Abstract

Background

Rurality can contribute to the vulnerability of people with chronic diseases. Qualitative research can identify a wide range of health care access issues faced by patients living in a remote or rural setting.

Objective

To systematically review and synthesize qualitative research on the advantages and disadvantages rural patients with chronic diseases face when accessing both rural and distant care.

Data Sources

This report synthesizes 12 primary qualitative studies on the topic of access to health care for rural patients with chronic disease. Included studies were published between 2002 and 2012 and followed adult patients in North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand.

Review Methods

Qualitative meta-synthesis was used to integrate findings across primary research studies.

Results

Three major themes were identified: geography, availability of health care professionals, and rural culture. First, geographic distance from services poses access barriers, worsened by transportation problems or weather conditions. Community supports and rurally located services can help overcome these challenges. Second, the limited availability of health care professionals (coupled with low education or lack of peer support) increases the feeling of vulnerability. When care is available locally, patients appreciate long-term relationships with individual clinicians and care personalized by familiarity with the patient as a person. Finally, patients may feel culturally marginalized in the urban health care context, especially if health literacy is low. A culture of self-reliance and community belonging in rural areas may incline patients to do without distant care and may mitigate feelings of vulnerability.

Limitations

Qualitative research findings are not intended to generalize directly to populations, although meta-synthesis across a number of qualitative studies builds an increasingly robust understanding that is more likely to be transferable. Selected studies focused on the vulnerability experiences of rural dwellers with chronic disease; findings emphasize the patient rather than the provider perspective.

Conclusions

This study corroborates previous knowledge and concerns about access issues in rural and remote areas, such as geographical distance and shortage of health care professionals and services. Unhealthy behaviours and reduced willingness to seek care increase patients’ vulnerability. Patients’ perspectives also highlight rural culture’s potential to either exacerbate or mitigate access issues.

Plain Language Summary

People who live in a rural area may feel more vulnerable—that is, more easily harmed by their health problems or experiences with the health care system. Qualitative research looks at these experiences from the patient’s point of view. We found 3 broad concerns in the studies we looked at. The first was geography: needing to travel long distances for health care can make care hard to reach, especially if transportation is difficult or the weather is bad. The second concern was availability of health professionals: rural areas often lack health care services. Patients may also feel powerless in “referral games” between rural and urban providers. People with low education or without others to help them may find navigating care more difficult. When rural services are available, patients like seeing clinicians who have known them for a long time, and like how familiar clinicians treat them as a whole person. The third concern was rural culture: patients may feel like outsiders in city hospitals or clinics. As well, in rural communities, people may share a feeling of self-reliance and community belonging. This may make them more eager to take care of themselves and each other, and less willing to seek distant care. Each of these factors can increase or decrease patient vulnerability, depending on how health services are provided.

Background

In July 2011, the Evidence Development and Standards (EDS) branch of Health Quality Ontario (HQO) began developing an evidentiary framework for avoidable hospitalizations. The focus was on adults with at least 1 of the following high-burden chronic conditions: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), coronary artery disease (CAD), atrial fibrillation, heart failure, stroke, diabetes, and chronic wounds. This project emerged from a request by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care for an evidentiary platform on strategies to reduce avoidable hospitalizations.

After an initial review of research on chronic disease management and hospitalization rates, consultation with experts, and presentation to the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee (OHTAC), the review was refocused on optimizing chronic disease management in the outpatient (community) setting to reflect the reality that much of chronic disease management occurs in the community. Inadequate or ineffective care in the outpatient setting is an important factor in adverse outcomes (including hospitalizations) for these populations. While this did not substantially alter the scope or topics for the review, it did focus the reviews on outpatient care. HQO identified the following topics for analysis: discharge planning, in-home care, continuity of care, advanced access scheduling, screening for depression/anxiety, self-management support interventions, specialized nursing practice, and electronic tools for health information exchange. Evidence-based analyses were prepared for each of these topics. In addition, this synthesis incorporates previous EDS work, including Aging in the Community (2008) and a review of recent (within the previous 5 years) EDS health technology assessments, to identify technologies that can improve chronic disease management.

HQO partnered with the Programs for Assessment of Technology in Health (PATH) Research Institute and the Toronto Health Economics and Technology Assessment (THETA) Collaborative to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the selected interventions in Ontario populations with at least 1 of the identified chronic conditions. The economic models used administrative data to identify disease cohorts, incorporate the effect of each intervention, and estimate costs and savings where costing data were available and estimates of effect were significant. For more information on the economic analysis, please contact either Murray Krahn at murray.krahn@theta.utoronto.ca or Ron Goeree at goereer@mcmaster.ca.

HQO also partnered with the Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis (CHEPA) to conduct a series of reviews of the qualitative literature on “patient centredness” and “vulnerability” as these concepts relate to the included chronic conditions and interventions under review. For more information on the qualitative reviews, please contact Mita Giacomini at giacomin@mcmaster.ca.

The Optimizing Chronic Disease Management in the Outpatient (Community) Setting mega-analysis series is made up of the following reports, which can be publicly accessed at http://www.hqontario.ca/evidence/publications-and-ohtac-recommendations/ohtas-reports-and-ohtac-recommendations.

Optimizing Chronic Disease Management in the Outpatient (Community) Setting: An Evidentiary Framework

Discharge Planning in Chronic Conditions: An Evidence-Based Analysis

In-Home Care for Optimizing Chronic Disease Management in the Community: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Continuity of Care: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Advanced (Open) Access Scheduling for Patients With Chronic Diseases: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Screening and Management of Depression for Adults With Chronic Diseases: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Self-Management Support Interventions for Persons With Chronic Diseases: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Specialized Nursing Practice for Chronic Disease Management in the Primary Care Setting: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Electronic Tools for Health Information Exchange: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Health Technologies for the Improvement of Chronic Disease Management: A Review of the Medical Advisory Secretariat Evidence-Based Analyses Between 2006 and 2011

Optimizing Chronic Disease Management Mega-Analysis: Economic Evaluation

How Diet Modification Challenges Are Magnified in Vulnerable or Marginalized People With Diabetes and Heart Disease: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis

Chronic Disease Patients’ Experiences With Accessing Health Care in Rural and Remote Areas: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis

Patient Experiences of Depression and Anxiety With Chronic Disease: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis

Experiences of Patient-Centredness With Specialized Community-Based Care: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis

Objective of Analysis

To systematically review and synthesize qualitative research on the advantages and disadvantages rural patients with chronic diseases face when accessing both rural and distant care.

Clinical Need and Target Population

This systematic review addresses health care access issues faced by patients living in a remote or rural setting. Rurality can be considered a type of vulnerability, a concept that was first identified and defined in a review of relevant conceptual literature. Rurality increases patients’ potential susceptibility to health risks. It may also contribute to a sense of defenselessness or marginalization when patients experience difficulties accessing either local or remote health care services.

The target population of this review was adults (> 18 years of age) with specific chronic conditions (congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, wounds, and chronic disease/multimorbidities) who live in rural and remote areas. Definitions of rural and remote vary and may relate to population density, population size, or distance from an urban area or an essential service. (1) For this analysis, we use the Statistics Canada and Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development definition of rural: small towns and villages with fewer than 1,000 inhabitants and a population density that ranges from 150 to 400 individuals per square kilometre. (1)

Vulnerability

A narrative synthesis of seminal conceptual published and grey literature on vulnerability was conducted to inform the articulation of study objectives and the literature retrieval process. In general, vulnerability is defined as a characteristic of groups that may be wounded or harmed. (2-4) Vulnerability is the result of the total interaction between the person and the external environment. (3, 4) In particular, vulnerable groups have an increased relative risk of, or susceptibility to, adverse health outcomes. (3) Evidence of higher vulnerability or risk includes higher morbidity, premature mortality, and diminished quality of life. Low social and economic status and lack of external and environmental resources may contribute to disease susceptibility and are therefore indicators of vulnerability. Vulnerability is largely situational, with individuals typically becoming more vulnerable during life transitions and major life changes.

Importantly, the concept of vulnerability is linked to the idea of risk and defenselessness due to exposure to contingencies, stress, and difficulty coping with them. (4, 5) Vulnerability requires both an external element of risk, shock, and stress to which an individual is exposed (crises), and an internal element of defenselessness, or a lack of means to cope without damaging loss. (4, 5) Vulnerability further depends on the probability of exposure over time. (3) It has several dimensions: susceptibility to exposure, capacity for coping with a crisis, potential serious consequences of exposure to a crisis, (5, 6) and uncertainty about the foreseeability of crises. (7) Terms and concepts often related to vulnerability include helplessness, defenselessness, dependency, fragility, insecurity, centrality, absence of effective regulation, low resiliency, susceptibility to health problems, harm or neglect, marginalized, and different. The opposite of vulnerability is resiliency, the positive capacity to absorb and recover from crisis events. (8)

Groups often characterized as vulnerable include the poor; people subjected to discrimination, intolerance, subordination, or stigma; and people who are politically marginalized, disenfranchised, or denied human rights. (9) Vulnerable groups may include women and children, visible minorities, immigrants, lesbians and gay men, the homeless, and the elderly. (9) Health conditions themselves can also render people vulnerable, especially conditions such as terminal illness or mental illness, or psychological, cognitive, functional, or communication impairments. (8, 10) Vulnerability can arise from factors that contribute to socioeconomic status, such as age, sex, race, ethnicity, social capital (e.g., family or marital status, social networks), and human capital (e.g., education, employment, income, and housing). (3, 8, 11)

Geographic location also contributes to vulnerability. (12) Rurality in particular may affect the health of patients by increasing the level of risk due to isolation and lack of access to health care services. Therefore, rurality increases the level of susceptibility to risk, as well as the sense of defenselessness and marginalization, affecting patients’ well-being and willingness to seek care when ill. It is common knowledge, for example, that rural communities lack access to secondary and tertiary health services, so rural individuals may be more vulnerable to complications from complex or chronic health problems. However, we lack a comprehensive understanding of rural groups’ experiences of vulnerability and resiliency in relation to access to health care for chronic conditions. This review helps fill these knowledge gaps with empirically grounded evidence of rural dwellers’ experiences.

Ontario Context

Ontario (and Canada as a whole) faces great challenges in providing health care services to remote and rural populations. About 15% of Ontario’s population lives in remote and rural areas, and such populations tend to be exposed to higher health risks because of where they live. (1) It is important to address access issues for populations who live in remote and rural areas of the province.

Evidence-Based Analysis

Research Questions

What advantages and disadvantages do rural patients experience when accessing both rural and distant health care?

Research Methods

Literature Search

Search Strategy

A literature search was performed on May 3, 2012, using Ovid MEDLINE and EBSCO Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and on May 4, 2012, using ISI Web of Science Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), for studies published from January 1, 2002, until May 2, 2012. We developed a qualitative mega-filter by combining existing published qualitative filters. (13-15) The filters were compared, and redundant search terms were deleted. We added exclusionary terms to the search filter to identify quantitative research and reduce the number of false positives. We then applied the qualitative mega-filter to 9 condition-specific search filters (atrial fibrillation, diabetes, chronic conditions, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], chronic wounds, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, multiple morbidities, and stroke). Appendix 1 provides details of the search strategy. Titles and abstracts were reviewed by 2 reviewers and, for those studies meeting the eligibility criteria, full-text articles were obtained.

Inclusion Criteria

English language full-reports

published between January 1, 2002, and May 2, 2012

primary qualitative empirical research (using any descriptive or interpretive qualitative methodology, including the qualitative component of mixed-methods studies) and secondary syntheses of primary qualitative empirical research

adult patients (> 18 years of age)

Canada, United States, Europe, New Zealand, and Australia

published research work (no theses)

studies that addressed “vulnerability”

rural context-specific

Exclusion Criteria

studies addressing topics other than the lived experience of rural patients

studies labelled “qualitative” but that did not use a qualitative descriptive or interpretive methodology (e.g., case studies, experiments, or observational analyses using qualitative categorical variables)

quantitative research (i.e., using statistical hypothesis testing, using primarily quantitative data or analyses, or expressing results in quantitative or statistical terms)

studies that did not pose an empirical research objective or question, or involve primary or secondary analysis of empirical data

Qualitative Analysis

We analyzed published qualitative research using techniques of integrative qualitative meta-synthesis. (16-19) Qualitative meta-synthesis, also known as qualitative research integration, is an integrative technique that summarizes research over a number of studies with the intent of combining findings from multiple papers. Qualitative meta-synthesis has 2 objectives: first, summarizing the aggregate of a result should reflect the range of findings that exist while retaining the original meaning of the authors; second, through a process of comparing and contrasting findings across studies, a new integrative interpretation of the phenomenon should be produced. (20)

Predefined topic and research questions guided research collection, data extraction, and analysis. Topics were defined in stages, as available relevant literature was identified and the corresponding evidence-based analyses proceeded. All qualitative research relevant to the conditions under analysis was retrieved. In consultation with Health Quality Ontario, a theoretical sensitivity to patient centredness and vulnerability was used to further refine the dataset. Finally, specific topics were chosen and a final search was performed to retrieve papers relevant to these questions. This analysis focused on the conditions of vulnerability that stem from living in rural and remote areas, addressing the advantages and disadvantages rural dwellers face when accessing local and remote health care services.

Data extraction focused on, and was limited to, findings relevant to this research topic. Qualitative findings are the “data-driven and integrated discoveries, judgments, and/or pronouncements researchers offer about the phenomena, events, or cases under investigation.” (17) In addition to the researchers’ findings, original data excerpts (participant quotes, stories, or incidents) embedded in the findings were also extracted to help illustrate specific findings and, when useful, to facilitate communication of meta-synthesis findings.

Through a staged coding process similar to that of grounded theory, (21, 22) studies’ findings were broken into their component parts (key themes, categories, concepts) and then gathered across studies to regroup and relate to each other thematically. This process allowed for organization and reflection on the full range of interpretative insights across the body of research. (17, 23) These categorical groupings provided the foundation from which interpretations of the social and personal phenomena relevant to rural vulnerability were synthesized. A “constant comparative” and iterative approach was used, in which preliminary categories were repeatedly compared to research findings, raw data excerpts, and co-investigators’ interpretations of the same studies, as well as to the original Ontario Health Technology Assessment Committee (OHTAC)-defined topic, emerging evidence-based analyses of clinical evaluations of related technologies, and feedback from OHTAC deliberations and expert panels on issues emerging in relation to the topic.

Quality of Evidence

For valid epistemological reasons, the field of qualitative research lacks consensus on the importance of, and methods/standards for, critical appraisal. (24) Qualitative health researchers conventionally under-report procedural details, (18) and the quality of findings tends to rest more on the conceptual prowess of the researchers than on methodological processes. (24) Theoretically sophisticated findings are promoted as a marker of study quality for making valuable theoretical contributions to social science academic disciplines. (25) However, theoretical sophistication is not necessary for contributing potentially valuable information to a synthesis of multiple studies, or to inform questions posed by the interdisciplinary and interprofessional field of health technology assessment. Qualitative meta-synthesis researchers typically do not exclude qualitative research on the basis of independently appraised quality. This approach is common to multiple types of interpretive qualitative synthesis. (16, 17, 20, 25-29)

For this review, the academic peer review and publication process was used to eliminate scientifically unsound studies according to current standards. Beyond this, all topically relevant, accessible research studies using any qualitative, interpretive, or descriptive methodology were included. The value of the research findings was appraised solely in terms of their relevance to our research questions and the presence of data that supported the authors’ findings.

Results of Evidence-Based Analysis

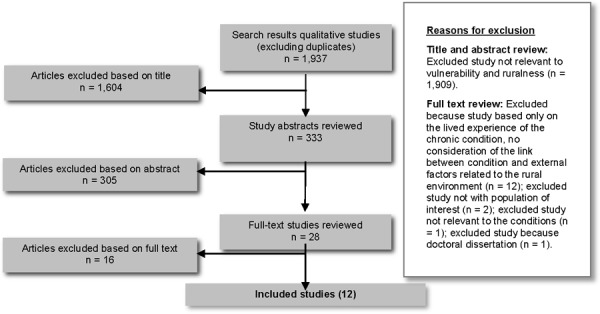

The database search yielded 1,937 studies published between January 1, 2002, and May 2, 2012 (with duplicates removed). Articles were excluded based on information in the title and abstract. Two reviewers reviewed all titles and abstracts to refine the database to qualitative research relevant to any of the chronic diseases. Figure 1 shows the breakdown of the steps and reasons for excluding studies from the analysis.

Figure 1: Study Flow Chart.

Twelve studies met the inclusion criteria. The reference lists of the included studies were hand searched to identify any additional potentially relevant studies, but no additional citations were included.

For each included study, the study design, jurisdiction, condition, and rural subgroup were identified and are summarized below (Tables 1 to 4).

Table 1: Body of Evidence by Study Design.

| Study Design | Number |

|---|---|

| Unspecified qualitative methodology | 7 |

| Ethnographic study | 3 |

| Grounded theory study | 1 |

| Qualitative multicase study | 1 |

| Total | 12 |

Table 4: Body of Evidence by Rural Subgroup.

| Rural Subgroup | Number |

|---|---|

| Rural Aboriginal people | 3 |

| Rural African American people | 1 |

| Rural women | 2 |

| Rural African American women | 1 |

| Unspecified rural population | 5 |

| Total | 12 |

Table 2: Body of Evidence by Jurisdiction.

| Jurisdiction | Number |

|---|---|

| Canada (not Ontario) | 4 |

| Ontario | 2 |

| United States | 5 |

| United Kingdom | 1 |

| Total | 12 |

Table 3: Body of Evidence by Condition.

| Condition | Number |

|---|---|

| Diabetes | 7 |

| Heart (myocardial infarction and coronary artery disease) | 4 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 |

| Total | 12 |

Themes

Consistent with the conceptual literature, the included studies characterized vulnerability as a broad interaction between the individual and the environment, and likewise emphasized the relationship between external risk and internal defenselessness and incapacity to face harm. (3-5)

The major themes that emerged from this analysis focused on 3 different aspects of health care access in the rural environment: geography, the availability of health care professionals, and rural culture. Issues concerning geography and availability of health care providers resonated with common knowledge about access issues in rural settings. The third theme is perhaps less commonly recognized, but evidence indicated that culture can either mitigate or exacerbate access challenges in rural and remote locations. This report highlights not only rural groups’ access challenges and problems but also some advantages of rural health care systems from the perspective of persons with chronic diseases. In the following discussion, key sub-themes are indicated in italics.

Geography

Geography characterizes access issues in remote and rural settings. Access to health care for chronic diseases is affected by distance, isolation, weather, and transportation. These factors impede access to distant services and favour access to local services.

Rural patients commonly understood distance as the geographic space between their place of residence and points of access to the health care system—in particular, access to the local hospital and to the nearest tertiary system. (30-34)

Some patients reported experiencing isolation as a result of distance, which in turn intensified the perception of distance as a major structural barrier to access. Both distance and isolation contributed to stress for rural chronic disease patients, their families, and caregivers. (30-34) Local conditions of the rural environment also contributed to stress, as rural areas presented logistical challenges to moving freely and receiving immediate care. (31, 35)

Weather affected both access and willingness to seek care in rural areas. (35) People feared that if they experienced transportation difficulties, they would not receive the help they needed. Their vulnerability grew in the face of travel under adverse conditions. Even where rural health care services (such as primary care) were available, logistical challenges of local travel made it difficult to seek care. (30)

Transportation presented another major barrier to access to health care services in rural areas. (30-32, 34) Individuals with chronic diseases lacked access to or knowledge about the transportation system and means for reaching health services. (35) Patients considered transportation to referral appointments to be their personal responsibility; arranging transportation was often described as a cause of stress, exacerbated by poor weather conditions and the acuity of the health issue. (34) For example, patients may not be sure how long it will take to drive to urban care, whether they risk an emergency during the drive, or when an ambulance or patient transport is more appropriate or available. (35) Distance-related challenges often meant that “driving a vehicle was critically important to accessing health care,” (30) as public transportation is often underdeveloped in rural areas and using taxis for long distances may not be affordable. (31, 32, 34) Patients without vehicles had to “depend on the good will of family and friends when they needed to access health care,” (30) meaning time off from work for the driver as well as the patient. (35) Sometimes, appointments were not scheduled in a way that considered the significant travel time involved for rural patients and required them to make multiple trips or arrange overnight accommodation to make an early-morning appointment. (35) Transportation also came with associated costs (gas, overnight stays, parking), and this was a burden to many patients. (31, 32, 35)

Although distance, isolation, weather, and transportation presented obvious challenges, qualitative research also found that these factors had some positive impacts on patients’ social environment. Personal relationships among rural dwellers developed to mitigate the stressful effects of distance, isolation, weather, and transportation problems. (30, 33, 34) A strong experience of place, conceptualized as a web of relationships, made challenges more tolerable. (30, 33, 35, 36)

Availability of Health Care Providers

Availability of health care providers clearly influenced access to health care, treatment, and rehabilitation for chronic conditions in the rural context. This issue pervaded the rural health care literature on access. (30, 31, 34, 36-40) Three particular issues affected experiences of health providers’ access, availability, and responsiveness: the rural-urban referral system; health care professional shortages in rural areas; and the lack of educational opportunities and peer support programs in the rural context. At the same time, persons with chronic diseases valued experience and some higher-quality dimensions as a part of rural care—particularly the patient-centredness that emerged from long-term relationships and providers’ familiarity with the patient’s context, history, and community.

Rural dwellers with chronic diseases faced many barriers to access specialized and tertiary health care services, (30, 33, 34) beginning at the point of referral. Patients relied on their primary care providers to be gatekeepers to urban services. A study in southwestern Ontario (34) examined “referral games” and their impact on women following a myocardial infarction. Rural providers’ relationships and interactions with urban providers affected successful referral and access to specialized care. The perception of a “game” implied “that there [are] rules, players, and the possibility of winning or losing with regard to accessing a particular service. For the most part, the women were silent players in the referral game.” (35) Patients may feel helpless and defenseless in negotiations between rural and urban providers, and relatively disadvantaged because of their location: “For all participants, living in a rural community meant one had to accept the fact that some services would not be available nearby, and the women and their families were not keen to challenge that reality.” (35) Rural dwellers may see urban providers as “urban-centric,” and both rural providers and patients sometimes feared that advocating or complaining would prejudice urban providers against them. (35) Some patients felt that urban providers misunderstood their rural living circumstances, or that urban providers judged patients, their family, and even their rural providers negatively (e.g., as “country bumpkins”). (35) For rural patients who also belonged to a minority cultural group, an additional layer of misunderstanding and mistrust was reported. (38, 39) Following hospitalization or specialized care, health care information and follow-up plans may not be communicated clearly back to the rural setting. Some providers saw prolonged hospitalization as a way to give rural patients access to follow-up care that would have been too difficult to arrange after a more timely discharge. (34)

All of the studies noted local health care professional shortages as a crucial barrier to access. (30-41) Rural care was characterized by a high turnover of primary care clinicians and prevalent lack of physician specialists. Primary care providers took on a larger role in rural health care, as many patients “rarely ventured to urban centres for appointments with [specialists] and depended almost exclusively on the local family physicians.” (30) Local primary care physicians were highly valued by rural patients with chronic conditions, especially when they remained in the community long enough to get to know the patients. (30) High professional turnover was reported as distressing, and indicative that the physician was not “loyal” to the community. (31) Long-term relationships and the opportunity to get to know patients better may also have alleviated concerns expressed by some Aboriginal patients that it was difficult to communicate with health care professionals. (38) Some patients suggested that this difficulty could be alleviated if health care professionals made the effort to relate to them in a more personal manner. (38) Rural dwellers reported a chronic need not only for more primary care physicians, but also for other professionals including nutritionists, dietitians, health educators, and pharmacists. (32, 33) When community members left to gain health professional education, they found upon their return that they could not practice the way they were taught in urban centres. (36)

Many rural dwellers with chronic conditions turned to alternative therapies for treatment or self-management. For example, an African American group of people with diabetes reported strategies including teas, dietary products, nutritional supplements, and herbs. (33) An Aboriginal group of people with diabetes reported commonplace use of traditional medicines to complement biomedical treatment. (38) Other studies reported very limited mentions of home or folk remedies. In Arcury’s (37) study of rural white patients with diabetes in the southern United States, only 1 of 39 participants mentioned using an herbal remedy.

Rural dwellers with chronic conditions realized the importance of educational opportunities and peer support programs to improve the management of their condition. (30-33, 36-40) They perceived in particular that physicians lacked time to “teach you all the things you need to know,” (33) and valued simply “being able to talk” to knowledgeable others (either lay or professional) about their condition. (30) Health literacy may be low among rural dwellers with chronic diseases. (33) However, health education programs and community support groups were underprovided in rural and remote areas. (30, 32, 33, 40) Culturally appropriate education programs were highly valued; for instance, Aboriginal participants emphasized the “need for traditional ceremonies to be part of diabetes education programs” (38) and the need for programs that accommodate traditional understandings of illness and medicine. (39)

Despite the provider shortages endemic to rural health services, the qualitative research also identified some quality advantages to rural health care, particularly, the personalization of care. (30, 32, 34-37, 41) The few clinicians serving rural communities tended to be very familiar with their patients and their families, histories, and circumstances. This put clinicians in a better position to provide patient-centred care: they are better able to tailor care to the patient and work with other health care professionals such as pharmacists. (30-32, 34, 35, 38) Rural dwellers with chronic diseases highly valued this feature of their local care. They also tended to expect and experience the opposite (e.g., “to be treated as a number”) when they ventured to urban settings for health services. (30, 35) The degree of integration of a health service or program into the rural community affected people’s willingness to seek care, as well as their adherence to treatment. Participants expected service integration with the community to impact effectiveness of care, complication rates, and health outcomes. (30, 34-36, 38, 41)

Rural Culture

Most studies emphasized the influence of rural culture on health care experiences and the importance of understanding how rural culture affected the success of health care services in rural and remote areas. Rural culture can both impede and facilitate access to care. Cultural marginalization of rural dwellers in the urban health context, low health literacy, and reticence to seek care posed barriers to care for rural dwellers with chronic conditions. On the other hand, rural traditions of self-reliance and community belonging facilitated access to care.

Cultural differences between rural and urban communities can lead to cultural marginalization of rural patients in urban settings. (30, 34-36, 38-41) In urban care contexts, rural dwellers with chronic diseases felt stigmatized and marginalized, increasing their experiences of vulnerability and decreasing their willingness to seek care outside the rural setting. (35) “Women described feeling like ‘outsiders’ during some of their interactions and experiences in tertiary settings. Sometimes this occurred in response to an interaction with a health professional who made what were perceived as negative comments about rural life or who gave information that had little or no relevance to their rural context.” (34) This experience may be especially acute for those who are also members of a minority cultural or ethnic group. (38, 39, 41)

Low health literacy (an inability to access and understand information important for maintaining and improving one’s health) has been found to be common among rural dwellers with chronic diseases, highlighting the need for relevant and culturally meaningful health education. (31, 32, 36-40) The knowledge necessary for self-management of chronic diseases can be complex, and patients may face many novel problems that they must solve on their own. (33) Low health literacy can foster false beliefs and unhealthy behaviours, making rural dwellers more vulnerable to adverse health outcomes. (32, 33, 36, 37, 39, 40) Literacy, like other dimensions of vulnerability, is not only an attribute of the person but also of his/her environment—specifically, the sources, terms, format, and languages conveying available information. For example, in Baffin Island, instructions and labels in English (rather than Inuktitut) were unintelligible to many. (39) Some found that rural providers were too busy to tell them all they needed to know. (33) Other sources consulted for guidance on self-care included case managers, pharmacists, local support groups, the Internet, and family and friends. (31-35)

Many studies found that rural dwellers with chronic diseases expressed a surprising tolerance for barriers to health care due to their rurality, and they expressed a reticence to seek care. (31, 34, 35) “The ‘persona’ associated with rural living left many rural-living men and women waiting until ‘they could no longer function’ to seek physician’s help.” (31) The ability to engage in work was described as both the threshold for seeking care and a main barrier to doing so. For participants who worked as farmers, time away from the farm was a large burden. (31) Other rural patients reported having low expectations of health care and trying not to rely too heavily on health services. (30, 34) Many expressed a preference for self-reliance and self-sufficiency to fill care gaps caused by living in a rural setting. (30, 34-35) For this reason, patients may not consider their rural area to be underserviced, and they may understand the challenges health professionals typically face in rural practice. (30-36, 38, 40, 41) Many rural dwellers with chronic diseases reported feeling gratitude for the health care providers and services that were available. (30, 35) This feeling may extend to a reported reluctance to burden the health care system, as a kind of civic responsibility, and not feeling entitled to extensive care, as described by Caldwell in her study of women with heart disease. (34) Rural culture can carry an obligation to “make do” with available resources and solve one’s problems independently: for example, creating one’s own exercise program “to meet what they understood to be the rehabilitation requirements when a referral was not possible.” (35)

Although self-reliance may inhibit care seeking, it was also a highly valued source of strength and personal control for rural dwellers with chronic conditions and helped mitigate the experience of inadequate access to services. (30-32, 34, 35, 37, 40) It helped individuals feel a sense of control and diminished vulnerability, and it fostered active self-management of chronic conditions. (33, 35) Self-management of conditions such as diabetes can be daily hard work, and patients reported a sense of “taking charge” of their condition and situation. (33)

A sense of community belonging in rural culture can diminish the experience of vulnerability related to living in a rural area, as well as the experience of vulnerability in urban settings, but it can also leave rural patients more vulnerable to stigma. Rural patients reported feeling “relationally” closer to their neighbours: “Many described how neighbours ‘know’ and ‘look out for’ each other. The neighbors seemed to readily come to the aid of the participants when illness struck.” (31) Community relationships were described as a source of support and information. (34) The community belonging of health providers also enhanced the trust and rapport necessary for good therapeutic relationships. (39) However, a close-knit community also made it difficult for individuals to admit their health-related dependencies to others, which may have contributed to stigma for certain diseases, such as diabetes in a rural African American community (33) or in a Baffin Island community. (39) Nonbiomedical, culturally based beliefs about etiology (e.g., diabetes as transmitted by transfusion or sexual activity) can further contribute to stigma. (39) Some rural dwellers were consequently reluctant to talk about their conditions or seek help in an obvious way. (33) As part of integrating services into rural communities, health information may need to be reconciled and conveyed within frameworks coherent with local culture and belief systems. (39)

Limitations

Qualitative research provides theoretical and contextual insights into the experiences of limited numbers of people in specific settings. While qualitative insights are robust and often enlightening for understanding experiences and planning services in other settings, the findings of the studies reviewed here—and of this synthesis—do not strictly generalize to the Ontario (or any specific) population. Findings were limited to the conditions included in the body of literature synthesized (i.e., coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, diabetes, COPD). Other conditions were included in the search strategy, but no relevant literature was found relating to the rural experience of patients living with these conditions (atrial fibrillation, chronic conditions [not further specified], chronic wounds, congestive heart failure, multiple morbidities, and stroke). This report may not capture experiences of other common chronic conditions (e.g., mental health conditions, addictions, osteoarthritis, dementia).

Conclusions

By focusing on patients’ experience of vulnerability, this study corroborates previous knowledge and concerns related to health care access in rural and remote areas (such as distance, transportation, weather conditions, shortage of health care professionals, and limited availability of health care services), highlighting how unhealthy behaviours and reduced willingness to seek care can increase patients’ susceptibility to external risks and vulnerability. Patients’ perspectives also highlighted the potential of rural culture to both exacerbate and mitigate access issues. Rural culture can nourish feelings of marginalization from the health care system and foster reticence to seek care. However, community belonging, personalization of relationships with health care professionals, and self-reliance may be useful means of coping with deficiencies and gaps in the rural health care system.

Glossary

- Rural and remote areas

Small towns and villages with fewer than 1,000 inhabitants and a population density that ranges from 150 to 400 individuals per square kilometre. (1)

- Vulnerability

A concept linked to the idea of risk and defenselessness due to the exposure to contingencies and stress, and difficulty coping with them. Therefore, there are 2 sides of vulnerability: an external side, which is the risks, shocks, and stress to which an individual is exposed, and an internal side, which is defenselessness related to a lack of means of coping without damaging loss.

- Vulnerable populations

Social groups with an increased relative risk of or susceptibility to adverse health outcomes. This differential vulnerability or risk is evidenced by increased comparative morbidity, premature mortality, and diminished quality of life.

Acknowledgements

Editorial Staff

Pierre Lachaine

Jeanne McKane, CPE, ELS(D)

Amy Zierler, BA

Medical Information Services

Kaitryn Campbell, BA(H), BEd, MLIS

Kellee Kaulback, BA(H), MISt

Expert Panel for Health Quality Ontario: Optimizing Chronic Disease Management in the Community (Outpatient) Setting.

| Name | Title | Organization |

|---|---|---|

| Shirlee Sharkey (chair) | President & CEO | Saint Elizabeth Health Care |

| Theresa Agnew | Executive Director | Nurse Practitioners’ Association of Ontario |

| Onil Bhattacharrya | Clinician Scientist | Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto |

| Arlene Bierman | Ontario Women’s Health Council Chair in Women’s Health | Department of Medicine, Keenan Research Centre in the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto |

| Susan Bronskill | Scientist | Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences |

| Catherine Demers | Associate Professor | Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, McMaster University |

| Alba Dicenso | Professor | School of Nursing, McMaster University |

| Mita Giacomini | Professor | Centre of Health Economics & Policy Analysis, Department of Clinical Epidemiology & Biostatistics |

| Ron Goeree | Director | Programs for Assessment of Technology in Health (PATH) Research Institute, St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton |

| Nick Kates | Senior Medical Advisor | Health Quality Ontario - QI McMaster University Hamilton Family Health Team |

| Murray Krahn | Director | Toronto Health Economics and Technology Assessment (THETA) Collaborative, University of Toronto |

| Wendy Levinson | Sir John and Lady Eaton Professor and Chair | Department of Medicine, University of Toronto |

| Raymond Pong | Senior Research Fellow and Professor | Centre for Rural and Northern Health Research and Northern Ontario School of Medicine, Laurentian University |

| Michael Schull | Deputy CEO & Senior Scientist | Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences |

| Moira Stewart | Director | Centre for Studies in Family Medicine, University of Western Ontario |

| Walter Wodchis | Associate Professor | Institute of Health Management Policy and Evaluation, University of Toronto |

Appendices

Appendix 1: Literature Search Strategies

Mega Filter: Ovid MEDLINE

Interviews+

(theme$ or thematic).mp.

qualitative.af.

Nursing Methodology Research/

questionnaire$.mp.

ethnological research.mp.

ethnograph$.mp.

ethnonursing.af.

phenomenol$.af.

(grounded adj (theor$ or study or studies or research or analys?s)).af.

(life stor$ or women* stor$).mp.

(emic or etic or hermeneutic$ or heuristic$ or semiotic$).af. or (data adj 1 saturat$).tw. or participant observ$.tw.

(social construct$ or (postmodern$ or post- structural$) or (post structural$ or poststructural$) or post modern$ or post-modern$ or feminis$ or interpret$).mp.

(action research or cooperative inquir$ or co operative inquir$ or co- operative inquir$).mp.

(humanistic or existential or experiential or paradigm$).mp.

(field adj (study or studies or research)).tw.

human science.tw.

biographical method.tw.

theoretical sampl$.af.

((purpos$ adj4 sampl$) or (focus adj group$)).af.

(account or accounts or unstructured or open-ended or open ended or text$ or narrative$).mp.

(life world or life-world or conversation analys?s or personal experience$ or theoretical saturation).mp

(lived or life adj experience$.mp

cluster sampl$.mp.

observational method$.af.

content analysis.af.

(constant adj (comparative or comparison)).af.

((discourse$ or discurs$) adj3 analys?s).tw.

narrative analys?s.af.

heidegger$.tw.

colaizzi$.tw.

spiegelberg$.tw.

(van adj manen$).tw.

(van adj kaam$).tw.

(merleau adj ponty$).tw

.husserl$.tw

foucault$.tw.

(corbin$ adj2 strauss$).tw

-

glaser$.tw.

NOT

p =.ti,ab.

p<.ti,ab.

p>.ti,ab.

p =.ti,ab.

p<.ti,ab.

p>.ti,ab.

p-value.ti,ab.

retrospective.ti,ab.

regression.ti,ab.

statistical.ti,ab.

Mega Filter: EBSCO Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)

Interviews+

MH audiorecording

MH Grounded theory

MH Qualitative Studies

MH Research, Nursing

MH Questionnaires+

MH Focus Groups (12639)

MH Discourse Analysis (1176)

MH Content Analysis (11245)

MH Ethnographic Research (2958)

MH Ethnological Research (1901)

MH Ethnonursing Research (123)

MH Constant Comparative Method (3633)

MH Qualitative Validity+ (850)

MH Purposive Sample (10730)

MH Observational Methods+ (10164)

MH Field Studies (1151)

MH theoretical sample (861)

MH Phenomenology (1561)

MH Phenomenological Research (5751)

MH Life Experiences+ (8637)

MH Cluster Sample+ (1418)

Ethnonursing (179)

ethnograph* (4630)

phenomenol* (8164)

grounded N1 theor* (6532)

grounded N1 study (601)

grounded N1 studies (22)

grounded N1 research (117)

grounded N1 analys?s (131)

life stor* (349)

women’s stor* (90)

emic or etic or hermeneutic$ or heuristic$ or semiotic$ (2305)

data N1 saturat* (96)

participant observ* (3417)

social construct* or postmodern* or post-structural* or post structural* or poststructural* or post modern* or post-modern* or feminis* or interpret* (25187)

action research or cooperative inquir* or co operative inquir* or co-operative inquir* (2381)

humanistic or existential or experiential or paradigm* (11017)

field N1 stud* (1269)

field N1 research (306)

human science (132)

biographical method (4)

theoretical sampl* (983)

purpos* N4 sampl* (11299)

focus N1 group* (13775)

account or accounts or unstructured or open-ended or open ended or text* or narrative* (37137)

life world or life-world or conversation analys?s or personal experience* or theoretical saturation (2042)

lived experience* (2170)

life experience* (6236)

cluster sampl* (1411)

theme* or thematic (25504)

observational method* (6607)

questionnaire* (126686)

content analysis (12252)

discourse* N3 analys?s (1341)

discurs* N3 analys?s (35)

constant N1 comparative (3904)

constant N1 comparison (366)

narrative analys?s (312)

Heidegger* (387)

Colaizzi* (387)

Spiegelberg* (0)

van N1 manen* (261)

van N1 kaam* (34)

merleau N1 ponty* (78)

husserl* (106)

Foucault* (253)

Corbin* N2 strauss* (50)

strauss* N2 corbin* (88)

-

glaser* (302)

NOT

TI statistical OR AB statistical

TI regression OR AB regression

TI retrospective OR AB retrospective

TI p-value OR AB p-value

TI p< OR AB p<

TI p< OR AB p<

TI p= OR AB p=

Mega Filter: ISI Web of Science, Social Science Citation Index

TS=interview*

TS=(theme*)

TS=(thematic analysis)

TS=qualitative

TS=nursing research methodology

TS=questionnaire

TS=(ethnograph*)

TS= (ethnonursing)

TS=(ethnological research)

TS=(phenomenol*)

TS=(grounded theor*) OR TS=(grounded stud*) OR TS=(grounded research) OR TS=(grounded analys?s)

TS=(life stor*) OR TS=(women’s stor*)

TS=(emic) OR TS=(etic) OR TS=(hermeneutic) OR TS=(heuristic) OR TS=(semiotic) OR TS=(data saturat*) OR TS=(participant observ*)

TS=(social construct*) OR TS=(postmodern*) OR TS=(post structural*) OR TS=(feminis*) OR TS=(interpret*)

TS=(action research) OR TS=(co-operative inquir*)

TS=(humanistic) OR TS=(existential) OR TS=(experiential) OR TS=(paradigm*)

TS=(field stud*) OR TS=(field research)

TS=(human science)

TS=(biographical method*)

TS=(theoretical sampl*)

TS=(purposive sampl*)

TS=(open-ended account*) OR TS=(unstructured account) OR TS=(narrative*) OR TS=(text*)

TS=(life world) OR TS=(conversation analys?s) OR TS=(theoretical saturation)

TS=(lived experience*) OR TS=(life experience*)

TS=(cluster sampl*)

TS=observational method*

TS=(content analysis)

TS=(constant comparative)

TS=(discourse analys?s) or TS =(discurs* analys?s)

TS=(narrative analys?s)

TS=(heidegger*)

TS=(colaizzi*)

TS=(spiegelberg*)

TS=(van manen*)

TS=(van kaam*)

TS=(merleau ponty*)

TS=(husserl*)

TS=(foucault*)

TS=(42)(42)(42)[42]

TS=(42)(42)(42)[42]

-

TS=(glaser*)

NOT

TS=(p-value)

TS=(retrospective)

TS=(regression)

TS=(statistical)

Suggested Citation

This report should be cited as follows: Brundisini F, Giacomini M, DeJean D, Vanstone M, Winsor S, Smith A. Chronic disease patients’ experiences with accessing health care in rural and remote areas: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser [Internet]. 2013 September;13(15):1-33. Available from: http://www.hqontario.ca/en/documents/eds/2013/full-report-OCDM-rural-health-care.pdf.

Indexing

The Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series is currently indexed in MEDLINE/PubMed, Excerpta Medica/EMBASE, and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination database.

Permission Requests

All inquiries regarding permission to reproduce any content in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series should be directed to: EvidenceInfo@hqontario.ca.

How to Obtain Issues in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series

All reports in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series are freely available in PDF format at the following URL: http://www.hqontario.ca/en/mas/mas_ohtas_mn.html.

Conflict of Interest Statement

All reports in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series are impartial. There are no competing interests or conflicts of interest to declare.

Peer Review

All reports in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series are subject to external expert peer review. Additionally, Health Quality Ontario posts draft reports and recommendations on its website for public comment prior to publication. For more information, please visit: http://www.hqontario.ca/en/mas/ohtac_public_engage_overview.html.

About Health Quality Ontario

Health Quality Ontario (HQO) is an arms-length agency of the Ontario government. It is a partner and leader in transforming Ontario’s health care system so that it can deliver a better experience of care, better outcomes for Ontarians and better value for money.

Health Quality Ontario strives to promote health care that is supported by the best available scientific evidence. HQO works with clinical experts, scientific collaborators and field evaluation partners to develop and publish research that evaluates the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of health technologies and services in Ontario.

Based on the research conducted by HQO and its partners, the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee (OHTAC) — a standing advisory sub-committee of the HQO Board — makes recommendations about the uptake, diffusion, distribution or removal of health interventions to Ontario’s Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, clinicians, health system leaders, and policy-makers.

This research is published as part of Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series, which is indexed in CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Corresponding OHTAC recommendations and other associated reports are also published on the HQO website. Visit http://www.hqontario.ca for more information.

About the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series

To conduct its comprehensive analyses, HQO and/or its research partners reviews the available scientific literature, making every effort to consider all relevant national and international research; collaborates with partners across relevant government branches; consults with clinical and other external experts and developers of new health technologies; and solicits any necessary supplemental information.

In addition, HQO collects and analyzes information about how a health intervention fits within current practice and existing treatment alternatives. Details about the diffusion of the intervention into current health care practices in Ontario add an important dimension to the review. Information concerning the health benefits; economic and human resources; and ethical, regulatory, social, and legal issues relating to the intervention assist in making timely and relevant decisions to optimize patient outcomes.

The public consultation process is available to individuals and organizations wishing to comment on reports and recommendations prior to publication. For more information, please visit: http://www.hqontario.ca/en/mas/ohtac_public_engage_overview.html.

Disclaimer

This report was prepared by HQO or one of its research partners for the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee and developed from analysis, interpretation, and comparison of scientific research. It also incorporates, when available, Ontario data and information provided by experts and applicants to HQO. It is possible that relevant scientific findings may have been reported since completion of the review. This report is current to the date of the literature review specified in the methods section, if available. This analysis may be superseded by an updated publication on the same topic. Please check the HQO website for a list of all publications: http://www.hqontario.ca/en/mas/mas_ohtas_mn_html.

Health Quality Ontario

130 Bloor Street West, 10th Floor

Toronto, Ontario

M5S 1N5

Tel: 416-323-6868

Toll Free: 1-866-623-6868

Fax: 416-323-9261

Email: EvidenceInfo@hqontario.ca

ISSN 1915-7398 (online)

ISBN 978-1-4606-1247-7 (PDF)

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2013

List of Tables

List of Figures

| Figure 1: Study Flow Chart |

List of Abbreviations

- CAD

Coronary artery disease

- CHEPA

Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- EDS

Evidence Development and Standards branch

- HQO

Health Quality Ontario

- OHTAC

Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee

- PATH

Programs for Assessment of Technology in Health Research Institute

- THETA

Toronto Health Economics and Technology Assessment Collaborative

References

- 1.DuPlessis V, Beshiri R, Bollman RD, Clemenson H, et al. Definitions of rural. Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletin. 2001;3(3):17. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada, Catalogue. No. 21-006-XIE. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soanes C, Stevenson A, et al. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press; 2006. Concise Oxford English dictionary. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogers AC, et al. Vulnerability, health and health care. J Adv Nurs. 1997;26(1):65–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997026065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spiers J, et al. New perspectives on vulnerability using emic and etic approaches. J Adv Nurs. 2000;31(3):715–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delor F, Hubert M, et al. Revisiting the concept of ‘vulnerability’. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(11):1557–70. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00465-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watts MJ, Bohle HG, et al. The space of vulnerability: the causal structure of hunger and famine. Progress in Human Geography. 1993;17(1):43–67. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dercon S, et al. Oxford (UK): Queen Elizabeth House, University of Oxford; 2006. Vulnerability: a micro perspective; p. 29. Contract No.: 149. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hurst SA, et al. Vulnerability in research and health care. describing the elephant in the room? Bioethics. 2008;22(4):191–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flaskerud JH, Winslow BJ, et al. Conceptualizing vulnerable populations health-related research. Nurs Res. 1998;47(2):69–78. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199803000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mary CMCR, et al. Vulnerability, vulnerable populations, and policy. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 2004;14(4):411–25. doi: 10.1353/ken.2004.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marmot MG, Wilkinson RG, et al. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press; 2006. Social determinants of health; p. 366. [Google Scholar]

- 12.President’s Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Health Care Industry. Washington (DC): US Government Printing Office; 1998. Jul, Quality first: better healthcare for all Americans [Internet]. Available from: http://archive.ahrq.gov/hcqual/final . [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaw R, Booth A, Sutton A, Miller T, Smith J, Young B, et al. Finding qualitative research: an evaluation of search strategies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2004;4(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilczynski NL, Marks S, Haynes RB, et al. Search strategies for identifying qualitative studies in CINAHL. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(5):705–10. doi: 10.1177/1049732306294515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong SS, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB, et al. Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically relevant qualitative studies in MEDLINE. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2004;107((Pt1)):311–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandelowski M, Barroso J, et al. Creating metasummaries of qualitative findings. Nurs Res. 2003;52(4):226–33. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Toward a metasynthesis of qualitative findings on motherhood in HIV-positive women. Res Nurs Health. 2003;26(2):153–70. doi: 10.1002/nur.10072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandelowski M, Barroso J, et al. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York (NY): Springer Pub. Co. 2006:311. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thorne S, Jenson L, Kearney M, Noblit G, Sandelowski M, et al. Qualitative metasynthesis: reflections on methodological orientation and ideological agenda. Qual Health Res. 2004;14:1342–65. doi: 10.1177/1049732304269888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saini M, Shlonsky A, et al. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2012. Systematic synthesis of qualitative research. Tripodi T, editor; p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corbin JM, Strauss AL, et al. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3rd ed. Los Angeles (CA) Sage Publications Inc. 2008:379. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charmaz K, et al. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London (UK) Sage Publications. 2006:208. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finfgeld DL, et al. Metasynthesis: the state of the art—so far. Qual Health Res. 2003;13(7):893–904. doi: 10.1177/1049732303253462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melia KM, et al. Recognizing quality in qualitative research. In: Bourgeault I, DeVries R, Dingwall R, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications. 2010;559(74) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Finding the findings in qualitative studies. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2002;34(3):213–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noblit G, Hare RD, et al. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park (CA): Sage Publications. 1988:88. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paterson B, et al. In: Reviewing research evidence for nursing practice. Oxford (UK): Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007. Coming out as ill: understanding self-disclosure in chronic illness from a meta-synthesis of qualitative research; pp. 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finfgeld-Connett D, et al. Meta-synthesis of presence in nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2006;55(6):708–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnett-Page E, Thomas J, et al. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9(1):59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodridge D, Hutchinson S, Wilson D, Ross C, et al. Living in a rural area with advanced chronic respiratory illness: a qualitative study. Prim Care Respir J. 2011;20(1):54–8. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2010.00062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.King KM, Thomlinson E, Sanguins J, LeBlanc P, et al. Men and women managing coronary artery disease risk: urban-rural contrasts. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(5):1091–102. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tessaro I, Smith SL, Rye S, et al. Knowledge and perceptions of diabetes in an Appalachian population. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2(2) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Utz SW, Steeves RH, Wenzel J, Hinton I, Jones RA, Andrews D, et al. “Working hard with it”: self-management of type 2 diabetes by rural African Americans. Fam Community Health. 2006;29(3):195–205. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200607000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caldwell PH, Arthur HM, et al. The influence of a “culture of referral” on access to care in rural settings after myocardial infarction. Health Place. 2009;15(1):180–5. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caldwell P, Arthur HM, Rideout E, et al. Lives of rural women after myocardial infarction. Can J Nurs Res. 2005;37(1):54–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berry D, Samos M, Storti S, Grey M, et al. Listening to concerns about type 2 diabetes in an [sic] Native American community. J Cult Divers. 2009;16(2):56–63. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arcury TA, Skelly AH, Gesler WM, Dougherty MC, et al. Diabetes beliefs among low-income, white residents of a rural North Carolina community. J Rural Health. 2005;21(4):337–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barton SS, Anderson N, Thommasen HV, et al. The diabetes experiences of Aboriginal people living in a rural Canadian community. Aust J Rural Health. 2005;13(4):242–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2005.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bird SM, Wiles JL, Okalik L, Kilabuk J, Egeland GM, et al. Living with diabetes on Baffin Island: Inuit storytellers share their experiences. Can J Public Health. 2008;99(1):17–21. doi: 10.1007/BF03403734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tod AM, Lacey EA, McNeill F, et al. ‘I’m still waiting...’: barriers to accessing cardiac rehabilitation services. J Adv Nurs. 2002;40(4):421–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller ST, Marolen KN, Beech BM, et al. Perceptions of physical activity and motivational interviewing among rural African-American women with type 2 diabetes. Women’s Health Issues. 2010;20(1):43–9. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]