Abstract

Objective

To examine the relationship between adult attachment style and health risk behaviors among adult women in a primary care setting.

Methods

In this analysis of a population of women enrolled in a large health maintenance organization (N=701), we examined the relationship between anxious and avoidant dimensions of adult attachment style and a variety of sexual, substance-related, and other health risk behaviors. After conducting descriptive statistics of the entire population, we determined the relationships between the two attachment dimensions and health behaviors using multiple regression analyses in which we controlled for demographic and socioeconomic factors.

Results

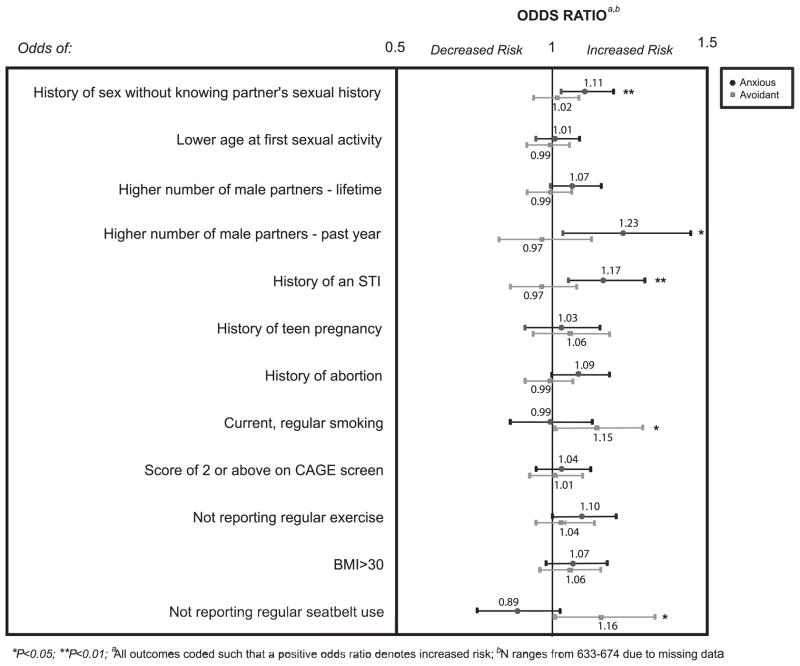

After adjustment for covariates, the anxious dimension of attachment style was significantly associated with increased odds of self-report of having sex without knowing a partner’s history, having multiple (≥2) male partners in the past year, and history of having a sexually transmitted infection (ORs [95% CIs]=1.11 [1.03, 1.20], 1.23 [1.04, 1.45]; and 1.17 [1.05, 1.30], respectively). The avoidant attachment dimension was associated with increased odds of being a smoker and not reporting regular seatbelt use (ORs [95% CIs]=1.15 [1.01, 1.30] and 1.16 [1.01, 1.33], respectively).

Conclusions

Both anxious and avoidant dimensions of attachment were associated with health risk behaviors in this study. This framework may be a useful tool to allow primary care clinicians to guide screening and intervention efforts.

Keywords: Attachment style, Health risk behaviors, Primary care

Introduction

Attachment theory, originally developed by John Bowlby, posits that through early relationships with caregivers infants develop cognitive “working models” that persist across the life course regarding their ability to elicit caregiving behavior from others and others’ responsiveness to their needs [1,2]. Adult attachment theory was later developed to describe the distinct patterns of interpersonal interactions that adolescents and adults display in romantic relationships [3–10]. Similar to infant attachment, “adult attachment style” is generally conceptualized as involving two dimensions which reflect an individual’s views of self and others. The anxious dimension of adult attachment reflects a person’s self-worth and their consequent degree of anxiety/vigilance concerning rejection and abandonment in relationships. Persons with high levels of attachment anxiety tend to have low self-esteem, seek emotional closeness, and rely heavily on others. In contrast, the avoidant dimension corresponds to one’s degree of discomfort with closeness and dependency; persons with high levels of attachment avoidance tend to be reticent about forming intimate relationships [11]. Some researchers have also used other approaches, including a categorical approach in which the two attachment dimensions are broken into four, mutually exclusive categories. In this approach, persons who have high degrees of anxiety but not avoidance are labeled “preoccupied”, persons with high degrees of avoidance but not anxiety are “dismissive”, persons with high degrees of both anxiety and avoidance are “fearful”, and persons who do not have high degrees of either anxiety or avoidance are “secure” [4].

In recent years, researchers have recognized the importance of a person’s attachment style in the context of non-romantic relationships, including relationships with health care providers [12,13]. Maladaptive approaches to relationships have been linked to a variety of health-related outcomes. For example, persons who score high on the anxious attachment dimension (i.e., who are preoccupied and/or fearful in the categorical model) tend to have high rates of health care utilization and associated costs [14], and are more likely to report having physical symptoms [14–16] compared with those with other styles of attachment. In contrast, persons with high rates of avoidance (i.e., who are dismissive and/or fearful in the categorical model) have trouble trusting health care providers [12,13], and as a consequence tend to be at higher risk of delaying care [17], missing health care appointments [18], and reporting poor adherence with preventive self-care recommendations in chronic disease [19–21]. In one study of diabetics, persons with an avoidant attachment style had an increased relative risk of dying in a 5-year period [22].

One area that is understudied at present is the contribution of adult attachment style to engagement in risk behaviors for diseases commonly seen in the primary care setting [23–26]. An increased understanding of the psychosocial correlates of these health risk behaviors could allow clinicians to identify patients at risk of acquiring lifestyle-related disease earlier, in order to better tailor prevention efforts. There is both theoretical and empirical evidence to support the idea that attachment style and a variety of health-related behaviors may be linked. From a theoretical perspective, in 2001 Maunder and Hunter proposed a model which suggests that insecure attachment may result in an increased use of “external regulators of affect” in place of more healthy strategies, along with the above-described influences it has on behavior in close relationships. This results in increased risk of several behavioral “disease risk factors” such as substance use, dysfunctional eating behaviors, and risky sexual behaviors [27]. Empirically, Dube, Felitti and colleagues have documented strong associations between exposure to early adverse childhood experiences and a variety of health behaviors (e.g., risky sexual behaviors, smoking, and problematic alcohol use) in multiple birth cohorts [28]. The research cited in the previous paragraph, furthermore, provides preliminary evidence that maladaptive attachment style may be in the pathway which produces this increase risk, in that it documents a relationship between maladaptive relational styles and a variety of lifestyle-related disease states. Indeed, associations have been detected in some samples between the anxious attachment dimension and correlates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unintended pregnancy, and substance-related disorders [29–40]. The avoidant attachment dimension has also been associated with a narrower, but important, array of health risk behaviors reflecting an avoidance of intimacy and/or use of external regulators of affect. These include having sex with casual/risky partners, and engaging in heavy alcohol use, smoking, and cocaine use [19,29–31,35,36,40–42].

Although this previous research clearly represents an important step toward understanding the contribution of attachment style to health risk behaviors, it is limited for several reasons. First, many of the above studies utilized samples that were small, specialized, or included participants within a narrow age range (e.g., adolescents and college students) [30–35,37–42]. In addition, many have generated conflicting results with respect to associations between avoidant attachment style and sexual and substance-related behaviors. Finally, these studies have tended to examine a narrow range of risk behaviors, contained almost exclusively in the sexual and substance-related dimensions. More research is therefore needed to understand the influences of attachment on health-related risk behaviors in primary care populations.

We sought to extend the above research by evaluating the association between anxious and avoidant dimensions of adult attachment style and risk behaviors for several of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States, using a sample of adult women enrolled in a health maintenance organization. We specifically sought to evaluate associations between attachment style and self-reported behavioral correlates of STIs, early/unintended pregnancy, substance use, cardiovascular disease, and injury in motor vehicle accidents (MVAs). We hypothesized that: 1.) the anxious dimension would be associated with increased odds of multiple risk behaviors occurring in the context of romantic/sexual relationships (i.e., of behaviors related to STI and unintended pregnancy risk) as well as increased odds of substance use, and 2.) the avoidant attachment dimension would be associated with increased odds of having had sex before knowing a partner’s sexual history, substance-related risk behaviors, and behaviors influenced by a lack of engagement in preventive self-care such as those that relate to risk of cardiovascular disease (i.e. weight control and a lack of regular exercise) and to a lack of regular seatbelt use in motor vehicles.

Methods

Study population

Participants were adult female members of Group Health Cooperative, a large health maintenance organization (HMO) who were recruited as part of an NIMH-funded study which aimed to explore associations between health care utilization, perceived health status, prior childhood maltreatment, and functional disability among adult women in a primary care setting (N=1225; age range 18 to 67 years) [43]. The present study involves data from the original wave of data collection (collected in 1995–96) and a follow up wave which took place three years later. In the follow-up wave, 1119 women from the original sample were contacted with an approach letter and a three-page questionnaire assessing the participant’s attachment style; 701 (63%) returned the questionnaire. When characteristics of responders and non-responders in the follow-up wave were compared, participants who responded were slightly older, were more likely to be white, and had a slightly higher educational and income level (see Ciechanowski et al., 2002 for details) [14]; however the sample characteristics still closely reflected the characteristics of the HMO population and geographic area from which the sample was drawn. Participants received a $3 token of appreciation for participating in the follow-up wave. All procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committees of the HMO and the University of Washington.

Variables

All outcomes were collected via self-report.

Attachment style

Two related instruments measuring attachment style were administered: the Relationship Scales Questionnaire (RSQ; 17-items) and the Relationship Questionnaire (RQ; 4-items). Both instruments are reliable and valid [4,44], and have been shown to be stable over periods of several years in adult populations [45–48]. Both questionnaires asked participants about their orientations in relationships in general (rather than using wording specific to romantic relationships; e.g., “I find it difficult to depend on other people.”) For both scales, we coded the scales such that a higher (more positive) score was associated with increased levels of the dimension (i.e., higher levels of anxious or avoidant attachment features). Cronbach’s alpha values in the present sample were 0.80, 0.64, and 0.86 for the RSQ, RQ, and all items from both questionnaires together, respectively. Based on a procedure recommended by the original authors of these instruments [49,50], RSQ and RQ results were combined for the present analyses by first computing continuous z-scored values for each of the 4 sub-scales of the individual questionnaires (i.e., secure, preoccupied, dismissive and fearful subscales), and then averaging these results. Anxious and avoidant attachment dimensions were then generated from the 4 subscales, also based on a procedure which developed by the original authors [51]. Since the final values for each attachment dimension were also z-scored, all odds ratios presented in the Results section reflect the relative increase in odds of a given outcome for every standard deviation change in attachment anxiety or avoidance.

Health risk behaviors

We evaluated a variety of self-report variables related to common causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States including risk of STI, early/unintended pregnancy, cardiovascular disease, and injury in an MVA [23–26]. All health risk behavior variables were coded in the direction of increased health risk (e.g., a variable related to exercise was coded as “lack of regular physical activity”). Specific variables included:

Ever having sex without knowing a partner’s history (Y/N)

Age at first sexual activity (divided into quartiles due to data distribution)

Number of male intercourse partners in lifetime (categorized as 0, 1, 2, 3, ≥4 due to data distribution)

Number of male intercourse partners in the past year (0–1, ≥2)

History of having one of the following STIs (genital warts, chlamydia, herpes, trichomonas, gonorrhea and/or pelvic inflammatory disease; Y/N)

History of teen pregnancy, defined as pregnancy prior to age 18 years (Y/N)

History of having an abortion (Y/N)

Current, regular smoking (defined as daily or more; Y/N)

Score on the CAGE alcohol screening instrument (categorized 0–1, ≥ 2 as is typical for this instrument) [52,53]

Lack of regular physical exercise, (defined as moderate or vigorous exercise at least once/week; Y/N)

Obesity (defined as body mass index ≥30 as per the standard definition of obesity from the Centers for Disease Control; Y/N) [54]

Lack of regular seat-belt use (defined as anything less than daily use while driving or riding in a car; Y/N).

Covariates

Covariates included age in years, race (white, African American, and other), marital status, household income ($0–$40,000 versus above), and highest level of education achieved (some college or less versus college graduate or more).

Analyses

Stata SE version 9 was used for all analyses. Descriptive statistics of demographic characteristics were computed for the entire study population as well as for subgroups above and below the median on both the anxious and avoidant attachment scales. We then computed unadjusted associations between the anxious and avoidant dimensions of attachment and each health behavior variable using logistic or ordinal logistic regression analyses (for binary and ordinal variables, respectively). For our main analyses, multiple logistic regressions were performed to determine whether the two attachment dimensions were significantly associated with the health risk behavior variables after adjusting for relevant covariates. We evaluated the two attachment dimensions simultaneously (i.e., in the same model) for each health behavior.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the study population are summarized in Table 1. Participants were, on average, 43.4 years (range 18–67 years) and were predominately white. About half were married. Over half of participants reported a household income above $40,000 per year, and a similar percentage reported having a college degree. The anxious scale was associated with significant differences in mean age, proportion with household income >$40,000, and demonstrated a borderline association with marital status and proportion with a college degree (i.e., p<.10). The avoidance scale was associated with all demographic variables except age (the association with “other race” was of borderline significance; p <.10).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study participants.

| Characteristic | Whole samplea | Anxious attachment

|

Avoidant attachment

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Above median | Below medianb | Above median | Below medianc | ||

| Age in years (mean (SD)) | 43.4 (10.8) | 41.6 (10.9) | 45.3 (10.4)*** | 43.6 (10.8) | 43.3 (10.9) |

| Race (%)d,e | |||||

| – White | 81.9 | 81.7 | 81.8 | 75.9 | 87.6*** |

| – African American | 4.3 | 5.2 | 3.5 | 6.7 | 2.0*** |

| – Other | 13.8 | 13.0 | 14.7 | 17.4 | 10.4† |

| Marital status | 53.6 | 49.3 | 57.8† | 45.8 | 61.2*** |

| % with annual household income >$40,000f | 59.4 | 55.0 | 63.7** | 53.1 | 65.5*** |

| % with college degreeg | 61.9 | 58.6 | 64.9† | 58.3 | 65.2** |

N=701 unless otherwise noted.

Significance level notations in this column indicates a significant association between the continuous anxious attachment dimension and each demographic variable.

Significance level notations in this column indicates the significance of an association between the continuous avoidant attachment dimension and each demographic variable.

N=697 due to missing data.

Categories do not always add up to 100% due to rounding error.

N=682 due to missing data.

N=699 due to missing data.

p<.10.

p<.01.

p<.001.

Unadjusted analyses revealed that a higher score on the anxious attachment dimension was significantly associated with increased odds of reporting multiple sexual and pregnancy-related variables including: having sex without knowing a partner’s history, having a lower age a first sexual activity, having a higher number of both lifetime male partners and male partners in the past year, and having had an abortion. It was also associated with increased odds of reporting a lack of engagement in regular physical exercise (all p-values<0.05; see Table 2). In contrast, having a higher score on the avoidant attachment dimension was associated with increased odds of reporting a pregnancy prior to age 18, being a current, regular smoker, being obese, and reporting both a lack of regular exercise and of seatbelt use. When results were adjusted for basic demographic and socioeconomic covariates, a higher score on the anxious attachment dimension remained significantly associated with odds of reporting having sex without knowing a partner’s history, having multiple male partners in the past year, and having had an STI; and a higher score on the avoidant attachment dimension remained significantly associated with increased odds of being a smoker and of not reporting regular seatbelt use (all p-values were again <0.05; see Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Unadjusted association between adult attachment style and health risk behaviors.

| Characteristic | Anxious (OR [95% CI])a | Avoidant (OR [95% CI])a |

|---|---|---|

| Sex without knowing partner’s sexual history (Y/N) | 1.14 [1.06, 1.23]*** | 1.03 [0.96, 1.10] |

| Lower age at first sexual activity (quartiles) | 1.07 [1.01, 1.15]* | 1.01 [0.95, 1.08] |

| Number of male partners – lifetime (0, 1, 2, 3, ≥4) | 1.10 [1.02, 1.18]* | 1.00 [0.94, 1.07] |

| Number of male partners – past year (0–1, ≥2) | 1.27 [1.11, 1.46]*** | 1.10 [0.96, 1.25] |

| Ever had an STI (Y/N) | 1.16 [1.05, 1.28]** | 0.99 [0.90, 1.09] |

| History of teen pregnancy (Y/N) | 1.06 [0.96, 1.18] | 1.13 [1.02, 1.25]* |

| Ever had an abortion (Y/N) | 1.09 [1.01, 1.18]* | 1.00 [0.93, 1.08] |

| Current, regular smoking (Y/N) | 1.08 [0.96, 1.22] | 1.21 [1.08, 1.36]** |

| Score on CAGE screen (0–1, ≥2) | 1.05 [0.97, 1.14] | 1.02 [0.94, 1.10] |

| Does not exercise regularly (Y/N) | 1.13 [1.03, 1.23]** | 1.10 [1.01, 1.20]* |

| Obese (Y/N) | 1.07 [0.98, 1.16] | 1.12 [1.03, 1.22]** |

| Does not use seatbelt regularly (Y/N) | 0.97 [0.85, 1.11] | 1.16 [1.02, 1.32]* |

N ranges from 652 to 695 for individual analyses due to missing data.

p<.05.

p<.01

p<.001.

Figure 1.

Association between adult attachment style and health risk behaviors after adjusting for covariates.

Discussion

Results of our unadjusted analyses were consistent with our first hypothesis, that the anxious dimension of attachment would be associated with increased risk sexual risk and substance-related variables; however when we adjusted for demographic covariates only the associations with sexual risk behaviors remained. Specifically, we found that adult women across a broad range of ages who displayed anxious attachment were at increased risk of reporting having had an STI as well as two related risk behaviors: having sex with a partner without knowing their sexual history and sex with multiple partners in the past year after adjustment for covariates. Other studies have demonstrated a similar association between the anxious attachment dimension (or the equivalent in other models of attachment style) and similar sexual health behaviors, as well as other high risk sexual behaviors such as decreased condom use, increased use of drugs or alcohol in conjunction with sexual activity, and increased risk of unwanted but consensual sexual experiences [29,30,34–39]. It may be that women with anxious styles of attachment may have difficulty engaging their partners in frank discussions related to negotiations around initiating sexual activity and condom use with partners. This theory has been posited and/or empirically tested by some previous researchers, who have evaluated the relationship between anxious attachment style and sexual risk behaviors in other populations such as adolescents, college students, pregnant women, and patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) [29,30,34,35,37–39]. This study suggests that the relationship between the anxious dimension of attachment and increased risky sexual behavior holds true among adult female primary care patients as well.

With respect to the avoidant dimension of attachment, after controlling for covariates our hypotheses were again partially supported. We found that the avoidant dimension was associated with increased odds of being a smoker and decreased odds of seatbelt use. The association with smoking is consistent with prior research [19,40]. Persons with high rates of avoidance tend to emphasize self-sufficiency and therefore may rely on (maladaptive) coping strategies that do not require reliance on others such as smoking to regulate negative emotions [27]. Furthermore, in comparison to individuals with lower levels of attachment avoidance, those with high levels may be less likely to request support from family members or providers around smoking cessation, or to, engage in smoking cessation programs that require accepting ongoing support from others [19]. The association between attachment avoidance and odds of not reporting regular seatbelt use has not been reported previously; similar to smoking this association may reflect this group’s rejection of the clear evidence and societal messages around the dangers of not using seatbelts [55] in favor of their own autonomy. Indeed, this group’s desire for self-reliance has been posited in other studies to explain a lack of engagement in recommended preventive self-care measures, which in at least one study was significant enough to put them at a higher risk of early mortality [19–22].

We did not find an association between the avoidant attachment dimension and any of the sexual or pregnancy-related variables in our main analyses. Among previous studies evaluating avoidant attachment style and its association with these relationship-oriented behaviors, the most consistent finding related to an association between the avoidant dimension of attachment and sexual behavior was an association with variables reflecting having had risky or casual partners [29,30]. We studied one variable related to partner type (odds of ever having sex with a partner without knowing their sexual history) and did not find an association with avoidant attachment. It is important to note that some other previous studies which have evaluated partner type variables have failed to find associations as well [37–39]. In addition, the two studies which did detect an association were conducted among college students who are at an age developmentally when there may be wider variation in sexual experiences, compared with our more mature population [29,30]. It may be that in our sample, in which participants were on average decades older than those studied previously, it was more normative to have had a history of having sex with a partner before knowing their sexual history at some point during the life course. Future studies should evaluate the influence of this attachment dimension and a broader range of variables related to partner choice and other sexual risk behaviors in primary care settings. This research should ideally include participants at a variety of ages, given the difference between our results and those found in studies involving primarily college-age participants.

Finally, although we hypothesized that both dimensions of attachment would be associated with increased risk of substance-related behaviors, neither dimension was associated with score on the CAGE screen in this study. Previous studies have detected associations between both types of insecure attachment and drinking and/or drug use [29,31–33,35,39,41,42]. Similar to our discussion related to sexual behavior, this may be due to the fact that we evaluated an older population than these previous studies. It is possible that later in life, factors other than relationship style predict risk of substance use. In contrast, attachment style may play a larger role when young women are in a phase of their lives in which substance use tends to be influenced by a person’s competence in and degree of support from relationships with peers (i.e., when they are in their teens and/ or early 20s) [29,31].

All of the above health risk behaviors which we found to be significantly related to attachment style have been shown to be potentially modifiable using brief intervention techniques in primary care settings [56–61]. Although there is need for confirmation of our findings in other primary care samples, these results in combination with those from previous studies suggest that attachment style may be a useful framework for anticipating risk factors for a variety of common contributors to morbidity and mortality among adult women in this setting [23–26]. Specifically, an understanding of the influence of attachment style could be used to augment existing screening practices and allow practitioners or other team members (e.g., social workers, case managers, or therapists) to more quickly identify relationship-based risk factors for disease among persons with high levels of anxious attachment (e.g. sexual behaviors that place them at higher risk of STIs or unwanted pregnancy). It could also be used to help providers recognize when patients with high levels of avoidant attachment are using unhealthy strategies such as smoking to regulate negative emotions and/or are non-compliant with preventive/self-care recommendations (e.g., when they are not using seatbelts or adhering to chronic disease treatment guidelines) [27,62].

This research and more generally the concept of attachment style variations may also help us to reconsider the effectiveness of specific interventions targeted at reducing the above risk behaviors in primary care settings, especially when they require collaboration with others in order to be successful. Attachment style has been shown to influence both patient satisfaction and outcomes in at least one intervention delivered in a primary care setting (i.e., in a trial evaluating a flexible, collaborative intervention to reduce depressive symptoms in diabetic patients) [63]. Given a choice of an intervention that requires interactions with others to make changes versus “solo” solutions (i.e., reading educational material, viewing a video), it may be useful in clinical settings to consider the likelihood of uptake of varying solutions in individuals with higher levels of anxious and/or avoidant attachment style. For instance, persons with high degrees of anxious attachment may benefit from interventions that focus on interactive skill and self-esteem building exercises, particularly ones which are focused on improving communication and negotiation skills with romantic and/or sexual partners [38]. In contrast, persons with high degrees of avoidant attachment may engage better in interventions targeting smoking cessation and/or injury prevention that do not involve a high degree of interpersonal collaboration/trust, which are self-directed, and/or which allow some degree of choice as these methods would allow them to preserve their sense of autonomy. In above-mentioned depression trial [63], persons with high degrees of avoidance actually had greater improvement in their depressive symptoms as well as greater levels of satisfaction compared with those who had anxious orientations, which authors attribute to the flexibility of the intervention (such as choice of telephone or in-person follow up visits). Examples of other types of intervention strategies tailored to persons with high levels of avoidance might include pamphlets, DVDs, and online resources that they could read on their own.

We would like to acknowledge several limitations. This study contained a sample of primarily white adult women in an HMO, due to the fact that these were the characteristics of the sample included in the original parent study. Relationships between attachment style and health risk behaviors may vary by gender, race, or ethnicity, and may also be different if examined in a less economically stable population. In addition, we did not include variables reflecting mental health or other personality factors which would be likely influence engagement in health risk behaviors as covariates; thus it is possible that the associations we detected could be related to a third, unmeasured factor. We would also like to acknowledge the non-response bias noted in the methods section (i.e., that there were several minor but statistically significant differences between respondents and non-respondents in the second wave of data collection for this study) which could have influenced the relationships (or lack thereof) that we detected between our exposure and outcomes variables. It is also theoretically possible that attachment style changed significantly in the three years between the first and second wave of data collection, although studies examining the stability of attachment style over the life course suggest that large changes over this time period are unlikely [45–48].

Another important potential limitation is that all variables were self-report in nature; participants may therefore have underreported their participation in the health risk behaviors we evaluated, or misrepresented their attachment orientation as compared to what would be assessed by an observer. However, while not a perfect tool clinical medicine necessarily relies on self-report data, and self-reports of both risk behaviors and attachment style have been associated with a variety of disease related outcomes [20,22,52,53,64]. Thus, we feel that our results still provide important information for clinicians. This study was also cross-sectional which limits our ability to comment on causality. Some variables were measured retrospectively as well, and were likely remote for a sizeable proportion of study participants (e.g., teen pregnancy, age at first sexual activity). It is possible that if the relationship between attachment style and these variables were examined prospectively that associations would be found. Some may also consider it a limitation that we did not correct for multiple comparisons, however we would like to note that this decision was intentional due to our hypothesis that the anxious and avoidant attachment dimensions would each be associated with unique patterns of health risk behaviors. Finally, these data were collected over a decade ago. It is possible and even likely that due to secular trends, rates of some of the risk behaviors examined in this study have changed over time (e.g. increased seatbelt use due to stronger seatbelt legislation in many states); however these behaviors are still clearly important contributors to morbidity and mortality at present [23,65], and it is unlikely that the relationships between adult attachment style and health risk behaviors have changed significantly during this time period.

In summary, both anxious and avoidant attachment dimensions were associated with important health risk behaviors in this study. We conclude that if these relationships are confirmed in future studies involving primary care populations, adult attachment style may be an effective framework which providers could use to efficiently direct screening and intervention efforts in the context of busy practices.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Edward A. Walker, principal investigator of the original parent study from which these data were taken as well as the Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, Seattle, WA. We also wish to acknowledge support from the following grants: Dr. Ahrens — NIH T32 # 5T32MH02002, NIH K23 # 1K23MH90898-01A1, and a University of Washington Center for AIDS Research New Investigator Award (this center is supported by NIH grant # P30AI027757); Dr. Katon — NIH K24 # 5K24MH069741.

References

- 1.Ainsworth MS. Attachments beyond infancy. Am Psychol. 1989;44:709–16. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowlby J. A secure base: parent–child attachment and healthy human development. New York, NY US: Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartholomew K. Avoidance of intimacy: an attachment perspective. J Soc Pers Relat. 1990;7:147–78. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61:226–44. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan KA, Shaver PR. Dimensions of adult attachment, affect regulation, and romantic relationship functioning. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1995;21:267–83. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins NL, Read SJ. Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;58:644–63. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.4.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crowell JA, Fraley RC, Shaver PR, Cassidy J. Handbook of attachment: theory, research, and clinical applications. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 1999. Measurement of individual differences in adolescent and adult attachment; pp. 434–65. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fraley RC, Spieker SJ. Are infant attachment patterns continuously or categorically distributed? A taxometric analysis of strange situation behavior. Dev Psychol. 2003;39:387–404. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraley RC, Waller NG, Brennan KA. An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78:350–65. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;52:511–24. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffin DW, Bartholomew K. Models of the self and other: fundamental dimensions underlying measures of adult attachment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:430–45. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maunder RG, Hunter JJ. Assessing patterns of adult attachment in medical patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:123–30. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson D, Ciechanowski PS. Attaching a new understanding to the patient–physician relationship in family practice. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16:219–26. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ciechanowski PS, Walker EA, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Attachment theory: a model for health care utilization and somatization. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:660–7. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000021948.90613.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tasca G, Balfour L, Ritchie K, Bissada H. Change in attachment anxiety is associated with improved depression among women with binge eating disorder. Psychotherapy. 2007;44:423–33. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.44.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tasca GA, Szadkowski L, Illing V, Trinneer A, Grenon R, Demidenko N, et al. Adult attachment, depression, and eating disorder symptoms: the mediating role of affect regulation strategies. Pers Individ Differ. 2009;47:662–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sullivan MD, Ciechanowski PS, Russo JE, Soine LA, Jordan-Keith K, Ting HH, et al. Understanding why patients delay seeking care for acute coronary syndromes. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:148–54. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.825471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ciechanowski P, Russo J, Katon W, Simon G, Ludman E, Von Korff M, et al. Where is the patient? The association of psychosocial factors and missed primary care appointments in patients with diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciechanowski P, Russo J, Katon W, Von Korff M, Ludman E, Lin E, et al. Influence of patient attachment style on self-care and outcomes in diabetes. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:720–8. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000138125.59122.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ciechanowski PS, Hirsch IB, Katon WJ. Interpersonal predictors of HbA(1c) in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:731–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.4.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE, Walker EA. The patient–provider relationship: attachment theory and adherence to treatment in diabetes. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:29–35. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ciechanowski P, Russo J, Katon WJ, Lin EH, Ludman E, Heckbert S, Von Korff M, Williams LH, Young BA. Relationship styles and mortality in patients with diabetes. Diab Care. 2010;33:539–44. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu J, Kochanek MA, Murphy SL, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: final data for 2007. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2010;58 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Report: government STD prevention effort underfunded, off-target. Vol. 23. Nation’s Health; 1993. p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Deaths: preliminary data for 2006. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2008;56(6) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cates JR, Herndon NL, Schulz SL, Darroch JE. Our voices, our lives, our futures: youth and sexually transmitted diseases. Chapel Hill, NC: School of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maunder RG, Hunter JJ. Attachment and psychosomatic medicine: developmental contributions to stress and disease. Psychosom Med Jul-Aug. 2001;63(4):556–67. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Giles WH, Anda RF. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on health problems: evidence from four birth cohorts dating back to 1900. Prev Med Sep. 2003;37(3):268–77. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooper ML, Shaver PR, Collins NL. Attachment styles, emotion regulation, and adjustment in adolescence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74:1380–97. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gentzler AL, Kerns KA. Associations between insecure attachment and sexual experiences. Pers Relat. 2004;11:249–65. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caspers KM, Cadoret RJ, Langbehn D, Yucuis R, Troutman B. Contributions of attachment style and perceived social support to lifetime use of illicit substances. Addict Behav. 2005;30:1007–11. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kassel JD, Wardle M, Roberts JE. Adult attachment security and college student substance use. Addict Behav. 2007;32:1164–76. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McNally AM, Palfai TP, Levine RV, Moore BM. Attachment dimensions and drinking-related problems among young adults the meditational role of coping motives. Addict Behav. 2003;28:1115–27. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feeney JA, Kelly L, Gallois C, Peterson C, Terry DJ. Attachment style, assertive communication, and safer-sex behavior. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1999;29:1964–83. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feeney JA, Peterson C, Gallois C, Terry DJ. Attachment style as a predictor of sexual attitudes and behavior in late adolescence. Psychol Health. 2000;14:1105–22. doi: 10.1080/08870440008407370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sales JM, Latham TP, Diclemente RJ, Rose E. Differences between dual-method and non-dual-method protection use in a sample of young African American women residing in the southeastern United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:1125–31. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ciesla JA, Roberts JE, Hewitt RG. Adult attachment and high-risk sexual behavior among HIV-positive patients. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2004;34:108–24. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kershaw TS, Milan S, Westdahl C, Lewis J, Rising SS, Fletcher R, et al. Avoidance, anxiety, and sex: the influence of romantic attachment on HIV-risk among pregnant women. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:299–311. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9153-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Syren-Vitullo DA. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. Vol. 55. US: ProQuest Information & Learning; 1994. The relationship between attachment style and sexual risk behaviors related to HIV infection; p. 1655. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lyvers M, Thorberg FA, Dobie A, Huang J, Reginald P. Mood and interpersonal functioning in heavy smokers. J Subst Use. 2008;13:308–18. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doumas DM, Turrisi R, Wright DA. Risk factors for heavy drinking and associated consequences in college freshmen: athletic status and adult attachment. Sport Psychol. 2006;20:419–34. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vungkhanching M, Sher KJ, Jackson KM, Parra GR. Relation of attachment style to family history of alcoholism and alcohol use disorders in early adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;75:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walker EA, Gelfand A, Katon WJ, Koss MP, Von Korff M, Bernstein D, et al. Adult health status of women with histories of childhood abuse and neglect. Am J Med. 1999;107:332–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00235-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Griffin DW, Bartholomew K, Perlman D. Attachment processes in adulthood. London England: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1994. The metaphysics of measurement: the case of adult attachment; pp. 17–52. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kirkpatrick LA, Hazan C. Attachment styles and close relationships: a four-year prospective study. Pers Relat. 1994;1:123–42. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamilton CE. Continuity and discontinuity of attachment from infancy through adolescence. Child Dev. 2000;71:690–4. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Waters E, Merrick S, Treboux D, Crowell J, Albersheim L. Attachment security in infancy and early adulthood: a twenty-year longitudinal study. Child Dev. 2000;71:684–9. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klohnen EC, John OP, Simpson JA, Rholes WS. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 1998. Working models of attachment: a theory-based prototype approach; pp. 115–40. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bartholomew K, Shaver PR. Methods of assessing adult attachment: do they converge? In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York: Guilford; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ognibene TC, Collins NL. Adult attachment styles, perceived social support and coping strategies. J Soc Pers Relat. 1998;15:323–45. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kurdek LA. On being insecure about the assessment of attachment styles. J Soc Pers Relat. 2002;19:811–34. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smart RG, Adlaf EM, Knoke D. Use of the CAGE scale in a population survey of drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 1991;52:593–6. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bisson J, Nadeau L, Demers A. The validity of the CAGE scale to screen for heavy drinking and drinking problems in a general population survey. Addiction. 1999;94:715–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9457159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults—the evidence report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6(Suppl 2):51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thomas J. Road traffic accidents before and after seatbelt legislation—study in a district general hospital. J R Soc Med. 1990;83:79–81. doi: 10.1177/014107689008300207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB, Hutchinson MK, Cederbaum JA, O’Leary A. Sexually transmitted infection/HIV risk reduction interventions in clinical practice settings. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2008;37:137–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Searight R. Realistic approaches to counseling in the office setting. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79:277–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Williams SB, Whitlock EP, Edgerton EA, Smith PR, Beil TL. Counseling about proper use of motor vehicle occupant restraints and avoidance of alcohol use while driving: a systematic evidence review for the U.S Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:194–206. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-3-200708070-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grimshaw GM, Stanton A. Tobacco cessation interventions for young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD003289. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003289.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lawton BA, Rose SB, Raina Elley C, Dowell AC, Fenton A, Moyes SA. Exercise on prescription for women aged 40–74 recruited through primary care: two year randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:120–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Armit CM, Brown WJ, Marshall AL, Ritchie CB, Trost SG, Green A, et al. Randomized trial of three strategies to promote physical activity in general practice. Prev Med. 2009;48:156–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ciechanowski PS. As fundamental as nouns and verbs? Towards an integration of attachment theory in medical training. Med Educ. 2010;44:122–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ciechanowski PS, Russo JE, Katon WJ, Korff MV, Simon GE, Lin EH, et al. The association of patient relationship style and outcomes in collaborative care treatment for depression in patients with diabetes. Med Care. 2006;44:283–91. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000199695.03840.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Okura Y, Urban LH, Mahoney DW, Jacobsen SJ, Rodeheffer RJ. Agreement between self-report questionnaires and medical record data was substantial for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke but not for heart failure. J Clin Epidemiol Oct. 2004;57(10):1096–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2007. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]