The crystallization of acetyl-CoA hydrolase from N. meningitidis is reported.

Keywords: acetyl-CoA hydrolase, thioesterase, hotdog fold, Neisseria meningitidis

Abstract

Neisseria meningitidis is the causative microorganism of many human diseases, including bacterial meningitis; together with Streptococcus pneumoniae, it accounts for approximately 80% of bacterial meningitis infections. The emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains of N. meningitidis has created a strong urgency for the development of new therapeutics, and the high-resolution structural elucidation of enzymes involved in cell metabolism represents a platform for drug development. Acetyl-CoA hydrolase is involved in multiple functions in the bacterial cell, including membrane synthesis, fatty-acid and lipid metabolism, gene regulation and signal transduction. Here, the first recombinant protein expression, purification and crystallization of a hexameric acetyl-CoA hydrolase from N. meningitidis are reported. This protein was crystallized using the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion technique at pH 8.5 and 290 K using ammonium phosphate as a precipitant. Optimized crystals diffracted to 2.0 Å resolution at the Australian Synchrotron and belonged to space group P213 (unit-cell parameters a = b = c = 152.2 Å), with four molecules in the asymmetric unit.

1. Introduction

Neisseria meningitidis is a Gram-negative, diplococcal obligate human pathogen which can cause bacterial meningitis, pneumonia, septic arthritis, meningococcemia and sepsis. Worldwide, almost half of the cases of meningococcal disease are acute bacterial meningitis, and in adults N. meningitidis and Streptococcus pneumoniae together cause 80% of cases (World Health Organization Initiative for Vaccine Research, 2013 ▶). Bacterial meningitis persists as a major danger to global health, with 50 000 deaths annually worldwide and many more resulting in neurological disorders. This bacterium is easily transmitted through person-to-person contact, aerosol droplets or contact with respiratory secretions from asymptomatic carriers, and up to 5–10% of the population are carriers of N. meningitidis (Cohn & Jackson, 2012 ▶; Molesworth et al., 2003 ▶). The development of new therapeutics to treat emerging antibiotic-resistant strains of N. meningitidis is of high importance, and crystallization of proteins to enable high-resolution crystallographic structure determination represents a strong platform for rational drug design. Here, we report the first recombinant protein expression, purification and crystallization of a hexameric acetyl-CoA hydrolase from N. meningitidis.

Acetyl-CoA hydrolase belongs to a large family of thioesterase enzymes which catalyse the hydrolysis of thioester bonds linking coenzyme A to fatty acids. Thioesterases are split into two major superfamilies: α/β-hydrolases and hotdog-fold thioesterases depending on structural folds and the catalytic reaction mechanism (Hunt & Alexson, 2002 ▶). The function of acetyl-CoA hydrolase in fatty-acid metabolism is well understood; however, their cellular roles in regulating the concentrations of CoA and various other fatty acyl-CoA molecules remain to be fully elucidated. They have been implicated in a range of cellular processes including gene regulation, signal transduction, membrane synthesis and inflammation in humans (Kirkby et al., 2010 ▶). The structural and biochemical characterization of this acetyl-CoA hydrolase from N. meningitidis will assist in understanding their roles in many cellular processes and specifically in this pathogenic bacterium.

2. Methods

2.1. PCR and cloning

The gene encoding the acetyl-CoA hydrolase from N. meninigitidis FAM18 was amplified by PCR using the forward and reverse primers TACTTCCAATCCAATGCC ATGACACAACAACGCCAACTGC and TTATCCACTTCCAATGTTA TCAGCAGCCGCAGGACATG, respectively, where the nucleotides in bold are complementary to the gene sequence and the underlined nucleotides are required for the ligation-independent cloning (LIC) procedure. The amplified gene was purified using a Qiagen PCR purification kit and cloned into SspI-digested and linearized pMCSG21 vector following T4 polymerase treatment (Eschenfeldt et al., 2009 ▶). Clones were initially confirmed by colony PCR and the fidelity to the sequence was confirmed by DNA sequencing at the Australian Genome Research Facility.

2.2. Protein expression and purification

Recombinant protein was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS cells as an N-terminally His6-tagged fusion protein. A single colony of transformed E. coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS cells was grown in 5 ml Luria Bertani (LB) broth overnight and 1 ml of this primary culture was added to 500 ml of auto-induction medium (Studier, 2005 ▶) containing 100 µg ml−1 spectinomycin and incubated in a shaker incubator at 298 K for 24 h. Following centrifugation, the cell pellet was resuspended in His buffer A (50 mM phosphate buffer pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole) in 1/10 of the volume and frozen at 253 K. Cell lysis was performed by three freeze–thaw cycles and the addition of lysozyme (1 ml of 20 mg ml−1 stock). Following centrifugation, the cleared supernatant was applied onto a 5 ml His column (HisTrap HP, GE Healthcare) using FPLC, washed in buffer A and eluted with buffer B (50 mM phosphate buffer pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole) using a gradient to 100% buffer B. His-tag removal was performed by TEV protease treatment, leaving three extra N-terminal amino acids (Ser, Asp and Ala). Size-exclusion chromatography (Hiload 26/60 Superdex 200 column, GE Healthcare) was performed to remove minor impurities and aggregates and to exchange the buffer to 50 mM Tris, 125 mM NaCl pH 8.0. The protein was concentrated to 25 mg ml−1, aliquoted and stored at 193 K.

2.3. Crystallization

Sparse-matrix screening was performed by the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method in 48-well plates using a 1:1 ratio of protein solution and crystallization screen solution (Hampton Research). Plates were observed at 24 h intervals. Crystal optimizations of positive conditions were performed by varying the pH and the concentrations of precipitant and protein.

2.4. X-ray diffraction and structure solution

Diffraction data were obtained from the optimized crystals at the Australian Synchrotron. The collected X-ray diffraction data were auto-indexed, merged and scaled using iMosflm (Battye et al., 2011 ▶). Phases were determined by molecular replacement using Bacillus halodurans (PDB entry 1vpm; 33% identity; Joint Center for Structural Genomics, unpublished work) as a search model. Model building and refinement produced a model with an R and R free of 0.167 and 0.194, respectively, and the model has been deposited in the PDB (PDB entry 4ien; Y. B. Khandokar & J. K. Forwood, unpublished work). Full structural and functional analysis including mutagenesis is currently being undertaken.

3. Results

3.1. Expression and purification

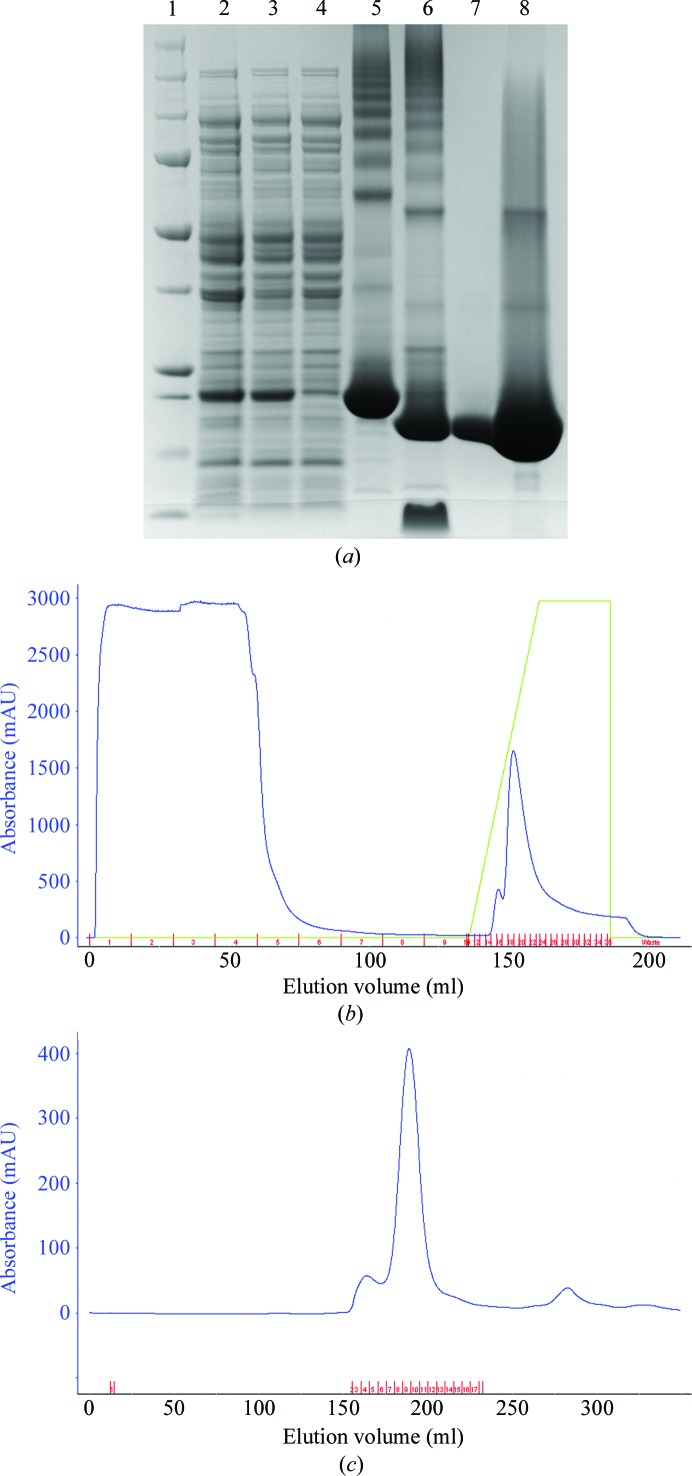

The recombinant acetyl-CoA hydrolase from N. meningitidis FAM18 (NmACH) was overexpressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS cells using auto-induction, producing approximately 30 mg of protein per litre of culture. The protein was highly soluble (Fig. 1 ▶ a, lanes 2 and 3), and purification by His6 affinity chromatography resulted in approximately 95% purity and the recovery of approximately 25 mg of protein (Figs. 1 ▶ b and 1 ▶ c). Removal of the His6 tag by TEV treatment resulted in a reduction in molecular weight of NmACH of 3 kDa, consistent with the size of the affinity tag. Size-exclusion chromatography increased the purity and the homogeneity of NmACH required for crystallization, as confirmed by the single elution peak in size-exclusion chromatography (Fig. 1 ▶ c) and SDS–PAGE analysis (Fig. 1 ▶ a). Thioesterase activity was confirmed against the acetyl-CoA substrate (to be published, data not shown).

Figure 1.

Purification of NmACH. (a) SDS–PAGE was performed to assess the solubility and homogeneity of the protein. The protein is present in both the whole cell and the soluble fraction (lanes 2 and 3, respectively). (b) Affinity column elution profile showing unbound proteins (lane 4) and NmACH elution (lane 5) at approximately 250 mM imidazole and subsequent 3 kDa His-tag removal by TEV protease treatment (lane 6). (c) Size-exclusion chromatogram representing a singular symmetrical peak indicative of a highly pure and homogeneous protein (lane 7) and concentrated protein (lane 8).

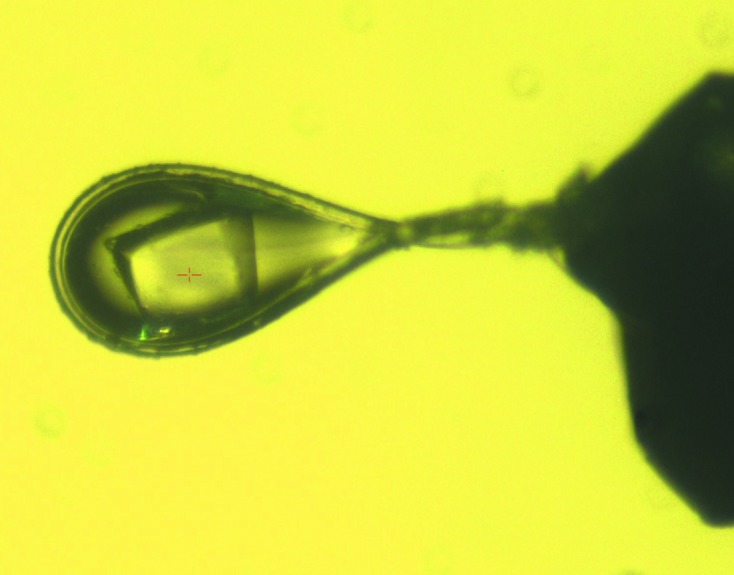

Figure 2.

An NmACH protein crystal mounted in a loop during X-ray diffraction data collection.

3.2. Crystallization and diffraction

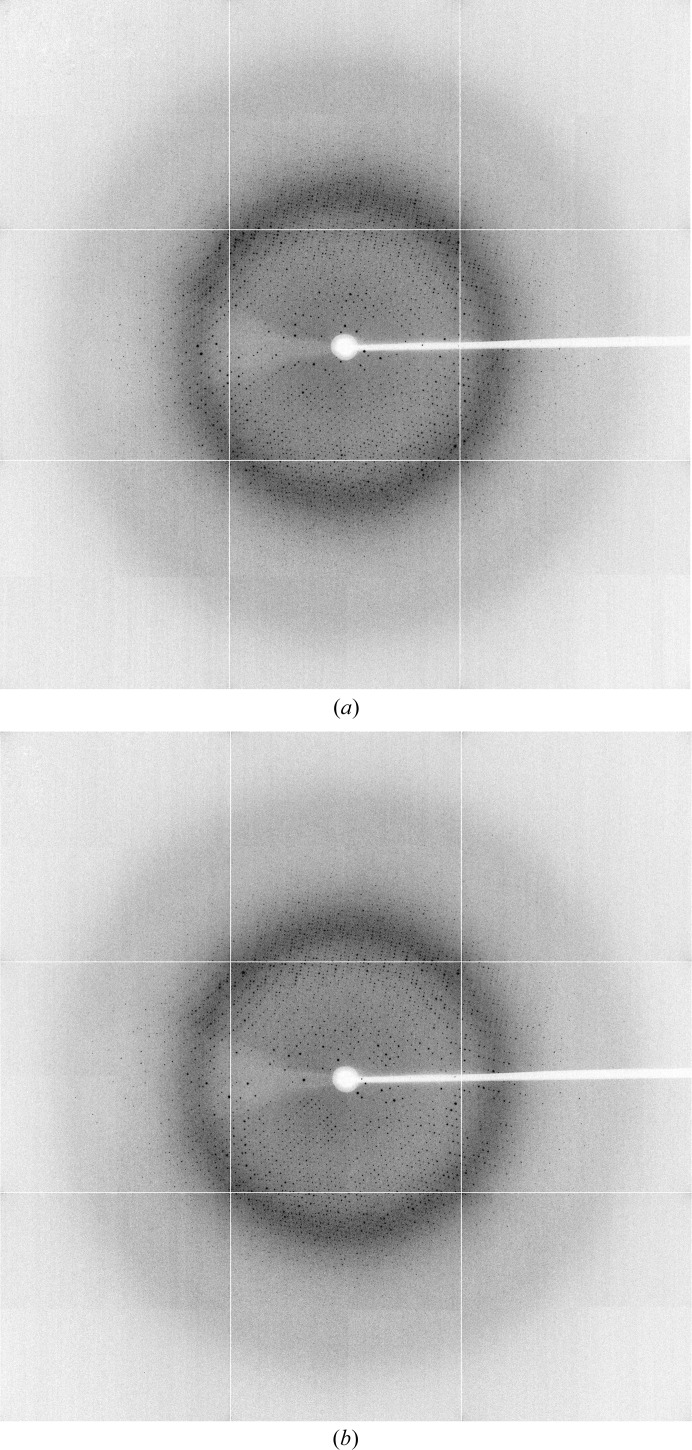

Conditions that induced crystallization of NmACH were determined through sparse-matrix screening using the commercially available Crystal Screen and PEG/Ion from Hampton Research. From these screens, six conditions produced crystals (Crystal Screen condition Nos. 3, 11, 32, 37, 47 and 48), which were based on ammonium phosphate and ammonium sulfate. All conditions were optimized by varying the pH and precipitant concentration to produce diffraction-quality crystals. Optimization of the pH of the Tris buffer (7.5, 8.0 and 8.5) and the concentration of ammonium phosphate (0.4–2 M) produced large, single and diffraction-quality crystals (Fig. 2 ▶). A final cryoprotection condition including 30% glycerol with 100 mM Tris pH 8.5 and 2 M ammonium phosphate was used to freeze the crystals, which were then carried to the Australian Synchrotron. These crystals were very stable and resistant to synchrotron-radiation damage throughout 360° of data-collection rotation and produced good-quality diffraction data (Fig. 3 ▶). The crystals belonged to space group P213 with unit-cell parameter 152.52 Å and data frames were integrated and scaled to 2 Å resolution using iMosflm v.1.0.5 with R p.i.m. values of 0.029 and 0.135 across all resolution shells and in the outer resolution shell, respectively. The data-collection statistics are summarized in Table 1 ▶. The data did not appear to be twinned as determined using POINTLESS from the CCP4 suite (Winn et al., 2011 ▶) to calculate the minimal twinning probability, and the Matthews coefficient (Matthews, 1968 ▶) suggested that four molecules were present in the asymmetric unit. The structure was solved by molecular replacement using PDB entry 1vpm as a search model, with 33% amino-acid identity to NmACH. The PDB file and structure factors of NmACH including coenzyme A ligand and GDP cofactor have been validated and deposited in the PDB and assigned PDB code 4ien. Full structural and functional analysis including activity and specificity assays, mutagenesis and crystallization with different ligands is currently being undertaken.

Figure 3.

X-ray diffraction patterns at (a) 1° and (b) 360°.

Table 1. Data-collection statistics.

Values in parentheses are for the outermost resolution shell.

| Crystal system | Cubic |

| Space group | P213 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 35.95–2.00 (2.11–2.00) |

| No. of measured reflections | 3456188 (493262) |

| No. of unique reflections | 79721 (11597) |

| Completeness (%) | 100 |

| Multiplicity | 43.4 (42.5) |

| Mosaicity (°) | 0.12 |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 17.9 (4.1) |

| R p.i.m. | 0.029 (0.135) |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 29.5 |

Acknowledgments

We thank the beamline scientists and acknowledge use of the Australian Synchrotron. JKF is an Australian Research Council (ARC) Future Fellow. Funding has been provided by the Australian government and the School of Biomedical Sciences, Charles Sturt University.

References

- Battye, T. G. G., Kontogiannis, L., Johnson, O., Powell, H. R. & Leslie, A. G. W. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cohn, A. & Jackson, M. L. (2012). CDC Health Information for International Travel, edited by G. W. Brunette, pp. 250–253. Oxford University Press. http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2012/chapter-3-infectious-diseases-related-to-travel/meningococcal-disease.htm

- Eschenfeldt, W. H., Lucy, S., Millard, C. S., Joachimiak, A. & Mark, I. D. (2009). Methods Mol. Biol. 498, 105–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hunt, M. C. & Alexson, S. E. (2002). Prog. Lipid Res. 41, 99–130. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kirkby, B., Roman, N., Kobe, B., Kellie, S. & Forwood, J. K. (2010). Prog. Lipid Res. 49, 366–377. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Matthews, B. W. (1968). J. Mol. Biol. 33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Molesworth, A. M., Cuevas, L. E., Connor, S. J., Morse, A. P. & Thomson, M. C. (2003). Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9, 1287–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Studier, F. W. (2005). Protein Expr. Purif. 41, 207–234. [DOI] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Initiative for Vaccine Research (2013). Bacterial Infections: Meningococcal Disease http://www.who.int/vaccine_research/diseases/soa_bacterial/en/index1.html.

- Winn, M. D. et al. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 235–242.