Abstract

Leptin is commonly thought to play a detrimental role in exacerbating experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) and multiple sclerosis. Paradoxically, we show here that astrocytic leptin signaling has beneficial effects in reducing disease severity. In the astrocyte specific leptin receptor knockout (ALKO) mouse in which leptin signaling is absent in astrocytes, there were higher EAE scores (more locomotor deficits) than in the wildtype counterparts. The difference mainly occurred at a late stage of EAE when wildtype mice showed signs of recovery whereas ALKO mice continued to deteriorate. The more severe symptoms in ALKO mice coincided with more infiltrating cells in the spinal cord and perivascular brain parenchyma, more demyelination, more infiltrating CD4 cells, and a lower percent of neutrophils in the spinal cord 28 days after EAE induction. Cultured astrocytes from wildtype mice showed increased adenosine release in response to interleukin-6 and the hippocampus of wildtype mice had increased adenosine production 28 days after EAE induction, but the ALKO mutation abolished the increase in both conditions. This indicates a role of astrocytic leptin in normal gliotransmitter release and astrocyte functions. The worsening of EAE in the ALKO mice in the late stage suggests that astrocytic leptin signaling helps to clear infiltrating leukocytes and reduce autoimmune destruction of the CNS.

Keywords: EAE, Reactive astrogliosis, Leptin receptor, Neuroinflammation, Autoimmunity, Adenosine

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is associated with elevated serum leptin concentrations (Frisullo et al., 2007), and resolution of MS symptoms correlates with a decrease of serum leptin (Angelucci et al., 2005; Batocchi et al., 2003). In a commonly used mouse model of MS, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), leptin appears to play a deleterious role in conferring disease susceptibility after peripheral delivery (Matarese et al., 2001), and use of blocking antibodies or soluble leptin receptor benefits EAE (De Rosa et al., 2006; Matarese et al., 2005).

There are situations, however, in which a polypeptide plays opposite roles in the CNS and periphery, with cell type specific actions (Banks and Kastin, 1993; Kastin and Pan, 2010; Pan et al., 2012b). Once produced by fat cells and released into the circulation, leptin can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) by receptor-mediated transport (Banks et al., 1996; Pan and Kastin, 2007). In EAE, not only is BBB permeability increased in general (Juhler et al., 1984; Pan et al., 1996), but leptin transport is increased selectively (Hsuchou et al., 2013). In the CNS, leptin may act on either neurons or glial cells, and astrocytic signaling may differ from neuronal signaling as has been suggested in several models. While leptin provides neuroprotection (Farr et al., 2006; Garza et al., 2008; Tang, 2008), inhibition of astrocytic activity accentuates neuronal leptin signaling, indicating antagonistic roles of astrocytes and neurons in leptin processing (Pan et al., 2011). Astrocyte-specific leptin receptor knockout (ALKO) mice with a mutant membrane-bound leptin receptor lacking signaling function (Hsuchou et al., 2011) show more resistance to seizure induction (Jayaram et al., 2013a). This is opposite from the alleviation of seizure severity after leptin treatment by intranasal delivery (Xu et al., 2008), and is more consistent with a proconvulsive role of leptin after intracerebroventricular delivery (Ayyildiz et al., 2006). The results suggest that astrocytic leptin signaling may play counter-regulatory roles with an effect opposite from that seen after systemic delivery of leptin.

Having shown that the astrocytic leptin receptor (ObR) is upregulated in EAE mice (Wu et al., 2013), we hypothesized that leptin enhances astrocytic leptin signaling to modulate the recovery of mice from EAE. This predicted beneficial effect of astrocytic leptin signaling is supported by findings from a few analogous models. A crucial role of astrocytic gp130 signaling in ameliorating EAE has been shown. Astrocytes in the GFAP-Cre gp130(fl/fl) mice are apoptotic, rather than developing reactive gliosis as in WT mice. These astrocytic gp130 knockout mice have more demyelination and CD4+ T cell infiltration, as well as changed T cell subtype composition (Haroon et al., 2011). The results indicate a protective effect of astrocytic gp130 signaling against EAE. Similarly, mutant mice with astrocytic expression of dominant negative interferon (IFN)-γ receptor show more sustained inflammation and clinical symptoms, and greater demyelination (Hindinger et al., 2012). Thus, astrocytic IFNγ signaling facilitates recovery of mice from EAE, not supporting a biphasic role of IFNγ with early exacerbation of the disease (Kelchtermans et al., 2008). Overall, an understanding of how astrocytic leptin signaling modulates EAE may provide mechanistic insight into how astrocytic functions are modulated by blood-borne cytokines and in turn affect cell-cell interactions essential to curtail CNS autoimmune disorders.

Materials and Methods

Mice and EAE induction

The animal protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. To determine the relationship between astrocytic ObR and EAE severity, we used ALKO mice lacking a signaling astrocytic ObR that were generated in our laboratory (Hsuchou et al., 2011). The ALKO mice were produced by the crossing of GFAP-cre mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) with ObR-floxed mice obtained from Dr. Streamson S. Chua Jr (McMinn et al. 2004, 2005). Both strains were on an FVB background. The F1 generation of GFAPcre/wt ObRloxP/- mice were backcrossed with ObR-floxed homozygote mice to generate F2 mice, about one-fourth of them being ALKO as verified by tail genotyping. Since the two loxP sites flank exon 17 of ObR encoding the cytoplasmic domain, the resulting mutant receptor (A17) remains membrane-bound without signaling function, as it lacks Box1 (shared by ObRa, ObRb, and ObRc), Box2, and Box3 (unique to ObRb) in the cytoplasmic domain. In ALKO mice, tail genotyping PCR products contain GFAP-cre, Δ17 sequence, and floxed ObR. The littermate controls do not have GFAP-cre but rather the wildtype (WT) allele, although they also contain the floxed ObR sequence. The ObR-floxed mice have been shown to be phenotypically identical to WT mice (McMinn et al, 2004, 2005), and are termed WT in this study.

Weaning and genotyping were performed when the mice were 21 days old. Mice were randomly housed, ALKO mice being maintained in the same cages as WT mice. The F9 generation of mice from our breeding colony was used for these studies. Since a small number of neural progenitor cells along the ventricles also can be GFAP (+) (Casper et al., 2007), GFAP-cre mediated mutation of ObR may cause a mild reduction in the pool of neuronal leptin signaling.

EAE was induced in 8–10 week old female ALKO and littermate controls following an established protocol (Li et al., 2011). Each mouse received subcutaneous injection of 100 µg of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) fragment 79–96 (MOG79–96) emulsified in 100 µl of complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) containing 500 µg of heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37RA (DIFCO Laboratories, Detroit, MI). Pertussis toxin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was injected intraperitoneally immediately after induction and again 48 h later. The time of induction is considered EAE day 0. Symptoms were monitored daily by use of a standard EAE score sheet (Pan et al., 1996; Wu et al., 2010, 2013), with 0 being symptom-free and 5 being the worst (moribund or dead).

Leukocyte isolation and flow cytometry

To determine how ALKO affects immune profiles under basal conditions, 19 and 28 days after EAE induction leukocytes were isolated from whole spinal cord following an established protocol (Pino and Cardona, 2011). Mice were anesthetized and perfused intracardially with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to remove leukocytes remaining in the spinal cord vasculature. The spinal cord was dissected and homogenized in PBS supplemented with 0.1% fetal calf serum. The homogenate was brought with 100 % isotonic Percoll (Sigma-Aldrich) to a 30 % Percoll solution, layered on top of a 70 % isotonic Percoll solution in a 15 ml polypropylene conical tube, and centrifuged at 500 g for 30 min. Cells residing at the 30:70 % interphase were collected, washed with PBS, and used for flow cytometry analysis.

Splenocytes were subjected to analysis simultaneously. To prepare splenocytes from WT and ALKO mice, spleens in PBS were ruptured with the inlet of a 3 ml syringe. The homogenate was filtered through a 40 µm nylon mesh, and the flow-through was centrifuged at 387 g for 10 min. The pelleted cells were resuspended in red blood cell lysis buffer (1 ml /spleen) (R7757, Sigma). Cells were washed with FACS buffer twice, immunostained, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA), and stored in PBS until flow cytometry analysis.

For cell surface staining of immune markers, the cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated CD4 (Clone GK1.5, catalog number 100405), PE anti-mouse CD8a (Clone 53–6.7, catalog number 100707) Alexa488-conjugated CD11b (Clone M1/70, catalog number 101219), and APC-conjugated GR1 antibodies (Clone RB6–8C5, catalog number 108411) (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) for single color staining. Non-stained cells were used as negative controls. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry analysis on a FACSCalibur (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Data were analyzed with post-collection compensation by FlowJo (Tree Star, Ashland, OR) software.

Antigen recall assay

Splenocytes from WT or ALKO mice at day 27 after EAE induction were isolated as described above and seeded to 96-well plates (n = 2 mice /group, with triplicated wells for each mouse) at a density of 0.5×106 cells/well in complete RPMI-10 medium. Immediately after plating, the cells were treated with 15 µl of PBS only (control), MOG79–96 (30 µg/ml), or another heptagon proteolipid protein (PLP)139–151 (30 µg/ml). At 72 h of culture in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C, the cells designated for CD4 staining were incubated with a FITC-conjugated CD4 antibody and processed for cell-surface staining and flow cytometry. The cells designated to determine T helper cell (Th) subtypes were fixed with 1 ml/tube Fix/Perm solution (catalog number 421403, BioLegend) in the dark for 20 minutes at room temperature, washed by staining buffer and perm buffer, and incubated with perm buffer for 15 minutes in dark. Cells were centrifuged and resuspended in 50 µl of perm buffer with antibodies for either PE anti-mouse IFN-γ antibody (Clone XMG1.2, catalog number 505807, BioLegend) or APC anti-mouse IL-17A antibody (Clone TC11–18H10.1, catalog number 506915, BioLegend) for 30 min on water ice bath. The cells were then thoroughly washed with PBS and processed for flow cytometry.

Tissue morphology and inflammatory cell infiltration

On day 28 after EAE induction by MOG79–96, anesthesized ALKO and WT mice were sacrificed. Spinal cord tissues were removed, embedded in Histo-prep™ medium (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), and snap frozen. Serial sections of 15 µm thickness were obtained with a Leica CM 1950 cryostat and thaw-mounted on superfrost plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). One of every five sections from the cervical region was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) to determine the pattern and extent of cellular infiltration.

To determine the extent of demyelination by Luxol Fast Blue (LFB, Polysciences, Warrington, PA) stain, we mounted spinal cord and brain coronal sections on slides. After treatment with 1:1 alcohol/chloroform and 95% ethanol, the tissue was stained with preheated LFB at 56 °C overnight. Slides were then cleared with 95% ethanol and distilled water, differentiated with 0.05 % lithium carbonate followed by 70% ethanol, rinsed in deionized water, and counterstained with cresyl violet solution (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 30–40 seconds, rehydrated with ethanol, cleared in xylene, and cover slipped with synthetic resin. Images of sections stained with HE or LFB were acquired by use of the Hamamatsu NanoZoomer Digital Slide Scanning System equipped with a NanoZoomer Viewer Software (Hamamatsu, Japan).

Measurement of adenosine concentration

To determine the effect of ALKO mutation and cytokines on adenosine release in cultured astrocytes, primary astrocytes were obtained from the WT and ALKO neonates within a week of birth, as described previously (Hsuchou et al., 2009a, 2012). The cells were grown to full confluency after 10 days in culture on poly-D-lysine coated 24-well plates. Serum was withdrawn from the cell culture medium for 6 h. The astrocytes were then treated with leptin (100 ng/ml) or IL6 (10 ng/ml) for 30 min, and compared with a control group with DMEM medium only (n = 3 /group). The cell culture medium was collected for measurement of adenosine release by mass spectrometry through a contractual service with Drumetix Laboratories (Greensboro, NC). The concentrations of adenosine to generate the linear standard curve were 52, 134, 531, 508, and 1270 nM (r = 0.97), with dilution factors of 0.005, 0.02, 0.02, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, and 1 from the highest concentration. Triplicated wells were used for each group, and each sample was analyzed in duplicate to obtain a mean value for the well. The concentration of adenosine in each well was normalized to protein concentration of the lysed astrocytes by use of a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

To determine how ALKO mutation and EAE disease course affect adenosine release in-vivo, ALKO and WT mice on day 28 after EAE induction were used for dissection of hippocampus and hypothalamus on ice immediately after decapitation. Naïve mice and those 28 days after CFA injection (adjuvant control for EAE) were also studied simultaneously (n = 3 /group for 6 groups). The freshly isolated tissue was weighed, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, stored at −80 oC, and shipped on dry ice (−20 °C) to the mass spectrometry facility at Drumetix for further processing on dry ice and mass spectrometry measurement. The concentration of adenosine was expressed as µmol/g of tissue.

Statistical analysis

All the data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean. In the studies to determine the effects of ALKO genetic mutation on EAE scores, repeated measures 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed, followed by Bonferoni’s post-hoc test to determine the difference among groups on individual days. In the analysis of EAE incidence, the Mantel-Cox Log-rank test was performed. The differences in the percent of the type of infiltrating leukocytes measured by flow cytometry were determined by 2-way ANOVA for the effects of strain (WT vs ALKO) and days after EAE induction. The difference in cell proliferation of splenocytes after antigen recall, and adenosine release by cultured astrocytes or from hippocampus and hypothalamus of mice were also determined by 2-way ANOVA for the effects of strain and treatment, followed by Bonferoni’s post-hoc analyses.

Results

1. ALKO mice show higher EAE scores

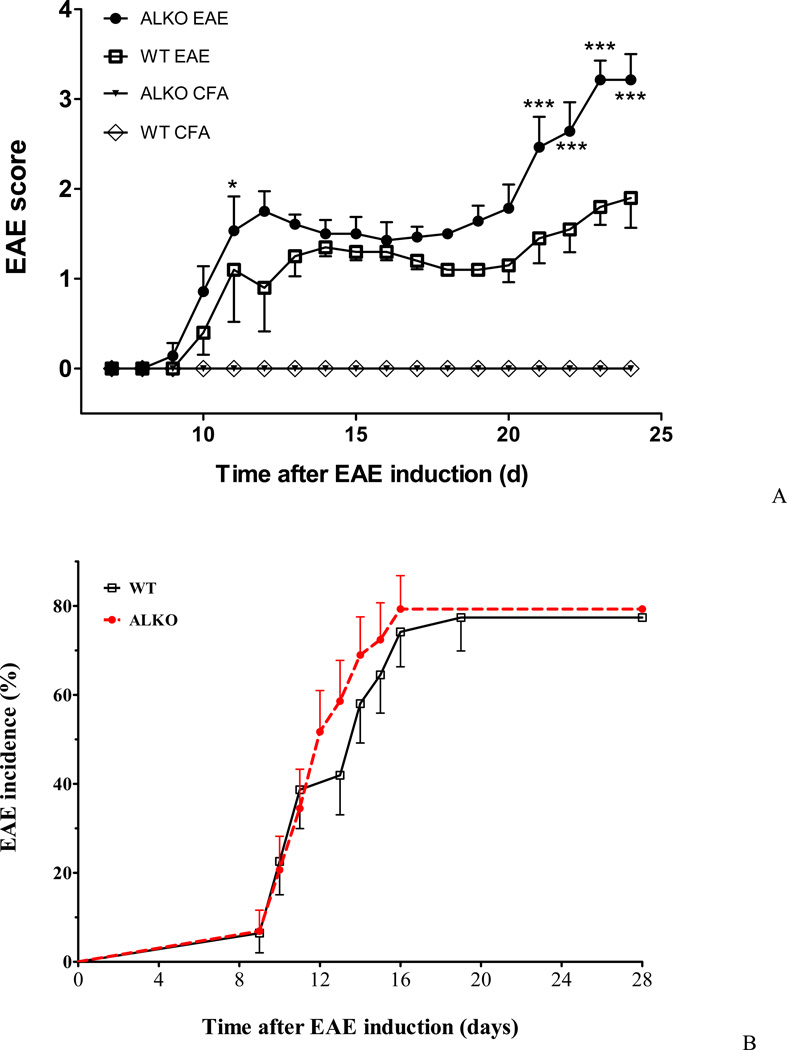

Four groups of mice were studied simultaneously, and the results were replicated 3 times. The groups were: WT mice with EAE; WT mice with CFA adjuvant only without the specific haptogen MOG79–96; ALKO mice with EAE; and ALKO mice with CFA only (n = 5–7 /group). None of the CFA control mice developed EAE scores of more than 0.5 on any day. All EAE mice had apparent weakness by day 10 that persisted until the end of the study on day 28. The locomotor deficit had an ascending pattern, starting from the tail and hindlimbs. Repeated measures 2-way ANOVA showed significant effects of both time and EAE, as well as significant interactions of these factors. When only WT EAE and ALKO were compared, there was a significant effect of strain (F1,170 = 16.7, p < 0.005), and of time (F17,170 = 22.7, p < 0.0001). The interaction of these two factors was also significant. The ALKO EAE group (n = 7) had a significant increase of scores on day 10 in comparison with the CFA treated controls, and this persisted throughout the rest of the study. The WT EAE group (n = 5) showed a significant increase on day 11 that also persisted till day 25. Post-hoc analysis showed that the scores in the ALKO EAE group was higher than WT EAE on day 11, day 21, day 22, day 23, and day 24 (Fig.1A). All were higher than for the CFA groups.

Fig. 1. EAE severity and disease incidence in WT and ALKO mice.

(A) ALKO mice had a significantly higher EAE score than WT mice after induction by MOG79–96 along with CFA and pertussis toxin, whereas adjuvant-only controls did not show clear symptoms. Differences on individual days determined by post-hoc analysis are shown by *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.005 for differences between ALKO EAE and WT EAE. (B) There was no significant difference in EAE incidence between WT EAE and ALKO EAE groups.

The results showed that the difference mainly occurred at the time when WT mice started to stabilize and some show signs of recovery. Rather than entering the recovery stage, however, the ALKO mice continued to deteriorate in locomotor function, mobility, urinary control, and body weight, with persistently high EAE scores. Disease incidence was determined by the Mantel-Cox Log-rank test, and it showed that the overall onset and prevalence of EAE did not differ significantly between the WT and ALKO mice (Fig. 1B). Thus, although the induction rate of EAE did not change as a result of the ALKO mutation, the recovery of mice was significantly hampered as shown by persistently high scores in the ALKO group while the WT mice were in the late phase of EAE.

2. ALKO mice show altered temporal pattern and composition of leukocyte infiltration after EAE, particularly on day 28 when WT mice had some recovery

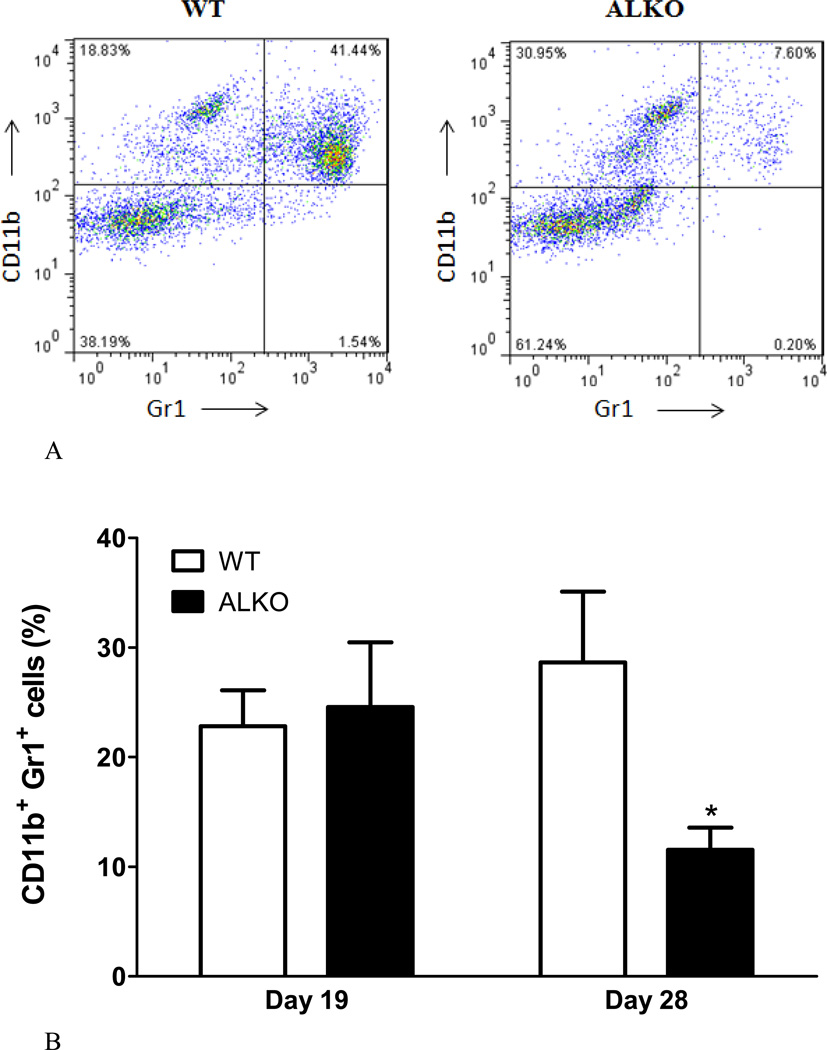

Four groups of mice were studied: WT at day 19 of EAE; WT day 28 of EAE; ALKO day 19 of EAE; and ALKO day 28 of EAE (n = 7 /group). The infiltrating cells were recovered from the spinal cord of each group for flow cytometry analysis of the percent of CD4, CD11b, and GR1-immunopositive cells. The time points of day 19 and day 28 were selected because they represent times when the two groups of mice had similar and different scores, respectively. When each subset of leukocytes was analyzed by 2-way ANOVA to determine the effects of strain and time after EAE, there was no significant overall effect on each of the subpopulations, and there was no significant interaction. However, the ALKO mice had fewer CD11b+ GR1+ myeloid cells (neutrophils) and more CD4+ T cells in the spinal cord than WT mice on day 28. The representative 2-D dot plot with gating for Alexa488-CD11b and APC-Gr1 is shown as figure 2A. There was a significant reduction of these neutrophils seen at the upper right quadrant for the ALKO mice in comparison with the WT controls on day 28 (p < 0.05, Fig.2B). On the contrary, there was an increase of CD4+ T cells on day 28 (p < 0.05, Fig.2C). There was no difference for either subpopulation on day 19. The CD11b+GR1- monocytes also did not show a significant difference between the two groups on either day.

Fig. 2. Population of infiltrating cells in the spinal cord of WT and ALKO mice.

(A) A representative 2-D dot plot of gated Alexa488-CD11b and APC-Gr1 stained myeloid cells. (B) On day 19 after EAE induction, there was no difference in the percent of CD1 1b+ and GR1+ neutrophils between the WT and ALKO mice (n = 3–4 /group). On day 28, there was a reduction CD1 1b+Gr1+ neutrophils in the ALKO mice in comparison with the WT group (n = 7 /group). (C) The CD4+ T cells showed no difference on day 19 but were increased in the ALKO mice compared with WT mice on day 28. *: p < 0.05 when ALKO was compared with WT on day 28.

3. Changes of peripheral leukocyte profiles and antigen recall

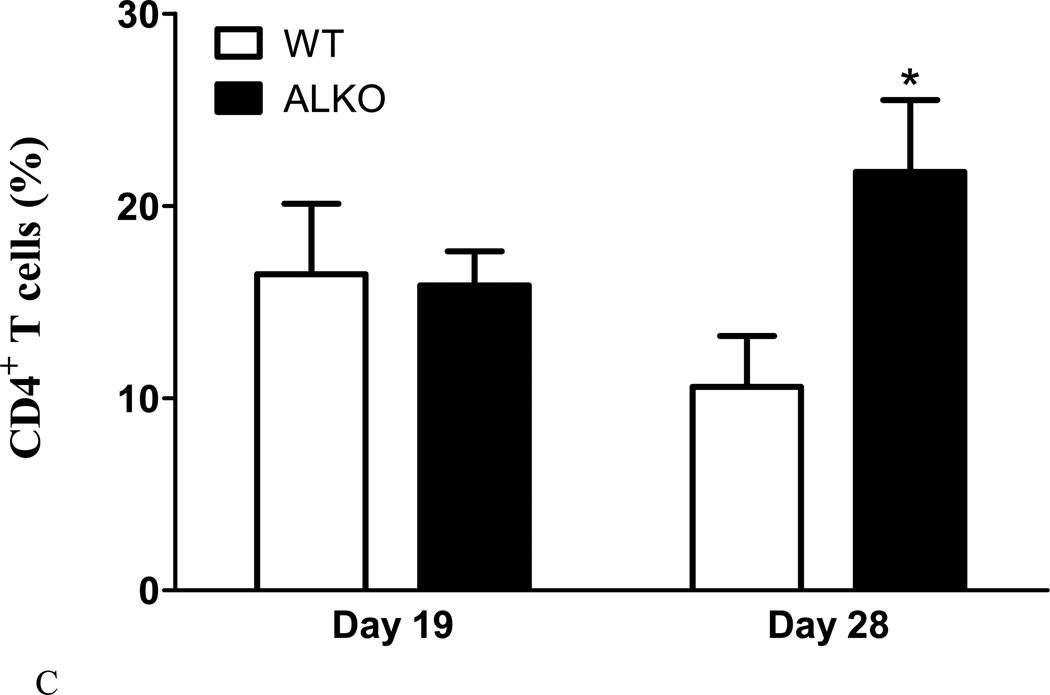

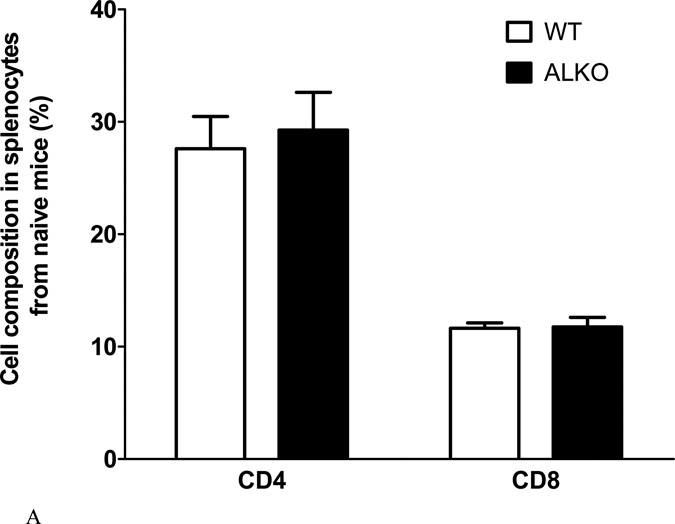

The lack of change in the composition of infiltrating leukocytes on day 19 after EAE induction suggests that peripheral leukocyte activation did not differ between the ALKO and WT mice at this time. Consistently, splenocytes isolated from naïve mice also showed the same percent of CD4 and CD8 T cells between the ALKO and WT groups (Fig.3A).

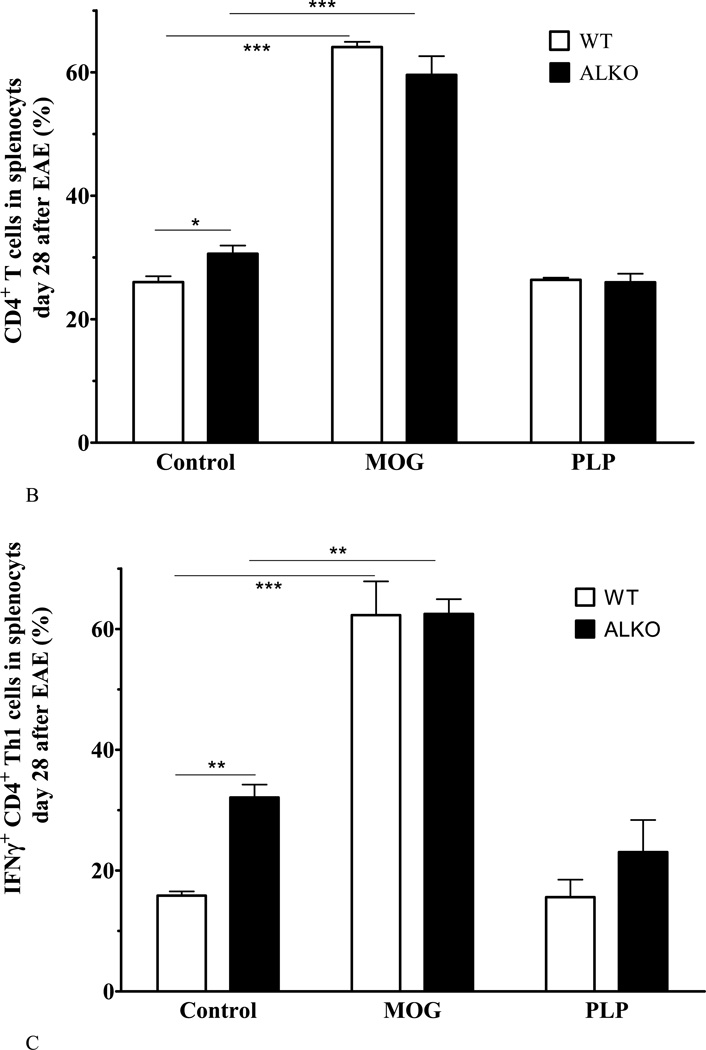

Fig. 3. Effect of ALKO on splenocytes from naïve or EAE mice 28 days after induction.

(A) In naïve mice, the percent of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells did not differ between WT and ALKO mice (n = 3 /group). (B) Splenocytes isolated from mice on day 28 after EAE induction showed an increase in proliferation of CD4+ T cells from ALKO mice in comparison with those from WT mice. Both responded to MOG79–96 with a significant increase of proliferation but there was no change after PLP139–151 (n = 3/group). (C) Among these CD4+ cells, Th1 proliferation was higher in ALKO splenocytes in the basal condition and there was a similar extent of increase after MOG79–96. (D) Among these CD4+ cells, Th17 proliferation was also higher in ALKO splenocytes; MOG79–96 challenge induced a further increase only in WT mice whereas PLP139–151 challenge had no effect. *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.005.

However, antigen recall assay of splenocytes isolated from mice 28 days after EAE induction showed an overall difference in strain and stimuli. In the absence of stimulation, the splenocytes from the ALKO EAE and WT EAE mice had similar levels of proliferation. The ALKO EAE splenocytes had a higher percent of CD4+ cells than the WT (Fig.3B). Among these CD4+ cells, there was also a higher percent of Th1 cells (IFNγ+) (Fig.3C) as well as Th17 (IL17+) cells (Fig.3D). The results are consistent with persistent immune activation in ALKO mice in comparison with WT mice that had already entered the recovery stage. Ex-vivo MOG79–96 incubation increased the percent of CD4+ cells and CD4+IFNγ+ Th1 cells in both WT and MOG mice, indicating successful antigen recall. However, PLP139–151 did not induce splenocyte proliferation in the splenocytes from mice challenged with MOG79–96 for EAE induction. This indicates antigen specificity without clear epitope spreading in the splenocytes from these mice. The proliferation of Th1 cells in the ALKO mice in response to MOG79–96 (Fig.3C) was in contrast to the lack of significant increase of Th17 cells from these mice, and it appears to result from their high basal proliferation in the absence of antigen recall (Fig.3D).

4. ALKO mice show greater cell infiltration and tissue damage

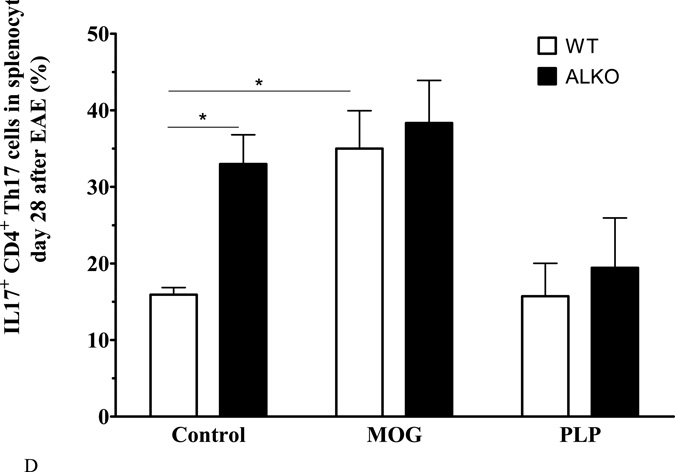

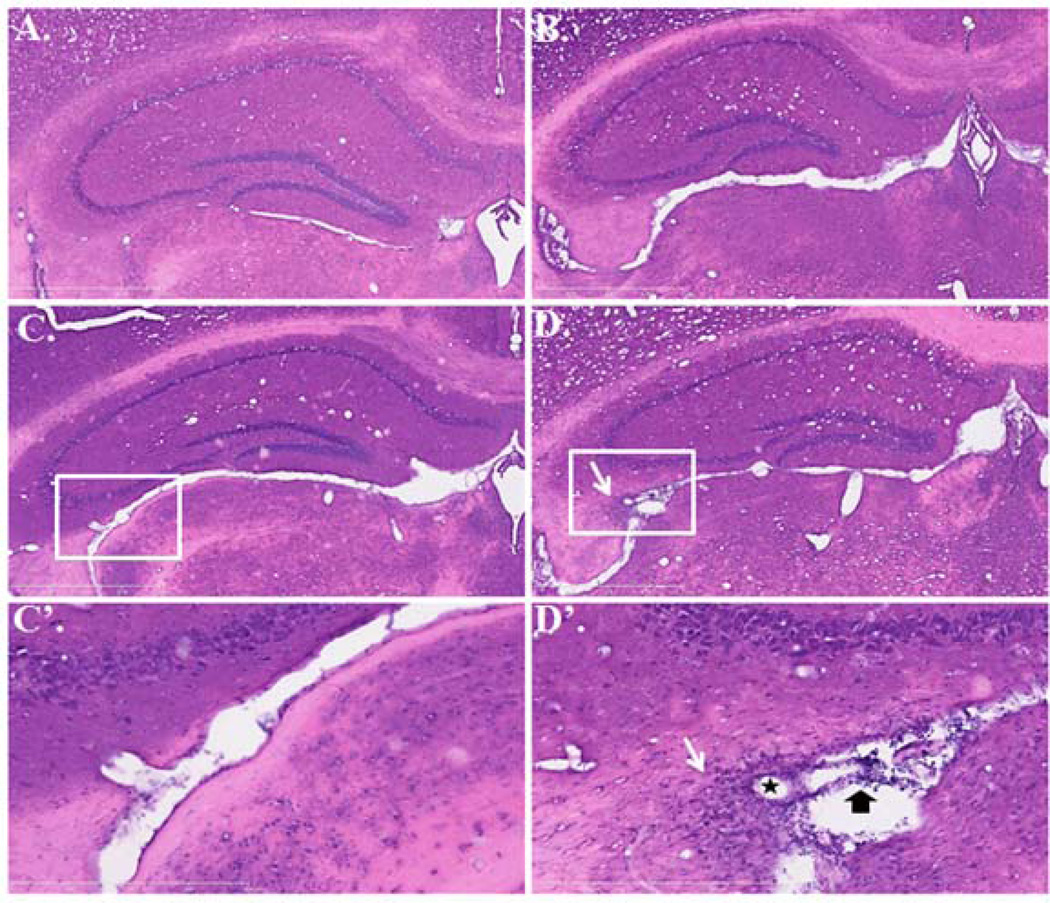

Two groups of mice were studied: WT and ALKO mice 28 days after EAE induction. Cross sections of cervical spinal cord were examined with HE and LFB myelin staining for changes in cytoarchitecture and inflammatory cell infiltration. Cervical spinal cord was chosen because it shows the most lesions in EAE (Lanens et al., 1994). In WT mice 28 days after EAE, HE staining showed leukocyte infiltration localized in the meninges (Fig.4A, C and E). In ALKO mice, the infiltration was seen not only in the meninges (Fig.4B, D, and F) but also disseminated in parenchymal tissue (Fig.4F).

Fig. 4. HE staining of cervical spinal cord 28 days after EAE induction.

In a WT mouse (A, C, and E), there was a moderate increase of perivascular cuffing and higher cellularity along the dorsal spinal artery. In an ALKO mouse (B, D, and F), there was more perivascular cuffing around the dorsal spinal artery and cellular infiltration in the adjacent spinal cord parenchyma. The higher magnification images of the WT (E) and ALKO (F) mice show that the latter had an increased number of infiltrating cells in the dorsolateral region of the cervical spinal cord. Scale bar: 400 µm.

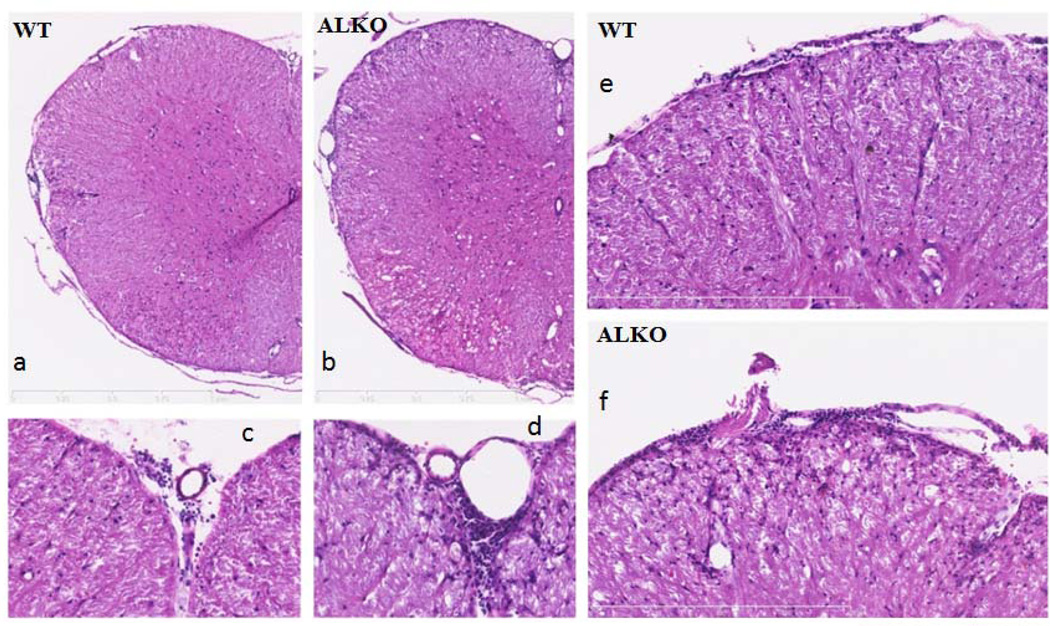

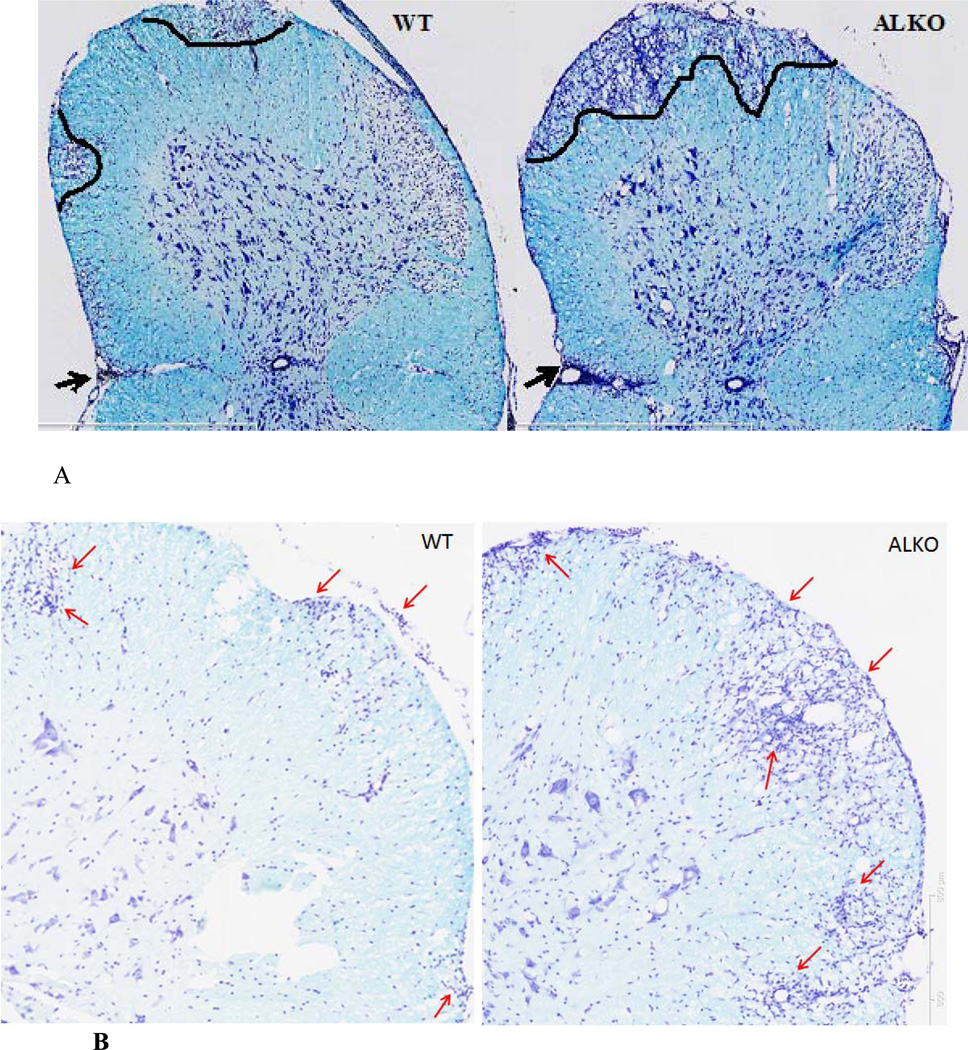

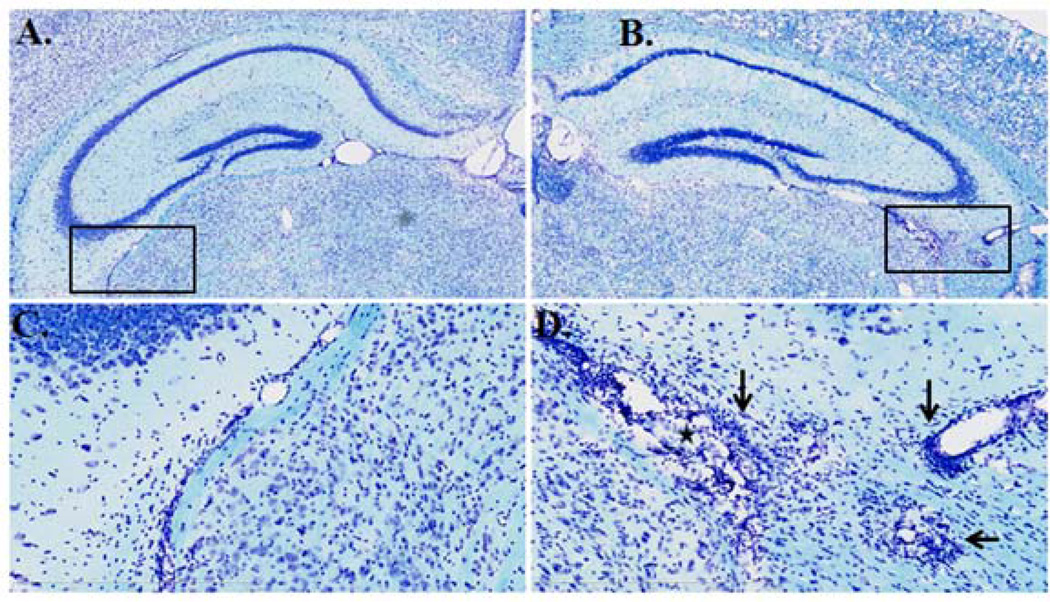

LFB staining shows the pattern of myelination and the counterstain indicates the extent of cellular infiltration. In the cervical spinal cord of WT mice 28 days after EAE, demyelination was seen as patchy areas of loss of LFB staining. In the demyelinated regions and perivascular space, there was inflammatory cell infiltration shown by cresyl violet counterstaining, similar to that seen with HE staining. In ALKO mice with EAE, there was more widespread demyelination accompanied by a greater degree of leukocyte infiltration and dissemination in the parenchyma (Fig.5A–B). Thus, ALKO mice at day 28 after EAE induction showed increased tissue damage in association with more infiltrating cells in the cervical spinal cord.

Fig. 5. LFB staining showing demyelination in the lower cervical spinal cord 28 d after EAE induction.

(A) Patchy areas of demyelination are shown by LFB stain in a WT mouse section on the left, demarcated by curved lines. Counterstaining with cresyl violet highlighted infiltrating cells in the demyelinating areas and in the perivascular region (arrow). In the ALKO section (right), there was a wider area of demyelination seen without LFB staining, and there were more cells in the perivascular region as well as spinal cord parenchyma. Scale bar: 400 µm. (B) Enlarged view of another set of WT and ALKO mice showing that the latter had more cellular infiltration in spinal cord parenchyma (arrows).

The paraventricular region of the hippocampus also had similar changes, with more severe lesions in ALKO than WT mice shown by HE staining (Fig.6). CFA treatment did not induce apparent leukocyte infiltration in either WT (Fig.6A) or ALKO (Fig.6B) mice. In the WT mice with EAE, there was sporadic leukocyte infiltration in the choroid plexus adjacent to the hippocampus (Fig.6C & C’). In the ALKO mice with EAE, leukocyte accumulation was seen in internal leptomeninges and hippocampus (indicated by thick arrows), and there was perivascular cuffing and infiltration in parenchymal tissue (asterisk and thin arrow) (Fig.6D & D’).

Fig. 6. Inflammatory response in hippocampal area of ALKO and FVB WT littermate control mice during MOG-induced EAE, shown by HE staining.

In low magnification images (5×), neither WT (A) nor ALKO (B) mice treated with CFA alone showed apparent inflammatory cell infiltration. In WT mice 28 d after EAE induction (C), there were sporadic inflammatory cells along the choroid plexus of the lateral ventricle adjacent to the hippocampus. In ALKO mice 28 d after EAE induction, there were abundant infiltrating cells in the internal leptomeninges and brain parenchyma as well (D). Higher magnification photomicrographs (20×) of region selected from (C) and (D) are represented as (C’) and (D’). The star shape indicates a representative vessel with perivascular cuffing; the thick arrow indicates leukocyte infiltration and accumulation in internal leptomeninges; the white arrow shows leukocyte infiltration in parenchyma.

LFB staining demarcated the extent of demyelination, and it also reflected the multifocal inflammatory pattern and intense perivascular cuffing by counterstain in the hippocampus. In comparison with the WT mice (Fig.7A and 7C), the ALKO mice on day 28 after EAE induction showed more leukocyte infiltration and leukocyte dissemination (indicated by stars) in the parenchyma (Fig.7B and 7C). This correlated with changes in tissue architecture and demyelination (indicated by arrows in Fig.7D) in hippocampal region.

Fig. 7. LFB myelin staining showing tissue pathology.

In comparison with WT mice with EAE (A), the ALKO section from a mouse 28 d after EAE induction shows multifocal cellular infiltration in a low magnification (5x) image (B). In the respective higher magnification (20x) images from the insets, WT (C) shows fewer foci of cellular infiltration (arrows), with less perivascular cuffing (stars) than the ALKO group (D).

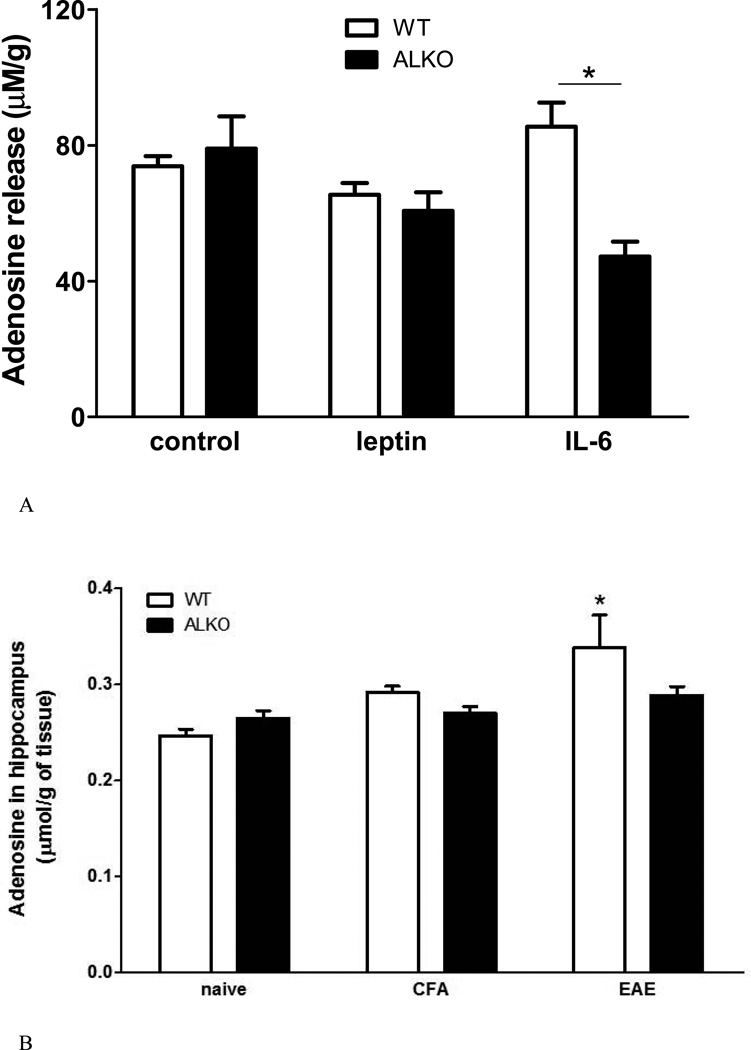

5. Effect of ALKO on adenosine release

Astrocytes from ALKO and WT mice did not differ in basal adenosine release in culture. Leptin treatment did not show a significant effect, probably related to the lack of astrogliosis and robust leptin receptor expression in neonatal astrocytes in culture. IL6 treatment, however, increased adenosine concentration in the WT group (p < 0.05 from the unchallenged cells) but not in the ALKO group (Fig.8A).

Fig. 8. The effect of ALKO on adenosine release.

(A) In cultured primary astrocytes, basal and leptin-stimulated adenosine release at 30 min did not differ between the ALKO and WT mice. IL6 treatment increased adenosine release in the WT mice but not in the ALKO mice (n = 3 /group). *: p < 0.05. (B) In the hippocampus of WT mice, there was more adenosine production 28 d after EAE induction in comparison with the naïve and CFA controls. There was no change in the ALKO mice (n = 3 /group). (C) In the hypothalamus of the same mice shown in Fig.8B, there was no change of adenosine release by EAE induction or ALKO mutation.

For the hippocampus, there was a significant effect of EAE but not of strain. There was no difference in adenosine concentration in the naïve WT and ALKO mice. The group of WT mice 28 days after CFA injection did not show a significant increase of adenosine, but that after EAE induction did. In ALKO mice, neither CFA injection nor EAE induction changed the basal adenosine concentration in the hippocampus 28 days later (Fig.8B).

Adenosine concentration in the hypothalamus did not show significant changes either by the ALKO mutation or EAE induction (Fig.8C). Altogether, the results suggest a region-specific attenuation of astrocytic function, reflected by adenosine release, in the ALKO mice.

Discussion

We show here that ALKO mice had worsening symptoms and greater cell infiltration into the CNS than WT mice after EAE, suggesting a protective role of astrocytic leptin signaling. This is opposite to what has been reported in models of systemic leptin deficiency or leptin receptor dysfunction, or to a beneficial role of the ALKO mutation in response to diet-induced obesity. In response to high-fat diet, both ALKO mice (deficient astrocytic leptin signaling) and ELKO mice (deficient endothelial leptin signaling) show partial rescue of metabolic disturbance (Pan et al., 2012a; Jayaram et al., 2013b). This suggests a facilitatory role of astrocytic and endothelial leptin signaling in the development of obesity. In EAE, however, the outcome was exactly the opposite. There was persistently higher leukocyte infiltration and more demyelination in the ALKO mice at the end of the study. This suggests that astrocytic leptin signaling helps to curtail autoimmune destruction toward the recovery stage of EAE.

The natural course of EAE, regardless of the method of induction and the relapsing pattern (Dal Canto et al., 1995; Simmons et al., 2013), involves three main phases. The latent phase occurs when the peripheral immune system is activated and leukocytes are in the process of interacting with the BBB, where differential permeability to small molecules and regulatory cytokines already shows an increase (Pan et al, 1996). In contrast to a cessation of influx of IL15 (Hsuchou et al., 2009b), an immunomodulatory cytokine with beneficial effects against the worsening of EAE (Wu et al, 2010), leptin transport across the BBB persists and shows an elevation in the hippocampus and cervical spinal cord (Hsuchou et al, 2013).

The acute symptomatic phase of EAE correlates with leukocyte infiltration, CNS inflammation, cellular dysfunction, edema, and further disruption of the BBB. EAE is a Th2 cell predominant autoimmune disorder with regulatory T cells and Th17 cells playing counteracting roles to curtail disease progression. The pattern of activation of myeloid cells, CD4+ Th1 and Th17 cells affects the progression of EAE and was therefore analyzed in this study. The activation of microglia and astrocytes and their potential antigen presentation properties are important to determine the fate of infiltrating leukocytes in regard to proliferation or apoptosis, resulting in either maintenance of symptoms or the third phase of remission, with either tissue destruction or resolution of symptoms.

Astrocytes are involved in multiple steps of EAE progression. They not only affect cerebral metabolism and neuroinflammation, they may also regulate blood-brain and blood-spinal cord barrier functions involved in migration of blood-borne cells. For example, astrocytes inhibit antigen-specific T helper cell responses by inducing CTLA-4 in autoreactive T cells (Gimsa et al., 2004). Astrocytes secrete chemokines and cytokines, and play a dual role in EAE pathology contributing to both demyelination and remyelination processes (Nair et al., 2008). In the presence of co-stimulatory signals, such as serum derived from mice with obesity-induced neuroinflammation (Hsuchou et al., 2012), leptin also facilitates astrogliosis in-vitro and thus probably alters the profile of gliotransmitters. Leptin shows differential effects on astrocytes and neurons, and inhibition of astrocytic activity accentuates neuronal leptin signaling (Pan et al., 2011). Thus, with the presence of robust astrogliosis and upregulation of astrocytic ObR in EAE mice (Wu et al, 2013), leptin signaling in reactive astrocytes clearly affects neuronal function and the final outcome of EAE.

Flow cytometry analysis of leukocytes recovered from spinal cord homogenates indicated that the pattern of cellular infiltration in ALKO and WT mice was similar on day 19 after EAE induction. This suggests that the ALKO mutation did not play a major role in the induction and early progression of EAE. On day 28, the ALKO mice had a significantly higher score and tissue damage than the WT mice. Concurrently, there were more infiltrating cells shown by the counterstaining procedures in HE and LFB staining. This qualitative difference was confirmed by flow cytometry analyses. In the spinal cord of ALKO mice on day 28 after EAE, there was a higher percent of CD4+ T cells and a corresponding reduction of neutrophils. The CD11b+ /Gr1+ neutrophils are myeloid-derived suppressor cells, which inhibit T cell function and enhance the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cell precursors into Th17 cells (Yi et al., 2012). Neutrophils in the CNS have been shown to suppress T cell responses to myelin components or adjuvant (Zehntner et al., 2005). Depletion of peripheral neutrophils on day 8 of EAE can delay the course or attenuate EAE, whereas depletion on day 1–7 is not effective, indicating that neutrophils are involved in the efferent but not the afferent arm of the immune response (McColl et al., 1998). Though increased neutrophil infiltration is typically associated with worsening of disseminated demyelinating diseases (Zehntner et al., 2005), the reduced number of neutrophils in the late stage of EAE in the ALKO mice was apparently associated with their poorer recovery than in the WT mice. This paradox might suggest a compensatory change, or that neutrophils were not the main cellular mediators for the worsening of EAE in the ALKO mice.

To determine whether the increase of CD4+ T cells was associated with greater cell differentiation in the periphery before CNS infiltration, and to evaluate the subsets, we first showed that naïve splenocytes had a similar percent of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. However, splenocytes from ALKO mice at day 28 of EAE indeed had a higher CD4+ percent and more Th1 and Th17 cells shown after 72 h of culture. While seemingly incongruous, the data suggest an active immune process in the ALKO mice at a time when WT mice showed a greater tendency to recover. These cells showed a significant increase of proliferation upon MOG stimulation but not PLP challenge, indicating specificity of antigen recall. Although splenocytes from the WT and ALKO mice showed no difference in antigen recognition and recall, the higher proliferation of Th1, Th17, and total CD4+ T cells after 72 h of culture without antigen re-stimulation suggests an effect of the ALKO mutation on peripheral leukocyte activation. Soluble gliotransmitters exiting the CNS are probably responsible for this effect. Reactive astrocytes, as induced by transient middle cerebral artery occlusion and lipopolysaccharide challenge, are known to induce a myriad of pathways affecting cellular functions and communication with others (Zamanian et al., 2012). In response to MOG stimulation in-vitro, ALKO splenocytes from the EAE mice showed similar recall of CD4+ T cells and Th1 cells as WT mice, but did not mount an increase of Th17 proliferation. This is related to a high baseline of Th17 cells, probably reflecting a compensatory effort of the ALKO mice to overcome the autoimmune destruction at this time.

Adenosine is a major gliotransmitter (Ridet et al., 1997; Halassa et al., 2009). Production of adenosine by adenosine kinase in the astrocytes and its subsequence release may serve as an indicator of astrocyte function. Mass spectrometry analysis showed that IL6 stimulation of both cultured primary astrocytes and hippocampus of mice 28 days after EAE elevated adenosine levels in the WT mice, but not in the ALKO mice. This suggests that leptin signaling maintains astrocytic activity as reflected by adenosine release. The results are in line with reports in the literature that adenosine plays a role in EAE. In one way, adenosine plays a beneficial role. A1 adenosine receptor knockout mice have more severe progressive-relapsing EAE than WT littermates, with more activation of microglia and macrophages, more proinflammatory cytokine expression, and increased demyelination and axonal injury (Tsutsui et al., 2004). In another way, adenosine may worsen EAE by activating different receptor subtypes. When the A2B adenosine receptor is blocked either by an antagonist or in knockout mice, EAE scores are lower, IL-6 production by antigen presentation cells is reduced, and Th17 differentiation is thereby inhibited (Wei et al., 2013). CD73, a cell surface enzyme that catalyzes the breakdown of AMP to adenosine in the purine catabolic pathway, is highly expressed at blood-brain barrier endothelia and choroid plexus epithelia. CD73 knockout mice have reduced leukocyte homing to the CNS and much alleviated EAE symptoms (Mills et al., 2008). Regardless, reduced adenosine release might reflect decreased astrocytic function in the ALKO mice. In ALKO mice with EAE, there appears to be attenuated clearance of infiltrating leukocytes and altered subset composition with a lower percent of neutrophils and elevated CD4+ T cells. As EAE is a CD4 cell driven disease, higher numbers of CD4 cells in the recovery phase may correlate with the higher EAE score in the ALKO mice.

The worsening of EAE in the ALKO mice is opposite from all previous studies showing that peripheral leptin treatment worsens EAE, and from studies in leptin deficient ob/ob mice and leptin receptor deficient db/db mice with defective leptin signaling in all cells showing resistance to EAE induction (Matarese et al., 2001, 2005; Sanna et al., 2003; De Rosa et al., 2006). These earlier studies showed a detrimental role of leptin to enhance autoimmunity.

The novel findings in the ALKO mice indicate cell-specific actions of leptin, as well as potential differences in peripheral and CNS leptin actions as modulated by the BBB. In the peripheral immune system, leptin acts to promote EAE by increasing CD4+ T cell functions (Matarese et al, 2001, 2005; Sanna et al., 2003; De Rosa et al., 2006). In the CNS, ObRb is abundant in neurons, at least in the hypothalamus, whereas ObRa appears to be the predominant isoform in astrocytes (Pan et al., 2008; Hsuchou et al, 2009a). In the EAE mice in our study, significant reduction of neutrophils and elevation of CD4+ T cells mainly occurred on day 28, coinciding with higher EAE scores and worsening histology. The changes are unlikely based on different leptin concentrations, peripheral actions, or BBB transport at this time, but rather result from diminished astrocytic function in the absence of astrocytic leptin signaling.

In summary, in the ALKO mice lacking a signaling leptin receptor in astrocytes, disease incidence and presentation from induction to the peak of EAE scores were similar to those seen in the WT mice. However, the ALKO mice had a worsened recovery phase. At 4 weeks after induction of EAE when WT mice already showed significant recovery, ALKO mice remained weak, showing more CD4+ T cells but fewer neutrophils in the spinal cord, more infiltrating cells in the meninges and CNS parenchyma, and increased demyelination. There was decreased adenosine release in cultured astrocytes and the hippocampus of EAE mice, and increased proliferation of Th1 and Th17 cells as well as total CD4+ T cells ex-vivo. The results suggest that astrocytic leptin signaling has a pronounced protective effect against autoimmune tissue destruction.

Highlight.

ALKO mice show more severe EAE symptoms in the late phase, associated with increased infiltrating cells and demyelination

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH (NS62291 to WP, DK54880 and DK92245 to AJK). The ObR-floxed mice used to generate ALKO mice originated from Dr. Streamson Chua, Jr. (Department of Pediatrics, Albert Einstein Medical College, New York). We thank Ms. Yuping Wang in the lab for providing ALKO mice and maintaining the breeding colony, the Cellular Imaging Core and Ms. Marilyn Dietrich for assistance in flow cytometry, and Dr. Zengbiao Li at Drumetix Laboratories for mass spectrometry analysis of gliotransmitters.

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angelucci F, Mirabella M, Caggiula M, Frisullo G, Patanella K, Sancricca C, Nociti V, Tonali PA, Batocchi AP. Evidence of involvement of leptin and IL-6 peptides in the action of interferon-beta in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Peptides. 2005;26:2289–2293. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayyildiz M, Yildirim M, Agar E, Baltaci AK. The effect of leptin on penicillin-induced epileptiform activity in rats. Brain Res. Bull. 2006;68:374–378. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banks WA, Kastin AJ. Physiological consequences of the passage of peptides across the blood-brain barrier. Rev. Neurosci. 1993;4:365–372. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.1993.4.4.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banks WA, Kastin AJ, Huang W, Jaspan JB, Maness LM. Leptin enters the brain by a saturable system independent of insulin. Peptides. 1996;17:305–311. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(96)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batocchi AP, Rotondi M, Caggiula M, Frisullo G, Odoardi F, Nociti V, Carella C, Tonali PA, Mirabella M. Leptin as a marker of multiple sclerosis activity in patients treated with interferon-beta. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;139:150–154. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00154-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casper KB, Jones K, McCarthy KD. Characterization of astrocyte-specific conditional knockouts. Genesis. 2007;45:292–299. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dal Canto MC, Melvold RW, Kim BS, Miller SD. Two models of multiple sclerosis: experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE) and Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) infection. A pathological and immunological comparison. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1995;32:215–229. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1070320305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Rosa V, Procaccini C, La CA, Chieffi P, Nicoletti GF, Fontana S, Zappacosta S, Matarese G. Leptin neutralization interferes with pathogenic T cell autoreactivity in autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Clin. Invest. 2006;116:447–455. doi: 10.1172/JCI26523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farr SA, Banks WA, Morley JE. Effects of leptin on memory processing. Peptides. 2006;27:1420–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frisullo G, Mirabella M, Angelucci F, Caggiula M, Morosetti R, Sancricca C, Patanella AK, Nociti V, Iorio R, Bianco A, Tomassini V, Pozzilli C, Tonali PA, Matarese G, Batocchi AP. The effect of disease activity on leptin, leptin receptor and suppressor of cytokine signalling-3 expression in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;192:174–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garza JC, Guo M, Zhang W, Lu XY. Leptin increases adult hippocampal neurogenesis in vivo and in vitro. J Biol. Chem. 2008;283:18238–18247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800053200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gimsa U, ORen A, Pandiyan P, Teichmann D, Bechmann I, Nitsch R, Brunner-Weinzierl MC. Astrocytes protect the CNS: antigen-specific T helper cell responses are inhibited by astrocyte-induced upregulation of CTLA-4 (CD152) J. Mol. Med. (Berl) 2004;82:364–372. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0531-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halassa MM, Florian C, Fellin T, Munoz JR, Lee SY, Abel T, Haydon PG, Frank MG. Astrocytic modulation of sleep homeostasis and cognitive consequences of sleep loss. Neuron. 2009;61:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haroon F, Drogemuller K, Handel U, Brunn A, Reinhold D, Nishanth G, Mueller W, Trautwein C, Ernst M, Deckert M, Schluter D. Gp130-dependent astrocytic survival is critical for the control of autoimmune central nervous system inflammation. J. Immunol. 2011;186:6521–6531. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hindinger C, Bergmann CC, Hinton DR, Phares TW, Parra GI, Hussain S, Savarin C, Atkinson RD, Stohlman SA. IFN-gamma signaling to astrocytes protects from autoimmune mediated neurological disability. PLoS. One. 2012;7:e42088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsuchou H, He Y, Kastin AJ, Tu H, Markadakis EN, Rogers RC, Fossier PB, Pan W. Obesity induces functional astrocytic leptin receptors in hypothalamus. Brain. 2009a;132:889–902. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsuchou H, Kastin AJ, Pan W. Blood-borne metabolic factors in obesity exacerbate injury-induced gliosis. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2012;47:267–277. doi: 10.1007/s12031-012-9734-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsuchou H, Kastin AJ, Tu H, Markadakis EN, Stone KP, Wang Y, Heymsfield SB, Chua SC, Jr, Obici S, Magrisso IJ, Pan W. Effects of cell type-specific leptin receptor mutation on leptin transport across the BBB. Peptides. 2011;32:1392–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsuchou H, Mishra PK, Kastin AJ, Wu X, Wang Y, Ouyang S, Pan W. Saturableleptin transport across the BBB persists in EAE mice. J.Mol.Neurosci. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s12031-013-9993-8. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsuchou H, Pan W, Wu X, Kastin AJ. Cessation of blood-to-brain influx of interleukin-15 during development of EAE. J. Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009b;29:1568–1578. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jayaram B, Khan RS, Kastin AJ, Hsuchou H, Wu X, Pan W. Protective Role of Astrocytic Leptin Signaling Against Excitotoxicity. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2013a;49:523–530. doi: 10.1007/s12031-012-9924-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jayaram B, Pan W, Wang Y, Hsuchou H, Mace A, Cornelissen-Guillaume GG, Mishra PK, Koza RA, Kastin AJ. Astrocytic leptin-receptor knockout mice show partial rescue of leptin resistance in diet-induced obesity. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013b;114:734–741. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01499.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juhler M, Barry DI, Offner H, Konat G, Klinken L, Paulson OB. Blood-brain and blood-spinal cord barrier permeability during the course of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in the rat. Brain Res. 1984;302:347–355. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90249-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kastin AJ, Pan W. Concepts for Biologically Active Peptides. Curr. Pharm Des. 2010;16:3390–3400. doi: 10.2174/138161210793563491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelchtermans H, Billiau A, Matthys P. How interferon-gamma keeps autoimmune diseases in check. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lanens D, Van der Linden A, Gerrits PO, ‘s-Gravenmade EJ. In vitro NMR micro imaging of the spinal cord of chronic relapsing EAE rats. Magn Reson. Imaging. 1994;12:469–475. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(94)92541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Q, Powell N, Zhang H, Belevych N, Ching S, Chen Q, Sheridan J, Whitacre C, Quan N. Endothelial IL-1R1 is a critical mediator of EAE pathogenesis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2011;25:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matarese G, Carrieri PB, La CA, Perna F, Sanna V, De RV, Aufiero D, Fontana S, Zappacosta S. Leptin increase in multiple sclerosis associates with reduced number of CD4(+)CD25+ regulatory T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:5150–5155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408995102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matarese G, Sanna V, Di Giacomo A, Lord GM, Howard JK, Blood SR, Lechler RI, Fontana S, Zappacosta S. Leptin potentiates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in SJL female mice and confers susceptibility to males. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001;31:1324–1332. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200105)31:5<1324::AID-IMMU1324>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McColl SR, Staykova MA, Wozniak A, Fordham S, Bruce J, Willenborg DO. Treatment with anti-granulocyte antibodies inhibits the effector phase of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 1998;161:6421–6426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McMinn JE, Liu SM, Dragatsis I, Dietrich P, Ludwig T, Eiden S, Chua SC., Jr An allelic series for the leptin receptor gene generated by CRE and FLP recombinase. Mamm. Genome. 2004;15:677–685. doi: 10.1007/s00335-004-2340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McMinn JE, Liu SM, Liu H, Dragatsis I, Dietrich P, Ludwig T, Boozer CN, Chua SC., Jr Neuronal deletion of Lepr elicits diabesity in mice without affecting cold tolerance or fertility. Am. J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:E403–E411. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00535.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mills JH, Thompson LF, Mueller C, Waickman AT, Jalkanen S, Niemela J, Airas L, Bynoe MS. CD73 is required for efficient entry of lymphocytes into the central nervous system during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:9325–9330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711175105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nair A, Frederick TJ, Miller SD. Astrocytes in multiple sclerosis: a product of their environment. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65:2702–2720. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8059-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan W, Banks WA, Kennedy MK, Gutierrez EG, Kastin AJ. Differential permeability of the BBB in acute EAE: enhanced transport of TNF- Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:E636–E642. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.4.E636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan W, Hsuchou H, Cornelissen-Guillaume GG, Jayaram B, Wang Y, Tu H, Halberg F, Wu X, Chua SC, Jr, Kastin AJ. Endothelial leptin receptor mutation provides partial resistance to diet-induced obesity. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012a;112:1410–1418. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00590.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan W, Hsuchou H, He Y, Sakharkar A, Cain C, Yu C, Kastin AJ. Astrocyte Leptin Receptor (ObR) and Leptin Transport in Adult-Onset Obese Mice. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2798–2806. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pan W, Hsuchou H, Jayaram B, Khan RS, Huang EYK, Wu X, Chen C, Kastin AJ. Leptin action on non-neuronal cells in the CNS: potential clinical implications. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012b;1264:64–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06472.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pan W, Hsuchou H, Xu CL, Wu X, Bouret SG, Kastin AJ. Astrocytes modulate distribution and neuronal signaling of leptin in the hypothalamus of obese Avy mice. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2011;43:478–484. doi: 10.1007/s12031-010-9470-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pan W, Kastin AJ. Adipokines and the blood-brain barrier. Peptides. 2007;28:1317–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pino PA, Cardona AE. Isolation of brain and spinal cord mononuclear cells using percoll gradients. J. Vis. Exp. 2011 Feb;2(48) doi: 10.3791/2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ridet JL, Malhotra SK, Privat A, Gage FH. Reactive astrocytes: cellular and molecular cues to biological function. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:570–577. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanna V, Di GA, La CA, Lechler RI, Fontana S, Zappacosta S, Matarese G. Leptin surge precedes onset of autoimmune encephalomyelitis and correlates with development of pathogenic T cell responses. J Clin. Invest. 2003;111:241–250. doi: 10.1172/JCI16721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simmons SB, Pierson ER, Lee SY, Goverman JM. Modeling the heterogeneity of multiple sclerosis in animals. Trends Immunol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang BL. Leptin as a neuroprotective agent. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;368:181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsutsui S, Schnermann J, Noorbakhsh F, Henry S, Yong VW, Winston BW, Warren K, Power C. A1 adenosine receptor upregulation and activation attenuatesneuroinflammation and demyelination in a model of multiple sclerosis. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:1521–1529. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4271-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wei W, Du C, Lv J, Zhao G, Li Z, Wu Z, Hasko G, Xie X. Blocking A2B adenosine receptor alleviates pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis via inhibition of IL-6 production and Th17 differentiation. J. Immunol. 2013;190:138–146. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu X, Mishra PK, Hsuchou H, Kastin AJ, Pan W. Upregulation of astrocytic leptin receptor in mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2013;49:446–456. doi: 10.1007/s12031-012-9825-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu X, Pan W, He Y, Hsuchou H, Kastin AJ. Cerebral interleukin-15 shows upregulation and beneficial effects in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2010;223:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu L, Rensing N, Yang XF, Zhang HX, Thio LL, Rothman SM, Weisenfeld AE, Wong M, Yamada KA. Leptin inhibits 4-aminopyridine- and pentylenetetrazole-induced seizures and AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission in rodents. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:272–280. doi: 10.1172/JCI33009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yi H, Guo C, Yu X, Zuo D, Wang XY. Mouse CD11b+Gr-1+ myeloid cells can promote Th17 cell differentiation and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 2012;189:4295–4304. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zamanian JL, Xu L, Foo LC, Nouri N, Zhou L, Giffard RG, Barres BA. Genomic analysis of reactive astrogliosis. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:6391–6410. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6221-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zehntner SP, Brickman C, Bourbonniere L, Remington L, Caruso M, Owens T. Neutrophils that infiltrate the central nervous system regulate T cell responses. J. Immunol. 2005;174:5124–5131. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.5124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]