Abstract

Background

Non-traumatic dental condition (NTDC) visits frequently occur in emergency departments (EDs) and physicians’ offices (POs), but little is known about whether racial/ethnic disparities exist in Medicaid NTDC visit rates to EDs and POs.

Methods

All Medicaid dental claims in Wisconsin from 2001–2003 were analyzed to examine factors associated with NTDC visits to EDs and POs. Bivariable and multivariable analyses were performed; independent variables examined included race/ethnicity, age, gender, dental health professional shortage area (DHPSA) designation, and Urban Influence Code (UIC) for county of residence.

Results

956,774 NTDC visits made during 1,718,006 person-years were evaluated; 4.3% of visits occurred in EDs/POs. Native Americans, African-Americans, and enrollees of unknown race/ethnicity had the highest unadjusted ED/PO visit rates for NTDCs. African-Americans, Native-Americans, adults, and residence in partial or entire DHPSAs had significantly higher adjusted rates of NTDC visits to EDs. Significantly higher adjusted NTDC visit rates to POs were observed for Native-Americans, adults, and enrollees residing in entire DHPSAs, but African-Americans had a significantly lower adjusted rate.

Conclusions

Native Americans, those residing in entire DHPSAs, and adults have significantly higher risks of NTDC visits to EDs and POs; African-Americans are at increased risk of ED visits but at decreased risk of PO visits for NTDCs.

Clinical Implications

Reductions in Medicaid visits to EDs and POs and the associated costs might be achieved by improving dental care access and targeted educational strategies among minorities, DHPSA residents, and adults.

Keywords: Medicaid, racial/ethnic disparities, non-traumatic dental conditions, emergency department, DHPSAs

INTRODUCTION

The Medicaid program is the largest source of public funding for medical and dental services in the US,1, 2 covering millions of the disabled, elderly, blind, pregnant women, and children classified as poor, based on federal poverty level guidelines.1,2 In 2004, 41.3 million Americans were insured through Medicaid.3 Under Medicaid, the Early Periodic, Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment program requires that basic dental services be covered for children,1 but not adults, although basic dental services are covered for adults in some states, such as Wisconsin.

Emergency department (ED) visits in the US increased by 26% from 1993 to 2003.4,5 Dental complaints were responsible for 3 million visits to EDs in the US from 1997 to 2000, with an average of 738,000 visits annually.6 Recent national data suggest that dental problems account for 0.2% of visits to physician offices (POs) and 0.9% of ED visits.7 Dental conditions are best treated in dental offices, where appropriate procedures and continuity of care can be provided by a regular dental provider. Most patients presenting to EDs or POs with dental conditions receive only temporary treatment, antibiotics or analgesics, and referral for follow-up with a dental provider.6 The transitory nature of dental care received in EDs and POs has important cost implications, as the Medicaid system is forced to pay for largely unnecessary ED and PO visits, in addition to subsequent visits to dental providers.

Although dental care needs are best addressed in primary care settings,8 barriers exist to accessing primary dental care, especially for Medicaid enrollees. These include geographic maldistribution of dentists, with only 6% of dental needs met in the 1198 health professional shortage areas in the US,9 inadequate numbers of dentists treating Medicaid enrollees,10,11 and low Medicaid reimbursement rates.10,12 These barriers persist despite overall improvement in the oral health of most Americans, with the poor and racial/ethnic minority groups disproportionately affected by dental disease.9 The use of EDs and POs for NTDCs has received limited attention.13–15 In particular, not enough is known about factors associated with NTDC visits to EDs and POs among Medicaid enrollees. Our study objective, therefore, was to identify factors associated with NTDC visits to EDs and POs among Medicaid enrollees.

METHODS

Data Source

The data source was the Electronic Data Systems of Medicaid Evaluation and Decision Support (MEDS) database for Wisconsin from 2001–2003. This database contains all Medicaid claims for the state of Wisconsin, and is managed by the Division of Health Care Financing in the Wisconsin Department of Health and Family Services. The database consists of information on age, gender, date of service, International Classification of Diseases 9th revision Clinical Modifications (or ICD-9-CM) codes for the presenting dental condition, patients’ race/ethnicity, and county of residence.

Definition of Non-Traumatic Dental Conditions

Non-traumatic dental conditions were defined as any claim with the following ICD-9-CM codes: 521.0–521.9 (diseases of dental hard tissues of teeth); 522.0–522.9 (diseases of pulp and periapical tissues); 523.0–523.9 (gingival and periodontal diseases); 525.3 (retained dental root); 525.9 (unspecified disorder of the teeth and supporting structures); and 873.63 (internal structures of mouth, without broken tooth).16 These ICD-9-CM codes for NTDC visits are identical to those used in other published studies analyzing dental visits to EDs and POs.8,13

County-Level Information

County of residence at the time of the claim was used to define two county-level variables: Dental Health Professional Shortage Area (DHPSA) designation, and Urban Influence Code (UIC). Classification of DHPSA and UIC was done on a county level (there are 72 counties in Wisconsin), rather than by zip codes. DHPSA designation was developed by the federal government to meet the need for better programs in communities with high unmet dental needs.17,18 In this study, we used the classification followed in a recent oral health report by the Wisconsin Department of Health and Family Services.19 Under this classification scheme, a county is considered an entire DHPSA when it meets the criteria established by the Bureau of Health Professionals, which are “that the area should be a rational area for the delivery of dental services; the population to full-time dentist ratio should be less than 5,000:1 but greater than 4,000:1 and has unusually high needs for dental services or insufficient capacity of existing dental providers; or dental professionals in the contiguous area are over utilized, or excessively distant, or inaccessible to the population of the area under consideration.”17,18

The 2003 UICs, published by the US Department of Agriculture, were used as a measure of the rurality of the county of residence for each enrollee making a claim.20 The UICs use population and commuting data from the 2000 Census to classify the 3,141 US counties and county equivalents into 12 groups. For the purposes of this study, we only used the three major classification levels: metropolitan, micropolitan, and rural.

Race/Ethnicity, Age, and Missing Data

Enrollees’ self-designated race/ethnicity was available from the state database in the following categories: White, African-American, Latino, Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American, other, and unknown. Age groups were dichotomized as children (≤18 years old) and adults (>18 years old). Observations with missing information on age or county of residence were excluded.

Database Creation Process

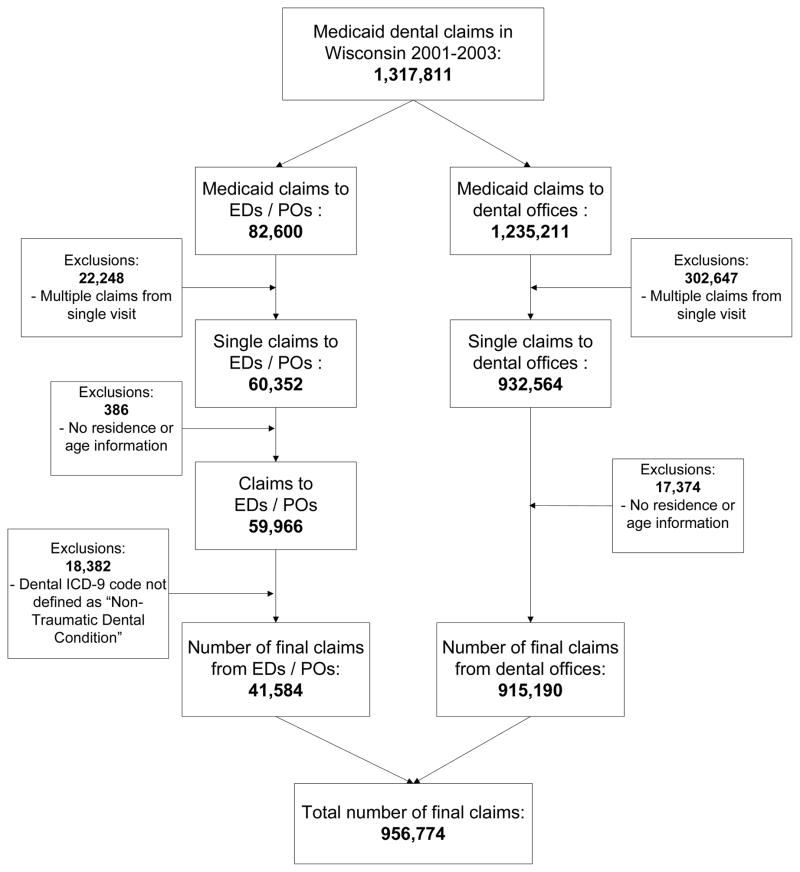

The database of those enrolled in Medicaid in Wisconsin from 2001 to 2003 included 1,317,811 claims (Figure). Of these, 1,235,211 records were claims from dental office visits and 82,600 were claims from ED and PO visits. Claims were merged by patient identification number, date of service, and site of visit, to account for multiple charges during a single visit. For ED claims, the facility claim was used instead of the claim from the attending physician. After removing multiple charges for the same visit, records with no information on county of residence or age, and claims with ICD-9 codes not classified as NTDCs, the number of records was reduced to 915,190 dental office visits and 41,584 ED/PO visits for final analysis.

Figure.

Flowchart of database creation for Wisconsin Medicaid dental claims analyses.

Statistical Analyses

We evaluated factors associated with rates of NTDC visits to dental offices, EDs, and POs. Because the number of Medicaid enrollees fluctuates from month to month, rates were calculated relative to the number of “person-years” of enrollment. For example, a person enrolled for an entire year contributes one person-year. Data were extracted from the MEDS database that delineated the number of Medicaid enrollees per month within each county, subdivided by age group, gender, and race/ethnicity. We then calculated separate rates for each demographic and county subgroup, by dividing the number of visits by the number of Medicaid enrolled person-years. Rate ratios were calculated to assess the marginal association of each factor with the rate of visits to each service provider category. Multivariable generalized Poisson regression models, accounting for overdispersion, were fit separately for visits to EDs and POs, to assess the association of each factor, adjusting for relevant covariates. Regression models were performed using race/ethnicity, age group, gender, DHPSA designation, and UIC as the independent variables.

We also examined potential interactions between race/ethnicity and DHPSA, race/ethnicity and UIC, and DHPSA and UIC. Although a few small, statistically significant interactions were noted, the interactions did not alter the main significant findings in multivariable models, and the interactions were inconsistent, only accounted for a small amount of variance in models, may reflect large sample sizes, have limited dental public health implications, and may produce models that are over-fitted. We therefore chose to omit the findings of multivariable models that included interaction terms.

All analyses include a DHPSA classification and UIC based on the county of residence at the end of 2003 for those patients whose residence was missing at the time of the visit. Because these subjects could potentially bias the results by having moved between the time of the claim and the end of 2003, we also performed all analyses excluding these subjects. The results were similar to those presented, and are not shown. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS© software Version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). An alpha level of 0.05 was used throughout to denote statistical significance.

RESULTS

Study Population Characteristics

The Medicaid population in Wisconsin totaled 1,718,006 person-years of enrollment during 2001 to 2003 (Table 1). Adults and children comprised equal proportions of this population, but females outnumbered males by 16%. Almost half of the population was white; African-Americans were the most common racial/ethnic minority (19%), followed by Latinos (8%), Asian/Pacific Islanders (3%), and Native American (2%), and the race/ethnicity was unknown for 20% of enrollees. About three-quarters of the population resided in metropolitan counties, approximately half resided in partial DHPSAs, and almost one-quarter resided in entire DHPSAs.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Medicaid-enrollees and NTDC Medicaid visits in Wisconsin in 2001–2003.

| Characteristic | % of Medicaid-Enrollees* (N=1,718,006) | % of all NTDC Visits (N=956,774) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age | ||

| ≤18 years old | 50.9 | 46.2 |

| >18 years old | 49.1 | 53.8 |

|

| ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 41.8 | 39.1 |

| Female | 58.2 | 60.9 |

|

| ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 48.9 | 53.0 |

| African-American | 18.8 | 15.0 |

| Latino | 7.5 | 6.1 |

| Asian/Pacific-Islander | 2.8 | 2.6 |

| Native American | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| Other | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| Unknown | 19.5 | 21.0 |

|

| ||

| Urban Influence Code | ||

| Metropolitan | 72.5 | 69.3 |

| Micropolitan | 11.0 | 11.9 |

| Rural | 16.4 | 18.8 |

|

| ||

| Dental Health Professional Shortage Area | ||

| Entire | 22.7 | 24.8 |

| Partial | 49.0 | 45.1 |

| None | 28.3 | 30.1 |

|

| ||

| Visit site | ||

| ED/PO | 4.3 | |

| Dental Office | 95.7 | |

Expressed as person-years

Characteristics of Medicaid Enrollees Making NTDC Visits and Condition Codes

Adults made more NTDC visits than children, and almost two-thirds of visits were made by females (Table 1). About half of NTDC visits were by whites, 15% were by African-Americans, and 21% were by those of unknown race/ethnicity.

Among ED/PO NTDC claims “dental disorder unspecified” (525.9) was the most frequent ICD-9-CM code, accounting for 45% of visits; dental caries (24%) and periapical abscesses (19%) were the next most common codes (data not shown). Differences were observed in diagnostic codes according to visit site and age (all of which were statistically significant; data not shown). “Dental disorder unspecified” and dental caries comprised 32% and 22% of ED pediatric claims, but 17% and 43% of PO pediatric claims respectively. Among adults, 55% of ED visits were for “dental disorder unspecified” compared with 38% for PO visits. The second most common diagnosis for adult ED visits was dental caries (25%) and for PO visits, periapical abscesses (27%).

Bivariate Analysis of Factors Associated with NTDC Visits

NTDC visit rates were 242 per 10,000 person-years of enrollment to either EDs or POs and 5,327 per 10,000 person-years to dental offices (Table 2). Males had significantly lower crude rates than females for NTDC visits both to EDs/POs and to dental offices. Compared with children, adults had almost four times the NTDC visit rate to ED/POs, but only a slightly higher rate for NTDC visits to dental offices. African-Americans, Latinos, and Asian/Pacific Islanders had significantly lower NTDC rates for visits to dental offices compared with whites, but Asian/Pacific Islanders were the only minority group with an ED/PO NTDC visit rate that significantly differed from whites (rate ratio=0.33; 95% CI, 0.14, 0.82). Among NTDC visits to dental offices, significantly lower rates were found for enrollees residing in partial DHPSAs, higher rates were found for micropolitan and rural enrollees, but no other significant findings were noted for any other comparisons.

TABLE 2.

Bivariate analyses of factors associated with NTDC visit rates to EDs/POs and dental offices for Medicaid enrollees.

| Characteristic | EDs/POs | Dental Offices | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| NTDC Visit Rate per 10,000 Person-Years† | Unadjusted Rate Ratio (95% CI) | NTDC Visit Rate per 10,000 Person-Years† | Unadjusted Rate Ratio (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||

| Total | 242 | - | 5327 | - |

|

| ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 273 | Referent | 5561 | Referent |

| Male | 200 | 0.73 (0.61, 0.88) | 5002 | 0.90 (0.86, 0.94) |

|

| ||||

| Age | ||||

| ≤ 18 years old | 100 | Referent | 5149 | Referent |

| > 18 years old | 389 | 3.87 (3.46, 4.33) | 5512 | 1.07 (1.02, 1.12) |

|

| ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 243 | Referent | 5783 | Referent |

| African-American | 252 | 1.04 (0.82, 1.31) | 4187 | 0.72 (0.69, 0.76) |

| Latino | 167 | 0.69 (0.46, 1.03) | 4396 | 0.76 (0.70, 0.82) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 81 | 0.33 (0.14, 0.82) | 4996 | 0.86 (0.77, 0.97) |

| Native American | 345 | 1.42 (0.79, 2.58) | 5384 | 0.93 (0.81, 1.08) |

| Other | 232 | 0.96 (0.36, 2.56) | 4674 | 0.81 (0.65, 1.00) |

| Unknown | 275 | 1.13 (0.91, 1.42) | 5711 | 0.99 (0.94, 1.03) |

|

| ||||

| DHPSA | ||||

| None | 223 | Referent | 5700 | Referent |

| Partial | 242 | 1.08 (0.87, 1.34) | 4877 | 0.86 (0.81, 0.90) |

| Entire | 265 | 1.19 (0.93, 1.52) | 5835 | 1.02 (0.97, 1.09) |

|

| ||||

| UIC | ||||

| Metropolitan | 243 | Referent | 5081 | Referent |

| Micropolitan | 252 | 1.04 (0.78, 1.38) | 5750 | 1.13 (1.06, 1.21) |

| Rural | 233 | 0.96 (0.75, 1.23) | 6129 | 1.21 (1.14, 1.28) |

Statistically significant findings are highlighted in bold.

Rates are expressed person-years of Medicaid enrollment

ED = Emergency Department PO = Physician’s Office

UIC = Urban Influence Code DHPSA = Dental Health Professional Shortage Area

Bivariate Analyses of Factors Associated NTDC Visits to EDs and POs

For NTDC visits to EDs, adults had four times the crude rate of children (Table 3). African-Americans and those of unknown race/ethnicity also had significantly higher crude ED visit rates, but none of the other racial/ethnic groups had rates significantly different from whites. Partial DHPSA residents had a higher rate of ED visits and rural residents a lower rate.

TABLE 3.

Bivariate analyses of factors associated with NTDC visit rates to EDs and to POs.

| Characteristic | EDs | POs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| NTDC Visit Rate per 10,000 Person-Years * | Unadjusted Rate Ratio (95% CI) | NTDC Visit Rate* | Unadjusted Rate Ratio (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||

| Total | 141 | - | 101 | - |

|

| ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 163 | Referent | 110 | Referent |

| Male | 111 | 0.68 (0.56, 0.83) | 89 | 0.81 (0.67, 0.97) |

|

| ||||

| Age | ||||

| ≤ 18 years old | 57 | Referent | 43 | Referent |

| > 18 years old | 228 | 4.00 (3.46, 4.63) | 161 | 3.71 (3.29, 4.18) |

|

| ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 127 | Referent | 116 | Referent |

| African-American | 188 | 1.48 (1.18, 1.86) | 64 | 0.55 (0.42, 0.72) |

| Latino | 87 | 0.68 (0.44, 1.07) | 80 | 0.70 (0.48, 1.01) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 18 | 0.15 (0.03, 0.66) | 63 | 0.54 (0.28, 1.04) |

| Native American | 193 | 1.52 (0.80, 2.89) | 152 | 1.32 (0.75, 2.32) |

| Other | 110 | 0.87 (0.27, 2.74) | 122 | 1.06 (0.45, 2.50) |

| Unknown | 166 | 1.31 (1.03, 1.66) | 109 | 0.94 (0.76, 1.17) |

|

| ||||

| DHPSA | ||||

| None | 121 | Referent | 102 | Referent |

| Partial | 158 | 1.30 (1.03, 1.65) | 84 | 0.82 (0.67, 1.02) |

| Entire | 129 | 1.06 (0.80, 1.42) | 136 | 1.34 (1.07, 1.67) |

|

| ||||

| UIC | ||||

| Metropolitan | 150 | Referent | 93 | Referent |

| Micropolitan | 134 | 0.90 (0.65, 1.23) | 118 | 1.27 (0.97, 1.66) |

| Rural | 108 | 0.72 (0.54, 0.97) | 125 | 1.34 (1.08, 1.68) |

Statistically significant findings are highlighted in bold.

Rates are expressed per person-years of Medicaid enrollment

ED = Emergency Department PO = Physician’s Office

UIC = Urban Influence Code DHPSA = Dental Health Professional Shortage Area

For NTDC visits to POs, adults also had about four times the crude rate of children, but African-Americans had a lower rate than whites (Table 3). Both entire DHPSA and rural residence were associated with significantly higher PO visit rates, but no other significant associations were noted.

Multivariable Analyses of Factors Associated with NTDC Visits to EDs and POs

Several factors were found to be significantly associated with NTDC visit rates to EDs, after adjustment in multivariable analyses (Table 4). Males had lower adjusted rates than females, but the adjusted rate for adults was more than four times that of children. Compared with whites, Native Americans (rate ratio [RR], 2.04; 95% CI, 1.50–2.76) and African Americans [RR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.51–1.94] had double the adjusted rates of NTDCs to EDs, whereas Asians/Pacific Islanders [RR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.10–0.41] had an adjusted rate that was five times lower. Significantly greater adjusted rates were seen for partial and entire DHPSAs and a lower rate for rural enrollees.

TABLE 4.

| Characteristic | Adjusted Rate Ratio (95% CI) for NTDC Visits to

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Emergency Department | Physicians’ Offices | |

|

| ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | Referent | Referent |

| Male | 0.91 (0.83, 0.99) | 1.00 (0.91, 1.10) |

|

| ||

| Age | ||

| ≤ 18 years old | Referent | Referent |

| > 18 years old | 4.20 (3.76, 4.70) | 3.70 (3.31, 4.12) |

|

| ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | Referent | Referent |

| Native American | 2.04 (1.50, 2.76) | 1.58 (1.18, 2.11) |

| African-American | 1.71 (1.51, 1.94) | 0.79 (0.68, 0.93) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.20 (0.10, 0.41) | 0.81 (0.58, 1.14) |

| Latino | 0.89 (0.72, 1.11) | 1.04 (0.86, 1.26) |

| Other | 1.41 (0.82, 2.43) | 1.77 (1.14, 2.75) |

| Unknown | 1.06 (0.95, 1.19) | 0.84 (0.75, 0.94) |

|

| ||

| DHPSA | ||

| None | Referent | Referent |

| Partial | 1.18 (1.04, 1.32) | 0.95 (0.84, 1.07) |

| Entire | 1.20 (1.04, 1.39) | 1.33 (1.17, 1.51) |

|

| ||

| UIC† | ||

| Metropolitan | Referent | Referent |

| Micropolitan | 0.99 (0.84, 1.16) | 1.00 (0.87, 1.16) |

| Rural | 0.72 (0.61, 0.85) | 0.93 (0.81, 1.07) |

Statistically significant findings are highlighted in bold.

Adjusted rate ratios were derived from Poisson regression models.

UIC = Urban Influence Code DHPSA = Dental Health Professional Shortage Area

For NTDC visits to POs, adults had almost four times the adjusted rate of children (Table 4). Compared with whites, Native Americans [RR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.18–2.11] and those of other race/ethnicity had about double the rate, whereas African-Americans [RR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.68–0.93] and those of unknown race/ethnicity had lower rates. Enrollees in entire DHPSAs had higher rates than those in non-DHPSAs, but no other significant findings were noted.

DISCUSSION

Relationship of Findings to Prior Work

This study is the first (to our knowledge) to identify associations between demographic/county-level factors and rates of NTDC visits to EDs and POs by Medicaid enrollees. A small number of studies have examined ED use for dental conditions in children.12,14,21,22 These studies consisted of non-probability samples with small sample sizes drawn from urban or local hospitals and dental-school emergency clinics, and most are descriptive in nature. Little is known about NTDC visits to EDs and POs on a state or national level, with the exception of two studies. One study examined use of POs for dental problems following changes in state adult Medicaid eligibility in Maryland,23 and the other analyzed data from the household component of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) to examine dental condition-related visits to non-dental healthcare providers.24 Findings from the MEPS study showed that about 3% of adults received care in EDs and 7% received care in other medical settings.24 In our study, 4% of NTDC visits occurred in EDs/POs, and adults had significantly higher rates of visits to both EDs and POs. This finding is consistent with prior work on medical care, which documented that those >18 years old are significantly more likely to use EDs for non-urgent medical or non-traumatic conditions.4 Other estimates of dental visits to EDs/POs include data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey indicating that 0.7% of all ED visits from 1997 to 2000 were for dental complaints and an estimated 4.1 million visits received a dental ICD-9 discharge diagnosis.6

Racial/Ethnic Disparities

Specific, substantial racial/ethnic disparities were identified in NTDC visits to EDs and POs, which persisted after adjustment for relevant covariates. Compared with whites, Native Americans had double the rate of NTDC visits to EDs and to POs, African-Americans had about double the rate of NTDC visits to EDs and enrollees of other race/ethnicity (which include multiracial person) had about double the rate of PO visits for NTDCs. These findings expand the growing list of racial/ethnic disparities in oral health and dental care, and are consistent with recent national data documenting that Native American, African-American, and multiracial children have higher adjusted odds of unmet dental care needs and having had no routine preventive dental visit in the past year.25 These new data are particularly concerning, given the substantial literature documenting that minorities have the highest risk for early childhood caries,26 dental caries,27 edentulousness,9 and oral cancer.9 Minority children have been documented to have a higher risk of untreated dental disease,28 with this lack of treatment associated with 52 million missed school hours/year,29 poor self-esteem, and an impaired ability to learn.30

Two findings merit further comment regarding lower rates of ED/PO use for certain minority groups. Compared with whites, African-Americans had lower adjusted rates of NTDC visits to POs, but higher rates of ED visits. This could be related to findings that African Americans are less likely to have a usual source of care and more likely to make ED visits.31 Asians/Pacific Islanders had significantly lower rates of NTDC visits to EDs and POs, but also had lower NTDC visits rates to dental offices. Low use of EDs and POs among Asians/Pacific Islanders is consistent with several studies in the medical literature documenting lower use of medical services in general.32–34 Possible explanations for this phenomenon might include better health status, language barriers to care, cultural norms regarding the need for care, and distrust of the western medical system.33,34 These results suggest that more research is warranted on utilization of dental services among Asian/Pacific Islanders.

DHPSA Findings

DHPSA designation was associated with NTDC visit rates to EDs and POs, with significantly higher rates documented for both EDs and POS in entire DHPSAs, and for EDs among enrollees in partial DHPSAs. DHPSA designation is a prerequisite for participation in state and federal programs designed to improve access to dental care.18 Studies have documented that higher numbers of racial/ethnic minorities live in health profession shortage area (HPSAs).35 Although DHPSA designation is mainly based on dentist-to-population ratios and unmet dental needs of the population,18 the designation appears to be a useful measure in deciding where to allocate resources aimed at reducing NTDC visits to EDs and POs. Our results suggest that a reduction in NTDC visits to EDs and POs might be achieved by establishing greater access to dental homes in DHPSAs.

Implications for Policy and Practice

The study findings indicate possible problems in the Medicaid system and how, when, and where enrollees seek appropriate dental care services for NTDCs. Although it may be impossible to completely eliminate NTDC visits to EDs and POs, even a small reduction in such visits can potentially result in substantial cost savings and in improvements in both dental and health care. For example, reducing only the ED-visit component of Wisconsin Medicaid NTDC visits to EDs and POs by 1% from 4.3% to 3.3% of all claims (equivalent to a reduction of 10,010 claims in the three-year study period [41,584 -31,574]) could result in estimated savings of more than $6.1 million for Medicaid (using published national data documenting an average expense of $637 per ED visit with one or more non-surgical services,36 and deducting the Medicaid expense ($25) of a dental office examination and periapical x-ray37), while simultaneously increasing use of dental homes (sites providing care that is accessible, continuous, comprehensive, coordinated, compassionate, family-centered, and culturally effective), and decreasing inappropriate use of overcrowded EDs.

A small reduction in rates of NTDC visits to EDs and POs could yield considerable cost savings and improvements in delivery of health and dental care, additional studies are needed on specific mechanisms effective in achieving such rate reductions. Although it can be argued that the NTDC ED/PO visit rate of 4.3% is fairly low, this rate is equivalent to one in 25 Medicaid enrollees with NTDC visits to EDs/POs. Further research is warranted regarding whether such NTDC ED/PO visits can be reduced by interventions such as targeted patient education about use of dental offices for NTDCs, and increasing Medicaid reimbursement rates to dentists for NTDC visits and regular dental care.

What practical steps might health professionals and policymakers take to reduce NTDC visits to ED/POs? One potential remedy might be greater attention to developing and implementing programs targeting expansion of the dental workforce and dental homes in minority and DHPSA communities. This could include establishing oral health triage centers with expanded hours within primary care practices, especially in inner-city communities with the greatest unmet dental care needs. These centers could be staffed by expanded-duty auxiliary dental personnel supervised by dentists. Another measure is to provide tax benefits or start-up funds to dentists willing to set-up practices in underserved communities with high unmet dental needs. Additionally, the Department of Health and Family Services should establish Medicaid dental outreach hotlines to link enrollees with a dental home in their community. These opportunities allow for patients, health professionals, and policymakers to work together to improve access to dental care on a system-wide basis. Finally, public health agencies could explore the use of social marketing tools in teaching Medicaid enrollees the importance of seeking care for NTDC in dental offices, and not in EDs or POs.

Limitations

Certain study limitations should be noted. We examined only Wisconsin Medicaid-enrolled patients, so the results may not necessarily pertain to other states. Nevertheless, we believe that the study findings may generalize to other states that cover adults for dental conditions, because, like many other states, Wisconsin has a racially/ethnically diverse population that includes both urban and rural poor. We used Medicaid claims data, which can be subject to coding errors, multiple sites of residence, multiple visits, inconsistently recorded provider information, and missing data caused by each of these factors. Of the original 1,317,811 claims considered for the analyses, there were 320,021 dental office visit exclusions and 386 ED/PO exclusions due to missing data or multiple claims for a single visit; this must also be viewed as a potential limitation, as inclusion of these visits (were one able to obtain this missing information) might have yielded different findings. In addition, we used DHPSA designation as a proxy for access to care. A better measure might be the availability of dentists accepting Medicaid in the patients’ coverage area; additional research is needed to examine NTDC visits to EDs and POs using this measure. Another limitation is that the analyses could not account for the potentially clustered nature of the data. An individual level analysis, accounting for the correlation between visits made by the same individual, was not possible, because enrollment data were only available in an aggregate form within each county. Therefore, it was not possible to track enrollment of each individual from month to month. This limitation has the potential to underestimate standard errors and to lead to an overstatement of statistical significance, and caution must be exercised in interpreting results that have a lower limit of the 95% confidence interval that is close to the null value.

CONCLUSIONS

Among those enrolled in Medicaid, Native Americans, those residing in entire DHPSAs, and adults have significantly higher risks of NTDC visits to EDs and POs. African-Americans are at increased risk of ED visits, and other races/ethnicities have a greater risk of PO visits for NTDCs. Reductions in Medicaid visits to EDs and POs and the associated costs might be achieved by improving dental care access and employing educational strategies targeted at certain minority groups, DHPSA residents, and adults.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Ebert for helping us with accessing the database. We are very grateful to the anonymous reviewers, whose helpful comments improved the quality of the manuscript. Dr. Okunseri was supported in part by an NIH K30 grant to the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Footnotes

Presented in part as a platform presentation at the annual meeting of the International Association for Dental Research, June, 28, 2006, in Brisbane, Australia.

References

- 1.Department of Health and Human Services. A Medicaid information source. Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2005. [Access verified 2/13/08]. Medicaid at-a-Glance: 2005. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MedicaidGenInfo/downloads/MedicaidAtAGlance2005.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Chartbook 2000. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Care Financing Administration; 2000. [Access verified 2/13/08]. A profile of Medicaid. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/TheChartSeries/downloads/2Tchartbk.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellis ER, Smith VK, Rousseau DA. Medicaid enrollment in 50 states, June 2004 data update. Washington, DC: The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burt CW, McCaig LF. Trends in hospital emergency department utilization: United states 1992–99. advance data from vital and health statistics. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2001. Series 13, No. 150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman P, Irons R, Nicholl J. Will alternative immediate care services reduce demands for non-urgent treatment at accident and emergency? Emerg Med J. 2001;18:482–7. doi: 10.1136/emj.18.6.482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis C, Lynch H, Johnston B. Dental complaints in emergency departments: A national perspective. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:93–9. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burt CW, Schappert SM. Ambulatory care visits to physician offices, hospital outpatient departments, and emergency departments: United states, 1999–2000. Vital Health Stat. 2004:13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham DB, Webb MD, Seale NS. Pediatric emergency room visits for nontraumatic dental disease. Pediatr Dent. 2000;22:134–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oral health in America: A report of the surgeon general. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institute of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.General Accounting Office. United States General Accounting Office (GAO), Report to Congressional Requester. Washington, DC: Apr, 2000. [Access verified 02/14/2008]. Oral health: Dental disease is a chronic problem among low-income populations; p. 44. GAO/HEHS-00-72. Available at: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/he00072.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewin ME, Altman S, editors. America’s health care safety net: Intact but endangered. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erin N. Dental care for Medicaid-enrolled children. American Public Human Services Association. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Care Financing Administration; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen LA, Manski RJ, Magder LS, Mullins CD. Dental visits to hospital emergency departments by adults receiving Medicaid: Assessing their use. JADA. 2002;133:715–24. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waldrop RD, Ho B, Reed S. Increasing frequency of dental patients in the urban ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:687–9. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2000.7333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheller B, Williams BJ, Lombardi SM. Diagnosis and treatment of dental caries-related emergencies in a children’s hospital. Pediatr Dent. 1997;19:470–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ICD-9CM: International classification of diseases, 9th revision, clinical modifications. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1989. Publication No. (PHS) 91-1260. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bureau of Health Professions. [Accessed 09/07/2006];Health professional shortage area dental designation criteria. Available at: http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/shortage/hpsacritdental.htm.

- 18.Orlans J, Mertz E, Grumbach K. Revising Dental health shortage area methodology: A critical review. San Francisco: UCSF Center for Health Professions CA; Oct, 2002. [Access verified 02/14/2008]. Available at: http://futurehealth.ucsf.edu/cchws/DHPSA.html. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Overview of children’s oral health in Wisconsin, youth oral health data collection report. Oral Health Program Division of Public Health, Wisconsin Department of Health and Family Services; 2001–02. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Economic Research Service, US Department of Agriculture. [Accessed 5/25/07];Measuring rurality: Urban influence codes. Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/Rurality/urbaninf/

- 21.Agostini FG, Flaitz CM, Hicks MJ. Dental emergencies in a university-based pediatric dentistry postgraduate outpatient clinic: A retrospective study. ASDC J Dent Child. 2001;68:316–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ladrillo TE, Hobdell MH, Caviness AC. Increasing prevalence of emergency department visits for pediatric dental care, 1997–2001. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:379–85. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen LA, Manski RJ, Magder LS, Mullins CD. A Medicaid population’s use of physicians’ offices for dental problems. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1297–301. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen LA, Manski RJ. Visits to non-dentist health care providers for dental problems. Fam Med. 2006;38:556–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flores G, Tomany-Korman SC. Racial and ethnic disparities in medical and dental health, access to care, and use of services in US Children. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e286–e298. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dye BA, Shenkin JD, Ogden CL, Marshall TA, Levy SM, Kanellis MJ. The relationship between healthful eating practices and dental caries in children aged 2–5 years in the United States, 1988–1994. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:55–66. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watson MR, Brown LJ. The oral health of U.S. Hispanics: Evaluating their needs and their use of dental services. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995;126:789–95. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1995.0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vargas CM, Crall JJ, Schneider DA. Sociodemographic distribution of pediatric dental caries: NHANES III, 1988–1994. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:1229–38. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gift HC, Reisine ST, Larach DC. The social impact of dental problems and visits. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:1663–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.12.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.US Department of Health and Human Services. National call to action to promote oral health. Rockville, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; 2003. NIH Publication No. 03-5303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Center for Health Statistics Health. United States, 2006 With Chartbook on Trends in the Health of Americans. Hyattesville, MD: 2006. [Access verified 2/14/08]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus06.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abe-Kim J, Takeuchi DT, Hong S, et al. Use of mental health-related services among immigrant and US-born Asian Americans: Results from the national Latino and Asian American study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:91–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aroian KJ, Wu B, Tran TV. Health care and social service use among Chinese immigrant elders. Res Nurs Health. 2005;28:95–105. doi: 10.1002/nur.20069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu SM, Huang ZJ, Singh GK. Health status and health services utilization among US Chinese, Asian Indian, Filipino, and other Asian/Pacific islander children. Pediatrics. 2004;113:101–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Machlin SR. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Statistical Brief #111. Bethesda, Md: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006. [Accessed April 3, 2008]. Expenses for a hospital emergency room visit, 2003. Available at: “ http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st111/stat111.pdf”. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wisconsin Department of Health and Family Services. Dental maximum allowable fee schedule. Madison, Wi: Wisconsin Department of Health and Family Services; 2008. [Accessed April 3, 2008]. Available at: “ http://dhfs.wisconsin.gov/medicaid4/maxfees/pdf/maxfee08_dental-standard.pdf”. [Google Scholar]