Abstract

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a promising cell source for regenerative medicine; however, their cellular physiology is not fully understood. The present study aimed at exploring the potential roles of the two dominant functional ion channels, intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium (IKCa) and volume-sensitive chloride (ICl.vol) channels, in regulating proliferation of mouse MSCs. We found that inhibition of IKCa with clotrimazole and ICl.vol with 5-nitro-1-(3-phenylpropylamino) benzoic acid (NPPB) reduced cell proliferation in a concentration-dependent manner. Knockdown of KCa3.1 or Clcn3 with specific short interference (si)RNAs significantly reduced IKCa or ICl.vol density and channel protein and produced a remarkable suppression of cell proliferation (by 24.4 ± 9.6% and 29.5 ± 7.2%, respectively, P < 0.05 vs. controls). Flow cytometry analysis showed that mouse MSCs retained at G0/G1 phase (control: 51.65 ± 3.43%) by inhibiting IKCa or ICl.vol using clotrimazole (2 μM: 64.45 ± 2.20%, P < 0.05) or NPPB (200 μM: 82.89 ± 2.49%, P < 0.05) or the specific siRNAs, meanwhile distribution of cells in S phase was decreased. Western blot analysis revealed a reduced expression of the cell cycle regulatory proteins cyclin D1 and cyclin E. Collectively, our results have demonstrated that IKCa and ICl.vol channels regulate cell cycle progression and proliferation of mouse MSCs by modulating cyclin D1 and cyclin E expression.

Keywords: intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated K+ current, volume sensitive Cl− current, cell cycle progression, short interference RNA

mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) from bone marrow are pluripotent adult stem cells that can differentiate into a broad spectrum of cells, including osteoblasts, chondrocytes, adipocytes, neurons, skeletal muscle cells, and cardiomyocytes (25, 31, 43). Multidisciplinary researchers have paid great attention to MSCs, which have been considered as a source of cells for cell-based therapy in regenerative medicine, especially in repair of damaged myocardium (24, 27).

Clinical trials showed that implantation of human MSCs into infarcted myocardium tissues improved cardiac function (39). Although the therapeutic effects are encouraging, potential proarrhythmic effect of transplanted MSCs was observed in both in vitro and in vivo studies (5). Therefore, the electrophysiological properties of MSCs from different species (i.e., human, rabbit, rat, and mouse) and tissues (i.e., bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, and fat tissue) have recently been studied (1, 8, 9, 13, 22, 23, 30, 37). Results from these studies demonstrated that expression of multiple ion channels was heterogeneous and species dependent (9, 22, 23, 37) or cell cycle dependent (8). This information is important for the application of bone marrow MSCs-based therapy for repairing myocardium; however, the roles of these ion channels in the regulation of stem cell behaviors (e.g., cell proliferation) are not well understood. Our previous study demonstrated that three functional ion channels, intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel (IKCa or KCa3.1), volume-sensitive chloride channel (ICl.vol or Clcn3), and inward rectifier K+ channel (Kir2.1), were present in mouse MSCs (37). IKCa and ICl.vol were recorded in most mouse MSCs (95% and 88%, respectively), while Kir2.1 channel expressed only in a small population of cells (16%). The present study was designed to explore the potential roles of these two dominant ion channels (IKCa and ICl.vol) in regulation of proliferation and cell cycle progression in mouse MSCs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Mouse bone marrow MSCs (passage 5) from C57Bl/6 mice were kindly provided by Dr. Darwin J. Prockop, Center for Gene Therapy, Tulane University (http://www.som.tulane.edu/gene_therapy). Cells tested positive for Sca-1 and negative for CD34, CD45, and CD11B-C surface markers and can be differentiated into adipocytes and osteocytes. MSCs were cultured and passaged as described previously (37). Cells used in this study were from the early passages 6 to 8 to limit the possible variations in functional ion channel currents, gene expression, and protein levels induced by cell aging and senescence in later passages, since it has been reported that cell senescence occurs in later passages of in vitro MSC culture (2, 4).

Drugs and reagents.

The chloride channel blocker 5-nitro-1-(3-phenylpropylamino) benzoic acid (NPPB) was purchased from Tocris (Bristol, UK). Rabbit polyclonal anti-KCa3.1, goat polyclonal anti-Clcn-3, mouse monoclonal anti-cyclin D1 and anti-cyclin E, goat anti-rabbit, donkey anti-goat IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP), and goat polyclonal anti-GAPDH-HRP antibodies were products of Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Other reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Cell proliferation assays.

3-(4,5-Dimethyl-thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was applied to assess the effects of ion channel blockers on cell proliferation (19). Mouse MSCs were plated into 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well in 200 μl complete culture medium. After 8 h recovery, the culture medium containing ion channel blockers was used. Following 72 h incubation, 20 μl PBS-buffered MTT (5 mg/ml) solution was added to each well and the plates were incubated at 37°C for an additional 4 h. The medium was removed, and 100 μl/well DMSO was added to each well to dissolve the purple formazan crystals. The plates were read (wavelengths: test, 570 nm; reference, 630 nm) using a μQuant microplate spectrophotometer (Bio-Tek Instruments). Results were standardized using control group values.

[3H]thymidine incorporation assay was introduced to assess proliferating cell rate (19). Mouse MSCs were plated into 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well in 200 μl complete culture medium. After 8 h recovery, the culture medium was replaced with a medium containing ion channel blockers or specific short interference RNAs (siRNAs) and incubated for 48 h, and 1 μCi (0.037 MBq) [3H]thymidine (GE Healthcare, Hong Kong) was then added into each well. Following an additional 24 h of incubation, cells were harvested and transferred to a nitrocellulose-coated 96-well plate via suction. Nitrocellulose membrane was washed with water flow, and plate was air dried at 50°C overnight. Liquid scintilla (20 μl/well) was then added to each well. Counts per minute (cpm) for each well was read by a TopCount microplate scintillation and luminescence counter (PerkinElmer, Waltharn, MA).

RNA interference.

siRNA molecules targeting different exons of KCa3.1 (i.e., KCNN4 for IKCa) and Clcn3 (for ICl.vol) genes were synthesized by Ambion (Austin, TX). Specific siRNA sequences for target genes are shown in Table 1. A FAM-labeled sequence that had no known target in the mouse genome was used as a negative control (i.e., control siRNA). The siRNA molecules (final concentrations at 50 nM as recommended by the supplier) were transfected into mouse MSCs at 50–60% confluence using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Transfection efficiency was monitored by control siRNA by counting the percentage of fluorescence-bearing cells under a confocal microscope (Olympus FluoView 300) 4 h after transfection. After 72 h of transfection, the cells were used for electrophysiology, RT-PCR, Western blot analysis, and flow cytometrical analysis, respectively.

Table 1.

siRNA sequences for targeting KCa3.1 and Clcn3 genes

| siRNA Sequence (5′–3′) | Target Exon | Molecule Identifier | siRNA Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KCNN4/KCa3.1 | ||||||

| Sense: GGUCCAGCUGUUCAUGACUtt | 2,3 | 62554 | A | |||

| Antisense: AGUCAUGAACAGCUGGACCtc | ||||||

| Sense: GCCUGGAUGUACUACAAGCtt | 6 | 155004 | B | |||

| Antisense: GCUUGUAGUACAUCCAGGCtt | ||||||

| Sense: CGAUAAAUCACCUCAAGAUtt | 9 | 155005 | C | |||

| Antisense: AUCUUGAGGUGAUUUAUCGtg | ||||||

| Clcn3 | ||||||

| Sense: GGACAGAGAAAGGCACAGAtt | 2 | 60763 | A | |||

| Antisense: UCUGUGCCUUUCUCUGUCCtt | ||||||

| Sense: GGCACAGACGGAUCAACAGtt | 2,3 | 60858 | B | |||

| Antisense: CUGUUGAUCCGUCUGUGCCtt | ||||||

| Sense: GGUAUUUAUGAAGCACACAtt | 10 | 60947 | C | |||

| Antisense: UGUGUGCUUCAUAAAUACCtt | ||||||

Electrophysiology.

Membrane ionic currents were recorded using the whole cell patch-clamp technique as described previously (37) using an EPC-10 amplifier and Pulse software (HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany). Briefly, borosilicate glass electrodes (1.2-mm outer diameter) were pulled with a Brown-Flaming puller (model P-97; Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA) and had tip resistances of 2–3 MΩ when filled with pipette solution. Tip potentials were compensated before the pipette touched the cell. After a gigaohm seal was obtained by negative suction, the cell membrane was ruptured by gentle suction to establish whole cell configuration. Membrane currents were low-pass filtered at 5 kHz and stored on the hard disk of an IBM-compatible computer.

For IKCa recording, cells were perfused with Tyrode solution containing (in mM) 136 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.0 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 0.33 NaH2PO4, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.3). The pipette solution contained (in mM) 20 KCl, 110 K-aspartate, 1.0 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 0.1 GTP, 5.0 Na2-phosphocreatine, 5.0 Mg-ATP, and 800 nM free Ca2+ (pH 7.2). For ICl currents recording, cells were initially perfused in 1.0T solution containing (mM) 110 NaCl, 5.0 KCl, 1.0 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES and 60 mannitol (pH 7.3). When whole-cell configuration was obtained, cells were perfused with 0.8T solution (omitted mannitol from 1.0T solution). The pipette solution used for ICl recording contained (mM) 110 CsCl, 20 Cs-aspartate, 5 EGTA, 1.0 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 0.1 GTP, 5.0 Na2-phosphocreatine, 5.0 Mg-ATP. The experiments were conducted at room temperature (22–23°C).

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

Total RNA of mouse MSCs was extracted, and RT-PCR was conducted according to the established protocol as described previously (37). Semiquantitative PCR was run for 30 cycles for KCa3.1 and Clcn3, and 28 cycles for GAPDH as a reference control. The PCR products were resolved through 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis, and the amplified cDNA bands were visualized by ethidium bromide staining and imaged using Chemi-Genius Bio Imaging System (Syngene, Cambridge, UK).

Western blot analysis.

Cells lysates were extracted via a modified RIPA buffer, and protein concentrations were determined by Bio-Rad protein assay. Western blot analysis of protein levels was conducted as previously described (37). To quantitatively analyze ion channel protein levels, membranes were stripped with stripping buffer (62.5 mM Tris, 2% SDS, and 100 mM 2-β-mercaptoethanol; pH adjusted to 6.8) at 55°C for 30 min and were then probed with HRP-conjugated goat polyclonal anti-GAPDH antibody (1:1,000). To develop X-ray films, membranes were prepared using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (GE Healthcare). The expression of GAPDH levels was used as an internal control to standardize the relative levels of KCa3.1 and Clcn3 protein. The relative band intensities of Western blot were measured by quantitative scanning densitometer and image analysis software (Bio-1D version 97.04).

Flow cytometry and cell cycle analysis.

Cell cycle distribution of mouse MSCs was determined by flow cytometry (FC500, Beckman Coulter). Briefly, cells were lifted using 0.25% trypsin, washed with PBS, and fixed with ice-cold ethanol (70%). Ethanol was removed by centrifugation, and cell pellets were washed with PBS. Cells were incubated in a propidium iodide/PBS staining buffer (20 μg/ml propidium iodide, 100 μg/ml RNaseA, and 0.1% Triton X-100) at 37°C for 30 min. Data were acquired using CellQuest software, and the percentages of G0/G1, S, and G2/M phase cells were calculated with MODFIT LT software.

Statistical analysis.

Results are presented as means ± SD. Unpaired Student's t-tests were used as appropriate to evaluate the statistical significance of differences between two group means, and analysis of variance was used for multiple groups. Values of P < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Effects of IKCa and ICl.vol blockade on mouse MSC proliferation.

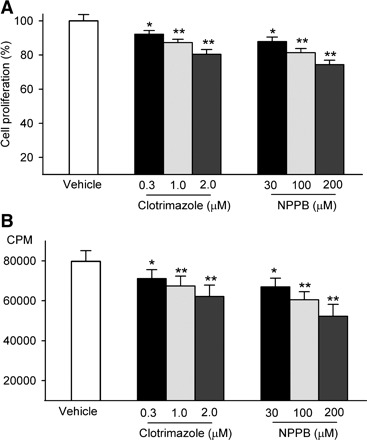

Our previous study showed that clotrimazole and NPPB effectively blocked functional IKCa and ICl.vol in mouse MSCs, respectively (37). These two pharmacological compounds were therefore applied in the present study to investigate cell proliferation. Cell proliferation assessed by MTT assay demonstrated that inhibition of the IKCa by clotrimazole and of the ICl.vol by NPPB resulted in a concentration-dependent reduction of proliferation in mouse MSCs after a 72-h incubation (Fig. 1A). Clotrimazole (2 μM) inhibited the proliferation by 20.5 ± 2.7% (P < 0.01 vs. vehicle control). NPPB (200 μM) reduced the proliferation by 25.5 ± 2.5% (P < 0.01 vs. vehicle control). In addition, [3H]thymidine incorporation assay showed that both clotrimazole and NPPB decreased DNA incorporation rate in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). Clotrimazole (2 μM) inhibited the DNA synthesis rate by 22.0 ± 4.8% (P < 0.01 vs. vehicle), and NPPB (200 μM) decreased the DNA synthesis rate by 34.3 ± 7.8% (P < 0.01 vs. vehicle control). These results suggest that the inhibition of IKCa or ICl.vol decreases proliferation of mouse MSCs.

Fig. 1.

Effect of ion channel blockers on cell proliferation in mouse mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). A: cell proliferation was assessed by 3-(4,5-dimethyl-thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide assay with treatment of clotrimazole or 5-nitro-1-(3-phenylpropylamino) benzoic acid (NPPB). B: cell proliferation was analyzed by [3H]thymidine incorporation assay with treatment of clotrimazole or NPPB. CPM, counts per minute. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. vehicle control.

Effects of siRNAs on ion channel currents, ion channel mRNA, and protein expression.

To exclude the possibility that inhibition of cell proliferation by ion channel blockers is related to a nonselective inhibition of cell proliferation and to ascertain whether activity of IKCa and ICl.vol channels is required for cell proliferation in mouse MSCs, we used the specific siRNA technique to knock down the KCa3.1 (for IKCa) gene or Clcn3 (for ICl.vol) gene. Three specific siRNA molecules targeting different exons of mouse KCa3.1 or Clcn3 mRNA are shown in Table 1. We found that the transfection efficiency of siRNA is very high (>90% cells showing FAM fluorescence in control siRNA group, data not shown).

Figure 2A displays the membrane currents (IKCa) recorded with the protocol shown in the inset using a K+ pipette solution containing 800 nM free Ca2+ in a mouse MSC transfected with 50 nM control siRNA (left) and a cell transfected with 50 nM KCa3.1 siRNA C (right). The current showed a property of inward rectification at potentials positive to +10 mV in cells transfected with control siRNA, typical of IKCa. The current also showed an inward rectification in cells transfected with KCa3.1 siRNA; however, the current amplitude was much smaller than that of control siRNA cells. Current-voltage (I-V) relation curves of IKCa recorded with a ramp voltage protocol from −100 to +60 mV showed an inward rectification in cells transfected with control siRNA and KCa3.1 siRNA (A, B, or C). IKCa density was significantly smaller in cells transfected with KCa3.1 siRNAs than that in cells transfected with control siRNA (Fig. 2B). Figure 2C shows the mean values of IKCa density at +30 mV. IKCa density was significantly suppressed by KCa3.1 siRNA (A, B, or C) transfection (n = 7 for each group, P < 0.01 vs. control siRNA).

Fig. 2.

Effects of short interference (si)RNAs on intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channels (IKCa) and volume-sensitive chloride channels (ICl.vol). A: IKCa was elicited with the protocol shown in the inset using a pipette solution containing 800 nM free Ca2+ in a representative cell transfected with control siRNA (left) and a cell transfected with KCa3.1 siRNA C (right). B: current-voltage (I-V) relationships of membrane currents were recorded using a ramp protocol (−100 to +60 mV) in mouse MSCs transfected with control siRNA (control) or KCa3.1 siRNA (A, B, or C). C: mean values of IKCa at +30 mV in mouse MSCs transfected with control siRNA or KCa3.1 siRNA (A, B, or C). **P < 0.01 vs. control siRNA (n = 7 for each group). D: ICl.vol was recorded with 300-ms voltage steps to between −100 and +80 mV from −40 mV with 0.8T solution perfusion for 20 min in a representative cell transfected with control siRNA (right) and a cell transfected with Clcn3 siRNA C. E: I-V relationships of ICl.vol in mouse MSCs transfected with control siRNA or KCa3.1 siRNA (A, B, or C). F: mean values of ICl.vol at +30 mV in mouse MSCs transfected with control siRNA or Clcn3 siRNA (A, B, or C). **P < 0.01 vs. control siRNA (n = 5 for each group).

Figure 2D shows the membrane current (ICl.vol) recorded with the voltage protocol shown in the inset using a K+-free pipette solution under conditions of 0.8T external solution and symmetrical Cl− in a cell transfected with control siRNA (left) and a cell transfected with Clcn3 siRNA C (right). ICl.vol amplitude was significantly larger in control siRNA cells than that in Clcn3 siRNA cells. The mean value of ICl.vol density was smaller in cells transfected with three types of Clcn3 siRNAs than that in cells transfected with control siRNA at all test potentials (Fig. 2E). Figure 2F displays the mean ICl.vol density at +30 mV in cells transfected with control siRNA or three types of Clcn3 siRNAs (n = 5 for each group, P < 0.01 vs. control siRNA).

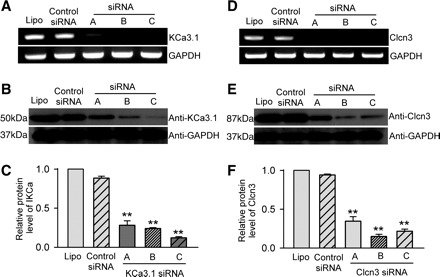

The effects of siRNAs on ion channel mRNA and protein expression were determined by RT-PCR and Western blot analysis, respectively. The mRNA levels of KCa3.1 and Clcn3 were remarkably reduced by the corresponding siRNAs (Fig. 3, A and D). Similarly, the protein levels of KCa3.1 and Clcn3 were also decreased by the corresponding siRNAs (Fig. 3, B and E). The protein levels of KCa3.1 were reduced to 28.21 ± 5.59%, 23.99 ± 1.16%, and 12.14 ± 1.41% by the KCa3.1 siRNA molecules A, B, and C, respectively (P < 0.01 vs. control siRNA), and the protein levels of Clcn3 were reduced to 34.60 ± 5.80%, 14.88 ± 2.81%, and 21.69 ± 2.68% by the Clcn3 siRNA molecules A, B, and C, respectively (P < 0.01 vs. control siRNA).

Fig. 3.

Effects of siRNAs on ion channel mRNA and protein expression. A: KCa3.1 mRNA levels with lipofectamine, control siRNAs, or KCa3.1 siRNA (A, B, or C). B: IKCa channel (KCa3.1) protein levels in cells treated with lipofectamine, control siRNA, or KCa3.1 siRNAs. C: mean values of IKCa (KCa3.1) protein levels in cells treated with lipofectamine, control siRNA, or three KCa3.1 siRNAs (n = 3, **P < 0.01 vs. control siRNA group, relative to GAPDH levels). D: ICl.vol (Clcn3) mRNA levels in cells treated with lipofectamine, control siRNA, or three Clcn3 siRNAs. E: ICl.vol (Clcn3) protein levels in cells treated with lipofectamine, control siRNA, or Clcn3 siRNAs. F: mean values of ICl.vol (Clcn3) protein levels in cells treated with lipofectamine, control siRNA, or three Clcn3 siRNAs. n = 3; **P < 0.01 vs. control siRNA group, relative to GAPDH levels. Lipo, Lipofectamine 2000 transfection group.

Effect of KCa3.1 and Clcn3 knockdown on mouse MSC proliferation.

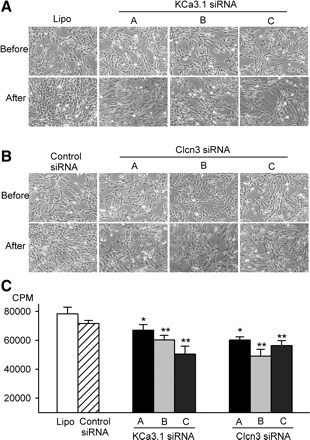

Figure 4 illustrates the effects of knockdown of KCa3.1 or Clcn3 on proliferation in mouse MSCs. All three KCa3.1 siRNAs or Clcn3 siRNAs (50 nM each) remarkably slowed cell growth; the control siRNA had no significant effect on cell growth in mouse MSCs compared with control group with the transfection reagent Lipofectamine 2000 (Fig. 4, A and B). The [3H]thymidine incorporation assay revealed that DNA synthesis rates were significantly slowed by KCa3.1 siRNAs or Clcn3 siRNAs (Fig. 4C). The KCa3.1 siRNA molecules A, B, and C reduced the DNA synthesis rate by 7.55 ± 5.45%, 15.87 ± 4.35%, and 29.60 ± 7.67% (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01 vs. control siRNA), respectively. The Clcn3 siRNA molecules A, B, and C decreased the DNA synthesis rate by 16.00 ± 3.06%, 31.56 ± 6.63%, and 21.29 ± 4.73% (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01 vs. control siRNA), respectively. These data indicate that activity of IKCa and Clcn3 channels is essential in the regulation of cell proliferation.

Fig. 4.

siRNA and mouse MSC proliferation. A: images of mouse MSCs before and after treatment with control siRNA or three types of KCa3.1 siRNAs for 72 h. B: images of mouse MSCs before and after treatment with control siRNA or three types of Clcn3 siRNAs for 72 h. C: DNA incorporation rates in mouse MSCs treated with lipofectamine KCa3.1, or Clcn3 siRNA molecules. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. control siRNA group.

Effects of ion channel blockers and siRNAs on cell cycle progression.

To determine how IKCa and ICl.vol participate in regulating cell proliferation, we used flow cytometry to analyze cell cycle progression with the IKCa inhibitor clotrimazole or the ICl.vol blocker NPPB (Fig. 5A). Figure 5B shows that clotrimazole and NPPB reduced the percentage of cells in S phase (43.04 ± 5.61% for vehicle control; 30.60 ± 4.21% for 2 μM clotrimazole; 12.01 ± 2.03% for 200 μM NPPB, n = 3, P < 0.05 vs. vehicle control) and increased the percentage of cells in G0/G1 phase (51.65 ± 3.34% for vehicle control; 64.45 ± 2.20% for 2 μM clotrimazole; 82.89 ± 2.49% for 200 μM NPPB, n = 3, P < 0.05 vs. vehicle control). The cells in G2/M phase were not affected (5.31 ± 0.57% for control, 4.95 ± 0.62% for 2 μM clotrimazole, and 5.10 ± 1.33% for 200 μM NPPB, P > 0.05 vs. control).

Fig. 5.

Effects of ion channel blockers on cell cycle progression. A: flow cytometry graphs show distribution in cell cycle phases of cells in vehicle control, clotrimazole (2 μM), and NPPB (200 μM) groups. B: mean values of cell distribution percentages at different cell cycle phases in cells treated with clotrimazole (0.3–2 μM) or NPPB (30–200 μM). C: flow cytometry graphs show distribution in cell cycle phases of mouse MSCs treated with control siRNA, KCa3.1 siRNA (molecule C) or Clcn3 siRNA (molecule B). D: mean values of cell distribution percentage at different cycle phases in cells treated with three types of KCa3.1 siRNAs or Clcn3 siRNAs.

The effect of knockdown of IKCa and ICl.vol channels on cell cycle progression was determined by transfecting KCa3.1 and Clcn3 siRNAs into mouse MSCs. Control siRNA had no significant effect on cell cycle progression, compared with Lipofectamine 2000 (Fig. 5, C and D). KCa3.1 siRNAs or Clcn3 siRNAs reduced the cell number in S phase and increased the cell number in G0/G1 phase. The highly efficient KCa3.1 siRNA molecule C or Clcn3 siRNA molecule B caused an accumulation of 68.59 ± 3.72% or 77.30 ± 3.12% cells (control siRNA: 53.47 ± 2.79%, P < 0.05) at G0/G1 phase, an effect comparable with the IKCa inhibitor clotrimazole (2 μM; 64.45 ± 2.20%) or the ICl.vol blocker NPPB (200 μM; 82.89 ± 2.49%), respectively. These results suggest that IKCa and ICl.vol channels regulate cell cycle progression at the G0/G1 transition or the G1/S boundary.

Effects of ion channel blockers and siRNAs on cell cycle regulatory protein expression.

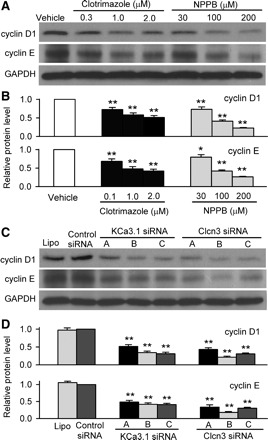

It is generally believed that the cell cycle regulators cyclin D1 and cyclin E play an important role in early G1 and late G1 progression. Therefore, whether the G0/G1 accumulation induced by ion channel blockers or the corresponding siRNAs is related to cyclin D1 and/or cyclin E modulation was examined in mouse MSCs. Clotrimazole and NPPB reduced both cyclin D1 and cyclin E protein levels in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6, A and B). Similarly, KCa3.1 siRNAs or Clcn3 siRNAs also significantly decreased cyclin D1 and cyclin E proteins (Fig. 6, C and D). These results indicate that IKCa and ICl.vol channels participate in the regulation of cell cycle progression by modulating expression of cyclin D1 and cyclin E proteins in mouse MSCs.

Fig. 6.

Effects of channel blockers and siRNAs on expressions of cyclin D1 and cyclin E. A: Western blot images of cyclin D1 and cyclin E expression with clotrimazole and NPPB. B: mean values of protein levels of cyclin D1 and cyclin E in mouse MSCs treated with clotrimazole or NPPB for 72 h (n = 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. vehicle control, relative to GAPDH levels). C: Western blot images of cyclin D1 and cyclin E levels in mouse MSCs treated with lipofectamine, control siRNA, KCa3.1 siRNAs, or Clcn3 siRNAs. D: mean values of cyclin D1 and cyclin E levels in mouse MSCs treated with lipofectamine, control siRNA, KCa3.1 siRNAs, or Clcn3 siRNAs. **P < 0.01 vs. control siRNA group (n = 3), relative to GAPDH levels.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrated that inhibition of IKCa (with clotrimazole) or blockade of ICl.vol (with NPPB) produced a significant reduction of proliferation in mouse MSCs. Similarly, knockdown of KCa3.1 or Clcn3 gene with specific siRNA to decrease IKCa or ICl.vol mRNA and KCa3.1 or Clcn3 protein caused a suppression (20–30%) of mouse MSC proliferation. The cell cycle progression was accumulated at G0/G1 phase by ion channel blockers or siRNAs of IKCa and ICl.vol and was accompanied by a reduced expression of cyclin D1 and cyclin E protein. Our results indicate that both IKCa and ICl.vol channels participate in the regulation of mouse MSC proliferation.

IKCa has been reported in blood cells and in tissues involved in the transport of fluid and ions, including the lung (40), colon (16), and salivary glands (36). In these tissues, IKCa underlies K+ permeability. In addition to this physiological function, IKCa plays an important role in the regulation of proliferation in several types of cells. The involvement of IKCa in cell proliferation was initially described in T lymphocytes (3, 11, 17). Upregulation of IKCa channel is closely related with T lymphocyte activation and consequent cell proliferation, whereas blockade of IKCa inhibits T cell proliferation and ameliorates experimental autoimmune response (3). In addition, IKCa regulates the development and progression of certain cancers (15, 29, 42).

Recent studies reported that IKCa channel participated in the remodeling of smooth muscle cells (38), and block of IKCa channel prevented vascular remodeling induced by either injury (18) or mitogens (35). Significant changes in expression pattern of Ca2+-activated K+ (KCa) channels from intermediate conductance to larger conductance (BKCa) subfamily was observed accompanying the phenotypic conversion of smooth muscle cell from proliferative stage to mature smooth muscle cells (18, 38). In the present study, we found both blockade and knockdown of IKCa channel significantly reduced mouse MSC proliferation (Figs. 1 and 4) and accumulated cell cycle progression at G0/G1 phase (Fig. 5) by downregulating cyclin D1 and cyclin E (Fig. 6). The earlier studies by us and others have shown that KCa channel expression is species dependent. IKCa channel is highly expressed in MSCs from mouse and rat bone marrow (8, 37) but not from human bone marrow (13, 22). These results indicate that IKCa channel is likely a factor that regulates proliferation in mouse (37) or rat MSCs (8), since MSCs derived from these two species go through more passages in culture before senescence than MSCs from humans. Therefore, expression levels of IKCa channel or changes in expression pattern (e.g., from IKCa to BKCa channel) during MSC aging might be an interesting issue to explore in future studies.

It is generally believed that Clcn3 is the candidate for molecular identity of ICl.vol in a variety of mammalian tissues (10, 21, 46). However, some reports have demonstrated that Clcn3 is primarily expressed in intracellular organelles, serves as a H+/Cl− exchanger, and contributes to organelle acidification and secretion in hepatocytes (12) and osteoclasts (26). The activation of Clcn3 is not only volume dependent but also Ca2+/calmodulin dependent (32). Our recent study showed that ICl.vol was activated by hyposmotic challenge and likely encoded by Clcn3 gene in mouse MSCs (37). The present study further demonstrated that knockdown of the Clcn3 gene with specific siRNAs remarkably reduced ICl.vol (Figs. 3 and 4), supporting the notion that Clcn3 encodes ICl.vol in mouse MSCs.

ICl.vol is responsible for regulation of membrane potential in excitable cells and transmembrane Cl− transport in epithelial cells (14, 20) and also plays a role in regulatory volume decrease (20). In addition, ICl.vol has been found to regulate cell proliferation in smooth muscle cells (7, 44); the antisense oligonucleotide specific to Clcn3 reduces proliferation in rat aortic smooth muscle cells (41). In the present study, we demonstrated that blockade of ICl.vol with NPPB or downregulation of Clcn3 with the specific siRNAs significantly reduced cell proliferation (Figs. 1–3) and accumulated cells at G0/G1 phase (Fig. 5); this finding is consistent with recent observations in cancer cells and fibroblasts (6, 34, 45). Our results demonstrated that this effect is related to the downregulation of the cell cycle regulatory proteins cyclin D1 and cyclin E (Fig. 6).

It is generally recognized that as a crucial cellular function, cell proliferation is very strictly controlled by several independent mechanisms (28). The present study showed that blockade or knockdown of IKCa or ICl.vol caused a 20–30% reduction of cell proliferation in mouse MSCs, suggesting that ion channels participate in regulation of cell proliferation but are not a determinant of cell proliferation. Although the detailed mechanisms underlying regulation of cell proliferation by ion channels remain to be clarified, ion channels are believed to regulate cell proliferation by modulating cell membrane potential and/or cell volume. Cell proliferation eventually requires an increase of cell volume. Alterations of cell volume require the participation of ion transport across the cell membrane, including appropriate activity of Cl− and K+ channels (20). Cell volume regulation may maintain appropriate levels of critical factors, e.g., cell cycle regulators: cyclins (D1, -2, and -3 in early G1; E1 and -2 in late G1) and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK 4 and -6 in early G1; CDK 2 in late G1). These factors are necessary for controlling cell cycle progression through G1 to S phase (33). All above potential effects may account for the present observation that IKCa and ICl.vol regulate cell cycle and proliferation by modulating expression of cyclin D1 and cyclin E proteins in mouse MSCs.

GRANTS

This study was supported by the Research Grant Council of Hong Kong (HKU 7347/03M). R. Tao was supported by a postgraduate studentship from the University of Hong Kong.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Darwin J. Prockop, Center for Gene Therapy (supported by National Center for Research Resources Grant P40 RR017447), Tulane University, for providing the mouse MSCs.

Footnotes

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bai X, Ma J, Pan Z, Song YH, Freyberg S, Yan Y, Vykoukal D, Alt E. Electrophysiological properties of human adipose tissue-derived stem cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 293: C1539–C1550, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baxter MA, Wynn RF, Jowitt SN, Wraith JE, Fairbairn LJ, Bellantuono I. Study of telomere length reveals rapid aging of human marrow stromal cells following in vitro expansion. Stem Cells 22: 675–682, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beeton C, Wulff H, Barbaria J, Clot-Faybesse O, Pennington M, Bernard D, Cahalan MD, Chandy KG, Beraud E. Selective blockade of T lymphocyte K+ channels ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, a model for multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 13942–13947, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonab MM, Alimoghaddam K, Talebian F, Ghaffari SH, Ghavamzadeh A, Nikbin B. Aging of mesenchymal stem cell in vitro. BMC Cell Biol 7: 14, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang MG, Tung L, Sekar RB, Chang CY, Cysyk J, Dong P, Marban E, Abraham MR. Proarrhythmic potential of mesenchymal stem sell transplantation revealed in an in vitro coculture model. Circulation 113: 1832–1841, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen LX, Zhu LY, Jacob TJ, Wang LW. Roles of volume-activated Cl− currents and regulatory volume decrease in the cell cycle and proliferation in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Cell Prolif 40: 253–267, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dai YP, Bongalon S, Hatton WJ, Hume JR, Yamboliev IA. ClC-3 chloride channel is upregulated by hypertrophy and inflammation in rat and canine pulmonary artery. Br J Pharmacol 145: 5–14, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deng XL, Lau CP, Lai K, Cheung KF, Lau GK, Li GR. Cell cycle-dependent expression of potassium channels and cell proliferation in rat mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow. Cell Prolif 40: 656–670, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deng XL, Sun HY, Lau CP, Li GR. Properties of ion channels in rabbit mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 348: 301–309, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duan D, Winter C, Cowley S, Hume JR, Horowitz B. Molecular identification of a volume-regulated chloride channel. Nature 390: 417–421, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghanshani S, Wulff H, Miller MJ, Rohm H, Neben A, Gutman GA, Cahalan MD, Chandy KG. Up-regulation of the IKCa1 potassium channel during T-cell activation. Molecular mechanism and functional consequences. J Biol Chem 275: 37137–37149, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hara-Chikuma M, Yang B, Sonawane ND, Sasaki S, Uchida S, Verkman AS. ClC-3 chloride channels facilitate endosomal acidification and chloride accumulation. J Biol Chem 280: 1241–1247, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heubach JF, Graf EM, Leutheuser J, Bock M, Balana B, Zahanich I, Christ T, Boxberger S, Wettwer E, Ravens U. Electrophysiological properties of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Physiol 554: 659–672, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hume JR, Duan D, Collier ML, Yamazaki J, Horowitz B. Anion transport in heart. Physiol Rev 80: 31–81, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jager H, Dreker T, Buck A, Giehl K, Gress T, Grissmer S. Blockage of intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels inhibit human pancreatic cancer cell growth in vitro. Mol Pharmacol 65: 630–638, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joiner WJ, Basavappa S, Vidyasagar S, Nehrke K, Krishnan S, Binder HJ, Boulpaep EL, Rajendran VM. Active K+ secretion through multiple KCa-type channels and regulation by IKCa channels in rat proximal colon. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 285: G185–G196, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khanna R, Chang MC, Joiner WJ, Kaczmarek LK, Schlichter LC. hSK4/hIK1, a calmodulin-binding KCa channel in human T lymphocytes. Roles in proliferation and volume regulation. J Biol Chem 274: 14838–14849, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohler R, Wulff H, Eichler I, Kneifel M, Neumann D, Knorr A, Grgic I, Kampfe D, Si H, Wibawa J, Real R, Borner K, Brakemeier S, Orzechowski HD, Reusch HP, Paul M, Chandy KG, Hoyer J. Blockade of the intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel as a new therapeutic strategy for restenosis. Circulation 108: 1119–1125, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krampera M, Pasini A, Rigo A, Scupoli MT, Tecchio C, Malpeli G, Scarpa A, Dazzi F, Pizzolo G, Vinante F. HB-EGF/HER-1 signaling in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells: inducing cell expansion and reversibly preventing multilineage differentiation. Blood 106: 59–66, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lang F, Foller M, Lang K, Lang P, Ritter M, Vereninov A, Szabo I, Huber SM, Gulbins E. Cell volume regulatory ion channels in cell proliferation and cell death. Methods Enzymol 428: 209–225, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemonnier L, Shuba Y, Crepin A, Roudbaraki M, Slomianny C, Mauroy B, Nilius B, Prevarskaya N, Skryma R. Bcl-2-dependent modulation of swelling-activated Cl− current and ClC-3 expression in human prostate cancer epithelial cells. Cancer Res 64: 4841–4848, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li GR, Sun H, Deng X, Lau CP. Characterization of ionic currents in human mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow. Stem Cells 23: 371–382, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li GR, Deng XL, Sun H, Chung SSM, Tse HF, Lau CP. Ion channels in mesenchymal stem cells from rat bone marrow. Stem Cells 24: 1519–1528, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liao R, Pfister O, Jain M, Mouquet F. The bone marrow–cardiac axis of myocardial regeneration. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 50: 18–30, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Makino S, Fukuda K, Miyoshi S, Konishi F, Kodama H, Pan J, Sano M, Takahashi T, Hori S, Abe H, Hata J, Umezawa A, Ogawa S. Cardiomyocytes can be generated from marrow stromal cells in vitro. J Clin Invest 103: 697–705, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okamoto F, Kajiya H, Toh K, Uchida S, Yoshikawa M, Sasaki S, Kido MA, Tanaka T, Okabe K. Intracellular ClC-3 chloride channels promote bone resorption in vitro through organelle acidification in mouse osteoclasts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 294: C693–C701, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orlic D, Hill JM, Arai AE. Stem cells for myocardial regeneration. Circ Res 91: 1092–1102, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pardo LA. Voltage-gated potassium channels in cell proliferation. Physiology (Bethesda) 19: 285–292, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parihar AS, Coghlan MJ, Gopalakrishnan M, Shieh CC. Effects of intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel modulators on human prostate cancer cell proliferation. Eur J Pharmacol 471: 157–164, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park KS, Jung KH, Kim SH, Kim KS, Choi MR, Kim Y, Chai YG. Functional expression of ion channels in mesenchymal stem cells derived from umbilical cord vein. Stem Cells 25: 2044–2052, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, Moorman MA, Simonetti DW, Craig S, Marshak DR. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 284: 143–147, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson NC, Huang P, Kaetzel MA, Lamb FS, Nelson DJ. Identification of an N-terminal amino acid of the CLC-3 chloride channel critical in phosphorylation-dependent activation of a CaMKII-activated chloride current. J Physiol 556: 353–368, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shankland SJ, Wolf G. Cell cycle regulatory proteins in renal disease: role in hypertrophy, proliferation, and apoptosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278: F515–F529, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen MR, Chou CY, Ellory JC. Swelling-activated taurine and K+ transport in human cervical cancer cells: association with cell cycle progression. Pflügers Arch 441: 787–795, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shepherd MC, Duffy SM, Harris T, Cruse G, Schuliga M, Brightling CE, Neylon CB, Bradding P, Stewart AG. KCa3.1 Ca2+-activated K+ channels regulate human airway smooth muscle proliferation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 37: 525–531, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stummann TC, Poulsen JH, Hay-Schmidt A, Grunnet M, Klaerke DA, Rasmussen HB, Olesen SP, Jorgensen NK. Pharmacological investigation of the role of ion channels in salivary secretion. Pflügers Arch 446: 78–87, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tao R, Lau CP, Tse HF, Li GR. Functional ion channels in mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 293: C1561–C1567, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tharp DL, Wamhoff BR, Turk JR, Bowles DK. Upregulation of intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel (IKCa1) mediates phenotypic modulation of coronary smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2493–H2503, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tse HF, Kwong YL, Chan JK, Lo G, Ho CL, Lau CP. Angiogenesis in ischaemic myocardium by intramyocardial autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell implantation. Lancet 361: 47–49, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vazquez E, Nobles M, Valverde MA. Defective regulatory volume decrease in human cystic fibrosis tracheal cells because of altered regulation of intermediate conductance Ca2+-dependent potassium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 5329–5334, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang GL, Wang XR, Lin MJ, He H, Lan XJ, Guan YY. Deficiency in ClC-3 chloride channels prevents rat aortic smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circ Res 91: E28–E32, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang ZH, Shen B, Yao HL, Jia YC, Ren J, Feng YJ, Wang YZ. Blockage of intermediate-conductance-Ca(2+) -activated K+ channels inhibits progression of human endometrial cancer. Oncogene 26: 5107–5114, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woodbury D, Schwarz EJ, Prockop DJ, Black IB. Adult rat and human bone marrow stromal cells differentiate into neurons. J Neurosci Res 61: 364–370, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiao GN, Guan YY, He H. Effects of Cl− channel blockers on endothelin-1-induced proliferation of rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Life Sci 70: 2233–2241, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng YJ, Furukawa T, Tajimi K, Inagaki N. Cl− channel blockers inhibit transition of quiescent (G0) fibroblasts into the cell cycle. J Cell Physiol 194: 376–383, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou JG, Ren JL, Qiu QY, He H, Guan YY. Regulation of intracellular Cl− concentration through volume-regulated ClC-3 chloride channels in A10 vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 280: 7301–7308, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]