Abstract

Objective To characterize risk of hypotension requiring admission to hospital in middle aged and older men treated with tamsulosin for benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Design Population based retrospective cohort study (between patient methodology) and self controlled case series (within patient methodology).

Setting Healthcare claims data from the IMS Lifelink database in the United States.

Participants Men aged 40-85 years with private US healthcare insurance entering the cohort at their first dispensing for tamsulosin or for a 5α reductase inhibitor (5ARI) between January 2001 and June 2011after a minimum of six months’ enrolment.

Main outcomes measures Hypotension requiring admission to hospital. Cox proportional hazards models estimated rate ratios at time varying intervals during follow-up: weeks 1-4, 5-8, and 9-12 after tamsulosin initiation; weeks 1-4, 5-8, and 9-12 after restarting tamsulosin (after a four week gap); and maintenance tamsulosin treatment (remaining exposed person time). Covariates included age, calendar year, demographics, antihypertensive use, healthcare use, and a Charlson comorbidity score. A self controlled case series, having implicit control for time invariant covariates, was additionally conducted.

Results Among 383 567 new users of study drugs (tamsulosin 297 596; 5ARI 85 971), 2562 admissions to hospital for severe hypotension were identified. The incidence for hypotension was higher for tamsulosin (42.4 events per 10 000 person years) than for 5ARIs (31.3 events per 10 000 person years) or all accrued person time (29.1 events per 10 000 person years). After tamsulosin initiation, the cohort analysis identified an increased rate of hypotension during weeks 1-4 (rate ratio 2.12 (95% confidence interval 1.29 to 3.04)) and 5-8 (1.51 (1.04 to 2.18)), and no significant increase at weeks 9-12. The rate ratio for hypotension also increased at weeks 1-4 (1.84 (1.46 to 2.33)) and 5-8 (1.85 (1.45 to 2.36)) after restarting tamsulosin, as did maintenance tamsulosin treatment (1.19 (1.07 to 1.32)). The self controlled case series gave similar results as the cohort analysis.

Conclusions We observed a temporal association between tamsulosin use for benign prostatic hyperplasia and severe hypotension during the first eight weeks after initiating treatment and the first eight weeks after restarting treatment. This association suggests that physicians should focus on improving counseling strategies to warn patients regarding the “first dose phenomenon” with tamsulosin.

Introduction

Benign prostatic hyperplasia is an enlargement of the transition zone of the prostate that can cause lower urinary tract symptoms and could lead to bladder outlet obstruction in men. Lower urinary tract symptoms can include urinary frequency, urgency, hesitancy, or nocturia, and can result in a marked decrease in quality of life. It has been estimated that 50% of men in the United States over the age of 50 have this condition.1

First line medical treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia consists of α1 adrenergic receptor antagonists (α blockers) and 5α reductase inhibitors (5ARI). α blockers relieve bladder outlet obstruction by relaxing the periurethral prostatic smooth muscle and allowing for improved urinary flow. 5ARIs have shown to reduce disease progression, prevent complications from benign prostatic hyperplasia (including acute urinary retention and prostate related surgery), and improve lower urinary tract symptoms starting after six months of treatment.2 Although effective, when initiated, α blockers can induce marked orthostatic hypotension and syncope.3 This effect was labeled the “first dose phenomenon” by Bendall and colleagues in men using prazosin in 1975,4 and subsequently has been reported in antagonists to the α1 adrenergic receptor, terazosin and doxazosin.5 This effect is a consequence of inadvertent vasodilation and a decrease in systemic vascular resistance. A recent study found an increased risk of hip fracture among men taking α blockers but not 5ARIs, suggesting that it may have resulted from an increased risk of hypotension induced falls.6 Tamsulosin is a uroselective α blocker owing to its selectivity as an α1a receptor antagonist, which is the predominant receptor that mediates prostate smooth muscle tension.7 Compared to non-selective α1 blockers such as terazosin and doxazosin, tamsulosin has a lower rate of asthenia, dizziness, and severe hypotension in clinical trials.8 As a result, it has a warning for hypotension and syncope, but not a black box warning similar to less selective α blockers in its class.

It is unknown whether tamsulosin treatment induces a first dose phenomenon in clinical practice and confers increased risk for hypotension, requiring admission to hospital immediately after initiating or restarting drug treatment. Our study aimed to characterize the risk of severe hypotension at time varying intervals during the course of tamsulosin treatment in middle aged and older men with benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Methods

Data source

The IMS Lifelink database contains paid claims from over 102 healthcare plans in the US. It contains fully adjudicated medical and pharmacy claims for over 68 million patients, including inpatient and outpatient diagnoses and procedures (International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM)) in addition to retail and mail order prescription records. Compared with the US census, the database captures 16% of men aged 35-44, 17% aged 45-54, 13% aged 55-64, and 8% aged 65 years and older. Men over 65 years of age are captured through Medicare Advantage, a privatized healthcare plan where recipients pay extra to improve basic Medicare coverage. This plan combines healthcare and prescription services (without the gap in coverage in Medicare part D) to provide healthcare coverage that is generally more inclusive than general Medicare (parts A and B) and Medicare part D services. The Lifelink database is subject to quality checks to ensure data quality and minimize error rates.9 This database has been used in previous pharmacoepidemiological studies.10 11 12

Study participants

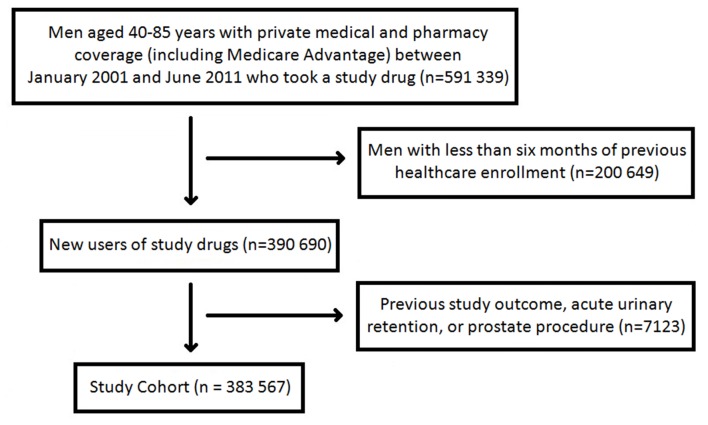

We identified men aged 40-85 years with demonstration of prescription and medical coverage between 1 January 2001 and 30 June 2011. To identify men naive to treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia, new users of α blockers and 5ARIs were identified as patients with no use of any drug treatment from either therapeutic classification during a six month baseline period. Cohort index date was the first dispensing for a study drug. Men were excluded if they were admitted to hospital with hypotension during the six month baseline period. We also excluded patients with a previous transurethral resection of the prostate, transurethral microwave thermotherapy, simple prostatectomy, or an episode of acute urinary retention to capture a more homogenous population with less advanced benign prostatic hyperplasia. Censoring occurred at the end of enrolment, at the end of the study period, or after the study outcome. Fig 1 shows formation of the study cohort.

Fig 1 Study cohort development

Drug exposure

Tamsulosin was our study drug of interest because it comprised the majority of total use of α blockers in our data. Other α blockers are approved for benign prostatic hyperplasia, including alfuzosin, doxazosin, silodosin, and terazosin. Silodosin (Rapaflo), alfuzosin (Uroxatral), and doxazosin extended release (Cardura XL) were ignored because their use in our study population was minimal. Furthermore, low use makes adverse events with these specific drugs less of a public health concern. We excluded terazosin (Hytrin, Zayasel) and doxazosin (Cardura) because they are also indicated for hypertension, the requirement for a diagnosis of benign prostatic hyperplasia before initiating drug treatment resulted in too few exposed person years for analysis, and confounding by a coindication for benign prostatic hyperplasia and hypertension could impose bias. Exposure to 5ARIs including finasteride (Proscar) and dutasteride (Avodart) were also identified during longitudinal follow-up. Finasteride (Propecia) was ignored because this formulation is taken at a lower dose (1 mg daily), had low use, and is approved only for androgenic alopecia. Inclusion of men initiating 5ARIs formed a reference comparator of men initiating new, non-tamsulosin drug treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia, and it set time since initiation of treatment as the underlying time scale in our analysis.

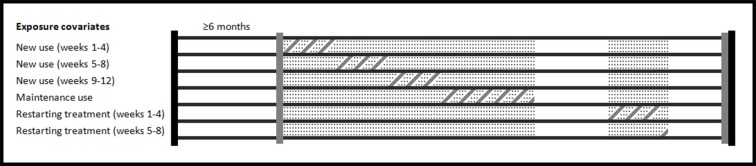

Patients were considered exposed to study drugs from the dispensing date until the end of day supply. We used time varying definitions for drug exposure for all analyses, allowing patients to fluctuate between exposure classifications or contribute time to multiple exposure categories simultaneously depending on prescribing patterns. As conducted by a previous study,13 we formed a discrete time dataset for computational efficiency, where follow-up time was segmented into seven day increments. For each increment, one of seven exposure classifications was assigned for tamsulosin based on the majority of exposed days during the week. Mutually exclusive classifications for exposure were as follows: weeks 1-4, 5-8, and 9-12 after drug initiation; weeks 1-4, 5-8, and 9-12 after restarting treatment (after a four week treatment gap); and maintenance drug use (that is, exposed person time not categorized as another exposure covariate). This methodology for exposure categorization allowed us to explicitly model risk for the study outcome within set risk windows during the course of drug treatment, and it has been used in a previous pharmacoepidemiological study.14 Figure 2 shows person time allocation among exposure covariates.

Fig 2 Person time allocation for drug exposure covariates. Schematic shows an example characterization of person time into exposure covariates for a given patient. Included person time starts at initiation of drug treatment and ends when healthcare eligibility finishes. The patient in this schematic contributes person time to three new use covariates, maintenance use, and two restarting exposure covariates. Dotted regions=actual exposed person time; diagonal line regions=attribution of person time to exposure covariates; vertical black lines=enrolment eligibility; vertical grey lines=exposure assessment; horizontal black lines=differentiates between depiction of exposure covariates along longitudinal patient time

Outcome ascertainment

Our outcome was severe hypotension requiring hospital admission. The outcome was ascertained as a primary hospital discharge diagnosis of hypotension (ICD-9-CM codes 458.0, 458.1, or 458.9). This algorithm has been used in a previous study,15 the event was considered to occur on the first day of admission to hospital, and the ascertainment can be considered validated as a falsification endpoint.16

Cohort analysis

Cohort analyses were conducted using Cox proportional hazards models to form a hazard ratio to estimate the rate ratio for hospital admission with severe hypotension. Baseline enrolment covariates included US geographical region (east, midwest, south, or west) and insurance type (Medicare Advantage or Private Healthcare Maintenance Organization). We also assessed three additional baseline covariates during the six months before cohort entry: number of physician visits, number of prescriptions dispensed, and a Charlson comorbidity score. This score includes assessment for myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, rheumatic disease, peptic ulcer disease, mild liver disease, diabetes with and without chronic complications, hemiplegia or paraplegia, renal disease, malignancy (except neoplasm of the skin), metastatic solid tumors, and HIV/AIDS. These covariates were shown to be independent predictors of one year mortality in a study by Charlson and colleagues, and the score is formed by weighting the presence of each covariate by the reported relative risks for one year mortality.17 18

Calendar year (to adjust for secular patterns in drug prescribing) and patient age were both defined as time varying covariates at each seven day increment. We further defined time varying exposures to β blockers, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, and thiazide diuretics to adjust for effects of concomitant antihypertensive treatment on our study outcome.

The study analysis modeled the rate ratio for hypotension with all time varying categorizations of tamsulosin exposure and study covariates in the same model. The reference comparator for each tamsulosin exposure covariate consisted of all person time contributed by patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia unexposed to that covariate and still at risk for developing the study outcome. Proportionality of hazards was assessed after baseline for each exposure covariate using the log-log survival curve.

Self controlled case series analysis

A secondary analysis was conducted for all patients included in the study cohort who had a hospital admission for hypotension, using a self controlled case series analysis. Because it is a within patient design, the self controlled case series is not confounded by covariates that do not change over time (that is, covariates that are time invariant). Such covariates include demographics and measured or unmeasured long term disease states such as benign prostatic hyperplasia or hypertension and their multiplicative interactions. This modeling approach uses conditional Poisson regression to assess the association between a time varying exposure and an acute outcome using data from only the cases.19 An incidence rate ratio is calculated, comparing the incidence of study outcomes during time exposed with time unexposed to drug exposure covariates within each patient. It is ideal with an acute outcome (for example, admission to hospital) and transient drug exposure covariates (that is, a short ratio of risk window length to total enrolment length).20

The self controlled case series has three main implied assumptions.21 Firstly, if a study outcome perturbs future drug exposure, this could impose immortal time bias whereby the incidence for the outcome may be lower before initiating drug treatment.22 Potential bias from a violation of this assumption was circumvented by starting longitudinal follow-up at the initiation of a study drug exposure.19 Censoring occurred at the end of enrolment or the end of the study period, but not at a study outcome because this can impose bias.22 Secondly, the self controlled case series design assumes an underlying Poisson distribution of events, where a study outcome does not influence a future outcome. This was dealt with through a sensitivity analysis that modeled only the first event, assuming subsequent outcomes are a continuation of the first outcome occurrence. Thirdly, the self controlled case series design assumes that a study outcome does not censor patient follow-up. Although methods have been derived to analyze event dependent censoring,23 24 our study outcome is not likely fatal and will rarely censor follow-up.

All time varying exposure covariates from the cohort analysis were included in this modeling approach. Exposure covariates were defined in seven day increments to maintain uniform exposure classification to the cohort analysis, and age and calendar year were adjusted for as continuous parametric variables defined during each seven day window. We did a sensitivity analysis, adjusting for age in five year brackets to allow the underlying incidence for hypotension to vary by age; we similarly adjusted for calendar year in one year increments throughout follow-up. All analyses were conducted using Statistical Analysis Software 9.3.

Results

We identified 297 596 new users of tamsulosin and 85 971 new users of 5ARIs with a mean age of 62 and 64 years, respectively. During follow-up, 26 659 patients switched to or initiated new adjunct treatment with tamsulosin, while 47 628 patients switched to or initiated new adjunct treatment with 5ARIs. Mean duration of tamsulosin treatment was 39 weeks (standard deviation 54 weeks) while median duration was 14 weeks (interquartile range 5-50 weeks); mean duration of 5ARI treatment was 56 weeks (61 weeks) while median duration was 34 weeks (13-78 weeks). Table 1 shows patient characteristics.

Table 1.

Cohort demographics according to exposure to α blocker

| Tamsulosin | 5ARI | |

|---|---|---|

| Study drug exposure | ||

| Number of patients exposed | 324 255 | 133 599 |

| Cumulative exposure (weeks, median (IQR)) | 14 (5-50) | 34 (13-78) |

| Baseline covariates* | ||

| Physician visits | ||

| 0 | 46 526 (14.4) | 16 918 (12.7) |

| 1-5 | 127 171 (39.2) | 53 314 (39.9) |

| ≥6 | 150 558 (46.4) | 63 367 (47.4) |

| Previous drug treatments | ||

| 1-6 | 64 241 (19.8) | 26 512 (19.8) |

| 7-18 | 94 722 (29.2) | 43 193 (32.3) |

| ≥19 | 165 292 (51.0) | 63 894 (47.9) |

| Charlson comorbidity score | ||

| 0 | 207 451 (64.0) | 91 635 (68.6) |

| 1-5 | 111 845 (34.5) | 40 654 (30.4) |

| ≥6 | 4 959 (1.5) | 1 310 (1.0) |

| US geographical location | ||

| East | 66 309 (20.5) | 30 475 (22.8) |

| Midwest | 97 499 (30.1) | 39 338 (29.4) |

| South | 121 217 (37.3) | 46 729 (35.0) |

| West | 39 230 (12.1) | 17 057 (12.8) |

| Healthcare insurer | ||

| Private Healthcare Maintenance Organization | 284 477 (87.7) | 114 944 (86.0) |

| Medicare Advantage | 39 778 (12.3) | 18 655 (14.0) |

| Time varying covariates† | ||

| Age at cohort entry (years; mean (SD)) | 62 (10) | 64 (10) |

| β blocker use | 101 953 (31.4) | 43 147 (32.4) |

| Calcium blocker use | 67 324 (20.8) | 29 636 (22.2) |

| Thiazide diuretic use | 76 502 (23.6) | 33 912 (25.4) |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB use | 141 620 (43.7) | 61 488 (46.0) |

Data are number (%) of patients unless stated otherwise. IQR=interquartile range; SD=standard deviation; ACE=angiotension converting enzyme; ARB=angiotensin receptor blocker.

*Defined during the six month baseline period before new drug use.

†Adjusted for as time varying covariates in study models, updated in each seven day increment.

In the primary cohort analysis, 2562 hypotension events were observed during 880 770 total person years of follow-up (29.1 events per 10 000 person years). The incidence for hypotension in patients taking 5ARIs was similar to that of the overall cohort (451 events, 144 309 person years; 31.3 events per 10 000 person years). During 240 276 person years exposed to tamsulosin, 1018 events were observed, producing an empirically larger incidence (42.4 events per 10 000 person years).

The cohort approach observed a 2.12 times increased rate ratio for severe hypotension during weeks 1-4 after initiating tamsulosin treatment (95% confidence interval 1.29 to 3.04). Elevated risk was observed during weeks 5-8 after tamsulosin initiation (rate ratio 1.51, 95% confidence interval 1.04 to 2.18) but not during weeks 9-12 (1.16, 0.83 to 1.61). After restarting drug treatment, we observed a similar increase in risk during weeks 1-4 (1.84, 1.46 to 2.33) and weeks 5-8 (1.85, 1.45 to 2.36), although the risk increase during weeks 9-12 was not significant (1.34, 0.97 to 1.84). Maintenance treatment had a smaller but significantly increased risk for hypotension (1.19, 1.07 to 1.32). Table 2 shows all results from the cohort analysis.

Table 2.

Hypotension rates with tamsulosin, according to risk window of exposure and between and within patient methodology

| No of men | No of events | No of person years | Rate of hypotension per 10 000 person years* | Rate ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Cohort analysis | |||||

| New use (weeks 1-4) | 324 255 | 179 | 22 950 | 78.0 | 2.12 (1.29 to 3.04) |

| New use (weeks 5-8) | 278 283 | 74 | 15 116 | 49.0 | 1.51 (1.04 to 2.18) |

| New use (weeks 9-12) | 174 599 | 63 | 14 373 | 43.8 | 1.16 (0.83 to 1.61) |

| Restarting treatment (weeks 1-4) | 103 145 | 74 | 14 641 | 50.5 | 1.84 (1.46 to 2.33) |

| Restarting treatment (weeks 5-8) | 96 630 | 69 | 13 271 | 52.0 | 1.85 (1.45 to 2.36) |

| Restarting treatment (weeks 9-12) | 77 418 | 39 | 10 398 | 37.5 | 1.34 (0.97 to 1.84) |

| Maintenance treatment | 151 307 | 520 | 149 527 | 34.8 | 1.19 (1.07 to 1.32) |

| Model 2: Self controlled case series | |||||

| New use (weeks 1-4) | 2248 | 185 | 167 | 110.8 | 2.56 (2.15 to 3.05) |

| New use (weeks 5-8) | 2076 | 79 | 118 | 67.2 | 1.66 (1.30 to 2.11) |

| New use (weeks 9-12) | 1404 | 68 | 116 | 58.6 | 1.54 (1.19 to 2.01) |

| Restarting treatment (weeks 1-4) | 1104 | 80 | 181 | 44.2 | 1.58 (1.24 to 2.01) |

| Restarting treatment (weeks 5-8) | 1070 | 74 | 172 | 43.0 | 1.60 (1.25 to 2.05) |

| Restarting treatment (weeks 9-12) | 912 | 42 | 133 | 31.6 | 1.19 (0.86 to 1.64) |

| Maintenance treatment | 1357 | 651 | 1923 | 33.9 | 1.38 (1.21 to 1.57) |

*Incidence of hypotension for the cohort represents absolute incidence in the study population, while incidence in the self controlled case series represents relative incidence in the cases.

The self controlled case series confirmed the finding for increased hypotension risk during weeks 1-4 of new use (rate ratio 2.56, 95% confidence interval 2.15 to 3.05; table 2). Weeks 5-8 (1.66, 1.30 to 2.11) and 9-12 (1.54, 1.19 to 2.01) after starting new drug treatment also showed an increase in hypotension risk. After restarting treatment, weeks 1-4 (1.58, 1.24 to 2.01) and 5-8 (1.60, 1.25 to 2.05) observed increased risk for hypotension, as did maintenance drug treatment (1.38, 1.21 to 1.57). Sensitivity analyses, with the self controlled case series limiting the analysis to only one event and semi-parametrically adjusting for age and calendar time, found similar results (web appendix).25

Discussion

We observed an increased rate ratio for severe hypotension requiring admission to hospital with tamsulosin treatment. The greatest increase in risk—varying in magnitude from 151% to 256%—was observed during the first eight weeks of new drug use and the first eight weeks after restarting drug treatment. A smaller increase in risk for hypotension, varying from 19% to 36%, persisted during maintenance tamsulosin treatment.

Antagonism of α1 adrenoreceptors by tamsulosin relaxes the smooth muscles in the bladder neck and prostate to improve urine flow rate and symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Although hypertension is not an approved indication for tamsulosin, α blockers are also known to decrease systemic vascular resistance and reduce blood pressure. Clinical trials observed a 12% incidence for orthostatic hypotension among patients taking 0.4 mg tamsulosin, and a 6% incidence among patients taking placebo between four to eight hours after dosing; however, no treatment emergent hypotensive events were observed.26 In these trials, patients were retained at the treating site for eight hours after the first dose and received counseling on the effects of orthostatic hypotension. This environment may not apply to treatment practice in the real world. Three currently approved selective α1 adrenergicantagonists (doxazosin, prazosin, terazosin) have black boxed warnings for severe hypotension and syncope, particularly at the first dose. Tamsulosin has a warning for hypotension, but without a black box or information on a potential first dose phenomenon. Our data add to the current literature to better define and quantify the first dose phenomenon of tamsulosin on risk for hypotension.

Comparison with other studies

A study in the US Food and Drug Administration’s adverse events reporting system used data mining strategies of spontaneous reports to assess potential safety signals with α adrenergic antagonists.27 Concern for dizziness or vertigo and orthostatic hypotension were raised for tamsulosin in addition to alfuzosin, doxazosin, and terazosin. A recent Cochrane review also found higher rates of dizziness with larger tamsulosin dosages (0.8 mg, 17% dizziness; 0.4 mg, 9%; 0.2 mg, 3%), suggesting a dose dependent effect.28

In a prospective cohort study of 5872 participants, Parsons and colleagues found a significantly increased risk of falls at one year in community dwelling men aged 65 years and older with moderate or severe lower urinary tract symptoms, based on the validated American Urological Association symptom index.29 But they did not find any difference when stratifying patients on the basis of use of urological drug treatments. However, all urological drugs were grouped together in the analysis (α blockers, 5ARIs, anticholinergics), and more importantly, drug use was only collected at baseline—therefore, a first dose phenomenon could not be assessed. The population based case-control study by Jacobsen and colleagues found an increased risk of hip fractures among men with benign prostatic hyperplasia taking α blockers but not 5ARIs.6 Notably, this risk was only observed in men initiating treatment with an α blocker within 30 days (odds ratio 2.04, 95% confidence interval 1.19 to 3.49). Our study suggests that this increased risk of hip fractures with α blockers use could be secondary to falls as a result of severe hypotensive events at initiation.

Strengths and limitations of this study

In our analysis, exposure risk windows demonstrated utility for identifying time varying risk for hypotension at drug initiation and restart. Resultant rate ratios must be interpreted within the context of prescribing practice: rate ratios for hypotension in later study risk windows (for example, weeks 5-8, 9-12) represent hypotension risk among patients who probably tolerated earlier risk windows of exposure (for example, weeks 1-4) without having a hypotension event that led to hospital admission. Patients compliant with tamsulosin treatment may also achieve better control of lower urinary tract symptoms, which could result in a lower risk of falls,29 supporting the importance of optimizing drug adherence.

We did not have access to information on ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or lifestyle factors in our data. Residual confounding is always possible in observational studies. However, the close temporality of hypotension risk to initiation of drug treatment and a secondary self controlled analysis that implicitly controlled for time invariant confounders suggested that the bias due to measurement error in the confounders could be minimal or absent. Because our data captured men with private healthcare insurance (including Medicare Advantage), generalisability to men older than 65 years with traditional Medicare and part D services is unknown. Our outcome was a severe hypotension episode, probably resulting from syncope, and requiring admission to hospital. Although many patients will have a clinically relevant drop in blood pressure (orthostatic hypotension), our outcome was not intended to capture these changes in blood pressure, but rather only treatment emergent events. Further, although larger tamsulosin doses could have shown a greater hypotension risk, infrequent use of doses other than 0.4 mg once daily in our data prevented analysis of this potential effect.

A comparison of hypotension risk with tamsulosin to other α blockers would be of clinical interest, but low use of other α blockers for benign prostatic hyperplasia and confounding by a coindication for hypertension would decrease interpretability of this comparison. In our study, we used two analytical techniques to increase robustness of our study results. The magnitude of the point estimates were not completely synonymous using the cohort and self controlled case series approaches, particularly with regards to weeks 9-12 of new tamsulosin use. These differences are probably attributable to differences in the underlying number of person years in each risk window of exposure among all patients (cohort analysis) versus only those who experienced outcomes (self controlled case series analysis), and to differences in the reference comparator for these techniques. However, both analyses agreed on time varying risks of larger magnitude at new use and restarting tamsulosin treatment than observed with maintenance treatment. Future work is needed to determine whether genetic characteristics or other non-measured risk factors may modify susceptibility to hypotension with tamsulosin.

What is already known on this topic

α adrenergic antagonists increase the risk of dizziness and orthostatic hypotension

It is unknown whether tamsulosin, a selective α1a receptor antagonist, will increase risk of hypotension needing hospital admission and show a “first dose phenomenon” similar to non-selective α antagonists

What this study adds

Tamsulosin resulted in a roughly doubled risk for hypotension needing hospital admission during the first eight weeks after tamsulosin initiation and first eight weeks after restarting tamsulosin treatment

Physicians should focus on improving counselling strategies to warn patients regarding the first dose phenomenon with tamsulosin and to promote optimal drug adherence

This study represents the opinions of the authors and not those of the Food and Drug Administration.

Contributors: All authors took part in the study design and the analysis and interpretation of the data. The manuscript was drafted by STB and critically revised for important intellectual content by all authors. STB had full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors approved the final manuscript for publication. AGH is the study guarantor.

Funding: This work was funded in part by the McGill University Health Center, Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec, and the Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux. The authors had full autonomy in the study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the article; and the decision to submit it for publication. The authors have no other conflicts or competing interests to declare.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: support from the McGill University Health Center, Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec, and the Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux for the submitted work; JMB has received peer review financial support from le Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec, JACD has a research grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, AGH is a principal investigator for the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership, a private-public partnership designed to help improve drug safety monitoring, and STB is employed by the US Food and Drug Administration; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the University of Florida institutional review board (180-2012).

Data sharing: Based on our third party access agreement for the data with IMS and IRB restrictions, no additional data available.

STB affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;347:f6320

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Web appendix: Sensitivity analyses

References

- 1.Black L, Naslund MJ, Gilbert TD Jr, Davis EA, Ollendorf DA. An examination of treatment patterns and costs of care among patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Am J Manag Care 2006;12(4 suppl):S99-110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Urological Association. Chapter 1: Guideline on the management of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). In: Management of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Revised, 2010. www.auanet.org/common/pdf/education/clinical-guidance/Benign-Prostatic-Hyperplasia.pdf.

- 3.Nash DT. Alpha-adrenergic blockers: mechanism of action, blood pressure control, and effects of lipoprotein metabolism. Clin Cardiol 1990;13:764-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bendall MJ, Baloch KH, Wilson PR. Side effects due to treatment of hypertension with prazosin. BMJ 1975;2:727-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfizer Pharmaceuticals. Cardura [package insert]. Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, 2010.

- 6.Jacobsen SJ, Cheetham TC, Haque R, Shi JM, Loo RK. Association between 5-alpha reductase inhibition and risk of hip fracture. JAMA 2008;300:1660-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forray C, Bard JA, Wetzel JM, Chiu G, Shapiro E, Tang R, et al. The alpha 1-adrenergic receptor that mediates smooth muscle contraction in human prostate has the pharmacological properties of the cloned human alpha 1c subtype. Mol Pharmacol 1994;45:703-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Provider Synergies. Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) treatments review. 2010. www.oregon.gov/OHA/pharmacy/therapeutics/docs/ps-2010-03-bph.pdf.

- 9.IMS Health. LifeLink health plan claims database: overview and study design issues. 2010. www.uams.edu/TRI/hsrcore/Lifelink_Health_Plan_Claims_Data_DesignIssues_wcost_April2010.pdf.

- 10.Bird ST, Etminan M, Brophy JM, Hartzema AG, Delaney JA. Risk of acute kidney injury associated with the use of fluoroquinolones. CMAJ 2013;185:E475-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jick SS, Hernandez RK. Risk of non-fatal venous thromboembolism in women using oral contraceptives containing drospirenone compared with women using oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel: case-control study using United States claims data. BMJ 2011;342:d2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stafford RS, Furberg CD, Finkelstein SN, Cockburn IM, Alehegn T, Ma J. Impact of clinical trial results on national trends in alpha-blocker prescribing, 1996-2002. JAMA 2004;291:54-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winterstein AG, Gerhard T, Kubilis P, Saidi A, Linden S, Crystal S, et al. Cardiovascualr safety of central nervous system stimulants in children and adolescents: population based cohort study. BMJ 2012;345:e4627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Douglas IJ, Langham J, Bhaskaran K, Brauer R, Smeeth L. Orlistat and the risk of acute liver injury: self controlled case series studies in UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink. BMJ 2013;346:f1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright AJ, Gomes T, Mamdani MM, Horn JR, Juurlink DN. The risk of hypotension following co-prescription of macrolide antibiotics and calcium-channel blockers. CMAJ 2011;183:303-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prasad V, Jena AB. Prespecified falsification end points: can they validate true observational associations? JAMA 2013;309:241-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitaker HJ, Farrington CP, Spiessens B, Musonda P. Tutorial in biostatistics: the self-controlled case series method. Stat Med 2006;25:1768-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whitaker HJ, Hocine MN, Farrington CP. The methodology of self-controlled case series studies. Stat Methods Med Res 2009;18:7-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitaker HJ, Hocine MN, Farrington CP. On case-crossover methods for environmental time series data. Environmetrics 2007;18:157-71. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maclure M, Fireman B, Nelson JC, Hua W, Shoaibi A, Paredes A, et al. When should case-only designs be used for safety monitoring of medical products? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21(S1):50-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farrington CP, Whitaker HJ, Hocine MN. Case series analysis for censored, perturbed, or curtailed post-event exposures. Biostatistics 2009;10:3-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farrington CP, Anaya K, Whitaker HJ, Hocine MN, Douglas I, Smeeth L. Self-controlled case series analysis with event-dependent observation periods. JASA 2011;106:417-26. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farrington CP, Whitaker HJ. Semiparametric analysis of case series data. Appl Statist 2006;55:553-94. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medical Approval Review. Flomax capsules, 0.4mg; NDA 20579. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. 1997.

- 27.Yoshimura K, Kadoyama K, Sakaeda T, Sugino Y, Ogawa O, Okuno Y. A Survey of the FAERS database concerning the adverse event profiles of α1-adrenoreceptor blockers for lower urinary tract symptoms. Int J Med Sci 2013;10:864-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilt T, MacDonald R, Rutks I. Tamsulosin for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;4:CD002081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parsons JK, Mougey J, Lambert L, Wilt TJ, Fink HA, Garzotto M, et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms increase the risk of falls in older men. BJU Int 2009;104:63-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Sensitivity analyses