Abstract

Objective

Palpable tendon friction rubs (TFRs) in systemic sclerosis (SSc) have been associated with diffuse cutaneous skin disease, increased disability and poor survival. Our objective was to quantify the prognostic implications of palpable TFRs on the development of disease complications and longer-term mortality in an incident cohort of early diffuse SSc patients.

Methods

We identified early diffuse SSc patients (disease duration < 2 years from the first SSc symptom) first evaluated at the Pittsburgh Scleroderma Center between 1980-2006 and found to have palpable TFRs. These were matched 1:1 with the next consecutive early diffuse SSc patient without TFR as a control. All had two or more clinic visits and five years of follow-up from the first visit.

Results

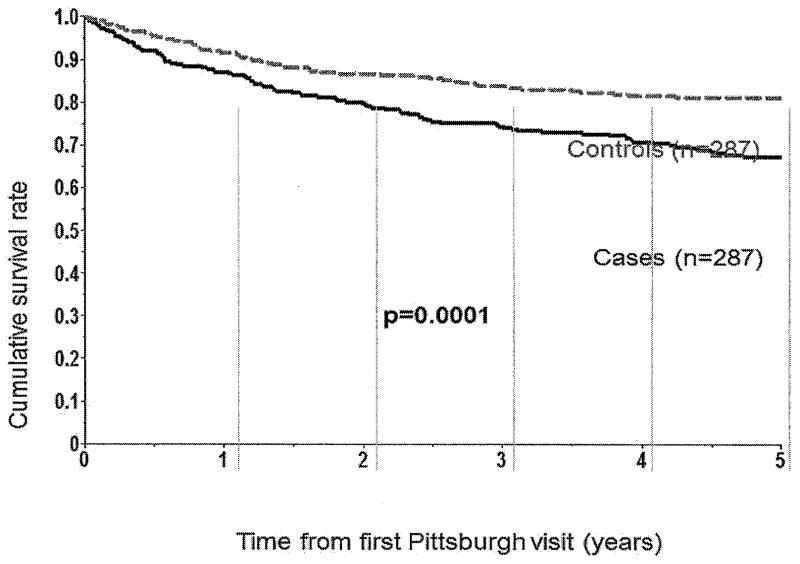

287 early diffuse SSc patients with TFR were identified and matched to 287 controls. The mean disease duration was 0.82 years in TFR patients and 1.04 years in controls. Mean follow-up was 10.1 years in TFR patients, and 7.9 years in controls. Over the course of their illness, patients with TFR had a greater than two-fold risk of developing renal crisis, cardiac and gastrointestinal disease complications, even after adjustment for other known factors. Patients with TFR had poorer five and ten year survival rates.

Conclusions

Patients with early diffuse SSc having one or more TFRs are at increased risk of developing renal, cardiac and gastrointestinal involvement before and after their first Scleroderma Center visit, and have reduced survival. Patients presenting with TFRs should be carefully monitored for serious internal organ involvement.

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a chronic, multisystem autoimmune disease characterized by vascular abnormalities, inflammation and fibrosis. Its two clinical subsets include limited cutaneous (including SSc sine scleroderma) and diffuse cutaneous disease. Patients with diffuse SSc generally develop internal organ complications early in disease (1) and have reduced survival (2-4).

Tendon friction rubs (TFRs) were first observed by Westphal in 1876 (5) and later characterized by Shulman et al.(6). Rodnan and Medsger (7) described the TFR as a ‘leathery, crepitus feel’ on palpation during active or passive motion. In a large prevalent observational cohort of both limited and diffuse SSc patients we previously concluded that TFRs were associated with diffuse disease, shorter disease duration, reduced survival, and renal and cardiac involvement (8-9). Khanna et al. (10) examined a small number of early diffuse SSc clinical trial participants and found that changes in TFRs correlated with changes in skin thickness score and the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ-DI) over a two-year follow-up period.

The objective of this study was to quantify the prognostic implications of palpable TFRs in an incident cohort of early diffuse SSc patients. It overlaps our previous publication (8), but is methodologically superior because of case-control analysis focused on early diffuse SSc patients, control for temporal trends, and adjusted risk quantification analysis for organ-specific long-term outcomes.

Patients and Methods

Patient Selection

We identified all early diffuse SSc seen for an initial visit at the University of Pittsburgh Scleroderma Clinic between January 1, 1980 and December 31, 2006. Early disease was defined as the presence of skin thickening proximal to the elbows or knees and < 2 years from the first symptom attributable to SSc. All patients had at least two visits, five years of follow-up and resided in the U.S. TFRs were considered present if palpated in the finger flexors or extensors, wrist flexors or extensors, olecranon bursa, shoulders, knees, anterior or posterior ankles with active motion.

Study Design

We used case-control methodology. To control for temporal trends, each case (TFR present at the first visit) was matched to the next consecutive patient presenting with early diffuse SSc who did not have TFRs (control) at any visit.

Data Collection

All patients had a comprehensive initial visit with evaluation of symptoms, physical examination, laboratory and serologic results, objective internal organ tests (pulmonary function tests, chest CT scan, echocardiogram, electrocardiogram, esophagram, etc.). At follow-up clinic visits all had a SSc-specific history and examination performed. Living patients not seen in clinic during 2011 were mailed a questionnaire to help in obtaining objective test results and to determine the time and severity of internal organ involvement.

Survival

Survival as of December 31, 2011 was obtained from the Social Security Death Index. Cause of death was determined by medical record review or discussion with physicians. If no records were available, the National Death Index was used to obtain death certificate information and reviewed in the context of known clinical information. Additional contacts with physicians or family, if available, were made.

Definitions of Internal Organ Involvement

Organ system involvement was defined as previously published (11) for renal, cardiac, gastrointestional, pulmonary fibrosis or restrictive lung disease, pulmonary hypertension and muscle disease. Severe peripheral vascular disease was defined as digital tip ulcers or gangrene. Joint contractures were assessed of the DIP, PIP, elbows and knees. Skin was assessed by the modified Rodnan skin score (mRss), and also by the skin thickness progression rate (STPR) which is calculated as: skin score at visit/(date of exam – date of skin onset). For example, if skin thickness (fingers swollen and never returned to normal size) began six months before the first visit where the mRss was 18, the STPR is 18/0.5 years = 36 per year. STPR groups were defined as slow (<25/year), intermediate (25-44/year) or rapid (≥45/year) (11).

Autoantibody Identification Methods

Anti-topoisomerase I was detected by Ouchterlony immunodiffusion and RNA polymerase III by protein immunoprecipitation. All other SSc autoantibodies were identified as previously reported (12).

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared between the TFR and no TFR patients using t-tests, Chi-square and non-parametric tests. The risk of developing internal organ involvement (bivariate analysis) was assessed using conditional logistic regression, and then adjusted analysis performed with a cut-off value of p≤ 0.05. Cumulative survival was calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Age and gender adjusted analysis was performed using Cox proportional hazards.

Results

From 1980 to 2006, 3010 patients with SSc were initially evaluated. Of these, 1296 had diffuse SSc, and 793 presented within two years of symptom onset. At the first visit 403 had one or more TFRs; 287 were seen ≥2 times with five plus years of follow-up. There were no differences in the 287 cases and the 116 patients seen only once with respect to age, gender, race or organ involvement other than a lower skin score (27.8 vs. 30.8; p = 0.005) and greater gastrointestinal involvement frequency (44% vs. 23%; p < 0.001) in cases at presentation.

Of the combined 574 case and control patients, 293 (52%) were alive as of December 31, 2011. Of the 127 living cases 71 (56%) had been seen within a year, and 39 of the other 56 (70%) returned questionnaires. Of 166 living controls, 75 (45%) had been seen and 37/91 (40%) returned questionnaires. Two hundred thirty-six (41%) patients in this cohort were also included in the Steen (8) report, although in this study there was a longer mean follow-up (6.3 vs 10.4 years), and more updated and accurate organ system information.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the TFR and no-TFR early diffuse SSc patients are presented in Table 1. There was no difference in mean age or gender. There were more Caucasians in the TFR (94% vs. 89%; p=0.01). Patients with TFR had a shorter median disease duration at first visit (0.83 years vs 1.04 years; p <0.0001), and a higher mean mRss (27.8 vs. 23.0; p< 0.0001). Thus, TFR patients had increased STPR (p <0.0001). The mean body mass index (BMI) was lower for TFR patients (p=0.04), but normal in both groups. TFRs were noted most frequently at the ankles (59%), followed by the fingers (43%), knees (37%), wrists (36%), olecranon bursae (25%) and shoulders (9%).

Table 1. Characteristics at first visit for patients with TFR* (cases), and without TFR (controls).

| TFR Cases n=287 |

Controls n=287 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| DEMOGRAPHICS | |||

| Mean age at first visit in years ± SD | 49.0 ±13.7 | 48.3 ± 14.5 | 0.52 |

| Female | 77% | 76% | 0.83 |

| Caucasian | 94% | 89% | 0.01 |

| DISEASE CHARACTERISTICS | |||

| Median disease duration in years† (IQR) | 0.83 (0.61, 1.13) | 1.04 (0.70, 1.48) | < 0.0001 |

| Median follow-up in years from first visit (IQR) | 10.4 (4.7, 16.8) | 7.9 (2.5, 16.6) | 0.01 |

| Mean modified Rodnan skin score ± SD | 27.8 ±10.9 | 23.0 ±10.9 | < 0.0001 |

| Skin thickness progression rate | 21% | 43% | <0.001 |

| slow | 34% | 32% | |

|

intermediate

rapid |

45% | 25% | |

| Mean body mass index ± SD | 23.5 ±4.1 | 24.5 ±4.7 | 0.04 |

| PRE-EXISTING INTERNAL ORGAN INVOLVEMENT | |||

| Renal crisis | 15% | 9% | 0.06 |

| Cardiac | 15% | 8% | 0.01 |

| Pulmonary (restrictive physiology or fibrosis) | 20% | 32% | 0.0006 |

| Gastrointestinal involvement | 51% | 42% | 0.04 |

| Skeletal muscle | 5% | 13% | 0.01 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 2% | 1% | 0.13 |

| Severe peripheral vascular ‡ | 6% | 4% | 0.24 |

| Joint contractures | 83% | 69% | 0.0002 |

| AUTOANTIBODIES | 0.35 | ||

| Anti-topoisomerase I | 70/274 | 62/275 | |

| Anti-RNA polymerase III | 156/259 | 137/254 | |

| Anti-U3RNP | 6/249 | 12/237 | |

| Anti-centromere | 5/280 | 3/283 | |

| Anti-U11/U12RNP | 3/224 | 2/246 | |

| Anti-Ku | 3/258 | 6/252 | |

| Anti-U1RNP | 7/265 | 5/265 | |

| Anti-PM-Scl | 1/258 | 5/241 | |

TFR = tendon friction rub

defined as time from first symptom attributable to scleroderma to the first Pittsburgh visit

digital ulcers or gangrene

At the first Pittsburgh visit, TFR patients already had significantly increased rates of cardiac (15%) and gastrointestinal involvement(51%), compared to 8% and 42%, respectively, in controls (Table 1). For cardiac involvement there was no difference in the frequency of pericardial effusion or cardiomyopathy. Patients with TFR more often had joint contractures (83% vs.69%), but had lower rates of pulmonary fibrosis or restrictive lung disease (20% vs. 32%; p= 0.0006), and skeletal muscle involvement (5.2% vs. 13.3%; p =0.01). There were no differences in the frequencies of renal crisis or pulmonary hypertension.

There was no overall difference in the autoantibody profile of TFR and no-TFR patients (p=0.35). The majority of all patients were anti-RNA polymerase III positive (57%), and 24% had anti-topoisomerase-I antibody. The remainder had other SSc-associated antibodies, and 9% had no identified SSc-related antibody. There was no difference in the frequency of prednisone, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate or d-penicillamine use prior to or prescribed at the first visit.

Organ Involvement

Cases were followed for a median of 10.4 years, and controls for 7.9 years after the first visit. During follow-up, cases were three times more likely to develop renal crisis (Table 2), and this risk increased to 3.77 times more likely (95% CI 1.70 – 8.34) after adjusting for anti-RNA polymerase III antibody, which has been previously associated with renal crisis (13). After additional adjustment for STPR (11), TFR cases continued to demonstrate a 3.67 times increased occurrence of new renal crisis compared with no-TFR controls. Patients with TFRs were 3.71 times more likely (95% CI 1.69 – 8.12) to develop cardiac involvement during follow-up, and 4.6 times (95% CI 2.00 – 10.36) more likely to develop gastrointestinal involvement (Table 2). There was a marginally increased risk of later pulmonary fibrosis or restrictive lung disease, and no significantly increased risk of later pulmonary hypertension, severe peripheral vascular disease, joint contractures or skeletal muscle involvement.

Table 2. Risk of developing subsequent internal organ involvement in early diffuse systemic sclerosis patients presenting with tendon friction rubs at the first visit.

| Odds Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Renal crisis | 3.05 | 1.59 – 5.87 | 0 .0008 |

| Cardiac | 3.71 | 1.69-8.12 | < .0001 |

| Pulmonary * | 1.84 | 1.05 – 3.22 | 0.03 |

| Gastrointestinal | 4.57 | 2.00 – 10.36 | 0.0003 |

| Skeletal muscle | 4.00 | 0.85 – 18.84 | 0.08 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 1.40 | 0.71 - 2.78 | 0.33 |

| Severe peripheral vascular † | 1.10 | 0.47 – 2.59 | 0.83 |

| Joint contractures | 2.67 | 0.85 – 18.84 | 0.15 |

|

| |||

| ADJUSTED FOR SIGNIFICANT BASELINE DIFFERENCES ‡ | |||

| Renal crisis | 2.66 | 1.23 – 5.75 | 0.01 |

| Cardiac | 3.26 | 1.35 – 7.84 | 0.009 |

| Gastrointestinal | 5.14 | 1.74 – 15.17 | <0.0001 |

| Pulmonary * | 2.06 | 0.95 – 4.46 | 0.07 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 1.41 | 0.56 – 3.51 | 0.47 |

| Severe peripheral vascular † | 1.70 | 0.46 – 6.31 | 0.43 |

| Joint contractures | 0.89 | 0.49 – 1.63 | 0.58 |

interstitial lung disease or restrictive lung disease

defined as presence of digital ulcers or gangrene

race, disease duration, baseline modified Rodnan skin score and skin thickness progression rate group

To further understand the impact of TFRs, we adjusted for baseline differences in the case and control groups, including race, disease duration, baseline mRss and STPR (Table 2). After adjustment, patients with TFRs continued to be at significantly increased risk to develop renal crisis (OR 2.66; 95% CI 1.23 – 5.75), cardiac (OR 3.26; 95% CI 1.35 – 7.84) and gastrointestinal involvement (OR 5.14; 95% CI 1.74 – 15.17). There was no increased risk of developing pulmonary involvement, pulmonary hypertension, digital ulcers or joint contractures in those with TFRs. There were too few new cases of muscle involvement to perform regression analysis.

Over the course of the illness, including both before and after first evaluation, patients with TFRs were 2.3 times more likely to develop renal crisis (95% CI 1.52 – 3.49; p< 0.0001). This risk was unchanged when adjusted for anti-RNA polymerase III antibody and STPR. Patients with TFRs were 2.43 times more likely to develop cardiac disease, and 2.25 times more likely to develop gastrointestinal involvement. There was no increased risk to develop pulmonary hypertension, severe peripheral vascular disease, skeletal myopathy or pulmonary involvement.

Survival

Five year unadjusted cumulative survival was significantly reduced in patients with TFRs (68% vs. 81% in controls; p < 0.0001), as depicted in Figure 1. Ten year cumulative survival was also significantly reduced (p< 0.0001) at 55% in TFR cases compared to 64% in no-TFR controls. After age and gender adjustment, TFR cases were 1.8 times more likely to die at five years (95% CI 1.21 – 2.58; 9= 0.003). BMI did not change the results. In both cases and controls, 66% of all deaths were judged to be SSc-related, with <2% undetermined cause of death.

Figure 1. Five-year cumulative survival in patients with tendon friction rubs compared to controls.

Discussion

The tendon friction rub is a physical examination finding highly specific for SSc and has been linked to diffuse skin involvement, increased disease severity and disability (10), and poor survival (8-9). In this large case-control study of an incident cohort of early diffuse SSc patients, we examined the long-term risks of internal organ involvement in patients presenting with TFRs and demonstrated a substantially increased risk of developing renal crisis, cardiac and gastrointestinal complications compared to those without TFRs. We have quantified these risks, and adjusted for other known associations to demonstrate a 3-5-fold greater risk of developing these complications throughout the course of the disease, distinguishing this from prior TFR literature (8-10). We confirmed prior reports of decreased survival in patients with TFR. These findings have important implications for monitoring of early diffuse SSc patients with TFRs.

Consistent with prior publications (8, 10), the most frequent sites of TFRs were the ankles, fingers and wrists in this study. Although more patients with TFRs present with joint contractures, over time persons with TFRs are not more likely to have joint contractures than those without TFRs. We have also demonstrated an increased risk of developing severe peripheral vascular involvement with digital tip ulcers or gangrene in TFR patients. This difference was not present at baseline, suggesting that TFR patients may later develop more severe peripheral vascular involvement than no-TFR patients.

Similar to others studies (8, 9), patients with TFRs have a poorer long-term survival which persists after age and gender adjustment. We also showed no increased rate of SSc-associated cause of death compared to controls, which has not been examined in prior studies.

Our earlier report (9) suggested an association between TFRs and anti-topoisomerase I antibody, which we did not confirm. The most frequent serum autoantibody in our cohort was anti-RNA polymerase III, present in >50% of patients, likely related to the restriction to early diffuse SSc. However, this antibody positivity did not explain the increased risk of renal crisis, as the nearly four-fold increased risk of developing renal crisis persisted independent of RNA polymerase III.

Detection of TFRs is admittedly dependent on examiner skill and experience. If TFRs are accepted as important in routine clinical care and in clinic trials, physician training in the proper technique for detecting TFRs should be provided, such as is the case for the mRss.

There are limitations of this study. First, it is a single center study from a tertiary care scleroderma center with a Caucasian predominant population, limiting its generalizability. Second, despite our efforts, we were unable to ascertain up-to-date organ assessment testing and information on all patients. The follow-up questionnaire response rate was higher in patients with TFRs, and these patients had a longer mean follow-up than the no-TFR patients. This could have biased the results by reducing the likelihood of capturing later new organ involvement in controls. Finally, this study covers three decades, and thus differences in the ascertainment of organ system testing may affect the incidence and prevalence of complications and survival. We have attempted to control for such differences by temporally matching cases and controls.

In summary, the TFR is an easily detected physical examination finding which occurs in early diffuse SSc patients and identifies individuals at high risk for renal crisis, cardiac and gastrointestinal complications. TFRs are associated with decreased survival. Consideration of these factors should be made in monitoring and management of patients presenting with early diffuse SSc and one or more palpable TFRs.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Domsic was supported by a National Institutes of Health Award (NIAMS K23 AR057845-03).

Footnotes

The authors have received no financial support for this manuscript which could cause any potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Black CA, Denton CP. Management of systemic sclerosis. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34:3–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/34.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silman AJ. Scleroderma and survival. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991;50:267–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.50.4.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hesselstrand R, Scheja A, Akesson A. Mortality and causes of death in a Swedish series of systemic sclerosis patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57:682–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.11.682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scussel-Lonzetti L, Joyal F, Raynauld JP, Roussin A, Rich E, Goulet JR, et al. Predicting mortality in systemic sclerosis: analysis of a cohort of 309 French Canadian patients with emphasis on features at diagnosis as predictive factors for survival. Medicine. 2002;81:154–67. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westphal C. ZweiFalle Von Schlerodermie. ChariteAnnalen (Berlin) 1976;3:341–60. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shulman LE, Kurban AK, Harvey AM. Tendon friction rubs in progressive systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) Trans Assoc Am Physician. 1961;74:378–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodnan GP, Medsger TA. The rheumatic manifestations of progressive systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) OrthopRelat Res. 1968;57:81–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steen VD, Medsger TA., Jr. The palpable tendon friction rub: an important physical examination finding in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1146–51. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199706)40:6<1146::AID-ART19>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steen VD, Powell DL, Medsger TA., Jr. Clinical correlations and prognosis based on serum autoantibodies in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:196–203. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khanna PP, Furst DE, Clements PJ, Maranian P, Indulkar L, Khanna D. Tendon friction rubs in early diffuse systemic sclerosis: prevalence, characteristics and longitudinal changes in a randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology. 2010;49:955–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Domsic RT, Rodriguez-Reyna T, Lucas M, Fertig N, Medsger TA., Jr. Skin thickness progression rate: a predictor of mortality and early internal organ involvement in diffuse scleroderma. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:104–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.127621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kao AH, Lacomis D, Lucas M, Fertig N, Oddis CV. Anti-signal recognition particle autoantibody in patients with and patients without idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:209–15. doi: 10.1002/art.11484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Penn H, Howie AJ, Kingdon EJ, Bunn CC, Stratton RJ, Black CM, et al. Scleroderma renal crisis: patient characteristics and long-term outcomes. QJM. 2007;100:485–94. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]