Abstract

Surges of nitric oxide compromise mitochondrial respiration primarily by competitive inhibition of oxygen binding to cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV) and are particularly injurious in neurons, which rely on oxidative phosphorylation for all their energy needs. Here, we show that transgenic overexpression of the neuronal globin protein, neuroglobin, helps diminish protein nitration, preserve mitochondrial function and sustain ATP content of primary cortical neurons challenged by extended nitric oxide exposure. Specifically, in transgenic neurons, elevated neuroglobin curtailed nitric oxide-induced alterations in mitochondrial oxygen consumption rates, including baseline oxygen consumption, consumption coupled with ATP synthesis, proton leak and spare respiratory capacity. Concomitantly, activation of genes involved in sensing and responding to oxidative/nitrosative stress, including the early-immediate c-Fos gene and the phase II antioxidant enzyme, heme oxygenase-1, was diminished in neuroglobin-overexpressing compared to wild-type neurons. Taken together, these differences reflect a lesser insult produced by similar concentrations of nitric oxide in neuroglobin-overexpressing compared to wild-type neurons, suggesting that abundant neuroglobin buffers nitric oxide and raises the threshold of nitric oxide-mediated injury in neurons.

Keywords: neuroglobin transgene, nitric oxide, primary neurons, mitochondrial respiration, ATP synthesis, bioenergetics

1. INTRODUCTION

Neuroglobin is a recently discovered globin protein, which is expressed primarily in neuronal cells [1]. Despite its early evolutionary origins and strong sequence and structure conservation [2], its precise function is not well understood [3]. Neuroglobin (Ngb) has been implicated in several paradigms of neuroprotection, involving improved oxygen homeostasis, oxygen sensing, neutralization of free radicals, redox cycling [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9], as well as neuron type-specific regulatory functions [10, 11]. We recently generated a transgenic mouse (Ngb-tg) with physiologically relevant neuron-specific Ngb overexpression under the control of synapsin-1 promoter and investigated neuroprotection by Ngb in the paradigm of combustion smoke-inhalation injury to the brain [12]. We found that following smoke inhalation, DNA integrity and mitochondrial function were better preserved in Ngb-tg when compared to the wild-type mouse brain. Because nitration of mitochondrial proteins is among toxic outcomes of smoke inhalation [13] and Ngb can bind nitric oxide [14, 15], we asked whether neuroglobin could sequester excess of nitric oxide (NO) and thereby reduce cytotoxicity in Ngb-tg neurons. To test this possibility, we compared effects of elevated NO on a range of mitochondrial respiratory activities, in primary neuronal cultures derived from either wild-type or Ngb-tg mice.

While arguably cellular NO has many vital physiological roles, its overproduction under pathophysiological conditions has been implicated in diverse disease states, including initiation of neurodegenerative processes, particularly via impairment of neuronal energy metabolism [16, 17, 18, 19]. One well-characterized mechanism of NO-mediated cytotoxicity, is compromise of mitochondrial function via competitive inhibition of oxygen binding at the active center of cytochrome c oxidase [20]. Because neurons rely primarily on oxidative phosphorylation for all bioenergetic needs, interference with mitochondrial activities is deleterious in neurons [21, 22, 23, 24]. Here, we investigated effects of sustained exogenous supplementation of NO on mitochondrial respiration and observed lesser impairments of central mitochondrial parameters in primary cortical neurons derived from Ngb-tg when compared to wild-type mice. Interestingly, critical indicators of neuronal stress, including the early response gene c-Fos and the phase II antioxidant response enzyme heme oxygenase-1, were stimulated to a lesser degree, indicative of higher threshold for NO-induced cellular stress and toxicity in Ngb-tg neurons.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Preparation and treatment of neuronal cultures

All mice handling procedures were approved by the University of Texas Medical Branch Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Ngb-tg mice overexpressing neuroglobin under the control of synapsin-1 promoter were generated as we previously described [12]. Experiments were performed with primary cortical neurons isolated from C57BL/6 wild-type and Ngb-transgenic mice embryos at gestation day 17 and cultured as described previously [25, 26, 27]. Briefly, cortices were dissected, disrupted mechanically in calcium-magnesium free Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS) and digested with 1 mg/ml Papain (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ) in Hibernate A Medium (Brain Bits LLC, Springfield, IL, USA) at 30°C for 9 min. DNase I (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) was added at 3 μM, incubated at 25°C, gently triturated, passed through 70 μm strainer and pelleted at 250 g for 8 min. Pellet was resuspended in DPBS with 30 μg/ml DNase I, centrifuged and resuspended in neurobasal medium (NBM) supplemented with 2% (v/v) B-27, 0.5 mM L-glutamine (Glutamax®) and seeded at 1.5×105/cm2 in poly-D-Lysine-coated plates. Medium was changed after 30 min and cultures maintained at humidified atmosphere of 95% air/5% CO2. This procedure yielded >95% neurons. On seventh day in culture (DIV7), neurons were incubated in presence of 100 μM of slow release (half-life 20 h) NO donor DetaNonoate (3,3-Bis-aminoethyl-1-hydroxy-2-oxo-1-triazene, CAS: 146724-94-9, cat #A5581, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 12 h and processed for the various assays in parallel with untreated control cultures. Following supplementation of DetaNonoate, nitric oxide levels were assessed indirectly by measuring nitrite in NBM alone or in the presence of neuronal cultures. Nitrite concentrations were determined using the Griess Reagent System (Promega, cat#PR-G2930). Concentrations were as follows: 1.3±0.01 μM nitrite in NBM and 105±1.5 μM nitrite 12 h after addition of 100 μM DetaNonoate. Non-treated neuronal culture medium contained 2.03±0.03 μM nitrite, whereas at six and 12 h after DetaNonoate supplementation to neuronal culture, nitrite concentration was 114±2.3 μM and 82±5.5 μM, respectively.

2.2 Real-time PCR determination mRNA levels and of mtDNA copy number

Total RNA was isolated from cultured neurons using RNeasy plus mini kit (Qiagen). RNA was reverse transcribed using iScript RT supermix (Biorad) which includes both random and oligo dT primers. Real-time PCR analyses were done using CFX96 Real-Time System (Biorad). 18s gene was used as reference gene. PCR reactions were assembled with SSO FAST Evagreen supermix (Biorad) and done in duplicates. PCR program was: 95°C 2 min, 40 cycles of 95°C 5 sec, 55°C 15 sec with plate reading and subsequent melting curve analysis. Data represent the average from at least 3 independent experiments. The relative amount of target gene was calculated as described [28] using the formula: −ΔΔCt=[(CT gene of interest − CT internal control) sample − (CT gene of interest − CT internal control) control]. Mitochondrial DNA copy number was quantified by same method using total DNA isolated from wild type and Ngb-tg DIV7 controls and neurons after NO exposure. The single-copy nuclear beta-2-microglobulin (B2M) gene and mitochondria encoded cytochrome oxidase subunit III (Cox III) gene were amplified. Primers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers list

| Symbol | Accession # | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18s | NR_003278 | 5′-gtaacccgttgaaccccatt-3′ | 5′-ccatccaatcggtagtagcg-3′ |

| c-Fos | NM_010234 | 5′-gggacagcctttcctactacc-3′ | 5′-gatctgcgcaaaagtcctgt-3′ |

| HO-1 | NM_010442 | 5′-gtcaagcacagggtgacaga-3′ | 5′-atcacctgcagctcctcaaa-3′ |

| B2M | NM_009735 | 5′-atccaaatgctgaagaacgg-3′ | 5′-atcagtctcagtgggggtga-3′ |

| Cox III | JF286601.1 | 5′-caattacatgagctcatcatagc-3′ | 5′-ccatggaatccagtagcca-3′ |

2.3 Immunocytochemistry

On DIV7 primary neuronal cultures growing on coverslips were gently washed twice with Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) for 30 min at 37°C. Cover slips were rinsed twice with PBS, and permeablized with 0.1% Triton X-100 mixed with 0.1% sodium citrate (in PBS) for 9 min. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked for 40 min at 37°C with 3% BSA (w/v) and 1% Donkey serum (v/v) in PBS. The following primary antibodies were used: chicken anti-neuroglobin (Biovendor-RD181043050); rabbit anti-Map2 (Chemicon-AB 5622); mouse anti-Map2 (Millipore-05346); mouse anti-nitrotyrosine (Upstate-05233); goat anti-Tfam (Santa Cruz sc-23588); rabbit anti-c-Fos (Calbiochem-PC38). Following three washes with 1% BSA in PBS coverslips were incubated 45 min/37°C in the dark with combinations of the following Alexa-dye conjugated secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor® 488 conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG, Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated donkey anti-mouse, Alexa Fluor® 594 conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG, and Alexa Fluor® 594 conjugated donkey anti-Chicken IgG. Following three washes with PBS coverslips were mounted with Prolong® Gold Antifade/Dapi (Invitrogen) and examined using IX71 Olympus fluorescence microscope equipped with QIC-F-M-12-C cooled digital camera (QImaging, Surrey, BC, Canada) with the software QCapture Pro 5.

2.4 Measurement of intracellular ATP

Cellular ATP content was determined using ATP Bioluminescence Assay Kit HS II (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) with some modifications [27]. Briefly, cultures were collected in 150 μl of cell lysis reagent, mixed with equal amount of dilution buffer, centrifuged at 16,000 g/8 min at 4°C, supernatants transferred to black microtiter plates and mixed with equal amount of luciferase reagent. Luminescence was measured using TECAN Genios plate Reader. ATP amounts were calculated from ATP standard graph using Magellan™ software. ATP was normalized to total protein amount and presented as percent of control. ATP average values for controls were consistent with the reported range [29].

2.5 Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay

LDH release from damaged neurons was assessed calorimetrically with the Cytotoxicity Detection LDH Kit (cat # 11644793001 Roche, Indianapolis, USA) according to manufacturer instructions. Activity is proportional to colorimetric reduction of tetrazolium salt measured at 490 nm (GeniosTecan-microplate reader equipped with Magellan™ software). LDH released into medium from cultures acutely exposed to Triton X-100 was considered as 100% release and served to normalize LDH values obtained from experimental cultures.

2.6 Protein extracts and band-shift assays

Protein extracts and electromobility band-shift assays were done as we described [30] using a duplex oligomer carrying the consensus AP-1 binding motif 5′-CGCTTGATGAGTCAGCCGGAA-3′ (cat #E320A, Promega).

2.7 Measurements of oxygen consumption rates (OCR) in primary neuronal cultures

Mitochondrial respiratory profiles of cultured neurons were examined using the Seahorse XF24 extracellular flux analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience, North Billerica, MA), which measures oxygen consumption in intact cells as we described [27]: neurons were seeded at 3.3 × 105/cm2 in neurobasal medium on XF24 V7 plates coated with Poly-D-Lysine (Sigma); prior to measurements, medium was replaced with un-buffered Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Seahorse Bioscience) supplemented with 5 mM pyruvate, 25 mM glucose and 2 mM Glutamax (all media and reagents were adjusted to pH 7.4 at that time) and incubated in CO2 free incubator at 37°C for 1 h prior to XF24 measurements. Assay protocol was implemented by the XF24 Reader software Version 1.7 to sequentially measure oxygen consumption rates (OCR). Three measurements at 5-min intervals were recorded for each segment of the assay. To obtain respiration profiles for control and treated cultures, baseline OCR measurements were followed by sequential automated addition of reagents through the ports of XF24 cartridges to final concentrations of 1.2 μM oligomycin (O4876, Sigma), 0.6 μM carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP), (C2920, Sigma) and 2.7 μM antimycin A (A8674, Sigma), which were determined by titration in our experimental setting. Modulations of mitochondrial activities by these reagents are referred to as mitochondrial stress test and inform on mitochondrial status under given culture conditions [31, 32, 33]. The relative changes (%) in parameters of mitochondrial respiration were determined as follows: baseline mitochondrial oxygen consumption was defined as OCR after subtraction of non mitochondrial OCR (i.e., the portion retained after addition of antimycin A). Baseline OCR values obtained for non-treated cultures were considered as 100% while baseline OCR values for treated cultures were calculated as percent of each respective control. The portion of OCR devoted to ATP synthesis in controls (i.e., OCR which is eliminated after addition of oligomycin) was considered as 100%, while the portion eliminated by oligomycin in treated cultures was calculated as percent relative to respective control. The remaining OCR (i.e., baseline minus ATP synthesis-linked) feeds into proton leak. OCR portion feeding into proton leak in controls was set as 100% and as corresponding relative percent for treated cultures. Similarly, spare respiratory capacity (which equals maximal OCR minus baseline OCR) was set as 100% for control cultures and after treatment calculated as percent relative to control.

2.8 Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SEM obtained from 4–5 independent experiments, as indicated. One way ANOVA was employed to compare the means between treated and non-treated groups followed by post-hoc Tukey’s analysis to determine differences in means between two groups. P<0.05 was accepted as statistically significant. All calculations were performed with MegaStat® version 10.1 package for Excel.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Neuroglobin-overexpressing primary cortical neurons tolerate nitric oxide challenge to a greater extent than wild-type neurons

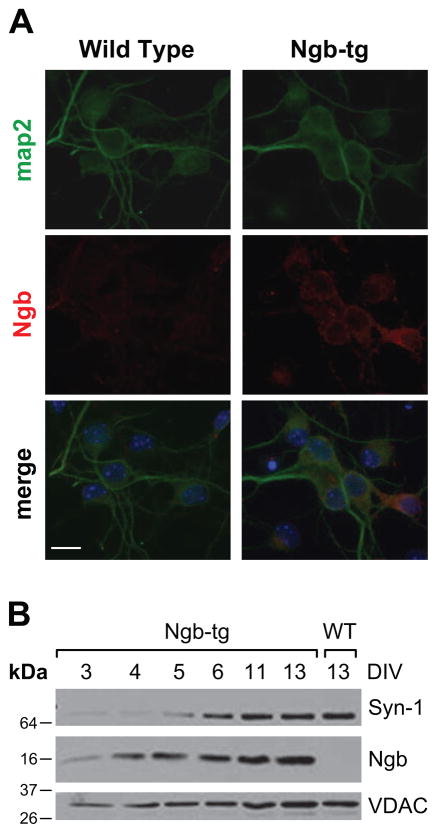

Primary neuronal cultures were derived from embryonic cortices of wild-type and Ngb-tg transgenic mice overexpressing neuroglobin under the control of synapsin-1 promoter [12]. Neuroglobin immunoreactivity was readily observed in neurons derived from Ngb-tg brains (red), while fluorescence was very weak in wild-type neurons (Fig 1A). Western blotting analyses revealed gradual time in culture-dependent (DIV3-13) increase in Ngb immunoreactivity in cortical Ngb-tg neurons (Fig 1B). As expected increases mirrored elevation of synapsin-1 levels with neuronal maturation and neurite development in culture; a similar pattern reflecting time-dependent mitochondrial biogenesis concomitant with neuronal maturation, was seen for the mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) protein.

Figure 1. Neuroglobin immunoreactivity in Ngb-tg and wild-type primary cortical neurons derived from E17 embryonic mouse brains.

(A) Representative immunofluorescent images of DIV7 cultured neurons reacted with anti map2 (neuronal marker, green) and anti-neuroglobin (red) antibodies are shown (nuclei stain blue with DAPI). Neuroglobin immunoreactivity is very weak or undetectable in wild-type neurons. In contrast, neuroglobin immunoreactivity is readily observed in Ngb-tg neurons (red, right panel), bar=10 μm. (B) Western blotting analysis of time in culture-dependent neuroglobin overexpression in Ngb-tg neurons. Expression of the synaptic protein, synapsin-1 (Syn-1) and the mitochondrial voltage dependent anion channel protein (VDAC) shown in parallel, reveals increases in protein levels with neuronal maturation in culture.

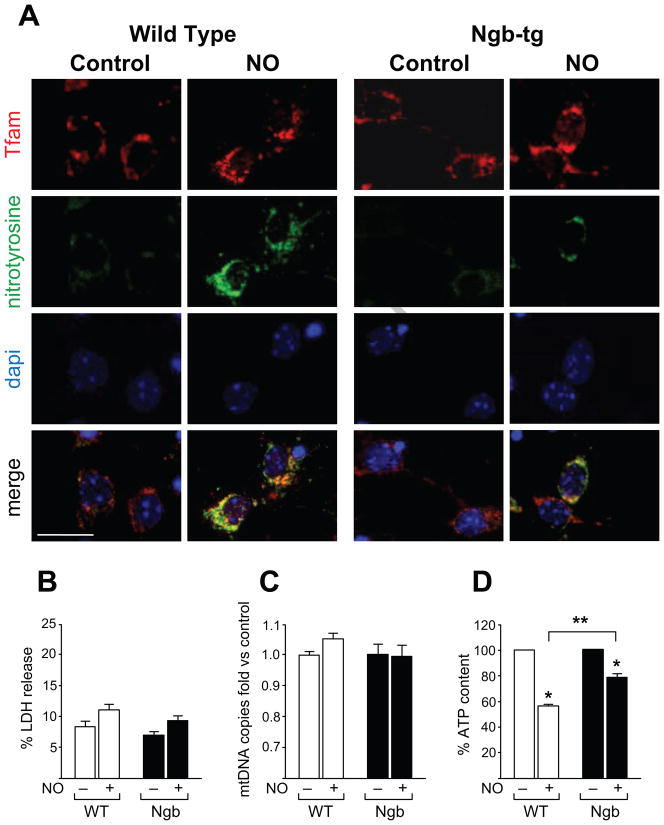

On DIV7, wild-type and Ngb-tg neuronal cultures were exposed to DetaNonoate a NO donor. This donor was selected because of controlled slow NO release (half-life ~20 h) and added to culture medium at concentration of 100 μM [34]. After 12-h incubation, protein nitration was assessed by immunoreactivity for the nitrotyrosine adduct (Fig 2A, green), while mitochondria were visualized by immunoreactivity of the mitochondrial transcription factor Tfam (red). Staining revealed that nitrotyrosine immunoreactivity increased to a lesser degree in Ngb when compared to wild-type neuronal cultures. No evidence for apoptotic changes in neuronal morphology, such as nuclear rounding or condensation was observed. Likewise, no significant increases in lactate dehydrogenase release reflecting membrane rupture were measured following nitric oxide exposure (Fig 2B). No differences in mtDNA copy number were detected by quantitative PCR analyses (Fig 2C) indicating that changes in mitochondrial mass play no role in neuron protection by neuroglobin under these conditions.

Figure 2. Nitric oxide exposure differentially affects protein nitration and ATP content of wild-type and Ngb-tg neurons.

(A) Immunofluorescent images of primary neuronal cultures reacted with anti mitochondrial transcription factor-Tfam (red) and anti nitrotyrosine-adduct (green) antibodies; nuclei stain blue with DAPI; bar=10 μm. On DIV7 cultures were incubated 12 h with 100 μM DetaNonoate (NO). In non-treated controls (left panel), nitrotyrosine immunoreactivity (green) was weak. Following treatment immunoreactivity intensified to a greater extent in wild-type than Ngb-tg neurons. (B) Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) release: measurement of LDH in medium did not revealed statistically significant changes induced by NO exposure in wild type or Ngb-tg cultures. Values were normalized to a complete release (100%) acutely induced by Triton X-100. (C) Mitochondrial DNA copy numbers for control and NO treated neurons determined by quantitative real time PCR, revealed no significant changes following NO exposure. (D) Cellular ATP content was measured in DIV7 neurons treated as above. ATP levels were determined using ATP Bioluminescence Assay and normalized to neuronal protein. ATP content was reduced by DetaNonoate (NO) exposure by more than 40% in wild-type and ~20% in Ngb-tg. All values are presented as means ± SEM for 4 independent experiments; *P<0.05 versus non-treated control; **P<0.05 treated Ngb-tg versus treated wild-type neurons.

Importantly, following NO exposures, measurements of cellular ATP content revealed a 42% decrease in the wild-type compared to only ~20% decrease in ATP content of Ngb-tg derived neurons (Fig 2D).

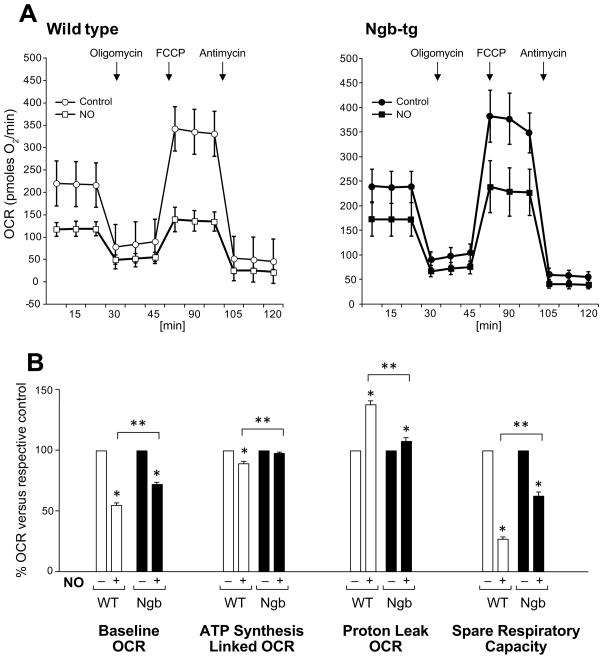

3.2 Elevated neuroglobin helps preserve mitochondrial respiratory activities during nitric oxide exposure

Because we observed better upholding of ATP content in neurons overexpressing Ngb, we asked whether specific respiratory/mitochondrial activities might be differentially affected, and contribute to these differences. Since neurons rely on oxidative phosphorylation for energy generation, we asked which parameters of mitochondrial respiration might be compromised by NO generated under these conditions. This was tested using the XF24 extracellular flux analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience), which records in real time oxygen consumption rates (OCR) in living cells [35]. We compared effects of elevated NO on respiration profiles of wild-type and Ngb overexpressing neurons. The investigated parameters constitute the mitochondrial stress test and include baseline OCR, OCR linked to ATP synthesis, OCR feeding into proton leak, maximal respiration, spare respiratory capacity and non-mitochondrial oxygen consumption (Fig 3). Neuronal baseline oxygen consumption and consecutive changes evoked by mitochondrial effectors (stress test), which in combination generate a cell type-specific respiratory profile, were compared in wild-type and Ngb-tg primary neuronal cultures. The average baseline OCR for DIV7 wild-type neurons seeded at 105/well reached ~220 pmoles O2/min (circles), including non-mitochondrial oxygen consumption which was determined after addition of antimycin A, the potent inhibitor of mitochondrial respiration. The relative portion of non-mitochondrial oxygen consumption was about 23% of baseline and remained stable (Fig 3), suggesting that under these conditions NO does not affect oxygen consuming processes, which are non-mitochondrial. The portion of mitochondrial oxygen consumption devoted to ATP synthesis (which is blocked by oligomycin) was ~80%, while the remaining ~20% fed into proton leak. Maximal respiratory rate was determined after addition of FCCP, an ionophore which transfers protons across the membrane independently of ATP synthesis and reveals the full potential for oxygen consumption. The difference between maximal and baseline OCR is defined as spare respiratory capacity (SRC), which varies in cell type-specific manner and serves a measure of mitochondrial resilience. In the case of DIV7 neurons, OCR feeding the spare respiratory capacity was nearly 70% above baseline. No significant differences in respiration profiles were noted between unchallenged wild-type and Ngb neurons. However, marked differences (Fig 3) emerged after wild-type (Fig 3A, empty squares) and Ngb neurons (solid squares) were challenged by 12-h exposures to 100 μM DetaNonoate. Baseline OCR was reduced by nearly 50% in wild-type versus 30% in Ngb-neurons (Fig 3B). Relative oxygen consumption associated with ATP synthesis was reduced by ~20% in wild-type with no significant reduction in Ngb neurons. Importantly, while oxygen consumption feeding the proton leak increased by nearly 40% in wild-type (Fig 3B), only a 10% increase in proton leak was observed in Ngb neurons consistent with better preservation of mitochondrial integrity and function. Likewise, respiratory reserve capacity measured after addition of FCCP was reduced by ~70% in wild-type versus only 40% in Ngb (Fig 3B). In combination, these measurements show that following NO challenge, mitochondrial stress test results were significantly better in Ngb-tg compared to wild-type neurons.

Figure 3. Differential effects of nitric oxide on mitochondrial respiratory profiles in wild-type and Ngb-tg neurons.

On DIV7 neurons were incubated with 100 μM DetaNonoate (NO) for 12 h and along with non-treated control cultures, processed for measurement of oxygen consumption rates (OCR) with the XF24 metabolic analyzer (A). Respiratory profiles (stress test) obtained for non-treated control neurons (circles) show baseline OCR of approximately 200 pmoles O2/min/105 neurons. Sequential, in port additions of effectors of mitochondrial activities (downward arrows), reveal that under normal conditions nearly 80% of oxygen consumption feed mitochondrial respiration: of this OCR ~80% support ATP synthesis, with nearly 20% lost to proton leak. Spare respiratory capacity (SRC) defined as FCCP-induced increase in OCR over baseline respiration is at ~70% for untreated cultures. Following 12-h incubation with 100 μM DetaNonoate mitochondrial profiles are differentially modulated: wild-type baseline OCR (empty rectangles) dropped by 50% versus 30% for Ngb-tg (solid rectangles). Proton leak increased by 40% in wild-type versus less than 10% in Ngb-tg. A 70% reduction in SRC was measured for wild-type compared to only 40% reduction in Ngb-tg neurons. (B) Changes induced by treatment versus respective controls: quantifications for the different segments of respiratory profiles (baseline, ATP synthesis, proton leak and spare respiratory capacity) are presented as means ± SEM for 4–5 independent experiments (wild-type-empty bars; Ngb-solid bars): * P<0.05 versus respective control; **P<0.05 change for Ngb versus change for wild-type neurons.

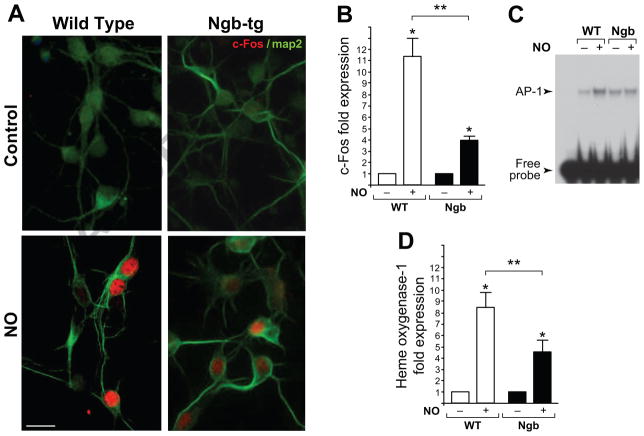

3.3 Neuronal stress indicator genes c-Fos and Heme oxygenase-1 are induced by nitric oxide to a lesser extent in Ngb-tg than in wild-type neurons

Because c-Fos is a sensitive biomarker of neuronal activation and neuronal stress responses in vivo and in vitro, we asked whether the extent of c-Fos induction might inform on subtle differences between cellular stress levels in wild-type and Ngb neurons challenged by limited sustained exposure to NO (Fig 4). Following NO exposures, immunofluorescent staining analyses revealed markedly stronger c-Fos nuclear immunoreactivity (red) in wild-type when compared to Ngb neurons (Fig 4A). Real-Time qPCR analyses revealed a 12-fold induction of c-Fos mRNA in wild-type, versus only a 4-fold induction in Ngb neurons (Fig 4B). Attenuated transcriptional upregulation was mirrored at the protein level in band-shift assays for activating protein-1 (AP-1) response element, which is the binding target for the c-Fos/c-Jun heterodimer transcription factor. Band-shift analyses revealed greater augmentation of AP-1 binding in response to NO in the wild-type when compared to Ngb neurons (Fig 4C). AP-1 binding elements are present in proximal promoter regions of phase ll, stress response genes, contributing to their transcriptional up regulation under cytotoxic conditions. Here, real time-qPCR assays revealed a greater, about 8-fold transcriptional induction of mRNA for the critical phase II enzyme, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) in wild-type neurons when compared to more modest ~4-fold induction in Ngb-tg neurons exposed to NO, suggestive of a lesser disruption of cellular homeostasis.

Figure 4. Differential nitric oxide-induced upregulation of c-Fos and Heme oxygenase-1 genes in wild-type and Ngb-tg neurons.

(A) Immunofluorescent images of DIV7 neurons reacted with anti map2 antibody (green) and anti-c-Fos (red). Nuclear c-Fos immunoreactivity is strongly induced by 100 μM DetaNonoate (NO) in wild-type (left) and to a lesser extent in Ngb-tg (right) neurons (scale bar=10 μm). (B) NO-induced c-Fos mRNA expression. Relative induction measured by RT-qPCR is presented as bar graphs (means ± SEM of 5 independent experiments; *P<0.01 treated Ngb versus treated wild-type neurons). (C) AP-1 bandshift assay for DetaNonoate exposed and untreated wild-type and Ngb-tg neurons. Free probe and AP-1 band-shift are indicated. (D) NO induced Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) mRNA expression. Relative induction measured by RT-qPCR presented as bar graphs showing fold induction relative to control levels (means ± SEM of 5 independent experiments; *P<0.01 for treated Ngb versus treated wild-type neurons).

4. DISCUSSION

We found that cultured primary neurons derived from neuroglobin overexpressing transgenic mice are less susceptible to nitric oxide cytotoxicity than wild-type neurons. We show that overexpressed neuroglobin attenuates NO-induced impairments of mitochondrial respiratory activities and helps sustain neuronal ATP content. Subsequently, the c-Fos gene, a sensor of neuronal stress, is activated to a lesser degree, consistent with attenuated response to NO exposure. Diminished stimulation of c-Fos in Ngb-tg compared to wild-type neurons is reflected in a lower induction of c-Fos mRNA, lesser binding to AP-1 response element, as well as diminished induction of c-Fos nuclear immunoreactivity. Furthermore, transcriptional activation of the phase II antioxidant enzyme heme oxygenase-1, which is in part regulated by the AP-1 response element in its proximal promoter, is attenuated in Ngb-tg when compared to wild-type neurons challenged by similar excess of NO.

Excessive NO generated under pathophysiological conditions, is damaging and implicated in triggering various disease states including neurodegenerative processes [36, 37]. NO transverses cellular and mitochondrial membranes rapidly reacts with heme iron proteins and inhibits mitochondrial respiration primarily at respiratory complex IV [16]. Although, NO inhibition of oxygen binding at the active site of cytochrome c oxidase (ferrous heme aa3) is reversible, NO effectively prevents oxygen from accepting electrons, triggering reverse electron flow and formation of free radicals including the superoxide anion. Compartmentalized superoxide rapidly reacts with NO to form peroxynitrite that persists also after NO decay, damaging mitochondrial membranes, increasing proton leak and with sustained exposures compromising mitochondrial energy production [18, 38]. While, complex IV is generally considered the most sensitive mitochondrial target for NO interference, interference by NO at complex I [39] as well as depletion of mitochondrial ATP [40] have also been documented.

Important physiological processes for controlling escalating NO concentrations occur via interactions with oxygen transport proteins. Hemoglobin is considered the major sink of NO in endothelium [17] and similar function is attributed to myoglobin in heart and muscle [41]. Thus, both globins contribute to respiratory homeostasis in tissue-specific manner by effective elimination of NO from competition with oxygen at mitochondrial complex IV and evoke the possibility that neuroglobin might fulfill a similar role in neurons. Indeed, some studies have reported NO binding by neuroglobin [14, 42] and molecular dynamics simulation revealed strong stabilization of NO in all neuroglobin cavities, when compared to carbon monoxide and dioxygen [43], nonetheless, conclusive functional data and interpretation are still missing. Interestingly, a recent report showed improved survival in the presence of NO donors of Ngb overexpressing vector-transfected cells [34]. While, precise mechanisms underlying this ameliorative effect have not yet been identified, the possibility that NO binding by Ngb buffers damaging NO concentrations under pathological conditions is possible.

We previously reported neuroprotection by overexpressed Ngb in an in vivo mouse model of smoke inhalation [12]. Plausibly, during exposure to smoke the combination of reduced oxygen tension, toxic gases [44], exitotoxicity and activation of glial inducible nitric oxide synthase [45] is likely to shift the balance towards excessive production of superoxide and thereby intensify formation of peroxynitrite, consistently with substantial nitration of mitochondrial proteins that we have observed after inhalation of smoke [13]. In this context, any sequestration of surging NO should contribute to attenuation of smoke injury. To understand the mechanisms of protection by neuroglobin in a setting of excess NO, we asked whether the extent of impairment of specific mitochondrial activities by elevated NO, might differ in wild-type and Ngb-tg neurons. This stands to reason, given that in Ngb-tg neurons, overexpressed cytoplasmic neuroglobin might effectively reduce concentrations of NO molecules that reach the mitochondrial compartment, and thereby also reduce competition with oxygen at complex IV and subsequent burden of oxidative stress and respiratory compromise.

To compare the magnitude of NO effects in presence or absence of elevated neuroglobin, we used an in vitro setting, where NO was continually generated by slow-release donor added to culture medium [21] and critical mitochondrial parameters [32, 46] were assessed in real time. Measurements revealed substantial differences in mitochondrial functionality of Ngb-tg and wild-type neurons: a 50% reduction of baseline respiration in wild-type compared to a 30% reduction in Ngb-tg; a 40% increase in oxygen feeding into proton leak in wild-type versus 10% in Ngb-tg; about 70% reduction in spare respiratory capacity in wild-type versus only a 40% reduction in Ngb-tg. In combination, these differences reflect lesser extent of mitochondrial injury by sustained excess of NO in Ngb-tg neurons. These critical differences in the extent of mitochondrial impairments were registered by c-Fos gene, a key sensor of neuronal stress, which was induced to a significantly lesser extent of ~4-fold in Ngb-tg versus nearly 12-fold in wild-type neurons under these conditions. Furthermore, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) a phase II enzyme, which is downstream of c-Fos signaling, and binding of c-Fos/c-Jun heterodimer to its promoter contributes to HO-1 transcriptional regulation [47], was induced to a lesser degree (4-fold) in Ngb-tg when compared to wild-type (8-fold) neurons. Interestingly, no significant modulations of the investigated end points were detectable after a short, 3-h exposure to this concentration of NO (not shown), suggesting that changes detected after the 12-h exposure reflect progressive rather than acute mitochondrial injury.

c-Fos is an exquisitely sensitive sensor involved in detection of a broad range of modulations of neuronal homeostasis and activity [48, 49, 50, 51]. Notably, a recent study reported that in a mouse model of hypoxia, c-Fos response was exacerbated in the Ngb knockout mouse brain compared to wild-type, suggesting that Ngb deficiency lowers the threshold for hypoxic brain injury [52]. In addition, in that study, the expression of Hif-1a, a major sensor of oxygen tension was elevated to a greater degree in the Ngb knockout brain, revealing exacerbated severity of hypoxia in Ngb-deficient mouse brain [52]. This new evidence linking neuroglobin deficiency in the knockout mouse model with increased susceptibility to hypoxic injury, as registered by neuronal sensors, is in agreement with our observations, where upon NO challenge, c-Fos registers lesser neuronal stress when neuroglobin is abundant.

In summary, we have identified mitochondrial and cellular targets of NO, which are differentially affected in Ngb-tg and wild-type neurons. These include key mitochondrial respiratory activities and potential consequences of their modulations. Our data demonstrate that elevated neuroglobin raises the threshold of neuronal injury by NO, at least in part, via preservation of mitochondrial homeostasis and function.

Highlights.

Excess nitric oxide (NO) injures mitochondria and triggers neuronal degeneration.

Oxygen binding globin proteins in blood and muscle can sequester excessive NO.

Neuroglobin (Ngb) is a neuron-specific oxygen binding globin protein.

Overexpressed transgenic Ngb attenuates NO-induced mitochondrial impairments.

Hence, stress sensor genes are activated by NO to a lesser extent in Ngb neurons.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Shriners Hospitals for Children (8670) and the National Institutes of Health (ES014613 and NS034994) to EWE. We thank Eileen Figueroa and Steve Schuenke for help with manuscript preparation.

Abbreviations

- Ngb-tg

Neuroglobin transgene

- NO

nitric oxide

- OCR

oxygen consumption rate

- SRC

spare respiratory capacity

- FCCP

carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone

- DIV

day in vitro

- HO-1

heme oxygenase-1

- Syn-1

synapsin-1

- VDAC

voltage dependent anion channel

Footnotes

Authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Burmester T, Weich B, Reinhardt S, Hankeln T. A vertebrate globin expressed in the brain. Nature. 2000;407:520–523. doi: 10.1038/35035093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Droge J, Pande A, Englander EW, Makalowski W. Comparative genomics of neuroglobin reveals its early origins. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burmester T, Hankeln T. What is the function of neuroglobin? J Exp Biol. 2009;212:1423–1428. doi: 10.1242/jeb.000729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun Y, Jin K, Peel A, Mao XO, Xie L, Greenberg DA. Neuroglobin protects the brain from experimental stroke in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3497–3500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0637726100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan AA, Wang Y, Sun Y, Mao XO, Xie L, Miles E, Graboski J, Chen S, Ellerby LM, Jin K, Greenberg DA. Neuroglobin-overexpressing transgenic mice are resistant to cerebral and myocardial ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17944–17948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607497103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiger L, Tilleman L, Geuens E, Hoogewijs D, Lechauve C, Moens L, Dewilde S, Marden MC. Electron transfer function versus oxygen delivery: a comparative study for several hexacoordinated globins across the animal kingdom. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li W, Wu Y, Ren C, Lu Y, Gao Y, Zheng X, Zhang C. The activity of recombinant human neuroglobin as an antioxidant and free radical scavenger. Proteins. 2011;79:115–125. doi: 10.1002/prot.22863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brittain T, Skommer J. Does a redox cycle provide a mechanism for setting the capacity of neuroglobin to protect cells from apoptosis? IUBMB Life. 2012;64:419–422. doi: 10.1002/iub.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe S, Takahashi N, Uchida H, Wakasugi K. Human neuroglobin functions as an oxidative stress-responsive sensor for neuroprotection. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:30128–30138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.373381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hundahl CA, Fahrenkrug J, Hay-Schmidt A, Georg B, Faltoft B, Hannibal J. Circadian behaviour in neuroglobin deficient mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hundahl CA, Kelsen J, Dewilde S, Hay-Schmidt A. Neuroglobin in the rat brain (II): co-localisation with neurotransmitters. Neuroendocrinology. 2008;88:183–198. doi: 10.1159/000135617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee HM, Greeley GH, Jr, Englander EW. Transgenic overexpression of neuroglobin attenuates formation of smoke-inhalation-induced oxidative DNA damage, in vivo, in the mouse brain. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:2281–2287. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee HM, Reed J, Greeley GH, Jr, Englander EW. Impaired mitochondrial respiration and protein nitration in the rat hippocampus after acute inhalation of combustion smoke. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;235:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brunori M, Giuffre A, Nienhaus K, Nienhaus GU, Scandurra FM, Vallone B. Neuroglobin, nitric oxide, and oxygen: functional pathways and conformational changes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8483–8488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408766102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Doorslaer S, Dewilde S, Kiger L, Nistor SV, Goovaerts E, Marden MC, Moens L. Nitric oxide binding properties of neuroglobin. A characterization by EPR and flash photolysis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4919–4925. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210617200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill BG, Dranka BP, Bailey SM, Lancaster JR, Jr, Darley-Usmar VM. What part of NO don’t you understand? Some answers to the cardinal questions in nitric oxide biology. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:19699–19704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.101618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toledo JC, Jr, Augusto O. Connecting the chemical and biological properties of nitric oxide. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25:975–989. doi: 10.1021/tx300042g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moncada S, Bolanos JP. Nitric oxide, cell bioenergetics and neurodegeneration. J Neurochem. 2006;97:1676–1689. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piantadosi CA, Suliman HB. Redox regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:2043–2053. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larsen FJ, Schiffer TA, Weitzberg E, Lundberg JO. Regulation of mitochondrial function and energetics by reactive nitrogen oxides. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.08.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Almeida A, Almeida J, Bolanos JP, Moncada S. Different responses of astrocytes and neurons to nitric oxide: the role of glycolytically generated ATP in astrocyte protection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:15294–15299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261560998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kann O, Kovacs R. Mitochondria and neuronal activity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C641–657. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00222.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicholls DG. Oxidative stress and energy crises in neuronal dysfunction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1147:53–60. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong-Riley MT. Bigenomic regulation of cytochrome c oxidase in neurons and the tight coupling between neuronal activity and energy metabolism. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;748:283–304. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3573-0_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brewer GJ, Torricelli JR, Evege EK, Price PJ. Optimized survival of hippocampal neurons in B27-supplemented Neurobasal, a new serum-free medium combination. J Neurosci Res. 1993;35:567–576. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490350513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Swiercz R, Englander EW. Elevated metals compromise repair of oxidative DNA damage via the base excision repair pathway: implications of pathologic iron overload in the brain on integrity of neuronal DNA. J Neurochem. 2009;110:1774–1783. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06271.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh S, Englander EW. Nuclear depletion of apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (Ape1/Ref-1) is an indicator of energy disruption in neurons. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:1782–1790. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang YH, Borkan SC. Prior heat stress enhances survival of renal epithelial cells after ATP depletion. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:F1057–1065. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.270.6.F1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Englander EW, Wilson SH. Protein binding elements in the human beta-polymerase promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:919–928. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.4.919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abe Y, Sakairi T, Kajiyama H, Shrivastav S, Beeson C, Kopp JB. Bioenergetic characterization of mouse podocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299:C464–476. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00563.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brand MD, Nicholls DG. Assessing mitochondrial dysfunction in cells. Biochem J. 2011;435:297–312. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dranka BP, Benavides GA, Diers AR, Giordano S, Zelickson BR, Reily C, Zou L, Chatham JC, Hill BG, Zhang J, Landar A, Darley-Usmar VM. Assessing bioenergetic function in response to oxidative stress by metabolic profiling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1621–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jin K, Mao XO, Xie L, Khan AA, Greenberg DA. Neuroglobin protects against nitric oxide toxicity. Neurosci Lett. 2008;430:135–137. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gerencser AA, Neilson A, Choi SW, Edman U, Yadava N, Oh RJ, Ferrick DA, Nicholls DG, Brand MD. Quantitative microplate-based respirometry with correction for oxygen diffusion. Anal Chem. 2009;81:6868–6878. doi: 10.1021/ac900881z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bolanos JP, Herrero-Mendez A, Fernandez-Fernandez S, Almeida A. Linking glycolysis with oxidative stress in neural cells: a regulatory role for nitric oxide. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1224–1227. doi: 10.1042/BST0351224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gu Z, Nakamura T, Lipton SA. Redox reactions induced by nitrosative stress mediate protein misfolding and mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Mol Neurobiol. 2010;41:55–72. doi: 10.1007/s12035-010-8113-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Erusalimsky JD, Moncada S. Nitric oxide and mitochondrial signaling: from physiology to pathophysiology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2524–2531. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.151167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarti P, Arese M, Forte E, Giuffre A, Mastronicola D. Mitochondria and nitric oxide: chemistry and pathophysiology. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;942:75–92. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-2869-1_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brorson JR, Schumacker PT, Zhang H. Nitric oxide acutely inhibits neuronal energy production. The Committees on Neurobiology and Cell Physiology. J Neurosci. 1999;19:147–158. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00147.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flogel U, Merx MW, Godecke A, Decking UK, Schrader J. Myoglobin: A scavenger of bioactive NO. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:735–740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011460298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Herold S, Fago A, Weber RE, Dewilde S, Moens L. Reactivity studies of the Fe(III) and Fe(II)NO forms of human neuroglobin reveal a potential role against oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22841–22847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313732200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Orlowski S, Nowak W. Topology and thermodynamics of gaseous ligands diffusion paths in human neuroglobin. Biosystems. 2008;94:263–266. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee HM, Greeley GH, Herndon DN, Sinha M, Luxon BA, Englander EW. A rat model of smoke inhalation injury: influence of combustion smoke on gene expression in the brain. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;208:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ying-ying Z, Enci MK, Qiong C, Eng-ang L. Combustion smoke induced inflammation in the cerebellum and hippocampus of adult rats. Neuropathol Appli Neurobiol. Oct 29;(2–12) doi: 10.111/nan.12001. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yadava N, Nicholls DG. Spare respiratory capacity rather than oxidative stress regulates glutamate excitotoxicity after partial respiratory inhibition of mitochondrial complex I with rotenone. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7310–7317. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0212-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alam J, Cai J, Smith A. Isolation and characterization of the mouse heme oxygenase-1 gene. Distal 5′ sequences are required for induction by heme or heavy metals. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1001–1009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cui JK, Hsu CY, Liu PK. Suppression of postischemic hippocampal nerve growth factor expression by a c-fos antisense oligodeoxynucleotide. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1335–1344. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-04-01335.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cui J, Liu PK. Neuronal NOS inhibitor that reduces oxidative DNA lesions and neuronal sensitivity increases the expression of intact c-fos transcripts after brain injury. J Biomed Sci. 2001;8:336–341. doi: 10.1007/BF02258375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murphy M, Greferath U, Nag N, Nithianantharajah J, Wilson YM. Tracing functional circuits using c-Fos regulated expression of marker genes targeted to neuronal projections. Front Biosci. 2004;9:40–47. doi: 10.2741/1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Contestabile A. Regulation of transcription factors by nitric oxide in neurons and in neural-derived tumor cells. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;84:317–328. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hundahl CA, Luuk H, Ilmjarv S, Falktoft B, Raida Z, Vikesaa J, Friis-Hansen L, Hay-Schmidt A. Neuroglobin-deficiency exacerbates Hif1A and c-FOS response, but does not affect neuronal survival during severe hypoxia in vivo. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]