Abstract

Background

Dyspepsia is a condition defined by chronic pain or discomfort in the upper gastrointestinal tract that can be caused by Helicobacter pylori. The carbon-13 urea breath test (13C UBT) is a non-invasive test to detect H. pylori.

Objectives

We aimed to determine the diagnostic accuracy and clinical utility of the 13C UBT in adult patients with ulcer-like dyspepsia who have no alarm features.

Data Sources

A literature search was performed using Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid Embase, the Wiley Cochrane Library, and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination database, for studies published between 2003 and 2012.

Review Methods

We abstracted the sensitivity and specificity, which were calculated against a composite reference standard. Summary estimates were obtained using bivariate random effects regression analysis.

Results

From 19 diagnostic studies, the 13C UBT summary estimates were 98.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 96.3–99.0) for sensitivity and 95.1% (95% CI, 90.3–97.6) for specificity. In 6 studies that compared the 13C UBT with serology, the 113C UBT sensitivity was 95.0% (95% CI, 90.1–97.5) and specificity was 91.6 % (95% CI, 81.3–96.4). The sensitivity and specificity for serology were 92.9% (95% CI, 82.6–97.3) and 71.1% (95% CI, 63.8–77.5), respectively. In 1 RCT, symptom resolution, medication use, and physician visits were similar among the 13C UBT, serology, gastroscopy, or empirical treatment arms. However, patients tested with 13C UBT reported higher dyspepsia-specific quality of life scores.

Limitations

Processing of the 13C UBT results can vary according to many factors. Further, the studies showed significant heterogeneity and used different composite reference standards.

Conclusions

The 13C UBT is an accurate test with high sensitivity and specificity. Compared with serology, it has higher specificity. There is a paucity of data on the 13C UBT beyond test accuracy.

Plain Language Summary

Breath test for detecting bacteria in patients with ulcer-like symptoms

Dyspepsia is a condition that causes long-term pain or discomfort in the upper abdomen. Symptoms can include heartburn, burping, bloating, nausea, or slow digestion. Dyspepsia can be caused by a bacterium that also causes ulcers and stomach cancer. Half of the world’s people are believed to be infected with these bacteria. A test has been developed to detect the bacteria in a breath sample. Our review determined the accuracy of this breath test in adults with ulcer-like symptoms.

From 19 studies, the breath test correctly identified 98% of patients with the bacteria and 95% of patients without the bacteria, as determined by a reference standard. Six studies compared the breath test to a blood test that is currently used. Both the breath and blood tests performed well in correctly identifying patients with the bacteria. However, the blood test was incorrectly positive in 20 more patients who did not have the bacteria according to the breath test. This means that more patients would have received unnecessary treatment.

Thus, the breath test is an accurate test to detect the bacteria in adult patients who have ulcer-like symptoms. But the many differences among the studies in our review included several steps taken to perform the breath test and the reference standards used to compare a blood test with the breath test.

Background

Objective of Analysis

We aimed to determine the diagnostic accuracy and clinical utility of the carbon-13 urea breath test (13C UBT) for detection of Helicobacter pylori infection in adult patients with uninvestigated ulcer-like dyspepsia and who have no alarm features, for whom endoscopy is not indicated.

Clinical Need and Target Population

Description of Condition

Dyspepsia is a condition of the upper gastrointestinal tract that causes such symptoms as heartburn, acid regurgitation, excessive belching, abdominal bloating, nausea, abnormal or slow digestion, and early satiety. (1) Dyspepsia can have many underlying causes, including infection with H. pylori.

Global Prevalence and Incidence

The prevalence of H. pylori in the world has been estimated to be as much as 50%. (2) Developing countries have a higher burden of infection than developed countries. Infection with the bacteria is an important cause of chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and gastric cancer. H. pylori is a class I carcinogen according to the World Health Organization. (3)

Ontario Prevalence and Incidence

In Ontario, the prevalence of H. pylori is 23% according to a published study. (4) The study found that men were more likely to be infected than women. Older age and immigration were also important risk factors for infection. Further, dyspepsia has been shown to affect 29% of Canadians in a population-based survey, and half of them reported chronic symptoms. (5) Approximately 30% of dyspeptic patients in primary care are infected with H. pylori. (6)

Technology/Technique

Detection of H. pylori can rely on invasive, endoscopy-based methods (e.g., culture, histology, or rapid urease test) or non-invasive tests. Endoscopy is clinically indicated for elderly patients or patients of any age who present with alarm features: weight loss, abdominal mass, dysphagia, persistent vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding, or anemia. (1)

There are 3 main types of non-invasive tests: serology, stool antigen, and UBT. Serologic testing, which relies on the detection of antibodies in the blood, is the currently funded first-line diagnostic test in Ontario. The UBT relies on the ability of H. pylori to convert into carbon dioxide urea that has been labelled with isotopes and then ingested by the patient. The difference in carbon dioxide levels between the baseline breath sample (before ingestion of urea) and the postadministration breath sample is detected by specialized measuring equipment (e.g., mass spectrometer or infrared spectrophotometer). (7)

Urea can be labelled with either the 13C or 14C isotope. The 14C isotope is mildly radioactive and not recommended for children or pregnant women. (8) The 13C isotope is not radioactive and thus is more frequently used. Another advantage of the UBT is that it can be used to evaluate the success or failure of eradication therapy, whereas serology results can remain positive for an extended period even after successful treatment. (9)

Regulatory Status

The protocol for performing the 13C UBT can vary according to many factors, including use of a citric acid test meal, dose of urea, time of breath collection, measuring equipment, or test cut-off value. (8) Two commercial kits with standardized protocols are licensed by Health Canada. The Helikit 13C breath test kit is a class 2 device (licence number 805) manufactured by IsoDiagnostika, a division of Paladin Labs Inc. (Edmonton, Alberta) and is licensed to detect H. pylori as the causative organism in peptic ulcers. The Dia13-Helico Breath Test Kit (licence number 64105) is a class 2 device manufactured by R.A.D. Diagnostics (St-Laurent, Quebec) and is also licensed to detect H. pylori.

Evidence-Based Analysis

Research Question

What is the diagnostic accuracy and clinical utility of the 13C UBT for detecting H. pylori in adults with uninvestigated ulcer-like dyspepsia who have no alarm features?

Research Methods

Literature Search

Search Strategy

A literature search was performed on December 14, 2012, using Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid Embase, the Wiley Cochrane Library, and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination database, for studies published from January 1, 2003, until December 14, 2012. (Appendix 1 provides details of the search strategies.) Abstracts were reviewed by a single reviewer and, for those studies meeting the eligibility criteria, full-text articles were obtained. Reference lists were also examined for any additional relevant studies not identified through the search.

Inclusion Criteria

full reports in English;

studies published between January 1, 2003, and December 14, 2012;

studies that include adult patients with ulcer-like dyspepsia and without alarm features;

studies that evaluate the 13C UBT as a first-line diagnostic test or post-treatment test;

studies that used endoscopy-based methods as the reference standard, with agreement on at least 2 tests.

Exclusion Criteria

studies with only children or elderly patients,

studies where data to calculate sensitivity and specificity could not be abstracted,

studies using a single test as the reference standard.

Outcomes of Interest

sensitivity and specificity,

effect on patient management or clinical decision-making,

patient-important outcomes.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (LR+), and negative likelihood ratio (LR–) for cross-sectional studies of accuracy. Sensitivity is the proportion of positive test results among patients with the disease. Specificity is the proportion of negative test results among those without the disease. The LR+ measures how more frequent a positive test is found in diseased versus non-diseased patients. On the other hand, the LR– measures whether a negative result is more likely to be found in diseased than in non-diseased patients.

Summary estimates were obtained using bivariate random-effects regression analysis in Stata (10) with the user-written program “metandi.” (11) This method assumes that the sensitivity and specificity data undergoing logit-transformation from individual studies are normally distributed around a mean value with a certain amount of variability around this mean. (12) The potential presence of a negative correlation between sensitivity and specificity within studies is addressed by explicitly incorporating this correlation into the analysis. The combination of the 2 normally distributed outcomes, the sensitivity and specificity data undergoing logit-transformation, and the possible correlation between them, leads to the bivariate normal distribution. (12)

Summary measures were calculated using this random-effects approach to account for the heterogeneity among studies and to better enable comparisons between different tests. These estimates were also used as inputs into the economic model.

In addition, we performed the summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve analysis. (13) The SROC curve displays each study’s sensitivity and specificity within the receiver operating characteristic space. A regression curve is fitted through the distribution of pairs of sensitivity and specificity. The area under the curve (AUC) measures the overall accuracy of diagnostic tests. The forest plots and SROC curves were created using Meta-DiSc software. (14)

Quality of Evidence

The quality of the body of evidence for each outcome was examined according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group criteria. (15) The overall quality was determined to be high, moderate, low, or very lowthrough use of a step-wise, structural method.

Study design was the first consideration; the starting assumption was that randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are high quality, whereas observational studies are low quality. Five additional factors—risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias—were then taken into account. Limitations in these areas resulted in downgrading the quality of evidence. Finally, 3 main factors that could raise the quality of evidence were considered: large magnitude of effect, dose response gradient, and accounting for all residual confounding factors. (15) For more detailed information, please refer to the latest series of GRADE articles. (15)

As stated by the GRADE Working Group, the final quality score can be interpreted using the following definitions:

| High | Very confident that the true effect lies close to the estimate of the effect |

| Moderate | Moderately confident in the effect estimate—the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different |

| Low | Confidence in the effect estimate is limited—the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect |

| Very Low | Very little confidence in the effect estimate—the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect |

Results of Evidence-Based Analysis

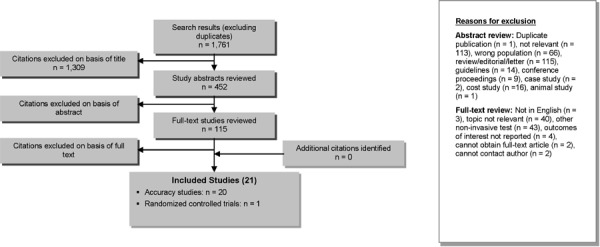

The database search yielded 1,761 citations published between January 1, 2003, and December 14, 2012 (with duplicates removed). Articles were excluded on the basis of information in the title and abstract. The full texts of potentially relevant articles were obtained for further assessment. Figure 1 shows the breakdown of when and for what reason citations were excluded in the analysis.

Figure 1: Citation Flow Chart.

Twenty-one studies (19 diagnostic accuracy studies, 1 post-treatment accuracy study, and 1 RCT) met the inclusion criteria. The reference lists of health technology assessments were hand searched to identify any additional potentially relevant studies, and no additional citations were found.

Sensitivity and specificity were calculated against a composite reference standard consisting of at least 2 tests. While several different reference standards were found in the included studies, the most common one was based on the culture result and, if this was negative, then concordance on histology and the rapid urease test. Nine of the 19 diagnostic accuracy studies reported results using this reference standard.

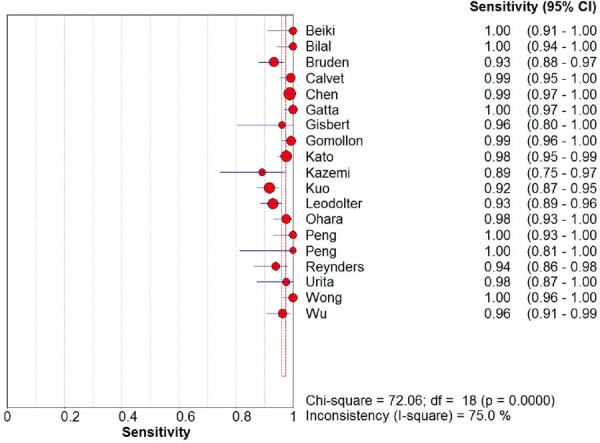

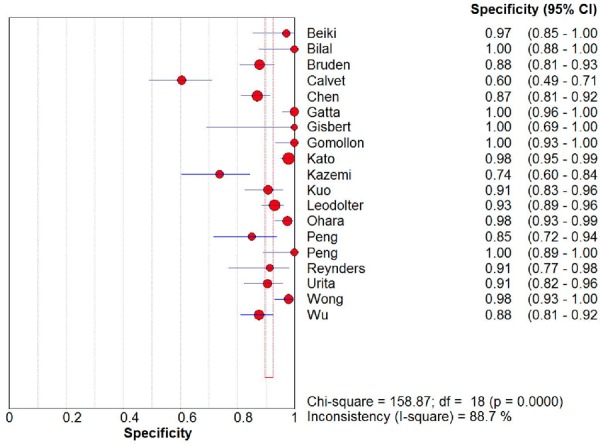

From the 19 diagnostic accuracy studies, the summary estimates of the 13C UBT were 98.1% (95% CI, 96.3%–99.0%) for sensitivity and 95.1% (95% CI, 90.3%–97.6%) for specificity (Figures 2 and 3). The summary LR+ and LR– estimates were 19.9 (95% CI, 9.9–39.9) and 0.02 (95% CI, 0.01–0.04), respectively. The AUC was 98.8% (95% CI, 97.4%–100%).

Figure 2: Sensitivity Estimates from 19 Diagnostic Studies of Carbon-13 Urea Breath Test.

Figure 3: Specificity Estimates from 19 Diagnostic Studies of Carbon-13 Urea Breath Test.

In 6 studies that compared the 13C UBT to serology in head-to-head trials (16–21), the sensitivity for 13C UBT was 95.0% (95% CI, 90.1%–97.5%) and specificity was 91.6% (95% CI, 81.3%–96.4%). The LR+ and LR– were 11.3 (95% CI, 4.8–26.6) and 0.05 (95% CI, 0.03–0.11), respectively. The AUC was 97.3% (95% CI, 95.2%–99.4%).

The performance of serologic tests was lower when compared directly to the 13C UBT. The sensitivity for serology was 92.9% (95% CI, 82.6%–97.3%) and specificity was 71.1% (95% CI, 63.8%–77.5%). The LR+ and LR– were 3.2 (95% CI, 2.4–4.3) and 0.10 (95% CI, 0.04–0.28), respectively. The AUC was 91.9% (95% CI, 83.7%–100%).

Two studies (including 1 study with both diagnostic and post-treatment accuracy data) evaluated the performance of the 13C UBT to assess treatment eradication, which occurred when culture, histology, and rapid urease test results were all negative. In the first study of 109 patients with dyspepsia who were administered the 13C UBT 4 to 6 weeks after therapy, the sensitivity was 100% (95% CI, 85.2%–100%), and the specificity was 100% (95% CI, 95.8%–100%). (22) In the second study of 325 gastroenterology referrals, the sensitivity was 98.9% (95% CI, 94.2%–100%), and the specificity was 99.6% (95% CI, 97.6%–100%). (23)

In a small RCT that compared management strategies for patients with dyspepsia and no alarm symptoms in a primary care setting, patients were randomized to empirical therapy with a histamine receptor antagonist (n = 11), serologic testing (n = 8), 13C UBT testing (n = 11), or gastroscopy (n = 13). (24) Resolution of symptoms at 6 weeks and 6 months was similar across all the management arms (P = 0.49), and there were also no differences for medication use or number of physician visits. Pairwise comparisons among the various strategies showed that patients in the 13C UBT group had higher dyspepsia-specific, health-related quality of life scores than those receiving empirical therapy (P = 0.007), serology (P = 0.01), and gastroscopy (P = 0.02)

For each included study, the study design was identified and is summarized below in Table 1, which is a modified version of a hierarchy of study design by Goodman. (25) Table 2 summarizes guidelines for uninvestigated dyspepsia in various countries.

Table 1: Body of Evidence Examined According to Study Design.

| Study Design | Number of Eligible Studies |

|---|---|

| RCTs | |

| Systematic review of RCTs | |

| Large RCT | |

| Small RCT | 1 |

| Observational Studies | |

| Systematic review of non-RCTs with contemporaneous controls | |

| Non-RCT with non-contemporaneous controls | |

| Systematic review of non-RCTs with historical controls | |

| Non-RCT with historical controls | |

| Database, registry, or cross-sectional study | 20 |

| Case series | |

| Retrospective review, modelling | |

| Studies presented at an international conference | |

| Expert opinion | |

| Total | 21 |

Abbreviation: RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Conclusions

The 13C UBT is an accurate test with high sensitivity and high specificity for both diagnostic and treatment monitoring.

In head-to-head comparisons with serology, the 13C UBT has comparable sensitivity but higher specificity.

There is no standardized protocol for performing the non-commercial 13C UBT, and the procedure can vary according to many factors.

Further, the studies that evaluated the performance of the 13C UBT used different composite reference standards.

There is a paucity of data on the use of the 13C UBT beyond test accuracy.

Existing Guidelines for Technology

Table 2: Comparison of Guidelines for Uninvestigated Dyspepsia in Various Countries.

| Country | Guidelines |

|---|---|

| Canada (26) | Test and treat if patient < 50 years and has no alarm symptomsa; UBT is the diagnostic test of first choice, while there is insufficient evidence to recommend the stool antigen test (27) |

| United States (28) | Test and treat if patient < 55 years of age and has no alarm symptoms; UBT and stool antigen test are the diagnostic tests of choice |

| Europe (29) | Test and treat if patient has no alarm symptoms; UBT and stool antigen test are the diagnostic tests of choice |

| Asia Pacific (30) | Test and treat if patient has no alarm symptoms; UBT and stool antigen test are the diagnostic tests of choice |

Abbreviation: UBT, urea breath test.

Alarm symptoms include weight loss, presence of abdominal mass, dysphagia, persistent vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding, or anemia.

Acknowledgements

Medical Information Services

Corinne Holubowich, BEd, MLIS

Kellee Kaulback, BA(H), MISt

Editorial Staff

Elizabeth Jean Betsch, ELS

Pierre Lachaine

Clinical Experts

Michael Gould, MD, FRCPC

Assistant Professor, University of Toronto

Clinical Lead, Cancer Care Ontario Colon Check Program

Medical Director, Vaughan Endoscopy Clinic

David Tannenbaum, MD, CCFP, FCFP

Associate Professor, University of Toronto

Family Physician-in-Chief, Mount Sinai Hospital

Past President, Ontario College of Family Physicians

Appendices

Appendix 1: Literature Search Strategies

Search date: December 14, 2012

Databases searched: Ovid MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, Embase, Cochrane Library, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination

Q: What is the diagnostic accuracy and clinical utility of Urea Breath Test in adults with suspected dyspepsia with Helicobacter pylori, compared to endoscopy and other tests?

Limits: 2003-current; English; Humans

Filters: None

Database: Ovid MEDLINE® <1946 to November Week 3 2012>, Ovid MEDLINE® In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations <December 13, 2012>, Embase <1980 to 2012 Week 49>

Search Strategy:

| # | Searches | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | exp Helicobacter pylori/ | 68439 |

| 2 | Helicobacter Infections/ use mesz | 23191 |

| 3 | exp Helicobacter infection/ use emez | 19241 |

| 4 | ((helicobacter or campylobacter or h) adj2 pylori*).ti,ab. | 72636 |

| 5 | or/1-4 | 84474 |

| 6 | exp Breath Tests/ use mesz | 10521 |

| 7 | exp urea breath test/ use emez | 1916 |

| 8 | breath analysis/ use emez | 10074 |

| 9 | (urea adj2 breath*).ti,ab. | 5551 |

| 10 | (carbon* adj2 urea).ti,ab. | 434 |

| 11 | (CUBT* or UBT* or 13C or 14C).ti,ab. | 164413 |

| 12 | (Helikit* or Meretek* UBT or PYtest* or UBIT* or Helibactertest*).ti,ab. | 70 |

| 13 | or/6-12 | 182311 |

| 14 | 5 and 13 | 7415 |

| 15 | limit 14 to english language | 6438 |

| 16 | limit 15 to human | 5881 |

| 17 | limit 16 to yr=”2003 -Current” | 2955 |

| 18 | remove duplicates from 17 | 1795 |

Cochrane.

| ID | Search | Hits |

| #1 | MeSH descriptor: [Helicobacter pylori] explode all trees | 1829 |

| #2 | MeSH descriptor: [Helicobacter Infections] explode all trees | 1784 |

| #3 | ((helicobacter or campylobacter or h) near/2 pylori*):ti (Word variations have been searched) | 2676 |

| #4 | #1 or #2 or #3 | 2947 |

| #5 | MeSH descriptor: [Breath Tests] explode all trees | 1159 |

| #6 | (urea near/2 breath*) or (carbon* near/2 urea):ti (Word variations have been searched) | 78 |

| #7 | (CUBT* or UBT* or 13C or 14C):ti (Word variations have been searched) | 204 |

| #8 | (Helikit* or Meretek* UBT or PYtest* or UBIT* or Helibactertest*):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 1 |

| #9 | #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 | 1314 |

| #10 | #4 and #9 from 2003 to 2012 | 129 |

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination.

| Line | Search | Hits |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | MeSH DESCRIPTOR helicobacter pylori EXPLODE ALL TREES | 257 |

| 2 | MeSH DESCRIPTOR helicobacter infections EXPLODE ALL TREES | 248 |

| 3 | ((helicobacter or campylobacter or h) adj2 pylori*):TI | 229 |

| 4 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 | 288 |

| 5 | MeSH DESCRIPTOR breath tests EXPLODE ALL TREES | 50 |

| 6 | ((urea adj2 breath*) or (carbon* adj2 urea)):TI | 8 |

| 7 | (CUBT* or UBT* or 13C or 14C):TI | 4 |

| 8 | (Helikit* or Meretek* UBT or PYtest* or UBIT* or Helibactertest*):TI | 0 |

| 9 | #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 | 52 |

| 10 | #4 AND #9 | 29 |

| 11 | (#10):TI FROM 2003 TO 2012 | 18 |

Appendix 2: GRADE Tables

Table A1: GRADE Evidence Profile for Accuracy Studies.

| Number of Studies (Design) | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 (accuracy) | No serious limitations | Serious limitations (–1)a | Serious limitations (–1)b | No serious limitations | Undetected | ⊕⊕ Low |

Significant heterogeneity present in summary estimates of sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratios.

Test accuracy is only a surrogate for patient-important outcomes.

Table A2: Risk of Bias Among Randomized Controlled Trials for Comparison of Management Strategies.

| Author, Year | Allocation Concealment | Blinding | Complete Accounting of Patients and Outcome Events | Selective Reporting Bias | Other Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuddihy et al, 2005 (24) | No limitations | Limitationsa | No limitations | No limitations | Limitationsb |

Blinding of management strategy was impossible for patients and providers.

Outcomes on resolution of symptoms, medication use, physician visits, and dyspepsia-specific quality of life were patient reported.

Appendix 3: Summary Table

Table A3: Data from Studies Included in Review.

| Author, Year | Country | Study Design | Sample Size | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beiki et al, 2005 (31) | Iran | Cross-sectional | 76 patients with dyspepsia | TP = 40, FP = 1, FN = 0, TN = 35 |

| Bilal et al, 2007 (32) | Pakistan | Cross-sectional | 90 symptomatic patients | TP = 62, FP = 0, FN = 0, TN = 28 |

| Bruden et al, 2011 (16) | USA | Cross-sectional | 280 patients undergoing endoscopy | TP = 139, FP = 16, FN = 10, TN = 115 |

| Calvet et al, 2009 (33) | Spain | Cross-sectional | 199 patients with dyspepsia | TP = 117, FP = 32, FN = 1, TN = 49 |

| Chen et al, 2003 (34) | Taiwan | Cross-sectional | 554 patients undergoing endoscopy | TP = 365, FP = 24, FN = 4, TN = 161 |

| Gatta et al, 2003 (22) | Italy | Cross-sectional | 200 patients with dyspepsia | TP = 113, FP = 0, FN = 0, TN = 87 |

| 109 post-treatment patients | TP = 23, FP = 0, FN = 0, TN = 86 | |||

| Gisbert et al, 2003 (35) | Spain | Cross-sectional | 36 patients with dyspepsia | TP = 25, FP = 0, FN = 1, TN = 10 |

| Gomollon et al, 2003 (17) | Spain | Cross-sectional | 194 patients with dyspepsia | TP = 139, FP = 0, FN = 1, TN = 54 |

| Kato et al, 2004 (36) | Japan | Cross-sectional | 505 patients undergoing endoscopy | TP = 252, FP = 5, FN = 6, TN = 242 |

| Kazemi et al, 2011 (18) | Iran | Cross-sectional | 94 patients with dyspepsia | TP = 33, FP = 15, FN = 4, TN = 42 |

| Kuo et al, 2005 (37) | Taiwan | Cross-sectional | 317 patients with dyspepsia | TP = 211, FP = 8, FN = 19, TN = 79 |

| Leodolter et al, 2003 (19) | Europe | Cross-sectional | 415 patients with dyspepsia | TP = 198, FP = 14, FN = 15, TN = 188 |

| Manes et al, 2005 (23) | Italy | Cross-sectional | 325 gastroenterology referralsa | TP = 93, FP = 1, FN = 1, TN = 230 |

| Ohara et al, 2004 (38) | Japan | Cross-sectional | 251 patients undergoing endoscopy | TP = 125, FP = 3, FN = 3, TN = 120 |

| Peng et al, 2005 (39) | Taiwan | Cross-sectional | 50 patients undergoing endoscopy | TP = 18, FP = 0, FN = 0, TN = 32 |

| Peng et al, 2009 (20) | Taiwan | Cross-sectional | 100 patients undergoing endoscopy | TP = 53, FP = 7 FN = 0, TN = 40 |

| Reynders et al, 2012 (21) | Belgium | Cross-sectional | 117 patients with dyspepsia | TP = 77, FP = 3, FN = 5, TN = 32 |

| Urita et al, 2004 (40) | Japan | Cross-sectional | 127 patients undergoing endoscopy | TP = 41, FP = 8, FN = 1, TN = 77 |

| Wong et al, 2003 (41) | Hong Kong | Cross-sectional | 200 patients with dyspepsiab | TP = 99, FP = 2, FN = 0, TN = 99 |

| Wu et al, 2006 (42) | Taiwan | Cross-sectional | 254 patients with dyspepsiac | TP = 105, FP = 18, FN = 4, TN = 127 |

| Cuddihy et al, 2005 (24) | USA | Randomized controlled trial | 43 patients randomized to 1 of 4 different management strategies | Resolution of symptoms, medication use, and number of visits were similar across all arms; 13C UBT group had higher dyspepsia-specific, quality of life scores than other arms |

Abbreviations: FP, false–positive results; FN, false–negative results; TN, true–negative results; TP, true–positive results.

Study evaluated accuracy in post-treatment patients only.

Study included 50 post-treatment patients.

Study included 67 post-treatment patients.

Suggested Citation

This report should be cited as follows:

Ling D. Carbon-13 urea breath test for Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with uninvestigated ulcer-like dyspepsia: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assessment Series [Internet]. 2013 October;13(19):1-30. Available from: http://www.hqontario.ca/en/documents/eds/2013/full-report-urea-breath-test.pdf.

Indexing

The Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series is currently indexed in MEDLINE/PubMed, Excerpta Medica/Embase, and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination database.

Permission Requests

All inquiries regarding permission to reproduce any content in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series should be directed to: EvidenceInfo@hqontario.ca.

How to Obtain Issues in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series

All reports in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series are freely available in PDF format at the following URL: http://www.hqontario.ca/evidence/publications-and-ohtac-recommendations/ontario-health-technology-assessment-series.

Conflict of Interest Statement

All reports in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series are impartial. There are no competing interests or conflicts of interest to declare.

Peer Review

All reports in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series are subject to external expert peer review. Additionally, Health Quality Ontario posts draft reports and recommendations on its website for public comment prior to publication. For more information, please visit: http://www.hqontario.ca/evidence/evidence-process/evidence-review-process/professional-and-public-engagement-and-consultation.

About Health Quality Ontario

Health Quality Ontario is an arms-length agency of the Ontario government. It is a partner and leader in transforming Ontario’s health care system so that it can deliver a better experience of care, better outcomes for Ontarians and better value for money.

Health Quality Ontario strives to promote health care that is supported by the best available scientific evidence. The Evidence Development and Standards branch works with expert advisory panels, scientific collaborators, and field evaluation partners to conduct evidence-based reviews that evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of health interventions in Ontario.

Based on the evidence provided by Evidence Development and Standards and its partners, the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee— a standing advisory subcommittee of the Health Quality Ontario Board—makes recommendations about the uptake, diffusion, distribution, or removal of health interventions to Ontario’s Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, clinicians, health system leaders, and policy-makers.

Health Quality Ontario’s research is published as part of the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series, which is indexed in MEDLINE/PubMed, Excerpta Medica/Embase, and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination database. Corresponding Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee recommendations and other associated reports are also published on the Health Quality Ontario website. Visit http://www.hqontario.ca for more information.

About the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series

To conduct its comprehensive analyses, Evidence Development and Standards and its research partners review the available scientific literature, making every effort to consider all relevant national and international research; collaborate with partners across relevant government branches; consult with expert advisory panels, clinical and other external experts, and developers of health technologies; and solicit any necessary supplemental information.

In addition, Evidence Development and Standards collects and analyzes information about how a health intervention fits within current practice and existing treatment alternatives. Details about the diffusion of the intervention into current health care practices in Ontario add an important dimension to the review.

The Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee uses a unique decision determinants framework when making recommendations to the Health Quality Ontario Board. The framework takes into account clinical benefits, value for money, societal and ethical considerations, and the economic feasibility of the health care intervention in Ontario. Draft Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee recommendations and evidence-based reviews are posted for 21 days on the Health Quality Ontario website, giving individuals and organizations an opportunity to provide comments prior to publication. For more information, please visit: http://www.hqontario.ca/evidence/evidence-process/evidence-review-process/professional-and-public-engagement-and-consultation.

Disclaimer

This report was prepared by Health Quality Ontario or one of its research partners for the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee and was developed from analysis, interpretation, and comparison of scientific research. It also incorporates, when available, Ontario data and information provided by experts and applicants to Health Quality Ontario. It is possible that relevant scientific findings may have been reported since the completion of the review. This report is current to the date of the literature review specified in the methods section, if available. This analysis may be superseded by an updated publication on the same topic. Please check the Health Quality Ontario website for a list of all publications: http://www.hqontario.ca/evidence/publications-and-ohtac-recommendations.

Health Quality Ontario

130 Bloor Street West, 10th Floor

Toronto, Ontario

M5S 1N5

Tel: 416-323-6868

Toll Free: 1-866-623-6868

Fax: 416-323-9261

Email: EvidenceInfo@hqontario.ca

ISSN 1915-7398 (online)

ISBN 978-1-4606-2711-2 (PDF)

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2013

List of Tables

| Table 1: Body of Evidence Examined According to Study Design |

| Table 2: Comparison of Guidelines for Uninvestigated Dyspepsia in Various Countries |

| Table A1: GRADE Evidence Profile for Accuracy Studies |

| Table A2: Risk of Bias Among Randomized Controlled Trials for Comparison of Management Strategies |

| Table A3: Data from Studies Included in Review |

List of Figures

List of Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under the curve

- C

Carbon

- CI

Confidence interval

- HQO

Health Quality Ontario

- LR

Likelihood ratio

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- SROC

Summary receiver operating characteristic

- UBT

Urea breath test

References

- 1.Veldhuyzen Van Zanten SJ, Flook N, Chiba N, Armstrong D, Barkun A, Bradette M, et al. An evidence-based approach to the management of uninvestigated dyspepsia in the era of Helicobacter pylori. Canadian Dyspepsia Working Group. CMAJ. 2000 Jun 13;162((12 Suppl)):S3–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cave DR. How is Helicobacter pylori transmitted? Gastroenterology. 1997 Dec;113((6 Suppl)):S9–14. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)80004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The International Agency for Research on Cancer. Schistosomes, Liver, Flukes and Helicobacter pylori. Lyon, France: IARC Press; IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. 1994. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Naja F, Kreiger N, Sullivan T. Helicobacter pylori infection in Ontario: prevalence and risk factors. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007 Aug;21(8):501–6. doi: 10.1155/2007/462804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tougas G, Chen Y, Hwang P, Liu MM, Eggleston A. Prevalence and impact of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the Canadian population: findings from the DIGEST study. Domestic/International Gastroenterology Surveillance Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999 Oct;94(10):2845–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomson AB, Barkun AN, Armstrong D, Chiba N, White RJ, Daniels S, et al. The prevalence of clinically significant endoscopic findings in primary care patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia: the Canadian Adult Dyspepsia Empiric Treatment - Prompt Endoscopy (CADET-PE) study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003 Jun 15;17(12):1481–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perri F, Festa V, Clemente R, Quitadamo M, Andriulli A. Methodological problems and pitfalls of urea breath test. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998 Oct;30 Suppl 3:S315–S319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gisbert JP, Pajares JM. Review article: 13C-urea breath test in the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection -- a critical review. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004 Nov 15;20(10):1001–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas RE, Croal BL, Ramsay C, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Effect of enhanced feedback and brief educational reminder messages on laboratory test requesting in primary care: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2006 Jun 17;367(9527):1990–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68888-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Intercooled STATA (for Windows) [computer program]. Version 12. College Station: TX: StataCorp;; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harbord RM. metandi: Stata module for meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy. Statistical Software Components, Boston College Department of Economics. Revised. Apr 15, 2008.

- 12.Reitsma JB, Glas AS, Rutjes AW, Scholten RJ, Bossuyt PM, Zwinderman AH. Bivariate analysis of sensitivity and specificity produces informative summary measures in diagnostic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005 Oct;58(10):982–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Littenberg B, Moses LE. Estimating diagnostic accuracy from multiple conflicting reports: a new meta-analytic method. Med Decis Making. 1993 Oct;13(4):313–21. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9301300408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zamora J, Abraira V, Muriel A, Khan K, Coomarasamy A. Meta-DiSc: a software for meta-analysis of test accuracy data. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6(31) doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schunemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knottnerus A. GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011 Apr;64(4):380–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruden DL, Bruce MG, Miernyk KM, Morris J, Hurlburt D, Hennessy TW, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of tests for Helicobacter pylori in an Alaska Native population. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(42):4682–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i42.4682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomollon F, Ducons JA, Santolaria S, Lera O, I, Guirao R, Ferrero M, et al. Breath test is very reliable for diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in real clinical practice. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35(9):612–8. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(03)00373-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kazemi S, Tavakkoli H, Habizadeh MR, Emami MH. Diagnostic values of Helicobacter pylori diagnostic tests: stool antigen test, urea breath test, rapid urease test, serology and histology. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16(9):1097–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leodolter A, Vaira D, Bazzoli F, Schutze K, Hirschl A, Megraud F, et al. European multicentre validation trial of two new non-invasive tests for the detection of Helicobacter pylori antibodies: urine-based ELISA and rapid urine test. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18(9):927–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peng N-J, Lai K-H, Lo G-H, Hsu P-I. Comparison of noninvasive diagnostic tests for Helicobacter pylori infection. Med Princ Pract. 2009;18(1):57–61. doi: 10.1159/000163048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reynders MBML, Deyi VYM, Dahma H, Scheper T, Hanke M, Decolvenaer M, et al. Performance of individual Helicobacter pylori antigens in the immunoblot-based detection of H. pylori infection. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2012;64(3):352–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gatta L, Vakil N, Ricci C, Osborn JF, Tampieri A, Perna F, et al. A rapid, low-dose, 13C-urea tablet for the detection of Helicobacter pylori infection before and after treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17(6):793–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manes G, Zanetti MV, Piccirillo MM, Lombardi G, Balzano A, Pieramico O. Accuracy of a new monoclonal stool antigen test in post-eradication assessment of Helicobacter pylori infection: comparison with the polyclonal stool antigen test and urea breath test. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37(10):751–5. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuddihy MT, Locke GR, III, Wahner-Roedler D, Dierkhising R, Zinsmeister AR, Long KH, et al. Dyspepsia management in primary care: a management trial. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59(2):194–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2005.00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodman C. Literature searching and evidence interpretation for assessing health care practices. Stockholm, Sweden: Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care. 1996. p. 81. SBU Report No. 119E. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Hunt R, Thomson AB. Canadian Helicobacter pylori consensus conference. Canadian Association of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 1998 Jan;12(1):31–41. doi: 10.1155/1998/170180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hunt R, Fallone C, Veldhuyzan van ZS, Sherman P, Smaill F, Flook N, et al. Canadian Helicobacter Study Group Consensus Conference: update on the management of Helicobacter pylori--an evidence-based evaluation of six topics relevant to clinical outcomes in patients evaluated for H pylori infection. Can J Gastroenterol. 2004 Sep;18(9):547–54. doi: 10.1155/2004/326767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Talley NJ. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2005 Nov;129(5):1753–5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon ATR, Bazzoli F, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection - The Maastricht IV/ Florence consensus report. Gut. 2012;61(5):646–64. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fock KM, Katelaris P, Sugano K, Ang TL, Hunt R, Talley NJ, et al. Second Asia-Pacific Consensus Guidelines for Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24(10):1587–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beiki D, Khalaj A, Dowlatabadi R, Eftekhari M, Hossein MHA, Fard A, et al. Validation of 13C-urea breath test with non dispersive isotope selective infrared spectroscopy for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection: a survey in Iranian population. Daru. 2005;13(2):52–5. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bilal R, Khaar B, Qureshi TZ, Mirza SA, Ahmad T, Latif Z, et al. Accuracy of non-invasive 13C-Urea Breath Test compared to invasive tests for Helicobacter pylori detection. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2007;17(2):84–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calvet X, Sanchez-Delgado J, Montserrat A, Lario S, Ramirez-Lazaro MJ, Quesada M, et al. Accuracy of diagnostic tests for Helicobacter pylori: a reappraisal. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(10):1385–91. doi: 10.1086/598198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen TS, Chang FY, Chen PC, Huang TW, Ou JT, Tsai MH, et al. Simplified 13C-urea breath test with a new infrared spectrometer for diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18(11):1237–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.03139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gisbert JP, Ducons J, Gomollon F, Dominguez-Munoz JE, Borda F, Mino G, et al. Validation of the 13c-urea breath test for the initial diagnosis of helicobacter pylori infection and to confirm eradication after treatment. Revista espanola de enfermedades digestivas. 2003;95(2):121–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kato M, Saito M, Fukuda S, Kato C, Ohara S, Hamada S, et al. 13C-Urea breath test, using a new compact nondispersive isotope-selective infrared spectrophotometer: comparison with mass spectrometry. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39(7):629–34. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1357-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuo F-C, Wang S-W, Wu I-C, Yu F-J, Yang Y-C, Wu J-Y, et al. Evaluation of urine ELISA test for detecting Helicobacter pylori infection in Taiwan: a prospective study. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(35):5545–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i35.5545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohara S, Kato M, Saito M, Fukuda S, Kato C, Hamada S, et al. Comparison between a new 13C-urea breath test, using a film-coated tablet, and the conventional 13C-urea breath test for the detection of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39(7):621–8. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1356-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peng NJ, Lai KH, Liu RS, Lee SC, Tsay DG, Lo CC, et al. Capsule 13C-urea breath test for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(9):1361–4. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i9.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Urita Y, Hike K, Torii N, Kikuchi Y, Kanda E, Kurakata H, et al. Breath sample collection through the nostril reduces false-positive results of 13C-urea breath test for the diagnosis of helicobacter pylori infection. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36(10):661–5. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong WM, Lam SK, Lai KC, Chu KM, Xia HHX, Wong KW, et al. A rapid-release 50-mg tablet-based 13C-urea breath test for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17(2):253–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu I-C, Wang S-W, Yang Y-C, Yu F-J, Kuo C-H, Chuang C-H, et al. Comparison of a new office-based stool immunoassay and 13C-UBT in the diagnosis of current Helicobacter pylori infection. J Lab Clin Med. 2006;147(3):145–9. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]