Abstract

Background

Timely initiation of combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) in eligible HIV-infected patients is associated with substantial reductions in mortality and morbidity. Nigeria has the second largest number of persons living with HIV/AIDS in the world. We examined patient characteristics, time to ART initiation, retention and mortality at five rural facilities in Kwara and Niger states of Nigeria.

Methods

We analyzed program-level cohort data for HIV-infected, ART-naïve clients (≥15 years) enrolled from June 2009-February 2011. We modeled the probability of ART initiation among clients meeting national ART eligibility criteria using logistic regression with splines.

Results

We enrolled 1,948 ART-naïve adults/adolescents into care, of whom 1174 were ART eligible (62% female). Only 74% of eligible patients (n=869) initiated ART within 90 days post-enrollment. The median CD4+ count for eligible clients was 156 cells/μL [IQR: 81–257], with 67% in WHO stage III/IV disease. Adjusting for CD4+ count, WHO stage, functional status, hemoglobin, body mass index, sex, age, education, marital status, employment, clinic of attendance, and month of enrollment, we found that immunosuppression (CD4 350 vs. 200, odds ratio (OR)=2.10 [95%CI: 1.31, 3.35], functional status (bedridden vs. working, OR=4.17 [95%CI: 1.63–10.67]), clinic of attendance (Kuta hospital vs. referent: OR=5.70 [95%CI:2.99–10.89]), and date of enrollment (December 2010 vs. June 2009: OR=2.13 [95%CI:1.19–3.81]) were associated with delayed ART initiation.

Conclusion

Delayed initiation of ART was associated with higher CD4+ counts, lower functional status, clinic of attendance, and later dates of enrollment among ART-eligible clients. Our findings provide targets for quality improvement efforts that may help reduce attrition and improve ART uptake in similar settings.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Nigeria, antiretroviral therapy, implementation science, outcomes, PEPFAR, retention, mortality

INTRODUCTION

Nigeria is home to the second-largest number of people living with HIV in the world (est. 3.3 million), after South Africa.1,2 The U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) has made substantial contributions to stemming the tide of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Nigeria, but there is still much to be done. While PEPFAR supported provision of comprehensive antiretroviral treatment (ART) to 334,700 Nigerians in 2010, national treatment coverage from all sources was 26%, the lowest among all 15 PEPFAR focus countries.3 Similarly, only 14.7% of 3351 health facilities nationwide offered ART services in 2011, despite a 25% increase (from 393 to 491) in the number of ART sites between 2009 and 2011.4 The ability to access HIV treatment services beyond larger cities remains limited.3–6

Adding to the problem of lack of access to ART are delays in initiation of ART in treatment-eligible patients. Delays in initiation of ART could be due to many reasons, including pre-ART attrition and system-mandated waits to allow for pre-treatment counseling.7–9 These delays are associated with excess rates of preventable morbidity and mortality, especially in ART-eligible patients with advanced HIV disease who are already at elevated risk of death.10–13 Compared to studies on adherence and retention after commencement of ART, there is a relative dearth of literature on factors associated with delayed ART initiation in the pre-ART phase.10 Such research could contribute to the development of programmatic strategies to minimize holdups in treatment initiation, thereby curtailing high levels of early mortality seen in HIV-infected patients in resource-limited settings.14,15

In addition to few studies of delayed ART initiation, there is little published operations research on programmatic trends and outcomes of HIV-infected patients enrolled in rural HIV treatment programs in Nigeria.5–,6,16 Lessons learned in rural settings may differ substantially from what has been learned in peri-urban and urban settings, thus providing valuable information to policymakers as service provision is scaled-up in secondary-level health facilities.16--18

This study reviewed baseline characteristics of adults enrolled in HIV care and treatment in an ART program in north-central Nigeria. Predictors of delayed initiation of ART, i.e., initiation of ART more than 90 days after enrollment into HIV care and treatment and trends in mortality and retention in care were also examined.

METHODS

Study design

This is an observational cohort study using patient-level data routinely collected for program monitoring and evaluation purposes.

Study setting

Since 2008, the Vanderbilt Institute for Global Health (VIGH) and its non-governmental Nigerian incorporated affiliate, Friends in Global Health, LLC (FGH), have been implementing comprehensive HIV/AIDS services focused in rural Kwara and Niger states, with funding from PEPFAR through the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Niger and Kwara states are located in Nigeria's north central region bordering the country of Benin on the west. The north central region has the highest HIV prevalence in the country (2010 adult HIV prevalence of 7.5% vs. national HIV prevalence of 3.6%).10 Both Ilorin, the capital of Kwara State and Minna, capital of Niger State are located on major highways that link the north and south of Nigeria, with substantial populations of HIV at-risk groups. The prevalence of HIV among adults in Niger and Kwara states is estimated to be 4.0% and 2.2%, respectively.19

As of mid 2011, VIGH/FGH supported HIV/AIDS services in five secondary-level facilities, namely: Sobi Specialist Hospital (Ilorin) and Lafiagi General Hospital in Kwara state; and Gawu Babangida Rural Hospital, Kuta Rural Hospital, and Umaru Yar Adua Hospital Sabon Wuse in Niger State. These five clinics are served by nine rural HTC/PMTCT feeder sites (`satellite' sites) in a hub and spoke model.

Study population

This study included all HIV-infected patients aged ≥15 years of both sexes entering HIV care and treatment in VU/FGH-supported treatment sites from June 1, 2009 through February 28, 2011. Study exclusion criteria included patients <15 years old and patients enrolled into care outside the defined study period.

Care and treatment protocol

VIGH/FGH-supported activities in Nigeria utilize an integrated and holistic health system strengthening approach, organized around two core principles: 1) direct technical assistance to government health facilities to implement integrated HIV clinical services at the state level; and 2) health workforce capacity development. Supported activities include the following program areas: adult and pediatric HIV care and treatment, prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT), HIV testing and counseling (HTC), tuberculosis (TB)-HIV services, orphans and vulnerable children, pharmaceutical logistics including procurement and provision of antiretroviral drugs, strengthening of laboratory infrastructure, and improvement of strategic information services.

Patients who tested HIV-positive in VIGH/FGH-supported clinics, or who were referred from other clinics, were enrolled into the HIV care and treatment program. HIV testing occurred in HTC, PMTCT or TB settings using the national serial rapid HIV testing algorithm. All enrolled patients received an initial evaluation, including baseline lab tests (CD4+ cell counts [CD4+ counts], hematology, chemistry), WHO clinical staging and a general clinical exam by a physician to screen for TB and other opportunistic infections. Clients received a basic care kit and other services, including adherence counseling, nutritional support, palliative care, and home-based care (based on need).

Enrolled adult patients were deemed eligible for ART based on Nigerian guidelines. Prior to June 2010, initiation guidelines included all patients with WHO stage I/II disease with CD4+ cells <200/μL, or with WHO stage III disease and CD4+ cells 200–350/ μL, or WHO stage IV disease regardless of CD4+ cell count. Beginning June 2010, initiation guidelines included having a CD4+ cell count <350/μL; or having WHO stage III or IV disease regardless of CD4+ cell count. The most commonly used adult ART regimen was a combination of zidovudine [ZDV] plus lamivudine [3TC] plus nevirapine [NVP] or efavirenz [EFV] (nonpregnant clients). Some clients received tenofovir [TDF] in place of ZDV and emtricitabine [FTC] instead of 3TC. Patients requiring second-line ART were placed on two new nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) plus the protease inhibitor lopinavir/ritonavir. Pregnant women with WHO stage III or IV disease and/or having a CD4+ cell count <350 cells/μL were immediately referred to treatment sites for ART initiation. Non-pregnant patients were followed up in clinic every 3 months. The specific care and treatment protocol for children is outside the scope of this study.

Data Source, Cleaning and Measurement

We used routinely collected PEPFAR program data for this analysis. The database was extracted on 31 May 2011 such that all patients enrolled on or before 28 February 2011 could contribute data for evaluation of ART initiation within 90 days of enrollment. After each clinic day, FGH data clerks entered data from national patient management and monitoring (PMM) forms that had been completed by clinicians, nurses, laboratory, and pharmacy staff into CAREWare™ (JPROG, New Orleans, LA), an electronic medical records system. Routine audits of medical records were performed to ensure that forms were completed accurately and laboratory data were entered correctly. Demographic information was based on self-report and included: sex, age, marital status, educational status, occupational status, and service entry into the program. Clinical and laboratory data included: weight, height, functional status, WHO clinical stage, TB status, CD4+ cell count, hepatitis B surface antigen and syphilis (VDRL) serology, pregnancy status, hematocrit, hemoglobin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and creatinine levels.

Data queries were generated for out-of-range and missing data. Each site addressed its data queries; clean data were extracted for the final analyses. We indicated the following out-of-range data for laboratory and anthropometric values as missing, based on consensus of our expert team of senior clinicians: hemoglobin <1 (n=46) and >18 (n=60); CD4+ cell count <0 (n=0) or >1500 (n=7); creatinine >100 mg/dL (n=10) or <0.1 mg/dL (n=0); height <100 cm (n=21) or >220 cm (n=4); weight <20 kg (n=23) or >120 kg (n=19). Extreme body mass index (BMI) records <10 kg/m2 (n=11) and >50 kg/m2 (n=38) were also considered out of range and therefore missing.

Definitions

Loss to follow-up (LTFU) was defined as those patients that are not deceased and have not had contact in 180 days prior to closure of the database; this definition adheres to the Nigeria and WHO policy standard of >90 days late for scheduled visit following a 3 month routine visit schedule.20,21 Patients who tested HIV-positive, received post-test counseling and had their information recorded in the clinic register were considered “enrolled into care”. Enrolled patients were considered to have `initiated' treatment once they were started on ART by a provider. Mortality was ascertained by facility records and tracking reports from home-based care and community health workers.21

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was ART initiation within 90 days of enrollment among those eligible for ART. The secondary endpoints included trends in rates of loss to follow up and mortality. We employed an “intent-to-continue treatment” approach for all analyses (disregarding subsequent changes to treatment, including treatment interruptions and terminations), such that this represents a best-case scenario.

Statistical analysis

To describe patients who fail to initiate ART among those eligible for ART we tabulated summary characteristics by ART initiation status within 90 days of enrollment. We used chi-square and Wilcoxon rank sum tests to examine differences in baseline characteristics by ART initiation status. We used a Kaplan-Meier plot and log-rank test to examine sex differences in timely ART initiation. A multivariable logistic regression model assessed whether baseline demographics, lab results, and clinical assessment were associated with delayed ART initiation among clients meeting national ART eligibility criteria at enrollment. To relax linearity assumptions, we modeled CD4+ counts and date of enrollment using restricted cubic splines. Multiple imputation was used to account for missing values of baseline predictors and to prevent case-wise deletion of missing data; 418 (36%) patients had complete data for all covariates. Covariates were identified a priori; those with more than 60% missing were excluded from multivariable analysis. We used the functions `aregImpute' and `fit.mult.impute' from the Hmisc package in R which used predictive mean matching to take random draws from imputation models; 25 imputation data sets were used in the analysis. Missing data is assumed to be missing at random conditional on the observed outcome and non-missing covariates; all variables used in the logistic regression outcome model were included in the imputation models. All hypothesis testing was two-sided with a level of significance set at 5%. We employed R-software 2.15.1 (www.r-project.org) for all data analyses. Analysis scripts are available at http://biostat.mc.vanderbilt.edu/ArchivedAnalyses

Ethical considerations

This study included retrospective analysis of routinely collected service data and did not involve any patient contact. Participants were not required to provide written informed consent. All personal identifiers were removed after data abstraction. Data personnel were trained on confidentiality and secure data transmission. Ethical approval was obtained from the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board and the Nigeria National Human Research Ethics Committee. Clearance from the Office of the Assistant Director of Science, CDC Atlanta was also obtained.

RESULTS

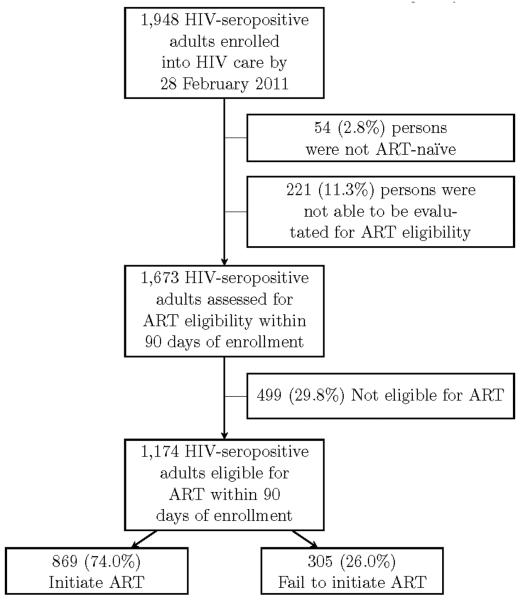

From June 1, 2009 to February 28, 2011 we enrolled 1,948 HIV-infected adult patients into care (Figure 1). Of the 1,673 HIV-infected adults assessed for ART eligibility within 90 days of enrollment, 1174 were deemed eligible. Of this number, 869 (74%) initiated ART within the first 90 days following enrollment.

Figure 1.

Flowchart depicting enrollment and ART eligibility for adult patients with HIV/AIDS, Kwara and Niger states of Nigeria, 2009–2011.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

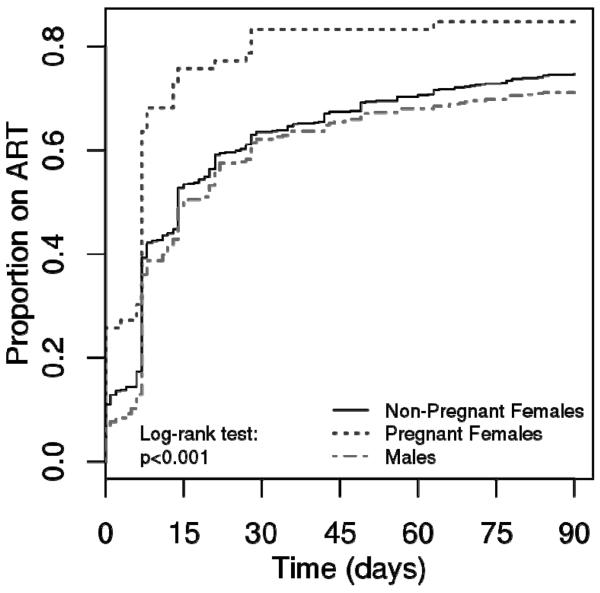

The majority of ART-eligible patients were female (62%).Slightly more than half of all ART-eligible patients were enrolled at Gawu Babangida Rural Hospital (58%) [Table 1]. The median age (interquartile range, IQR) of eligible patients was 34 years (28–40). Many ART-eligible patients were unemployed (55%) and illiterate (38%). Married persons comprised 78% of all ART eligible patients. We found 6% of women in the cohort (n=66) to be pregnant at enrollment. `Early' and `late/none' ART initiation groups were similar across age, sex, educational level and marital status. Pregnant females initiated ART within 90 days of enrollment at a more rapid rate than non-pregnant women and men (log rank test P<0.001, Figure 2).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of HIV-infected clients (age ≥15) by combination antiretroviral therapy initiation status at 5 rural sites in Kwara and Niger states of Nigeria, 2009–2011

| No ARTa | ART in 90 days | Combined | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=305) | (n=869) | (n=1174) | ||

| Clinic, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| GBRH | 132 (43.3%) | 545 (62.7%) | 677 (57.7%) | |

| Kuta | 42 (13.8%) | 22 (2.5%) | 64 (5.5%) | |

| LGH | 28 (9.2%) | 104 (12.0%) | 132 (11.2%) | |

| SBSH | 86 (28.2%) | 153 (17.6%) | 239 (20.4%) | |

| UMYMH | 17 (5.6%) | 45 (5.2%) | 62 (5.3%) | |

| Age (years)b | 34 (28, 42) | 34 (28, 40) | 34 (28, 40) | 0.3 |

| Female | 178 (58.4%) | 555 (63.9%) | 733 (62.4%) | 0.1 |

| Education, n (%) | 0.1 | |||

| None | 71 (33.2%) | 233 (40.3%) | 304 (38.4%) | |

| Started primary | 11 (5.1%) | 27 (4.7%) | 38 (4.8%) | |

| Completed primary | 35 (16.4%) | 77 (13.3%) | 112 (14.1%) | |

| Secondary | 56 (26.2%) | 149 (25.8%) | 205 (25.9%) | |

| Post secondary | 24 (11.2%) | 37 (6.4%) | 61 (7.7%) | |

| Qur'anic | 17 (7.9%) | 55 (9.5%) | 72 (9.1%) | |

| Missingc | 91 (29.8%) | 291 (33.5%) | 382 (32.5%) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.3 | |||

| Divorced | 6 (2.6%) | 13 (2.2%) | 19 (2.3%) | |

| Married | 174 (74.4%) | 474 (79.3%) | 648 (77.9%) | |

| Separated | 8 (3.4%) | 29 (4.8%) | 37 (4.4%) | |

| Single | 22 (9.4%) | 37 (6.2%) | 59 (7.1%) | |

| Widowed | 24 (10.3%) | 45 (7.5%) | 69 (8.3%) | |

| Missingc | 71 (23.3%) | 271 (31.2%) | 342 (29.1%) | |

| Occupation, n (%) | 0.01 | |||

| Employed | 75 (32.6%) | 151 (25.9%) | 226 (27.8%) | |

| Other | 23 (10.0%) | 90 (15.4%) | 113 (13.9%) | |

| Retired | 4 (1.7%) | 2 (0.3%) | 6 (0.7%) | |

| Student | 9 (3.9%) | 13 (2.2%) | 22 (2.7%) | |

| Unemployed | 119 (51.7%) | 327 (56.1%) | 446 (54.9%) | |

| Missingc | 75 (24.6%) | 286 (32.9%) | 361 (30.7%) | |

| Referral type, n (%) | 0.054 | |||

| In-patient | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) | |

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.5%) | 2 (0.3%) | |

| PMTCT | 5 (3.2%) | 34 (8.1%) | 39 (6.8%) | |

| VCT | 148 (96.1%) | 383 (91.4%) | 531 (92.7%) | |

| Missingc | 151 (49.5%) | 450 (51.8%) | 601 (51.2%) | |

| Pregnant (enrollment) | 10 (3.3%) | 56 (6.4%) | 66 (5.6%) | 0.055 |

GBRH: Gawu Babangida Rural Hospital; LGH: Lafiagi General Hospital; SBSH: Sobi Specialist Hospital; UMYMH: Umaru Yar'adua Memorial Hospital. ART: combination antiretroviral therapy. PMTCT: prevention of mother to child HIV transmission. VCT: voluntary counseling and testing.

Includes 256 patients not initiating treatment prior to database cut date, and 49 initiating >90 days from enrollment.

Continuous variables are reported as medians (interquartile range).

Percentages are computed using the number of patients with a non-missing value.

Figure 2.

Combination antiretroviral therapy initiation during the first 90 days post-enrollment, Kwara and Niger states of Nigeria, 2009–2011.

Clinical characteristics of the cohort are shown in Table 2. Median CD4+ cell count at enrollment were 156/μL (IQR: 81–257). Median CD4+ cell counts and hemoglobin levels were similar between early and late/none ART status categories. The median (IQR) values for CD4+ cell counts and hemoglobin were 149/μL (69–282) and 10.2 g/dL (8.8–11.8), respectively, for eligible patients who did not initiate ART within 90 days of enrollment. Two-thirds of all patients (67%) had advanced HIV disease at enrollment (WHO stage III or IV disease). Clients who did not initiate ART within 90 days were more likely to present with severe clinical illness than those who did (proportion of delayed ART initiators with WHO stage IV disease = 8% vs. 4% of early initiators, P<0.01).

Table 2.

Distribution of clinical characteristics by combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation among HIV/AIDS patients eligible to start therapy, Kwara and Niger states of Nigeria, 2009–2011.

| No ARTa | ART in 90 days | Combined | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=305) | (n=869) | (n=1174) | ||

| Height (cm)b | 162 (156, 169) | 162 (156, 167) | 162 (156, 167) | 0.6 |

| Missing, n (%)c | 110 (36.1%) | 197 (22.7%) | 307 (26.1%) | |

| Weight (kg)b | 51 (45, 60) | 53 (47, 60) | 52 (46, 60) | 0.06 |

| Missing, n (%)c | 38 (12.5%) | 25 (2.9%) | 63 (5.4%) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)b | 19.3 (17.1, 21.9) | 20.3 (18.3, 22.5) | 20.1 (18.1, 22.4) | 0.001 |

| Missing, n (%)c | 114 (37.4%) | 201 (23.1%) | 315 (26.8%) | |

| Functional status, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Bedridden | 14 (4.8%) | 13 (1.5%) | 27 (2.3%) | |

| Ambulatory | 39 (13.4%) | 72 (8.3%) | 111 (9.6%) | |

| Working | 237 (81.7%) | 778 (90.2%) | 1015 (88.0%) | |

| Missingc | 15 (4.9%) | 6 (0.7%) | 21 (1.8%) | |

| CD4+ count (cells/μL)*b | 149 (69, 282) | 159 (86, 250) | 156 (81, 257) | 0.9 |

| CD4+ count category, n (%) | ||||

| ≤50/μL | 45 (18.2%) | 99 (11.9%) | 144 (13.4%) | |

| 51–200 | 104 (42.1%) | 430 (51.8%) | 534 (49.6%) | |

| 201–350 | 71 (28.7%) | 243 (29.3%) | 314 (29.2%) | |

| >350 | 27 (10.9%) | 58 (7.0%) | 85 (7.9%) | |

| Missingc | 58 (19.0%) | 39 (4.5%) | 97 (8.3%) | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL)b | 10.2 (8.8, 11.8) | 10.3 (9, 11.7) | 10.2 (9, 11.7) | 0.6 |

| Hemoglobin category, n(%) | ||||

| <8 g/dL | 31 (15.7%) | 98 (12.6%) | 129 (13.3%) | |

| 8–10 g/dL | 63 (32.0%) | 248 (32.0%) | 311 (32.0%) | |

| >10 g/dL | 103 (52.3%) | 430 (55.4%) | 533 (54.8%) | |

| Missing | 108 (35.4%) | 93 (10.7%) | 201 (17.1%) | |

| Creatinine (mg/dL)b | 0.8 (0.6, 1.2) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) | 0.7 |

| Missing, n (%)c | 186 (61.0%) | 596 (68.6%) | 782 (66.6%) | |

| WHO clinical stage, n (%) | 0.003 | |||

| I | 37 (12.6%) | 162 (18.7%) | 199 (17.2%) | |

| II | 39 (13.3%) | 140 (16.2%) | 179 (15.4%) | |

| III | 194 (66.0%) | 527 (60.9%) | 721 (62.2%) | |

| IV | 24 (8.2%) | 36 (4.2%) | 60 (5.2%) | |

| Missingc | 11 (3.6%) | 4 (0.5%) | 15 (1.3%) | |

| 1-year mortalityd | 21 (6.9%) | 25 (2.9%) | 46 (3.9%) | 0.003 |

| 1-year loss to follow upd | 119 (39.0%) | 249 (28.7%) | 368 (31.3%) | 0.001 |

WHO = The World Health Organization.

Includes 256 patients not initiating treatment prior to database cut date, and 49 initiating >90 days from enrollment.

Continuous variables are reported as medians (interquartile range).

Percentages are computed using the number of patients with a non-missing value.

Mortality and loss to follow up are at 1 year post-enrollment.

Predictors of ART initiation

Table 3 shows logistic regression results for demographic and clinical predictors of delayed ART initiation in all treatment eligible patients (including pregnant women). Clinic of enrollment and time of enrollment were strongly predictive of delayed ART initiation (p<0.001). In general, patients enrolled at a more recent period were more likely to have delayed ART initiation beyond 90 days of enrollment than those enrolled at the beginning of the project (December 2010 vs. June 2009, OR=2.13 [95%CI: 1.19–3.81]). Patients who were less functionally active were more likely to delay initiating treatment; bedridden clients had a 4-fold odds of delayed treatment initiation compared with their counterparts who were still working at the time of enrollment (OR: 4.17, 95% CI: 1.63–10.7). Lower BMI and higher CD4+ counts were also independent predictors of delayed ART initiation. For every unit increase in BMI, we observed a 7% decrease in odds of delayed ART, such that an individual with BMI of 18.5 vs. 25 kg/m2 has 63% higher odds of delayed initiation (OR: 1.63, 95% CI: 1.13–2.34). The relationship between CD4+ cell count and log-odds of delayed infection was U-shaped with a trough at 165 cells/ μL - patients having advanced (CD4+ cell count <50/μL) and moderate levels of immunosuppression (about 250 cells/ μL) at the time of enrollment had equal probability of delayed initiation. A HIV-infected patient with CD4+ cell count of 350/μL had half the odds of delayed treatment than a patient having a CD4+ cell count of 200/μL (OR: 2.10, 95% CI: 1.31–3.35). We found no evidence of an independent association between WHO stage and treatment initiation. Associations remained unchanged after pregnant women were excluded from the analysis (data not shown).

Table 3.

Logistic regression model: Failure to initiate combination antiretroviral therapy in 90 days among eligible patients, Kwara and Niger states of Nigeria, 2009–2011 (n=1174).

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Clinic | |

| GBRH (ref) | 1 |

| Kuta | 5.70 (2.99, 10.89) |

| LGH | 1.45 (0.86, 2.46) |

| SBSH | 2.46 (1.58, 3.85) |

| UMYMH | 0.84 (0.40, 1.76) |

| Age (per 5 yrs) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.09) |

| Sex and pregnancy | |

| Female (ref) | 1 |

| Pregnant Female | 0.65 (0.31, 1.38) |

| Male | 1.32 (0.94, 1.87) |

| Education | |

| None (ref) | 1 |

| Started primary | 1.29 (0.59, 2.81) |

| Completed primary | 1.56 (0.91, 2.68) |

| Secondary | 1.43 (0.88, 2.33) |

| Post secondary | 2.08 (1.03, 4.20) |

| Qur'anic | 1.11 (0.58, 2.12) |

| Marital status | |

| Married (ref) | 1 |

| Divorced | 1.25 (0.43, 3.66) |

| Separated | 0.79 (0.33, 1.88) |

| Single | 1.31 (0.68, 2.54) |

| Widowed | 1.36 (0.78, 2.39) |

| Occupation | |

| Employed (ref) | 1 |

| Other | 0.98 (0.52, 1.82) |

| Student | 1.71 (0.61, 4.81) |

| Unemployed | 1.08 (0.66, 1.76) |

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2) | 0.93 (0.88, 0.98) |

| Functional status | |

| Working (ref) | 1 |

| Ambulatory | 1.92 (1.15, 3.18) |

| Bedridden | 4.17 (1.63, 10.67) |

| CD4+ cell count (cells/μL) | |

| 50 vs. 200 | 1.49 (0.93, 2.39) |

| 350 vs. 200 | 2.10 (1.31, 3.35) |

| 500 vs. 200 | 3.02 (1.69, 5.39) |

| Hemoglobin (per 1 g/dL) | 1.00 (0.91, 1.10) |

| WHO clinical stage | |

| I (ref) | 1 |

| II | 1.05 (0.60, 1.82) |

| III | 1.12 (0.70, 1.81) |

| IV | 1.16 (0.50, 2.71) |

| Month of enrollment | |

| June 2009 (ref) | 1 |

| December 2009 | 1.01 (0.68, 1.48) |

| June 2010 | 1.18 (0.64, 2.19) |

| December 2010 | 2.13 (1.19, 3.81) |

There is evidence that the association between the log-odds of delayed HAART initiation is non-linear with CD4+ count (p=0.021) and date of enrollment (p=0.082). The last day of the month (e.g. June 30) is used to summarize odds ratios for month of enrollment.

There are 1174 patients included in this model. Missing values of baseline predictors are accounted for using multiple imputation.

GBRH: Gawu Babangida Rural Hospital; LGH: Lafiagi General Hospital; SBSH: Sobi Specialist Hospital; UMYMH: Umaru Yar'adua Memorial Hospital.

Retention and Mortality

More than one-third of patients (39%) enrolled into the program and not initiating treatment within 90 days were LTFU in 12 months; 49% of this LTFU occurred after the first visit. The proportion of clients deemed LTFU was larger among delayed initiators than among those who commenced ART within 90 days of enrollment (39% vs. 29% respectively, P<0.01). Approximately 7% of patients who did not initiate treatment within 90 days were confirmed deceased within 1 year of enrollment (versus 3% of those who started ART, P<0.001).

DISCUSSION

Our experience in Nigeria indicates the feasibility of successfully implementing and rapidly scaling up treatment services in rural north central Nigeria. However, outcomes are sub-optimal. Prior to 2008, there was no ART-based HIV care at these sites. A sizeable proportion of our patients were found to have advanced disease (WHO stage III/IV) at enrollment, a finding that suggests that testing and linkage is not well implemented at the community level. However, the proportion of patients having very advanced clinical disease (WHO stage IV) showed a progressive decrease with program maturation, an encouraging sign that we are accessing patients earlier who have less advanced disease.

We found a preponderance of females and unemployed persons among our patient cohort, many of whom were also illiterate. The demographic characteristics of the clients in our program reflect the sociocultural milieu of these communities. The rural northern part of Nigeria has lower educational attainment and higher poverty rates than the southern part of the country.22 Women and girls comprise 60% of people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa; in Nigeria an estimated 1.7 million women over the age of 15 are HIV infected.2 It is therefore not surprising that we have more women than men in our program; as seen in Nigeria and elsewhere, PMTCT is a bridge for women to link to their own chronic HIV care needs.16,23–26 Novel approaches to recruit more men into testing and care are needed.14,27–29

There are few studies evaluating retention and clinical outcomes (including LTFU and mortality) from Nigeria.5,6,16,21 We found substantial LTFU rates among our patients (33% by 12 months post enrollment), higher among clients who did not initiate treatment within 90 days of enrollment (39% at 12 months). A possible contributor to our high LTFU rates is our non-utilization of pharmacy data to ascertain LTFU. Some clients could have picked up their medications without having a clinical encounter, thereby erroneously becoming classified as LTFU. We think this unlikely due to the dearth of alternative sources of medications in these rural areas. We note similarly reported high rates of LTFU at 12 months in such diverse venues as large urban facilities in Abuja (34%),30 Benin, Calabar, Enugu and Kano (25%)24 and rural/urban Southeast Nigeria (30%).23 There is a need for well-designed HIV treatment retention and attrition studies in Nigeria that will provide valid estimates for LTFU and other outcomes.6 We also need field surveys of LTFU clients; such surveys in Uganda have been helpful in determining which LTFU are alive in care elsewhere, alive but not in care, and deceased.31 A uniform definition for LTFU would be helpful for PEPFAR, the Global Fund to fight HIV, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and other Nigerian programs to permit performance to be compared fairly across in-country treatment programs.32,33 However, different LTFU definitions may have to be used for different purposes.34

We believe that certain program structural features help explain missing data. The first visit was the only visit that took place in half of LTFU cases who were enrolled and did not initiate treatment within 90 days (i.e., half of patients eligible for ART who were LTFU never showed up for their second visit). CD4+ results are often provided to the patient at the second visit; therefore a sizeable proportion of our eligible clients would not have known that they were eligible for ART. Point-of-care CD4+ testing in rural sites may help to address this awareness gap and reduce early attrition.35,36 Our programs should also consider early patient tracking and adherence efforts to be important for all patients, not merely those who have initiated ART. The aforementioned Abuja study made a similar case for early tracing of defaulters, since two-thirds of documented deaths in their cohort occurred within 3 months of enrollment.23

Our finding that death was more likely to occur in late treatment initiators than among patients started on ART within 90 days of enrollment is expected.37–39 Two thirds of our clients (67%) had advanced HIV disease (WHO stage III or IV) at the time of enrollment. Reports that the majority of deaths in treatment programs occur in the months immediately following ART initiation are well-documented.40–42 We cannot confirm this in this study, as our mortality numbers are small, yielding unstable estimates.

Factors that were independently associated with delayed ART initiation in this study included: more recent period of enrollment, clinic, lower function/higher disability status, lower BMI and higher CD4+ cell counts. Unfortunately, as our treatment program matured, newly enrolled patients were less and less likely to be initiated on ART. The higher risk of delayed ART initiation as our program matured could be due to at least two factors. First, we underwent significant changes in program leadership in the second year of the program which reduced the intensity of staff supervision and mentoring as well as logistics coordination (specifically laboratory [CD4+ cell count, chemistry, and hematology/CBC draws] and pharmacy [ART medication stocks] issues). Second, we transitioned experienced FGH clinicians from direct patient care responsibilities to technical assistance in the second year of program implementation, which resulted in less experienced clinicians taking on more direct patient care. These changes could have cumulatively affected the quality of services provided, including ART-related decision-making and early tracking of newly-enrolled patients. Since 91% of timely initiators had high functional status versus 82% of late initiators, we confirm that the sickest patients are not necessarily those going on ART at the highest rates in rural north central Nigeria. A reason could be the delay in commencing ART that is sometimes associated with the need to first provide nutritional supplementation in markedly ill-looking or malnourished patients or with the clinicians' inclinations to wait until treatment for TB and other OIs is commenced. Clients at Gawu Babangida Rural Hospital were more likely to be initiated on ART; it was our first treatment center in Niger state and is readily accessible to FGH staff in Abuja, facilitating closer oversight and easier access to lab and pharmacy resources. In contrast, our most remote treatment site (Kuta hospital) had the worst outcomes.

This study, grounded in real-world data, has several limitations. We had substantial amounts of missing data, especially for core sociodemographic variables. We were also unable to determine eligibility for patients missing CD4+ cell counts with WHO stage I and II disease (and III before June 2010), whereas this determination was straightforward for patients having WHO stage IV disease (and III after June 2010) who were all eligible for treatment. Since those patients without CD4+ counts were not included in the denominator, the proportion of patients we report as ART eligible could be an overestimate. The mortality statistics presented here are an underestimate, as some LTFU patients are deceased. A major strength of this study is our use of multiple clinics in real-world, rural Nigeria, reflecting the realities of PEPFAR implementation for a rural, under-studied population. Other strong points include: large sample size, use of an extensive querying and data cleaning process and the application of multiple imputation to account for missing values of baseline predictors and to prevent case-wise deletion of missing data.

In summary, we report suboptimal findings from the first two years of a comprehensive HIV treatment program in rural north central Nigeria. Knowledge that less immunosuppression, lower functional status, clinic of attendance, and more recent date of enrollment were significantly associated with delayed ART initiation gives us specific targets for quality improvement efforts. Community-based initiatives targeting at-risk malnourished patients, many of whom also have reduced functional status, appear to be needed in such settings.43–45 As PEPFAR moves from the emergency to the consolidation phase, with an increasing proportion of scale-up activities occurring in rural settings, it becomes even more important to employ program data in assessing performance and determining what changes can be implemented that would make services more efficient, effective and sustainable by local host governments in such settings.46

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the contributions of the following persons to the implementation of Vanderbilt's HIV program in Nigeria: Julie Lankford (Director, Global Operations, VIGH), Robb Reed (former Chief of Party, FGH Nigeria), Dr. Saidu Saadu (Director, Clinical Services, FGH Nigeria), Dr. Anthony Okwuosah (former Activity Manager, CDC-Nigeria) and Subrat Das (Project Officer, CDC-Nigeria).

This publication was made possible by support from the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through cooperative agreement No. 5U2GPS001063 from the HHS/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Global HIV/AIDS and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health, award number R01HD075075. Support was also received from the Fogarty Clinical Research Fellows Program at Vanderbilt, NIH award number R24TW007988. The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.UNGASS [Accessed 02/28/2012];UNGASS Country Progress Report: Nigeria. 2010 http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/monitoringcountryprogress/2010progressreportssubmittedbycountries/Nigeria_UNGASS_2010_Final_Country_Report_20110604.pdf.

- 2.UNAIDS . Global report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2010. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; New York: 2010. [Accessed 03/08/2012]. http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/Global_report.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF . Progress report 2011. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2011. [Accessed 03/01/12]. Global HIV/AIDS response: Epidemic update and health services progress toward universal access. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241502986_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Agency for the Control of AIDS (NACA) Country Progress Report, Nigeria, GARPR 2012. Abuja: 2012. [Accessed 09/01/12]. Federal Republic of Nigeria Global AIDS Response. http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/knowyourresponse/countryprogressreports/2012countries/Nigeria%202012%20GARPR%20Report%20Revised.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Agency for the Control of AIDS (NACA) Research and New Technologies. NACA; Abuja: 2009. [Accessed 10/01/12]. National HIV/AIDS Policy Review Report. http://naca.gov.ng/index2.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&gid=67&Itemid=268. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aliyu MH, Varkey P, Salihu HM, et al. The HIV/AIDS epidemic in Nigeria: progress, problems and prospects. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2010;39:233–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myer L, Zulliger R, Pienaar D. Diversity of patient preparation activities before initiation of antiretroviral therapy in Cape Town, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17:972–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myer L, Zulliger R, Bekker LG, Abrams E. Systemic delays in the initiation of antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy do not improve outcomes of HIV-positive mothers: a cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gebrekristos HT, Mlisana KP, Karim QA. Patients' readiness to start highly active antiretroviral treatment for HIV. BMJ. 2005;331:772–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7519.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tayler-Smith K, Zachariah R, Manzi M, et al. Demographic characteristics and opportunistic diseases associated with attrition during preparation for antiretroviral therapy in primary health centres in Kibera, Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16:579–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawn SD, Myer L, Orrell C, Bekker LG, Wood R. Early mortality among adults accessing a community-based antiretroviral service in South Africa: implications for programme design. AIDS. 2005;19:2141–2148. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000194802.89540.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Violari A, Cotton MF, Gibb DM, et al. CHER Study Team. Early antiretroviral therapy and mortality among HIV-infected infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2233–2244. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdool Karim SS, Naidoo K, Grobler A, et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral drugs during tuberculosis therapy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:697–706. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braitstein P, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, et al. Antiretroviral Therapy in Lower Income Countries (ART-LINC) Collaboration; ART Cohort Collaboration (ART-CC) groups. Mortality of HIV-1-infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high-income countries. Lancet. 2006;367:817–824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawn SD, Harries AD, Anglaret X, Myer L, Wood R. Early mortality among adults accessing antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:1897–1908. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830007cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Odafe S, Idoko O, Badru T, et al. Patients' demographic and clinical characteristics and level of care associated with lost to follow-up and mortality in adult patients on first-line ART in Nigerian hospitals. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15:17424. doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.2.17424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bajunirwe F, Muzoora M. Barriers to the implementation of programs for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: a cross-sectional survey in rural and urban Uganda. AIDS Res Ther. 2005;2:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aliyu HB, Chuku NN, Kola-Jebutu A, et al. What Is the Cost of Providing Outpatient HIV Counseling and Testing and Antiretroviral Therapy Services in Selected Public Health Facilities in Nigeria? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61:221–225. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182683b04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Federal Ministry of Health, Nigeria (FMOH) 2010 National HIV Sero-prevalence Sentinel Survey. Federal Ministry of Health; Abuja: 2010. National AIDS/STI Control Program. Technical Report. Available at: http://www.nigeria-aids.org/documents/2010_National%20HIV%20Sero%20Prevalence%20Sentinel%20Survey.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization (WHO) HIV/AIDS . Patient monitoring guidelines for HIV care and antiretroviral therapy (ART) WHO Press; Geneva: 2006. pp. 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Odafe S, Torpey K, Khamofu H, et al. The pattern of attrition from an antiretroviral treatment program in Nigeria. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Omonona BT. Quantitative Analysis of Rural Poverty in Nigeria. Nigeria Strategy Support Programme (NSSP) Background Paper 9; Washington D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute; 2009. Available at: http://www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/publications/nssppb17.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onoka CA, Uzochukwu BS, Onwujekwe OE, et al. Retention and loss to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programmes in southeast Nigeria. Pathog Glob Health. 2012;106:46–54. doi: 10.1179/2047773211Y.0000000018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charurat M, Oyegunle M, Benjamin R, et al. Patient retention and adherence to antiretrovirals in a large antiretroviral therapy program in Nigeria: a longitudinal analysis for risk factors. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tonwe-Gold B, Ekouevi DK, Viho I, et al. Antiretroviral treatment and prevention of peripartum and postnatal HIV transmission in West Africa: evaluation of a two-tiered approach. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sturt AS, Dokubo EK, Sint TT. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) for treating HIV infection in ART-eligible pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3:CD008440. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iliyasu Z, Abubakar IS, Kabir M, et al. Knowledge of HIV/AIDS and attitude towards voluntary counseling and testing among adults. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:1917–1922. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nwachukwu CE, Odimegwu C. Regional patterns and correlates of HIV voluntary counselling and testing among youths in Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2011;15:131–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stephenson R, Miriam Elfstrom K, Winter A. Community Influences on Married Men's Uptake of HIV Testing in Eight African Countries. AIDS Behav. 2012 Jun 8; doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0223-0. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ugbena R, Aberle-Grasse J, Diallo K, et al. Virological response and HIV drug resistance 12 months after antiretroviral therapy initiation at 2 clinics in Nigeria. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:S375–80. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geng EH, Bangsberg DR, Musinguzi N, et al. Understanding reasons for and outcomes of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral therapy programs in Africa through a sampling-based approach. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:405–411. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b843f0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chi BH, Yiannoutsos CT, Westfall AO, et al. Universal definition of loss to follow-up in HIV treatment programs: a statistical analysis of 111 facilities in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosen S, Fox MP. Retention in HIV care between testing and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shepherd BE, Blevins M, Vaz LM, Moon TD, José E, Gonçalves F, Vermund SH. Impact of definitions of loss to follow-up on estimates of retention, mortality, and disease progression: Application to an HIV program in Mozambique. Am J Epidemiol. 2013 doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt030. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jani IV, Sitoe NE, Alfai ER, et al. Effect of point-of-care CD4 cell count tests on retention of patients and rates of antiretroviral therapy initiation in primary health clinics: an observational cohort study. Lancet. 2011;378:1572–1579. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shepherd BE, Blevins M, Vaz LM, Moon TD, José E, Gonçalves F, Vermund SH. Impact of definitions of loss to follow-up on estimates of retention, mortality, and disease progression: Application to an HIV program in Mozambique. Am J Epidemiol. 2013 doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt030. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zachariah R, Reid SD, Chaillet P, et al. Viewpoint: Why do we need a point-of-care CD4 test for low-income countries? Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16:37–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.HIV Trialists' Collaborative Group Zidovudine, didanosine, and zalcitabine in the treatment of HIV infection: meta-analyses of the randomised evidence. Lancet. 1999;353:2014–2025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hammer SM, Squires KE, Hughes MD, et al. A controlled trial of two nucleoside analogues plus indinavir in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection and CD4 cell counts of 200 per cubic millimeter or less. AIDS Clinical Trials Group 320 Study Team. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:725–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zolopa A, Andersen J, Powderly W, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy reduces AIDS progression/death in individuals with acute opportunistic infections: a multicenter randomized strategy trial. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coetzee D, Hildebrand K, Boulle A, et al. Outcomes after two years of providing antiretroviral treatment in Khayelitsha, South Africa. AIDS. 2004;18:887–895. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200404090-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferradini L, Jeannin A, Pinoges L, et al. Scaling up of highly active antiretroviral therapy in a rural district of Malawi: an effectiveness assessment. Lancet. 2006;367:1335–1342. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68580-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stringer JS, Zulu I, Levy J, et al. Rapid scale-up of antiretroviral therapy at primary care sites in Zambia: feasibility and early outcomes. JAMA. 2006;296:782–793. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koethe JR, Blevins M, Bosire C, et al. Self-reported dietary intake and appetite predict early treatment outcome among low-BMI adults initiating HIV treatment in sub-Saharan Africa. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16:549–58. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012002960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koethe JR, Limbada MI, Giganti MJ, et al. Early immunologic response and subsequent survival among malnourished adults receiving antiretroviral therapy in Urban Zambia. AIDS. 2010;24:2117–21. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833b784a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koethe JR, Lukusa A, Giganti MJ, Chi BH, Nyirenda CK, Limbada MI, Banda Y, Stringer JS. Association between weight gain and clinical outcomes among malnourished adults initiating antiretroviral therapy in Lusaka, Zambia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:507–13. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b32baf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vermund SH, Sidat M, Weil LF, Tique JA, Moon TD, Ciampa PJ. Transitioning HIV care and treatment programs in southern Africa to full local management. AIDS. 2012;26:1303–10. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283552185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]