Abstract

It is unknown whether pathological reports of ischemia obtained from gastroduodenal biopsy suggests a diagnosis, prognosis or requires additional evaluation. The aim of this study was to review the natural history, clinical presentation, endoscopic appearance, treatments and major clinical outcomes of patients with gastroduodenal ischemia. Case series of fourteen patients with variable etiologies, seven patients with gastric and seven patients with duodenal origin were obtained from a search of our endoscopic pathologic database for reports of histological ischemia. The most common indication for upper endoscopy was upper gastrointestinal bleeding (71%). Half of the endoscopic lesions appeared very severe. There were six cases of rebleeding (43%) and four deaths (29%). CT scanning was frequently used (12 cases, 86%), but was diagnostic in only three cases. Patients with underlying vascular pathology have substantial 6-month mortality (29%).

Introduction

Although non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and H. pylori are the major causes of gastroduodenal (GD) ulcer, GD ischemia is not uncommonly encountered in clinical practice account for GD injury/ulcer especially in particular settings. Signs and symptoms include gastrointestinal bleeding, abdominal pain, abdominal tenderness and perforation. GD ischemia is usually associated with vascular processes. The most frequent vascular causes include the chronic splanchnic syndrome characterized by multi-vessel celiac and mesenteric stenosis or occlusion (1–3) and iatrogenic cessation of blood supply (i.e. non target chemoembolization or surgical ligation (4, 5). Additional vascular causes that have been clinically linked to GD ischemia include mesenteric vein thrombosis (6, 7) and portal hypertension (8). These entities alter blood flow and microcirculatory physiology leading to hypoxia and reperfusion injury that can cause histological changes of ischemic injury. Cardinal pathohistologic features of ischemia include vascular congestion, edema and coagulative mucosal necrosis. With reperfusion and possible superinfection, both acute and chronic inflammation become visible and exudate or pseudomembrane may be evident endoscopically.

However, non-vascular causes have also been associated with histological ischemia. Stress related mucosal disease (SRMD) in patients experiencing burns (9), shock or sepsis (10), and low blood flow state have been shown to induce the above noted histological features of ischemia. Shunting of the splanchnic blood supply in these patients leads to impaired mucosal protection and subsequently development of mucosal ischemia (11, 12).

Literature review found case reports for less common associated conditions with GD ischemia. GD ischemia has been reported sparsely in acute aortic dissection (13), aortic coarctation (in newborn) (14), acute pancreatitis with pancreatic pseudocyst, hernia (hiatal, paraesophageal and diaphragmatic hernia) (15), small bowel obstruction (16), massive gastric dilatation (17), post endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer (18), post laparoscopic fundoplication (19), postoperative conditions (distal pancreatectomy with celiac axis resection, subtotal gastrectomy, highly selective vagotomy, splenectomy, gastric restrictive procedure using staplers, esophageal surgery) (20, 21) and cocaine abuse (22).

Biopsy is not routinely performed during endoscopy for typical GD ischemic cases unless the endoscopic findings are atypical or extensive or suspicion of other diseases such as malignancy. Furthermore, histological observation of ischemia does not frequently suggest an underlying cause in the absence of histological clues such as intravascular fibrin, vasculitis or amyloid. Therefore, the clinical relevance and prognostic value of a GD biopsy with histological ischemic is unknown. This lack of the information leads to uncertainty of whether pathological reports of ischemia obtained from GD biopsy suggest a diagnosis, prognosis or requires additional evaluation.

This report is the first case series on GD ischemia. We reviewed clinical data on 14 patients identified at our institution whose pathological reports confirmed ischemia. Our aim was to better characterize the clinical features of this entity, survey the range of underlying diseases leading to ischemia, study endoscopic features and evaluate prognostic endpoints including rebleeding and death.

Case series

After Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, a search of the UCLA Department of Pathology report database was performed using the words “ischemia” or “ischemic” during 1993 to 1997 and 2002 to 2007. Demographic information including age, sex and hospitalization status and etiology of the lesions was collected from medical records. Endoscopic images and pathology reports were reviewed. The types of treatment, rebleeding and mortality, including cause of death, were recorded. If obtained, results of abdominal computerized tomography (CT) scan were recorded. The etiologies, endoscopic features, anatomic locations and major outcomes are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Etiologies, endoscopic features, locations, and outcomes in 14 patients found to have ischemic features on biopsy.

| Patient | Etiology of ischemia | Extensive endoscopic features | Location | Surgery | Rebleeding | Death (days after diagnosis) | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stress ulcer | - | Proximal stomach | - | Yes | - | |

| 2 | Stress ulcer | Large ulceration | Proximal stomach | - | - | - | |

| 3 | TACE | - | Second duodenum | - | - | 98 | Unknown |

| 4 | TACE | - | Proximal stomach | - | - | 28 | Multi-organ failure |

| 5 | Unknown | Large, luminal narrowing | Second duodenum | - | - | - | |

| 6 | Unknown | Black mucosa with exudate | Gastric body | - | Yes | - | |

| 7 | Hypotension | Circumferential | Second duodenum | - | - | - | |

| 8 | Stress ulcer | - | Gastric body | - | - | - | |

| 9 | Mesenteric ischemia | Pale mucosa | Second duodenum | - | Yes | - | |

| 10 | Hypotension | Large, with exudate | Duodenal bulb | - | Yes | 5 | UGI bleeding |

| 11 | H. pylori ulcer | - | Gastric body | - | - | - | |

| 12 | Portal hypertension | - | Proximal stomach | - | - | - | |

| 13 | Amyloidotic vasculitis | Pseudomembranes | Second duodenum | Bowel resection | Yes | 63 | Necrotic bowel |

| 14 | Atheroscleroticdisease | - | Second duodenum | SMA thrombectomy and bowel resection | Yes | - |

SMA, superior mesenteric artery; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; UGI, upper gastrointestinal.

Patient Demographics

Fourteen patients were identified with GD ischemia over a nine year period. Seven males and seven females with a mean age of 57 years (range: 39 to 84 years) were included. All but one patient was an inpatient (93%) and six (43%) of these inpatients were in an intensive care unit. The most common indication for endoscopy was upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding in 10 (71%) patients, while the remaining four patients underwent endoscopy for other indications including suspected obstruction or stricture, abdominal pain, history of duodenal ulcer or recurrent vomiting.

Endoscopic Appearance

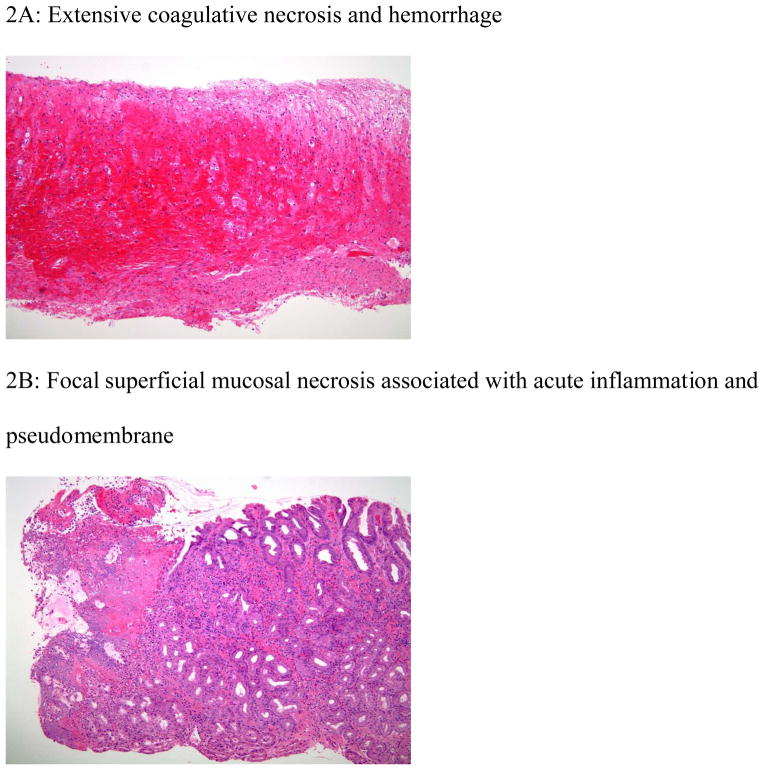

Endoscopic lesions (Figure 1A–B) are shown. Seven patients had gastric lesions and seven patients had duodenal lesions. Endoscopic features were large or circumferential lesions, exudative, pseudomembranous, black or pale mucosa. Half of the endoscopic lesions appeared extensive (Table 1). A single case of duodenal ulceration with duodenitis was found to be oozing blood at time of endoscopy. No other ulcers had stigmata of recent hemorrhage.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic features of upper gastrointestinal ischemia

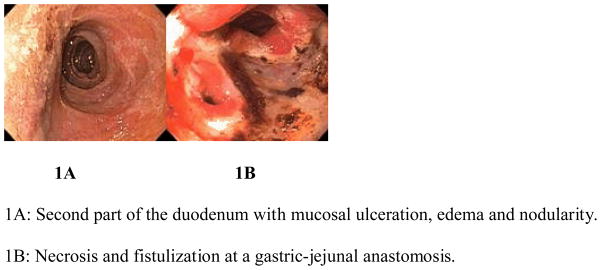

Histological features of ischemia

The histology findings from this series were congestion, hemorrhage, inflammation, coagulative necrosis, surface epithelium denudation, ulceration and pseudomembrane (Figure 2A–B).

Figure 2.

Histologic features of ischemic injury

Use of CT Scanning

CT scanning was frequently used (12 cases, 86%) and was only helpful in diagnosis in three of those cases. Findings included diffuse vascular calcifications, splenic vein thrombosis underlying portal gastropathy and tumor invasion of the superior mesenteric artery and superior mesenteric vein.

Treatment and Outcome

Twelve patients (86%) were treated with medical therapy alone (intravenous proton pump inhibitor). Two patients were managed surgically. A vasculopathic patient with a superior mesenteric artery clot did well with thrombectomy and bowel resection. Six patients (43%) developed clinically significant UGI rebleeding (requiring repeat endoscopy). There were four (29%) deaths which were related to post-transarterial chemoembolization in two patients (gastric and duodenal lesion), amyloidosis (gangrenous duodenal lesion) in one patient and persistent hypotension in one patient (duodenal lesion).

Discussion

This is a case series of 14 patients with histological observed ischemia on endoscopic GD biopsy. Given the abundance of inpatients in our group with significant mortality (29% within 6 months), histological ischemia appears to occur more frequently in patients with severe illness. Although this case series reported cases with biopsy proven ischemia, this high mortality can be related to selection bias by having biopsy in only severe cases. Endoscopists usually make GD ischemia diagnosis according to endoscopic findings supportive by the predisposing underlying conditions without obtaining biopsies unless the endoscopic findings are atypical or extensive or suspected other diseases such as malignancy. Therefore the selected patients very likely do not represent the spectrum of patients with ischemic changes. The patient selection is based on biopsies. A larger proportion of patients may have had GD ischemia when biopsies were not obtained. A wide variety of etiologies predisposing to GD ischemia including vascular and non-vascular cause were observed. This diagnostic diversity functions as a clinical corollary to previous basic science observations that ischemia is a wide-ranging mechanism of tissue injury not limited to gross vascular compromise. Our series suggests that vascular pathology was the predominate etiology and associated with worse outcome (3 out of 4 death cases are vascular etiology). CT can help detect features suggestive of bowel ischemia such as wall thickening or thumbprinting, mucosal enhancement, intramural air, dilation and portal venous gas (23). Also, CT scan helps in determining the etiology of ischemia in some cases, as in this case series where 21% of CT’s were positive. Findings such as thrombosis, extensive vascular calcifications or tumor progression may guide specific therapeutic modalities in certain clinical scenarios.

GD ischemic lesions have classically been described as irregularly shaped ulcers with sloping edges and white sclerotic bases often with small surrounding erosions (24–27). We reported that half of the cases with ischemic histology did possess atypical or aggressive endoscopic findings such as large ulceration, pseudomembrane or necrosis. Again, the preponderance of extensive endoscopic findings may be attributable to sampling bias as these lesions were biopsied with atypical or extensive lesions or with the intent of ruling out cancer. Also, these 14 cases may represent only patients who have atypical ischemic presentation or extensive endoscopic lesions that required pathological diagnosis.

In our series, endoscopic therapy was not used, since no lesions had major stigmata of recent hemorrhage (SRH). Our previously reported data on bleeding colonic ischemia showed that focal ulcers are uncommon (5 out of 65 cases-7.7%) but if it presents with SRH, the endoscopic treatment has a role and is effective. Our previous data support the usefulness of epinephrine injection and hemoclips placement for focal ulcer with SRH. However, if SRH were found in GD lesions with UGI bleeding, we would recommend avoiding cautery when necrosis is suspected, especially for the thin duodenal mucosal wall, and utilization of hemoclips, which is safer. Surgical management is warranted in specific clinical settings.

Ischemia should be suspected in individuals with underlying vascular, predisposing condition for vascular compromise, non-NSAIDs, non-H. Pylori ulcer, atypical lesion, ulcer refractoriness to standard peptic ulcer therapy and severe recurrent hemorrhage. Given it is relative rarity, potential for poor outcome, option of endoscopic management and revasculization (3, 28, 29), close follow up and use of an imaging study may be warranted. Individualized management with consideration of extent of ischemia and clinical setting is necessary for appropriate triage.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Jensen’s contribution was partially supported by NIH-NIDDK Human Studies Core of NIH-NIDDK AM41301 CURE Digestive Diseases Research Center and an NIH K24 grant (02650).

References

- 1.Somin M, Korotinski S, Attali M, Franz A, Weinmann EE, Malnick SD. Three cases of chronic mesenteric ischemia presenting as abdominal pain and Helicobacter pylori-negative gastric ulcer. Dig Dis Sci. 2004 Nov-Dec;49(11–12):1990–5. doi: 10.1007/s10620-004-9607-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaptik S, Jamal Y, Jackson BK, Tombazzi C. Ischemic gastropathy: an unusual cause of abdominal pain and gastric ulcers. Am J Med Sci. Jan;339(1):95–7. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181bb41b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mercogliano G, Tully O, Schmidt D. Gastric ischemia treated with superior mesenteric artery revascularization. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Apr;5(4):A26. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morante A, Romano M, Cuomo A, de Sio I, Cozzolino A, Mucherino C, et al. Massive gastric ulceration after transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006 Apr;63(4):718–20. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotani T, Fujimura T, Amagase K, Okabe S, Takeuchi K. A novel gastric lesion model induced in rats by partial gastric vascular ligation. Inflammopharmacology. 2005;13(1–3):261–72. doi: 10.1163/156856005774423926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Llovera I, Roit Z, Kiriaki S, Sama A, Loscalzo J, Goyal N. Mesenteric ischemia and proteins deficiency: A rare case report. J Emerg Med. 2008 Jan 2; doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cappell MS, Mikhail N, Gujral N. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage and intestinal ischemia associated with anticardiolipin antibodies. Dig Dis Sci. 1994 Jun;39(6):1359–64. doi: 10.1007/BF02093805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwao T, Toyonaga A, Ikegami M, Oho K, Sumino M, Harada H, et al. Reduced gastric mucosal blood flow in patients with portal-hypertensive gastropathy. Hepatology. 1993 Jul;18(1):36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czaja AJ, McAlhany JC, Pruitt BA., Jr Acute gastroduodenal disease after thermal injury. An endoscopic evaluation of incidence and natural history. N Engl J Med. 1974 Oct 31;291(18):925–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197410312911801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas M. Gastric infarction associated with septic shock and high-dose vasopressor use. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2003 Aug;31(4):470–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolkman JJ, Mensink PB. Non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia: a common disorder in gastroenterology and intensive care. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003 Jun;17(3):457–73. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6918(03)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duerksen DR. Stress-related mucosal disease in critically ill patients. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003 Jun;17(3):327–44. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6918(03)00028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jutaghokiat S, Angsuwatcharakon P, Imraporn B, Ongcharit P, Udomsawaengsup S, Rerknimitr R. Acute aortic dissection causing gastroduodenal and hepatic infarction. Endoscopy. 2009;41( Suppl 2):E88–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turowski C, Downes MR, Devaney DM, Donoghue V, Gillick J. A novel association of gastric ischaemia and aortic coarctation. Pediatr Surg Int. Aug;26(8):843–6. doi: 10.1007/s00383-010-2631-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shafii AE, Agle SC, Zervos EE. Perforated gastric corpus in a strangulated paraesophageal hernia: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2009;3:6507. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-3-6507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steen S, Lamont J, Petrey L. Acute gastric dilation and ischemia secondary to small bowel obstruction. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2008 Jan;21(1):15–7. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2008.11928348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baldassarre E, Capuano G, Valenti G, Maggi P, Conforti A, Porta IP. A case of massive gastric necrosis in a young girl with Rett Syndrome. Brain Dev. 2006 Jan;28(1):49–51. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Probst A, Maerkl B, Bittinger M, Messmann H. Gastric ischemia following endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. Mar;13(1):58–61. doi: 10.1007/s10120-009-0539-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huguet KL, Hinder RA, Berland T. Late gastric perforations after laparoscopic fundoplication. Surg Endosc. 2007 Nov;21(11):1975–7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schein M, Saadia R. Postoperative gastric ischaemia. Br J Surg. 1989 Aug;76(8):844–8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800760828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kondo S, Katoh H, Hirano S, Ambo Y, Tanaka E, Maeyama Y, et al. Ischemic gastropathy after distal pancreatectomy with celiac axis resection. Surg Today. 2004;34(4):337–40. doi: 10.1007/s00595-003-2707-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hon DC, Salloum LJ, Hardy HW, 3rd, Barone JE. Crack-induced enteric ischemia. N J Med. 1990 Dec;87(12):1001–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herbert GS, Steele SR. Acute and chronic mesenteric ischemia. Surg Clin North Am. 2007 Oct;87(5):1115–34. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Force T, MacDonald D, Eade OE, Doane C, Krawitt EL. Ischemic gastritis and duodenitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1980 Apr;25(4):307–10. doi: 10.1007/BF01308523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cherry RD, Jabbari M, Goresky CA, Herba M, Reich D, Blundell PE. Chronic mesenteric vascular insufficiency with gastric ulceration. Gastroenterology. 1986 Dec;91(6):1548–52. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)90214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hojgaard L, Krag E. Chronic ischemic gastritis reversed after revascularization operation. Gastroenterology. 1987 Jan;92(1):226–8. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90864-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allende HD, Ona FV. Celiac artery and superior mesenteric artery insufficiency. Unusual cause of erosive gastroduodenitis. Gastroenterology. 1982 Apr;82(4):763–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Becker S, Bonderup OK, Fonslet TO. Ischaemic gastric ulceration with endoscopic healing after revascularization. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Apr;18(4):451–4. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200604000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liberski SM, Koch KL, Atnip RG, Stern RM. Ischemic gastroparesis: resolution after revascularization. Gastroenterology. 1990 Jul;99(1):252–7. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]