Abstract

Aminoglycoside antibiotics remain the drugs of choice for treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections, particularly for respiratory complications in cystic-fibrosis patients. Previous studies on other bacteria have shown that aminoglycosides have their primary target within the decoding region of 16S rRNA helix 44 with a secondary target in 23S rRNA helix 69. Here, we have mapped P. aeruginosa rRNAs using MALDI mass spectrometry and reverse transcriptase primer extension to identify nucleotide modifications that could influence aminoglycoside interactions. Helices 44 and 45 contain indigenous (housekeeping) modifications at m4Cm1402, m3U1498, m2G1516, m62A1518, and m62A1519; helix 69 is modified at m3Ψ1915, with m5U1939 and m5C1962 modification in adjacent sequences. All modifications were close to stoichiometric, with the exception of m3Ψ1915, where about 80% of rRNA molecules were methylated. The modification status of a virulent clinical strain expressing the acquired methyltransferase RmtD was altered in two important respects: RmtD stoichiometrically modified m7G1405 conferring high resistance to the aminoglycoside tobramycin and, in doing so, impeded one of the methylation reactions at C1402. Mapping the nucleotide methylations in P. aeruginosa rRNAs is an essential step toward understanding the architecture of the aminoglycoside binding sites and the rational design of improved drugs against this bacterial pathogen.

Keywords: pseudomonas, rRNA modifications, methyltransferases, aminoglycosides, RmtD

Introduction

Aminoglycosides are a group of broad-spectrum antibiotics that are widely used against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. The aminoglycoside tobramycin has found extensive application in the treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections, particularly for cystic fibrosis patients where this Gram-negative pathogen is a frequent cause of pulmonary complications.1 Over 60% of cystic fibrosis patients are chronically infected with P. aeruginosa by the age of 20.2 Treatment with tobramycin prolongs life expectancy, although the drug has a mainly palliative role reducing the intensity of infections without measurable success at eradicating them.3 For want of better therapeutics, however, aminoglycosides will undoubtedly retain an important role in the immediate future.4 Treatment is generally via tobramycin inhalation,5 and recent improvements in therapy have been confined to the drug delivery systems. Clearly, more effective aminoglycosides are now required and any rational development of these compounds will require a thorough understanding of the rRNA targets. The rRNAs of P. aeruginosa have previously remained uncharted territory.

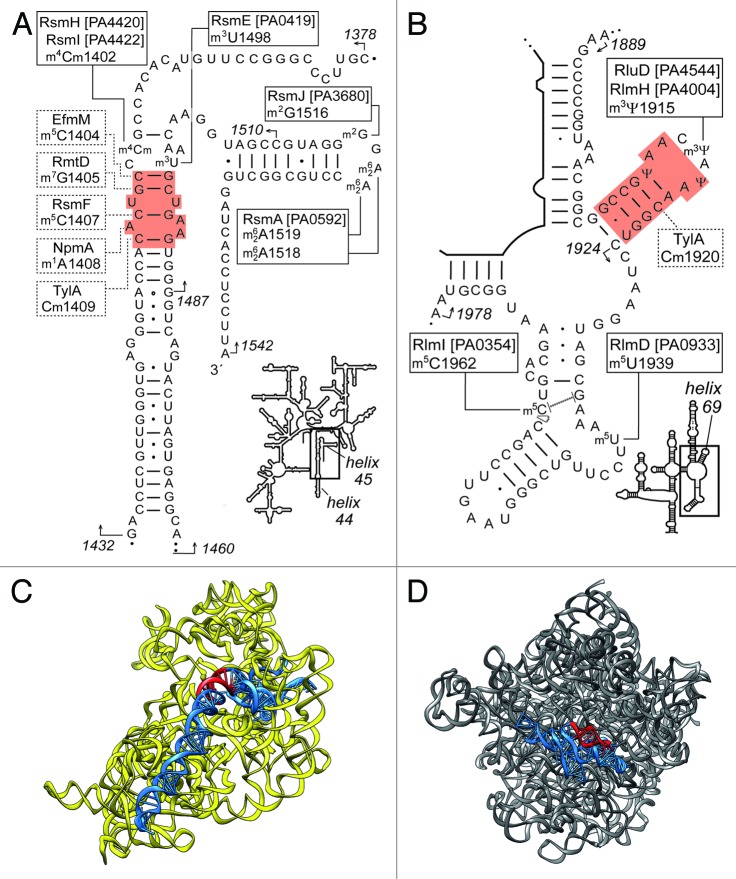

Aminoglycoside antibiotics, including tobramycin, exert their antimicrobial effects by disturbing protein synthesis on the bacterial ribosome.6,7 There are two sites of aminoglycoside interaction on the ribosome, and the primary drug target is at the mRNA decoding region on the 30S ribosomal subunit (Fig. 1A). Here, aminoglycosides interact with highly conserved nucleotides at the ribosomal A site of 16S rRNA helix 44 (H44) where codon–anticodon interactions are monitored.8-12 Drug interaction here causes loss of translational fidelity, the accumulation of erroneous proteins and, ultimately, bacterial death.6,13 Recently, a second aminoglycoside site was discovered within another functionally important region on the 50S ribosomal subunit in helix 69 (H69) of 23S rRNA.14,15 H69 interacts with H44 to form interbridge B2a at the interface of the two subunits.16 Subsequent to termination of mRNA translation,17 ribosome recycling factor binds to this interbridge and, in conjunction with elongation factor G, dissolves the H69-H44 interaction enabling the two ribosomal subunits to separate. Aminoglycoside binding within H69 (Fig. 1B) stabilizes the interbridge contacts and interferes with the subunit recycling process.14,18

Figure 1. Aminoglycoside binding-sites (red) within the rRNAs of P. aeruginosa. (A) Helices 44 and 45 of 16S rRNA showing the indigenous housekeeping methylations mapped in this study at m4Cm1402, m3U1498, m2G1516, m62A1518, and A62A1519, together with the respective enzymes and P. aeruginosa gene loci (unbroken lines and boxes). The acquired methylation catalyzed by RmtD at m7G1405 (dashed lines and boxes) confers tobramycin resistance. Modifications seen in other bacteria (but not in P. aeruginosa) together with the associated methyltransferases include: m5C1404 catalyzed by EfmM33; m5C1407 by RsmF22; m1A1408 by NpmA38; and Cm1409 by TlyA,43 and are also indicated by dashed lines. (B) Modification at m3Ψ1915 within the loop of 23S rRNA helix 69, and in neighboring structures at m5U1939 and m5C1962; P. aeruginosa lacks TlyA and, thus, the second target of this enzyme at C1920 is unmodified. Uridine isomerisation is mass neutral and the Ψ1911 and Ψ1917 modifications remain putative. Start and end points of the oligos used for rRNA isolation and MS analyses are shown by the arrows. (C) Positions of helices 44 and 45 (blue) with the aminoglycoside site highlighted (red) on the 16S rRNA tertiary structure (redrawn from PDB file 3I1M of the E. coli 30S subunit with r-proteins removed). (D) Helix 69 (red) with the surrounding 23S rRNA sequences in blue (redrawn from 3I1P, E. coli 50S subunit with r-proteins removed).

Helices 44 and 69 and adjacent rRNA sequences are targeted by several nucleotide modification enzymes, consistent with the notion that modifications tend to occur in rRNA regions that are of primary functional importance.19,20 The sites of the indigenous (housekeeping) modifications have been comprehensively mapped within Escherichia coli rRNAs, and consist of 11 modified nucleotides in 16S rRNA and 25 in 23S rRNA. Housekeeping modifications are added within H44 by the methyltransferases RsmH and RsmI at nucleotide m4Cm1402,21 by RsmF at m5C1407,22 and by RsmE at m3U1498.23 Within the loop of the adjacent 16S rRNA helix H45, m2G1516 is modified by RsmJ,24 and m62A1518 and m62A1519 by RsmA.25,26 At the second aminoglycoside side in H69 of 23S rRNA, three uridine isomerizations are introduced in the loop by the enzyme RluD to form Ψ1911, Ψ1915, and Ψ191719 and Ψ1915 is then methylated at the N3-position by RlmH.27,28 Other methylations in the same region at nucleotides m5U1939 and m5C1962 are catalyzed by RlmD29,30 and by RlmI,31 respectively. Orthologs of some of the genes encoding these modification enzymes are evident in other Gram-negative bacteria.32

In addition to the enzymes that add the rRNA housekeeping modifications, several other methyltransferases modify 16S rRNA H44, and in doing so confer resistance to aminoglycosides. Such is the case with methylation at m5C1404,33 m7G1405, and m1A1408 (Fig. 1A). Methyltransferases directing the latter two modifications are more prevalent in clinical pathogens and show similarity to enzymes originally identified in aminoglycoside-producing actinomycetes.34,35 The m7G1405 methyltransferases include ArmA and RmtA-RmtH,36-39 and confer high-level resistance to 4,6-disubstituted 2-deoxystreptamines (2-DOS) aminoglycosides, including tobramycin; the m1A1408 methyltransferases include NpmA, and these enzymes confer resistance to both 4,5-disubstituted 2-DOS and 4,6-disubstituted 2-DOS aminoglycosides.40

Recently, the rmtD methyltransferase gene was shown to be prevalent in clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa that are highly resistance to tobramycin.41 Here, we map the housekeeping modifications within the aminoglycoside binding sites of 16S and 23S rRNAs from the aminoglycoside-sensitive P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 and a resistant clinical strain containing rmtD. We address the questions as to whether any of the housekeeping modifications could affect drug binding at either of the aminoglycoside sites, and whether the acquisition of RmtD activity hindered any of the indigenous methyltransferases in gaining access to their nucleotide targets.

Results and Discussion

Modifications at 16S rRNA nucleotides m4Cm1402, m3U1498, m2G1516, m62A1518, and m62A1519

The P. aeruginosa PAO1 genome contains genes for several enzymes that share significant similarity with characterized E. coli rRNA methyltransferases (Table 1). To ascertain whether the PAO1 orthologs are expressed and do in fact modify the main aminoglycoside binding site at the decoding region of 16S rRNA, this region was analyzed using MALDI-MS and reverse transcriptase primer extension.

Table 1. Modified nucleotides within the aminoglycoside binding sites of 16S and 23S rRNAs.

| |

rRNA modification |

E. coli genes encodingmodifying enzymes |

Reference for E. coli |

Putative PAO1 genes encoding modifyin enzymes |

% ID PAO1 |

% G+C content of gene orthologs |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Name |

Synonym(s) |

Name |

E. coli |

PAO1 |

||||

| 16S rRNA | ||||||||

| 1402 |

m4C |

rsmH |

mraW |

21 |

PA4420 |

53.3 |

55.6 |

64.4 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1402 |

Cm |

rsmI |

yraL |

21 |

PA4422 |

58.3 |

54.6 |

67.4 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1407 |

m5C |

rsmF |

yebU |

22 |

no |

no |

51.8 |

no |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1498 |

m3U |

rsmE |

yggJ |

23 |

PA0419 |

46.1 |

53.0 |

71.2 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1516 |

m2G |

rsmJ |

yhiQ |

24 |

PA3680 |

43.3 |

58.2 |

71.4 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1518, 1519 |

m62A |

rsmA |

ksgA |

25, 26 |

PA0592 |

48.3 |

53.0 |

66.0 |

| 23S rRNA | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1911, 1915, 1917 |

Ψ |

rluD |

yfiI |

19 |

PA4544 |

54.6 |

52.8 |

66.9 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1915 |

m3Ψ |

rlmH |

ybeA |

27, 28 |

PA4004 |

53.8 |

58.5 |

68.6 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1939 |

m5U |

rlmD |

ygcA, rumA |

29, 30 |

PA0933 |

36.5 |

51.5 |

67.1 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1962 | m5C | rlmI | yccW | 31 | PA0354 | 33.5 | 51.8 | 67.4 |

Putative methyltransferases were identified in silico in the genome of P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 by their similarity to the E. coli enzymes (gene annotations shown here).The percentages of identical amino acids in the encoded enzymes are indicated (% ID PAO1). The G–C base-pair content is given for each gene (% G+C), and can be compared with the overall G–C content within the E. coli genome (50.8%) and the P. aeruginosa PAO1 genome (66.6%). no, no orthologous gene.

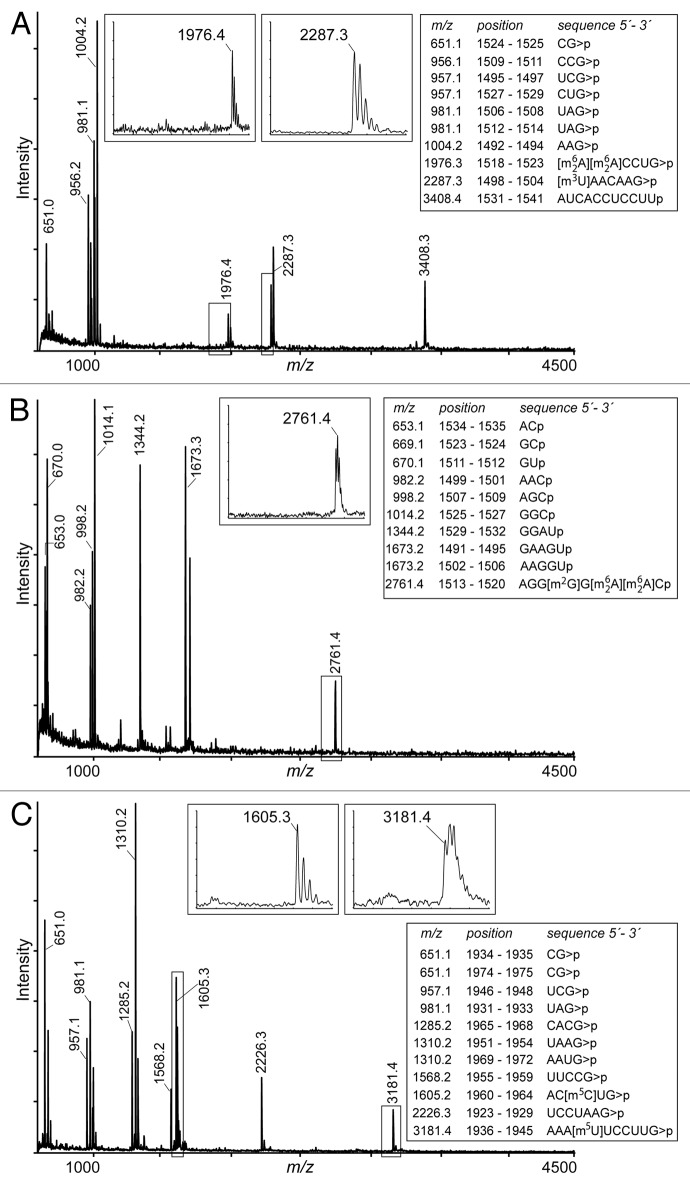

The sequences 1460–1510 and 1487–1542, which make up H45 and the 3′-portion of the decoding site in H44, were shown to contain several methylated nucleotides. The MS spectra clearly showed the presence of m62A1518 and m62A1519 in the RNase T1 fragment [m62A][m62A]CCUG (A1518-G1523) at m/z 1976 (Fig. 2A), as well as in the RNase A fragment AGG[m2G]G[m62A][m62A]C (A1513-C1520) at m/z 2761 (Fig. 2B). There was no evidence of peaks with masses that were smaller by multiples of 14 Da (indicating a proton rather than a methyl group), and it was concluded from this that both A1518 and A1519 were completely (stoichiometrically) dimethylated. These modifications are added in E. coli by RsmA (KsgA)25,26 at a late assembly stage of the 30S ribosomal subunit,42 and are presumably mediated in the same manner by the homologous P. aeruginosa enzyme encoded by the PA0592 gene (Table 1). The m/z 2761 peak also contained stoichiometric amounts of a fifth methyl group that was mapped to nucleotide G1516. Modification at m2G1516 is catalyzed on the E. coli 30S subunit by RsmJ,24 and the homologous enzyme is presumably encoded by PA3680 in P. aeruginosa.

Figure 2. MALDI-MS analyses of the aminoglycoside sites within P. aeruginosa rRNAs. (A) RNase T1 digestion products of the 16S rRNA sequence G1487 to A1542 reveals the dimethylated adenosines m62A1518 and m62A1519 in the m/z 1976 peak. The lack of significant peaks smaller by multiples of 14 Da (box) indicates that addition of these four methyl groups by RsmA is essentially stoichiometric. The m3U1498 modification is seen in the m/z 2287 peak, and is also stoichiometric. Masses are shown for the 2´-3′-cyclic phosphate fragments (> P) with the exception of the 3′-fragment (m/z 3408) where the ultimate adenosine A1542 was missing. (B) RNase A analysis of the same sequence. The two adenosines m62A1518 and m62A1519 are in the m/z 2761 peak with m2G1516; all five methylations are stoichiometric (box). Masses are with a linear (hydrated) 3′-phosphate (p). (C) RNase T1 digestion products of the 23S rRNA sequence C1924 to G1978. Nucleotide m5C1962 migrates in the fragment at m/z 1605, and m5U1939 at m/z 3181. Enlargements of these regions (boxes) show that methylation reactions by RlmI and RlmD, respectively, are close to complete. Spectra from these rRNA regions of P.aeruginosa strains BB1285 and PAO1 (with and without RmtD) were indistinguishable. The theoretical (boxed) and empirical masses (on peaks) matched to within 0.2 Da.

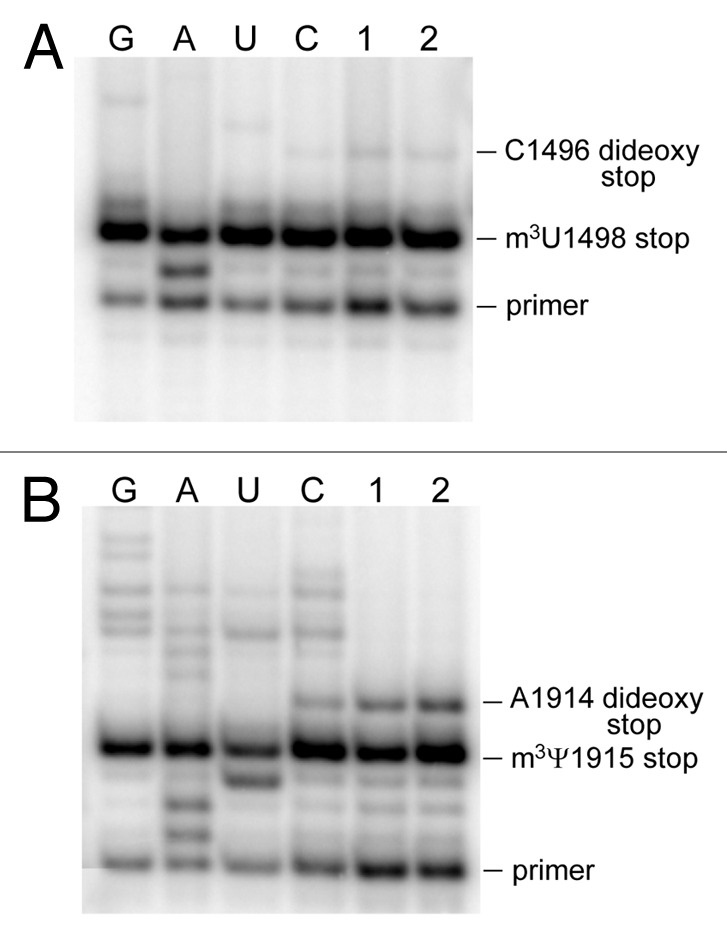

Screening the sequence between H44 and H45 by primer extension produced an intense stop band indicating the presence of a modification on nucleotide U1498 (Fig. 3A). Methylation at the 5-position of the uracil or 2´-O of the ribose could be excluded, as these would have respectively resulted in either no stop or merely a partial pausing of reverse transcription,43 so it was concluded that this modification was m3U1498. The level of m3U modification was quantified as being > 97% (Fig. 3A). The primer extension data was fully consistent with the MS analyses where the U1498-G1504 sequence flew exclusively at m/z 2287, corresponding to [m3U]AACAAG, with no evidence of an unmethylated fragment at m/z 2273 (Fig. 2A). The m3U1498 modification is added by RsmE in E. coli23 and requires a fully assembled 30S subunit as a substrate for methylation.44 The equivalent methyltransferase would be encoded by PA0419 in P. aeruginosa.

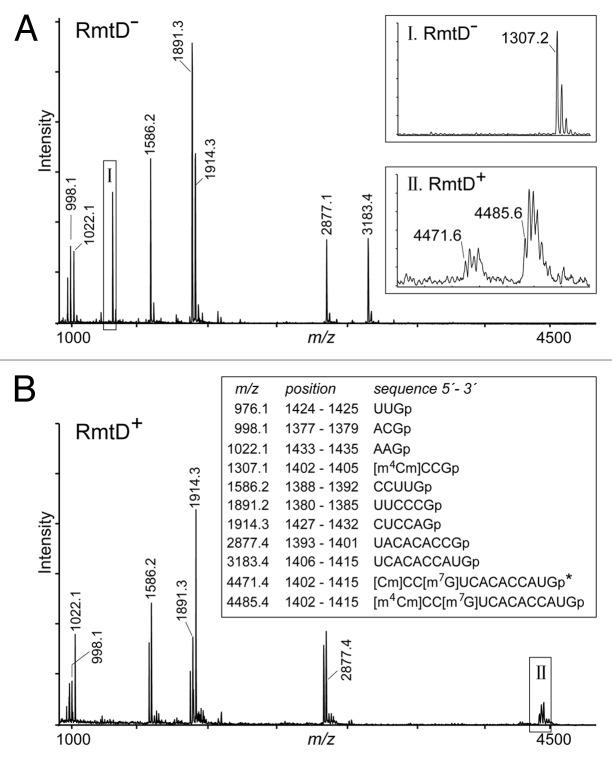

Figure 3. Gel autoradiograms of primer extension on P. aeruginosa rRNAs. (A) 16S rRNA showing the strong stop directly before the m3U1498 modification, and (B) on 23S rRNA with the stop before m3Ψ1915. Lanes 1 and 2 are from P. aeruginosa strains BB1285 and PAO1, respectively. Read-through at the modification sites was terminated by ddGTP or ddTTP (dideoxy stop) and the intensities of these bands reflect the amounts of unmethylated U1498 and Ψ1915. The dideoxy sequencing reactions C, U, A, and G were performed on PAO1 rRNA.

In the 1378–1432 region, two modifications were observed at nucleotide C1402 and these were shown to be equivalent to those added by the E. coli N4-methyltransferase RsmH and the 2´-O-methyltransferase RsmI.21 The peak from the P. aeruginosa rRNA at m/z 1307 corresponds to the fragment [m4Cm]CCG (C1402-G1405), and both methylations appear to be stoichiometric, with no peaks at m/z 1279 or m/z 1293 (Fig. 4A). The genes encoding the P. aeruginosa RsmH/RsmI methyltransferases in are listed in Table 1. No other modifications were evident in the H44 and H45 regions of the P. aeruginosa 16S rRNA.

Figure 4. MALDI-MS spectra of RNase T1 fragments from the 16S rRNA sequence C1378-G1432 derived from aminoglycoside-susceptible and -resistance P. aeruginosa strains. (A) In the RmtD-strain PAO1, G1405 is unmodified and migrates in the m/z 1307 fragment; nucleotide C1407 is in the RNase T1 fragment at m/z 3183 and contains no modification. (B) In the resistant RmtD+ strain BB1285, these two fragments are completely absent, and a new peak appears at m/z 4485, indicating stoichiometric methylation at m7G1405. The minor peak at m/z 4471 (box II) arises from partial loss of one of the C1402 methylations, both of which were stoichiometric prior to RmtD expression (box I). There was insufficient fragment material to determine whether RmtD interferes with the 2´-O- or N4-methylation at C1402 (*). The multiple tops in the enlargement (boxes) reflect the natural distribution of 12C and 13C isotopes; the 12C monoisotopic masses of products with linear 3′-phosphates are given here; in spectrum B, smaller amounts of 2´-3′-cyclic products are evident to the left of each main peak.

P. aeruginosa lacks a homolog of RsmF that modifies m5C1407 in E. coli 16S rRNA

The P. aeruginosa fragment UCACACCAUG (U1406-G1415) contains no modification, and flew at m/z 3183 (Fig. 4). Thus, the m5C1407 modification added in E. coli rRNA by the housekeeping methyltransferase RsmF22 is absent in P. aeruginosa. Consistent with this, no rsmF homolog could be identified in the P. aeruginosa PAO1 genome (Table 1). This gene is conserved in the Enterobacteriaceae including Salmonella, Klebsiella, and Shigella homologs with > 80% amino acid identity; other Orders, including Aeromonadales, Alteromonadales, and Vibrionales, contain ORFs that are around 58% identical to RsmF. A dendrogram for genetic similarity in Gammaproteobacteria shows that those bacteria lacking RsmF are genetically related, while the bacteria possessing RsmF also cluster together. Thus, RsmF seems to have an early origin during speciation of Gram-negative bacteria in prokaryotes, and has been lost in P. aeruginosa most likely through a single deletion event in a common ancestor (Fig. S1). Also absent in P. aeruginosa is the 2'-O-methyltransferase TlyA, which modifies nucleotide C1409 in 16S rRNA and C1920 in 23S rRNA (Fig. 1) and is linked with capreomycin resistance in mycobacteria.45

Modifications at 23S rRNA nucleotides m3Ψ1915, m5U1939, and m5C1962

Screening the P. aeruginosa genome in silico revealed several candidates for genes encoding enzymes that might modify the secondary aminoglycoside binding site within H69 of 23S rRNA. These included the gene encoding the pseudouridine synthase RluD, which isomerizes the 23S rRNA nucleotides U1911, U1915 and U1917 in the E. coli helix 69 loop.17,46 Nucleotide Ψ1915 is subsequently methylated by RlmH to form m3Ψ1915,27,28 and RlmH activity has been shown to be dependent on prior RluD-catalyzed isomerization of this nucleotide.28 Species analyzed thus far have been shown to possess an RlmH ortholog only when accompanied by an RluD ortholog. P. aeruginosa is no exception, and possesses both of these enzymes, respectively, encoded by PA4004 and PA4544. Methylation of the P. aeruginosa rRNA was indicated by the strong primer extension stop before Ψ1915 (Fig. 3B), consistent with the RlmH-directed m3Ψ modification. The level of methylation at this nucleotide (no more than 80% of rRNA molecules) appears to reflect a mode of substrate recognition similar to that seen in E. coli, where RluD methylates Ψ1915 only after association of the newly assembled 50S subunit into the 70S ribosome complex.28

Putative gene homologs encoding the methyltransferases RlmD and RlmI were also evident in P. aeruginosa, which in E. coli are responsible for methylation at m5U193929 and m5C1962,31 respectively. MALDI-MS spectra of RNase T1 digestion products showed that a methyl group was present on C1962 in the fragment AC[m5C]UG (A1960-G1964) at m/z 1605 and on U1939 in the fragment AAA[m5U]UCCUUG (A1936-G1845) at m/z 3181 (Fig. 2C). Enlargements of these spectral regions show only trace amounts of products with 14 Da lower mass (m/z 1591 and 3167), indicating that methylation at these targets is almost complete. No other modifications were evident in this region of the P. aeruginosa 23S rRNA. The predictions of modification enzymes made in silico matched the empirical data—all the rRNA modifications predicted by the search were shown to occur and, conversely, there were no modifications at sites where enzymes were predicted to be absent (Table 1).

Acquisition of the RmtD methyltransferase confers high-level resistance to aminoglycosides

The minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of aminoglycoside drugs required to stop growth of P. aeruginosa BB1285 are considerably higher than for the susceptible strain PAO1 (Table 2). Expression of rmtD in BB1285 facilitates growth of this pathogenic strain at a tobramycin concentration that is over 200-fold higher than required to inhibit cells lacking this methyltransferase gene.

Table 2. Susceptibilities to aminoglycosides of the P. aeruginosa strains PAO1 and BB1285 rmtD+.

| |

P. aeruginosa PAO1 |

P. aeruginosa BB1285 (rmtD+) |

|---|---|---|

| Aminoglycoside | MIC (μg/mL) | |

| Gentamicin |

2 |

> 512 |

| Kanamycin |

128 |

> 512 |

| Tobramycin |

0.5 |

128 |

| Amikacin |

2 |

> 512 |

| Arbekacin |

4 |

> 512 |

| Neomycin |

8 |

32 |

| Apramycin | 8 | 8 |

The relatively high tolerance of the PAO1 strain to kanamycin is due to a mechanism unrelated to rRNA modification. Here, a chromosome-coded N3-acetyltransferase50 confers resistance to a subset of aminoglycosides.

The P. aeruginosa BB1285 rRNAs were analyzed to define the methylation site of RmtD, and to see whether acquisition of this resistance determinant influenced the functioning of any of the housekeeping methyltransferases at adjacent sites. MALDI-MS analysis of 16S rRNA from the BB1285 strain revealed the loss of the two fragments [m4Cm]CCG and UCACACCAUG, seen for the susceptible strain at m/z 1307 and m/z 3183, respectively, with the concomitant appearance of a new fragment [m4Cm]CC[m7G]UCACACCAUG (C1402-G1415) at m/z 4485 (Fig. 4B). This fragment arises because hydrolysis by RNase T1 at G1405 is prevented by the N7-methylation. The sequence and base position of this methylation were confirmed by primer extension (Fig. S2). The catalysis of m7G1405 modification by RmtD and the subsequent high-level resistance to the subset of 4,6-disubstituted 2-deoxystreptamines aminoglycosides (Table 2) fit well with the function of other Arm/Rmt methyltransferase orthologs characterized to date.47

Interference between acquired and indigenous methyltransferases

Closer scrutiny of the spectral region around m/z 4485 in the BB1285 strain reveals a second peak at m/z 4471, corresponding to a proportion of 16S rRNA molecules with two (rather than three) methyl groups in the C1402-G1415 sequence. Obviously the m7G1405 methylation is still present, otherwise the sequence would have been cleaved to lower masses and, therefore, the methyl group at the 2´-O- or the N4-position of C1402 must be missing. In the PAO1 strain where there is no m7G1405 methylation, nucleotide C1402 is present in the fragment at m/z 1307, and the lack of any smaller peaks in this spectral region (Fig. 4A) shows that both the 2´-O- and N4-methylations are added stoichiometrically. Incomplete methylation at C1402 in the BB1285 strain indicates that RmtD is impeding one of the C1402 methylation reactions.

Other recent studies have shown a reduction in modification by the E. coli enzyme RsmF at 16S rRNA m5C1407 in the presence of Sgm48 or Arm/Rmt methyltransferases,49 all of which methylate the 7-position of G1405. Despite this interference with the function of a housekeeping methyltransferase, expression of the chromosome-coded arm/rmt genes did not entail any detectable fitness cost, measured in terms of growth rate and competition under laboratory conditions.49 The RsmI and RsmH enzymes responsible for the 2´-O- and N4-methylations of C1402 are present in all bacterial species and are thus more highly conserved than RsmF. Interference with modification at C1402 might therefore be expected to have a more distinct (but as yet undefined) biological cost.

Common for all these housekeeping enzymes that methylate the decoding region (Table 1), as well as for those associated with resistance such as Armt/Rmt47 and TlyA,50 is that they all require a 16S rRNA substrate that has been assembled with its r-proteins. The reactions performed by these methyltransferases coincide within a time-frame subsequent to 30S subunit assembly, but prior to its association with the 50S. Considering the sizes of the methyltransferases and the spatial proximity of their targets, it is perhaps not surprising that steric hindrance occurs when an extra enzyme such as RmtD is introduced. The fact that modifications by the indigenous rRNA methyltransferase are for the most part stoichiometric reflects how these enzymes have evolved in conjunction with the ribosomal components such that they function effectively in a highly orchestrated manner.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and isolation of rRNA

The strains used in this study were the wild-type P. aeruginosa PAO1 and P. aeruginosa strain BB1285, an aminoglycoside-resistant clinical isolate from Brazil harbouring rmtD and bla (SPM-1). The strains were cultured at 37 °C in 200 ml Luria-Bertani broth (Difco) containing kanamycin at 50 μg/ml where appropriate. Cells were grown to mid-log phase, harvested by centrifugation, washed twice with 50 mM TRIS-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NH4Cl at 4 °C, and then lyzed by sonication in the same buffer. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation, the supernatant was extracted with phenol and chloroform to remove proteins, and the total cellular RNA was recovered by ethanol precipitation.

Bioinformatic analyses

BLAST searches51 were restricted to the P. aeruginosa PAO1 genome52 using the sequences of modification enzymes from E. coli strain K-12 sub-strain W3110 (GenBank accession number NC_007779) as queries. These E. coli enzymes were previously characterized as being responsible for methylation and uridine isomerization adjacent to the aminoglycoside binding sites, and include RsmA, RsmE, RsmF, RsmH, RsmI, and RsmJ modifying E. coli 16S rRNA, and RlmD, RlmH, RlmI, and RluD that are specific for 23S rRNA (Table 1).

MALDI mass spectrometry analysis

Specific sequences of approximately 50 nucleotides were isolated from the 16S and 23S rRNAs of P. aeruginosa strains PAO1 and BB1285. Five complementary deoxyoligonucleotides were hybridized to the P. aeruginosa 16S rRNA sequences C1378 to G1432, C1460 to C1510, and G1487 to A1542 and the 23S rRNA sequence C1924 to G1978 and A1889 to G1948 (strain PAO1 GenBank accession number AE004091); the E. coli numbering system is used throughout (Fig. 1). 100 pmol of rRNA was heated with 500 pmol of deoxyoligonucleotide at 80 °C for 5 min and cooled to 35 °C over 2 h. Regions of the rRNAs that were not protected by hybridization were removed by digestion with 20 U of mung bean nuclease (NE Biolabs) and 0.25 μg of RNase A (Sigma-Aldrich), and the protected rRNA sequences were separated by gel electrophoresis.43,53 Each isolated rRNA sequence was digested overnight with 3 U of RNase T1 (Roche Diagnostics) or 0.25 μg of RNase A (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37 °C in 3μl aqueous solution of 60 mM 3-hydroxypicolinic acid. Samples were analyzed by Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS, Voyager Elite, Perseptive Biosystems) recording in reflector and positive ion mode.54 Spectra were interpreted with the program m/z (Proteometrics Inc.).

Primer extension analysis

Several rRNA modifications, including m3U and m3Ψ, can be detected by their ability to impede reverse transcription. Primers complementary to 16S rRNA nucleotides 1501–1517 and 23S rRNA nucleotides 1920–1939 were used to evaluate the modifications at m3U1498 and m3Ψ1915, respectively. Extensions were performed with 1 mM dTTP, dATP, dCTP, and 5 mM ddGTP; the reactions stop immediately before m3U or m3Ψ, or run through on unmethylated rRNA templates to be terminated by ddG at the next cytosine in the sequence. Primer 1459–1479 was used for detection of methylation at the N7-position of G1405 (m7G1405) after reduction of the rRNAs with sodium borohydride (NaBH4), followed by cleavage with aniline.55 The cleavage reaction is generally incomplete56 and was improved by including hypermethylated tRNA carrier in the reactions.57 Each deoxynucleotide primer was 5′-end labeled with 32P, and 3 pmol was extended on 2 μg of rRNA with 1.5 U of AMV reverse transcriptase (Finnzymes).58 Extensions products were run on denaturing polyacrylamide/urea gels alongside dideoxy sequencing reactions performed on P. aeruginosa PAO1 rRNAs. Gel bands were visualized and quantified by phosphorimaging (Typhoon, Amersham Biosciences), and the stoichiometry of m3U and m3Ψ modifications was calculated from the ratio of the methylated:didedoxy bands.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

P. aeruginosa strains were studied using in-house microtiter plates according to the CLSI guidelines59 to evaluate their susceptibility to the 4,6-disubstituted 2-DOS aminoglycosides, gentamicin, kanamycin, tobramycin, amikacin, and arbekacin, and also to the 4,5-disubstituted 2-DOS, neomycin, and the 4-substituted 2-DOS, apramycin (Table 2).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Natalia Montero, Simon Rose, and Lykke Haastrup Hansen are thanked for excellent technical assistance. We acknowledge the Universidad Complutense de Madrid for the PhD scholarship of BG. This work was supported by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (BIO 2010-20204 and PRI-PIBIN-2011-0915), the EU FP7 Health Project EvoTAR, and Marie-Curie Action ITN Train-Asap FP7/2007-2013 (nº289285). SD gratefully acknowledges support from the Danish Research Agency (FNU-rammebevillinger 09-064292/10-084554).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- MALDI-MS

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry

- rRNA

ribosomal RNA

- H44

helix 44

- H69

helix 69

- H45

helix 45

- 2-DOS

2- deoxystreptamines

- MIC

minimal inhibitory concentration

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/rnabiology/article/25984

References

- 1.Pier GB, Grout M, Zaidi TS, Olsen JC, Johnson LG, Yankaskas JR, Goldberg JB. Role of mutant CFTR in hypersusceptibility of cystic fibrosis patients to lung infections. Science. 1996;271:64–7. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5245.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folkesson A, Jelsbak L, Yang L, Johansen HK, Ciofu O, Høiby N, Molin S. Adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the cystic fibrosis airway: an evolutionary perspective. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:841–51. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith EE, Buckley DG, Wu Z, Saenphimmachak C, Hoffman LR, D’Argenio DA, Miller SI, Ramsey BW, Speert DP, Moskowitz SM, et al. Genetic adaptation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8487–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602138103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geller DE, Pitlick WH, Nardella PA, Tracewell WG, Ramsey BW. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of aerosolized tobramycin in cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2002;122:219–26. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibson RL, Emerson J, McNamara S, Burns JL, Rosenfeld M, Yunker A, Hamblett N, Accurso F, Dovey M, Hiatt P, et al. Cystic Fibrosis Therapeutics Development Network Study Group Significant microbiological effect of inhaled tobramycin in young children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:841–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200208-855OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogle JM, Ramakrishnan V. Structural insights into translational fidelity. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:129–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.061903.155440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies J, Davis BD. Misreading of ribonucleic acid code words induced by aminoglycoside antibiotics. The effect of drug concentration. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:3312–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter AP, Clemons WM, Brodersen DE, Morgan-Warren RJ, Wimberly BT, Ramakrishnan V. Functional insights from the structure of the 30S ribosomal subunit and its interactions with antibiotics. Nature. 2000;407:340–8. doi: 10.1038/35030019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fourmy D, Recht MI, Blanchard SC, Puglisi JD. Structure of the A site of Escherichia coli 16S ribosomal RNA complexed with an aminoglycoside antibiotic. Science. 1996;274:1367–71. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moazed D, Noller HF. Interaction of antibiotics with functional sites in 16S ribosomal RNA. Nature. 1987;327:389–94. doi: 10.1038/327389a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Purohit P, Stern S. Interactions of a small RNA with antibiotic and RNA ligands of the 30S subunit. Nature. 1994;370:659–62. doi: 10.1038/370659a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vicens Q, Westhof E. Crystal structure of a complex between the aminoglycoside tobramycin and an oligonucleotide containing the ribosomal decoding a site. Chem Biol. 2002;9:747–55. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(02)00153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shandrick S, Zhao Q, Han Q, Ayida BK, Takahashi M, Winters GC, Simonsen KB, Vourloumis D, Hermann T. Monitoring molecular recognition of the ribosomal decoding site. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2004;43:3177–82. doi: 10.1002/anie.200454217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borovinskaya MA, Pai RD, Zhang W, Schuwirth BS, Holton JM, Hirokawa G, Kaji H, Kaji A, Cate JH. Structural basis for aminoglycoside inhibition of bacterial ribosome recycling. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:727–32. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L, Pulk A, Wasserman MR, Feldman MB, Altman RB, Cate JHD, Blanchard SC. Allosteric control of the ribosome by small-molecule antibiotics. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:957–63. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cate JH, Yusupov MM, Yusupova GZ, Earnest TN, Noller HF. X-ray crystal structures of 70S ribosome functional complexes. Science. 1999;285:2095–104. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5436.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Connor M, Gregory ST. Inactivation of the RluD pseudouridine synthase has minimal effects on growth and ribosome function in wild-type Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:154–62. doi: 10.1128/JB.00970-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheunemann AE, Graham WD, Vendeix FA, Agris PF. Binding of aminoglycoside antibiotics to helix 69 of 23S rRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:3094–105. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ofengand J, Del Campo M. Modified nucleosides in Escherichia coli ribosomal RNA. In: Curtiss R, ed. EcoSal-Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. Washington, DC: ASM, 2004; chapter 4.6.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Decatur WA, Fournier MJ. rRNA modifications and ribosome function. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:344–51. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(02)02109-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimura S, Suzuki T. Fine-tuning of the ribosomal decoding center by conserved methyl-modifications in the Escherichia coli 16S rRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:1341–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersen NM, Douthwaite S. YebU is a m5C methyltransferase specific for 16 S rRNA nucleotide 1407. J Mol Biol. 2006;359:777–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basturea GN, Rudd KE, Deutscher MP. Identification and characterization of RsmE, the founding member of a new RNA base methyltransferase family. RNA. 2006;12:426–34. doi: 10.1261/rna.2283106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basturea GN, Dague DR, Deutscher MP, Rudd KE. YhiQ is RsmJ, the methyltransferase responsible for methylation of G1516 in 16S rRNA of E. coli. J Mol Biol. 2012;415:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helser TL, Davies JE, Dahlberg JE. Mechanism of kasugamycin resistance in Escherichia coli. Nat New Biol. 1972;235:6–9. doi: 10.1038/newbio235006a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poldermans B, Roza L, Van Knippenberg PH. Studies on the function of two adjacent N6,N6-dimethyladenosines near the 3′ end of 16 S ribosomal RNA of Escherichia coli. III. Purification and properties of the methylating enzyme and methylase-30 S interactions. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:9094–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Purta E, Kaminska KH, Kasprzak JM, Bujnicki JM, Douthwaite S. YbeA is the m3Ψ methyltransferase RlmH that targets nucleotide 1915 in 23S rRNA. RNA. 2008;14:2234–44. doi: 10.1261/rna.1198108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ero R, Peil L, Liiv A, Remme J. Identification of pseudouridine methyltransferase in Escherichia coli. RNA. 2008;14:2223–33. doi: 10.1261/rna.1186608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agarwalla S, Kealey JT, Santi DV, Stroud RM. Characterization of the 23 S ribosomal RNA m5U1939 methyltransferase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8835–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111825200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madsen CT, Mengel-Jørgensen J, Kirpekar F, Douthwaite S. Identifying the methyltransferases for m(5)U747 and m(5)U1939 in 23S rRNA using MALDI mass spectrometry. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:4738–46. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Purta E, O’Connor M, Bujnicki JM, Douthwaite S. YccW is the m5C methyltransferase specific for 23S rRNA nucleotide 1962. J Mol Biol. 2008;383:641–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Machnicka MA, Milanowska K, Osman Oglou O, Purta E, Kurkowska M, Olchowik A, Januszewski W, Kalinowski S, Dunin-Horkawicz S, Rother KM, et al. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways--2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D262–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galimand M, Schmitt E, Panvert M, Desmolaize B, Douthwaite S, Mechulam Y, Courvalin P. Intrinsic resistance to aminoglycosides in Enterococcus faecium is conferred by the 16S rRNA m5C1404-specific methyltransferase EfmM. RNA. 2011;17:251–62. doi: 10.1261/rna.2233511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Conn GL, Savic M, Macmaster R. DNA and RNA Modification Enzymes: Structure, mechanism, function and evolution. In: Grosjean H, ed. DNA and RNA Modification Enzymes: Structure, mechanism, function and evolution. Austin, Texas.: Landes BioScience., 2009; pp. 525-36. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cundliffe E. How antibiotic-producing organisms avoid suicide. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1989;43:207–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.43.100189.001231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wachino J, Arakawa Y. Exogenously acquired 16S rRNA methyltransferases found in aminoglycoside-resistant pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria: an update. Drug Resist Update: 2012 Elsevier Ltd, 2012; 15:133-48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Hidalgo L, Hopkins KL, Gutierrez B, Ovejero CM, Shukla S, Douthwaite S, Prasad KN, Woodford N, Gonzalez-Zorn B. Association of the novel aminoglycoside resistance determinant RmtF with NDM carbapenemase in Enterobacteriaceae isolated in India and the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:1543–50. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bueno MF, Francisco GR, O’Hara JA, de Oliveira Garcia D, Doi Y. Coproduction of 16S rRNA methyltransferase RmtD or RmtG with KPC-2 and CTX-M group extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:2397–400. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02108-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Hara JA, McGann P, Snesrud EC, Clifford RJ, Waterman PE, Lesho EP, Doi Y. Novel 16S rRNA methyltransferase RmtH produced by Klebsiella pneumoniae associated with war-related trauma. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:2413–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00266-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wachino J, Shibayama K, Kurokawa H, Kimura K, Yamane K, Suzuki S, Shibata N, Ike Y, Arakawa Y. Novel plasmid-mediated 16S rRNA m1A1408 methyltransferase, NpmA, found in a clinically isolated Escherichia coli strain resistant to structurally diverse aminoglycosides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:4401–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00926-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doi Y, Ghilardi AC, Adams J, de Oliveira Garcia D, Paterson DL. High prevalence of metallo-beta-lactamase and 16S rRNA methylase coproduction among imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates in Brazil. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3388–90. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00443-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Farrell HC, Pulicherla N, Desai PM, Rife JP. Recognition of a complex substrate by the KsgA/Dim1 family of enzymes has been conserved throughout evolution. RNA. 2006;12:725–33. doi: 10.1261/rna.2310406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Douthwaite S, Kirpekar F. Identifying modifications in RNA by MALDI mass spectrometry. Methods Enzymol. 2007;425:3–20. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)25001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang H, Wan H, Gao ZQ, Wei Y, Wang WJ, Liu GF, Shtykova EV, Xu JH, Dong YH. Insights into the catalytic mechanism of 16S rRNA methyltransferase RsmE (m³U1498) from crystal and solution structures. J Mol Biol. 2012;423:576–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johansen SK, Maus CE, Plikaytis BB, Douthwaite S. Capreomycin binds across the ribosomal subunit interface using tlyA-encoded 2′-O-methylations in 16S and 23S rRNAs. Mol Cell. 2006;23:173–82. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raychaudhuri S, Conrad J, Hall BG, Ofengand J. A pseudouridine synthase required for the formation of two universally conserved pseudouridines in ribosomal RNA is essential for normal growth of Escherichia coli. RNA. 1998;4:1407–17. doi: 10.1017/S1355838298981146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liou GF, Yoshizawa S, Courvalin P, Galimand M. Aminoglycoside resistance by ArmA-mediated ribosomal 16S methylation in human bacterial pathogens. J Mol Biol. 2006;359:358–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cubrilo S, Babić F, Douthwaite S, Maravić Vlahovicek G. The aminoglycoside resistance methyltransferase Sgm impedes RsmF methylation at an adjacent rRNA nucleotide in the ribosomal A site. RNA. 2009;15:1492–7. doi: 10.1261/rna.1618809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gutierrez B, Escudero JA, San Millan A, Hidalgo L, Carrilero L, Ovejero CM, Santos-Lopez A, Thomas-Lopez D, Gonzalez-Zorn B. Fitness cost and interference of Arm/Rmt aminoglycoside resistance with the RsmF housekeeping methyltransferases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:2335–41. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06066-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monshupanee T, Johansen SK, Dahlberg AE, Douthwaite S. Capreomycin susceptibility is increased by TlyA-directed 2′-O-methylation on both ribosomal subunits. Mol Microbiol. 2012;85:1194–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08168.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stover CK, Pham XQ, Erwin AL, Mizoguchi SD, Warrener P, Hickey MJ, Brinkman FS, Hufnagle WO, Kowalik DJ, Lagrou M, et al. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature. 2000;406:959–64. doi: 10.1038/35023079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Andersen TE, Porse BT, Kirpekar F. A novel partial modification at C2501 in Escherichia coli 23S ribosomal RNA. RNA. 2004;10:907–13. doi: 10.1261/rna.5259404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kirpekar F, Douthwaite S, Roepstorff P. Mapping posttranscriptional modifications in 5S ribosomal RNA by MALDI mass spectrometry. RNA. 2000;6:296–306. doi: 10.1017/S1355838200992148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peattie DA. Direct chemical method for sequencing RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:1760–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Douthwaite S, Garrett RA, Wagner R. Comparison of Escherichia coli tRNAPhe in the free state, in the ternary complex and in the ribosomal A and P sites by chemical probing. Eur J Biochem. 1983;131:261–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zueva VS, Mankin AS, Bogdanov AA, Baratova LA. Specific fragmentation of tRNA and rRNA at a 7-methylguanine residue in the presence of methylated carrier RNA. Eur J Biochem. 1985;146:679–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb08704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stern S, Moazed D, Noller HF. Structural analysis of RNA using chemical and enzymatic probing monitored by primer extension. Methods Enzymol. 1988;164:481–9. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(88)64064-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 19th ed. CLSI: PA Wayne, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.