Abstract

Although drug and alcohol treatment are common requirements in the U.S. criminal justice system, only a minority of clients actually initiate treatment. This paper describes a two-session, web-based intervention to increase motivation for substance abuse treatment among clients using illicit substances. MAPIT (Motivational Assessment Program to Initiate Treatment) integrates the extended parallel process model, motivational interviewing, and social cognitive theory. The first session (completed near the start of probation) targets motivation to complete probation, to make changes in substance use (including treatment initiation), and to obtain HIV testing and care. The second session (completed approximately 30 days after session 1) focuses on goal setting, coping strategies, and social support. Both sessions can generate emails or mobile texts to remind clients of their goals. MAPIT uses theory-based algorithms and a text-to-speech engine to deliver custom feedback and suggestions. In an initial test, participants indicated that the program was respectful, easy to use, and would be helpful in making changes in substance use. MAPIT is being tested in a randomized trial in two large U.S. probation agencies. MAPIT addresses the difficulties of many probation agencies to maximize client involvement in treatment, in a way that is cost effective and compatible with the existing service delivery system.

Keywords: criminal justice, substance abuse, treatment initiation, HIV, e-Health

Introduction

Probation, the largest segment of the criminal justice system, represents nearly 6 million people under supervision, 3.5 million of whom are in need of substance abuse treatment (Taxman, Perdoni, & Caudy, 2013). Although more than half of probation offenders have drug treatment conditions, only 17% report participating in treatment (Karberg, 2005). The lack of treatment compliance is an enormous and costly challenge to the criminal justice system and to society. Part of the challenge results from system-level barriers such as lack of services (Chandler, Fletcher, & Volkow, 2009; Taxman, Perdoni, & Harrison, 2007) and attitudes of justice actors that undermine the value of treatment (Farabee et al., 1999; Taxman, 1998). A related challenge is that, despite legal pressure, offenders may be insufficiently motivated to participate in treatment.

A few recent programs have targeted motivation as a precursor to clinical services. For instance, there is evidence that brief interventions that draw from motivational interviewing (MI) and cognitive behavioral theory can increase treatment readiness (Lieberman & Massey, 2008) and reduce substance use (Carroll et al., 2009; Hester, Squires, & Delaney, 2005; Ondersma, Svikis, & Schuster, 2007; Riper et al., 2008). None of these approaches, however, have been tested specifically with a criminal justice population. In addition, there is emerging evidence that a syndemic focus on more than one related behavior can promote healthy change across behaviors, without dilution of effects (Floyd et al., 2007; Ingersoll et al., 2005). Interventions that target more than one related area may lead to more robust changes, due to increased perceptions of choice and control (Wagner & Ingersoll, 2009). Given that rates of HIV/AIDS among probationers are approximately three times higher than those of the general population (Maruschak, 2007), it is important to target behaviors that put substance-using probationers at risk for acquiring sexually transmitted infections such as HIV/AIDS. In fact, research has suggested that criminal justice involvement is an independent correlate of sexual risk behavior and HIV because it 1) increases contact with high-risk networks, 2) weakens social cohesion and support networks, and 3) increases social instability and disenfranchisement (Khan, Epperson, & Comfort, 2012). Thus, a focus on three related behaviors—criminal behavior, substance abuse, and HIV testing and care—is well matched to the population and can have the collateral benefit of facilitating change in all three behaviors, thereby addressing both health and safety concerns.

In this process, automated interventions have several potential advantages over face-to-face interventions: 1) they require little or no staff contact, which may increase cost-effectiveness; 2) they can allow for automatic data collection and follow-up; and 3) they can be disseminated with little loss of fidelity (Hester & Miller, 2006). In addition, a growing body of evidence suggests that information gathered from computer-based assessments may be more valid than information gathered from face-to face interviews, particularly for sensitive topics such as drug use and HIV risk (Joinson, 2007). Several automated interventions have shown efficacy at reducing alcohol and drug use, with effects in some cases that are comparable to in-person interventions (Moore, Fazzino, Garnet, Cutter, & Barry, 2011; Portnoy, Scott-Sheldon, Johnson, & Carey, 2008; Rooke, Thorsteinsson, Karpin, Copeland, & Allsop, 2010). This paper describes the development of a web-based intervention to increase substance abuse treatment initiation, probation compliance, and HIV testing and care, among criminal justice clients. The program integrates therapeutic and criminal justice constructs, and uses recent technological advances to customize the program and assist with later change efforts.

MAPIT Overview

MAPIT (Motivational Assessment Program to Initiate Treatment) is a web-based application, consisting of two, 45-minute modules. 1 MAPIT has three behavioral targets: 1) substance abuse, including treatment initiation and engagement; 2) probation compliance and future involvement in criminal behavior, and 3) HIV testing and care. The program is completed near the start of probation, during a time when clients are making critical decisions about ways to address mandated conditions. MAPIT is fully compatible with the existing probation system and places minimal demands on probation staff. The intervention logic and script were developed by the project PI’s (SW and FT), with input from consultants (SO and KI) and project staff (JL, MR, and MR). We were unable to identify an authoring software that could accommodate the scope of the program, and thus we used a custom programming solution that included JavaScript, .NET, integrated text-to-speech components, and database storage technologies. 2 To ensure ease of use, spoken and written text were set at the 6th grade level. In the clinical trial (described below), the program is completed in the probation office on a tablet computer, immediately following a baseline research assessment.

MAPIT draws from three main theories. First, we used the extended parallel process model (EPPM; Murray-Johnson et al., 2005; Witte, Cameron, McKeon, & Berkowitz, 1996) to develop risk messages related to our three behavioral targets. The EPPM suggests that optimal risk communication messages include personally relevant (susceptibility) and serious (severity) information, balanced by self- and response-efficacy messages to reduce potential harms. MAPIT shows clients not only their risk of probation violation based on historical factors, but also what future behaviors are most likely to decrease that risk. Second, we used social cognitive theory (SCT; Bandura, 1986) to show how clients compare to others in terms of substance use and probation risk, and to frame suggestions in terms of the kinds of strategies that other people use to change both behaviors. At key junctures, the program also includes short video testimonials from other individuals on probation to promote engagement (“What was going through your mind when you first got on probation?”) and to model responses to program content (“Who have been some people who have been most helpful to you?”). Finally, we used elements of MI (Miller & Rollnick, 2012), a person centered, directive counseling style. In terms of the MI process, engagement is promoted through an intervention “tone” that emphasizes autonomy, collaboration and evocation, as well as through the use of open questions, affirmations, and summary statements. Focusing includes activities to identify strategies that are more likely to produce a more successful probation outcome. Evoking strategies include personalized, dynamic feedback, targeted open questions and selective reinforcement of responses. Finally, planning is addressed in modules that cover goal setting, social support, and text/email reminders. Although many MI techniques are beyond the reach of an automated program, a text-to-speech engine (described below) enabled us to provide a much more tailored experience than interventions that rely on pre-recorded video or audio tracks.

Visit 1: Increasing Motivation

The first program visit (completed near the start of probation) targets motivation to complete probation, make changes in substance use behaviors (including treatment initiation), and obtain HIV testing and care. Information from the baseline research assessment is automatically imported into the intervention. The first section (illustrated in Figure 1) shows the user’s estimated probation outcome based on static and dynamic criminogenic risk, a set of factors that are linked to offending behavior (Andrews & Bonta, 2003); many of these behaviors are also linked to substance use. The program illustrates that, although historical factors such as age of first arrest and severity of present offense (i.e., static risk) can influence probation outcome, other modifiable factors such as peer group, substance use, and employment (i.e., dynamic risk) also influence outcome. Our dynamic risk factors include family, friends, education/employment, alcohol use, and drug use. After a brief description of each area, the user is invited to assemble different hypothetical combinations of behavior changes to see how different yes/no combinations would affect their estimated probation outcome. The section ends by asking the client to indicate their most important reasons for completing probation. Based on the pattern of responses, the program summarizes the main themes in the user’s reasons for wanting to complete probation. The person’s overall motivation to complete probation and “get on with your life” is used to increase motivation to engage in substance abuse treatment and other pro-social behaviors.

Figure 1.

Screenshot of Visit 1 criminal justice risk section.

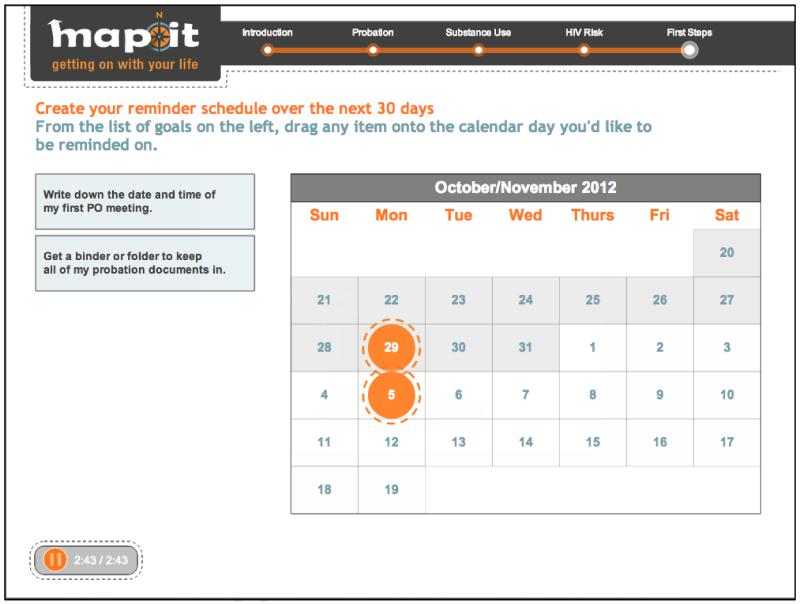

The second section provides a summary of alcohol and drug use, including a comparison to age- and gender-specific norms, a risk indicator, and a profile of alcohol and drug consequences adapted from the Inventory of Drug Use Consequences (InDUC; Tonigan & Miller, 2002). The third section summarizes risk behaviors and screening status and makes recommendations for HIV testing based on CDC guidelines (Branson et al., 2006). The final section of the program (illustrated in Figure 2) focuses on planning. It begins by asking the client to sort a list of potential reasons for engaging in substance abuse treatment, adapted from the Problem Recognition subscale of the Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (SOCRATES; Miller & Tonigan, 1996). Based on the client’s ranking, the program provides a summary of his/her most important intrinsic reasons for engaging in treatment, and assists the person with compiling a list of goals for the next month. Recent Cochrane reviews have found that text messaging enhances medication adherence and healthcare attendance (Car, Gurol-Urganci, de Jongh, Vodopivec-Jamsek, & Atun, 2012; Horvath, Azman, Kennedy, & Rutherford, 2012), and thus the program concludes by offering to email or text reminders about goals at specific times indicated by the client. The first session generates a 3-4 page worksheet-style summary printout for clients.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of Visit 1 planning section.

Visit 2: Planning for Change

The second program visit (completed approximately 30 days after the first session) focuses on goal setting, coping strategies, and social support. The program begins by reviewing the client’s motivation and progress toward goals that were selected at the last visit. The second section focuses on developing effective strategies for change. Using items modified from the Effectiveness of Coping Behaviors Inventory (Litman, Stapleton, Oppenheim, Peleg, & Jackson, 1984), the program gives a summary of the client’s preferred strategies for dealing with cravings, and recommends additional strategies that are similar to those preferred by the client. Clients can add strategies to a master list that will be included in their summary printout. The third section helps clients to identify people who would help them to make changes in substance use. Clients are asked to list people in five key areas (i.e., friends, family, religious, support groups, job/school), and identify which people are already supportive or would be supportive if asked to help make changes in substance use. Clients are asked to write a sentence or two describing how they might ask each person for help. Finally, the program offers to e-mail or text reminders about goals at times indicated by the client. The second session generates a 3-4 page worksheet-style summary printout.

Program Development

Tailoring

The program uses a number of technical strategies to tailor questions and summaries. One basic strategy is to frame questions to capture limited response sets. For instance, the program asks clients about their reaction to risk information: “What do you think? Was your risk higher, lower, or about what you expected?” Based on the client’s response, the program provides one of three reflections. Similarly, the readiness ruler, a common strategy in brief MI interactions, was structured to produce different response “blocks.” In MAPIT, the question,“On a scale of 1-10, how committed are you right now to completing substance abuse treatment?” produces four possible blocks (i.e., 1, 2-4, 5-6, 7-10), which result in different visual/audio responses (i.e., not at all committed, a little committed, somewhat committed, very committed). For example, here is a hypothetical response to a person who has indicated a fairly low level of commitment (e.g., “3”) to finishing probation.

OK. You’re somewhat committed to finishing probation, but the number is on the low side. If you’re not sure where to start, I can show you how other people get the ball rolling, and you can tell me if it sounds right. You know, I’m just a computer. Sometimes I get it wrong, so feel free to use the information to make the choice that’s right for you.

Finally, the program uses more complex question sets to identify themes in how users are responding. Where possible, we adapted existing questionnaires on motivation, consequences, and efficacy to develop summary and suggestion tracks. For instance, one activity asks clients to indicate whether different reasons are “Not at All,” “Somewhat,” or “Very Much” part of their motivation to finish probation. The program then responds differentially based on whether the user’s motivation has more to do with relationships, legal pressures, shame, time, financial, or freedom/monitoring. This tailored motivational summary appears at critical junctures in the program, such as before asking for a commitment to action. In this sample, the user has more strongly endorsed reasons related to relationships (e.g., “To set an example for my family”), and thus the program responds with a summary highlighting this theme.

Everyone has reasons for wanting to finish probation. For you, some of the most important reasons are because of your relationships. People may feel obligated to family or friends who have helped them out in the past. Other people talk about wanting to set an example for their children or younger siblings. You want to make life better for others.

Based on the user’s response patterns, the program can make additional suggestions that are similar to those endorsed by the client. For instance, one activity asks clients to indicate whether different kinds of behavior strategies “Would Not Work,” “Might Work,” or “Would Definitely Work” for them. A person who more strongly endorses strategies related to changing their environment might benefit from suggestions such as to avoid places where they used to use drugs, or to spend more time with children or family. Similarly, a person who endorses strategies related to relationships might benefits from suggestions to get in touch with old friends who do not use, or attend a support group. Clients can choose any of the suggestions to add to a list that will reappear later. Here is what the program might say:

People have all different ways of approaching change. What works for one person might not work for another. In looking at your answers, the kinds of strategies you would be most likely to use involve —. Those are great ideas. People like you are more likely to use strategies like — or —. Click on any of these to add it to your list of strategies, and I’ll be sure to print it out at the end, just in case you want to remember it.

Voice and Tone

A major constraint for automated programs is the extent to which current technology can provide a tailored experience for every individual, in effect, the extent to which it feels like the program is really “listening” to clients. We chose to use a text-to-speech engine that generates a natural-sounding synthetic voice from a text script (for a sample, see http://www.neospeech.com/). With a text-to-speech engine, the narration is generated in real-time; all possible text combinations are available, but are not assembled until the program determines a response. The decision to use synthetic narration opened up many more possibilities for tailoring the interaction in a fine-grained way; for instance, we were able to customize wording within a sentence, offering hundreds of possible combinations within a single paragraph.

After developing a basic introduction script, we conducted qualitative research to determine a narrator voice and “personality”. Synthetic voices, like human voices, vary on gender, pitch, and regional dialect. In addition to choices about gender and pitch, we were interested in the preferred personality “tone” of the narrator. For example, should the narrator have a name and refer to itself in the first person? Should it make reference to its voice quality, or should it assume a more impersonal “expert” tone? We conducted two focus groups of 16 individuals receiving substance abuse treatment in Dallas, TX. A basic script was played using a variety of human and synthetic voices, and participants were asked to rate the voices on different dimensions (e.g., clarity, likeability, professionalism, overall preference). Audio recordings of the focus groups were transcribed, coded using content analysis, and analyzed using NVivo. In general, participants preferred a female voice that was bright, friendly, and self-aware. Most participants indicated that an automated voice was preferable if the narration could be tailored to them. These overall impressions led us to choose “Jennifer,” a female, lower pitch voice, with a non-specific regional dialect. In addition, we brightened the overall tone of the narration to make it sound more like friendly, colloquial language.

Initial Testing

Once the program was completed, we conducted a pilot test among 21 clients who would have been eligible to participate in the clinical trial, described below (n=10 for Baltimore, n=11 for Dallas). After finishing the program, clients completed a Likert-style response form (1 = “Not at All,” 5 = “Very Much”), and were also asked to give their written impressions of the program. Overall, respondents were quite positive about the program’s format, narration, integration of data, and summary reports. Respondents also felt that the program would help them to be more successful on probation and in treatment (mean ratings of 4.6/5.0 and 4.7/5.0, respectively). Written comments most commonly praised the accuracy and usefulness of the program. The most interesting parts were “how the program knew what would work best for me,” “how the program charted my drug use and problems,” “[finding out] how many people smoke less than me,” and “listening to [other] people’s reasons” for completing probation.

In the ongoing clinical trial, we examined user data from the first 20 cases randomized to MAPIT (n=8 for Baltimore; n=12 for Dallas). Overall, participants indicated they were highly committed to successfully complete treatment and to finish probation (mean initial commitment from 1-10 = 8.0 for treatment; 9.1 for probation). The most common reasons for wanting to complete probation involved relationships (55% rated most important) and financial reasons (20% rated as most important). Thirty percent of participants chose to see HIV testing options. The most common early probation goals included, “Write down the date and time of my first PO meeting” (27% selected); “Make a list of my biggest worries about completing probation and share it with my officer” (27%), and; “Get a binder or folder to keep all of my probation documents in” (24%). The most common early treatment goals included, “Make a list of some things I could do to stay sober” (32%); “Talk to someone with clean time to see how they did it” (27%), and; “Put a number in my phone of someone I could call if I needed to talk” (27%). About two thirds of participants elected to receive reminders about their probation and treatment goals (Email= 25%; Text=35%; None=35%), which is remarkable given that reminders were voluntary, and involved no additional rewards or oversight by a probation officer.

Evaluation Strategy

MAPIT is being evaluated in a randomized, controlled trial. A total of 600 probation clients in two large urban probation departments (Baltimore, MD and Dallas, TX) are being randomized to receive: 1) in-person MI; 2) a motivational computer program (described here as “MAPIT”); or 3) probation intake and supervision as usual. Randomization is blocked based on criminal justice risk score to determine whether the program works with both low/medium, and high-risk offenders. Eligibility criteria include being over 18 years old, a recent court date, and recent drug use or heavy alcohol use. Follow-up assessments will be conducted at 2, 6 and 12 months. Primary outcomes include initiation, engagement, and retention in substance abuse treatment and HIV/AIDS testing; secondary outcomes include drug and alcohol use, risky sexual behaviors, probation progress, and criminal behavior. The two study sites, which vary in terms of organization, client demography, and treatment integration, will help determine whether the interventions are robust in different settings. If our results generalize across probation agencies, this holds the potential to greatly improve early treatment motivation among the over 3.5 million probationers in need of these services, with the eventual goal of reducing substance abuse and criminal behavior, and increasing the number of people who obtain HIV testing and care.

Discussion

With nearly 40% of new prison intakes resulting from probation failures (Guerino, Harrison, & Sabol, 2011), as well as the high concentration of substance abuse and HIV risk behaviors among probationers, there is a need to address motivation to change among probationers. Part of the solution involves educating offenders about the cadre of activities that can reduce their risk for further interactions with the criminal justice system. In this respect, potentially cost-effective tools such as MAPIT are particularly attractive in the criminal justice system, which employs few clinical staff.

MAPIT fits into a category of “persuasive” technology that is designed to change attitudes or behaviors through encouragement rather than coercion. According to Fogg (2003), technology can be persuasive by making something easier to do, guiding people through a process, or presenting calculations or feedback in a motivational way. Automated interventions are likely to grow and evolve as new technology becomes available. Future interventions may be able to gather information from users’ facial expressions, gestures, response latency, and other forms of passive input. Pre-defined algorithms could use such data to personalize and increase the efficacy of the intervention. In addition, many techniques from evidence-based in-person approaches can be applied to computing interactions. In fact, there is evidence that people treat computers like real people in many ways: people are “polite” to computers, make assumptions about computing “personalities”, and have similar reactions to being praised by a computer or a live person (Nass & Yen, 2010). Future research will undoubtedly examine moderators and mediators of efficacy, and may hold the potential for technology-delivered interventions—with their superior ability to gather information from various iterations—to inform more general conceptions of therapeutic change. Notably, the use of web applications also allow improved versions to be easily and immediately implemented on a large scale.

MAPIT, which blends psychological and criminal justice theories with practical user-related features, is part of a new wave of products that are designed with dissemination in mind. Future research in e-health applications will help determine which routes (e.g., mobile, kiosk, personal computer) and structures (e.g., mandates, education, incentives) are most compatible in each setting. Specific to the criminal justice system, automated programs must continue to integrate therapeutic concepts with broader health and safety concerns. Finally, future efforts will almost certainly include examinations of how best to implement computer-delivered interventions in “real world” settings, such as schools, workplaces, primary care, and social services settings. MAPIT illustrates one way to use theory and technology to target three syndemic behaviors commonly experienced by persons on probation.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA029010-01; Multiple PI: Walters/Taxman).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Samples of the program can be viewed at: http://youtu.be/9yV6bTn1tVE, http://youtu.be/XEZ5o48WwTg, http://youtu.be/u2SHWG0QXe8, http://youtu.be/wMShVdPpcsw

MAPIT was programmed by Blu SKY, a web and mobile application development company located in Bellingham, WA (http://bluscs.com/).

Contributor Information

Scott T. Walters, University of North Texas Health Science Center.

Steven J. Ondersma, Wayne State University

Karen Ingersoll, University of Virginia.

Mayra Rodriguez, University of North Texas Health Science Center.

Jennifer Lerch, George Mason University.

Matthew E. Rossheim, University of North Texas Health Science Center

Faye S. Taxman, George Mason University

References

- Andrews DA, Bonta J. The psychology of criminal conduct. 3rd ed. Anderson Publishing Co; Cincinnati: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, Janssen RS, Taylor AW, Lyss SB, Clark JE. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17. Practice Guideline. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Car J, Gurol-Urganci I, de Jongh T, Vodopivec-Jamsek V, Atun R. Mobile phone messaging reminders for attendance at healthcare appointments. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7:CD007458. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007458.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Ball SA, Martino S, Nich C, Babuscio TA, Rounsaville BJ. Enduring effects of a computer-assisted training program for cognitive behavioral therapy: a 6-month follow-up of CBT4CBT. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;100(1-2):178–181. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler RK, Fletcher BW, Volkow ND. Treating drug abuse and addiction in the criminal justice system: improving public health and safety. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301(2):183–190. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farabee D, Prendegrast M, Cartier J, Wexler H, Knight K, Anglin MD. Barriers to Implementing Effective Correctional Drug Treatment Programs. The Prison Journal. 1999;79(2):150–162. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd RL, Sobell M, Velasquez MM, Ingersoll K, Nettleman M, Sobell L, Nagaraja J. Preventing alcohol-exposed pregnancies: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogg BJ. Persuasive technology: using computers to change what we think and do. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers; Amsterdam; Boston: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Guerino P, Harrison PM, Sabol WJ. Prisoners in 2010. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; Washington DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hester RK, Miller JH. Computer-based tools for diagnosis and treatment of alcohol problems. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29(1):36–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester RK, Squires DD, Delaney HD. The Drinker’s Check-up: 12-month outcomes of a controlled clinical trial of a stand-alone software program for problem drinkers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28(2):159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath T, Azman H, Kennedy GE, Rutherford GW. Mobile phone text messaging for promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;3:CD009756. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll KS, Ceperich SD, Nettleman MD, Karanda K, Brocksen S, Johnson BA. Reducing alcohol-exposed pregnancy risk in college women: initial outcomes of a clinical trial of a motivational intervention. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;29(3):173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.06.003. doi: S0740-5472(05)00134-0 [pii] 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joinson AN, McKenna K, Postmes T, Reips U-D. The Oxford handbook of Internet psychology. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Karberg JC, James DJ. Substance dependence, abuse and treatment of jail inmates, 2002. Dept of Justice Publication; Washington, DC: 2005. NCJ 209588. [Google Scholar]

- Khan M, Epperson M, Comfort M. Criminal Justice Involvement and HIV Risk Model: A Novel Conceptual Model That Describes the Influence of Arrest and Incarceration on STI/HIV Transmission. Paper presented at the American Public Health Association; San Francisco, CA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman DZ, Massey SH. Pathways to change: The effect of a Web application on treatment interest. American Journal on Addictions. 2008;17(4):265–270. doi: 10.1080/10550490802138525. doi: Doi 10.1080/10550490802138525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litman GK, Stapleton J, Oppenheim AN, Peleg M, Jackson P. The relationship between coping behaviours, their effectiveness and alcoholism relapse and survival. British Journal of Addiction. 1984;79(3):283–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1984.tb00276.x. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruschak L. HIV in prisons, 2002. U.S. Dept of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; Washington DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. 3rd Ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Assessing drinkers’ motivation for change: The stages of change readiness and treatment eagerness scale (SOCRATES) Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1996;10(2):81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Moore BA, Fazzino T, Garnet B, Cutter CJ, Barry DT. Computer-based interventions for drug use disorders: a systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2011;40(3):215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray-Johnson L, Witte K, Boulay M, Figueroa ME, Storey D, Tweedie I. Using health education theories to explain behavior change: a cross-country analysis. 2000-2001. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2005;25(1-2):185–207. doi: 10.2190/1500-1461-44GK-M325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nass CI, Yen C. The man who lied to his laptop: what machines teach us about human relationships. Current; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ondersma SJ, Svikis DS, Schuster CR. Computer-based brief intervention: A randomized trial with postpartum women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32(3):231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portnoy DB, Scott-Sheldon LA, Johnson BT, Carey MP. Computer-delivered interventions for health promotion and behavioral risk reduction: A meta-analysis of 75 randomized controlled trials, 1988-2007. Preventive Medicine. 2008;47(1):3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riper H, Kramer J, Smit F, Conijn B, Schippers G, Cuijpers P. Web-based self-help for problem drinkers: A pragmatic randomized trial. Addiction. 2008;103(2):218–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooke S, Thorsteinsson E, Karpin A, Copeland J, Allsop D. Computer-delivered interventions for alcohol and tobacco use: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2010;105(8):1381–1390. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taxman FS. Reducing Recidivism Through A Seamless System of Care: Components of Effective Treatment, Supervision, and Transition Services in the Community. Office of National Drug Control Policy; Washington D.C.: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Taxman FS, Perdoni ML, Caudy M. The plight of providing appropriate substance abuse treatment services to offenders: Modeling the gaps in service delivery. Victims and Offenders. 2013;8(1):70–93. [Google Scholar]

- Taxman FS, Perdoni ML, Harrison LD. Drug treatment services for adult offenders: The state of the state. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;32(3):239–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Miller WR. The inventory of drug use consequences (InDUC): Test-retest stability and sensitivity to detect change. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16(2):165–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner CC, Ingersoll KS. Beyond behavior: eliciting broader change with motivational interviewing. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(11):1180–1194. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20639. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte K, Cameron KA, McKeon JK, Berkowitz JM. Predicting risk behaviors: development and validation of a diagnostic scale. J Health Commun. 1996;1(4):317–341. doi: 10.1080/108107396127988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]