Abstract

The relevance of parenting behavior to toddlers’ development necessitates a better understanding of the influences on parents during parent-child interactions. Toddlers’ inhibited temperament may relate to parenting behaviors, such as intrusiveness, that predict outcomes later in childhood. The conditions under which inhibited temperament relates to intrusiveness, however, remain understudied. A multi-method approach would acknowledge that several levels of processes determine mothers’ experiences during situations in which they witness their toddlers interacting with novelty. As such, the current study examined maternal cortisol reactivity and embarrassment about shyness as moderators of the relation between toddlers’ inhibited temperament and maternal intrusive behavior. Participants included 92 24-month-olds toddlers and their mothers. Toddlers’ inhibited temperament and maternal intrusiveness were measured observationally in the laboratory. Mothers supplied saliva samples at the beginning of the laboratory visit and 20 minutes after observation. Maternal cortisol reactivity interacted with inhibited temperament in relation to intrusive behavior, such that mothers with higher levels of cortisol reactivity were observed to be more intrusive with more highly inhibited toddlers. Embarrassment related to intrusive behavior as a main effect. These results highlight the importance of considering child characteristics and psychobiological processes in relation to parenting behavior.

Keywords: parenting, temperament, cortisol, HPA, toddlers

Parent-child interactions represent a critical context for risk for social withdrawal and anxiety problems for toddlers exhibiting inhibited temperament (Rubin, Coplan, & Bowker, 2009). Some mothers behave intrusively during interactions with novelty, which heightens toddlers’ risk for negative outcomes (Nachmias, Gunnar, Mangelsdorf, Parritz, & Buss, 1996; Rubin et al., 2009). We know little about the factors that may determine which mothers respond intrusively, but maternal emotion reactivity may play a role. Cortisol reactivity is a well-documented psychobiological indicator of the stress response that, with few exceptions (e.g., Martorell & Bugental, 2006; Seltzer et al., 2009; Sethre-Hofstad, Stansbury, & Rice, 2002; Thompson & Trevathan, 2008) has rarely been studied in the context of parenting. Understanding the multiple systems involved in maternal reactions to parenting situations may elucidate parent-child interactions that ultimately affect children’s adjustment outcomes. To this end, we examined maternal cortisol reactivity over the course of toddlers’ interactions with novelty, as well as mothers’ subjective reactivity (i.e., embarrassment) to toddlers’ displays of shyness, as moderating the relation between inhibited temperament and maternal intrusiveness.

Inhibited Temperament and Intrusive Parenting

Inhibited temperament (also described as behavioral inhibition) characterizes wary, hesitant, and avoidant responses to novelty (Kagan, Reznick, Clark, Snidman, & Garcia-Coll, 1984) and predicts negative anxiety-spectrum outcomes (Rubin et al., 2009). Given that this association is often moderate in strength, research has focused on factors that increase the likelihood that temperamentally inhibited toddlers display maladjustment.

Not surprisingly, much of this research has focused on the caregiving environment. A number of empirical studies have demonstrated that intrusive maternal behavior, characterized by the unsolicited assistance with a novel task or pushing toddlers towards novelty, occurs frequently with inhibited toddlers and predicts heightened risk for maladjustment (Nachmias et al., 1996; Rubin et al., 2009). Unfortunately, intrusive parenting prevents the development of children’s independent regulation (Rubin et al., 2009).

Not all mothers of inhibited toddlers display intrusiveness, suggesting the presence of moderators. Very little research has considered mothers’ experiences when engaging with their toddlers in situations that might elicit wariness and the effect this can have on parent-child interactions. There has been suggestion, however, that mothers’ attempts to change their toddlers’ behavior are linked to distress (Kagan et al., 1984). Indeed, some mothers have reported finding it stressful to have an inhibited child, and these mothers were more likely to try to change (perhaps in an intrusive manner) inhibited tendencies in their children (Kagan et al., 1984). This may occur in Western culture because an inhibited style is inconsistent with values of autonomy and assertiveness (Rubin et al., 2009). The role of maternal emotion reactivity in the relation between inhibited temperament and intrusive parenting has not been examined specifically. Generally, stress hinders parents’ abilities to use sensitive, effective strategies with children to promote positive development (Crnic & Low, 2002), warranting investigation of reactivity in this specific context.

Maternal Reactivity to Children’s Interactions with Novelty

Psychobiological stress reactivity remains particularly neglected in this area of inquiry. One such index of stress is the production of cortisol by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) system. Psychosocial stress activates the HPA, and, at the end of a cascade of biological reactions, the stress hormone, cortisol, is produced (Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007). Reactivity of cortisol occurs approximately 20 minutes after the stressor, with recovery occurring 40 minutes post-stressor. In children and adults, individual differences in HPA/cortisol reactivity relate to behavior in a variety of stressful situations (Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007). In previous studies, increased maternal cortisol reactivity, considered to be in response to the “state” rather than an index of a fixed “trait” (Adam, 2012), related to difficult child temperament and mothers’ harsh parenting (Martorell & Bugental, 2006). Decreased cortisol reactivity has been shown to relate to increased maternal sensitivity (Thompson & Trevathan, 2008). Mothers’ HPA reactivity in relation to intrusiveness and toddlers’ inhibited temperament remains understudied.

Examining mothers’ cortisol reactivity alongside their subjective reactivity to toddlers’ inhibited behavior would elucidate the relative importance of these multi-systemic predictors of parenting behavior. It is reasonable to believe that these mothers’ perceived negative reactions to their toddlers’ inhibition provide a context for their parenting. Dix (1993) proposed that negative affect induced by children’s non-optimal behavior instigates power-assertive parenting, of which intrusiveness may be an example. Several studies have found an association between anger and more assertive/intrusive parenting (Grusec, Dix, & Mills, 1982; Mills & Rubin, 1990). Another, less frequently studied emotional response that may be particularly important for children’s shyness is that of embarrassment. Embarrassment is a moderately common response to shyness, indicating room for individual differences, that has previously been associated with non-optimal parenting such as using an authoritarian style (Coplan, Hastings, Lagacé-Séguin, & Moulton, 2002). Coplan and colleagues (2002) suggested that embarrassment may prompt parents to exert control to terminate undesired child behavior. We suggest that it provides the context in which parenting relates to temperament. For mothers more prone to embarrassment, having an inhibited toddler might prompt a pattern of intrusive control in situations that highlight temperamental biases. Whether embarrassment moderates the relation between inhibited temperament and intrusive behavior has yet to be determined.

To add to the growing literature concerning determinants of parent behavior, we examined whether maternal cortisol reactivity and embarrassment moderated the relation between toddlers’ inhibited temperament and intrusive maternal behavior in a laboratory-based study. A multi-method assessment of reactivity was deemed important because, although self-report measures may only capture the subjective component of emotional responding, be susceptible to social desirability, and rely on one’s ability to accurately assess internal experiences (Rosenthal, Gratz, Kossen, Cheavans, Lejuez, & Lynch, 2008), they have sometimes been found to relate more closely to behavior than biological measures (Mauss, Wilhelm, & Gross, 2004). We therefore hypothesized that both cortisol reactivity and embarrassment would uniquely moderate the association between inhibited temperament and maternal intrusiveness.

Method

Participants

Participants included 117 mothers and toddlers, recruited via mail from birth announcements and in-person at meetings of the Women, Infants, and Children program. One mother refused saliva collection. Saliva samples from 96 (82%) of the remaining mothers yielded interpretable cortisol values. We excluded four mothers who were in their last trimester of pregnancy. The final sample of 92 mothers (aged 20.29 – 46.09 years, Mage = 33.73 years) and toddlers (40 female; aged 23.97 – 27.00 months, Mage = 24.71 months) represented the range of socioeconomic status and reported, on average, being middle class (Table 1). Mothers/toddlers were 87%/79% European American, 3%/9% African American, 5%/8% Asian American, 1%/1% American Indian, 0%/2% biracial, and 2%/1% “other.” One mother (1%) and 6 toddlers (6%) were described as being of Hispanic/Latino origin.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Variables

| Variable | Mean | SD | Range | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SES (Hollingshead Index)a | 49.02 | 12.50 | 17.00 – 66.00 | −.18† | −.18† | −.13 | −.01 |

| 2. Maternal intrusivenessa | 0.00 | 0.95 | −0.82 – 2.84 | -- | .11 | .29** | .03 |

| 3. Maternal cortisol reactivitya | 0.00 | 1.54 | −4.23 – 7.25 | -- | .27* | .05 | |

| 4. Maternal embarrassmentb | 1.39 | 0.74 | 1.00 – 5.00 | -- | −.09 | ||

| 5. Toddler inhibited temperamenta | 0.01 | 0.83 | −1.02 – 2.76 | -- |

Note. Maternal intrusiveness and toddler inhibited temperament are composites of standardized variables (Z-scores). Maternal cortisol reactivity represents the raw residuals from a regression in which post-visit cortisol values were regressed on pre- visit values, time of day, and maternal asthma medication status. Descriptive statistics report the raw values of maternal embarrassment; correlations use the square root transformed variable.

n = 92,

n = 80.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01.

Procedure

Mothers and their toddlers participated in a laboratory visit, and mothers completed questionnaires assessing demographic information and subjective responses to their toddlers’ displays of shyness. At the laboratory, toddlers’ inhibited temperament was observed from a Risk Room paradigm. The experimenter led the toddler and mother to a room containing “risk-taking” objects (i.e., tunnel, balance beam, trampoline, black box with opening, and an angry-looking gorilla mask on a pedestal). The experimenter instructed the mother to remain neutral in her behavior and the toddler to play in the room “however you like.” After 3 minutes, the experimenter returned and provided up to three prompts for the toddler to engage with each of the activities in a set order.

Then, mothers and toddlers engaged in a number of novelty tasks (Stranger Approach, Robot, Clown, Puppet Show, and Spider episodes; see Buss, 2011 and Kiel & Buss, 2012, for full episode descriptions). Mothers’ intrusive behavior was observed during the last episode, “Spider” which tends to elicits high levels of distress compared to other novelty tasks (Buss, 2011; Kiel & Buss, 2012) and so was considered to elicit the peak maternal stress response. The experimenter asked the mother to have her toddler seated on her lap in a chair in the corner of the room. In the opposite corner was a large stuffed-animal spider, attached to a hidden, remote controlled truck. Both the mother and the toddler were instructed to act naturally and interact “however you typically would.” After the experimenter left the room, the spider, controlled by remote from behind a one-way mirror, approached and withdrew from the toddler twice with 10-s pauses between each movement. The experimenter then returned to the room and asked the toddler to touch the spider with up to three prompts. Episodes occurred in the same order for all participants. A previous study (Kiel & Buss, 2010) using counterbalanced episodes found no order effects for maternal intrusive behavior. The laboratory visit lasted 1.5 hours.

Saliva samples were taken from mothers after a brief acclimation to the laboratory but before any tasks occurred (“pre-visit”), and again at the end of the visit (“post-visit”), 20 minutes after the Spider episode (with neutral activities in between) to account for time required for cortisol to peak post-stressor. Mothers were also asked to take supplies with them, provide another sample after arriving home or at their next destination (“home”), and return it to the lab in a pre-addressed and stamped envelope. The home sample was only used in the imputation of missing pre-visit and post-visit cortisol values.

For each saliva collection, mothers were asked to place one end of the cotton role that came with the Salivette tube (Sartstedt, NC) in their mouths until it was saturated with saliva. The roll was then placed back in the Salivette and sealed. All tubes were frozen at −50° until they were shipped on dry ice to Biochemisches Labor in Trier, Germany, where they were stored at −20°C until assayed for cortisol. Samples were centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 minutes and assayed using a competitive solid phase time-resolved fluorescence immunoassay with flouromeric end point detection (DELFIA). The test used 100 μl of saliva, and all samples were analyzed in duplicate. Testing had a range of sensitivity from 0.30–100 nmol/l. Average intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation ranged from 4.0–6.7% and 7.1–9.0% respectively.

Measures

Toddler inhibited temperament

The inhibited temperament composite comprised behaviors scored from the Risk Room that have previously shown adequate reliability, significant inter-correlations and, as a composite, relations to inhibition-related outcomes (Kiel & Buss, 2010). Reliability between coders and a master coder was computed on 15–20% of cases (on an epoch-by-epoch basis when appropriate) and is noted in parentheses. Latency to touch the first toy (% agreement = .90, Pearson r = .99) was measured as the number of seconds between the experimenter leaving the room and the toddler’s first intentional contact with one of the objects. Attempt to be held (% agreement = .94, intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] = .88), approach towards parent (% agreement = .73, ICC = .85), and tentativeness of play (% agreement = .83, ICC = .78) were scored on 0 (none) to 3 (extreme) scales in each 10-second epoch of the episode, and the average of scores was computed across epochs. Finally, compliance to experimenter (Cohen’s kappa = .75) was the count (0 to 5) of activities with which the toddler engaged when prompted by the experimenter. The mean of these scores (after reversing compliance to experimenter and standardizing all variables) was taken to form the composite (α = .84), with higher values indicating more extreme inhibited temperament.

Maternal intrusive behavior

Using a coding scheme previously established with adequate inter-rater reliability by Kiel and Buss (2010), the Spider episode was divided into 10-s epochs, and mothers were scored for their peak intensity of intrusive behavior (0 = no display, 1 = leaning child towards the spider, 2 = one brief push or carrying of child towards the spider, 3 = forceful push, carrying child into close proximity, or forcing physical contact with the spider) within each epoch. Reliability computed between coders and a master coder was good (ICC = .93). The average of scores across the epochs of the episode and the single-value maximum score for the entire episode were computed. These values were standardized and given Z-scores. The mean of these scores (r[90] = .79, p < .001) comprised the measure of intrusiveness.

Maternal subjective reactivity to toddler interactions with novelty

Mothers completed the Child Behavior Vignettes (Hastings & Coplan, 1999), which asks mothers to read hypothetical vignettes and imagine their children displaying various behaviors. The current study focuses on the Shyness vignette, which depicts the mother seeing her child looking nervous and refraining from playing while watching unfamiliar children play. Mothers then rated the extent to which they would feel embarrassed by their toddlers’ behavior on a 1 (not at all) to 5 (very strongly) scale. Certainly, results should be interpreted in the context of the 1-item nature of this measure; however, its validity has previously been demonstrated through its meaningful relation to parenting styles and beliefs (Coplan et al., 2002).

Results

Cortisol Data Transformation and Imputation

Of the 92 mothers, 70 (76%) had pre-visit, 67 (73%) had post-visit, and 58 (63%) had home samples of cortisol. Cortisol values below the minimum sensitivity of the assay (.30) were assigned that value, and outliers (beyond 3 SD above the mean) were truncated to the next highest value within +3 SD. Pre- and post-visit cortisol variables demonstrated reasonable normality (skew < 2.00). Time of the laboratory visit was related to both pre-visit (r[68] = −.49, p < .01) and post-visit cortisol values (r[65] = −.32, p < .01), and pre-visit values differed depending on whether mothers (n = 2) currently took asthma medication (t[68] = −2.34, p < .05). Cortisol values did not differ depending on mothers’ use of birth control (n = 16), antidepressants (n = 5), or other medication (n = 19).

Before a measure of reactivity was computed, missing values of cortisol assays were imputed using multiple imputation. Using guidelines in the literature (Graham, 2009), the imputation used all available values of pre-visit, post-visit, and home cortisol, time of day of the visit, and a dummy variable indicating asthma medication. Values across 10 imputations were pooled to create final measures of pre-visit and post-visit cortisol.

Reactivity was computed by regressing post-visit cortisol values on pre-visit cortisol values, time of visit, and asthma medication status and ascertaining residualized scores. More positive values indicate that post-visit scores were higher than expected given the other variables and thus reflect more reactivity. Thus, these residualized scores comprised the variable of maternal cortisol reactivity. This final variable did not differ in value for mothers with both samples versus mothers who required imputation of missing values.

Preliminary Statistics

Descriptive statistics and bivariate relations are presented in Table 1. Slight skew in mothers’ self-reported embarrassment necessitated a square root transformation. No gender differences existed for any variables (all ps > .10). Our two measures of reactivity, cortisol reactivity and embarrassment by shyness, were modestly but significantly related; thus, mothers’ biological reactivity to their toddlers’ interactions with novelty related to their embarrassment by shy behavior. Embarrassment also related to maternal intrusive behavior. SES marginally related to maternal intrusive behavior, so it was considered a covariate in subsequent analyses.

Regression Analyses

A multiple regression analysis examined whether mothers’ cortisol reactivity and embarrassment moderated the relation between toddlers’ inhibited temperament and observed maternal intrusiveness. All variables were centered at their means prior to analyses. Significant interactions were probed by examining the simple slopes of the relation between inhibited temperament and intrusiveness at standard values (−1 SD [low], mean, +1 SD [high]) of the relevant reactivity variable.

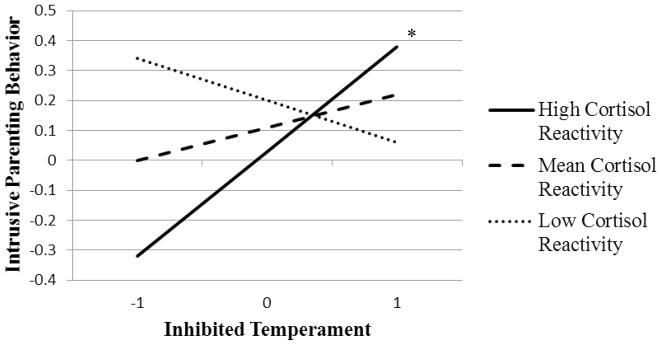

In a multiple regression model, maternal intrusive behavior was regressed on SES, inhibited temperament, maternal cortisol reactivity, maternal embarrassment by shyness, inhibited temperament × cortisol reactivity, and inhibited temperament × embarrassment (Table 2). Within this model, the inhibited temperament × cortisol reactivity interaction reached significance. Probing simple slopes revealed that inhibited temperament did not relate to intrusive maternal behavior at low (β = −0.13, t[73] = −0.84, p = .40) or mean maternal cortisol reactivity (β = 0.10, t[73] = 0.89, p = .38), but the relation was significant at high cortisol reactivity (β = .32, t[73] = 2.32, p < .05) (Figure 1). In other words, mothers displayed more intrusive behavior when their toddlers displayed increased inhibited temperament, but only if mothers also experienced more extreme cortisol reactivity.

Table 2.

Multiple regression predicting maternal intrusive behavior

| Predictor | b | SE | β | t-test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic status | −0.003 | 0.008 | −0.04 | −0.39 |

| Fearful temperament | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.89 |

| Maternal cortisol reactivity | −0.06 | 0.07 | −0.10 | −0.85 |

| Maternal embarrassment | 1.03 | 0.42 | 0.31 | 2.45* |

| Inhibited temperament × Cortisol reactivity | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.29 | 2.33* |

| Inhibited temperament × Embarrassment | 0.19 | 0.57 | 0.04 | 0.33 |

Note. All variables were centered at their means prior to analysis and entered simultaneously. The model was significant (R2 = .18, 95% CI [.04, .32], F[6, 73] = 2.71, p < .05).

p < .05.

Figure 1.

Inhibited temperament interacted with maternal cortisol reactivity to predict maternal intrusive behavior. Inhibited temperament relates to intrusive behavior at high, but not low or mean, values of maternal cortisol reactivity.

*p < .05.

Also within this model, mothers’ embarrassment by their toddlers’ shyness related to increased intrusiveness as it did at the bivariate level. Above and beyond the other variables, mothers who reported being embarrassed by their toddlers’ shyness tended to be more intrusive. The non-significant embarrassment × inhibited temperament interaction indicated that this did not depend on toddlers’ temperaments.

Discussion

Understanding the complexity of parent-child interactions requires examinations of both child and parent contributions to parenting. In this vein, the current study sought evidence for psychobiological and subjective factors that moderated the extent to which toddlers’ inhibited temperament related to intrusive parenting behavior. These results augment our understanding of how toddlers come to develop along different developmental pathways and inform appropriate intervention efforts that acknowledge the complex nature of maternal responses to toddler behavior. The current study examined mothers’ biological and subjective reactivity as potential moderators of the association between inhibited temperament and intrusive parenting.

Maternal cortisol reactivity, measured over the course of toddlers’ interactions with novelty, moderated the relation between inhibited temperament and intrusive behavior. As mothers displayed higher reactivity of their HPA system via cortisol production, having a more inhibited toddler related to being more intrusive during the novelty tasks. These results suggest that when the mother of an inhibited toddler has a biological stress response to watching the child participate in novel situations, she may be prompted to do something about it, such as force behavior that goes against her toddler’s nature (e.g., push the toddler towards novelty, force interaction). Because maternal cortisol reactivity and toddler temperament were measured contemporaneously, we cannot determine whether this stress response develops over time in some mothers of temperamentally inhibited toddlers, or whether these features always existed for each individual. For example, it could be that maternal intrusiveness is more likely to occur when mothers and toddlers share a propensity towards distress to novelty, displayed in toddlers as inhibited temperament and in mothers as cortisol reactivity. Given a substantial portion of variance due to genetics in both inhibited temperament (Robinson, Kagan, Reznick, & Corley, 1992) and cortisol levels (Bartles, Van den Berg, Sluyter, Boomsma, & de Geus, 2003), it is possible that heritability accounts for some of the relations found among temperament, parenting, and cortisol. It is also possible that a pattern of intrusive parenting predated and exacerbated toddler inhibition. Future research should determine the sequence of the development of these characteristics to more clearly identify how and when intrusive parenting occurs as a result.

We also found that mothers displayed more intrusive behavior when they reported being embarrassed by their toddlers’ displays of shyness. This relation, however, did not depend on toddler temperament. This is consistent with previous studies finding a relation between embarrassment and non-optimal parenting (Coplan et al., 2002). When parents are embarrassed by shy, inhibited behavior, they may desire to resolve the situation quickly and therefore exert control over it. Perhaps these mothers believe that if their toddlers are forced to interact with the feared stimulus, they will “get over” their inhibition. This study cannot speak to the cognitions that may play a role in the association between embarrassment and intrusive behavior, so further study into the mechanisms connecting embarrassment to intrusiveness are warranted. Interestingly, this finding emerged despite the measuring embarrassment for a social context and intrusiveness in a non-social situation. Whether these relations strengthen (or embarrassment then does act as a moderator) within the same domain (e.g., both in a social context) cannot be concluded and warrants continued attention. Further, this conceptualization is relevant for high levels of intrusiveness that predict negative outcomes for inhibited toddlers. Gentle encouragement and sensitive systematic desensitization may be quite adaptive for these toddlers; we do not propose that the current results contradict these efforts.

Some not yet mentioned limitations of the current study should be considered. The correlational nature of the study precludes conclusions about causal relations among variables. Maternal variables in non-novel contexts were not presently measured; contrasting the current results to those found in contexts that do not highlight inhibition would speak to the domain-specificity of our findings. Finally, the sample (which was somewhat small) from which these data were derived comprised mostly middle-class, European American families and included mothers exclusively. The generalizability of these findings to fathers and to parents from different sociocultural groups may be limited and should be examined in future work.

Overall, results of the current study support the relevance of psychobiological processes to intrusive parenting for more inhibited toddlers, above and beyond mothers’ subjective responses to toddlers’ shy, inhibited behavior. These findings augment a biopsychosocial model of parenting, suggesting that HPA stress reactivity has important implications for the parenting of inhibited toddlers.

Acknowledgments

The project from which these data were derived was supported, in part, by a National Research Service Award from the National Institute of Mental Health (F31 MH077385-01) and a University of Missouri Department of Psychology Sciences Dissertation Grant granted to the first author, and a grant to Kristin Buss from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH075750). We express our appreciation to the families and toddlers who participated in this project.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth J. Kiel, Miami University

Kristin A. Buss, The Pennsylvania State University

References

- Adam E. Emotion-cortisol transactions occur over multiple time scales in development: Implications for research on emotion and the development of emotional disorders. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2012;77(2):7–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2012.00657.x. Serial no.303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartles M, Van den Berg M, Sluyter F, Boomsma DI, de Gues EJC. Heritability of cortisol levels: Review and simultaneous analysis of twin studies. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28:121–137. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(02)00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA. Which fearful toddlers should we worry about? Context, fear regulation, and anxiety risk. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:804–819. doi: 10.1037/a0023227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Hastings PD, Lagacé-Séguin DG, Moulton CE. Authoritative and authoritarian mothers’ parenting goals, attributions, and emotions across different childrearing contexts. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2002;2:1–26. doi: 10.1207/S15327922PAR0201_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crnic K, Low C. Everyday stresses and parenting. In: Bornstein M, editor. Handbook of parenting: Practical issues in parenting. 2. Vol. 5. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 243–267. [Google Scholar]

- Dix T. Attributing dispositions to children: An interactional analysis of attribution in socialization. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1993;19:633–643. doi: 10.1177/0146167293195014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grusec J, Dix T, Mills R. The effect of type, severity, and victim of children’s transgressions on maternal discipline. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Sciences. 1982;14:276–289. doi: 10.1037/h0081271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Quevedo K. The neurobiology of stress and development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, Coplan R. Conceptual and empirical links between children’s social spheres: Relating maternal beliefs and preschoolers’ behaviors with peers. In: Piotrowski CC, Hastings PD, editors. New directions for child and adolescent development. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1999. pp. 43–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS, Clarke C, Snidman N, Garcia-Coll C. Behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar. Child Development. 1984;55:2212–2225. doi: 10.2307/1129793. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, Buss KA. Maternal accuracy and behavior in anticipating children’s responses to novelty: Relations to fearful temperament and implications for anxiety development. Social Development. 2010;19:304–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00538.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, Buss KA. Associations among toddler fearful temperament, context-specific maternal protective behavior, and maternal accuracy. Social Development. 2012;21:742–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00645.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martorell GA, Bugental DB. Maternal variations in stress reactivity: Implications for harsh parenting practices with very young children. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:641–647. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauss IB, Wilhelm FH, Gross JJ. Is there less to social anxiety than meets the eye? Emotion experience, expression, and bodily responding. Cognition and Emotion. 2004;18:631–662. doi: 10.1080/02699930341000112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mills RSL, Rubin KH. Parental beliefs about problematic social behaviors in early childhood. Child Development. 1990;61:138–151. doi: 10.2307/1131054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nachmias M, Gunnar M, Mangelsdorf S, Parritz RH, Buss KA. Behavioral inhibition and stress reactivity: The moderating role of attachment security. Child Development. 1996;67:508–522. doi: 10.2307/1131829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JL, Kagan J, Reznick JS, Corley R. The heritability of inhibited and uninhibited behavior: A twin study. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:1030–1037. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.28.6.1030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal MZ, Gratz KL, Kossen DS, Cheavens JS, Lujuez CW, Lynch TR. Borderline personality disorder and emotional responding: A review of the research literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:75–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Coplan RJ, Bowker JC. Social withdrawal in childhood. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:141–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Almeida DM, Greenberg JS, Savla J, Stawski RS, Hong J, Taylor JL. Psychological and biological markers of daily lives of midlife parents of children with disabilities. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2009;50:1–15. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethre-Hofstad L, Stansbury K, Rice MA. Attunement of maternal and child adrenocortical response to child challenge. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27:731–747. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(01)00077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson LA, Trevathan WR. Cortisol reactivity, maternal sensitivity, and learning in 3-month-old infants. Infant Behavior and Development. 2008;31:92–106. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]