ABSTRACT

Purpose: To understand rural community-dwelling older adult participants' shared values, beliefs, and behaviours related to exercise as self-care. Methods: We conducted a constructivist-focused ethnography involving semi-structured interviews and participant observation with 17 individuals 65 years and older. Interviews were transcribed and inductively coded to develop themes related to exercise, self-care, and exercise as self-care. Field notes were triangulated with follow-up interviews and dialogue between authors to enhance interpretation. Results: Participants described exercise broadly as movement and not as a central self-care behaviour. However, awareness of the importance and health-related benefits of exercise increased after a significant personal health-related event. Participants preferred exercise that was enjoyable and previously experienced. Conclusions: Prescribing exercise for older adults may be particularly effective if the focus is on enjoyable and previously experienced physical activity and if it incorporates interpretation of exercise guidelines and training principles in relation to chronic conditions and potential health benefits.

Key Words: ethnology, aged, exercise, self-care

RÉSUMÉ

Objectif : Comprendre les valeurs, les croyances et les comportements partagés des participants adultes âgés vivant dans des logements communautaires en ce qui concerne l'exercice comme soins autodirigés. Méthode : Nous avons procédé à une ethnographie convergente constructiviste comportant des entrevues semi-structurées et l'observation de participants, qui a porté sur 17 personnes de 65 ans et plus. Les entrevues ont été transcrites et codées de façon inductive de façon à dégager des thèmes liés à l'exercice, aux soins autodirigés et à l'exercice comme soins autodirigés. On a comparé les notes pratiques aux entrevues de suivi et au dialogue entre les auteurs afin d'améliorer l'interprétation. Résultats : Les participants ont décrit l'exercice de façon générale comme le fait de bouger et non un comportement central des soins autodirigés. La sensibilisation à l'importance de l'exercice et à ses bienfaits pour la santé a toutefois augmenté après un événement important lié à la santé personnelle. Les participants préféraient un exercice agréable et qu'ils connaissaient déjà. Conclusions : Il peut être particulièrement efficace de prescrire des exercices à des adultes âgés si l'on vise une activité physique agréable et déjà connue et si l'activité consiste aussi à interpréter des lignes directrices sur l'exercice et des principes d'entraînement par rapport à des problèmes chroniques et à des bienfaits possibles pour la santé.

Mots clés : anthropologie, culturel, méthodes de physiothérapie, âgé, exercice, soins autodirigés

More than 70% of Canadians age 60 years or older are reported to have at least one chronic health condition.1 The impact of chronic disease is greater for older adults living in rural areas than for those in urban centres,2 as both health status and health service access are poorer in rural areas.3 At the federal level, helping rural-residing Canadians with health care is a long-standing priority,3 and provincial governments, including Nova Scotia and Ontario, currently view chronic disease as a priority health care issue, advocating self-care as the prevailing approach.4,5

Exercise as self-care refers to purposeful physical activity of a certain type, intensity, and duration to reach a sufficient level of exertion to improve health or, for example, to prevent exacerbation of chronic disease.6 There is strong evidence for the benefits of exercise in improving functional mobility in chronically ill populations.7 Unfortunately, only 37.67% to 47.29% of Canadian older adults are sufficiently physically active to meet guidelines for health benefits.8

Exercise behaviour is thought to be influenced by individual characteristics6 such as age and health; characteristics of both sociocultural and physical environments6; and personal or shared attitudes, values, and beliefs, such as self-efficacy.9 Self-efficacy, or the belief that one can perform a given behaviour, is an important predictor of human behaviour,10,11 as described in social cognitive theory (SCT).9 Also inherent to SCT is the reciprocal influence of cultural values, beliefs, and physical activity experiences.12 For older adults in rural Canada, insufficient activity levels may partly reflect a sociocultural context that strongly values physical work and productivity and accords less priority to leisure-time (i.e., non-work-related) physical activity.13 Seeking to understand personal characteristics and sociocultural contexts of rural community-dwelling older adults could enable physiotherapists to design and prescribe exercise interventions that are more likely to be adhered to by this group. The purpose of our study, therefore, was to understand rural community-dwelling older adults' shared values, beliefs, and behaviours related to exercise as self-care.

Methods

Ethnography provides a means to gain an understanding of how members of a group make sense of their world by exploring their shared values, beliefs, and behaviours.14 Compared to traditional ethnographies, focused ethnography draws more heavily on interviewing than on participant observation to explore a single concept in a relatively short time frame.15 Our study used constructivist-focused ethnography to understand the concept of exercise as understood and enacted by rural community-dwelling older adults within the sociocultural context of a Canadian Maritime rural community. This rural community is a coastal summer tourist destination where more than a third of residents are older than 65 years. The constructivist paradigmatic underpinnings16 of this study assume that how a concept is understood, valued, and enacted varies according to an individual's sociocultural location and experiences, and that members of particular cultural groups may, over time, develop shared understandings by way of social interaction. Participants acted as co-constructors to cooperatively create an understanding of the concepts of exercise, self-care, and exercise as self-care.16 To enhance methodological rigour, we paid consistent attention to transcendent criteria for trustworthiness, described by Morrow17 (summarized in Box 1). The study was approved by the University of Western Ontario Research Ethics Board.

Box 1.

Transcendent Criteria for Trustworthiness

| Criterion | Description |

|---|---|

| Social validity* | Research goals are socially significant; data collection/analysis procedures are appropriate; the effects of the study results are important |

| Subjectivity and reflexivity | Researchers embrace their positioning as co-constructors of meaning and engage in reflexivity by keeping an ongoing record of “experiences, reactions, and … assumptions or biases”18(p.254) to inform the analysis process and/or critical discussion with peer researchers and participants regarding correction, direction, and feedback on interpretations of findings† |

| Adequacy of data | Various types/sources of information are used; sufficient time is spent in the setting to build rapport; evidence is gathered until no new or disconfirming evidence emerges |

| Adequacy of interpretation | Analytic framework is well articulated; researchers' interpretations of the findings and supporting quotations are balanced; interpretations describing how data were integrated are clear and insightful |

Reflexivity

The investigators are both physiotherapists trained in qualitative methods of interview and analysis. The primary researcher (LG) grew up in the Maritimes and lived and worked in the investigated setting for more than three summers. She engaged in researcher reflexivity18 by maintaining a journal of her field experiences, including participant observation,20 informal discussions, and participants' postures or gestures during interviews; she shared the journal with the co-investigator (DC) to acknowledge and discuss her influence on the interpretation of the findings.

Procedure

The primary investigator engaged in participant observation of older adults' daily activities in public spaces (e.g., trail walks or waterfront activities) and in informal discussions with local leaders from the community centre, churches, and local businesses. These initial steps were conducted to understand possible contextual influences on residents' perceptions of exercise, as well as locally available health and exercise services. Participant recruitment was facilitated by local leaders and supplemented by snowball sampling and posted advertisements. Based on a review of health-related focused ethnographies,21–23 we estimated that a sample of 15–20 participants would be sufficient to achieve the depth of understanding required. Community residents >65 years who lived on their own or with family, but not in an assisted-living or nursing home, were considered eligible to participate.

Each participant completed two audio-taped interviews with LG at a location of their choosing, individually or with their spouse if both had consented to participate. Interviews were guided by questions focused on understanding the participant's engagement in and perceptions of exercise and self-care, such as “What do you do to take care of yourself?” and “What does it mean to you to exercise?” (see Appendix 1 for interview guide). Audio recordings were transcribed and analyzed using inductive coding methods.24 Each transcript was reviewed line by line to identify statements and phrases relevant to the study's purpose. Statements were sorted into similar groupings or themes based on patterns in thoughts and behaviours, and interview data were triangulated20 with participant observation field notes. Interview summaries and preliminary themes were shared with participants during second interviews to ensure that the themes extracted resonated with participants and to provide an opportunity for discussion and clarification. Finally, we discussed the transcripts to refine themes and choose quotations to support our interpretations.

Results

Setting

At the time of the study, the local community centre ran programmes and social events to support older adults and encourage community participation. The same building housed a small independent gym equipped with weightlifting and aerobic training equipment. The closest hospitals were 11–17 km away in neighbouring townships. Public transportation was not locally available. Instead, participants who were unable to drive enlisted family and friends or relied on taxis from neighbouring towns. Participants expressed an interest in getting fresh air and commented on the ease of getting about their town, the availability of sidewalks, trails, and relatively flat terrain, and the local scenery, including the waterfront.

Participant demographics

A total of 17 community residents volunteered to participate in the study, provided written informed consent, and were interviewed twice. The majority of participants were in their 70s and had some post-secondary education, two or more chronic diseases, and few mobility challenges (see Table 1). All participants engaged in some form of regular physical activity, from walking in apartment hallways with a walker to walking 13 km daily along a wooded trail. Six participants were interviewed simultaneously with their spouses, and the remaining 11 were interviewed individually.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Participant | Age, gender | Years as resident | Living arrangement | Education | Gait aid | Diagnosed chronic disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 69, W | 1.5 | S, Apt | Post 2° | DM | |

| P2 | 68, M | 45 | S, House | Some 2° | V | |

| P3 | 73, W | 30 | A, House | Grad | V | |

| P4 | 77, W | 20 | S, Apt | Post 2° | C+ | V, DM, CV, MSK |

| P5 | 78, M | 20 | S, Apt | Some 2° | V, CV | |

| P6 | 75, M | 4 | S, House | Grad | CV | |

| P7 | 67, W | 4 | S, House | Post 2° | ||

| P8 | 65, M | 12 | S, House | Post 2° | ||

| P9 | 72, M | 39 | S, Apt | Grad | V, CR | |

| P10 | 92, W | 25 | A, House | Post 2° | V, CV | |

| P11 | 71, W | 40 | A, Apt | Post 2° | C | V, CV, MSK, O |

| P12 | 69, M | 1.5 | S, Apt | Some 2° | V, CR, CV, MSK | |

| P13 | 88, M | 5 | A, House | Post 2° | O | |

| P14 | 67, W | 63 | S, House | Some 2° | V, MSK | |

| P15 | 71, M | 50 | S, House | 2° | V, DM, CV | |

| P16 | 71, W | 16 | S, Apt | Grad | CR, MSK | |

| P17 | 89, W | 89 | A, Apt | Post 2° | C++, W+, WC | V, DM, CR, CV, MSK |

| Mean/Mode |

74.2 |

27 |

Post 2° |

2 |

||

| Total | 8 M | 492 | 5 A, 8 Apt | 3 with aids |

W=women; S=living with spouse; Apt=living in apartment or condo; Post 2°=undergraduate or professional programme not taught in an academic institution (e.g., nurse, secretary); DM=diabetes (Type I or II not specified); M=men; 2°=high school; V=vision-related conditions (e.g., macular degeneration); A=living alone; Grad=master's or doctoral degree; C+=cane used daily; CV=cardiovascular conditions (e.g., atrial fibrillation); MSK=musculoskeletal conditions (e.g., osteoporosis, arthritis); CR=cardio-respiratory conditions (e.g., asthma, emphysema); C=cane used occasionally; O=other health conditions (e.g., hearing impairment); C++=cane used always; W+=walker used daily; WC=wheelchair used occasionally.

Participants' shared values, beliefs, and behaviours

Three primary characteristics emerged from the interview transcripts and participant observation field notes to represent shared values, beliefs, and behaviours among the participants: being with others, independence, and sense of community. These characteristics were relevant within the sociocultural context and to the interpretation of the main themes (described below) concerning exercise and self-care.

In the discussion below, participant numbers are keyed to Table 1.

Being with others

Participants spoke about the joy of meeting new people and spending time with friends, spouses, pets, and neighbours while exercising. They also talked about the importance of having someone to go with for a walk or to the gym, both as a motivation to persist with the activity and as a source of safety. P1, who goes to the local gym, said, “I go to the gym with somebody and that's always nice, you know, to have somebody to encourage you even if you don't feel like going …”

Independence

Participants operationalized independence as functional capacity and self-reliance (i.e., not needing help from others). They explained their rationale for walking long distances and doing their own laundry as a way to demonstrate that they can still do things by themselves. P11 explained, “… it's important to do something for yourself and not to just let yourself be a victim …” When asked what types of help he was receiving from family or friends, P12 said simply, “I'm very independent.”

Sense of community

A strong sense of belonging or investment in and ownership of the community was characterized by three values shared among the group: the importance of helping others, loyalty to what was local, and the convenience of what was local. All participants volunteered in the community; many mentioned the importance of doing more to help others because they had the functional capacity to do so, emphasizing the value participants placed on their independence. P13, who lived on his own in a split-level home, explained why he feels the need to help others:

I feel I should be helping. I'm very fortunate in having good health and being able to live as I do … No question about it, I should do more … I owe the community, I owe my friends … I'm damn lucky, at 88 years of age to be able to move around like I do [and] participate in things I enjoy.

A loyalty to what was local within the community was evident when participants indicated their preference for supporting the waterfront and the people who own the local deli, gym, and café versus the larger grocery stores in neighbouring towns and the international franchise gym. P12 explained why he supports and volunteers at the local deli:

I do it for [the deli owner] because … she was born and raised in [this town] and she is a local girl, and you just have no idea the money that she donates to people on a daily basis. She helps a lot of people … she gives a lot of soul and we give a lot back to her.

The value placed on the convenience of what was local was revealed through participants' comparisons to other neighbouring communities that are faster-paced or have steeper hills and no sidewalks. Participants said they enjoyed being able to walk to their local gym, post office, grocery store, waterfront, and wooded trails but disliked having to go into neighbouring towns to access public health services, such as a cardiac rehabilitation programme:

I wouldn't live in [the neighbouring town] for a bit because of all the hills … I don't really want to drive all the way out to [another town] three times a week, and we try to stay away from [there] as much as we can—we're not crazy about it … we stay away from it, because we like it down around here. (P1)

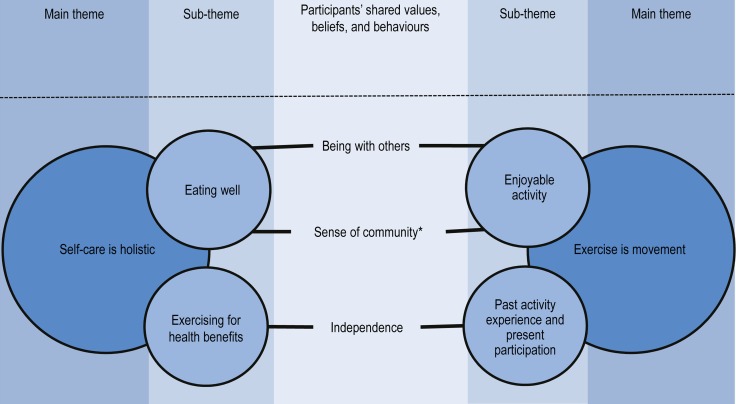

Main themes

Two main themes, each with two sub-themes, emerged from the analysis. The first main theme is self-care is holistic, with the sub-themes eating well and exercising for health benefits. The second main theme is exercise is movement, with the sub-themes enjoyable activity and past activity experience and present participation. The interaction between these themes and the participants' shared values, beliefs, and behaviours is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Graphic representation of the interaction between main and sub-themes with participants' shared values, beliefs, and behaviours within the community (setting) where the study was conducted. This is not meant to be used for reproduction in another setting.

*Sense of community includes three sub-themes: importance of helping others, convenience of what was local, and loyalty to what was local.

Self-care is holistic

When asked what they did to take care of themselves, participants spoke to multiple strategies, conveying a holistic view of self-care. Some participants referred to avoiding the sun or wearing sunscreen; others spoke of regular sleep, personal hygiene, taking medications as prescribed, or finding and using appropriate over-the-counter cold and flu medication. However, the most commonly mentioned self-care behaviour (by 14 participants), and the first response from 10 participants, was eating well or eating healthily. Since exercise was the study's focus, probes were used during interviews to stimulate participants to talk about exercise if they did not independently raise it as a means to self-care.

Eating well

Participants mentioned removing specific foods from their diet because of allergies or age-related digestive changes and opting for regular meals with lots of vegetables. Participants with diabetes described their ability to care for themselves by choosing or avoiding certain types of food (e.g., refined sugar), reading labels, and monitoring the quantity consumed. Those with macular degeneration described their efforts to seek and over-consume foods rich in vitamin A:

I eat pounds and pounds of raw carrots, and I try to eat a lot of broccoli and things that are good for your eyes … I have that all the time and I'm trying now to wean myself away from coffee because I was finding that I was getting [an] allergy…. I was starting to itch and I had a history of allergies when I was in my twenty-five [to] thirties … and it took me about a year to get over it, so I know what I'm allergic to, so I just have to be more cautious that's all … I just have to be moderate. Moderation—my dad used to say—moderation in all things, and that's true. (P3)

Food appeared to be a significant aspect of this group's culture, as food or eating and dining were often described as a way to spend time with others and to demonstrate a strong sense of community by helping others. Some described the gift of food as a way to meet and communicate with neighbours, as a way to come together with friends by bringing food to functions, and as a reason to gather with others. Those who described food as a means of helping others enjoyed cooking for others and noted that they give back to their community in part through their volunteer roles for local food and church programmes. When asked about their daily life, many described dining out with friends and family as a treat or as a form of recreation: “I eat well. I eat properly. Being a diabetic I have to … We eat out an awful lot, so that's kind of entertainment for us. When you are retired you can do that” (P1).

Exercising for health benefits

Participants described many health benefits of exercise in relation to their personal health problems. Exercise was said to decrease blood glucose levels, blood pressure, and cholesterol; improve heart and lung function; increase heart rate; improve circulation for healing; improve balance “when your feet are bad” (P6); improve muscle mass and reduce “flab”; and improve weight control. Improved mobility, fitness, and agility were also perceived as health benefits of being active. Other non-specific health benefits included improving kidney and bowel function, controlling pain, and perspiring to “unload toxins” (P14). P10 describes her understanding of the health benefits resulting from exercise:

When my knee started giving me trouble … I thought that I better strengthen the ligaments and muscles around it, so I started walking more … If you are fortunate enough to be able to do it, I think that it does alleviate a lot of the physical stresses. [Of] course it helps your circulation. I think it will help to keep your weight under control and hopefully it helps to keep your lungs [working] …

A common experience in the group was the occurrence of a significant personal life event that caused participants to realize the importance of exercise in relation to their own health. With the exception of P8 and P17, every participant shared a significant life event that explained their increased awareness of the health benefits of exercise, including neurovascular and cardiac health events (stroke, myocardial infarction), chronic pain, musculoskeletal injury, and weight gain. P7 and P11 noted that after becoming exhausted from walking during holidays, they realized that they needed to do something to make themselves stronger and independent if they were to continue going on vacations. P10 describes her experience following a back injury at work when she was younger:

I wasn't in[to] barbells then, I was working in a [nursery] … and I pulled my back so I went to [the] doctor … I was living outside of [the city] at that point, and he said, “Well, I think you might have to have your back fused or you must do these exercises every day, and if you don't want to do either of those you must find another doctor.” I did the exercises every day and I've done them ever since.

Exercise is movement

Participants described exercise as a very broad and unstructured activity involving movement; they concluded that some types of exercise are better than others, but any exercise is better than none. Exercise was described as anything that makes “your body feel tired at the end of the day” (P3) and involves moving arms and legs. P2 said, “I think getting up off of the couch is exercise … any movement at all is exercise.” Some more specific examples included dancing, going to the gym, swimming, and doing boat maintenance. With the exceptions of P8 and P9, all agreed that their paid jobs (before retirement) were exercise; for example, some participants were retired educators, health care workers, or manual labourers. With the exceptions of P8 and P16, all reported that walking to the post office or doing an errand was exercise. P16 explained, “Well, I don't count running errands as walking because you can't really feel the stride and enjoy walking. I just feel that when you walk, you should just walk. Because I'm doing errands, I'm doing things all over the house, but that doesn't really count [as exercise].”

Participants noted that some types of exercise are superior to others: going to the gym is better than walking (or vice versa), running is better than walking, walking outdoors is better than walking indoors, lifting weights is better than doing aerobic activity, swimming in the ocean is better than swimming in a pool, and moving faster is better than moving slower. Although most agreed that any exercise is better than none, some did indicate that a certain distance or at least half an hour is needed to gain improvement. When probed to articulate why some types of exercise were better than others, participants revealed that these conclusions were not based primarily on what they felt provided the superior or more effective health benefit; rather, what exercise they described as better depended on how enjoyable they found the activity and whether they did that activity when they were younger—that is, it depended on their past activity experience and present participation. P12 explains why he feels that walking and taking the stairs is better exercise than going to the gym:

I do exercise, I don't go to a gym … I don't like them. I use the stairs more often … We'll take [our dog] and go to the beaches and do the walk thing … [The gym] is too regimented for me. I just don't like that you've got to be there at eleven and someone tells you what to do; and I'm just not that kind of person … I played badminton this winter for the first time in a long time … I really enjoyed it, and if there's a pool available someplace, I like to swim.

Enjoyable activity

Participants explained that they chose to participate in activities that felt good to them in some way. P5 explained, “It has to be something that you can enjoy. If it was work then you wouldn't do it.” P13, who is a self-identified poor golfer, explained that he continues to play golf every week with his friends because he has a great time doing it. P16 spoke about why she enjoys walking along the trails through the woods:

Walking is exercise, and I'd rather get my exercise through something like that where there's something so exciting that you go for three hours and you don't even know you've done it. I mean your whole body is completely rejuvenated because your blood is rushing through it, but that's great.

What made these activities enjoyable for some participants was being with others. Many participants explained that they would rather exercise at the gym than exercise at home alone; some reported that they choose to attend group exercise classes or walk to the waterfront, where there will be other people around, because they enjoy meeting new people.

Past activity experience and present participation

Participants explained that in their generation it was not typical to go out to exercise for the sake of exercise. Those who still engaged in running or an organized sport, such as golf or curling, did so because they had participated in these activities in their youth. Sports they had enjoyed in their youth changed as they got older; for example, walking replaced running. For others, participation in particular activities or sports changed or was discontinued as a result of children, retirement, or the onset of disease. P9 described his experience as a youth and reflected on how his past activity experience has influenced his present participation and how that might be relevant to other older adults:

When I was in university for two years, I did go to the gym … Body building was becoming significant and there were various guys who were writing books and photographs all over the place, and gyms were starting to appear … I did [lift weights] and I knew what [body building] was about. I knew how to do it … I wasn't ashamed to be doing it … [Now] I can get up and go for a walk and not feel “stumbly,” so that's a major aspect of this [exercise] strategy … I'm starting to realize that it's lucky that I did that as a youth, because it's very hard for a mature person who hasn't done that to even imagine it's worth doing … I'm one of the best arguments for that kind of training in the elderly, and I'll make the argument to anybody.

Discussion

This study addressed older adults' perceptions of purposeful exercise for self-care within a rural Canadian Maritime context by examining the sociocultural characteristics of the sampled setting and of the participants. Independence, a sense of community, and being with others were shared, important, and defining group characteristics. This study found that these characteristics, which are known to be defining features of older adults across rural Canada,2 influence self-care and exercise behaviours.

Participants valued many activities as self-care, but eating well appeared to be the most important. They described the importance of food quality and quantity and the relationship between ingredients or nutrient sources and the progression of diseases. Participants agreed that exercise provides health benefits but did not describe it as a primary means of self-care. Participation in exercise and awareness of its importance for self-care grew following a significant health event, injury, or disease onset, but participants did not articulate the importance of matching activity to their personal health conditions for specific health benefits. These findings are similar to those of a large-scale study of older adults' perceptions of how physical activity and diet affect brain health.25 Participants from the brain health study were able to articulate how to modify dietary practices to support brain health by, for example, controlling portions and increasing their consumption of fish and vegetables. However, despite agreeing that physical activity is beneficial for brain health, they did not demonstrate a good understanding of the recommended frequency, intensity, type, and duration of exercise needed to gain benefit.25 Another recent study concluded that participants, including healthy young adults and older adults attending chronic disease rehabilitation programmes, were largely unaware of the Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines.26 Given physiotherapists' expertise in prescribing exercise and promoting self-management of chronic diseases,27 physiotherapists can enhance participants' understanding of exercise as self-care by explaining physiologic training principles and interpreting exercise guidelines, such as the Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines for Older Adults,28 to help them get the most out of their efforts to exercise for health benefits.

Our study provides a contextual example of why it is important for physiotherapists to understand and incorporate knowledge of what activities their older clients enjoy and have done previously when encouraging exercise for self-care. Physiotherapists can use specific outcome measures and theoretical frameworks to integrate this knowledge and understanding of their clients during exercise prescription. In our study, participants described exercise as a broad concept that includes a variety of movements, activities of daily living, and sports; they also preferred activities that they found enjoyable and that they had previously experienced. Prior research has demonstrated that perceived enjoyment is a significant motivator for physical activity participation among older adults29 and can be measured using a valid and reliable outcome measure such as the Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale.30,31 In our study, we found that being with others made exercise enjoyable and motivated participants to persist in the activity. From a social cognitive perspective, being with others (for social support) and previous experiences influence self-efficacy, which in turn influences exercise behaviour.9 Social cognitive theory (SCT) also describes a reciprocal influence between cultural values, beliefs, physical activity experiences, and individuals' lifestyles.12 Research informed by SCT hypothesizes that older adults are more likely to be motivated to be physically active if they “value physical activity as a meaningful behaviour.”12,32(p.83) Occupational therapy researchers have demonstrated this effect among older adult women33 and advocate for integrating meaningful activity when interpreting physical activity guidelines with clients.34 Future research in physiotherapy could employ SCT as a framework to design meaningful, context-specific therapeutic exercise interventions that may better facilitate engagement and adherence to therapeutic exercise as a means to self-care.35

A limitation of our study is that the literature suggests that participants interviewed with their spouses may have divulged less36 than they would have if interviewed independently; interviewing participants independently might have helped to further enrich or “thicken”37 their descriptions of exercise as self-care.

Conclusion

Participants in our study valued independence, community, and being with others. Participants' understanding of eating well as self-care was more specific and readily articulated than their understanding of exercise as self-care. Participants described exercise in very broad terms, from “any movement at all” to specific sport examples. Based on personal enjoyment and past experiences, they believed that some types of exercise are better than others. As experts in exercise prescription and self-management promotion, physiotherapists can enhance participants' understanding of exercise as self-care by educating them about exercise guidelines and physiologic training principles. This study provides a contextual example that supports the importance of understanding both older adults' past experiences with exercise and what they enjoy doing or find meaningful and incorporating this understanding into treatment interventions to encourage routine exercise as self-care.

Key Messages

What is already known on this topic

Exercise as self-care is advocated as an approach to chronic disease management; however, older adults are not sufficiently active to gain health benefits. Personal, sociocultural, and environmental factors influence exercise participation.

What this study adds

This study highlights the need to interpret training principles and exercise guidelines in relation to specific health conditions and the importance of understanding and integrating the activities older people enjoy and have previously experienced when designing interventions to promote exercise as self-care.

Appendix 1

Interview Guide

Initial interview

The initial interview was conducted in a conversational manner. Upon receiving the participant's informed consent and completed demographic questionnaire, the interview was mediated by the following questions:

What is your daily life like here in this community?

What do you do to take care of yourself?

What does it mean to you to exercise?

In what ways has your involvement in what you see as exercise changed as you got older? In what ways has it stayed the same over time?

In what ways has your perception of what exercise is for you changed as you got older? In what ways has it stayed the same over time?

What activities are you involved with in the community? (e.g., community centre, church groups)

What is your role or how are you involved with programmes in the community?

What types of help are you receiving from friends, family, neighbours, or community members?

What types of help are you giving to your friends, family, neighbours, or community members?

Follow-up interview

The following is an example of what was asked in the follow-up interview:

Last time we met this is what we talked about … [summary of conversation] … based on what you have told me, I came up with these themes that I think represent what you were saying [review themes with participant]. Does this resonate with what you were trying to say?

Would you please elaborate on the point you made about [insert point here]?

Is there anything else you would like to add about exercise and what it means to you in your daily life?

Physiotherapy Canada 2013; 65(4);333–341; doi:10.3138/ptc.2012-31

References

- 1.Broemeling AM, Watson DE, Prebtani F. Population patterns of chronic health conditions, co-morbidity and healthcare use in Canada: implications for policy and practice. Healthc Q. 2008;11(3):70–6. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2008.19859. Medline:18536538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keating N, Swindle J, Fletcher S. Aging in rural Canada: a retrospective and review. Can J Aging. 2011;30(3):323–38. doi: 10.1017/S0714980811000250. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0714980811000250. Medline:21767464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romanow RJ. Final report. Ottawa (ON): Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada; 2002. [cited 2013 May 9]. Building on values: the future of health care in Canada. commissioner. Report No.: CP32-85/2002E-IN. Available from: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/CP32-85-2002E.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Unit for Population Health and Chronic Disease Prevention on Behalf of Working Group Members. Nova Scotia chronic disease prevention strategy [Internet] Halifax: Dalhousie University; 2003. [cited 2012 June]. Available from: http://www.gov.ns.ca/hpp/cdip/cd-prevention-strategy.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Preventing and managing chronic disease: Ontario's framework [Internet] Toronto: Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2007. [cited 2012 Jun]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/program/cdpm/index.html#1. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ulbrich SL. Nursing practice theory of exercise as self-care. Image J Nurs Sch. 1999;31(1):65–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1999.tb00423.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.1999.tb00423.x. Medline:10081215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rejeski WJ, Mihalko SL. Physical activity and quality of life in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(Suppl 2):23–35. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.suppl_2.23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.suppl_2.23. Medline:11730235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Statistics Canada. Physical activity during leisure time, 2010. Canadian Community Health Survey [Internet] 2010. [cited 2013 Jan]. [updated 2011 Jul 28]. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-625-x/2011001/article/11467-eng.htm.

- 9.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191. Medline:847061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gellert P, Ziegelmann JP, Schwarzer R. Affective and health-related outcome expectancies for physical activity in older adults. Psychol Health. 2012;27(7):816–28. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.607236. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2011.607236. Medline:21867397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schutzer KA, Graves BS. Barriers and motivations to exercise in older adults. Prev Med. 2004;39(5):1056–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.003. Medline:15475041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: WH Freeman and Co; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Witcher CS, Holt NL, Spence JC, et al. A case study of physical activity among older adults in rural Newfoundland, Canada. J Aging Phys Act. 2007;15(2):166–83. doi: 10.1123/japa.15.2.166. Medline:17556783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagy Hesse-Biber S, Leavy P. Ethnography. In: Nagy Hesse-Biber S, Leavy P, editors. The practice of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2006. pp. 229–78. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muecke MA. On the evaluation of ethnographies. In: Morse JM, editor. Critical issues in qualitative research methods. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 1994. pp. 187–209. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ponterotto J. Qualitative research in counselling psychology: a primer on research paradigms and philosophy of science. J Couns Psychol. 2005;52(2):126–36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.126. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morrow SL. Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counselling psychology. J Couns Psychol. 2005;52(2):250–60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.250. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finlay L. “Outing” the researcher: the provenance, process, and practice of reflexivity. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(4):531–45. doi: 10.1177/104973202129120052. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/104973202129120052. Medline:11939252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolf MM. Social validity: the case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. J Appl Behav Anal. 1978;11(2):203–14. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1978.11-203. http://dx.doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1978.11-203. Medline:16795590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fetterman DM. Ethnography: step-by-step. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crosato KE, Ward-Griffin C, Leipert B. Aboriginal women caregivers of the elderly in geographically isolated communities. [cited 2012 May];Rural Remote Health [Internet] 2005 7(4):796. Available from: http://www.rrh.org.au/home/defaultnew.asp. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Resnick B. Motivation in geriatric rehabilitation. J Nurs Scholarsh. 1996;28(1):41–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1996.tb01176.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.1996.tb01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robbins LK. A focused ethnographic study of women in recovery from alcohol abuse [dissertation] Austin: University of Texas; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyatizis RE. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilcox S, Sharkey JR, Mathews AE, et al. Perceptions and beliefs about the role of physical activity and nutrition on brain health in older adults. Gerontologist. 2009;49(Suppl 1):S61–71. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp078. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnp078. Medline:19525218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berry TR, Witcher C, Holt NL, et al. A qualitative examination of perceptions of physical activity guidelines and preferences for format. Health Promot Pract. 2010;11(6):908–16. doi: 10.1177/1524839908325066. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1524839908325066. Medline:19116420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Accreditation Council for Canadian Physiotherapy Academic Programs; Canadian Alliance of Physiotherapy Regulators; Canadian Physiotherapy Association; Canadian Council of Physiotherapy University Programs. Essential competency profile for physiotherapists in Canada [Internet] Toronto: National Physiotherapy Advisory Group; 2009. Oct, [cited 2012 September]. Available from: http://www.physiotherapyeducation.ca/Resources/Essential%20Comp%20PT%20Profile%202009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tremblay MS, Warburton DE, Janssen I, et al. New Canadian physical activity guidelines. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011;36(1):36–46. 47–58. doi: 10.1139/H11-009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/H11-009. Medline:21326376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dacey M, Baltzell A, Zaichkowsky L. Older adults' intrinsic and extrinsic motivation toward physical activity. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32(6):570–82. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.6.570. Medline:18442337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mullen SP, Olson EA, Phillips SM, et al. Measuring enjoyment of physical activity in older adults: invariance of the physical activity enjoyment scale (paces) across groups and time. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8(1):103. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-8-103. Medline:21951520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kendzierski D, DeCarlo KJ. Physical activity enjoyment scale: two validation studies. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1991;13(1):50–64. [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Brien Cousins S. Grounding theory in self-referent thinking: conceptualizing motivation for older adult physical activity. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2003;4(2):81–100. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1469-0292(01)00030-9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagstaff S. Supports and barriers for exercise participation for well elders: implications for occupational therapy. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 2006;24(2):19–33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/J148v24n02_02. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Handcock P, Tattersall K. Occupational therapists beware: physical activity guidelines can mislead. Br J Occup Ther. 2012;75(2):111–3. http://dx.doi.org/10.4276/030802212X13286281651270. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sirur R, Richardson J, Wishart L, et al. The role of theory in increasing adherence to prescribed practice. Physiother Can. 2009;61(2):68–77. doi: 10.3138/physio.61.2.68. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/physio.61.2.68. Medline:20190989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yorgason JB, Roper SO, Wheeler B, et al. Older couples' management of multiple-chronic illnesses: individual and shared perceptions and coping in type 2 diabetes and osteoarthritis. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28(1):30–47. doi: 10.1037/a0019396. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0019396. Medline:20438201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geertz C. The interpretation of cultures: selected essays. New York: Basic Books; 1973. Thick description: toward an interpretive theory of culture; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]