Abstract

Background

Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) was initially identified as a key receptor interacting protein 3 downstream component of tumor-necrosis-factor-induced necrosis. In this study, we characterized the expression of MLKL in ovarian carcinomas and evaluated the prognostic value of MLKL in patients with ovarian cancer.

Materials and methods

The ovarian cancer tissue specimens were collected from 153 patients diagnosed as primary ovarian cancer after operation at The Second Xiangya Hospital from January 2005 to December 2008. Immunohistochemistry was performed for MLKL and the protein expression score was quantified using an established scoring system. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated for disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) for all patients. MLKL expression levels were correlated with DFS and OS using univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis.

Results

Seventy-five patients (49%) were defined as having high MLKL expression and 67 patients (43.7%) had >80% of cells staining for MLKL. Remarkably, low MLKL expression was significantly associated with decreased DFS (median 40 months versus 25 months, P=0.0282) and OS (median 43 months versus 28 months, P=0.0032). In multivariate analysis, retained significance was also observed.

Conclusion

Low MLKL expression was significantly associated with both decreased DFS and OS in patients with primary ovarian cancer. MLKL expression may serve as a potential prognostic marker in patients with ovarian cancer.

Keywords: MLKL, ovarian cancer, prognostic value

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer deaths in women, and it is the third most common gynecological cancer.1 In the People’s Republic of China, the age-standardized incidence and mortality rates of ovarian cancer are 3.4 and 1.6 per 100,000, respectively.2 Despite advances in surgical resections and systemic chemotherapies, the prognosis of ovarian cancer remains poor and the 5-year survival rate is only approximately 30% after the initial diagnosis.3 The main reason for the poor rate of survival is that early symptoms of malignant ovarian tumors are silent and most of the patients have an advanced stage of the disease at diagnosis. In addition, primary or secondary multidrug resistances also account for failure in treatment of ovarian cancer.4 Thus, identifying novel molecular markers with prognostic value is important for improving therapeutic methods and extending survival of ovarian cancer patients.

Necrosis is a type of cell death and is morphologically characterized by a gain in cell volume, swelling of organelles, plasma membrane rupture, and subsequent loss of intracellular contents.5 Necrosis is often observed in solid tumors with overgrowth and many cancer treatments can induce necrotic cell death.6,7 Necrosis can occur in a controlled and regulated manner, which is called necroptosis.8 The initiation of necroptosis can be induced through death receptors including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor 1, TNF receptor 2, and cluster of differentiation 95 (FasR). The serine/threonine kinases, receptor-interacting protein 1 (RIP1), and receptor-interacting protein 3 (RIP3) are key regulators of necrotic signaling.8 The mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) has been recently identified as a key RIP3 downstream component of TNF-induced necrosis.9,10 MLKL is phosphorylated by RIP3 and is recruited to the necrosome through its interaction with RIP3. In addition, it has been shown that prolonged c-Jun N terminal kinase activation contributes to TNF-induced necrosis.11 Several studies demonstrated that the activation of c-Jun N terminal kinase is associated with poor prognosis in cancer patients.12,13 However, the prognostic values of RIP1 and RIP3, the key components of the necroptosis pathway, have not been evaluated in cancer patients. Interestingly, a recent study suggested that MLKL expression can serve as a potential prognostic biomarker for patients with early-stage resected pancreatic cancer.14 However, the prognostic value of MLKL in other types of cancers and the role of MLKL in cancer necroptosis is unknown. In this study, we investigate the expression and prognostic value of MLKL in patients with ovarian cancer.

Materials and methods

Patients

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of The Second Xiangya Hospital, Hunan, People’s Republic of China. Informed consent was obtained from all of the patients. The ovarian cancer tissue samples were collected from 153 patients diagnosed with primary ovarian cancer after operation at The Second Xiangya Hospital from January 2005 to December 2008. All of the ovarian cancer patients received cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapies following cytoreduction. Briefly, the patients were treated with paclitaxel (135 mg/m2, intravenous [IV] for 3 hours) plus cisplatin (70 mg/m2, IV for 1 hour) and repeated every 21 days for six cycles. Surgical staging was established according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) system. Histopathological classification, including the stage, grade, and tumor type, was performed by an experienced pathologist (Table 1). Disease-free survival (DFS) was calculated from the date of the first cycle of first-line chemotherapy to the first radiological evidence of recurrence. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of histological diagnosis to the date of cancer-caused death or to the date of the last follow-up examination.

Table 1.

Clinic pathological characteristics and results of MLKL immunohistochemistry

| Characteristics | Number of patients | MLKL expression

|

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low or no | High | |||

| Ages | 0.1412 | |||

| ≤60 | 62 | 27 | 35 | |

| >60 | 91 | 51 | 40 | |

| Histologic type | 0.0782 | |||

| Serous | 93 | 42 | 51 | |

| Mucinous | 42 | 28 | 14 | |

| Endometrioid | 12 | 5 | 7 | |

| Clear cell | 6 | 3 | 3 | |

| Pathological grade | 0.1353 | |||

| 1 | 25 | 17 | 8 | |

| 2 | 44 | 19 | 25 | |

| 3 | 84 | 42 | 42 | |

| FIGO stage | 0.0906 | |||

| I–II | 57 | 24 | 33 | |

| III–IV | 96 | 54 | 42 | |

Abbreviations: FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; MLKL, mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded tissues were stained with anti-MLKL antibody (1:60 dilution, ab118348; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) at 4°C overnight. Rabbit immunoglobulin G was used as a negative control. After washing three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the slides were incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody (1:200 dilution; Vector Laboratories Inc, Burlingame, CA, USA) at room temperature for 30 minutes. After washing three times with PBS, the slides were stained with the ABC Elite kit (Vector Laboratories Inc). Finally, the slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, cleared, and then mounted with Permount mounting medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Histological images were captured from the microscope (Carl Zeiss AX10; Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany) with an objective magnification of X40, and high-resolution digital images were acquired and processed with Axionvision software (Carl Zeiss Meditec AG). MLKL staining was scored independently by two pathologists and was calculated using a previously defined scoring system.15,16 Briefly, the proportion of positive tumor cells was scored as: 0= less than 5%; 1+=5%–20%; 2+=21%–50%; and 3+>50%. The intensity was arbitrarily scored as 0= weak (no color or light blue), 1= moderate (light yellow), 2= strong (yellow brown), and 3= very strong (brown). The overall score was calculated by multiplying the two scores obtained from each sample. A score of ≥4 was defined as high MLKL expression and a score of <4 was defined low MLKL expression.

Statistical analysis

The relationship between the expression of MLKL and patient’s age, histological type, pathologic grade, and FIGO stage were analyzed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. OS curves and DFS curves were generated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using a log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using Cox regression models. P-values less than 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. Data were analyzed using the SPSS (version 20.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) software program.

Results

In this study, we collected a total of 153 ovarian cancer samples from patients with a median age of 66 years. Patient characteristics of the population are summarized in Table 1. A total of 60.7% of the cases had a serous histology (93/153); 27.4% of the cases had a mucinous histology (42/153); whereas endometrioid and clear cell histotypes were less represented. The median follow-up for survivors was 37 months (range, 3–102 months). At the time of the last follow-up, 71.8% of the patients had died and 15.4% had no evidence of disease. All of the patients in this study were treated with cisplatin-based first-line chemotherapy after surgery.

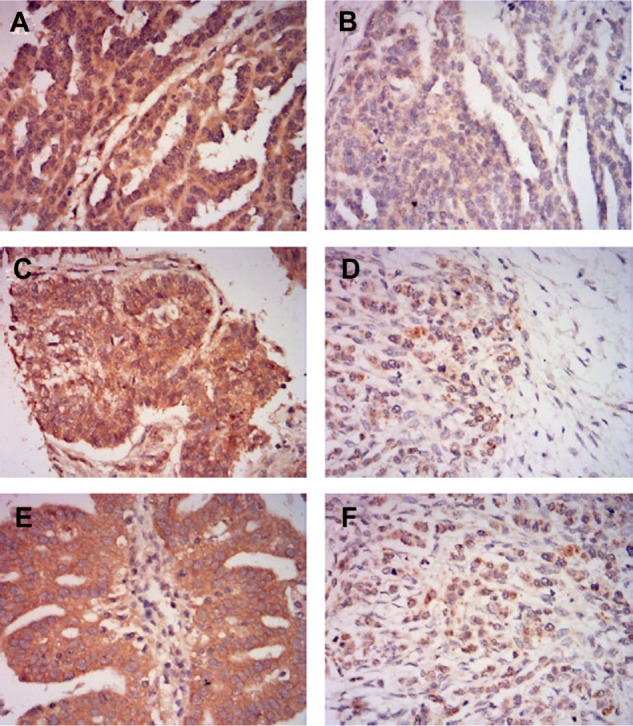

We examined the expression of MLKL in ovarian tumor samples by immunohistochemical analysis. As shown in Figure 1, MLKL positive staining was localized to the cytoplasm in tumor cells. According to established criteria for high-expression and low-expression groups, 75 patients (49%) were defined as having high MLKL expression (Table 1) and 67 patients (43.7%) had >80% of cells staining for MLKL. We further analyzed the association of MLKL expression with clinic pathological characteristics in the patients. We found no statistical associations between the expression of MLKL and patient age, histological type, pathologic grade, or FIGO stage (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Representative images of MLKL immunohistochemical staining in ovarian cancer tissues.

Notes: (A) High MLKL expression in serous ovarian cancer tissue. (B) Low MLKL expression in serous ovarian cancer tissue. (C) High MLKL expression in mucinous ovarian cancer tissue. (D) Low MLKL expression in mucinous ovarian cancer tissue. (E) High MLKL expression in endometrioid ovarian cancer tissue. (F) Low MLKL expression in endometrioid ovarian cancer tissue. Magnification, ×400.

Abbreviation: MLKL, mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein.

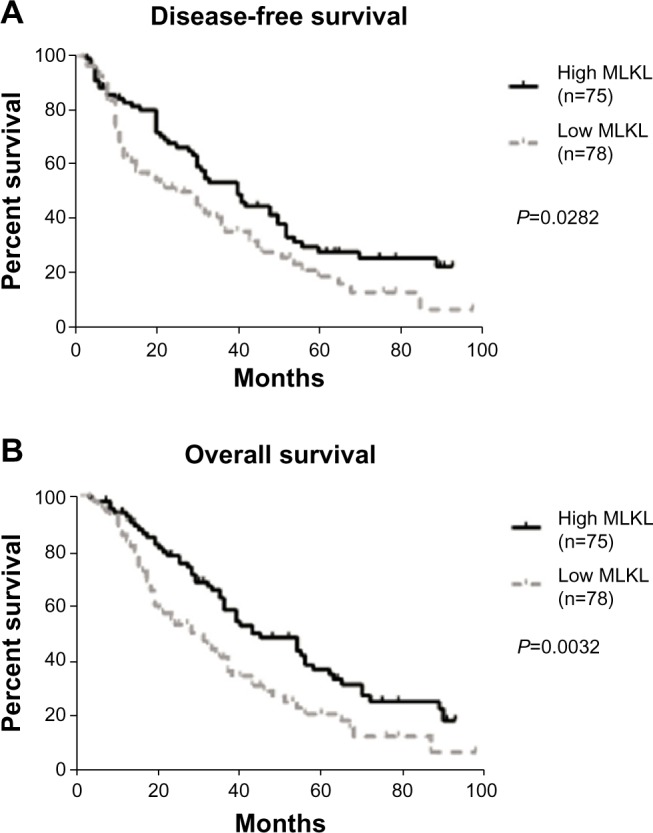

We then evaluated the prognostic significance of MLKL expression in ovarian cancer patients. Interestingly, we found that high MLKL expression was significantly associated with increased DFS (median 40 months versus 25 months, P=0.0282) and showed a trend towards longer OS (median 43 months versus 28 months, P=0.0032) (Figure 2A and B). Furthermore, a multivariate Cox regression analysis was applied to all of the clinicopathologic characteristics with MLKL expression levels. As shown in Table 2, low MLKL expression levels were independently associated with the poor prognosis of patients with ovarian cancer.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier log-rank survival analysis for (A) disease-free survival and (B) overall survival of ovarian cancer patients according to MLKL expression.

Abbreviations: MLKL, mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein; n, number.

Table 2.

Multivariate analyses for all patients (n=153)

| Characteristics | DFS

|

OS

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Ages (≤60 years vs >60 years) | 1.2 (0.8–2.1) | 0.1281 | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | 0.4586 |

| Histologic type (serous vs mucinous vs endometrioid vs clear cell) | 1.5 (0.4–1.5) | 0.0926 | 0.8 (0.2–1.7) | 0.8192 |

| Pathological grade (grade 1 vs grade 2 vs grade 3) | 1.3 (0.9–2.0) | 0.2565 | 1.0 (0.8–1.4) | 0.1328 |

| FIGO stage (I–II vs III–IV) | 0.8 (0.6–1.9) | 0.2734 | 0.6 (0.2–1.7) | 0.0937 |

| Level of MLKL expression (high vs low) | 3.5 (0.5–7.1) | 0.0211 | 4.2 (1.3–11.5) | 0.0038 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DFS, disease-free survival; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; HR, hazard ratio; MLKL, mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein; OS, overall survival; vs, versus.

Discussion

MLKL was initially identified as a key mediator in TNF-induced necroptosis. In cancer cells, RIP3 interacts with and phosphorylates MLKL to promote necroptosis.9,10 Interestingly, one recent study suggested that MLKL expression can be served as a prognostic biomarker in patients with early-stage resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma.14 In this study, Colbert et al identified that low MLKL expression was significantly associated with both decreased DFS and OS in the patients receiving adjuvant therapy. This study provides the first evidence that a necroptosis protein has prognostic value in cancer patients. In our current study, by using a relatively large cohort of ovarian carcinoma specimens, we identified that ovarian cancer patients with low MLKL expression showed a worse DFS and OS, which is similar to the pattern described by Colbert et al.14 It has been shown that cisplatin can induce both apoptosis and necrosis in cancer cells, which is dependent on the profile of proteins involved in cell death and cell cycle.17,18 Because MLKL was a key mediator in necroptosis signaling, low expression of MLKL may suggest decreased necroptosis signaling in patients with chemotherapy. Thus, one possible underlying mechanism for the association of low MLKL expression with poor prognosis in ovarian cancer patients may be a result of decreased necroptosis signaling in these patients. In the future, it would be interesting to examine the necroptosis-specific phosphorylation level of MLKL in cancer patients in order to validate the role of MLKL in necroptosis in cancer patients with chemotherapy.

As all of the patients in our study received cisplatin-based chemotherapy, our study provides a potential biomarker for clinicians to better select chemotherapies based on MLKL expression. Patients with low MLKL expression in tumor tissues may be less likely to benefit from the regular cisplatin-based chemotherapy. However, these patients may benefit from combination chemotherapy or participation in clinical trials. Thus, future studies should examine the role of MLKL in predicting response to different therapies for better treatment selection. Recently, there have been reports of several other proteins that may serve as a prognosis biomarker for ovarian cancer patients such as steroid receptor coactivator-3, high-mobility group AT-hook 2, c-Abl, and centromere protein A.16,19–21 These proteins have been shown to be involved in cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, invasion, and metastasis in cancer. Our study demonstrated that expression of a protein involved in necroptosis exhibits prognostic value in ovarian cancer patients, suggesting that necroptosis may play an important role in determining cancer cell death and patient outcome with chemotherapy. Future studies need to evaluate the association between MLKL and other prognostic biomarkers and may identify a prognostic panel including multiple prognostic biomarkers in ovarian cancer patients.

In conclusion, our study first explored the expression of MLKL in the context of ovarian cancer and suggests that low MLKL expression is associated with decreased DFS and OS in patients with ovarian cancer. This study suggests that MLKL may serve as a potential therapeutic target in ovarian cancer patients. However, since relatively little is known about the detailed role of MLKL in necroptosis or in other signaling pathways, future studies need to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of MLKL in cancer cell death with chemotherapy.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (number 2013SK3045).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim K, Zang R, Choi SC, Ryu SY, Kim JW. Current status of gyneco-logical cancer in China. J Gynecol Oncol. 2009;20(2):72–76. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2009.20.2.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thigpen T, duBois A, McAlpine J, et al. Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup First-line therapy in ovarian cancer trials. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21(4):756–762. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31821ce75d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaughan S, Coward JI, Bast RC, Jr, et al. Rethinking ovarian cancer: recommendations for improving outcomes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(10):719–725. doi: 10.1038/nrc3144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zong WX, Thompson CB. Necrotic death as a cell fate. Genes Dev. 2006;20(1):1–15. doi: 10.1101/gad.1376506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vanlangenakker N, Vanden Berghe T, Vandenabeele P. Many stimuli pull the necrotic trigger, an overview. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19(1):75–86. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tenev T, Bianchi K, Darding M, et al. The Ripoptosome, a signaling platform that assembles in response to genotoxic stress and loss of IAPs. Mol Cell. 2011;43(3):432–448. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vandenabeele P, Galluzzi L, Vanden Berghe T, Kroemer G. Molecular mechanisms of necroptosis: an ordered cellular explosion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(10):700–714. doi: 10.1038/nrm2970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun L, Wang H, Wang Z, et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell. 2012;148(1–2):213–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao J, Jitkaew S, Cai Z, et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like is a key receptor interacting protein 3 downstream component of TNF-induced necrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(14):5322–5327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200012109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim YS, Morgan MJ, Choksi S, Liu ZG. TNF-induced activation of the Nox1 NADPH oxidase and its role in the induction of necrotic cell death. Mol Cell. 2007;26(5):675–687. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jørgensen K, Davidson B, Flørenes VA. Activation of c-jun N-terminal kinase is associated with cell proliferation and shorter relapse-free period in superficial spreading malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(11):1446–1455. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuo RC, Lin CY, Kuo MY. Prognostic role of c-Jun activation in patients with areca quid chewing-related oral squamous cell carcinomas in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2006;105(3):229–234. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60310-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colbert LE, Fisher SB, Hardy CW, et al. Pronecrotic mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein expression is a prognostic biomarker in patients with early-stage resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2013;119(17):3148–3155. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pham DL, Scheble V, Bareiss P, et al. SOX2 expression and prognostic significance in ovarian carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2013;32(4):358–367. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e31826a642b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qiu JJ, Guo JJ, Lv TJ, et al. Prognostic value of centromere protein-A expression in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Tumour Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0860-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vakifahmetoglu H, Olsson M, Tamm C, Heidari N, Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B. DNA damage induces two distinct modes of cell death in ovarian carcinomas. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15(3):555–566. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang LJ, Hao YZ, Hu CS, et al. Inhibition of apoptosis facilitates necrosis induced by cisplatin in gastric cancer cells. Anticancer Drugs. 2008;19(2):159–166. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3282f30d05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palmieri C, Gojis O, Rudraraju B, et al. Expression of steroid receptor coactivator 3 in ovarian epithelial cancer is a poor prognostic factor and a marker for platinum resistance. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(10):2039–2044. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Califano D, Pignata S, Losito NS, et al. High HMGA2 expression and high body mass index negatively affect the prognosis of patients with ovarian cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2014;229(1):53–59. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou S, Tang L, Wang H, et al. Overexpression of c-Abl predicts unfa-vorable outcome in epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]