Abstract

Background

Specialized community-based care (SCBC) endeavours to help patients manage chronic diseases by formalizing the link between primary care providers and other community providers with specialized training. Many types of health care providers and community-based programs are employed in SCBC. Patient-centred care focuses on patients’ psychosocial experience of health and illness to ensure that patients’ care plans are modelled on their individual values, preferences, spirituality, and expressed needs.

Objectives

To synthesize qualitative research on patient and provider experiences of SCBC interventions and health care delivery models, using the core principles of patient-centredness.

Data Sources

This report synthesizes 29 primary qualitative studies on the topic of SCBC interventions for patients with chronic conditions. Included studies were published between 2002 and 2012, and followed adult patients in North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand.

Review Methods

Qualitative meta-synthesis was used to integrate findings across primary research studies.

Results

Three core themes emerged from the analysis:

patients’ health beliefs affect their participation in SCBC interventions;

patients’ experiences with community-based care differ from their experiences with hospital-based care;

patients and providers value the role of nurses differently in community-based chronic disease care.

Limitations

Qualitative research findings are not intended to generalize directly to populations, although meta-synthesis across several qualitative studies builds an increasingly robust understanding that is more likely to be transferable. The diversity of interventions that fall under SCBC and the cross-interventional focus of many of the studies mean that findings might not be generalizable to all forms of SCBC or its specific components.

Conclusions

Patients with chronic diseases who participated in SCBC interventions reported greater satisfaction when SCBC helped them better understand their diagnosis, facilitated increased socialization, provided them with a role in managing their own care, and assisted them in overcoming psychological and social barriers.

Plain Language Summary

More and more, to reduce bed shortages in hospitals, health care systems are providing programs called specialized community-based care (SCBC) to patients with chronic diseases. These SCBC programs allow patients with chronic diseases to be managed in the community by linking their family physicians with other community-based health care providers who have specialized training. This report looks at the experiences of patients and health care providers who take part in SCBC programs, focusing on psychological and social factors. This kind of lens is called patient-centred. Three themes came up in our analysis:

patients’ health beliefs affect how they take part in SCBC interventions;

patients’ experiences with care in the community differ from their experiences with care in the hospital;

patients and providers value the role of nurses differently.

The results of this analysis could help those who provide SCBC programs to better meet patients’ needs.

Background

In July 2011, the Evidence Development and Standards (EDS) branch of Health Quality Ontario (HQO) began developing an evidentiary framework for avoidable hospitalizations. The focus was on adults with at least 1 of the following high-burden chronic conditions: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), coronary artery disease (CAD), atrial fibrillation, heart failure, stroke, diabetes, and chronic wounds. This project emerged from a request by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care for an evidentiary platform on strategies to reduce avoidable hospitalizations.

After an initial review of research on chronic disease management and hospitalization rates, consultation with experts, and presentation to the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee (OHTAC), the review was refocused on optimizing chronic disease management in the outpatient (community) setting to reflect the reality that much of chronic disease management occurs in the community. Inadequate or ineffective care in the outpatient setting is an important factor in adverse outcomes (including hospitalizations) for these populations. While this did not substantially alter the scope or topics for the review, it did focus the reviews on outpatient care. HQO identified the following topics for analysis: discharge planning, in-home care, continuity of care, advanced access scheduling, screening for depression/anxiety, self-management support interventions, specialized nursing practice, and electronic tools for health information exchange. Evidence-based analyses were prepared for each of these topics. In addition, this synthesis incorporates previous EDS work, including Aging in the Community (2008) and a review of recent (within the previous 5 years) EDS health technology assessments, to identify technologies that can improve chronic disease management.

HQO partnered with the Programs for Assessment of Technology in Health (PATH) Research Institute and the Toronto Health Economics and Technology Assessment (THETA) Collaborative to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the selected interventions in Ontario populations with at least 1 of the identified chronic conditions. The economic models used administrative data to identify disease cohorts, incorporate the effect of each intervention, and estimate costs and savings where costing data were available and estimates of effect were significant. For more information on the economic analysis, please contact either Murray Krahn at murray.krahn@theta.utoronto.ca or Ron Goeree at goereer@mcmaster.ca.

HQO also partnered with the Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis (CHEPA) to conduct a series of reviews of the qualitative literature on “patient centredness” and “vulnerability” as these concepts relate to the included chronic conditions and interventions under review. For more information on the qualitative reviews, please contact Mita Giacomini at giacomin@mcmaster.ca.

The Optimizing Chronic Disease Management in the Outpatient (Community) Setting mega-analysis series is made up of the following reports, which can be publicly accessed at http://www.hqontario.ca/evidence/publications-and-ohtac-recommendations/ohtas-reports-and-ohtac-recommendations.

Optimizing Chronic Disease Management in the Outpatient (Community) Setting: An Evidentiary Framework

Discharge Planning in Chronic Conditions: An Evidence-Based Analysis

In-Home Care for Optimizing Chronic Disease Management in the Community: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Continuity of Care: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Advanced (Open) Access Scheduling for Patients With Chronic Diseases: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Screening and Management of Depression for Adults With Chronic Diseases: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Self-Management Support Interventions for Persons With Chronic Diseases: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Specialized Nursing Practice for Chronic Disease Management in the Primary Care Setting: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Electronic Tools for Health Information Exchange: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Health Technologies for the Improvement of Chronic Disease Management: A Review of the Medical Advisory Secretariat Evidence-Based Analyses Between 2006 and 2011

Optimizing Chronic Disease Management Mega-Analysis: Economic Evaluation

How Diet Modification Challenges Are Magnified in Vulnerable or Marginalized People With Diabetes and Heart Disease: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis

Chronic Disease Patients’ Experiences With Accessing Health Care in Rural and Remote Areas: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis

Patient Experiences of Depression and Anxiety With Chronic Disease: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis

Experiences of Patient-Centredness With Specialized Community-Based Care: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis

Objective of Analysis

To synthesize qualitative research on patient and provider experiences of specialized community-based care (SCBC) interventions and health care delivery models, using the lens of patient-centredness.

Clinical Need and Target Population

Chronic Disease

As described in the 2012 Health Quality Ontario (HQO) report Specialized Community-Based Care: An Evidence-Based Analysis, “Chronic diseases have a large impact on the Ontario population. An estimated 1 in 3 Ontarians has a chronic disease, and among those over 65 years of age, 80% have at least 1 chronic disease and 70% have 2 or more chronic diseases. Chronic diseases include heart failure, diabetes, cancer, COPD, and arthritis. In 2002, the World Health Organization estimated that medical treatment for chronic diseases and the resulting lost productivity would cost $80 million in Canada annually.” (1)

Patient-Centredness

The concept of patient-centredness originated in general practice and primary care in the 1970s as a reaction to the prevailing biomedical model of care, which focused on the biologic manifestations of disease rather than on the patient’s psychosocial experience of health and illness. (2) The term patient-centred was coined in 1988. (3) The ideal of patient-centredness entails modelling patients’ care plans on their values, preferences, spirituality, and expressed needs. (2-4) The concept of patient-centredness draws attention to and critiques the patient-provider relationship, promoting nonpaternalistic, nonauthoritarian relationships in which patients’ autonomy is sufficiently empowered so they can participate actively in their own care, and ensuring that their relationships with others (family, supports) are recognized by health care providers. (4-6) To enable this, relevant information should be shared between providers and patients, and decision-making should be collaborative.

Qualitative research has been advocated as the method of choice for investigating both the nonmedical and individualized illness experience, and the experiences of providers in patient-provider relationships. (2) The core principles of patient-centredness that have emerged from the qualitative literature are as follows:

recognizing the cultural, social, and psychological (nonmedical) dimensions of illness;

requiring an understanding of patients’ unique experiences;

promoting a nonpaternalistic, nonauthoritarian relationship between patient and provider;

ensuring agreement on goals and treatment, and a bond of caring and sympathy between providers and patients;

acknowledging providers as persons, necessitating self-awareness of their emotional and cultural responses;

Technique

This meta-synthesis uses the definition of SCBC provided in the 2012 HQO report on SBSC: care “that manages chronic illness through formalized links between primary and specialized care.” (1) Specialized community-based care seeks to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of chronic disease care using interdisciplinary care teams such as primary care physicians, specialists, nurses, dietitians, pharmacists, social workers, caregivers, patients, and physiotherapists. Many terms have been used to describe programs that include the essential elements of SCBC, including intermediate care, shared care, integrated care, chronic disease management, interdisciplinary primary care, collaborative care, guided care, and care-and-case management.

Evidence-Based Analysis

Research Question

What are the findings of the qualitative research on patient and provider experiences of specialized community-based care (SCBC) interventions and health care delivery models, using the lens of patient-centredness?

Research Methods

Literature Search

Search Strategy

A literature search was performed on May 3, 2012, using Ovid MEDLINE and EBSCO Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and on May 4, 2012, using Thomson Reuters Web of Knowledge, Social Sciences Citation Index, for studies published from January 1, 2002, until May 31, 2012. We developed a qualitative mega-filter by combining existing published qualitative filters. (7-10) The filters were compared, and redundant search terms were deleted. We added exclusionary terms to the search filter that were likely to identify quantitative research and would reduce the number of false-positive results. We then applied the qualitative mega-filter to 9 condition-specific search filters (atrial fibrillation, diabetes, chronic conditions, COPD, chronic wounds, coronary artery disease, CHF, multiple morbidities, and stroke). Appendix 1 provides details of the search strategy. Titles and abstracts were reviewed by 2 reviewers and, for those studies meeting the eligibility criteria, full-text articles were obtained.

This search identified all the qualitative research on the chronic diseases listed above. Databases were hand searched to identify studies that were related to patient-centredness, according to the research-based definition. Titles and abstracts were reviewed, and those that related to the core principles of patient-centredness were included. The following terms and concepts were used to identify publications associated with patient-centredness or patient-centeredness: patient-focused; people-/person-/client-/consumer-/family-centred, biopsychosocial model; health advocacy/promotion, health literacy; patient empowerment, patient autonomy, shared decision-making; and collaborative care, among others.

Finally, the studies on chronic diseases and patient-centredness were hand searched to identify those that were relevant to SCBC. Eligible interventions included components of SCBC identified by the 2012 HQO report (1) (Table 1) and interventions described as SCBC or using related terminology (e.g., shared care, interdisciplinary primary care, chronic disease management).

Table 1: Frequently Reported Components of Specialized Community-Based Care.

| Components | Description |

|---|---|

| Disease-specific education | Education about the signs, symptoms, and etiology of a chronic condition |

| Medication education/review | Education about the side effects of medication, the relationship of medication to chronic disease management, and the importance of medication adherence |

| Medication titration | Assistance with appropriate dosing of specific medications |

| Diet counselling | Counselling on disease-specific diets |

| Physical activity counselling | Counselling on physical activity |

| Lifestyle counselling | Counselling on lifestyle choices, such as smoking cessation and alcohol intake |

| Self-care support behaviour | Encouragement for patients to monitor weight, symptoms, and medications |

| Self-care tools | Patient diaries for recording weight, diet, or symptoms |

| Evidence-based guidelines | Clinical practice guidelines based on evidence |

| Regular follow-up | Regular follow-up visits between the beginning and end of the treatment phase |

Source: Health Quality Ontario.(1)

Inclusion Criteria

English-language full reports

published between January 1, 2002, and May 31, 2012;

primary qualitative empirical research (using any descriptive or interpretive qualitative methodology, including the qualitative component of mixed-methods studies) and secondary syntheses of primary qualitative empirical research;

participating patients engaged in an SCBC program or a program with components related to the definitions of SCBC;

research with an approach consistent with the core principles of patient-centred care.

Exclusion Criteria

studies addressing topics other than the experience of a patient or provider engaging in an SCBC program or a program with related components;

studies labelled “qualitative” that did not use a qualitative descriptive or interpretive methodology (e.g., case studies, experiments, or observational analyses using qualitative categorical variables);

quantitative research (i.e., using statistical hypothesis testing, using primarily quantitative data or analyses, or expressing results in quantitative or statistical terms);

studies that did not pose an empirical research objective or question, or involve primary or secondary analysis of empirical data.

Qualitative Analysis

We analyzed published qualitative research using techniques of integrative qualitative meta-synthesis (9, 11-13). Qualitative meta-synthesis, also known as qualitative research integration, is an integrative technique that summarizes research over several studies with the intent of combining findings from multiple papers. Qualitative meta-synthesis has 2 objectives: first, summarizing the aggregate of a result should reflect the range of findings that exist while retaining the original meaning of the authors; second, through a process of comparing and contrasting findings across studies, a new integrative interpretation of the phenomenon should be produced. (14)

Predefined topic and research questions guided research collection, data extraction, and analysis. Topics were defined in stages, as available relevant literature was identified and the corresponding evidence-based analyses proceeded. All qualitative research relevant to the conditions under analysis was retrieved. In consultation with HQO, a theoretical sensitivity to patient centeredness and vulnerability was used to further refine the dataset. Finally, specific topics were chosen and a final search was performed to retrieve papers relevant to these questions. This analysis included papers that addressed experiences of patients with chronic conditions and their providers in the context of receiving SCBC interventions.

Data extraction focused on, and was limited to, findings relevant to this research topic. Qualitative findings are the “data-driven and integrated discoveries, judgments, or pronouncements researchers offer about the phenomena, events, or cases under investigation.” (9) In addition to the researchers’ findings, original data excerpts (participant quotes, stories, or incidents) embedded in the findings were also extracted to help illustrate specific findings and, when useful, to facilitate communication of meta-synthesis findings.

Through a staged coding process similar to that of grounded theory, (15-16) studies’ findings were broken into their component parts (key themes, categories, concepts) and then gathered across studies to regroup and relate to each other thematically. This process allowed for organization and reflection on the full range of interpretative insights across the body of research. (9, 17) These categorical groupings provided the foundation from which interpretations of the social and personal phenomena relevant to patients’ experience were synthesized. A “constant comparative” and iterative approach was used, in which preliminary categories were repeatedly compared with research findings, raw data excerpts, and co-investigators’ interpretations of the same studies, as well as to the original Ontario Health Technology Assessment Committee (OHTAC)-defined topic, emerging evidence-based analyses of clinical evaluations of related technologies, (1) and feedback from OHTAC deliberations and expert panels on issues emerging in relation to the topic.

Quality of Evidence

For valid epistemologic reasons, the field of qualitative research lacks consensus on the importance of, and methods and standards for, critical appraisal. (18) Qualitative health researchers conventionally underreport procedural details, (12) and the quality of findings tends to rest more on the conceptual prowess of the researchers than on methodologic processes. (18) Theoretically sophisticated findings are promoted as a marker of study quality for making valuable theoretical contributions to social science academic disciplines. (19) However, theoretical sophistication is not necessary for contributing potentially valuable information to a synthesis of multiple studies, or to inform questions posed by the interdisciplinary and interprofessional field of health technology assessment. Qualitative meta-synthesis researchers typically do not exclude qualitative research on the basis of independently appraised quality. This approach is common to multiple types of interpretive qualitative synthesis. (9-10, 14, 18-22)

For this review, the academic peer review and publication process was used to eliminate scientifically unsound studies according to current standards. Beyond this, all topically relevant, accessible studies using any qualitative, interpretive, or descriptive methodology were included. The value of the research findings was appraised solely in terms of their relevance to our research questions and of data that supported the authors’ findings.

Results of Evidence-Based Analysis

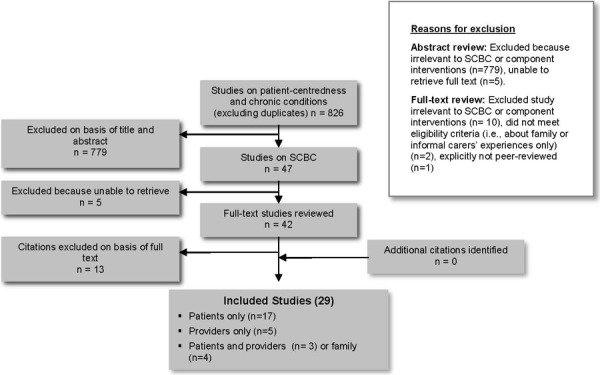

The database search yielded 826 citations published between January 1, 2002, and May 2012 (with duplicates removed). Articles were excluded on the basis of information in the title and abstract. Two reviewers reviewed all titles and abstracts to refine the database to qualitative research relevant to any of the chronic diseases. Figure 1 shows the breakdown of when and for what reason citations were excluded from the analysis.

Figure 1: Citation Flow Chart.

Twenty-nine studies met the inclusion criteria. The reference lists of the included studies were hand searched to identify any additional potentially relevant studies, but no additional citations were included.

Description of Studies

The included studies were diverse in their research focus and questions. Of the studies that directly related to SCBC interventions and patient-centredness, 7 examined patients’ or providers’ perceptions of care delivered at nurse-led, shared care clinics. (23-29) Many of these clinics were disease specific—for example, CHF clinics, (26) COPD clinics, (23, 30) and diabetes clinics. (24-25, 27-28, 31) Most clinics were based at primary care centres, but some, such as a patient rehabilitation centre, (32), a leg ulcer clinic, (33) and a CHF clinic, (34) were based at secondary care facilities.

Some studies asked patients and providers to compare their experience of a new model of care with the care they had previously received in a community setting. (24-25, 28, 33, 35-37) These included comparing new models of shared care to the care they previously received (patients), or to care delivered in either primary or secondary health care settings (providers). (24-25, 28) In 2 instances, studies considered the patient in moving from specialty care to primary care clinics. (36-37)

Two studies examined patients’ and providers’ experiences of telehome care interventions, but because these interventions were diverse in the type of technology used and degree of patient involvement in the care, generalizations about telehome care from those studies was avoided. (38-39) Two studies examined patients’ experiences of a physical activity intervention. (32, 40)

The remaining studies were indirectly related to SCBC and patient-centredness. These studies tended to have broader research questions that examined patients’ and providers’ perceptions of chronic conditions, and it was through these findings that the studies described specific components of SCBC (e.g., diet or lifestyle counselling). (41-44) In a similar vein, several studies specifically examined patients’ perceptions of the health information they received during care. These were included in our analysis because those patients reported on SCBC-type interventions. (45-47)

Three core themes emerged from the qualitative research on the management of chronic conditions through SCBC:

patients’ health beliefs affect their participation in SCBC interventions;

patients’ experiences with community-based care differ from their experiences with hospital-based care;

patients and providers value the role of nurses differently in community-based chronic disease care.

Patients’ Health Beliefs Affect Their Participation

Recruitment into SCBC programs—or the therapies associated with some interventions (e.g., activity-based rehabilitation)—suggested that patients do not know as much about their chronic diseases as providers presume. For patients whose reports indicated a more comprehensive knowledge of their condition, manifestations of their condition appeared to affect their perceptions of competence in social functioning; this, in turn, influenced their willingness to participate in or access SCBC interventions. Patients reported that social support provided as part of SCBC interventions was helpful in improving their understanding of their condition or ameliorating the psychosocial barriers to accessing those services.

Patients’ Knowledge of Their Conditions

Some patients reported that limits to their understanding of their diagnosis were made apparent by the SCBC interventions they were expected to undergo, whether they were activity-based rehabilitation (48) or a strict medication regimen. (45) Some patients reported that they learned more about their condition and the factors that led to it from SCBC-based providers than they did from the diagnosing clinicians, because the SCBC-based providers spent time discussing their condition in a way that was personalized to their current life experience. (26, 32) Some patients reported that poor knowledge about their condition was because they were given limited information when they received their diagnosis (32, 45) or because they were reluctant to seek further information at the time of diagnosis. (43, 45)

Communication Between Providers and Patients

Other patients—particularly those with communication impairments acquired as a result of their condition (e.g., aphasia)—reported feeling psychologically isolated by their speech difficulties and felt particularly reliant on the format of the SCBC program, because it affected their perception of how able or competent they were to participate. (35, 43, 46, 49) Patients also reported perceptions of condition-based physical and psychosocial limitations with several conditions, (e.g., CHF, COPD, and stroke) noting that these limitations affected their willingness to participate in SCBC interventions because of the physical and psychosocial demands of the interventions or opportunities to access them. (27, 32, 34, 42-43, 47, 50) However, patients were not unanimous about which interventions were positive or negative in these respects. Although social support via contacts outside the patients’ homes was highly valued by many, (32, 34, 41, 43, 50) others said they valued having providers come to their home for individualized care. (38, 43) A common theme across both groups was the value participants placed on acquisition of self-care management skills, regardless of where the care was provided.

Information and Self-Management

Diet, physical activity, and lifestyle counselling could be viewed with suspicion if they are not in a format patients can understand, (35, 49) given at a time patients can process information, (41, 46-47) or explained and situated in a way that is relevant to patients’ personal situation and disease. (23, 26, 35, 47) In lieu of written information, some patients preferred personalized verbal exchange. (35) Conflicting health information from various providers or the media (e.g., which foods one should eat) generated skepticism among patients about the value of such information. (25, 45, 47)

Patients’ Experiences With Community-Based Care Versus Hospital-Based Care

The studies focused on the perceptions and experiences of patients with chronic diseases as they related to participation in SCBC interventions. Although SCBC interventions are not based in hospitals, patients with chronic diseases frequently have experience with hospital-based care, either because they receive their diagnosis there or because they visit the hospital during acute episodes of their disease. Study authors quoted patients who compared their experiences in hospital to their experiences with SCBC interventions.

Negative Dimensions of Hospital Care

Many patients reported associating the severity of their illness with the setting of their care; for example, they reported interpreting their transfer of care to a hospital inpatient program or a hospital-based specialist as an indication that their disease had progressed. (36-37, 51) Both patients (33, 37, 48) and providers (23) characterized hospital care as focused on disease state and not individualized to unique patients. Some patients reported that hospital-based care made them feel like a “number” (33) or a “case,” (36-37) or a nuisance to care providers. (48) Some patients reported that the feature of home care that most positively contrasted with hospital care was lack of privacy during hospital stays. (40) However, some patients also reported feeling alone and lacking support when discharged from hospital to home, reflecting diminished access to care providers. (35)

Value of Relationships With Providers

Patients who preferred community-based care indicated that they appreciated the repeated and longer access to knowledgeable providers, in contrast to hospital-based care. (24, 26-27, 30, 43, 49) Patients reported that SCBC gave them access to longer appointments with providers, particularly nursing staff, enabling them to build a rapport with their providers and form responsive relationships that might not have been possible in a hospital. (24, 27, 35, 43) Trust in their care providers led patients to feel that they could tell their stories and have them heard. (24, 35, 43) This helped some patients feel that they could take a more active role in their own care (i.e., self-management), contributing to treatment planning that reflected their specific care needs or life goals. (27, 30, 33, 38, 49, 52)

Specialized Community-Based Care and Socialization

Patients participating in programs that got them out of their homes and into the community (e.g., peer support groups, exercise and rehabilitation programs, regular specialty clinic visits), or that brought providers into their homes, reported that the resulting social support reduced their sense of isolation and increased their confidence. (32-34, 40-41) Some patients—particularly those in neighbourhoods characterized as socioeconomically deprived—reported the important role of community networks in informing patients about new SCBC services. (48) Patients who attended rehabilitation for their chronic diseases often commented that the presence of other patients and providers was crucial to their motivation. (32) Such socialization opportunities were sometimes valued even when patients did not believe that the program itself improved their underlying physical condition. (40)

Patients and Providers Value the Role of Nurses Differently

Several studies had findings specific to patients’ and providers’ perceptions of the role of nurses in nurse-led shared care and disease-specific clinics, located either in primary care settings or in interdisciplinary primary care practices. (23-26, 28, 30-31, 33, 37, 49, 51, 53-54) Of these 13 studies, 7 included patients’ perspectives, (24, 26-28, 37, 49, 54) 5 included nurses’ perspectives, (23, 26, 30, 49, 53) and 2 captured general practitioners’ perspectives. (25, 51) These studies all point to the perceived value of the role of nurses in supporting patients’ self-management, in personalizing patient care, and in referring patients to specialists when needed.

Nurses’ Support of Patients’ Self-Management

One dimension of the nurses’ role that was highlighted by study findings central to SCBC interventions for chronic diseases was their support for patients’ self-management. (23, 26-27, 30-31, 49) Patients saw nurses as key supports for self-management, (26, 31) and nurses themselves reported supporting patients’ self-management as an integral part of their role. (26-27) Self-management support included teaching the communication and social skills required for self-management (27) and promoting patients’ feelings of autonomy. (31) More generally, patients reported that nurses provided basic social support (27) and information on specific chronic diseases and activities to prevent complications. (26)

However, not all nurses’ approaches to supporting self-management were reported as equal by patients. Several studies found that nurses lacked skills or failed to facilitate self-management. (23, 29, 53) This included the failure to tend to the patient as an individual (23) and to incorporate patients’ perspectives into self-management counselling. (29) In such instances, the result was a one-size-fits-all approach to self-management that focused on provision of generalized medical information. (23, 29, 53) Findings from 2 studies supported the use of mentors and senior nursing staff to help nurses adopt an individualized and holistic approach to counselling. (29, 53)

Nurses’ Rapport With Patients and Personalized Approach to Care

According to the ethos of patient-centred care, an important enabler of personalized approaches to care is the rapport developed between patient and provider. Many nurses reported seeing their role as one of building rapport, naming this as a key step in better understanding their patients’ disease and providing guidance and health information tailored to their patients’ condition and life experiences. (26-27, 30, 49) Key elements of building rapport reported by both patients and nurses were sustained and focused time with patients (30) and repeated visits with the same provider. (27, 37) Physicians reported awareness that time constraints limited how long they could spend with each patient, making it difficult for them to establish the same degree of rapport with their patients as nurses did. (25, 51) Patients similarly reported that physicians were more difficult to access and spend time with than nursing staff. (28, 54) Some nurses reported awareness of this and described an element of their role as improving communication between patients and their general practitioners. (25, 49)

Another important aspect of nurses’ therapeutic role was providing referrals to other health care providers as needed or requested. (24, 31, 37, 49, 53) Nurses’ ability to do this appropriately was facilitated by the rapport they established with their patients as a result of knowing the patient’s needs and social context. (31, 49, 53)

Patient-Perceived Limits to Nurses’ Expertise

While some patients reported perceiving nurses as having greater expertise than they were allowed to exercise under the supervision of a physician (for example, changing medication prescriptions), (28) others were aware of the limits to nurses’ expertise. (24, 31, 33, 37) Patients reported expecting nurses to make referrals to other practitioners when the limits of the nurse’s knowledge or scope of practice were reached. (24, 28, 31, 33, 37) In this way, patients reported that nurses’ referral role contributed to their sense of security (31) and confidence in nursing care. (37) Some patients reported taking comfort in the perception that the nurse’s practice was overseen by a physician; this suggested to them that the physician was still involved in their care. (24) However, nurses in 1 study of a shared-care diabetes clinic reported struggling to have their expertise recognized by physicians in the clinic, and pointed to the local and health system barriers that made fully shared care in those contexts difficult. (25)

Limitations

Qualitative studies are designed to contribute new insights into poorly understood social phenomena. Findings are not intended to generalize directly to populations, although meta-synthesis across several qualitative studies does build an increasingly robust understanding that is more likely to be transferable.

The diversity of interventions that fall under SCBC (i.e., the multiple components listed in Table 1) mean that findings might not be generalizable to all forms of SCBC or its components. The qualitative studies reviewed here addressed (in either their research question or findings) most interventions that comprise SCBC (i.e., disease-specific education, medication education and review, medication titration, diet counselling, physical activity counselling, lifestyle counselling, and self-care support). However, given the broad focus of many of the studies, there were no specific results about each type of intervention (e.g., diet counselling versus self-care support). Other aspects of SCBC, such as self-care tools, evidence-based guidelines, and regular follow-up, were not covered as discrete topics of investigation in the evidence reviewed. Had we expanded our focus to include patients’ experiences with chronic conditions without specific interventional foci, we might have captured more evidence on specific interventions. However, such an approach would have generated a volume of research for review that would have exceeded the resources available. Consequently, the focus on SCBC was deemed appropriate for this evidence-based review.

The studies that were selected focused on the perceptions and experiences of patients with chronic diseases as these relate to their participation in SCBC-type interventions and the experiences of providers employed in those interventions. However, with respect to patients’ experiences, many of the studies captured this broadly, not just as it applied to the program in question. Some of these experiences (e.g., physician care contrasted with nursing care) were not formally incorporated into the conclusions, nor were they the explicit focus of this review, but when patient experiences spoke to and illuminated features of SCBC interventions that were relevant to this review, they were included in the results.

Not all patients shared the same experiences of SCBC or had the same expectations of patient-centred care. This review sensitized information for planning and evaluating patient-centred SCBC, but findings should be placed into context of the setting and services.

Conclusions

This synthesis of 29 primary qualitative studies on the experiences of patients with chronic conditions and their providers in SCBC programs and using the analytical lens of patient-centred care revealed 3 themes:

patients’ health beliefs affect their participation in SCBC interventions;

patients’ experiences with community-based care differ from their experiences with hospital-based care;

patients and providers value the role of nurses differently in community-based chronic disease care.

Patients with chronic diseases who participated in SCBC interventions reported greater satisfaction when SCBC helped them better understand their diagnosis, facilitated increased socialization, provided them with a role in managing their own care, and assisted them in overcoming psychological and social barriers.

Acknowledgements

Editorial Staff

Pierre Lachaine

Jeanne McKane, CPE, ELS(D)

Elizabeth Jean Betsch, ELS

Medical Information Services

Kaitryn Campbell, BA(H), BEd, MLIS

Kellee Kaulback, BA(H), MISt

Expert Panel for Health Quality Ontario: Optimizing Chronic Disease Management in the Community (Outpatient) Setting.

| Name | Title | Organization |

|---|---|---|

| Shirlee Sharkey (chair) | President & CEO | Saint Elizabeth Health Care |

| Theresa Agnew | Executive Director | Nurse Practitioners’ Association of Ontario |

| Onil Bhattacharrya | Clinician Scientist | Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto |

| Arlene Bierman | Ontario Women’s Health Council Chair in Women’s Health | Department of Medicine, Keenan Research Centre in the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto |

| Susan Bronskill | Scientist | Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences |

| Catherine Demers | Associate Professor | Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, McMaster University |

| Alba Dicenso | Professor | School of Nursing, McMaster University |

| Mita Giacomini | Professor | Centre of Health Economics & Policy Analysis, Department of Clinical Epidemiology & Biostatistics |

| Ron Goeree | Director | Programs for Assessment of Technology in Health Research Institute, St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton |

| Nick Kates | Senior Medical Advisor | Health Quality Ontario – QI McMaster University Hamilton Family Health Team |

| Murray Krahn | Director | Toronto Health Economics and Technology Assessment Collaborative, University of Toronto |

| Wendy Levinson | Sir John and Lady Eaton Professor and Chair | Department of Medicine, University of Toronto |

| Raymond Pong | Senior Research Fellow and Professor | Centre for Rural and Northern Health Research and Northern Ontario School of Medicine, Laurentian University |

| Michael Schull | Deputy CEO & Senior Scientist | Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences |

| Moira Stewart | Director | Centre for Studies in Family Medicine, University of Western Ontario |

| Walter Wodchis | Associate Professor | Institute of Health Management Policy and Evaluation, University of Toronto |

Appendices

Appendix 1: Literature Search Strategies

Mega Filter: Ovid MEDLINE

Interviews+

(theme$ or thematic).mp.

qualitative.af.

Nursing Methodology Research/

questionnaire$.mp.

ethnological research.mp.

ethnograph$.mp.

ethnonursing.af.

phenomenol$.af.

(grounded adj (theor$ or study or studies or research or analys?s)).af.

(life stor$ or women* stor$).mp.

(emic or etic or hermeneutic$ or heuristic$ or semiotic$).af. or (data adj 1 saturat$).tw. or participant observ$.tw.

(social construct$ or (postmodern$ or post- structural$) or (post structural$ or poststructural$) or post modern$ or post-modern$ or feminis$ or interpret$).mp.

(action research or cooperative inquir$ or co operative inquir$ or co- operative inquir$).mp.

(humanistic or existential or experiential or paradigm$).mp.

(field adj (study or studies or research)).tw.

human science.tw.

biographical method.tw.

theoretical sampl$.af.

((purpos$ adj4 sampl$) or (focus adj group$)).af.

(account or accounts or unstructured or open-ended or open ended or text$ or narrative$).mp.

(life world or life-world or conversation analys?s or personal experience$ or theoretical saturation).mp

(lived or life adj experience$.mp

cluster sampl$.mp.

observational method$.af.

content analysis.af.

(constant adj (comparative or comparison)).af.

((discourse$ or discurs$) adj3 analys?s).tw.

narrative analys?s.af.

heidegger$.tw.

colaizzi$.tw.

spiegelberg$.tw.

(van adj manen$).tw.

(van adj kaam$).tw.

(merleau adj ponty$).tw

.husserl$.tw

foucault$.tw.

(corbin$ adj2 strauss$).tw

-

glaser$.tw.

NOT

p =.ti,ab.

p<.ti,ab.

p>.ti,ab.

p =.ti,ab.

p<.ti,ab.

p>.ti,ab.

p-value.ti,ab.

retrospective.ti,ab.

regression.ti,ab.

statistical.ti,ab.

Mega Filter: EBSCO Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)

Interviews+

MH audiorecording

MH Grounded theory

MH Qualitative Studies

MH Research, Nursing

MH Questionnaires+

MH Focus Groups (12639)

MH Discourse Analysis (1176)

MH Content Analysis (11245)

MH Ethnographic Research (2958)

MH Ethnological Research (1901)

MH Ethnonursing Research (123)

MH Constant Comparative Method (3633)

MH Qualitative Validity+ (850)

MH Purposive Sample (10730)

MH Observational Methods+ (10164)

MH Field Studies (1151)

MH theoretical sample (861)

MH Phenomenology (1561)

MH Phenomenological Research (5751)

MH Life Experiences+ (8637)

MH Cluster Sample+ (1418)

Ethnonursing (179)

ethnograph* (4630)

phenomenol* (8164)

grounded N1 theor* (6532)

grounded N1 study (601)

grounded N1 studies (22)

grounded N1 research (117)

grounded N1 analys?s (131)

life stor* (349)

women’s stor* (90)

emic or etic or hermeneutic$ or heuristic$ or semiotic$ (2305)

data N1 saturat* (96)

participant observ* (3417)

social construct* or postmodern* or post-structural* or post structural* or poststructural* or post modern* or post-modern* or feminis* or interpret* (25187)

action research or cooperative inquir* or co operative inquir* or co-operative inquir* (2381)

humanistic or existential or experiential or paradigm* (11017)

field N1 stud* (1269)

field N1 research (306)

human science (132)

biographical method (4)

theoretical sampl* (983)

purpos* N4 sampl* (11299)

focus N1 group* (13775)

account or accounts or unstructured or open-ended or open ended or text* or narrative* (37137)

life world or life-world or conversation analys?s or personal experience* or theoretical saturation (2042)

lived experience* (2170)

life experience* (6236)

cluster sampl* (1411)

theme* or thematic (25504)

observational method* (6607)

questionnaire* (126686)

content analysis (12252)

discourse* N3 analys?s (1341)

discurs* N3 analys?s (35)

constant N1 comparative (3904)

constant N1 comparison (366)

narrative analys?s (312)

Heidegger* (387)

Colaizzi* (387)

Spiegelberg* (0)

van N1 manen* (261)

van N1 kaam* (34)

merleau N1 ponty* (78)

husserl* (106)

Foucault* (253)

Corbin* N2 strauss* (50)

strauss* N2 corbin* (88)

-

glaser* (302)

NOT

TI statistical OR AB statistical

TI regression OR AB regression

TI retrospective OR AB retrospective

TI p-value OR AB p-value

TI p< OR AB p<

TI p< OR AB p<

TI p= OR AB p=

Mega Filter: Thomson Reuters Web of Knowledge, Social Science Citation Index

TS=interview*

TS=(theme*)

TS=(thematic analysis)

TS=qualitative

TS=nursing research methodology

TS=questionnaire

TS=(ethnograph*)

TS= (ethnonursing)

TS=(ethnological research)

TS=(phenomenol*)

TS=(grounded theor*) OR TS=(grounded stud*) OR TS=(grounded research) OR TS=(grounded analys?s)

TS=(life stor*) OR TS=(women’s stor*)

TS=(emic) OR TS=(etic) OR TS=(hermeneutic) OR TS=(heuristic) OR TS=(semiotic) OR TS=(data saturat*) OR TS=(participant observ*)

TS=(social construct*) OR TS=(postmodern*) OR TS=(post structural*) OR TS=(feminis*) OR TS=(interpret*)

TS=(action research) OR TS=(co-operative inquir*)

TS=(humanistic) OR TS=(existential) OR TS=(experiential) OR TS=(paradigm*)

TS=(field stud*) OR TS=(field research)

TS=(human science)

TS=(biographical method*)

TS=(theoretical sampl*)

TS=(purposive sampl*)

TS=(open-ended account*) OR TS=(unstructured account) OR TS=(narrative*) OR TS=(text*)

TS=(life world) OR TS=(conversation analys?s) OR TS=(theoretical saturation)

TS=(lived experience*) OR TS=(life experience*)

TS=(cluster sampl*)

TS=observational method*

TS=(content analysis)

TS=(constant comparative)

TS=(discourse analys?s) or TS =(discurs* analys?s)

TS=(narrative analys?s)

TS=(heidegger*)

TS=(colaizzi*)

TS=(spiegelberg*)

TS=(van manen*)

TS=(van kaam*)

TS=(merleau ponty*)

TS=(husserl*)

TS=(foucault*)

TS=(corbin*)

TS=(strauss*)

-

TS=(glaser*)

NOT

TS=(p-value)

TS=(retrospective)

TS=(regression)

TS=(statistical)

Suggested Citation

This report should be cited as follows: Winsor S, Smith A, Vanstone M, Giacomini M, Brundisini FK, DeJean D. Experiences of patient-centredness with specialized community-based care: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser [Internet]. 2013 September;13(17):1-33. Available from: http://www.hqontario.ca/en/documents/eds/2013/full-report-OCDM-patient-centredness.pdf.

Indexing

The Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series is currently indexed in MEDLINE/PubMed, Excerpta Medica/EMBASE, and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination database.

Permission Requests

All inquiries regarding permission to reproduce any content in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series should be directed to: EvidenceInfo@hqontario.ca.

How to Obtain Issues in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series

All reports in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series are freely available in PDF format at the following URL: http://www.hqontario.ca/en/mas/mas_ohtas_mn.html.

Conflict of Interest Statement

All reports in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series are impartial. There are no competing interests or conflicts of interest to declare.

Peer Review

All reports in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series are subject to external expert peer review. Additionally, Health Quality Ontario (HQO) posts draft reports and recommendations on its website for public comment before publication. For more information, please visit: http://www.hqontario.ca/en/mas/ohtac_public_engage_overview.html.

About Health Quality Ontario

Health Quality Ontario is an arms-length agency of the Ontario government. It is a partner and leader in transforming Ontario’s health care system so that it can deliver a better experience of care, better outcomes for Ontarians, and better value for money.

Health Quality Ontario strives to promote health care that is supported by the best available scientific evidence. Health Quality Ontario works with clinical experts, scientific collaborators and field evaluation partners to develop and publish research that evaluates the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of health technologies and services in Ontario.

Based on the research conducted by HQO and its partners, the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee (OHTAC) — a standing advisory sub-committee of the HQO Board — makes recommendations about the uptake, diffusion, distribution, or removal of health interventions to Ontario’s Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, clinicians, health system leaders, and policy-makers.

This research is published as part of Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series, which is indexed in EBSCO Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, EMBASE, MEDLINE, and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Corresponding OHTAC recommendations and other associated reports are also published on the HQO website. Visit http://www.hqontario.ca for more information.

About the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series

To conduct its comprehensive analyses, HQO and/or its research partners reviews the available scientific literature, making every effort to consider all relevant national and international research; collaborates with partners across relevant government branches; consults with clinical and other external experts and developers of new health technologies; and solicits any necessary supplemental information.

In addition, HQO collects and analyzes information about how a health intervention fits within current practice and existing treatment alternatives. Details about the diffusion of the intervention into current health care practices in Ontario add an important dimension to the review. Information concerning the health benefits; economic and human resources; and ethical, regulatory, social, and legal issues relating to the intervention assist in making timely and relevant decisions to optimize patient outcomes.

The public consultation process is available to individuals and organizations wishing to comment on reports and recommendations before publication. For more information, please visit: http://www.hqontario.ca/en/mas/ohtac_public_engage_overview.html.

Disclaimer

This report was prepared by HQO or one of its research partners for the OHTAC and developed from analysis, interpretation, and comparison of scientific research. It also incorporates, when available, Ontario data and information provided by experts and applicants to HQO. It is possible that relevant scientific findings could have been reported since completion of the review. This report is current to the date of the literature review specified in the methods section, if available. This analysis may be superseded by an updated publication on the same topic. Please check the HQO website for a list of all publications: http://www.hqontario.ca/en/mas/mas_ohtas_mn.html.

Health Quality Ontario

130 Bloor Street West, 10th Floor

Toronto, Ontario

M5S 1N5

Tel: 416-323-6868

Toll Free: 1-866-623-6868

Fax: 416-323-9261

Email: EvidenceInfo@hqontario.ca

ISSN 1915-7398 (online)

ISBN 978-1-4606-1249-1 (PDF)

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2013

List of Tables

| Table 1: Frequently Reported Components of Specialized Community-Based Care |

List of Figures

| Figure 1: Citation Flow Chart |

List of Abbreviations

- CHF

Congestive heart failure

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- HQO

Health Quality Ontario

- OHTAC

Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee

- SCBC

Specialized community-based care

References

- 1.Health Quality Ontario. Specialized community-based care: an evidence based analysis. Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series. 2012 Nov;12(20):1–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mead N, Bower P. Patient centeredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:1087–110. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan P. Shared decision-making—the pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NRCPicker.com [Internet] Boston: National Rearch Corporation-Picker Institute; c. 2001. Eight Dimensions of Patient-Centered Care [one screen] [[updated 2013; cited 2012 Aug 12]]. Available from: http://www.nrcpicker.com/member-services/eight-dimensions-of-pcc/

- 5.Guastello S, Lepore M. White Paper: Improving PCC across the continuum of care [Internet]. Derby, CT: Planetree Organization; 2012 August 2012. [[cited 2012 Aug 15]]; Available from: http://planetree.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Advancing-PCC-Across-the-Continuum_Planetree-White-Paper_August-2012.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Advancing the practice of patient- and family-centred care in primary care and other ambulatory settings: How to get started. [Internet] Bethesda, MD: Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. 2008. [[cited 2012 July 26]]. Available from: http://www.ipfcc.org/pdf/GettingStarted-AmbulatoryCare.pdf .

- 7.Anello C, Fleiss JL. Exploratory or analytic meta-analysis: should we distinguish between them? J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48(1):109–16. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banning J. Design and Implementation Assessment Device (DIAD) Version 0.3: A response from a qualitative perspective [Internet]. [[cited 2012 August 14]];School of Education, Colorado State University; Available from: http://mycahs.colostate.edu/James.H.Banning/PDFs/Design%20and%20Implementation%20Assessment%20Device.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbour R, Barbour M. Evaluating and synthesizing qualitative research: the need to develop a distinctive approach. J Eval Clin Pract. 2003;9(2):179–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2003.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Toward a metasynthesis of qualitative findings on motherhood in HIV-positive women. Res Nurs Health. 2003;26(2):153–70. doi: 10.1002/nur.10072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Creating metasummaries of qualitative findings. Nurs Res. 2003;52(4):226–33. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York: Springer Publishing Co. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thorne S, Jenson L, Kearney M, Noblit G, Sandelowski M. Qualitative metasynthesis: reflections on methodological orientation and ideological agenda. Qual Health Res. 2004;14:1342–65. doi: 10.1177/1049732304269888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saini M, Shlonsky A. Systematic synthesis of qualitative research. New York: Oxford University Press. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage Publications. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage Publications. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finfgeld DL. Metasynthesis: The state of the art—so far. Qual Health Res. 2003;13(7):893–904. doi: 10.1177/1049732303253462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melia KM. Recognizing quality in qualitative research. In: Bourgeault I, DeVries R, Dingwall R, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. Los Angeles: Sage Publications. 2010:559–74. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Finding the findings in qualitative studies. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2002;34(3):213–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finfgeld-Connett D. Meta-synthesis of presence in nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2006;55(6):708–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paterson B. Coming out as ill: understanding self-disclosure in chronic illness from a meta-synthesis of qualitative research. In: Webb C, Roe, B, editors. Reviewing research evidence for nursing practice: Systematic reviews. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. 2007:73–83. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noblit G, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park: Sage Publications. 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eva OE, Birgitta K, Kjell L, Anna E. Communication and self-management education at nurse-led COPD clinics in primary health care. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(2):209–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eijkelberg I, Mur-Veeman IM, Spreeuwenberg C, Koppers RLW. Patient focus groups about nurse-led shared care for the chronically ill. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;47(4):329–36. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eijkelberg IM, Spreeuwenberg C, Wolffenbuttel BH, van Wilderen LJ, Mur-Veeman IM. Nurse-led shared care diabetes projects: lessons from the nurses’ viewpoint. Health Policy. 2003;66(1):11–27. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(03)00041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lloyd-Williams F, Beaton S, Goldstein P, Mair F, May C, Capewell S. Patients’ and nurses’ views of nurse-led heart failure clinics in general practice: a qualitative study. Chronic Illn. 2005;1(1):39–47. doi: 10.1177/17423953050010010201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moser A, van der Bruggen H, Widdershoven G, Spreeuwenberg C. Self-management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a qualitative investigation from the perspective of participants in a nurse-led, shared-care programme in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health. 2008;(8):91. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith SM, O’Leary M, Bury G, Shannon W, Tynan A, Staines A, et al. A qualitative investigation of the views and health beliefs of patients with Type 2 diabetes following the introduction of a diabetes shared care service. Diabet Med. 2003;20(10):853–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heo S, Moser DK, Lennie TA, Okoli C. Health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure: ask the patients. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006;21(2):108. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson A, Courtney-Pratt H, Lea E, Cameron-Tucker H, Turner P, Cummings E, et al. Transforming clinical practice amongst community nurses: mentoring for COPD patient self-management. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(11C):370–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moser A, van der Bruggen H, Widdershoven G. Competency in shaping one’s life: Autonomy of people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a nurse-led, shared-care setting; a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43(4):417–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andreassen S, Wyller TB. Patients’ experiences with self-referral to in-patient rehabilitation: a qualitative interview study. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27(21):1307–13. doi: 10.1080/09638280500163711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogden L, Honey S. Patients’ experiences of attending a new community leg ulcer clinic. J Community Nurs. 2005;19(3):34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tierney S, Elwers H, Sange C, Mamas M, Rutter MK, Gibson M, et al. What influences physical activity in people with heart failure?: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(10):1234–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lilley SA, Lincoln NB, Francis VM. A qualitative study of stroke patients’ and carers’ perceptions of the stroke family support organizer service. Clin Rehabil. 2003;17(5):540–7. doi: 10.1191/0269215503cr647oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawton J, Peel E, Parry O, Araoz G, Douglas M. Lay perceptions of type 2 diabetes in Scotland: bringing health services back in. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(7):1423–35. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDowell JRS, McPhail K, Halyburton G, Brown M, Lindsay G. Perceptions of a service redesign by adults living with type 2 diabetes. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(7):1432–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mair FS, Hiscock J, Beaton SC. Understanding factors that inhibit or promote the utilization of telecare in chronic lung disease. Chronic Illn. 2008;4(2):110–7. doi: 10.1177/1742395308092482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lamothe L, Fortin J-P, Labbe F, Gagnon M-P, Messikh D. Impacts of telehomecare on patients, providers, and organizations. Telemed J E Health. 2006;12(3):363–9. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2006.12.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Graham R, Kremer J, Wheeler G. Physical exercise and psychological well-being among people with chronic illness and disability—a grounded approach. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(4):447–58. doi: 10.1177/1359105308088515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kitzmuller G, Asplund K, Haggstrom T. The long-term experience of family life after stroke. J Neurosci Nurs. 2012;44(1):E1–E13. doi: 10.1097/JNN.0b013e31823ae4a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rayman K, Ellison G. Home alone: the experience of women with type 2 diabetes who are new to intensive control. Health Care Women Int. 2004;25(10):900–15. doi: 10.1080/07399330490508604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hare R, Rogers H, Lester H, McManus R, Mant J. What do stroke patients and their carers want from community services? Fam Pract. 2006;23(1):131–6. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clark AM. “It’s like an explosion in your life...”: lay perspectives on stress and myocardial infarction. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12(4):544–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chambers JA, O’Carroll RE, Hamilton B, Whittaker J, Johnston M, Sudlow C, et al. Adherence to medication in stroke survivors: a qualitative comparison of low and high adherers. Br J Health Psychol. 2011;16(3):592–609. doi: 10.1348/2044-8287.002000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rose TA, Worrall LE, Hickson LM, Hoffmann TC. Aphasia friendly written health information: content and design characteristics. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2011;13(4):335–47. doi: 10.3109/17549507.2011.560396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lawrence M, Kerr S, Watson H, Paton G, Ellis G. An exploration of lifestyle beliefs and lifestyle behaviour following stroke: findings from a focus group study of patients and family members. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:97. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harkins C, Shaw R, Gillies M, Sloan H, MacIntyre K, Scoular A, et al. Overcoming barriers to engaging socio-economically disadvantaged populations in CHD primary prevention: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:391. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rankin SH, Butzlaff A, Carroll DL. Reedy I. FAMISHED for support: recovering elders after cardiac events. Clin Nurse Spec. 2005;19(3):142–9. doi: 10.1097/00002800-200505000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clarke P, Black SE. Quality of life following stroke: negotiating disability, identity, and resources. J Appl Gerontol. 2005;24(4):319–36. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brez S, Rowan M, Malcolm J, Izzi S, Maranger J, Liddy C, et al. Transition from specialist to primary diabetes care: a qualitative study of perspectives of primary care physicians. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-10-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Joyce KE, Smith KE, Henderson G, Greig G, Bambra C. Patient perspectives of Condition Management Programmes as a route to better health, well-being and employability. Fam Pract. 2010;27(1):101–9. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmp083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lundh L, Rosenhall L, Tornkvist L. Care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary health care. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56(3):237–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jonsdottir H. Research-as-if-practice—a study of family nursing partnership with couples experiencing severe breathing difficulties. J Fam Nurs. 2007;13(4):443–60. doi: 10.1177/1074840707309210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]