Abstract

Background

Apoptosis is thought to play a role in infarction induced ventricular remodeling. Apoptosis Repressor with Caspase Recruitment Domain (ARC) has been shown to limit cardiomyocytes apoptosis; however, its role in the pathogenesis of heart failure is not established. This study examines the regional and temporal relationships of apoptosis, ARC and remodeling.

Methods

Myocardium was harvested from the infarct borderzone and remote regions of the left ventricle (LV) at two (n=8), eight (n=6) and 32 (n=5) weeks after MI. Activated ARC was compared to myocardial apoptosis in each region at each time. Both were then compared to the progression of remodeling.

Results

LV systolic volume increased by a factor 1.56 ± 0.06 and 2.09 ± 0.07 at two and eight weeks, respectively then stabilized by 32 weeks (2.08 ± 0.18). Activated ARC was elevated at two weeks, diminished at eight weeks and increased again at 32 weeks in both regions. Apoptosis was elevated at two weeks, and further increased at eight weeks. By 32 weeks apoptosis had diminished significantly.

Conclusions

In a large animal infarction model, remodeling varied directly with the degree of apoptosis and inversely with ARC activation suggesting that ARC acts as a natural regulatory phenomenon that limits apoptosis induced ventricular remodeling.

Keywords: cardiomyopathy, apoptosis, heart failure, remodeling, myocardial infarction

Introduction

Infarction induced ventricular remodeling is associated with progressive ventricular enlargement, contractile dysfunction and symptomatic heart failure (HF). In many cases this dilated cardiomyopathy evolves over time without subsequent infarctions. The pathogenesis of this phenomenon is not well understood, but evidence suggests that progressive myocardial cell apoptosis, independent of further ischemia and secondary to increased regional wall strains plays an important role.1, 2,3,4 Previous work using isolated myocytes support the hypothesis that chronic increases in strain act as a stimulus for apoptosis and progressive contractile dysfunction.5, 6

Apoptosis is an orderly regulated process and, therefore, may provide a number of early therapeutic targets to limit adverse post MI ventricular remodeling and heart failure. 7,8 Remodeling has been demonstrated to affect the ventricle in a regional and time dependent manner.9, 10 Therefore, to identify potential therapeutic targets within the apoptotic cascade, it is important to understand the temporal and regional variation in myocyte apoptosis and its naturally occurring inhibitors as HF ensues. To accomplish this we studied the progression of myocyte apoptosis as well as the expression and activation of Apoptosis Repressor with Caspase Recruitment Domain (ARC) in a clinically relevant large animal model of infarction induced remodeling.

ARC has been shown to be constitutively expressed in myocardium and acts to inhibit both the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways.11, 12 Additionally, it has been shown in a recent study that ARC deficient mice are more susceptible to myocyte apoptosis stimulated by the mechanical stress of aortic banding as well as reperfusion injury.13 These studies provide evidence of the cardioprotective role of ARC in HF and suggest that its manipulation may represent a novel therapeutic strategy.

Materials and Methods

Ovine Infarct Model

Twenty two Dorset sheep were induced with 15 mg/kg of intravenous (IV) thiopental sodium, intubated, anesthetized with isoflurane (2%), and ventilated with oxygen. Animals were treated in compliance with National Institutes of Health Publication No. 85-23 as revised in 1996.

All animals underwent a left thoracotomy. The left anterior descending and second diagonal coronary arteries were ligated (40% of the distance from the apex to base) in 19 animals to produce an anteroapical infarction of 22±3% of the left ventricular (LV) mass.14 Infarct was confirmed by myocardial color change and confirmation of wall motion abnormality by echocardiography. This infarction serves as a strong stimulus for remodeling, causing progressive ventricular dilatation and dysfunction.

Quantitative two-dimensional echocardiography, a widely accepted and well validated method for assessing ventricular remodeling in patients15 as well as animal models16, was used to assess the progression of ventricular enlargement. Echocardiographic images were obtained and used to quantify left ventricular end systolic volume and end diastolic volumes before infarction, 30 minutes post infarction and just prior to euthanasia, as described previously.16 Systolic and diastolic LV volumes are reported normalized to pre infarction values (NESV and NEDV).

Animals were euthanized at two weeks (n=8), eight weeks (n=6) and 32 weeks (n=5) after infarction. Hearts were harvested after arrest with a cold hyperkalemic solution. Transmural (endocardial to epicardial) punch biopsies were taken from borderzone (directly adjacent to but not including scar) and remote (base of the heart) regions. Specimens were frozen and stored at −80°C.

Samples from each region were placed in formalin, dehydrated in ethanol and wax embedded. Tissue was also preserved in electron microscopy fixative for 24 hours at 4 °C.

Normal hearts (uninfarcted) were harvested from 3 animals and biopsies taken from similar areas of the LV to serve as controls.

Assessment of Apoptosis

To evaluate the relationship of myocyte apoptosis and post infarction ventricular remodeling, biochemical and morphological characteristics were assessed.

Immunoblot Analysis

Immunoblotting was used to assess the levels of active caspase-3, ARC and phosphorylated ARC.

Frozen tissue specimens were lysed in buffer (1% Triton X-100, 10 mmol/L imidazole, 1 mmol/L KCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 5 mmol/L MgCl) containing protease (Roche Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) and phosphatase inhibitors (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) for 30 min at 4 °C. The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant fraction removed and stored at −80 °C.

Forty micrograms of total protein were separated on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), blocked in 5% non-fat dried milk in PBST (80 mmol/L Na2HPO4, 1 mmol/L NaCl, and 0.05% Tween-20), incubated in different primary and secondary antibodies, and detected using a chemiluminescent immunodetection system (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Primary antibodies included active caspase-3 (1:200) (R280, Merck Frosst Laboratory; Montreal) ARC (1:1000) (#160737, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) and phosphorylated ARC (1:100) (gift from Rüdiger von Harsdorf). Secondary antibodies were purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ). To ensure equal loading of protein lysates, a Ponceau stain was used (24580, Pierce Biotechnology, Inc; Rockford, IL). Optical density values were quantified using Image Pro Plus, version 4.5 (Silver Spring, MD).

TUNEL Staining

CardioTACS™ In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (R&D Systems Inc, #TA5353; Minneapolis, MN) was used to detect DNA fragmentation in tissue sections. For each sample, two slides were stained. From each slide, 16 10X fields of view were digitized for analysis. TUNEL positive nuclei and total nuclei were then counted for each image, tallied for each slide, and averaged for each sample.

BAX Immunostaining

Tissue sections were treated in boiling Target Retrieval Solution (DAKO, S1699; Carpinteria, CA) and immunostained for BAX (1:100) (Upstate, 06-499; Charlottesville, VA). A histochemical score (0 to 3) that incorporates intensity of staining and percentage of staining was used to assess tissue sections.

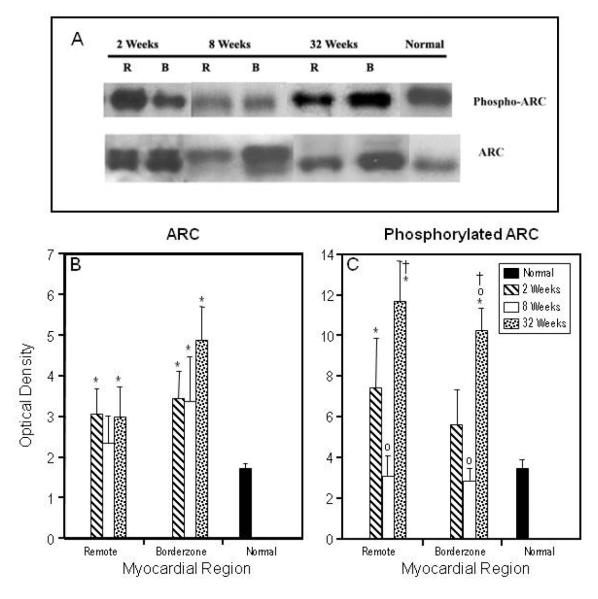

Transmission Electron Microscopy Imaging

Electron Microscopy (EM) was used to assess morphologic changes consistent with apoptosis in the nucleus, mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum of cells. Tissue samples were imaged on a Jeol-1010 transmission electron microscope (Jeol Ltd., Akishima, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance was used to assess the overall regional and temporal effects for all continuous dependent variables. When overall effects were identified as significant, individual comparisons were made with Student’s t-test with Bonferroni correction. Data is present as means ± SEM

For ordinal data the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess the overall regional and temporal effects. Significant individual comparisons were subsequently determined using the Mann-Whitney test. Data is present as the median and its relationship to the interquartile range.

Results

Assessment of Remodeling

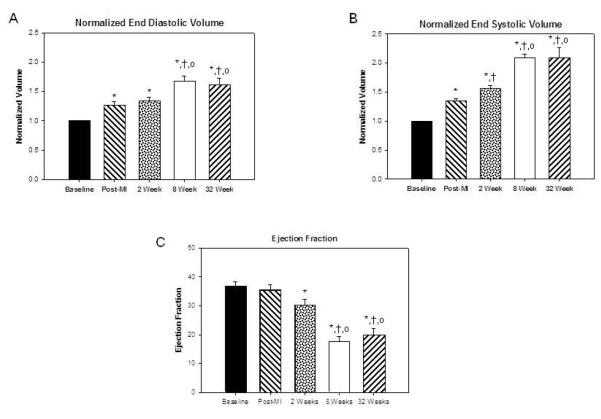

Immediately post infarction NEDV and NESV increased to 1.26 ± 0.06 and 1.35 ± 0.04 respectively. After two weeks NEDV increased to1.33 ± 0.06 and NESV increased to 1.56 ± 0.05. The most rapid increase in ventricular size occurred between two and eight weeks after infarction. During this time NEDV increased to 1.67 ± 0.09 and NESV increased to 2.09 ± 0.07. There was no significant increase in NEDV and NESV between eight and 32 weeks (1.60 ± 0.12 and 2.08 ± 0.19, respectively). Differences in NEDV and NESV over time are presented in figure 1A and 1B. Left ventricular ejection fraction (figure 1C) also decreased most dramatically between two and eight weeks (32.2% ± 2.0% to 17.5% ± 1.9% p<0.001) but remained stable from eight to 32 weeks (19.7 ± 2.3%)

Figure 1. Echocardiographic measurements of ventricular volumes.

Panels A and B present changes in normalized diastolic and systolic volumes during remodeling. Data are presented as Mean ± SEM. Note the increase in ventricular size 30 minutes post infarction. Ventricular enlargement was relatively mild during the first two weeks when compared with the 8 week post infarction volumes. Ventricular volumes remained stable after 8 weeks. Panel C demonstrates the change in LV ejection fraction. Ejection fraction dropped most dramatically between 2 and 8 weeks post infarction but remained stable at 32 weeks. (*) Significant changes from pre infarction (p ≤ 0.05); (†) significant changes compared to 30 minutes; (○ ) significant changes when compared to two weeks. Panel D shows representative end systolic long axis echocardiographic images of a sheep LV at baseline, two weeks, eight weeks and 32 weeks post infarction.

Serial end systolic echocardiographic images of a representative animal followed for 32 weeks after infarction are shown in figure 1D. These images represent standard long axis views of the LV. In each view the apex of the heart is oriented toward the left upper corner while the left atrium, mitral valve and outflow tract are seen in the lower right corner. The images demonstrate progressive LV enlargement during the first 8 weeks after infarciton. The image of the 8 week ventricle and the 32 week ventricle are similarly sized.

Assessment of Apoptosis

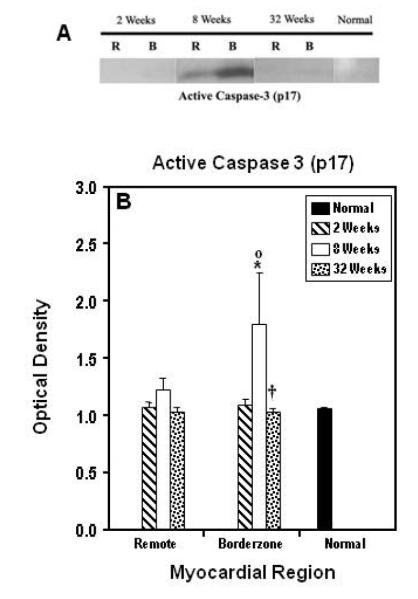

Immunoblot Analysis

Figure 2A illustrates a representative immunoblot of all regions at all time points post infarction for active Caspase 3 (p17). Figure 2B displays changes in active caspase 3 levels which were significantly elevated in the borderzone (p< 0.001) at eight weeks and returned to normal by 32 weeks after infarction. A similar trend was seen to a lesser extent in the remote region.

Figure 2.

Panel A shows a representative immunoblot for active caspase 3. Panel displays the average data for all regions (B= borderzone, R=remote, N=normal myocardium) at all time points. Data are presented as Mean ± SEM. Significant changes from normal myocardium (*) (p ≤ 0.05); significant changes when compared to two weeks (○) and eight weeks (†) within regions. Note that the early elevation (two to eight weeks) in active caspase 3 and how this change normalized at 32 weeks post infarction.

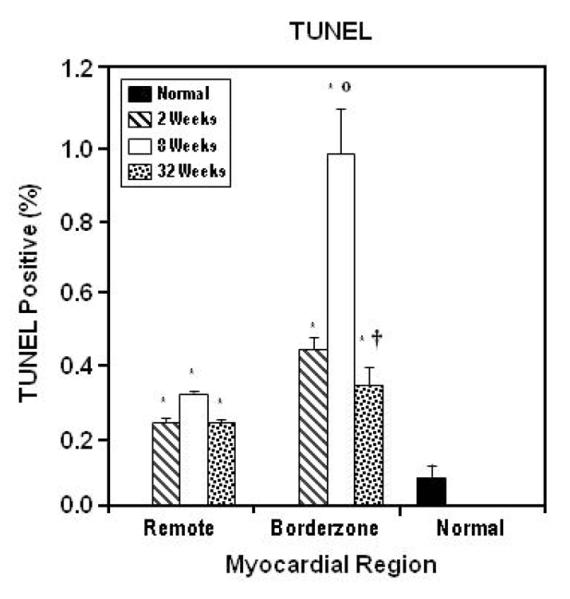

TUNEL Staining

In both regions the percentage of TUNEL positive nuclei was greater than normal (0.08% ± 0.048%) at all time points. The percentage of TUNEL positive nuclei was maximally elevated at eight weeks in the borderzone (0.95% ± 0.12%) and remote (0.30% ± 0.01%) regions (figure 3). In the borderzone the eight week staining was significantly greater than at two weeks (p < 0.001). A similar trend was also present in the remote region (p < 0.10). At 32 weeks after infarction, TUNEL staining had returned to two week levels in both regions (remote, 0.23% ± 0.01% and borderzone 0.36% ± 0.02%).

Figure 3. TUNEL Immunostain.

In both borderzone and remote regions the percentage of TUNEL positive nuclei was significantly greater at all time points (*). The increase in TUNEL positive nuclei reaches its maximum at eight weeks and returns toward normal at 32 weeks in all regions. Statistically significant difference from two weeks is indicated by (○). Significant difference from eight weeks is indicated by (†). Data are presented as Mean ± SEM.

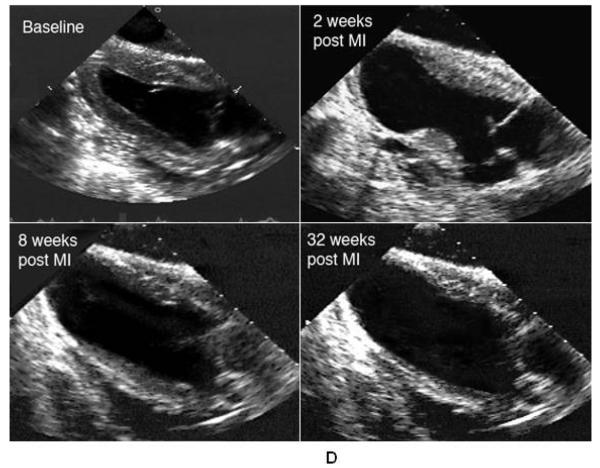

Transmission Electron Microscopy Imaging

EM imaging of the borderzone regions at two and eight weeks demonstrated structural signs of myocyte apoptosis. These changes included marked dilatation of both the t-tubule system and endoplasmic reticulum. Many of the mitochondria in affected myocytes were abnormal. These abnormalities included: swelling, blurring of cristae, heterogeneous morphology and frank disruption (figure 4A). Though less pronounced than the mitochondrial aberrations, nuclear changes consistent with apoptosis were also seen in myocytes in the borderzone at two and eight weeks. Nuclei most commonly demonstrated chromatin condensation but bizarre nuclear morphology like that demonstrated in figure 4B were also seen in all borderzone samples at two and eight weeks. All apoptotic changes seen in the borderzone were present to a lesser extent in the remote region at two and eight weeks. At 32 weeks, signs of apoptosis were still present in the borderzone and remote regions but to a lesser extent than at earlier time points.

Figure 4. Ultrastructural changes of apoptotic myocytes.

EM images demonstrating mitochondrial disruption (25,000X) (panel A) and bizarre myocyte nuclear disruption (15,500X) (panel B) within the borderzone at eight weeks post infarction.

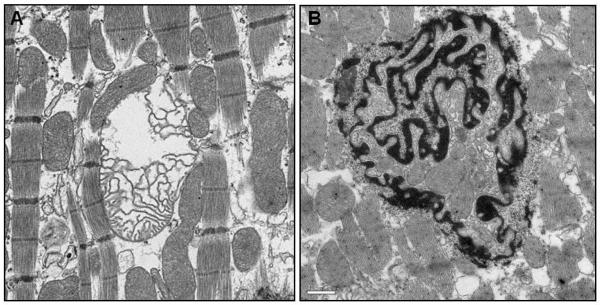

Assessment of ARC Levels and Activity

Total ARC was elevated in the borderzone (p < 0.001) at all time points post infarction. In the remote myocardium, it was elevated at two (p < 0.001) and 32 weeks (p < 0.003) (figure 5A, B).

Figure 5. Remodeling induced changes in ARC expression and activation.

Representative immunoblots demonstrating changes in total ARC and activated ARC at specified times during the post infarction remodeling process (panel A). For each of these animals, samples were taken from the borderzone (B) and remote (R) regions of the left ventricle. Graphical representation of immunoblot optical density for total ARC (panel B) and phosphorylated ARC (panel C) in all myocardial regions at all time points post infarction. Data are presented as Mean ± SEM. (*) Significant changes from normal myocardium (p ≤ 0.05); significant changes when compared to two weeks (○), and eight weeks (†) within regions. In the borderzone and remote regions ARC activation is elevated at two weeks, diminishes at eight weeks and subsequently increases dramatically at 32 weeks.

Phosphorylated ARC, the active form of the protein17, was elevated in remote and borderzone myocardium at two (p < 0.01 and 0.08 respectively) and 32 weeks (p < 0.0005 and 0.0001 respectively) after infarction (figure 5C). Phosphorylated ARC was not found to be elevated at eight weeks in either of these regions.

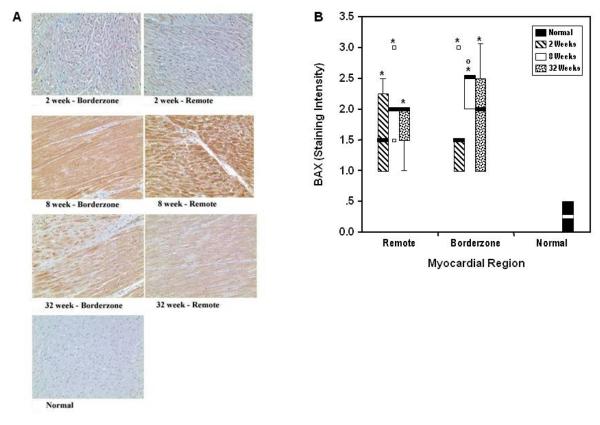

Activated BAX immunostaining

In both regions, activated BAX staining was elevated at two weeks post infarction, reached a peak at eight weeks, and returned toward normal levels at 32 weeks (figure 6). Since activated ARC binds with and blocks BAX conformational activation this trend is consistent with the reported temporal changes in ARC activation and apoptosis.18

Figure 6. BAX Immunostain.

Panel A shows representative sections (20X) for each myocardial region at each time point. BAX staining was elevated above normal in all regions at all time points. In all regions the most intense staining was found at eight weeks post infarction. Panel B illustrates box and whisker plots summarizing ordinal ranking of BAX staining intensity. For each region at each time point the bold lines represent the median value, the box defines the interquartile range with its upper and lower ends representing the lower limits of the first and third quartile, respectively. The whiskers are lines that extend from the box to the highest and lowest values outside the box but within 1.5 times the interquartile range. The small squares (□) represent values farther than 1.5 times the interquartile range from the ends of the box. Significant changes from normal myocardium (*) (p ≤ 0.05); significant changes when compared to two weeks (○) and eight weeks within regions.

Discussion

Apoptosis and Remodeling

The magnitude to which apoptosis contributes to ventricular remodeling, the associated myopathic process and the development of symptomatic heart failure has been difficult to establish. The initially reported rates of myocyte apoptosis in patients with advanced cardiomyopathy were low and raised concerns about the actual role of apoptosis in the genesis of heart failure.2, 19, 20 Subsequent studies reported much higher apoptotic rates that seemed incompatible with the known time course over which heart failure develops after a MI.21 Much of the inconsistency highlighted by these studies likely results from the inherently uncontrolled nature of experiments that use human myocardial tissue that becomes available as a result of death or cardiac transplantation. Such human specimens are harvested from various regions within the heart without regard for location or size of the infarct, at different time points after the onset of remodeling and from hearts responding to different remodeling stimuli. This study was designed to limit these variables and to isolate the effects of time and myocardial region on the degree of apoptosis as heart failure develops.

We serially assessed the long-term temporal and regional progression of myocardial apoptosis as well as global changes in ventricular size in a large animal model of infarction induced ventricular remodeling. The progressive increase in regional myocardial strains and decrement in regional function in this model have been described and shown to be independent of ischemia.6, 16 The ventricle progressively dilates as strain induced myopathy and resulting contractile dysfunction spreads from infarct region to the borderzone and ultimately remote myocardium over eight weeks.6

Myocardial apoptosis was evident throughout the heart and most intense in the borderzone region adjacent to the infarct. All indices of apoptosis increase between two and eight weeks after infarction and subsequently decreased at the 32 week time point. This time course for apoptotic activity corresponded with the extent of global remodeling as assessed by echocardiography, lending quantitative support to clinical studies that have implied that the two phenomena are causally linked. These data support the conclusion that, for apical infarcts of moderate size, the stimulus for apoptosis is very intense during the initial two months after infarction. Previous work in our laboratory using this infarct model has demonstrated that infarct expansion (stretching) is most pronounced during this time period after the MI.6 To explain the mechanism by which an infarction initiates the myopathic process that occurs along with remodeling, Jackson9,22 and Ratcliffe16 have hypothesized that infarct expansion leads to geometrical distortions in borderzone myocardium which increases strain. They further propose that strain initiates a regionally progressive myocyte apoptosis that ultimately results in a “nonischemic” extension of the infarct. The data presented in this study support this hypothesis.

ARC Inhibition of Apoptosis and Remodeling

ARC is expressed diffusely but is enriched in long-lived terminally differentiated cells such as cardiac and skeletal muscle as well as neurons.8,23 It requires phosphorylation for activation17 and unlike most other endogenous apoptosis inhibitors antagonizes both central apoptotic pathways.

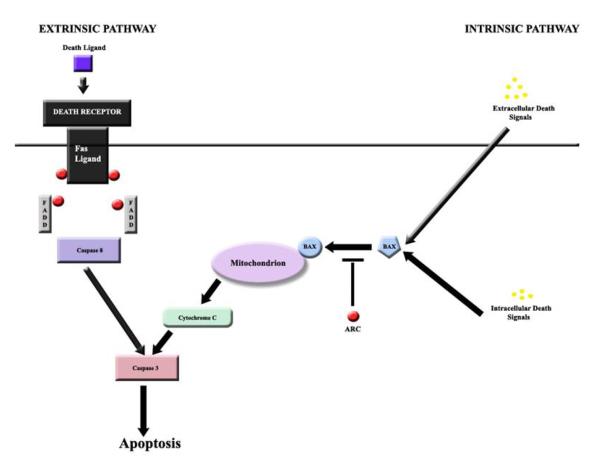

Nam and colleagues have elucidated the mechanism by which ARC inhibits both the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways.7 They demonstrated that a direct interaction between the CARD (caspase recruitment domain) component of ARC and the death domain components of Fas and FADD were essential to inhibiting the extrinsic pathway. They also showed that a CARD-non-death-fold interaction with BAX resulted in inhibition of the extrinsic pathway. ARC’s binding to Fas and FADD is heterotypic and inhibits assembly of the death-inducing signaling complex, while ARC’s binding to BAX blocks BAX’s conformational activation and translocation to the mitochondria (figure 7).18

Figure 7. Extrinsic and Intrinsic Apoptotic Pathways.

The extrinsic pathway is blocked by ARC’s ability to bind heterotrophically to Fas and FADD and prevent assembly of the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC). Subsequently, activation of caspase-8 is inhibited and apoptosis is prevented. ARC blocks the intrinsic pathway with its ability to bind to BAX and block BAX’s conformational activation and translocation to the mitochondria.

A recent study found ARC deficient mice to be more sensitive to myocyte apoptosis associated with mechanical stress and reperfusion injury. Based on these findings the authors propose the manipulation of ARC levels as a potential therapeutic strategy for treating heart failure.12 While evidence is building to support this concept,24 the proper implementation of such strategies require a better understanding of ARC expression during post infarction remodeling. This was a primary goal of the current study.

This is the first report regarding myocardial ARC expression and its activation during infarction induced ventricular remodeling. The time course of ARC activation was found to be complex. Activated ARC was increased two weeks after infarction but decreased to pre infarction levels at eight weeks as apoptosis and LV volumes peaked. By 32 weeks after the MI, activated ARC levels became dramatically elevated in the BZ and remote regions as LV size stabilized and apoptosis decreased. As expected from the work of Nam et al,7 staining for activated BAX, varied inversely with time when compared with activated ARC levels. While activated BAX was elevated at all time points it was maximally elevated at 8 weeks when ARC levels were lowest and decreased closer to normal levels at 32 weeks when activated ARC levels were highest. Since ARC binds to BAX to prevent its transformation to the activated form, the finding that active BAX immunostaining is lowest when activated ARC levels are highest supports ARC’s anti-apoptotic effect in this model. Also, this finding taken in conjunction with the EM assessment of mitochondrial disruption makes a compelling case for ARC’s influence on the intrinsic apoptotic pathway during the remodeling process.

Our data demonstrate that ventricular enlargement varies directly with the extent of myocardial apoptosis and inversely with ARC activation. These results suggest ARC may be a natural counter regulatory phenomenon that limits myocyte apoptosis and remodeling.

Implications and Limitations

The concept of early therapeutic interference with pro-apoptotic stimuli to prevent heart failure is extremely attractive. However, the development of a realistic strategy to accomplish such a goal has suffered from a lack of understanding of the regional and temporal changes in the prevalence and regulation of myocyte apoptosis in remodeling myocardium. This study helps to address some of these important issues.

To date, much work has focused on caspase inhibition with some success in small animal heart failure models. 25,26 The lack of organ specificity may hinder the long term effectiveness and feasibility of such a therapeutic approach. Identification and characterization of a cardiomyocyte-specific endogenous anti-apoptotic factor, such as ARC, represents a promising therapeutic target. While the mechanisms responsible for the variations in ARC levels described in this study remain to be elucidated, the fact that ARC levels reach a nadir during the period of maximal structural remodeling and myocyte apoptosis suggest that ARC augmentation during this time period may be potentially beneficial. The experiments presented here, while only observational, are a first step; much more work will be required before augmentation of ARC activation can be realistically proposed as a heart failure strategy. Optimally, ventricular remodeling as assessed by state of the art imaging (echocardiography, MRI, CT scan, nuclear imaging) should be correlated with apoptosis and ARC levels to see if subtle early changes in LV geometry can be used to predict diminishing ARC levels and increases in apoptosis. While such work cannot be performed using human studies, the ovine model, which mimics the human disease well, is a powerful tool to do so.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD) grants HL63954, HL76560, HL71137 and grants from the W.W. Smith Charitable Trust (West Conshohocken, PA) and the Mary L. Smith Charitable Trust (West Conshohocken, PA).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Narula J, Haider N, Virmani R, et al. Apoptosis in myocytes in end-stage heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1182. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610173351603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olivetti G, Abbi R, Quaini F, Kajstura J, et al. Apoptosis in the failing human heart. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704173361603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldi A, Abbate A, Bussani R, et al. Apoptosis and post-infarction left ventricular remodeling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:165. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Narula J, Arbustini E, Chandrashekhar Y, Schwaiger M. Apoptosis and the systolic dysfunction in congestive heart failure. Cardiol Clin. 2001;19:113. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8651(05)70198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng W, Li B, Kajstura J, et al. Stretch induced programmed myocyte cell death. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2247. doi: 10.1172/JCI118280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pimentel DR, Amin JK, Xiao L, et al. Reactive oxygen species mediate amplitude-dependent hypertrophic and apoptotic responses to mechanical stretch in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2001;89:453. doi: 10.1161/hh1701.096615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nam YJ, Mani K, Ashton AW, et al. Inhibition of both the extrinsic and intrinsic death pathways through nonhomotypic death-fold interactions. Mol Cell. 2004;15:901. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danial NN, Korsmeyer SJ. Cell death: critical control points. Cell. 2004;116:205. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson BM, Gorman JH, 3rd, Moainie S, et al. Extension of Borderzone Myocardium in Postinfarction Dilated Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1160. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E. Ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction: experimental observations and clinical implications. Circulation. 1990;81:1161. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.4.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ekhterae D, Lin Z, Lundberg MS, et al. ARC inhibits cytochrome c release from mitochondria and protects against hypoxia-induced apoptosis in heart-derived H9c2 cells. Circ Res. 1999;85:e70. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.12.e70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koseki T, Inohara N, Chen S, Nunez G. ARC, an inhibitor of apoptosis expressed in skeletal muscle and heart that interacts selectively with caspases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donath S, Li P, Willenbockel C, et al. Apoptosis repressor with caspase recruitment domain is required for cardioprotection in response to biomechanical and ischemic stress. Circulation. 2006;113:1203. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.576785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Markovitz LJ, Savage EB, Ratcliffe MB, et al. Large animal model of left ventricular aneurysm. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989;48:838. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(89)90682-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sutton MG, Pfeffer MA, Plappert T, et al. Quantitative two-dimensional echocardiographic measurements are major predictors of adverse cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction. The protective effects of captopril. Circulation. 1994;89:68. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelley ST, Malekan R, Gorman JH, 3rd, et al. Restraining infarct expansion preserves left ventricular geometry and function after acute anteroapical infarction. Circulation. 1999;99:135. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li PF, Li J, Muller EC, et al. Phosphorylation by protein kinase CK2: A signaling switch for the Caspase-inhibiting protein ARC. Mol Cell. 2002;10:247. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00600-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gustafsson AB, Tsai JG, Logue SE, et al. Apoptosis with Caspase recruitment domain protects against cell death by interfering with Bax activation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400695200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saraste A, Pulkki K, Kallajoki M, et al. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis and progression of heart failure to transplantation. Eur J Clin Invest. 1999;29:380. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1999.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guerra S, Leri A, Wang X, et al. Myocyte death in the failing human heart is gender dependent. Circ Res. 1999;85:856. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.9.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharov VG, Sabbah HN, Ali AS, et al. Abnormalities of cardiocytes in regions bordering fibrous scars of dogs with heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 1997;60:273. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(97)00117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson BM, Gorman JH, III, Salgo I, et al. Altered borderzone geometry increases wall stress after anteroapical myocardial infarction: A contrast echocardiographic assessment. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:H475. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00360.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geertman R, McMahon A, Sabban EL. Cloning and characterization of cDNAs for novel proteins with glutamic acid-proline dipeptide tandem repeats. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1306:147. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(96)00036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chatterjee S, Bish LT, Jayasankar V, et al. Blocking the development of postischemic cardiomyopathy with viral gene transfer of the apoptosis repressor with caspase recruitment domain. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125:1461. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(02)73229-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neviere R, Fauvel H, Chopin C, et al. Caspase inhibition prevents cardiac dysfunction and heart apoptosis in a rat model of sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:218. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2003109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayakawa Y, Chandra M, Miao W, et al. Inhibition of cardiac myocyte apoptosis improves cardiac function and abolishes mortality in the peripartum cardiomyopathy of Gαq transgenic mice. Circulation. 2003;108:3036. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000101920.72665.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]