Abstract

Background:

Genomic rearrangements at the fragile site FRA1E may disrupt the dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene (DPYD) which is involved in 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) catabolism. In triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), a subtype of breast cancer frequently deficient in DNA repair, we have investigated the susceptibility to acquire copy number variations (CNVs) in DPYD and evaluated their impact on standard adjuvant treatment.

Methods:

DPYD CNVs were analysed in 106 TNBC tumour specimens using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) analysis. Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) expression was determined by immunohistochemistry in 146 tumour tissues.

Results:

In TNBC, we detected 43 (41%) tumour specimens with genomic deletions and/or duplications within DPYD which were associated with higher histological grade (P=0.006) and with rearrangements in the DNA repair gene BRCA1 (P=0.007). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed low, moderate and high DPD expression in 64%, 29% and 7% of all TNBCs, and in 40%, 53% and 7% of TNBCs with DPYD CNVs, respectively. Irrespective of DPD protein levels, the presence of CNVs was significantly related to longer time to progression in patients who had received 5-FU- and/or anthracycline-based polychemotherapy (hazard ratio=0.26 (95% CI: 0.07–0.91), log-rank P=0.023; adjusted for tumour stage: P=0.037).

Conclusion:

Genomic rearrangements in DPYD, rather than aberrant DPD protein levels, reflect a distinct tumour profile associated with prolonged time to progression upon first-line chemotherapy in TNBC.

Keywords: DPYD, BRCA1, copy number changes, fragile sites, triple-negative breast cancer

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease encompassing different subtypes with distinct biological phenotypes and clinical profiles. Among these, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) accounts for 15–20% of all breast cancer cases. This subtype is defined by loss of oestrogen- and progesterone receptor (ER and PR) expression as well as lack of human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) amplification (Kang et al, 2008; Reis-Filho and Tutt, 2008). The majority of TNBCs also exhibit basal-like features. Owing to the absence of specific therapeutic targets such as ER or HER2, adjuvant treatment currently consists of cytotoxic chemotherapy only. Those TNBC patients who do not respond to chemotherapy have an even worse outcome compared with chemoresistant non-TNBC patients (Dent et al, 2007; Gluz et al, 2009; Linn and Van 't Veer, 2009; Chacon and Costanzo, 2010). A challenging field is, therefore, the identification of TNBC patients with tumours that are likely to be responsive or resistant to first-line chemotherapy. Individuals with an unfavourable molecular-genetic tumour profile would be potential candidates for alternative treatment modalities exploiting novel molecular targets (Tutt et al, 2010; Fost et al, 2011; Mehta et al, 2011).

Several studies have revealed that a significant number of patients with TNBC respond well to standard treatment with 5-FU and/or anthracyclines (Liedtke et al, 2008; Gluz et al, 2009). More recent studies (Colleoni et al, 2010; Wang et al, 2011) suggested also benefit from the classical CMF (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, 5-FU) regimen in TNBC. Regarding the efficacy of chemotherapy regimens based on 5-FU or increasingly prescribed oral 5-FU prodrugs, the key enzyme in the catabolism of (fluoro)pyrimidines is dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD). More than 80% of the administered 5-FU is degraded by DPD, thus requiring high standard dosages of the drug (Lu et al, 1993). Low tumoural DPD expression was, therefore, supposed to increase the response rates upon 5-FU treatment (Etienne et al, 1995; Salonga et al, 2000), but the molecular mechanisms leading to altered DPD concentrations in tumour tissues are largely unknown.

In this context, the detection of the common fragile site FRA1E which extends over 370 kb within the dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene (DPYD) was an important finding, demonstrating a potential mechanism for modifying DPD levels (Hormozian et al, 2007). Common fragile sites are instable chromosomal structures with high DNA torsional flexibility (Schwartz et al, 2006) leading to genomic translocations, amplifications or deletions in case of replication stress. We have recently characterised large intragenic rearrangements within DPYD that occurred in individuals presenting with profound or partial DPD deficiency (van Kuilenburg et al, 2009; van Kuilenburg et al, 2010). However, these events revealed to be extremely rare in the germline (Ticha et al, 2009; Pare et al, 2010). As enhanced fragility of common fragile sites has been observed in cancer cells (Arlt et al, 2006), it is conceivable that TNBC tumours which are frequently deficient in BRCA1-mediated DNA repair (Turner and Reis-Filho, 2006; Turner et al, 2007; Rodriguez et al, 2010; Weigman et al, 2012), might be especially susceptible to acquire somatic rearrangements including the DPYD locus. Consequently, disruption of the DPYD gene may have implications for treatment of TNBC with 5-FU containing therapy regimens.

On the basis of these hypotheses, we have evaluated the presence or absence of DPYD copy number variations (CNVs) in TNBC tumour specimens. In this retrospective study, we show that genomic DPYD rearrangements occur frequently and are associated with better patient outcome in TNBC, while mere DPD protein levels did not influence clinical outcome.

Patients and methods

Patients and tumour specimens

One hundred and six fresh-frozen tumour specimens of patients diagnosed with primary TNBC, stored in liquid nitrogen at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technische Universität München, were available for studies using high-molecular-weight DNA (cohort 1). Tumour content of the specimens was generally 70% or higher. In addition, nine tissue microarrays (TMAs) which were constructed from paraffin-embedded tumour material of 146 TNBC patients, archived at the Institute of Pathology, Technische Universität München, were used for immunohistochemical analyses (cohort 2). In 34 cases, matched fresh-frozen and paraffin-embedded tumour samples were available from the same patient. The patient samples had been collected after surgery between 1988 and 2009 and had been classified and assessed for steroid hormone receptor (ER and PR) and HER2 expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC) (Aubele et al, 2007). Hormone receptor status was defined as negative when less than or equal to 3/12 nuclear staining (Remmele's score) was observed. Tumours were classified as HER2-negative when assigned as 0 or 1+ by IHC staining and/or lacking of HER2 amplification in FISH staining (according to ASCO guidelines). Samples collected before 1999 were retrospectively assessed for HER2 expression by IHC.

Clinical parameters of the studied patient panels are listed in Tables 1A and 1B. Approximately 80% of the tumour specimens were classified as invasive-ductal carcinoma of no special type and were categorised in the high-grade group (G3) according to the classification of Elston and Ellis (Elston and Ellis, 1991). Patients had received treatment following the guidelines at the time of diagnosis. For patient cohort 1, follow-up data were recorded for up to 203 months and were available for 91 patients including 69 patients treated with standard 5-FU- and/or anthracycline-based polychemotherapy and 65 patients who had received radiotherapy. The 5-year overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (time to progression (TTP)) rates in patients treated with polychemotherapy were 81±4.7% (standard error SE) and 76±5.5%, respectively. For patient cohort 2, 105 cases with follow-up data up to 244 months were available. Sixty-eight of these patients had received 5-FU- and/or anthracycline-based polychemotherapy and showed 5-year OS and progression-free survival (TTP) rates of 80±5.1% and 65±6.1%, respectively. Patients with neoadjuvant treatment were excluded from survival calculations.

Table 1A. Clinical data and DPYD CNV.

| |

|

|

DPYD

CNVs (% patients) |

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | n | Valid % | Yes | No | P |

| Cohort 1 |

106 |

|

n=43 |

n=63 |

|

|

Age | |||||

| <50 | 41 | 39.8 | 41.9 | 38.3 | |

| ⩾50 | 62 | 60.2 | 58.1 | 61.7 | 0.718 |

| Unknown |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

Tumour stage | |||||

| pT1+pT2 | 86 | 84.3 | 87.8 | 81.7 | |

| pT3+pT4 | 16 | 15.7 | 12.2 | 18.3 | 0.407 |

| Unknown |

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

Nodal status | |||||

| N0 | 51 | 52.0 | 58.5 | 48.3 | |

| Node-positive | 47 | 48.0 | 41.5 | 51.7 | 0.314 |

| Unknown |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

Histological grade | |||||

| 1+2 | 23 | 23.0 | 9.5 | 32.8 | |

| 3 | 77 | 77.0 | 90.5 | 67.2 | 0.006a |

| Unknown |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

Histology | |||||

| Invasive ductal | 82 | 80.4 | 80.9 | 80.0 | |

| Medullary | 6 | 5.9 | 7.1 | 5.0 | |

| Other | 14 | 13.7 | 11.9 | 15.0 | 0.732 |

| Unknown |

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

BRCA1 CNVs | |||||

| Yes | 63 | 70.0 | 87.5 | 60.3 | |

| No | 27 | 30.0 | 12.5 | 39.7 | 0.007a |

| Unknown |

16 |

|

|

|

|

|

Chemotherapy | |||||

| None | 19 | 19.4 | 14.6 | 22.8 | |

| FEC | 27 | 27.6 | 29.3 | 26.3 | |

| CMF | 16 | 16.3 | 22.0 | 12.3 | |

| EC-CMF | 4 | 4.1 | 4.8 | 3.5 | |

| EC | 21 | 21.4 | 19.5 | 22.8 | |

| Other | 11 | 11.2 | 9.7 | 12.3 | 0.714 |

| Unknown | 8 | ||||

Abbreviations: CMF=cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, 5-FU; CNVs=copy number variations; DPYD=dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase; EC=epirubicin, cyclophosphamide; FEC, 5-FU=epirubicin, cyclophosphamide.

Statistically significant.

DPYD CNVs included 21 deletions and 19 duplications (see text).

BRCA1 CNVS included 60 deletions, two intragenic duplications and one gene duplication associated with a mutation.

Written informed consent for the use of tissue samples for research purposes was obtained from all patients. Approval for use of the tumour samples was received from the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the Technische Universität München.

DNA preparation

Nuclear fractions were prepared from frozen TNBC specimens after routine separation of cytosol preparations by ultracentrifugation (Janicke et al, 1994). High-molecular weight DNA was extracted from nuclear fractions by using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Five blood samples of healthy donors were prepared with the same kit and used as control samples for multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) analysis.

MLPA analysis

The MLPA test for DPYD (P103-B1, MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) is composed of 38 probes for DPYD, including one probe for detecting the c.1905+1G>A mutation, and nine control probes specific for DNA sequences outside the DPYD gene. The MLPA test was performed as described before (Schouten et al, 2002; van Kuilenburg et al, 2010) using 50–200 ng of DNA per reaction. Data analysis was performed using GeneMapper software (Applied Biosystems, Nieuwekerk a/d IJssel, The Netherlands). The relative peak area was determined by dividing the mean of the peak areas of the control probes of each sample by the mean of the peak areas of the control probes of all the samples (Rcontrol). The peak area of each DPYD MLPA probe of a sample was divided by the Rcontrol of that sample. Subsequently, the relative peak area of each DPYD probe was divided by the average relative peak area of this probe in all the tumour samples. In unaffected individuals, this will result in a value of 1 (100%) representing two copies of the target sequence in the sample. According to the manufacturer's recommendations, we applied cut-off values for each probe ratio of <0.70 and>1.30, respectively, to define reduced or increased copy numbers of the target sequence. As the MLPA test enables detection of an aberration in a region covered by multiple MLPA probes if 20% or even less aberrant tumour cells are present (Hömig-Hölzel and Savola, 2012), we additionally included samples with a mean probe ratio of all DPYD probes below ⩽0.85 or above ⩾1.15, indicative for a cell fraction with deletion or duplication of the whole coding region. Samples were analysed in duplicate runs and five blood samples were included as reference.

The MLPA test for BRCA1 (P002-C1, MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) contains 26 probes for BRCA1 and 9 control probes specific for DNA sequences outside the BRCA1 gene. The relative peak areas were determined as described above. Subsequently, the relative peak area of each BRCA1 probe was divided by the average relative peak area of this probe obtained from five blood samples.

Generation of anti-DPD antiserum

Human DPYD cDNA was cloned into the Nco I/Bgl II restriction sites of a pQE-60 vector (Qiagen) including a polyhistidine (His6)-tag at the C-terminus. The recombinant protein was expressed in Escherichia coli cells and subsequently purified by nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid sepharose chromatography (Qiagen) according to standard procedures. Following dialysis and re-naturation in phosphate-buffered saline, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.4, two rabbits were immunised with this protein preparation. Anti-DPD antibodies were affinity-purified by coupling the immunogen preparation to a mixture of 50%/50% AffiGel-10 and AffiGel-15 (BioRad, München, Germany). Elution was performed with 0.1 M glycine/HCl buffer pH 2.4, followed by re-neutralisation to pH 7.4. Finally, antibodies were concentrated by ultrafiltration with Ultracell 50 K (Merck Millipore, Schwalbach, Germany) and diluted 50%/50% (v/v) with glycerol for storage. All batches were checked by one-site ELISA using DPD coated on microplates. Immunoreactivity with the specific DPD band at ∼105 kDa was confirmed by western blot using protein preparations obtained from E. coli cells expressing the recombinant protein as well as from peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Immunohistochemistry

DPD protein expression was measured by IHC using TMAs (Aubele et al, 2007). Tissue microarray sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated through a graded ethanol series finishing with distilled water. Endogenous peroxidase was inhibited by treatment with 3% hydrogen peroxide. The affinity-purified rabbit anti-DPD antiserum was applied in a dilution of 1 : 300 and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in humidified chambers. Staining was performed with the Dako EnVision Detection System (Dako, Hamburg, Germany) which uses a peroxidase-conjugated polymer backbone coupled to secondary antibody molecules, and diaminobenzidine (DAB+) as chromogenic substrate. Nuclei of the cells were finally counterstained with haematoxylin. Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase staining intensity was assigned as absent (0), low (1+), moderate (2+) or strong (3+) staining. To confirm the adequacy of the immunohistochemical staining, mammary ductal epithelium (Kamoshida et al, 2005) and liver tissue (Ho et al, 1986; Gerlach et al, 2011) were used as positive controls known to exhibit high amounts of DPD protein or mRNA. Furthermore, an additional breast cancer tissue section was included in each run as negative control by omission of primary antibody (Punsawad et al, 2013).

Statistics

Data independently obtained from MLPA and IHC analyses were merged at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technische Universität München. Statistical analysis was performed with the IBM SPSS Statistics software version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The OS and TTP were considered as long-term endpoints. The OS was defined as the time from surgery until death from any cause and TTP was defined as the time from surgery to the first incidence of disease recurrence (local or distant). The Cox proportional hazard model was used to assess univariate and multivariable explanatory ability of the clinical or molecular parameters with respect to OS and TTP. Survival curves were generated according to the Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test was used for statistical comparison of event-time distributions between independent subgroups. Ninety-five per cent confidence intervals were provided for relevant effect estimates such as hazard ratios (HRs). Association of molecular and categorical clinical data was assessed by the Chi-square test. All statistical tests were conducted two-sided and a P-value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. To retain a maximum of power in the primary interesting analyses, no correction of P-values was applied to adjust for multiple testing (Saville, 1990). This study was designed following the reporting recommendations for tumour marker prognostic studies (REMARK) (McShane et al, 2006; Altman et al, 2012).

Results

DPYD CNVs occur frequently in TNBC tumour specimens

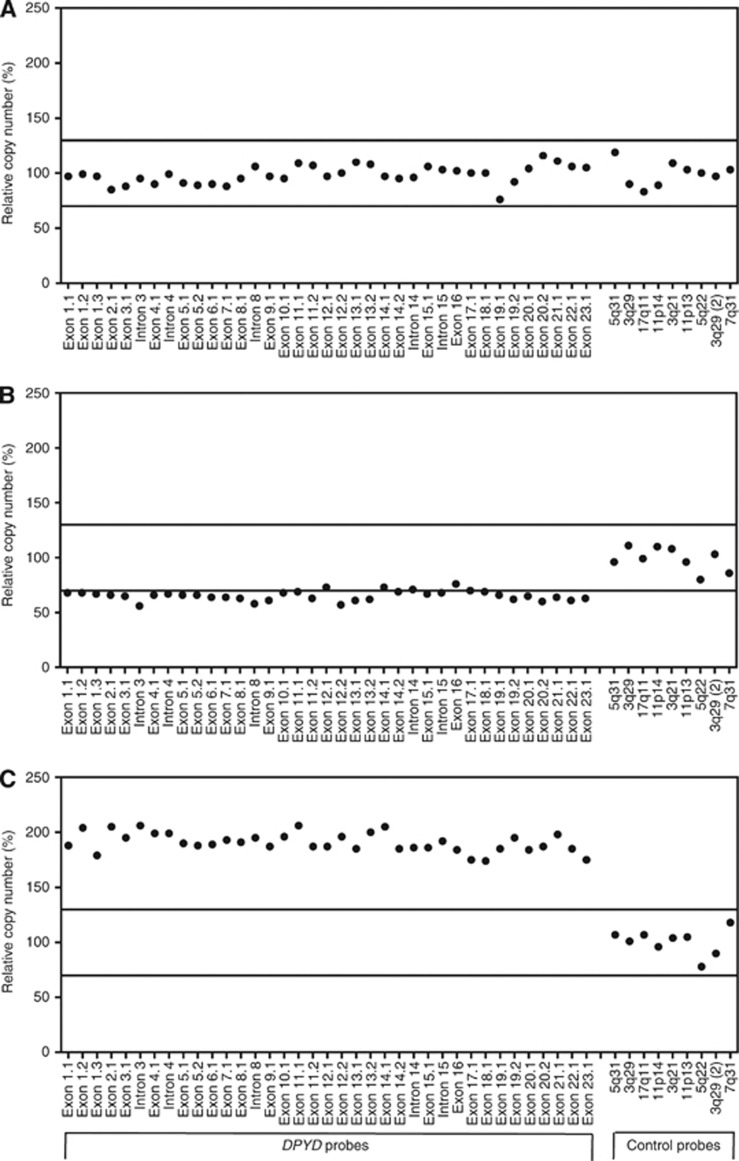

One hundred and six fresh-frozen TNBC specimens (cohort 1) were analysed by MLPA to investigate the prevalence of large rearrangements within the DPYD gene. We detected CNVs of DPYD exons in 43 tumour specimens (41%, 95% CI: 31–51%). Eleven samples exhibited breakpoints within the FRA1E block spanning DPYD exons 13–16, a region supposed to display highest recombination frequency (Hormozian et al, 2007). Overall, however, gains or losses were observed throughout the entire gene without apparent hotspots. Six of 19 duplications and 11 of 21 deletions extended over the whole DPYD coding sequence as exemplarily illustrated in Figure 1. Furthermore, three TNBC samples showed a more complex pattern with large deleted as well as amplified regions within the gene.

Figure 1.

Analysis of copy number changes in DPYD using MLPA. The results of the quantitative analysis of the copy number of the 23 coding exons and 4 intronic sequences of DPYD and 9 control probes specific for DNA sequences outside DPYD is shown for a patient with no aberrations (panel A), deletion of the entire DPYD gene (panel B) and amplification of the entire DPYD gene (panel C). The solid lines represent the cut-off values indicative for amplification (relative copy number >1.3) or deletion (relative copy number<0.7) of that particular sequence.

As expected, DPYD CNVs were predominantly found in the group of high-grade (G3) tumours (Table 1A; P=0.006). Interestingly, we also observed a significant association of DPYD CNVs with the incidence of reduced/aberrant copies of BRCA1 (P=0.007). Age, tumour stage or nodal status (binary variables) were not significantly linked to DPYD CNVs (Table 1A).

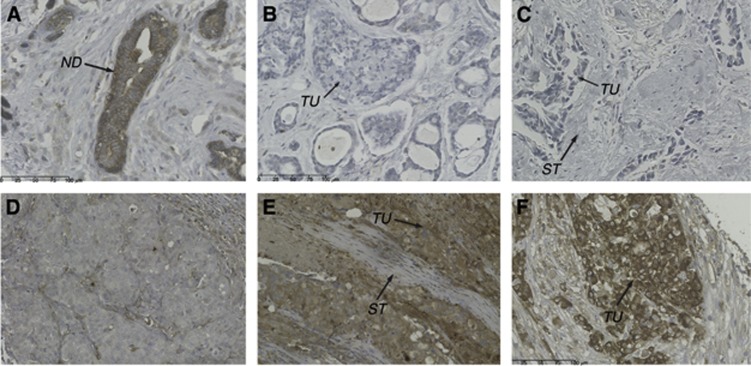

DPD protein expression is frequently downregulated in TNBC tumour specimens

We assessed the DPD expression status in TNBC tissues (cohort 2) using IHC. For this purpose, nine TMAs containing tumour tissue sections of 146 triple-negative and 20 triple-positive breast cancer (TPBC) patients were constructed. A broad range of cytoplasmic staining with the anti-DPD antibody was observed ranging from undetectable (0) to strong (3+) staining (Figure 2A–F). Normal ductal epithelium (panel A) or intraductal carcinoma exhibited strong (3+) staining. Compared with ductal epithelia, the majority of TNBC (64%) as well as TPBC (90%) tumour specimens showed profound downregulation of DPD protein levels (score 0-1+). Moreover, we observed lower DPD expression in higher stage tumours (pT3+pT4 categories) exhibiting statistical significance (P=0.003; Table 1B and Table 2).

Figure 2.

DPD protein expression assessed by immunohistochemical staining of TNBC specimens with anti-DPD. DPD expression was measured by immunohistochemistry using an affinity-purified anti-DPD antibody. Tissue microarray sections with different staining intensity are shown. (A) Section showing normal ductal epithelium with strong (3+) DPD staining. (B, C) Invasive breast cancer of no special type (NST) with undetectable DPD expression; parallel analysis of the DPYD gene in (B) revealed large deleted and amplified regions within the coding sequence. (D) Invasive breast cancer, NST, with low (1+) DPD expression. (E) Invasive breast cancer, NST, showing moderate (2+) DPD expression of tumour cells; parallel analysis of the DPYD gene suggested the presence of a duplication (mean copy number=150% of normal control). (F) Invasive breast cancer, NST, showing strong DPD expression assigned as 3+. Abbreviations: ND=normal ductal epithelium; ST=stroma; TU=tumour cells.

Table 1B. Clinical data and DPD protein expression (IHC).

| |

|

|

DPD expression score (% patients) |

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | n | Valid % | 0–1+ | 2-3+ | P |

| Cohort 2 |

146 |

|

n=93 |

n=53 |

|

|

Age | |||||

| <50 | 39 | 28.7 | 25.0 | 35.4 | |

| ⩾50 | 97 | 71.3 | 75.0 | 64.6 | 0.199 |

| Unknown |

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

Tumour stage | |||||

| pT1+pT2 | 107 | 76.4 | 68.2 | 90.4 | |

| pT3+pT4 | 33 | 23.6 | 31.8 | 9.6 | 0.003a |

| Unknown |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

Nodal status | |||||

| N0 | 59 | 45.4 | 45.2 | 45.7 | |

| Node-positive | 71 | 54.6 | 54.8 | 54.3 | 0.964 |

| Unknown |

16 |

|

|

|

|

|

Histological grade | |||||

| 1+2 | 17 | 12.7 | 14.3 | 10.0 | |

| 3 | 117 | 87.3 | 85.7 | 90.0 | 0.471 |

| Unknown |

12 |

|

|

|

|

|

Histology | |||||

| Invasive ductal | 115 | 80.4 | 76.7 | 86.8 | |

| Medullary | 18 | 12.6 | 13.3 | 11.3 | |

| Other | 10 | 7.0 | 10.0 | 1.9 | 0.277 |

| Unknown |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

Chemotherapy | |||||

| None | 54 | 37.5 | 42.9 | 28.3 | |

| FEC | 26 | 18.1 | 16.5 | 20.8 | |

| CMF | 21 | 14.6 | 14.3 | 15.1 | |

| EC-CMF | 7 | 4.9 | 4.4 | 5.7 | |

| EC | 24 | 16.7 | 15.4 | 18.9 | |

| Other | 12 | 8.4 | 6.6 | 11.4 | 0.744 |

| Unknown | 2 | ||||

Abbreviations: CMF=cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, 5-FU; DPYD=dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase; EC=epirubicin, cyclophosphamide; FEC=5-FU, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide; IHC=immunohistochemistry.

Statistically significant.

Table 2. DPD protein expression scores determined by IHC.

| |

|

DPD expression score (IHC) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Low (0–1+) n (%) | Moderate (2+) n (%) | High (3+) n (%) | |

| TNBC (all) |

146 |

93 (64) |

42 (29) |

11 (7) |

|

TNBCs with DPYD CNVsa,b | ||||

| Deletion | 9 | 4 (44) | 4 (44) | 1 (11) |

| Duplication | 6 | 2 (33) | 4 (67)c | 0 |

| No CNV |

19 |

12 (63) |

6 (32) |

1 (5) |

|

Comparative tissue | ||||

| TPBC | 20 | 18 (90) | 2 (10) | |

Abbreviations: CNV=copy number variation; DPYD=dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene; IHC=immunohistochemistry; TNBC=triple-negative breast cancer; TPBC=triple-positive breast cancer (hormone receptor-positive and HER2-positive).

Matched cases of TNBC specimens examined for DPD expression and DPYD CNV.

Correlation of copy number data with low versus moderate/high protein scores: P=0.461 (Fisher's exact test).

Two out of four cases consisted of duplications of the entire coding region.

To evaluate the DPD expression status in TNBCs with or without DPYD CNVs, we defined the staining pattern in 34 matched cases for which both IHC and MLPA data were available (Table 2). Loss of heterozygosity in the DPYD gene was indeed accompanied by low (0-1+) to moderate (2+) DPD staining in all except one tumour sample. Similarly, cancers exhibiting duplications were predominantly (67%) associated with moderate (2+) DPD staining. One TNBC sample with a complex pattern of deleted and amplified sequences showed total loss of DPD protein (see also Figure 2B and E). Nevertheless, DPD expression scores and MLPA data did not reveal a statistical correlation (P=0.461) as tumour specimens without any DPYD rearrangements showed a broad spectrum of DPD staining as well ranging from undetectable up to high expression levels (Table 2).

As low DPD expression has been suggested to increase the response rates in cancer patients treated with the fluoropyrimidine drug 5-FU, we analysed outcome in TNBC patients who had received adjuvant treatment. However, even in the subgroup of patients treated with 5-FU-based chemotherapy only (n=46), we did not observe a clinical benefit from low (0-1+) DPD protein expression compared with moderate and high expression for TTP (5-year TTP with low DPD expression: 65.5±8.8% moderate expression: 82.5±11.3% strong expression: 75.0±21.7% log-rank P=0.383).

DPYD CNVs have prognostic value and are associated with longer TTP

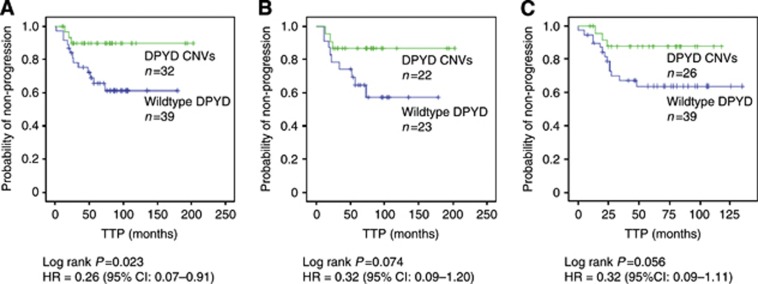

We next assessed the impact of DPYD CNVs (applied as combined status of deletions or duplications) on TTP and OS (Table 3). In the patient subgroup treated with standard adjuvant polychemotherapy (cohort 1), 32 of 69 TNBCs showed genomic DPYD rearrangements which were significantly associated with a reduced risk of disease progression (HR=0.26 [95% CI: 0.07–0.91], log-rank P=0.023) (Figure 3A). Tumour stage revealed to be the only prognostic clinical parameter for TTP in the univariate analysis (Table 3). Adjusted for tumour stage, the DPYD status remained to be an independent parameter providing additional prognostic information (P=0.037). Moreover, in the multivariable model including the most important established clinical factors (age, histological grading, nodal status and tumour stage) (Table 4A), DPYD CNVs and tumour stage maintained statistical significance as well although the small number of events (n=16) may weaken the power of this model. The DPYD status did not provide prognostic information independent of the BRCA1 status (Table 4B) underlining the observed association of DPYD and BRCA1 CNVs.

Table 3. Effect of clinical and molecular-genetic parameters on outcome of patients treated with 5-FU and/or anthracycline-based therapy.

| |

TTP (n=69) |

OS (n=73) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | Log-rank p | HR | 95% CI | Log-rank p |

|

Age | ||||||

| <50 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| ⩾50 |

2.31 |

0.80–6.67 |

0.109 |

4.01 |

1.12–14.40 |

0.021a |

|

Tumour stage | ||||||

| pT1+2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| pT3+4 |

4.38 |

1.24–15.43 |

0.012a |

5.25 |

1.45–18.99 |

0.005a |

|

Nodal status | ||||||

| N0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| Node-positive |

1.60 |

0.60–4.31 |

0.344 |

1.92 |

0.63–5.86 |

0.245 |

|

Histological grade | ||||||

| 1+2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| 3 |

0.91 |

0.26–3.21 |

0.886 |

2.62 |

0.34–20.05 |

0.335 |

|

DPYD

status | ||||||

| No CNV | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| CNV |

0.26 |

0.07–0.91 |

0.023a |

0.89 |

0.31–2.56 |

0.831 |

|

BRCA1

status | ||||||

| No CNV | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| CNV | 0.36 | 0.11–1.14 | 0.069 | 1.27 | 0.27–5.87 | 0.761 |

Abbreviations: 95% CI=95% confidence interval; CNV=copy number variation; HR=hazard ratio; OS=overall survival; TTP=time to progression.

Statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves demonstrating the effect of DPYD status on time to progression (TTP). (A) TNBC patients treated with standard 5-FU- and/or anthracycline-based chemotherapy (n=69). Somatic copy number changes (CNVs) in DPYD were significantly associated with longer TTP compared with DPYD-wildtype TNBC tissues. Five-year TTP rates for patients with aberrant DPYD and wildtype DPYD were estimated to be 90±5.5% and 65.5±8.2%, respectively. (B) TNBC subset treated with 5-FU-containing chemotherapy (n=45). Five-year TTP rates for patients with DPYD CNVs and wildtype DPYD were estimated to be 86±7.3% and 64±10.2%, respectively. (C) TNBC subset treated with radiotherapy (n=65). Five-year TTP rates for patients with DPYD CNVs and wildtype DPYD were estimated to 87.5±6.8% and 64±8.1%, respectively.

Table 4A. Multivariable analysis of risk of progression.

| Variable | HRa | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

|

DPYD status: No CNV vs CNV |

0.27 |

0.075–0.96 |

0.043b |

| Age: <50 years vs >50 years |

2.63 |

0.87–7.92 |

0.087 |

| Grading: G1+G2 vs G3 |

1.16 |

0.31–4.36 |

0.822 |

| Tumour stage: pT 1+2 vs 3+4 |

4.71 |

1.06–20.95 |

0.042b |

| Nodal status: none vs positive | 1.27 | 0.42–3.83 | 0.672 |

Abbreviations: CNV=copy number variation; HR=hazard ratio.

Total number of patients in analysis: 67; number of events: 16.

Cox proportional HR for risk of progression in patients treated with adjuvant polychemotherapy containing 5-FU and/or anthracyclines.

statistically significant

Table 4B. DPYD CNVs adjusted for BRCA1 CNVs.

| Variable | HRa | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

|

DPYD status: No CNV vs CNV |

0.37 |

0.078–1.71 |

0.201 |

| BRCA1 status: No CNV VS CNV | 0.43 | 0.133–1.37 | 0.151 |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; CNV=copy number variation; HR=hazard ratio.

Total number of patients in analysis: 57; number of events: 12.

Cox proportional HR for risk of progression in patients treated with adjuvant polychemotherapy containing 5-FU and/or anthracyclines.

The TTP was also assessed in the subgroup of all patients who had received 5-FU (n=45). In patients with DPYD CNVs, higher 5-year progression-free survival rates were observed compared with patients exhibiting normal copy numbers (86±7.3% and 64±10.2%, respectively), however, statistical significance was not reached for overall comparison (log-rank P=0.074) (Figure 3B).

In patients who had received radiotherapy (n=65), we also observed a tendency towards prolonged TTP with DPYD CNVs (log-rank P=0.056). Five-year progression-free survival rates were 87.5±6.8% in patients with DPYD CNVs compared with 64±8.1% in patients with no CNVs (Figure 3C).

Discussion

Intra-tumoural levels of DPD have been suggested to be an important prognostic factor for the efficacy of 5-FU-based chemotherapy regimens (Etienne et al, 1995; Salonga et al, 2000). For breast cancer, Horiguchi et al reported better patient outcome in case of low DPD concentrations (Horiguchi et al, 2002). Therefore, it was our intention to characterise the DPD/DPYD status in TNBC, a breast cancer subtype which is frequently treated with 5-FU-containing polychemotherapy. Here we show that DPD protein expression is profoundly downregulated (compared with normal ductal epithelium) in 64% of the TNBC specimens which is consistent with previous data obtained in other neoplastic cells (Holstege et al, 1986; Shiotani et al, 1989a, 1989b).

The mechanistic basis of DPD downregulation in cancer is largely unknown so far. Among breast cancers, the triple-negative/basal-like subtype is supposed to exhibit the greatest degree of genomic instability showing common loss of important DNA repair genes (Weigman et al, 2012). Thus, we hypothesised that this phenotype might favour recombination events including the fragile site FRA1E which disrupts the DPYD gene (Hormozian et al, 2007). Indeed, we observed for the first time a high prevalence of 41% of genomic DPYD rearrangements in TNBC tumour specimens, whereas their population incidence in the germline is extremely rare (Ticha et al, 2009; Pare et al, 2010). Secondly, our data revealed that CNVs within DPYD were positively associated with aberrant copy numbers of BRCA1. This is in line with the copy number studies by Weigman et al (2012) who suggested loss of BRCA1-dependent DNA repair might be involved in overall genomic instability in basal-like/TNBCs. Furthermore, our observations may reflect greater vulnerability of the FRA1E site in the background of BRCA1 abnormalities, as intact BRCA1 appears to be required for the stability of common fragile sites through its G2/M checkpoint function (Arlt et al, 2004).

Most of the 43 aberrations we had observed in DPYD were likely to inactivate the gene as they occurred within the coding sequence. Only six TNBCs exhibited entire gene duplications. Thus, the majority of samples with DPYD CNVs should be associated with a more or less pronounced decrease of transcript and protein levels (depending on the percentage of cells with aberrant DPYD in the tumour specimen and/or the presence of a remaining DPYD wildtype copy). Accordingly, we mainly found moderate to low DPD expression in tumour tissues with DPYD rearrangements. On the other hand, low DPD protein expression was not restricted to the presence of DPYD CNVs, but was also evident in the majority (>60%) of tumours without any aberrations. Hence, additional mechanisms for DPYD downregulation, for example, epigenetic or transcriptional regulations (Ezzeldin et al, 2005; Zhang et al, 2006) are likely to occur. Taken together, the presence of DPYD CNVs is only one parameter among others which altogether may influence DPD protein levels in TNBC.

As previous clinical and preclinical studies (Etienne et al, 1995; Salonga et al, 2000; Kobunai et al, 2007; Warnecke-Eberz et al, 2010) reported a beneficial effect of altered tumoural DPYD upon 5-FU treatment, we assessed patient outcome in the presence of DPYD CNVs. Remarkably, we observed prolonged progression-free intervals (TTP) associated with DPYD rearrangements in patients who had been treated with 5-FU- and/or anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimens. Furthermore, DPYD CNVs remained to be a strong parameter for predicting TTP independent of tumour stage. On the other hand, we could not confirm a potential benefit from DPD protein downregulation for adjuvant treatment. In contrast, our data revealed that absent/low (0–1+) DPD staining had no positive impact on TTP even in the subgroup treated with 5-FU-containing therapy only. This may be explained by our findings that, in TNBC, very low DPD expression was associated with more unfavourable clinical characteristics such as higher tumour stage (note that a large proportion of DPYD CNVs was associated with moderate DPD expression). Supporting these findings of an unfavourable clinical profile, analysis of publically available data sets of 125 hormone receptor-negative, basal-like breast cancers (supposed to be largely overlapping with TNBC), downloaded from GEO (Gyorffy et al, 2010), revealed that low DPYD mRNA expression was indeed related to shorter relapse-free survival (HR=0.37 (0.2–0.7), log-rank P=0.0016; Supplementary Figure S1).

On the basis of our results, the clinical impact of genomic DPYD rearrangements in TNBC appears to be mainly due to intrinsic tumour characteristics irrespective of the DPD expression status. Hence, DPYD CNVs may function as a surrogate marker predicting better clinical outcome upon radio- and chemotherapy. In fact, co-occurrence of BRCA1 and DPYD rearrangements, as observed in our study, may reflect a background of decreased DNA repair capacity (Weigman et al, 2012) and, thus, suggest increased vulnerability of these TNBC tumours towards DNA-damaging agents such as radiation, DNA-intercalating anthracyclines or alkylating cyclophosphamide. Also, benefit from newly developed agents, for example, PARP inhibitors (Tutt et al, 2010), targeting DNA-repair-deficient cancers, might be expected. As the prognostic value of molecular signatures of the first generation was shown to be related to ER-positive, rather than ER-negative breast cancers (Reis-Filho and Pusztai, 2011), there is still a need for prognostic or predictive factors for the TNBC subgroup. Genomic DPYD rearrangements might thus arise as a candidate marker suitable for validation in larger clinical studies.

In conclusion, we detected a high prevalence of somatic copy number aberrations in TNBCs affecting the DPYD gene. The presence of DPYD CNVs might help to subdivide TNBCs into molecular classes with better prognosis, while low DPD protein expression in general had no impact on better patient outcome. Patients with aberrant DPYD copy numbers might therefore be well suited for treatment with standard polychemotherapy combined with radiotherapy. Further studies will show whether genomic DPYD rearrangements might be incorporated into a panel of novel molecular signatures predicting clinical outcome in TNBC.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Fred Sweep, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, for his support in the generation of anti-DPD antibodies. We thank Daniela Hellmann for excellent technical assistance. This work was partly financed by Wilhelm Sander-Stiftung, Munich, Germany, contract number 2012.028.1.

R. Vijzelaar is employed by MRC-Holland b.v. which supplies the MLPA kits. All remaining authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Material

References

- Altman DG, McShane LM, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE. Reporting recommendations for Tumor Marker Prognostic Studies (REMARK): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2012;9 (5:e1001216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlt MF, Durkin SG, Ragland RL, Glover TW. Common fragile sites as targets for chromosome rearrangements. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5 (9-10:1126–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlt MF, Xu B, Durkin SG, Casper AM, Kastan MB, Glover TW. BRCA1 is required for common-fragile-site stability via its G2/M checkpoint function. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24 (15:6701–6709. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6701-6709.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubele M, Auer G, Walch AK, Munro A, Atkinson MJ, Braselmann H, Fornander T, Bartlett JM. PTK (protein tyrosine kinase)-6 and HER2 and 4, but not HER1 and 3 predict long-term survival in breast carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 2007;96 (5:801–807. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacon RD, Costanzo MV. Triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12 (Suppl 2:S3. doi: 10.1186/bcr2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colleoni M, Cole BF, Viale G, Regan MM, Price KN, Maiorano E, Mastropasqua MG, Crivellari D, Gelber RD, Goldhirsch A, Coates AS, Gusterson BA. Classical cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil chemotherapy is more effective in triple-negative, node-negative breast cancer: results from two randomized trials of adjuvant chemoendocrine therapy for node-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28 (18:2966–2973. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, Hanna WM, Kahn HK, Sawka CA, Lickley LA, Rawlinson E, Sun P, Narod SA. Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13 (15 Pt 1:4429–4434. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston CW, Ellis IO. Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer I. The value of histological grade in breast cancer: experience from a large study with long-term follow up. Histopathology. 1991;19:403–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1991.tb00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne MC, Cheradame S, Fischel JL, Formento P, Dassonville O, Renee N, Schneider M, Thyss A, Demard F, Milano G. Response to fluorouracil therapy in cancer patients: the role of tumoral dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase activity. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13 (7:1663–1670. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.7.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzeldin HH, Lee AM, Mattison LK, Diasio RB. Methylation of the DPYD promoter: an alternative mechanism for dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency in cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11 (24 Pt 1:8699–8705. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fost C, Duwe F, Hellriegel M, Schweyer S, Emons G, Grundker C. Targeted chemotherapy for triple-negative breast cancers via LHRH receptor. Oncol Rep. 2011;25 (5:1481–1487. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach J, Löffler M, Schäfer MK. Gene expression of enzymes required for the de novo synthesis and degradation of pyrimidines in rat peripheral tissues and brain. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2011;30 (12:1147–1154. doi: 10.1080/15257770.2011.603712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluz O, Liedtke C, Gottschalk N, Pusztai L, Nitz U, Harbeck N. Triple-negative breast cancer – current status and future directions. Ann Oncol. 2009;20 (12:1913–1927. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyorffy B, Lanczky A, Eklund AC, Denkert C, Budczies J, Li Q, Szallasi Z. An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123 (3:725–731. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho DH, Townsend L, Luna MA, Bodey GP. Distribution and inhibition of dihydrouracil dehydrogenase activities in human tissues using 5-luorouracil as a substrate. Anticancer Res. 1986;6 (4:781–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstege A, Pausch J, Gerok W. Effect of 5-diazouracil on the catabolism of circulating pyrimidines in rat liver and kidneys. Cancer Res. 1986;46 (11:5576–5581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hömig-Hölzel C, Savola S. Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification(MLPA) in tumor diagnostics and prognostics. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2012;21 (4:189–206. doi: 10.1097/PDM.0b013e3182595516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiguchi J, Takei H, Koibuchi Y, Iijima K, Ninomiya J, Uchida K, Ochiai R, Yoshida M, Yokoe T, Iino Y, Morishita Y. Prognostic significance of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase expression in breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002;86 (2:222–225. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hormozian F, Schmitt JG, Sagulenko E, Schwab M, Savelyeva L. FRA1E common fragile site breaks map within a 370kilobase pair region and disrupt the dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene (DPYD) Cancer Lett. 2007;246 (1-2:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janicke F, Pache L, Schmitt M, Ulm K, Thomssen C, Prechtl A, Graeff H. Both the cytosols and detergent extracts of breast cancer tissues are suited to evaluate the prognostic impact of the urokinase-type plasminogen activator and its inhibitor, plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1. Cancer Res. 1994;54 (10:2527–2530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamoshida S, Shiogama K, Shimomura R, Inada K, Sakurai Y, Ochiai M, Matuoka H, Maeda K, Tsutsumi Y. Immunohistochemical demonstration of fluoropyrimidine-metabolizing enzymes in various types of cancer. Oncol Rep. 2005;14 (5:1223–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SP, Martel M, Harris LN. Triple negative breast cancer: current understanding of biology and treatment options. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;20 (1:40–46. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3282f40de9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobunai T, Ooyama A, Sasaki S, Wierzba K, Takechi T, Fukushima M, Watanabe T, Nagawa H. Changes to the dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene copy number influence the susceptibility of cancers to 5-FU-based drugs: data mining of the NCI-DTP data sets and validation with human tumour xenografts. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43 (4:791–798. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke C, Mazouni C, Hess KR, Andre F, Tordai A, Mejia JA, Symmans WF, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Hennessy B, Green M, Cristofanilli M, Hortobagyi GN, Pusztai L. Response to neoadjuvant therapy and long-term survival in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26 (8:1275–1281. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linn SC, Van 't Veer LJ. Clinical relevance of the triple-negative breast cancer concept: genetic basis and clinical utility of the concept. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45 (Suppl 1:11–26. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(09)70012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Zhang R, Diasio RB. Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase activity in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and liver: population characteristics, newly identified deficient patients, and clinical implication in 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 1993;53 (22:5433–5438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE, Gion M, Clark GM. Statistics Subcommittee of NCI-EORTC Working Group on Cancer Diagnostics. Reporting recommendations for tumor MARKer prognostic studies (REMARK) Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;100 (2:229–235. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta PP, Whalen P, Baxi SM, Kung PP, Yamazaki S, Yin MJ. Effective targeting of triple-negative breast cancer cells by PF-4942847, a novel oral inhibitor of Hsp 90. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17 (16:5432–5442. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pare L, Paez D, Salazar J, Del RE, Tizzano E, Marcuello E, Baiget M. Absence of large intragenic rearrangements in the DPYD gene in a large cohort of colorectal cancer patients treated with 5-FU-based chemotherapy. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70 (2:268–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03683.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punsawad C, Maneerat Y, Chaisri U, Nantavisai K, Viriyavejakul P. Nuclear factor kappa B modulates apoptosis in the brain endothelial cells and intravascular leukocytes of fatal cerebral malaria. Malar J. 2013;12:260. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis-Filho JS, Pusztai L. Gene expression profiling in breast cancer: classification, prognostication, and prediction. Lancet. 2011;378 (9805:1812–1823. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61539-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis-Filho JS, Tutt AN. Triple negative tumours: a critical review. Histopathology. 2008;52 (1:108–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez AA, Makris A, Wu MF, Rimawi M, Froehlich A, Dave B, Hilsenbeck SG, Chamness GC, Lewis MT, Dobrolecki LE, Jain D, Sahoo S, Osborne CK, Chang JC. DNA repair signature is associated with anthracycline response in triple negative breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123 (1:189–196. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0983-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salonga D, Danenberg KD, Johnson M, Metzger R, Groshen S, Tsao-Wei DD, Lenz HJ, Leichman CG, Leichman L, Diasio RB, Danenberg PV. Colorectal tumors responding to 5-fluorouracil have low gene expression levels of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, thymidylate synthase, and thymidine phosphorylase. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6 (4:1322–1327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saville DJ. Multiple comparison procedures: the practical solution. Am Statist. 1990;44:174–180. [Google Scholar]

- Schouten JP, McElgunn CJ, Waaijer R, Zwijnenburg D, Diepvens F, Pals G. Relative quantification of 40 nucleic acid sequences by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30 (12:e57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnf056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz M, Zlotorynski E, Kerem B. The molecular basis of common and rare fragile sites. Cancer Lett. 2006;232 (1:13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiotani T, Hashimoto Y, Fujita J, Yamauchi N, Yamaji Y, Futami H, Bungo M, Nakamura H, Tanaka T, Irino S. Reversal of enzymic phenotype of thymidine metabolism in induced differentiation of U-937 cells. Cancer Res. 1989a;49 (23:6758–6763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiotani T, Hashimoto Y, Tanaka T, Irino S. Behavior of activities of thymidine metabolizing enzymes in human leukemia-lymphoma cells. Cancer Res. 1989b;49 (5:1090–1094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ticha I, Kleiblova P, Fidlerova J, Novotny J, Pohlreich P, Kleibl Z. Lack of large intragenic rearrangements in dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPYD) gene in fluoropyrimidine-treated patients with high-grade toxicity. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;64 (3:615–618. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-0970-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner NC, Reis-Filho JS. Basal-like breast cancer and the BRCA1 phenotype. Oncogene. 2006;25 (43:5846–5853. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner NC, Reis-Filho JS, Russell AM, Springall RJ, Ryder K, Steele D, Savage K, Gillett CE, Schmitt FC, Ashworth A, Tutt AN. BRCA1 dysfunction in sporadic basal-like breast cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26 (14:2126–2132. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tutt A, Robson M, Garber JE, Domchek SM, Audeh MW, Weitzel JN, Friedlander M, Arun B, Loman N, Schmutzler RK, Wardley A, Mitchell G, Earl H, Wickens M, Carmichael J. Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and advanced breast cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;376 (9737:235–244. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60892-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kuilenburg AB, Meijer J, Mul AN, Hennekam RC, Hoovers JM, de Die-Smulders CE, Weber P, Mori AC, Bierau J, Fowler B, Macke K, Sass JO, Meinsma R, Hennermann JB, Miny P, Zoetekouw L, Vijzelaar R, Nicolai J, Ylstra B, Rubio-Gozalbo ME. Analysis of severely affected patients with dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency reveals large intragenic rearrangements of DPYD and a de novo interstitial deletion del(1)(p13.3p21.3) Hum Genet. 2009;125 (5-6:581–590. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0653-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kuilenburg AB, Meijer J, Mul AN, Meinsma R, Schmid V, Dobritzsch D, Hennekam RC, Mannens MM, Kiechle M, Etienne-Grimaldi MC, Klumpen HJ, Maring JG, Derleyn VA, Maartense E, Milano G, Vijzelaar R, Gross E. Intragenic deletions and a deep intronic mutation affecting pre-mRNA splicing in the dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene as novel mechanisms causing 5-fluorouracil toxicity. Hum Genet. 2010;128 (5:529–538. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0879-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Shi Y, Yuan Z, Wang X, Liu D, Peng R, Teng X, Qin T, Peng J, Lin G, Jiang X. Classical CMF regimen as adjuvant chemotherapy for triple-negative breast cancer may be more effective compared with anthracycline or taxane-based regimens. Med Oncol. 2011;29 (2:547–553. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-9964-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnecke-Eberz U, Metzger R, Bollschweiler E, Baldus SE, Mueller RP, Dienes HP, Hoelscher AH, Schneider PM. TaqMan low-density arrays and analysis by artificial neuronal networks predict response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation in esophageal cancer. Pharmacogenomics. 2010;11 (1:55–64. doi: 10.2217/pgs.09.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigman VJ, Chao HH, Shabalin AA, He X, Parker JS, Nordgard SH, Grushko T, Huo D, Nwachukwu C, Nobel A, Kristensen VN, Borresen-Dale AL, Olopade OI, Perou CM. Basal-like Breast cancer DNA copy number losses identify genes involved in genomic instability, response to therapy, and patient survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133 (3:865–880. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1846-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Li L, Fourie J, Davie JR, Guarcello V, Diasio RB. The role of Sp1 and Sp3 in the constitutive DPYD gene expression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1759 (5:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.