Abstract

CusCFBA is one of the metal efflux systems in Escherichia coli, which is highly specific for its substrates Cu(I) and Ag(I). It serves to protect the bacteria in environments that have lethal concentrations of these metals. The membrane fusion protein CusB is the periplasmic piece of CusCFBA, which has not been fully characterized by crystallography due to its extremely disordered N-terminal region. This region has both structural and functional importance as it has been experimentally proven to transfer the metal by itself from the metallochaperone CusF and to induce a structural change in the rest of CusB to increase Cu(I)/Ag(I) resistance. Understanding metal uptake from the periplasm is critical to gain an insight to the mechanism of the whole CusCFBA pump, which makes resolving a structure for the N-terminal region necessary as it contains the metal binding site. We ran extensive molecular dynamics simulations to reveal the structural and dynamic properties of both apo and Cu(I)-bound versions of the CusB N-terminal region. In contrast to its functional companion CusF, Cu(I)-binding to the N-terminal of CusB causes only a slight, local stabilization around the metal site. The trajectories were analyzed in detail revealing extensive structural disorder in both the apo and holo forms of the protein. CusB was further analyzed by breaking the protein up into three subdomains according to the extent of the observed disorder: the N- and C-terminal tails, the central beta strand motif, and the M21–M36 loop connecting the two metal-coordinating methionine residues. Most of the observed disorder was traced back to the tail regions leading us to hypothesize that the latter two subdomains (residues 13–45) may form a functionally competent metal binding domain as the tail regions appear to play no role in metal binding.

Keywords: CusB, CusCFBA, Cu(I)-transfer, metal transfer, copper resistance, metal homeostasis, intrinsically disordered proteins

Introduction

In most organisms, copper-binding enzymes are usually membrane-bound or found in the periplasm (1). E. coli is one of these: In E. coli the periplasm can contain significantly higher copper concentrations than the cytoplasm since copper is needed for periplasmic or inner membrane enzymes such as multi-copper oxidases, Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutases, or cytochrome c oxidase, the final enzyme of the respiratory chain (2). Still, periplasmic copper concentrations must be kept at low levels because Cu(I) can initiate the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) under aerobic conditions (2). This delicate balance is achieved through various metal-resistance systems against excess metal concentrations including the RND-type (resistance, nodulation, division) transporters, which are common defense mechanisms not only in E. coli but all Gram-negative bacteria. Thus, they play major roles in the intrinsic and acquired antibiotic resistance of Gram-negative bacteria by facilitating their survival in otherwise lethal concentrations of drugs and metal ions (3). They also aid in expelling bacterial products such as siderophores, peptides, and quorum-sensing signals (4, 5). Clearer insight into these efflux mechanisms is of significant importance considering how antibiotic resistant pathogens represent a growing threat to human health.

RND-type efflux systems consist of three fundamental components: an energy-requiring inner membrane protein (6), an outer membrane factor, and a periplasmic component (7). Proton-substrate antiporters of the RND protein superfamily serve as the inner membrane components and their exported substrate determines the subclass to which they belong. Accordingly, the inner membrane proteins ejecting heavy metals make up the heavy metal efflux subfamily and they are highly substrate-specific with the ability of differentiating even between the charge of the ions (6). The cytoplasm or the periplasm provide the substrates, depending on the properties of the particular efflux system and the substrate (8).

The CusCFBA efflux system in E. coli is responsible for extrusion of Cu(I) and Ag(I) and consists of CusA, the inner membrane proton/substrate antiporter of the heavy metal efflux-RND family, CusB, the periplasmic protein, and CusC, the outer membrane protein (9–11). The Cus system has an additional fourth component, CusF, which acts as a periplasmic Cu(I)/Ag(I) metallochaperone and is vital for maximal metal resistance (10, 12). The periplasmic protein CusB is a member of the membrane fusion protein (MFP) family (13). It is hypothesized to stabilize the tripartite intermembrane complex through its interactions with CusA and CusC which is similar to the role that AcrA plays in the well-characterized multidrug efflux pump AcrAB-TolC (14–17). Four domains were identified from the available crystal structures: the membrane proximal, beta-barrel, lipoyl, and alpha-helical domains. However, the most important part containing the three conserved metal binding Met residues could not be resolved with crystallographic techniques (14, 18). Mutation studies conducted on these three Met residues have resulted in the loss of metal resistance in vivo (19). Moreover, CusB and CusF interact temporarily in the presence of metal and have similar metal-binding affinities inferred from experimental findings where the metal in the medium gets distributed approximately equally between them when mixed in equimolar concentrations in vitro (19, 20). Direct metal transfer between these proteins has also been shown experimentally (21). The CusB-CusF interaction was captured by chemical cross-linking/mass spectrometry experiments which underlines the significance of the N-terminal region in terms of protein-protein interactions and metal transfer (22).

Recently the N-terminal region of CusB (CusB-NT) was experimentally found to exhibit metal transfer from CusF by itself, although not as effectively as the full-length CusB, which rules out the hypothesis that CusB acts simply as a metal chelator. It must be inducing a structural change in the rest of the chain which gives rise to higher resistance. This change was actually captured experimentally, implying conformational flexibility (23). Yet the retention of the metal transfer ability by truncated CusB encouraged us to examine this region by itself in order to unravel the dynamics and structure of this highly disordered entity. Being highly disordered in their N- and C-terminal regions is not an uncommon feature of membrane fusion proteins. The N- and C-termini of the multidrug efflux MFP’s MexA and MacA could not be crystallographically resolved either (24–26). These regions appear to be of flexible and dynamic nature as the observed disorder suggests.

Structural and dynamic properties of proteins can be probed simultaneously by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which make them especially useful for studying protein structure and folding. (27). Recent attempts to examine the folding pathways of several peptides including villin headpiece (28–37), bovine acyl-coenzyme A (38), Trp-cage (39–44), and Alzheimer amyloid beta 10–35 peptide (45) resulted in success suggesting this technique has the potential to provide molecular-level insights into the structure of CusB.

As stated above, the available crystal structures of the periplasmic protein CusB lack their N-termini. The absence of this very important piece hampers the ultimate modeling of the full metal efflux pump CusCFBA where metal uptake in the periplasm cannot be modeled. By determining a viable structural ensemble for CusB, whose members could transfer the metal from the open form of apo CusF, remains essential to reach our ultimate goal: simulating the entire metal extrusion process via CusCBA. Shedding light on this highly disordered domain would provide researchers with an ensemble of full model structures of CusB, which has been missing so far. Moreover, the insights gained would facilitate further insight on other disordered proteins (46).

In this manuscript, we examine the structural and dynamic changes of the N-terminal region of CusB upon Cu(I) binding by simulating the apo and holo CusB-NT using MD simulations and analyzing the sampled phase space in each case with various analysis tools.

Methods

We ran extensive MD simulations of 25 different initial models of the N-terminus region of CusB which were obtained with the protein structure prediction tools Quark (47), I-Tasser (48, 49), and Sparks-X (50). Quark is an ab inito protein folding and structure prediction algorithm, which is accessible through a web server. It constructs the 3D protein model from the amino acid sequence only with no global template information. Thus, it is useful for proteins without homologous templates. It was ranked as the leading server in free modeling in the CASP9 experiment. (47, 51, 52) The second folding server we used, I-Tasser, aims to predict protein structure and function by building 3D models based on multiple threading alignments and assembly simulations. The predicted models are then matched with the BioLiP protein function database (53). The latest CASP experiments ranked it as the number 1 server for protein structure prediction in addition to its first rank for function prediction in CASP9.(54) The third server we employed was Sparks-X, which is one of the best performers in the CASP9 experiment for single-method fold recognition. It is a template-based modeling algorithm which was established by weighted matching of multiple profiles and provides an improved scoring after taking into account errors in the predicted 1D structural properties (50). We refer to residues 29 through 79 of chain C in the crystal structure 3NE5 (18) as the N-terminus region of CusB. Residues 1 to 28 constitute the signaling region and were not included in this study. The residue numbering is reported after subtraction of the signaling peptide.

Both apo and Cu(I)-bound versions of the N-terminal region of CusB were simulated where all the protein and solvent atoms were treated explicitly. Each model system was solvated with the TIP3P triangulated water model (55) in a periodically replicated rectangular water box whose sides were at least 10 Å away from the solute atoms. The systems were neutralized by addition of Na+ ions and charged amino acids were modeled in the protonated states obtained with the H++ protonation state server at physiological pH (56). The apo models were run through an energy minimization protocol of seven stages involving the minimization of only the solvent atoms and the counter ions (stage 1), minimization of the hydrogen atoms (stage 2), minimization of the side chains by gradually decreasing the harmonic positional restraints acting on them (stages 3–6), and finally the energy minimization of the whole system with no positional restraints (stage 7). A total of 157,000 energy minimization steps were performed in total, 47,000 of which used the steepest descent protocol. (57) The remaining 110,000 steps utilized the conjugate gradient method for minimization. (57) A two-stage equilibration protocol followed: first, the systems were heated slowly from 0 to 300 K over 200 ps of MD within the canonical ensemble (NVT) by maintaining a weak harmonic restraint on the protein, and then they were simulated for 10 ns at 300 K to check for the stability of the peptide chains after removal of the harmonic restraints at a constant pressure of 1.0 bar for an isobaric, isothermal ensemble (NPT) using Langevin dynamics with a collision frequency of 1.0 ps−1 (58). Periodic boundary conditions were imposed on the systems during the calculation of non-bonded interactions at all minimization and equilibration stages while the lengths of the covalent bonds involving hydrogen were constrained and their interactions were omitted with the SHAKE algorithm while the systems were heated. (59) All the restraints on the systems were released before we started with the MD production runs with the apo models.

The metal coordination site of CusB was experimentally found to consist of three Met residues (M21, M36, and M38) aligned in almost an equilateral triangle through their sulfur atoms where the S-Cu(I) distance was measured to be 2.3 Å in EXAFS experiments (21, 60). To correctly orient the metal binding residues for Cu(I)-binding in the apo systems, we employed 2 ns of steered MD on each of the 25 systems to bring the metal binding residues (M21, M36, and M38) into an hypothetical pre-organized state where the sulfur atoms would be 4.15 Å distant from each other in an equilateral triangular alignment using a harmonic restraint of 1000 kcal/mol*Å2. This distance value was obtained from our optimization efforts involving methionine side chains and a Cu(I) ion at the density functional theory (DFT) QM level which were performed with Gaussian’09 (61) using the M06L DFT functional (62) in conjunction with the double-ζ-quality LANL2DZ pseudopotential basis set for Cu(I) (63) and the Pople type basis set 6–31G* for all the other atoms (64). In addition to providing the needed S-S distances and a general positioning in the metal site for the steered MD, these calculations confirmed the experimentally observed Cu(I)-S distance of 2.3 Å. Once we obtained the individual “pre-organized” geometries for the metal site on 25 models, we introduced the Cu(I) ion in the center of mass of the three sulfur atoms of M21, M36, and M38 after we had stripped all the solvent and counter ions from the final recorded snapshot at the end of the 2 ns simulation time which yielded 25 holo models. The metal-bound systems were represented by a bonded model where the metal parameters were obtained with MTK++/MCPB functionality (65) of AmberTools version 1.5 (66). A frequency calculation was run on the optimized structure (M062X/LANL2DZ-6-31G*) of the binding site using Gaussian09 to collect the bond and angle parameters (67). The charges for the Cu(I)-bound ligands were calculated using RESP (M062X/6-31G*) within the MTK++ program (68, 69).

Having equilibrated the apo models and holo models, we proceeded with 200 ns of conventional MD and 400 ns of accelerated MD (aMD) (70) for each of these 50 systems which adds up to a total simulation time of 5 microseconds of MD and 10 microseconds of aMD for both apo and holo models. The MD simulations were run with the ff99SBildn force field (71) of the AMBER11 package (66) where for the aMD simulations, the same force field in the AMBER12 suite was utilized (72). The aMD parameters were obtained from the 200-ns MD runs for each of the 50 systems as described in the AMBER12 manual and an extra boost was applied to the torsions (Table SI.2). Throughout the production simulations the SHAKE algorithm was used to constrain covalent bonds involving hydrogen. The Particle mesh Ewald (PME) method was utilized for long-range electrostatic interactions and an 8-Å non-bonded cutoff was applied to limit the direct space sum in PME (73). The temperature of the systems was maintained at 300 K with Langevin dynamics (collision frequency of 1.0 ps−1). Frames were collected every 2 ps. A selected subset of these snapshots were employed in distance, angle, dihedral, root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), correlation analyses, entropy calculations and clustering of trajectory frames with the ptraj utility of AmberTools version 1.5. The average-linkage algorithm with a maximum eccentricity of 5 Å was used in clustering the frames. NMR chemical shifts were assigned to backbone atoms extracted from snapshots separated by 0.5 ns with SPARTA+ (74). A smaller subset of these snapshots with a frame separation of 20 ns was employed in secondary structure predictions with the Stride program (75). Visual molecular dynamics (VMD) was utilized to visualize the molecular structures (76) while Gnuplot (77) and Grace software were used to plot the data.

Results and Discussion

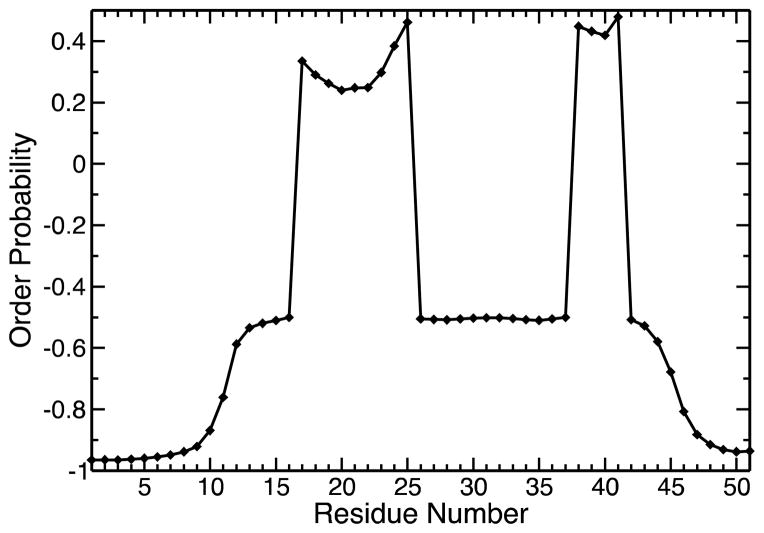

The N-terminus of CusB was found to be mostly disordered in previous circular dichroism and NMR experiments involving its apo and Ag(I)-bound versions (23). Before we started with the MD simulations, we assessed the expected level of disorder in the CusB N-terminus with SPINE-D, an online artificial neural network server which classifies regions of a given protein chain as ordered or disordered based on the protein sequence only (53). The results are shown in Figure 1 and CusB-NT is predicted to have significant disorder while some order was estimated for two regions around the residues 16–25 and 38–41, which roughly corresponded to the metal coordination sites. This result, combined with the experimental findings, prepared us for the fact that a very careful analysis was needed to extricate insights into the intrinsically disordered protein.

Figure 1.

The predicted level of order for each residue by the online server SPINE-D. The scale for order probability is from +1 to −1 where +1 implies a maximum probability for order, namely complete order, and −1 expresses a maximum probability for disorder, in other words, total disorder.

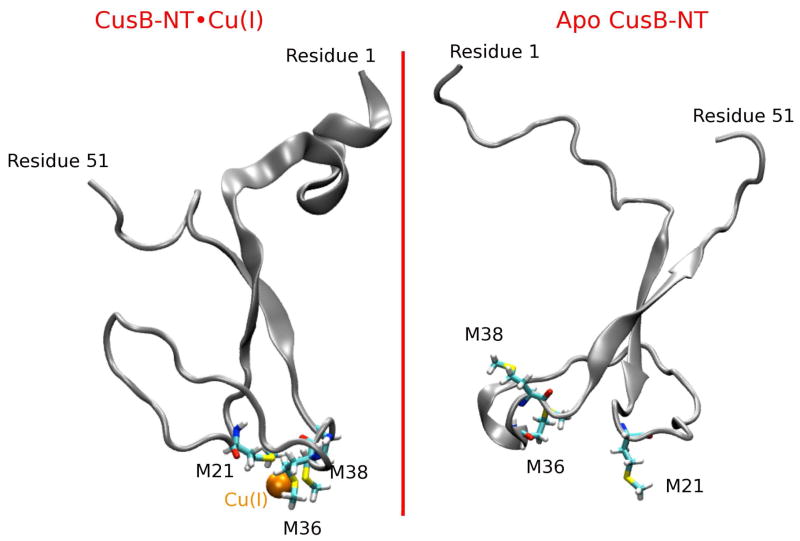

Both in the apo and holo trajectories of CusB N-terminus domain, there are some motifs which were visually observed repeatedly: an anti-parallel beta sheet configuration in the central part, a small beta-sheet structure at the N-terminus of the CusB-NT chain which sometimes aligns with the antiparallel beta sheets in the center to form a triple antiparallel beta sheet conformation, the N- and C-termini tails folding into short helices, and the 1-turn α-helix in the loop connecting the metal binding residues M21 and M36. Figure 2 gives sample structures observed in the simulations containing some of these features. Naturally, the Cu(I) ion bound to the three Met residues M21, M36 and M38 provides some degree of constraint to the chain motion which renders the holo form slightly more ordered around the metal binding region. Hence, the apo protein adopts a larger number of conformations. For both forms, we observed the maximum mobility in the CusB-NT chain ends. The N-terminal end, (residue numbers 1–10), is even more mobile than the C-terminal end and the latter would normally be attached to the rest of the CusB chain whose crystal structure had been already resolved by X-ray crystallography techniques. Both in the holo and the apo forms, the N-terminal of the CusB-NT chain often folds into a small alpha helix in addition to the beta sheet it forms occasionally. As our RMSD analysis suggests though (see Figure 4, SI Fig. 2 and discussion below), substantial structural changes occur during the simulations. We observe numerous structural motifs, ranging from rather extended to more globular where the termini and the M21-M36 loop fold against the antiparallel beta sheet motif in the center. Hence, the beta sheets act like a core region leading to a rather compact shape along with the M21-M36 loop and the transient secondary structure (beta strand or alpha helix) in the C-terminus of the CusB-NT.

Figure 2.

The Cu(I)-bound version of the CusB N-terminal region is shown on the left and its apo version on the right. The central beta motif with the two antiparallel beta strands, the loop connecting the metal binding residues M21 and M36 and the disordered tail regions are indicated in these sample structures. The short alpha helix on the N-terminal end of CusB-NT forms very frequently in both the holo and apo versions.

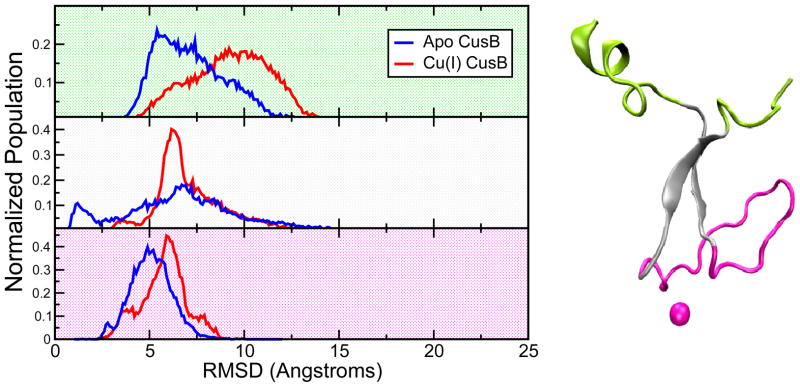

Figure 4.

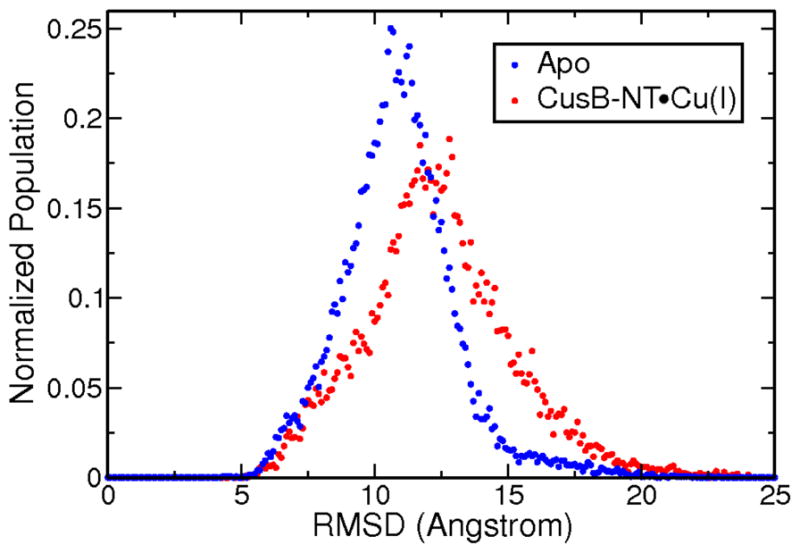

Distribution of RMSD values over 10 microseconds of aMD for apo and Cu(I)-bound versions of the CusB-NT chain. The means and the standard deviations for both versions do not differ significantly implying comparable structural mobilities before and after metal binding.

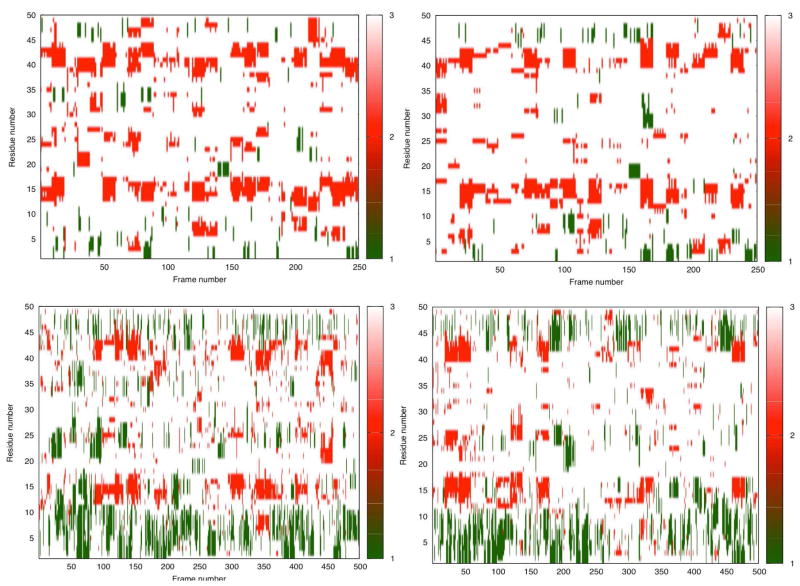

We also made use of secondary structure predictions to quantify the observed structural similarities between the apo and Cu(I)-bound protein models. These were established using the Structural Identification (STRIDE) algorithm which uses atomic coordinates for assignment (75). The frames were isolated from the MD and aMD trajectories and the secondary structure elements assigned to each frame were combined into a matrix, which was displayed with the color-coding as seen in Figure 3. We analyzed the MD and aMD data separately in each case. Since we simulated the holo version for a longer time using aMD, we ended up with more frames contributing to this matrix because the frame separation was kept at 20 ns at all times. It must be noted that the covered phase space with aMD going from one frame to the next, is larger due to the enhanced sampling of aMD. Hence, greater structural changes are to be expected. Actually, our test runs indicate an acceleration of three to forty five-fold in sampling the phase space depending on the starting point (Figure SI.4) as tracked from the backbone RMSD profiles of arbitrary model structures. Thus, the MD trajectories tend to retain the secondary structure elements over consecutive frames. On the other hand, the aMD trajectories gives a more striped appearance due to the increased conformational variability of the snapshots and do not stack up as seen in MD matrices. The bottom panels reveal this effect very clearly: the longer the separation between the snapshots, the less continuous the matrix representation.

Figure 3.

The STRIDE secondary structure predictions for the (top left) apo CusB-NT, MD trajectories; (top right) Cu(I)-bound CusB-NT, MD trajectories; (bottom left) apo CusB-NT, aMD trajectories; (bottom right) Cu(I)-bound CusB-NT, aMD trajectories. Color scale: 1/green-alpha helix, 2/red-beta sheet, 3/white-turn, coil or not assigned.

For both apo and holo simulations, turns and coils shown in white dominate in terms of the observed secondary structures, which implies a large extent of disorder throughout the protein structure. In addition to these, the persistence of the beta sheet motif can be seen in the red spots around residues 13–16 and 40–44. In the aMD trajectories, the alpha helix in the beginning part of the chain (first ten residues) dominates the picture. Helices are known to require time frames around 200 ns to form, which in turn makes them rarer in our MD trajectories (78, 79) in comparison to the aMD trajectories. The small helix forming in the loop region connecting M21 and M36 sometimes appears in the apo aMD simulation, but it’s not a persistent structural element for the holo version. The most significant insight gained through these matrix representations is how much disorder is seen throughout the protein chain. Nonetheless, this analysis gives structural and timescale insights into the formation and unraveling of secondary structural elements in a disordered protein. (80)

RMSD data served as another tool to assess the extent of structural variability of the apo and holo versions of the CusB N-terminal. The RMSD ranges and distributions observed in the MD trajectories for individual apo and holo models do not differ drastically as seen in Figure 4 and SI.2. The mean RMSD for the apo aMD trajectories is 10.86 ± 2.11 Å while for the holo aMD trajectories it is 12.32 ± 2.76 Å. The RMSDs of the apo models span a range of 5–18 Å where changes within one trajectory are minor: usually about 2 Å, although it reaches 6 Å for some models (Figure SI.2).

Surprisingly, the RMSD spread for the holo models is 6–22 Å while the RMSD within one trajectory remains mostly at much lower values of 2–3 Å. Here we experience the benefits of having started our MD runs from twenty-five distinct starting points to end up with good overall sampling. The RMSD values for each starting structure with respect to an arbitrary starting structure were computed to determine how dissimilar the starting models were and the resulting plot is given in the SI (Figure SI.5). The aMD data broadens the observed RMSD ranges slightly: 5–23 Å for apo and 4–24 Å for the holo models. More importantly, the RMSD ranges spanned by single trajectories exceed 10 Å in certain cases which indicates better sampling, as expected, and would push the different conformations from different portions of the potential energy surface to other regions. In this way “energetic traps” were avoided by switching to different starting points.

The Cu(I)-bound structures experience greater structural changes both in the MD and aMD trajectories compared to their apo counterparts which is counterintuitive with what one would anticipate because of the reasonable hypothesis that the metal ion would restrain the chain motion. This is observed both in the individual RMSD profiles and in the distribution of the RMSD values for the apo and holo trajectories. In Figure 4, the distribution of the RMSD values associated with the holo trajectories is broader and its mode is greater than the one for the apo distribution. Although the analyzed trajectories are from the production phase, it appears that the polypeptide chain is still adapting to this extra constraint by fluctuating to a greater extent and searching for stable conformations. More detailed RMSD profiles are shown in Figure SI.2. This is in contrast to recent work on CzrA, where metal binding (Zn(II)) lead to a reduction in the number of states sampled by CzrA relative to its apo state. (81)

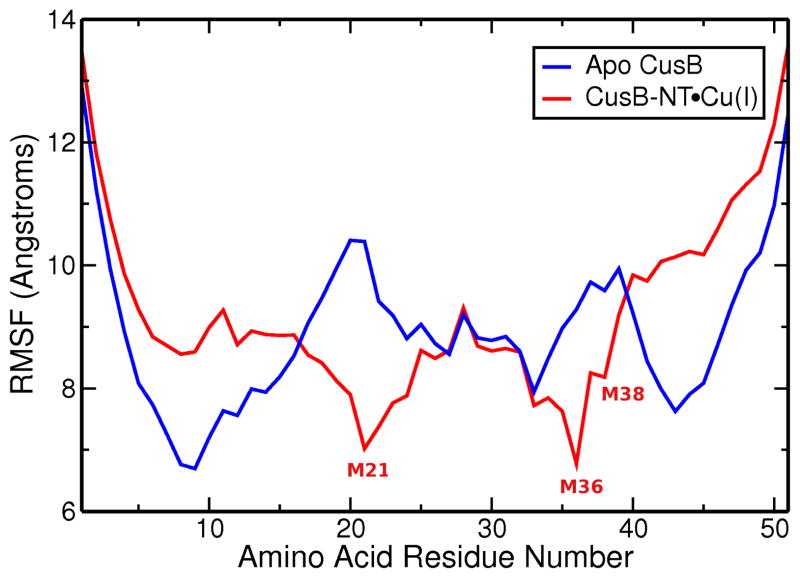

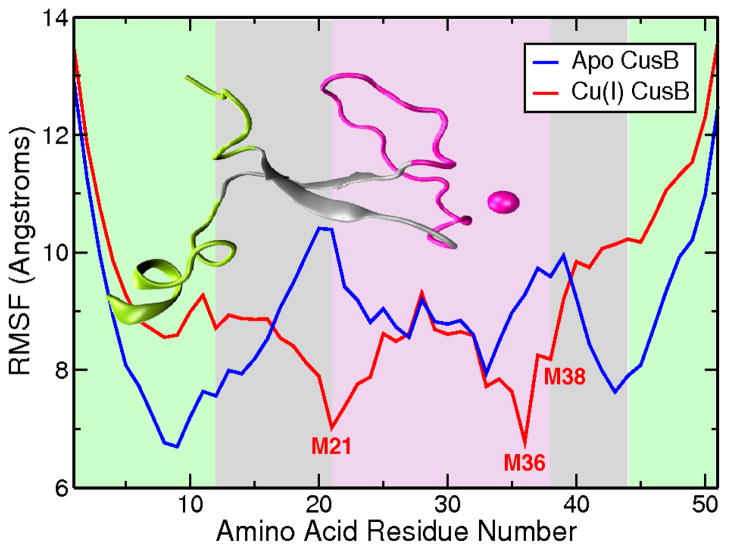

The RMSF profile is a measure of the mobility of the alpha carbons of the protein chain. In this case, the analysis shows that the end residues are more mobile compared to the rest of the molecule for both apo and holo conformations. The individual plots obtained from the individual MD trajectories contain various minima and local maxima in the interior parts of the chain (Figure SI.3). The RMSF profiles from the aMD trajectories provided useful insight where some trends are observable: for the apo models the most stable, i.e. showing the lowest atomic fluctuations, residues are T9, R12, I14, F27, S33, and K43 as seen in Figure 5. The reduced mobility around residue T9 is mostly associated with the formation of the alpha helix in the N-terminus tail of CusB-NT, which ceases to some extent upon addition of metal as indicated in the lower panels of Figure 3. I14 and K43 fall into the beta sheets making up the central beta sheet motif, which emphasizes the tendency for this secondary structural element to form and stay stable over long time frames. R12 is adjacent to the first beta strand and is stabilized by the central beta motif. F27 and S33, on the other hand, are involved in extensive hydrogen bonding with other residues in the M21-M36 loop (Figure 10- see discussion below). This intermolecular interaction network reduces the mobility of these two residues. The loop region between M21 and M36 becomes almost as mobile as the tails of the chain towards the middle for some of the trajectories (Figure SI.3). Incorporation of the metal introduces a constraint to free motion and diminishes the atomic fluctuations of the metal ligating residues (indicated in Figure 5). The minima of the averaged atomic fluctuations for the holo version of the CusB N-terminal region are found at M21 and M36. Interestingly, the Cu(I)-binding residues M21, M36, and M38 in the holo models do not necessarily show minimal fluctuations in some of the individual trajectories. We ensured that this does not trace back to the disruption of the metal site; the S-Cu(I) distances have been analyzed throughout and were confirmed to conserve the bonding distances at all times. Visual inspection aids in confirming these seemingly contradictory observations: The loop connecting the M21 and M36 residues moves to both sides of the central beta sheet motif similar to a flap which enhances the mobility of the Met’s bound to Cu.

Figure 5.

Atomic fluctuations for the apo (blue) and Cu(I)-bound (red) versions of the N-terminal region of CusB. Data were collected over a total of 10 microseconds of aMD simulations from 25 different starting points. Cu(I) binding seems to impact only the metal binding residues, M21, M36 and M38. The cumulative RMSF graph obtained using the MD data can be found in SI (Figure SI.8). General trends are conserved in the MD results versus aMD.

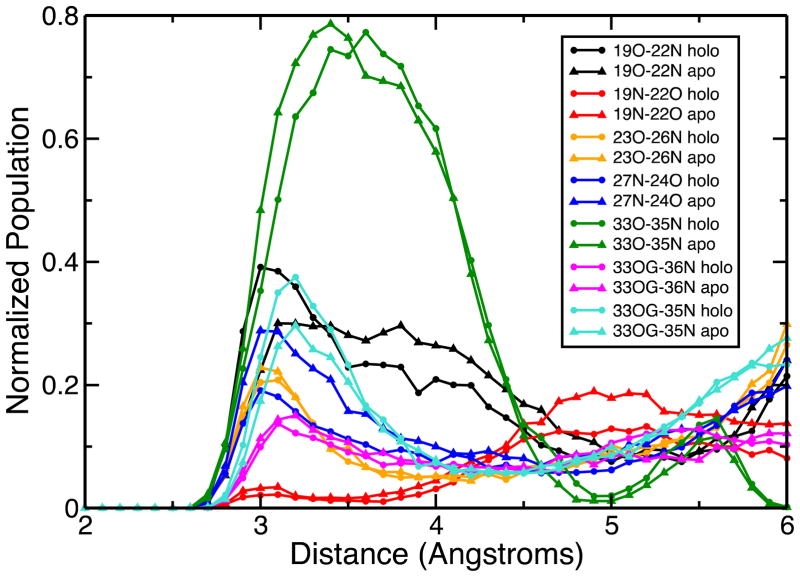

Figure 10.

Distance analysis plot for residues in and adjacent to the big loop connecting residues M21 and M36. The triangles indicate data obtained from the apo trajectories while the dots are for the holo trajectories. The numbers in the inset are the residue numbers. “O” represents the backbone oxygen, “N” the amide nitrogen and “OG”, the side chain oxygen of S33.

Comparing the atomic fluctuation profiles of single models obtained from the aMD trajectories reveals that the minima are less spread in the holo chain (Figure SI.3). The fact that the immobilization effect remains only local around the metal binding residues becomes even more obvious in the cumulative RMSF profiles in Figure 5. Looking at the individual profiles of the apo models, on the other hand, the motions seem to be dispersed along the chains more evenly (Figure SI.3). However, this artifact disappears in the cumulative graph.

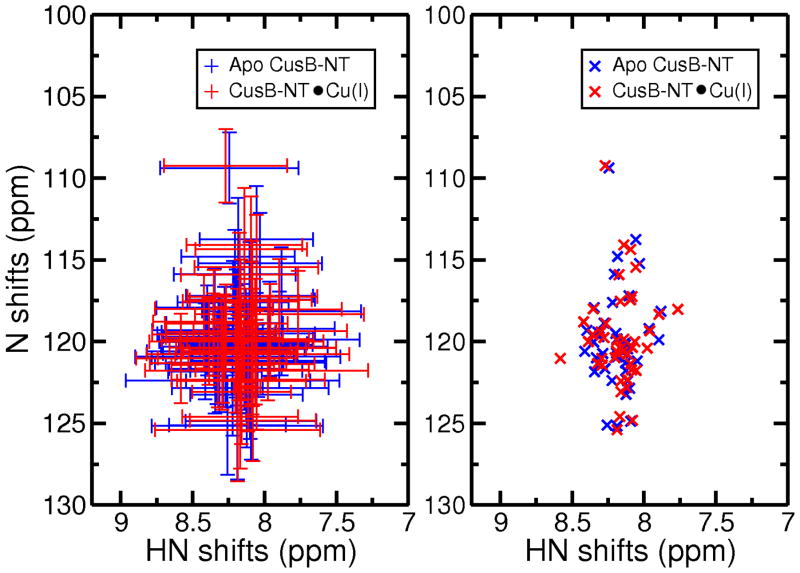

We next calculated NMR chemical shifts for the apo and holo forms of CusB-NT using SPARTA+ (74). These shifts were calculated for a total of 20,000 snapshots of the apo and holo models and averaged structures. The program could only calculate 43 backbone N’s and their associated H’s because the first amino acid residue is exempt from predictions and there are seven Pro residues without an amide hydrogen leaving 43 residues in total. The average shifts for the backbone nitrogens (N) and their hydrogens (HN) were plotted with and without their standard deviations (Figure 6). The conclusion, which can be drawn from these calculations, is that no striking structural differences other than the local organization of the metal binding site occur between the apo and the Cu(I)-bound versions of the CusB N-terminal, which is consistent with the experimental observations involving Ag(I). (23) Additionally, this resembles the metallochaperone CusF where the apo and the metal-bound structures were similar to each other. (12, 82–84)

Figure 6.

Average NMR Shifts for backbone N’s and their H’s for the apo (blue) and Cu(I)-bound (red) predicted by SPARTA+ (right) and their standard deviations (left).

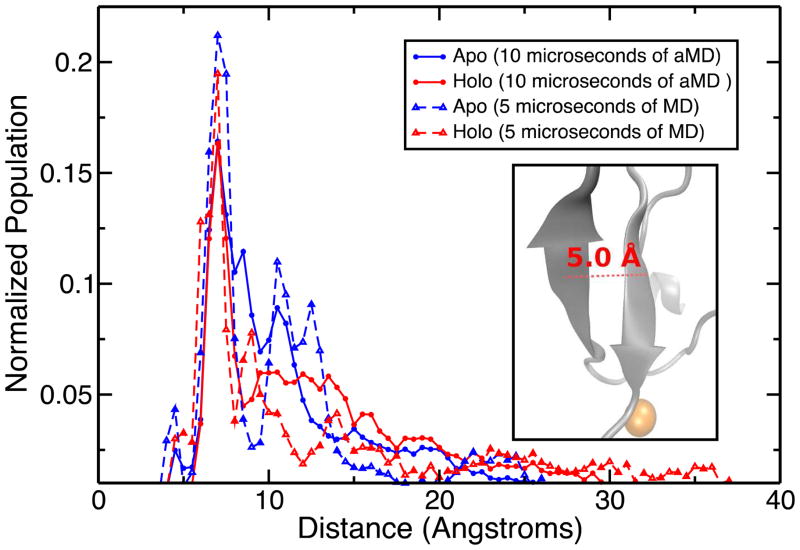

In addition to the above, we investigated numerous structural properties in order to identify the structural changes induced by the metal binding. To determine these properties, we focused on the prominent structural motifs. The first was the beta sheet motif in the center of the chain. The distance between the two antiparallel beta strands measured from the center of mass of the residues 13–16 (strand 1) to the center of mass of the residues 41–44 (strand 2) emerged as a good coordinate to estimate the extent to which these two beta sheets maintained their antiparallel alignment. This distance is measured to be around 5–6 Å when the two beta sheets are found to be in the antiparallel configuration. The inset of the Figure 7 further illustrates this distance. The histogram showing the distribution of this distance over the apo and holo trajectories shows that the majority of the observed snapshots locates the two beta strands 5–6 Å apart from each other which implies that this central motif is one of the key structural elements in this disordered protein chain (Figure 2). The range for this specific distance spans values from 3 to 66 Å, suggesting that most, if not all of the available phase space is visited.

Figure 7.

Distribution of the distances between the two beta sheets forming the central beta motif. The distribution from the apo MD/aMD trajectories are shown in blue and the data from the holo MD/aMD trajectories are displayed in red. The inset visualizes this property. In this particular conformational alignment, the distance measures exactly 5.0 Å. The vast range of distances suggests that we have extensively sampled the available phase space.

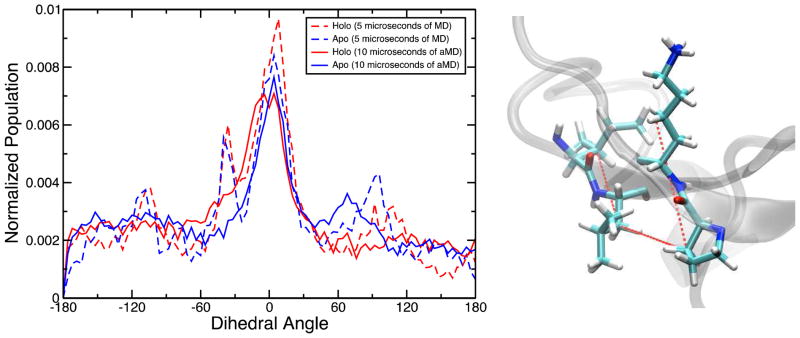

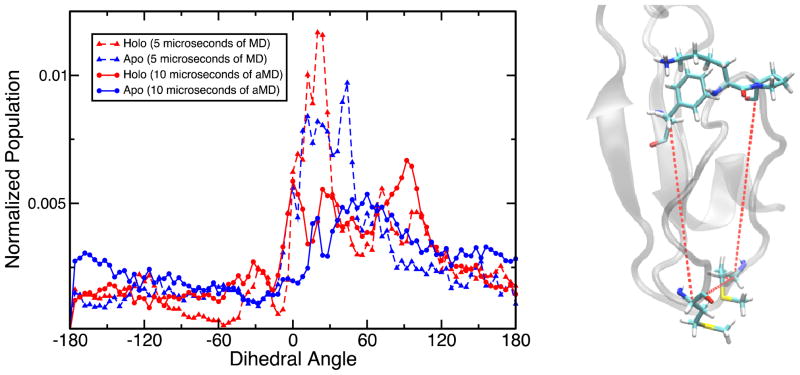

Secondly, to check the relative positioning of the two beta strands belonging to the central beta motif the dihedral angle formed by the centers of mass of L15, I14, K43, and P42 residues was probed (Figure 8, right). Dihedral angles of 0 degrees would imply an antiparallel conformation. As seen in the histogram in Figure 8, the global maximum occurs at around 0 degrees for both the apo and the holo trajectories of CusB-NT suggesting that the antiparallel beta conformation is the most favored although it comprises only ca. 10% of the whole spectrum. Other peaks occur around −120, −30, 60, and 90 degrees indicate other common alignments in the trajectories. The similarity in behavior of the apo and holo models underlines the fact that this beta motif is one of the key structural features of the CusB N-terminal region, as suggested by the data of Figure 7.

Figure 8.

The dihedral angle formed by L15, I14, K43 and P42 as a measure of the relative beta sheet positions in the central motif (right). The distribution of this property is shown in the plot over the apo (blue) and holo (red) trajectories.

Further analysis aimed to explore the conformational preferences of the loop connecting M21 and M36 relative to the central beta motif, whose importance we have highlighted. The dihedral involving the center of mass of F16 (in the central beta sheet), M21, M36 and the common center of mass of the residues D28, K29 and P30, which falls on the midpoint of the big loop connecting M21 and M36, was examined for this purpose (Figure 9, inset). Not surprisingly, the apo and Cu(I)-bound models do not differ significantly. It appears that this loop tends to locate itself somewhere on the range of 0–120 degrees from the central beta motif while for the holo models, angles of 0–30, 70–80, and 90–100 degrees dominate. For the apo models, dihedrals of 0–60 degrees are more common (Figure 9). As more sampling is included in the analysis with the aMD trajectories, the peaks covering the range of 0–60 degrees flatten out for both the apo and the holo models giving rise to a more dispersed distribution. The distribution of the data obtained from the holo aMD trajectories shows two maxima at around 0–30 and 90 degrees. The one associated with the apo aMD data peaks at around 30–70 degrees.

Figure 9.

The dihedral involving the center of mass of F16 (in the central beta conformation), M21, M36 and the common center of mass of the residues D28, K29 and P30 is shown in the inset. The distribution of this property is shown in the plot over the apo (blue) and holo (red) trajectories.

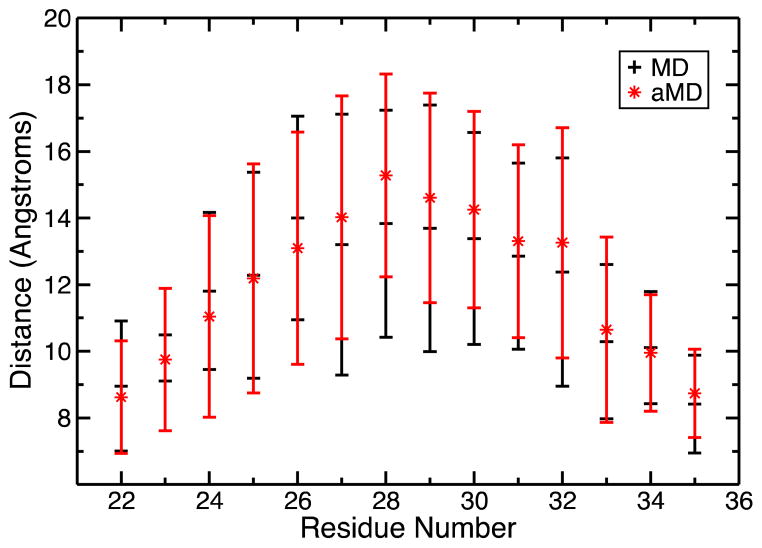

To further understand the spatial alignment of the loop, a distance analysis was conducted on the residues, which constitute the loop (residues 22–35) and the ones close to the loop (residues 17, 19, 37, and 39), which may interact with the loop residues. Figure 10 shows these distance trends: hydrogen bonding between the backbone oxygen of S33 and the amide hydrogen of F35 occurs in almost 80% of all the snapshots taken both from the apo and holo trajectories. This is by far the most prevalent interaction inferred from this analysis. In 50% of the snapshots this hydrogen bond is a strong one since the carbonyl oxygen-amide nitrogen distance is less than 3 Å. S33 and F35 are located at the hinge of the loop when it folds against the beta motif, and favor this type of folded alignment. The side chain oxygen of the S33 and the amide hydrogen of F35 also interact in ~25% of all the frames in the apo and Cu(I)-bound simulations. This interaction alternates with the previous S33O-F35NH interaction from time to time, emphasizing the importance of F35 and S33 in determining the spatial arrangement of the loop. Alternatively, the side chain oxygen of S33 interacts with the amide hydrogen of M36 in almost 10% of the snapshots taken from both the apo and holo trajectories. This adds to the structural importance of residue M36: binding the Cu(I) ion and aiding in structural organization of the domain by facilitating the folding of the big loop with hydrogen bonds at the hinge point. In addition to these interactions, the backbone carbonyl oxygen of D19 and the amide H of Y22 form a backbone hydrogen bond on the other end of the loop and this acts as a hinge as well which is observed in ~20% of the apo and ~40% of the holo conformations. Very rarely, the amide H of D19 and the backbone O of Y22 form hydrogen bonds. Another interesting point revealed in the distance analysis is the formation of the 1-turn helix within the M21-M36 loop whose formation is made possible through the backbone hydrogen bonding involving the residues P23-R26 and N24-F27. This is observed in almost 20–30% of the apo and holo models.

An additional structural property was examined to gain insight to the general shape of the M21-M36 loop. The distance between the Cu(I) ion and the center of mass of each residue constituting the loop connecting M21 to M36 was calculated for every snapshot taken from the holo trajectories (Figure 11). This analysis reveals that the loop is mostly oval shaped. Standard deviations increase for residues closer to the middle of the loop implying that they are more mobile as they move further away from the hinge points.

Figure 11.

Distance between the Cu(I) ion and the centers of mass of each residue constituting the loop connecting M21 to M36 along with error bars.

Finally, to examine the reversibility of the structural effects caused by metal binding, we randomly picked one of the 25 models and removed the Cu(I) ion from snapshots at 100 ns (“snapshot 1”) and 200 ns (“snapshot 2”) into the conventional MD simulation. We solvated, minimized, and equilibrated these two structures using the protocol described in the methods section and ran 200 ns of conventional MD on them. We tracked the backbone motions of the new trajectories both visually and with root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) and root mean square deviation (RMSD) analyses. These were compared to the corresponding analyses of the original apo trajectory of the same model. The comparisons are shown in Figure SI.9 and Figure SI.10. Accordingly, both the RMSD and RMSF profiles of snapshot 1 track the backbone motions of the original apo trajectory very closely, which suggests they may be covering similar regions of phase space. However, for snapshot 2 the recovery of apo behavior was not as clear. Although the original apo behavior of this particular model is not obtained in the snapshot 2 trajectory, the main secondary structural elements like the central beta motif and the loop between M21 and M36 emerge in the middle of the trajectory, which is a point visited by other apo models, as the STRIDE analysis qualitatively demonstrates

Decomposing the Disorder

Our original hypothesis envisioned that we would be able to extract probable structures for the Cu(I)-bound version of the CusB N-terminal region, which would further guide experimental analysis of this domain. Through visual inspection and the RMSF analyses, we observed the chain ends to be, not surprisingly, more mobile than the rest of the chain. This led to the idea of splitting the chain into three “subdomains” and analyzing these individually: The tails, the central beta motif, and the Cu(I)-site along with the big loop. These are shown in the insets of Figure 12 and Figure 13. Considering the atomic fluctuations of the alpha carbon atoms presents a useful quantitative way to justify how we determined the subdomains. As seen in Figure 12, the fluctuations behave consistently in the designated subdomains. Both tails show elevated backbone motion in the Cu(I)-bound version compared to the apo, which is designated as the first subdomain and displayed with a green background. In the central beta motif there is a changing trend in the RMSF: the beta region of the holo models become less mobile towards the metal binding site while this is inverted for the apo models. In other words, the chain fluctuations decrease in the holo models as one approaches the Cu(I) site while the opposite behavior is observed in the apo models. Thus, the region can also be considered as a distinct subdomain and is indicated with a grey background in Figure 12. The M21-M36 loop region constitutes the third subdomain as it displays a local stabilization upon metal binding, and a higher mobility in the apo models (pink background).

Figure 12.

The RMSF profiles of apo and holo CusB N-terminal revisited with background color-coding. Green is for the tails, grey for the central beta motif and pink the M21-M36 loop. The inset figure shows these three subdomains.

Figure 13.

(right) The N-terminal domain of CusB was split into three subdomains to decompose the structural disorder: 1. The tails (green), 2. The central beta motif (grey), 3. The Cu(I)-site and the M21-M36 loop (magenta). (left)The RMSD distributions associated with these subdomains extracted from 10 microseconds of aMD runs on the Cu(I)-bound protein: green background-subdomain 1, gray background- subdomain 2, and pink background- subdomain 3.

In this partitioning, the most stable subdomain was the Cu(I)-site and the M21-M36 loop followed by the central beta sheet motif and then the tails as seen in the RMSD distribution in Figure 13. The RMSD distribution profile shows that the tails have the highest extent of structural changes yielding the widest RMSD distribution with the greatest mode value of almost 10 Å, further confirming that the most significant chain motion happens there. Interestingly, the biggest change in the RMSD distributions upon metal binding is detected in the beta motif region which points to the largest acquired ordering in contrast to what might have been expected to happen in the third subdomain containing the metal site and the loop. The beta motif is likely to assist in generating a pre-organized state suitable for metal binding and this hypothesis emphasizes its structural significance. The average RMSF profiles in Figure 12 also support this finding where the alpha carbons of the residues constituting the Cu(I)-site and the big loop display the lowest atomic fluctuations while the highest atomic fluctuations stem from the tails of the protein chain. Additionally, clustering the split trajectories yielded a much lower number of clusters in general, while the lowest number of clusters were produced by the most stable subdomain constituting of the Cu(I)-site and the M21-M36 loop. More specifically, a subset of 6,000 frames from each subdomain was clustered using the ptraj utility of AmberTools version 1.5 using the average linkage algorithm, which resulted in 303, 22, and 4 clusters for subdomains 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Hence, we could observe that the tails are mostly responsible for the disordered state of the N-terminal region of CusB. This led us to isolate the tails (subdomain 1) from the CusB-NT and cluster the remainder, namely the subdomains 2 and 3. This protocol provided us with 261 clusters, which is a large decrease from the 1646 clusters when the entire CusB-NT chain was analyzed in an analogous manner. Thus, the observed disorder can be largely attributed to subdomain 1, the N- and C-termini, of the CusB-NT domain. Based on this observation we propose that even the smaller construct of subdomains 2 and 3 might form a functionally competent metal binding domain.

Conclusions

In this study we explored the conformational dynamics of the apo and Cu(I)-bound CusB N-terminal region to assess the impact of metal binding on this mostly disordered protein domain, which lacked an experimentally resolved structure. To obtain viable starting points, we utilized online protein folding servers Quark (47), I-Tasser (48, 49), and Sparks-X (50) which gave promising results in CASP competitions. 25 starting models were obtained and used in extensive MD simulations to study the structure and dynamics of the CusB N-terminal region. Moreover, we applied the accelerated MD enhanced sampling method of Pierce et al. (70) for another 10 microseconds of sampling in addition to 5 microseconds of classical MD simulations. The Cu(I) ion was inserted into the apo models after generating pre-organized metal binding sites according to the available experimental information regarding the binding site. A bonded force field was created which attached the three coordinating Met residues (M21, M36 and M38) to the Cu(I) ion in a trigonal planar (triangular) alignment over the course of these simulations. The holo models generated in this way were simulated for the same amount of simulation time, which provided us with sufficient conformational dynamics and structural information to compare the apo and metal-bound versions of the CusB N-terminal domain.

Our analysis of the secondary structure assignments, RMSD, atomic fluctuations of alpha carbons, NMR chemical shift assignments, and various structural coordinates focusing on the more prominent motifs like the central beta sheet and the M21-M36 loop showed that significant disorder was present in both the apo and Cu(I)-bound forms of the protein. Metal binding only led to a local ordering around the metal site causing a modest impact on the disorder of the whole domain. To reduce the complexity of this general disorder, the protein was broken up into three subdomains utilizing logically selected structural elements. The first subdomain consisted of both tails (residues 1–12, 46–51); the second contained the two beta strands in the center of the structure (residues 13–20, 39–45) and the third subdomain consisted of the M21-M36 loop in the apo chain along with the Cu(I) ion in the holo version. The RMSD analysis carried out on these regions showed that the first subdomain with the N and C-terminal tails showed the most disorder and was not affected by metal binding. Surprisingly, the biggest structural impact upon Cu(I)-binding occurs in the beta motif region, namely the second subdomain, in contrast to our anticipation where the binding site and the loop (the third subdomain) would be influenced the most. This finding suggests that the beta motif region is of utmost structural importance in the function of CusB as a metal chelator in the CusCFBA metal extrusion mechanism. Indeed, our simulations suggest that residues 13–45 would also function in a similar manner to the entire chain since the two tail regions do not form any significant structure during the simulations, and this prediction can be tested experimentally.

The role of CusB-NT for metal delivery offers a conundrum. The concept of preorganization (85) suggests that in order to have tight and selective metal ion binding the receptor should adopt a structure similar to that of the complexed structure. Experimentally, CusB-NT appears disordered both in the apo and metal loaded forms as determined by NMR. (23) Computationally there appears to be a modest level of structural preorganization in CusB-NT in residues 13–45, which was also seen for CusF (12, 82–84), but it is still remarkable that this protein, which preforms an important and essential function, has characteristics that suggest that it might not sequester Cu(I) from the environment at levels typically seen in Cu(I) binding proteins. (86) This disorder appears to be carried over into the intact complex as observed in the X-ray structures of the CusBA system. (18, 87) Perhaps association with CusF induces further order or once metal is bound in the intact complex interactions between the metal binding domain and the intact transporter induces further stabilization.

To summarize, our simulations concluded that CusB-NT largely remains disordered with only the central region of this protein (residues 13–45) forming secondary structure elements. Interestingly, this situation is not significantly affected by metal binding in opposition to our initial biases. This study has set the stage to simulate this domain with its functional companion CusF, the metallochaperone of the CusCFBA Ag(I)/Cu(I) pump. Another goal is to attach the CusB N-terminal to the remainder of CusB to see how it interacts with the intact copper transport system. The presence of these companion proteins might result in an increased order of this region and further insights into the metal ion transport mechanism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ross Walker, Dr. Romelia Salomon and Ms. Antonia Mey for useful scientific discussions. This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health via grants GM044974 and GM066859. We acknowledge the University of Florida High Performance Computing Center for providing technical support.

Abbreviations

- E. coli

Escherichia coli

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RND

resistance-nodulation-division

- MFP

membrane fusion protein

- CASP

Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction

- AMBER

Assisted Model Building with Energy Refinement

- TIP3P

transferable intermolecular potential 3P

- MD

molecular dynamics

- aMD

accelerated molecular dynamics

- EXAFS

Extended X-Ray Absorption Fine Structure

- DFT

density functional theory

- QM

quantum mechanics

- RESP

restrained electrostatic potential

- MCPB

metal center parameter builder

- RMSD

root mean square deviation

- RMSF

root mean square fluctuation

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- SPARTA

Shifts Prediction from Analogy in Residue Type and Torsion Angle

- VMD

visual molecular dynamics

- CusB-NT

CusB N-terminus

Footnotes

Supporting information including detailed RMSD and RMSF profiles, metal coordination site images, coordinates and input parameters are available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Zhang Y, Gladyshev VN. Comparative Genomics of Trace Elements: Emerging Dynamic View of Trace Element Utilization and Function. Chem Rev. 2009;109:4828–4861. doi: 10.1021/cr800557s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macomber L, Rensing C, Imlay JA. Intracellular copper does not catalyze the formation of oxidative DNA damage in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:1616–1626. doi: 10.1128/JB.01357-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poole K, Srikumar R. Multidrug efflux in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: components, mechanisms and clinical significance. Curr Top Med Chem. 2001;1:59–71. doi: 10.2174/1568026013395605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piddock LJV. Multidrug-resistance efflux pumps - not just for resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:629–636. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang S, Lopez CR, Zechiedrich EL. Quorum sensing and multidrug transporters in Escherichia coli. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2386–2391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502890102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tseng TT, Gratwick KS, Kollman J, Park D, Nies DH, Goffeau A, Saier MH. The RND permease superfamily: an ancient, ubiquitous and diverse family that includes human disease and development proteins. Journal of molecular microbiology and biotechnology. 1999;1:107–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dinh T, Paulsen IT, Saier MH. A Family of Extracytoplasmic Proteins That Allow Transport of Large Molecules across the Outer Membranes of Gram-Negative Bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3825–3831. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.13.3825-3831.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zgurskaya HI, Nikaido H. Multidrug resistance mechanisms: drug efflux across two membranes. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:219–225. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franke S, Grass G, Nies DH. The product of the ybdE gene of the Escherichia coli chromosome is involved in detoxification of silver ions. Microbiol-Uk. 2001;147:965–972. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-4-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franke S, Grass G, Rensing C, Nies DH. Molecular analysis of the copper-transporting efflux system CusCFBA of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:3804–3812. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.13.3804-3812.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munson GP, Lam DL, Outten FW, O’Halloran TV. Identification of a copper-responsive two-component system on the chromosome of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5864–5871. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.20.5864-5871.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loftin IR, Franke S, Roberts SA, Weichsel A, Heroux A, Montfort WR, Rensing C, McEvoy MM. A novel copper-binding fold for the periplasmic copper resistance protein CusF. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10533–10540. doi: 10.1021/bi050827b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saier MH, Tam R, Reizer A, Reizer J. 2 Novel Families of Bacterial-Membrane Proteins Concerned with Nodulation, Cell-Division and Transport. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:841–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Su CC, Yang F, Long F, Reyon D, Routh MD, Kuo DW, Mokhtari AK, Van Ornam JD, Rabe KL, Hoy JA, Lee YJ, Rajashankar KR, Yu EW. Crystal Structure of the Membrane Fusion Protein CusB from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 2009;393:342–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tikhonova EB, Zgurskaya HI. AcrA, AcrB, and TolC of Escherichia coli form a stable intermembrane multidrug efflux complex. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32116–32124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402230200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zgurskaya HI, Nikaido H. Bypassing the periplasm: Reconstitution of the AcrAB multidrug efflux pump of Escherichia coli. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7190–7195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zgurskaya HI, Nikaido H. Cross-linked complex between oligomeric periplasmic lipoprotein AcrA and the inner-membrane-associated multidrug efflux pump AcrB from Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4264–4267. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.15.4264-4267.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su CC, Long F, Zimmermann MT, Rajashankar KR, Jernigan RL, Yu EW. Crystal structure of the CusBA heavy-metal efflux complex of Escherichia coli. Nature. 2011;470:558–U153. doi: 10.1038/nature09743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bagai I, Liu W, Rensing C, Blackburn NJ, McEvoy MM. Substrate-linked conformational change in the periplasmic component of a Cu(I)/Ag(I) efflux system. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35695–35702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703937200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kittleson JT, Loftin IR, Hausrath AC, Engelhardt KP, Rensing C, McEvoy MM. Periplasmic metal-resistance protein CusF exhibits high affinity and specificity for both Cu-I and Ag-I. Biochemistry. 2006;45:11096–11102. doi: 10.1021/bi0612622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bagai I, Rensing C, Blackburn NJ, McEvoy MM. Direct Metal Transfer between Periplasmic Proteins Identifies a Bacterial Copper Chaperone. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11408–11414. doi: 10.1021/bi801638m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mealman TD, Bagai I, Singh P, Goodlett DR, Rensing C, Zhou H, Wysocki VH, McEvoy MM. Interactions between CusF and CusB Identified by NMR Spectroscopy and Chemical Cross-Linking Coupled to Mass Spectrometry. Biochemistry. 2011;50:2559–2566. doi: 10.1021/bi102012j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mealman TD, Zhou MW, Affandi T, Chacon KN, Aranguren ME, Blackburn NJ, Wysocki VH, McEvoy MM. N-Terminal Region of CusB Is Sufficient for Metal Binding and Metal Transfer with the Metallochaperone CusF. Biochemistry. 2012;51:6767–6775. doi: 10.1021/bi300596a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akama H, Matsuura T, Kashiwagi S, Yoneyama H, Narita SI, Tsukihara T, Nakagawa A, Nakae T. Crystal structure of the membrane fusion protein, MexA, of the multidrug transporter in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25939–25942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400164200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins MK, Bokma E, Koronakis E, Hughes C, Koronakis V. Structure of the periplasmic component of a bacterial drug efflux pump. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9994–9999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400375101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yum SW, Xu YB, Piao SF, Sim SH, Kim HM, Jo WS, Kim KJ, Kweon HS, Jeong MH, Jeon HS, Lee K, Ha NC. Crystal Structure of the Periplasmic Component of a Tripartite Macrolide-Specific Efflux Pump. J Mol Biol. 2009;387:1286–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dill KA, MacCallum JL. The Protein-Folding Problem, 50 Years On. Science. 2012;338:1042–1046. doi: 10.1126/science.1219021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beauchamp KA, Ensign DL, Das R, Pande VS. Quantitative comparison of villin headpiece subdomain simulations and triplet-triplet energy transfer experiments. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:12734–12739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010880108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bowman GR, Beauchamp KA, Boxer G, Pande VS. Progress and challenges in the automated construction of Markov state models for full protein systems. J Chem Phys. 2009;131:124101. doi: 10.1063/1.3216567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowman GR, Pande VS. Protein folded states are kinetic hubs. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:10890–10895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003962107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowman GR, Voelz VA, Pande VS. Taming the complexity of protein folding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duan Y, Kollman PA. Pathways to a protein folding intermediate observed in a 1-microsecond simulation in aqueous solution. Science. 1998;282:740–744. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freddolino PL, Harrison CB, Liu YX, Schulten K. Challenges in protein-folding simulations. Nat Phys. 2010;6:751–758. doi: 10.1038/nphys1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jayachandran G, Vishal V, Pande VS. Using massively parallel simulation and Markovian models to study protein folding: Examining the dynamics of the villin headpiece. J Chem Phys. 2006;124 doi: 10.1063/1.2186317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lei HX, Wu C, Liu HG, Duan Y. Folding free-energy landscape of villin headpiece subdomain from molecular dynamics simulations. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4925–4930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608432104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pande VS, Baker I, Chapman J, Elmer SP, Khaliq S, Larson SM, Rhee YM, Shirts MR, Snow CD, Sorin EJ, Zagrovic B. Atomistic protein folding simulations on the submillisecond time scale using worldwide distributed computing. Biopolymers. 2003;68:91–109. doi: 10.1002/bip.10219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piana S, Lindorff-Larsen K, Shaw DE. Protein folding kinetics and thermodynamics from atomistic simulation. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:17845–17850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201811109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Voelz VA, Jager M, Yao SH, Chen YJ, Zhu L, Waldauer SA, Bowman GR, Friedrichs M, Bakajin O, Lapidus LJ, Weiss S, Pande VS. Slow Unfolded-State Structuring in Acyl-CoA Binding Protein Folding Revealed by Simulation and Experiment. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:12565–12577. doi: 10.1021/ja302528z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Juraszek J, Bolhuis PG. Sampling the multiple folding mechanisms of Trp-cage in explicit solvent. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15859–15864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606692103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lei HX, Wang ZX, Wu C, Duan Y. Dual folding pathways of an alpha/beta protein from all-atom ab initio folding simulations. J Chem Phys. 2009;131 doi: 10.1063/1.3238567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ozkan SB, Wu GA, Chodera JD, Dill KA. Protein folding by zipping and assembly. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11987–11992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703700104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paschek D, Nymeyer H, Garcia AE. Replica exchange simulation of reversible folding/unfolding of the Trp-cage miniprotein in explicit solvent: On the structure and possible role of internal water. J Struct Biol. 2007;157:524–533. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qiu LL, Pabit SA, Roitberg AE, Hagen SJ. Smaller and faster: The 20-residue Trp-cage protein folds in 4 mu s. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:12952–12953. doi: 10.1021/ja0279141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou RH. Trp-cage: Folding free energy landscape in explicit water. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13280–13285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2233312100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baumketner A, Shea JE. The structure of the Alzheimer amyloid beta 10–35 peptide probed through replica-exchange molecular dynamics simulations in explicit solvent. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:275–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Babu MM, Kriwacki RW, Pappu RV. Versatility from Protein Disorder. Science. 2012;337:1460–1461. doi: 10.1126/science.1228775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu D, Zhang Y. Ab initio protein structure assembly using continuous structure fragments and optimized knowledge-based force field. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics. 2012;80:1715–1735. doi: 10.1002/prot.24065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roy A, Kucukural A, Zhang Y. I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:725–738. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Y. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. Bmc Bioinformatics. 2008;9 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang YD, Faraggi E, Zhao HY, Zhou YQ. Improving protein fold recognition and template-based modeling by employing probabilistic-based matching between predicted one-dimensional structural properties of query and corresponding native properties of templates. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2076–2082. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kinch L, Shi SY, Cong Q, Cheng H, Liao YX, Grishin NV. CASP9 assessment of free modeling target predictions. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics. 2011;79:59–73. doi: 10.1002/prot.23181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu D, Zhang J, Roy A, Zhang Y. Automated protein structure modeling in CASP9 by I-TASSER pipeline combined with QUARK-based ab initio folding and FG-MD-based structure refinement. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics. 2011;79:147–160. doi: 10.1002/prot.23111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang JY, Roy A, Zhang Y. BioLiP: a semi-manually curated database for biologically relevant ligand-protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D1096–D1103. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Y. I-TASSER: Fully automated protein structure prediction in CASP8. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics. 2009;77:100–113. doi: 10.1002/prot.22588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of Simple Potential Functions for Simulating Liquid Water. J Chem Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gordon JC, Myers JB, Folta T, Shoja V, Heath LS, Onufriev A. H++: a server for estimating pK(a)s and adding missing hydrogens to macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W368–W371. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leach AR. Molecular Modelling: Principles and Applications. 2. Pearson Education Limited; Essex: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Allen MP, Tildesley DJ. Computer Simulations of Liquids. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ryckaert JP, Ciccotti G, Berendsen HJC. Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: Molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. Journal of Computational Physics. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim E-H, Rensing C, McEvoy MM. Chaperone-mediated copper handling in the periplasm. Natural Product Reports. 2010;27:711–719. doi: 10.1039/b906681k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frisch MJT, GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JA, Jr, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam NJ, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas Ö, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ. Gaussian 09, Revision A02. Gaussian, Inc; Wallingford CT: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. A new local density functional for main-group thermochemistry, transition metal bonding, thermochemical kinetics, and noncovalent interactions. J Chem Phys. 2006;125:194101. doi: 10.1063/1.2370993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hay PJ, Wadt WR. Ab initio Effective Core Potentials for Molecular Calculations - Potentials for K to Au Including the Outermost Core Orbitals. J Chem Phys. 1985;82:299–310. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ditchfie R, Hehre WJ, Pople JA. Self-Consistent Molecular-Orbital Methods .9. Extended Gaussian-Type Basis for Molecular-Orbital Studies of Organic Molecules. J Chem Phys. 1971;54:724–728. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peters MB, Yang Y, Wang B, Fusti-Molnar L, Weaver MN, Merz KM. Structural Survey of Zinc-Containing Proteins and Development of the Zinc AMBER Force Field (ZAFF) J Chem Theory Comput. 2010;6:2935–2947. doi: 10.1021/ct1002626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Case DA, Darden TA, Cheatham TEI, Simmerling CL, Wang J, Duke RE, Luo R, Walker RC, Zhang W, Merz KM, Roberts B, Wang B, Hayik S, Roitberg A, Seabra G, Kolossvai I, Wong KF, Paesani F, Vanicek J, Liu J, Wu X, Brozell SR, Steinbrecher T, Gohlke H, Cai Q, Ye X, Wang J, Hsieh M-J, Cui G, Roe DR, Mathews DH, Seetin MG, Sagui C, Babin V, Luchko T, Gusarov S, Kovalenko A, Kollman PA. AMBER. Vol. 11. University of California; San Francisco: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor Chem Acc. 2008;120:215–241. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bayly CI, Cieplak P, Cornell WD, Kollman PA. A Well-Behaved Electrostatic Potential Based Method Using Charge Restraints for Deriving Atomic Charges - the RESP Model. J Phys Chem-Us. 1993;97:10269–10280. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cieplak P, Cornell WD, Bayly C, Kollman PA. Application of the Multimolecule and Multiconformational RESP Methodology to Biopolymers - Charge Derivation for DNA, RNA, and Proteins. J Comput Chem. 1995;16:1357–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pierce LCT, Salomon-Ferrer R, de Oliveira CAF, McCammon JA, Walker RC. Routine Access to Millisecond Time Scale Events with Accelerated Molecular Dynamics. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012;8:2997–3002. doi: 10.1021/ct300284c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lindorff-Larsen K, Piana S, Palmo K, Maragakis P, Klepeis JL, Dror RO, Shaw DE. Improved side-chain torsion potentials for the Amber ff99SB protein force field. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics. 2010;78:1950–1958. doi: 10.1002/prot.22711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Case DA, Darden TA, Cheatham TEI, Simmerling CL, Wang J, Duke RE, Luo R, Walker RC, Zhang W, Merz KM, Roberts B, Hayik S, Roitberg A, Seabra G, Swails J, Goetz AW, Kolossvai I, Wong KF, Paesani F, Vanicek J, Wolf RM, Liu J, Wu X, Brozell SR, Steinbrecher T, Gohlke H, Cai Q, Ye X, Wang J, Hsieh M-J, Cui G, Roe DR, Mathews DH, Seetin MG, Salomon-Ferrer R, Sagui C, Babin V, Luchko T, Gusarov S, Kovalenko A, Kollman PA. AMBER. Vol. 12. University of California; San Francisco: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 73.York DM, Darden TA, Pedersen LG. The Effect of Long-Range Electrostatic Interactions in Simulations of Macromolecular Crystals - a Comparison of the Ewald and Truncated List Methods. J Chem Phys. 1993;99:8345–8348. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shen Y, Bax A. SPARTA plus: a modest improvement in empirical NMR chemical shift prediction by means of an artificial neural network. J Biomol Nmr. 2010;48:13–22. doi: 10.1007/s10858-010-9433-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Heinig M, Frishman D. STRIDE: a web server for secondary structure assignment from known atomic coordinates of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W500–W502. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. Journal of Molecular Graphics. 1996;14:33. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Williams T, Kelley C. Gnuplot. 4.4 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Duan LL, Mei Y, Zhang DW, Zhang QG, Zhang JZH. Folding of a Helix at Room Temperature Is Critically Aided by Electrostatic Polarization of Intraprotein Hydrogen Bonds. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:11159–11164. doi: 10.1021/ja102735g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Williams S, Causgrove TP, Gilmanshin R, Fang KS, Callender RH, Woodruff WH, Dyer RB. Fast events in protein folding: Helix melting and formation in a small peptide. Biochemistry. 1996;35:691–697. doi: 10.1021/bi952217p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Uversky VN. A decade and a half of protein intrinsic disorder: Biology still waits for physics. Protein Sci. 2013;22 doi: 10.1002/pro.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chakravorty DK, Wang B, Lee CW, Giedroc DP, Merz KM. Simulations of Allosteric Motions in the Zinc Sensor CzrA. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:3367–3376. doi: 10.1021/ja208047b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chakravorty DK, Wang B, Ucisik MN, Merz KM. Insight into the Cation-pi Interaction at the Metal Binding Site of the Copper Metallochaperone CusF. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:19330–19333. doi: 10.1021/ja208662z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Loftin IR, Franke S, Blackburn NJ, McEvoy MM. Unusual Cu(I)/Ag(I) coordination of Escherichia coli CusF as revealed by atomic resolution crystallography and X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Protein Sci. 2007;16:2287–2293. doi: 10.1110/ps.073021307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xue Y, Davis AV, Balakrishnan G, Stasser JP, Staehlin BM, Focia P, Spiro TG, Penner-Hahn JE, O’Halloran TV. Cu(I) recognition via cation-pi and methionine interactions in CusF. Nature Chemical Biology. 2008;4:107–109. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cram DJ. The Design of Molecular Hosts, Guests, and Their Complexes. Science. 1988;240:760–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Reyes-Caballero H, Campanello GC, Giedroc DP. Metalloregulatory proteins: Metal selectivity and allosteric switching. Biophys Chem. 2011;156:103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Su CC, Long F, Lei HT, Bolla JR, Do SV, Rajashankar KR, Yu EW. Charged Amino Acids (R83, E567, D617, E625, R669, and K678) of CusA Are Required for Metal Ion Transport in the Cus Efflux System. J Mol Biol. 2012;422:429–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.