: 10.1177/10253823070140020701x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antonovsky A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promot Int. 1996 Mar 21;11(1):11–18. doi: 10.1093/heapro/11.1.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindström B, Eriksson M. The salutogenic approach to the making of HiAP/healthy public policy: illustrated by a case study. Glob Health Promot. 2009 Mar;16(1):17–28. doi: 10.1177/1757975908100747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rimer BK, Glanz K. US Dept of Health and Human Services. Nat Cancer Inst; 2005. [2013-05-30]. http://www.cancer.gov/PublishedContent/Files/cancertopics/cancerlibrary/TAAG3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heilbroner RL, Thurow LC, Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall; 1980. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henderson KA. A paradox of sport management and physical activity interventions. Sport Man Review. 2009 May;12(2):57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.smr.2008.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raedeke TD. The relationship between enjoyment and affective responses to exercise. J Appl Sport Psych. 2007 Feb 14;19(1):105–115. doi: 10.1080/10413200601113638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verplanken B, Melkevik O. Predicting habit: The case of physical exercise. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2008 Jan;9(1):15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2007.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pretty JN. Regenerating agriculture: policies and practice for sustainability and self-reliance. Washington, D.C: Joseph Henry Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawachi I, Berkman L. Social cohesion, social capital and health. In: Berkman L, Kawachi I, editors. Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kahn EB, Ramsey LT, Brownson RC, Heath GW, Howze EH, Powell KE, Stone EJ, Rajab MW, Corso P. The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity. A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2002 May;22(4 Suppl):73–107. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00434-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glasgow RE, Emmons KM. How can we increase translation of research into practice? Types of evidence needed. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:413–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green LW. Making research relevant: if it is an evidence-based practice, where's the practice-based evidence? Fam Pract. 2008 Dec;25(Suppl 1):i20–i24. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn055. http://fampra.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18794201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roussos ST, Fawcett SB. A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving community health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21:369–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowling A, Ebrahim S. Handbook of health research methods: investigation, measurement and analysis. Maidenhead, England: Open University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Argyris C. Single-loop and double-loop models in research on decision making. Adm Sci Q(3) 1976;21:363–375. http://mail.tku.edu.tw/myday/teaching/992/SMS/S/992SMS_T5_Paper_20110521_Single-Loop%20and%20Double-Loop%20Models%20in%20Research%20on%20Decision%20Making.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fawcett S, Schultz J. Supporting participatory evaluation using the community toolbox online documentation system. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health: from process to outcomes. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 419–424. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rabin BA, Brownson RC, Kerner JF, Glasgow RE. Methodologic challenges in disseminating evidence-based interventions to promote physical activity. Am J Prev Med. 2006 Oct;31(4 Suppl):S24–S34. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sallis JF, Owen N, Fotheringham MJ. Behavioral epidemiology: a systematic framework to classify phases of research on health promotion and disease prevention. Ann Behav Med. 2000;22(4):294–298. doi: 10.1007/BF02895665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.RIVM National Institute for Public Health and the Environment. 2005. [2013-04-26]. Nationale en Lokale gezondheidsmonitor [Local and National Health Monitor] https://www.monitorgezondheid.nl/

- 37.Ooijendijk W, Wendel-Vos W, De Vries S. TNO Innovation for Life. Leiden: TNO Innovation for Life; 2007. [2013-01-30]. Advies consensus vragenlijst sport en bewegen http://www.tno.nl/downloads/TNO-KvL_Rapport_Consensus_Vragenlijst_Sport_Bewegen.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wendel-Vos GC, Schuit AJ, Saris WH, Kromhout D. Reproducibility and relative validity of the short questionnaire to assess health-enhancing physical activity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003 Dec;56(12):1163–1169. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tudor-Locke C, Williams JE, Reis JP, Pluto D. Utility of pedometers for assessing physical activity: convergent validity. Sports Med. 2002;32(12):795–808. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200232120-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murphy SL. Review of physical activity measurement using accelerometers in older adults: considerations for research design and conduct. Prev Med. 2009 Feb;48(2):108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Solway S, Brooks D, Lacasse Y, Thomas S. A qualitative systematic overview of the measurement properties of functional walk tests used in the cardiorespiratory domain. Chest. 2001 Jan;119(1):256–270. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.1.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cantril H. The pattern of human concerns. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Antonovsky A. Health, stress, and coping. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eriksson M, Lindström B. Validity of Antonovsky's sense of coherence scale: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005 Jun;59(6):460–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.018085. http://jech.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15911640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kendzierski D, DeCarlo KJ. Physical activity enjoyment scale: Two validation studies. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1991;13(1):50–64. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mullen SP, Olson EA, Phillips SM, Szabo AN, Wójcicki TR, Mailey EL, Gothe NP, Fanning JT, Kramer AF, McAuley E. Measuring enjoyment of physical activity in older adults: invariance of the physical activity enjoyment scale (paces) across groups and time. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:103. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-103. http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/8//103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koelen MA, van den Ban AW. Health education and health promotion. Wageningen: Wageningen academic publishers; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation. London: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koelen MA, Vaandrager L, Wagemakers A. What is needed for coordinated action for health? Fam Pract. 2008 Dec;25(Suppl 1):i25–31. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn073. http://fampra.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18936114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wagemakers A, Koelen MA, Lezwijn J, Vaandrager L. Coordinated action checklist: a tool for partnerships to facilitate and evaluate community health promotion. Glob Health Promot. 2010 Sep;17(3):17–28. doi: 10.1177/1757975910375166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glasgow RE, McKay HG, Piette JD, Reynolds KD. The RE-AIM framework for evaluating interventions: what can it tell us about approaches to chronic illness management? Patient Educ Couns. 2001 Aug;44(2):119–127. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.EuroQoL EuroQoL. 2012. [2012-11-08]. EQ-5D-3L http://www.euroqol.org/eq-5d-products/eq-5d-3l.html.

- 53.Bowling A. Measuring health: a review of quality of life measurement scales. Maidenhead, England: Open University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morris S, Devlin N, Parkin D. Economic analysis in health care. Chichester: J. Wiley & Sons; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coffey A, Atkinson P. Making sense of qualitative data: complementary research strategies. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Silverman D. Interpreting qualitative data: methods for analyzing talk, text and interaction. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992 Jul;112(1):155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ooms L, Veenhof C. Nivel. Utrecht: NIVEL Netherlands institute for health services research; 2011. [2013-01-09]. Evaluatie van de implementatiefase van het Nationaal Actieplan Sport en Bewegen, setting sport: resultaten proces- en effectevaluatie. [Evaluation of the implementation phase of the National Action Plan for Sport and Exercise, sport setting: results process and impact evaluation] http://nvl002.nivel.nl/adlibweb/dispatcher.aspx?action=search&database=ChoicePublicat&search=priref=1002117. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leemrijse CJ, Ooms L, Veenhof C. NIVEL. Utrecht: NIVEL Netherlands institute for health services research; 2011. [2013-01-09]. Evaluatie van kansrijke programma's om lichaamsbeweging in de bevolking te bevorderen http://nvl002.nivel.nl/adlibweb/detail.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vaandrager L, Wagemakers A, Saan H. Evidence in gezondheidsbevordering [Evidence in health promotion] Tijdschr Gezondheidswetensch. 2010;88(5):270–276. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cohen DJ, Crabtree BF. Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: controversies and recommendations. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):331–9. doi: 10.1370/afm.818. http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18626033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]