Abstract

Fine scale genomic regulation is critical for maintaining genomic integrity and is often disrupted in neurodevelopmental disorders. An intriguing new study reveals the intricate biochemical complexity of de novo post-translational modifications of MeCP2, including activity-dependent protein-protein interactions that 'bridge' the nuclear receptor co-repressor (NCoR) complex to chromatin and lead to alterations in gene expression that characterize Rett syndrome.

Gene regulatory programs controlling cellular phenotype are expressed through transcription and translation, which can be dynamically modified by activity-dependent and epigenetic processes. Since its discovery in 1992 and established link with Rett syndrome (RTT) in 1999, methyl-CpG binding protein (MeCP2) and its role in RTT has been studied in great detail1,2. MeCP2 is an abundantly expressed, highly conserved, basic nuclear protein, present in both neurons and glia, and is thought to be both a transcriptional activator and repressor controlling the global epigenetic landscape3. RTT, caused by mutations in MeCP2, is a monogenic, X-linked, neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by mild-to-severe cognitive impairments, motor coordination deficits and epileptic seizures1. Cell type- and region-specific transgenic knockout mouse models with disrupted MeCP2 have been generated to study cellular and synaptic defects of RTT, model behavioral phenotypes and understand molecular signals involved in disease initiation, progression and maintenance. Still, fundamental questions about the mechanisms by which the genome-wide distribution of MeCP2 influences the chromatin landscape4, and how MeCP2 functions as a node for the molecular convergence of activity-dependent neuronal signals, remain unresolved. A new study5 has now revealed one precise mechanism by which MeCP2 controls activity-dependent gene transcription, in a manner that can explain some of the diverse molecular and physiological effects of RTT6.

To search for activity-dependent signatures of MeCP2 activation, the authors first mapped sites in MeCP2 using phosphotryptic-mapping techniques. This involved culturing E16 mouse cortical neurons in the presence of P32 orthophosphate, followed by treatment with extracellular K+, via KCl application, to trigger membrane depolarization. Cell lysate was then prepared, incubated with anti-MeCP2 antibody and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Trypsin-digested phospho-peptides were separated using 2D-electrophoresis and mapped with autoradiography. To validate these observations, the authors used an in vivo kainic acid-mediated seizure generation model. Furthermore, differential activation of these phosphorylated sites was achieved with distinct afferent stimuli (KCl, BDNF or forskolin). Overall, these studies revealed four new sites of MeCP2 (S86, S274, T308 and S421) that are robustly phosphorylated by neuronal activity, albeit in a stimulus-selective manner.

Molecular genetic testing and sequence analysis has revealed that most RTT mutations arise de novo. One common RTT missense mutation R306C, proximal to the T308 phosphorylation site, is particularly interesting as this mutation disrupts MeCP2's interaction with the nuclear receptor co-repressor (NCoR/SMRT) complex, as reported in a recent study7. This interaction is required for histone deacetylation-mediated gene repression. T308, once phosphorylated in an activity-dependent manner, similarly alters the MeCP2-NCoR-HDAC interaction, thereby suppressing the ability of MeCP2 to repress transcription. This was evident from a luciferase reporter assay, but to further demonstrate the relationship, the authors generated T308A knock-in mice. These mice only lack activity-dependent MeCP2 T308 phosphorylation. T308A mice showed normal levels of depolarization-induced expression of most immediate-early genes (Arc, Fos, Nptx2 and Adcyap1). However, mRNA levels of two genes, Npas4, which plays an important role in inhibitory synaptic maturation and plasticity8,9, and Bdnf, which is activated by Npas4, were reduced in T308A knock-in neurons compared to wild-type controls. Prolonged dark-rearing of adult mice followed by 6 h of light exposure also demonstrated attenuation of Npas4 and Bdnf induction in visual cortex. To link the RTT missense mutation R306C with nearby T308 activity-dependent phosphorylation, R306C knock-in mice were exposed to kainic acid and the T308 site was mapped and compared with WT. As expected, kainic acid induced phosphorylation of T308 in WT mice but not in R306C mice, indicating that this missense mutation disrupts MeCP2's activity-dependent interaction with NCoR. Finally, the authors asked whether T308A mice showed similar phenotypes to MeCP2 mutant R306C mice. Indeed, T308A mice showed reduced brain weight, motor coordination deficits in a rotarod test, and reduced threshold for seizure generation upon GABAA receptor antagonist (PTZ) treatment, when compared with WT littermates.

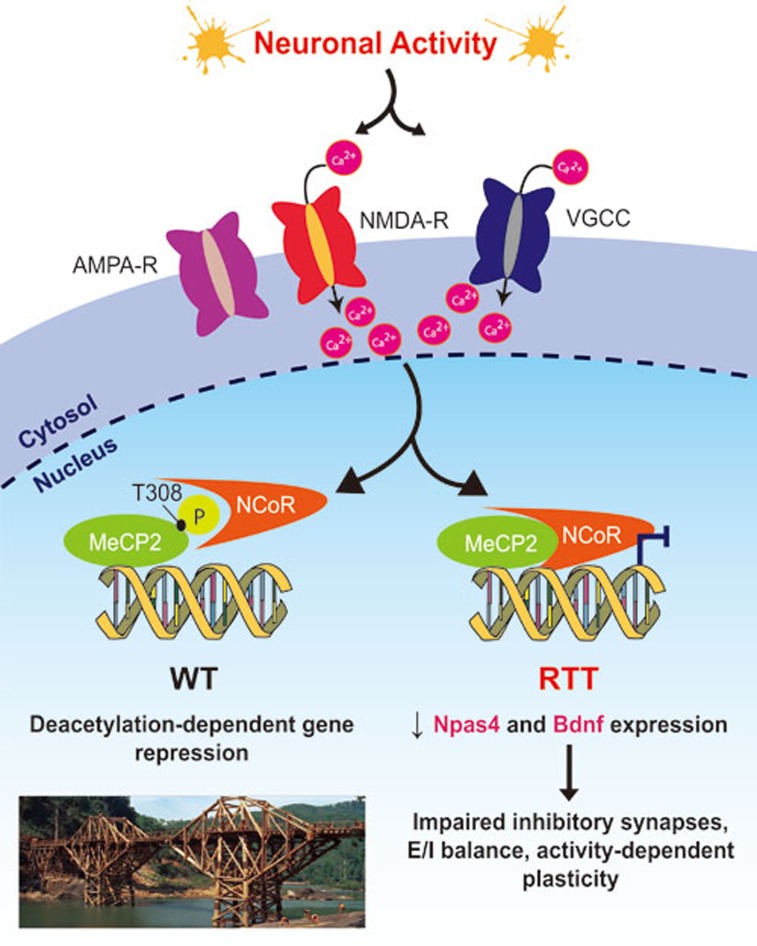

Thus, this study has identified a new activity sensor within MeCP2 (phosphorylation of T308; Figure 1) that controls its interaction with an important partner, the NCoR/SMRT co-repressor complex, to regulate global epigenetic status and gene expression. The location of missense mutations in MeCP2, in two major clusters — the methyl-binding domain (MBD) and transcription repression domain (TRD) — provides novel insights into their function. The R306C mutation located in the C terminus of the TRD causes mice to exhibit severe behavioral deficits resembling MeCP2-null mice7. T308 and its proximity to R306 may explain how MeCP2 may indeed function as an activity-dependent repressor. However, the interactions mediated by R306 and T308 are different, and together might provide inherent regulatory flexibility. Whereas R306C results in the loss of NCoR binding, T308A causes constitutive NCoR binding; both lead to RTT phenotypes, similar to the manner in which loss of MeCP2 and gain of MeCP2 can both lead to RTT-like symptoms. Importantly, the activity-dependent regulation of MeCP2/T308-mediated gene transcription is consistent with prolonged ocular dominance plasticity observed in the visual cortex of adult MeCP2 mutant mice10 (Figure 1), and with the delayed maturation of synapses in the mutant mice potentially due to altered Bdnf and Igf1 dependent signaling.

Figure 1.

Potential mechanism of activity-dependent transcriptional repression by MeCP2. Neuronal activity (induced in cultured neurons by KCl, kainic acid or bicuculline treatment) leads to membrane depolarization, causing Ca2+ to enter through synaptic NMDA receptors (NMDA-R) or membrane voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCC). This Ca2+ influx triggers a signaling pathway (mechanism not elucidated) to phosphorylate MeCP2 at residue Threonine (T) 308. Phosphorylation at T308 blocks the interaction of MeCP2 with the NCoR/SMRT co-repressor complex, which is responsible for transcriptional repression in wild-type (WT) neurons. Lack of phosphorylation at this residue due to missense point mutations may contribute to Rett syndrome (RTT): some of the genes that are regulated via this mechanism include Npas4 and Bdnf, which are required for development of inhibitory synapses onto excitatory neurons, E/I balance, and activity-dependent plasticity of circuits. Inset (left, bottom): Bridge on the river Khwae Yai in Thailand, as depicted in the 1957 Academy Award-winning film 'The Bridge on the River Kwai'. The central bridge spans bear a striking resemblance to the structure of DNA, and remind us that MeCP2 can act as an activity-dependent 'bridge' between NCoR and chromatin.

Like any thought-provoking study, this study also raises many unresolved yet addressable questions. How specifically does T308 influence transcription of Npas4 and Bdnf, but not other activity-dependent genes? Does activity differentially regulate T308 phosphorylation in distinct cell types, and if so, how? How do the structural and functional properties of excitatory and inhibitory interneuron types change in T308A mice? How might such changes alter E/I balance and affect seizures or plasticity, including learning and memory, in RTT? Is glial MeCP2 regulated in a similar manner? How do these nuclear changes link to synapses and the machinery underlying synaptic transmission and circuit function? Does this mechanism of activity-dependent gene regulation explain the regression of function at later developmental ages that is a hallmark of RTT? As the RTT field advances into a more refined set of functions and mechanisms attributable to individual components of its heterogeneous genotype, we can begin to envision a mutation-specific understanding of the disorder. Such a prospect would certainly be advanced by studying site-specific mutations using recent genome-editing techniques in human iPS-derived neurons, along with their isogenic controls.

References

- Chahrour M, Zoghbi HY. Neuron. 2007. pp. 422–437. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Banerjee A, Castro J, Sur M. Front Psychiatry. 2012. p. 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Guy J, Cheval H, Selfridge J, et al. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011. pp. 631–652. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cohen S, Gabel HW, Hemberg M, et al. Neuron. 2011. pp. 72–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ebert DH, Gabel HW, Robinson ND, et al. Nature. 2013. pp. 341–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chahrour M, Jung SY, Shaw C, et al. Science. 2008. pp. 1224–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lyst MJ, Ekiert R, Ebert DH, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2013. pp. 898–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lin Y, Bloodgood BL, Hauser JL, et al. Nature. 2008. pp. 1198–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Maya-Vetencourt JF, Tiraboschi E, Greco D, et al. J Physiol. 2012. pp. 4777–4787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tropea D, Giacometti E, Wilson NR, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009. pp. 2029–2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]