Abstract

Cells operate a signaling network termed unfolded protein response (UPR) to monitor protein-folding capacity in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). IRE1 is an ER transmembrane sensor that activates UPR to maintain ER and cellular function. While mammalian IRE1 promotes cell survive, it can initiate apoptosis via decay of anti-apoptotic microRNAs. Convergent and divergent IRE1 characteristics between plants and animals underscore its significance in cellular homeostasis. This review provides an updated scenario of IRE1 signaling model, discusses emerging IRE1 sensing mechanisms, compares IRE1 features among species, and outlines exciting future directions in UPR research.

Keywords: unfolded protein response, ER stress, IRE1, cell fate, protein quality control, membrane trafficking system

ER stress and unfolded protein response

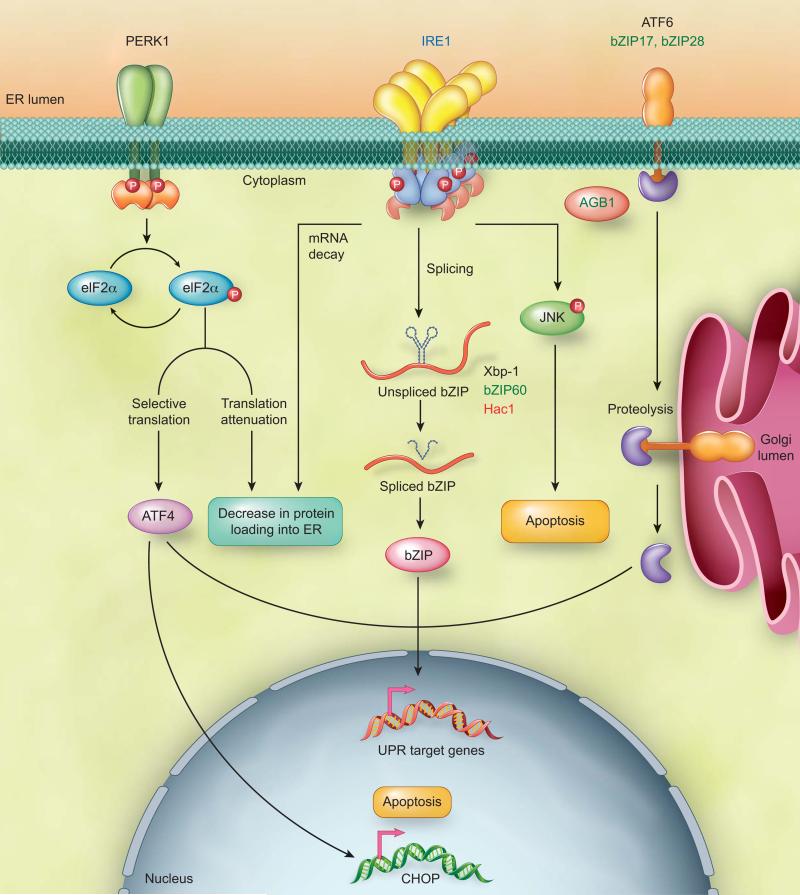

The membrane trafficking system maintains operation of approximately one-third of the eukaryotic proteome. Most secretory proteins first enter the ER for folding and assembly. To maintain the fidelity of ER functions, cells coordinate a protein quality control system with a signaling network termed unfolded protein response (UPR) [1-6]. UPR is triggered by ER transmembrane sensors upon ER stress, a cellular condition referring to the accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER (Figure 1) [7, 8]. The adaptive response occurring at the initial phase of UPR aims to rebalance the protein-folding homeostasis [2, 3, 9-12]. If cells fail to recover from ER stress, UPR represses the adaptive response and triggers apoptosis [1, 3, 4, 7, 13, 14]. The inositol-requiring enzyme (IRE1) is the only identified ER stress sensor in yeast and essential for UPR in animals and plants [15-18] (Figure 1). As an ER transmembrane protein, IRE1 monitors ER homeostasis through an ER luminal stress-sensing domain and triggers UPR through a cytoplasmic kinase domain and an RNase domain [15, 16]. Upon ER stress, IRE1 RNase is activated through conformational change, autophosphorylation, and higher order oligomerization [19-21]. Mammalian IRE1 initiates diverse downstream signaling of the UPR either through unconventional splicing of the transcription factor Xbp-1 or and through posttranscriptional modifications via Regulated IRE1-Dependent Decay (RIDD) of multiple substrates [15, 16, 22-25]. In addition, PERK and ATF6 function as two distinct mammalian ER stress sensors to cope with complex UPR scenarios [7, 26] (Figure 1). Similar to IRE1, PERK and ATF6 are ER transmembrane proteins that contain an ER luminal stress-sensing domain and a cytoplasmic enzymatic domain. To prevent a further increase in protein-folding demand in the ER, PERK transiently inhibits general protein translation through phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (elF2α). Phosphorylated elF2α can also selectively activate translation of mRNAs including ATF4 transcription factor to regulate UPR target genes [27]. ER stress triggers relocation of ATF6 from the ER to the Golgi where it undergoes proteolytic cleavage. The cleaved transcription factor domain of ATF6 enters the nucleus for UPR regulation [28-30] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Overview of UPR arms in eukaryotes.

The IRE1 arm is conserved in eukaryotes. IRE1 unconventionally splices bZIP transcription factors, Xbp-1, bZIP60, and Hac1 mRNA in mammals, plants, and yeast respectively. The spliced bZIP transcription factor enters into the nucleus to regulate UPR target genes. In addition, two distinct arms mediated by PERK and ATF6 regulate mammalian UPR. ATF6 is an ER transmembrane transcription factor. ER stress triggers the relocation of ATF6 from the ER to the Golgi apparatus where it is undergone proteolytic cleavage. Subsequently, the transcription factor domain of ATF6 enters into the nucleus to modulate transcription of UPR target genes. Two functional homologues of ATF6, bZIP17 and bZIP28, exist in plants. PERK, an ER transmembrane protein kinase is identified only in animals. Upon ER stress, PERK phosphorylates eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (elF2α), which leads to a transient inhibition of general protein translation and selective translation of the transcription factor ATF4. Under irremediable ER stress, PERK-elF2α-ATF4-CHOP and IRE1-JNK initiate apoptosis in mammals. Moreover, the beta subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein complex, AGB1, is essential for the plant UPR. Although the G protein complex is conserved in eukaryotes, its significance in UPR is unclear in other eukaryotic organisms. Color code: blue - eukaryotes; black - mammals; green - plants; red - yeast.

The main molecular mechanisms underlying IRE1 unconventional splicing are conserved in eukaryotes. In budding yeast, mammals, and plants, there is only one transcription factor identified as a splicing target of IRE1 (Figure 1). The stem-loop structure and cleavage site of the IRE1 splicing substrate are conserved among species. In contrast, RIDD appears more divergent in eukaryotes. In yeast, RIDD is only operated in fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, but not in budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae [31]. Intriguingly, RIDD-mediated decrease in protein-folding demand is the only identified mechanism of UPR in fission yeast [31]. While plant RIDD may potentially degrade a significant portion of mRNAs encoding secretory proteins [32], it is undetermined whether plant RIDD processes various substrates to direct UPR outputs like mammalian RIDD. Unlike mammalian UPR, plant PERK orthologs have not been yet identified; however, two functional homologs of ATF6, bZIP28 and bZIP17, exist in plants [33] (Figure 1). Moreover, a component of G-protein complex, AGB1, is essential for plant UPR [17] while an alternative G-protein-coupled receptor is involved in noncanonical UPR in C.elegans [34]. Due to large members of the mammalian G-protein complex, its roles in classical UPR might be more challenging to reveal. While IRE1 and ATF6 arms are partially conserved between plants and animals, it is interesting to establish the degree of UPR diversification between the two species.

This review presents the latest advances and viewpoints on IRE1-dependent UPR research. We focus on the recent groundbreaking discoveries that define IRE1 as a master regulator in cell fate determination under ER stress. IRE1 was long considered as a positive regulator in cell survival. Thus, the repression of IRE1 was believed to potentiate apoptosis. The recent identification of novel IRE1 regulatory events reveals that IRE1 signaling is persistent during ER stress. Namely, IRE1 can no longer be considered simply as a driving force for cell survival, but rather as an administrator/executor of cell fate determination under ER stress. Through presentation of the recent evidence establishing that IRE1 triggers diverse signaling, we delineate current IRE1-signaling models. It has also become clear that IRE1 monitors cellular homeostasis beyond the protein-folding status in the ER; therefore, the functional relevance of the UPR within physiological processes will be discussed. Finally, we will compare convergent and divergent features of IRE1 between plants and mammals to provide an integrated view of IRE1 in multicellular eukaryotes.

IRE1 signaling in cell fate determination

Life-versus-death determination is constantly scrutinized and tightly controlled. Prevalence of malfunctioning cells due to irremediable ER stress contributes to significant diseases, including cancer and diabetes. Conversely, over-commitment to cell death may result in organ damage or cell degenerative diseases [35-39]. To reach optimal fitness under ER stress, cell fates are determined through tight coordination of adaptive and apoptotic responses [37, 40, 41]. In mammals, PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 regulates the transcription factor CHOP to activate ER stress-triggered apoptosis. In parallel, IRE1 controls cell fate determination through mitogen protein kinase JNK under ER stress [3, 7, 8, 42] (Figure 1). In contrast, while ER stress can play a role in programmed cell death in plants [43], very little is known about ER stress-induced cell death in plants [17, 32, 44]. Furthermore, lack of sequence homologs of most mammalian apoptosis regulators in plants hints that divergent mechanisms of ER stress-induced cell death exist among organisms.

Revised model of IRE1α signaling network in mammals

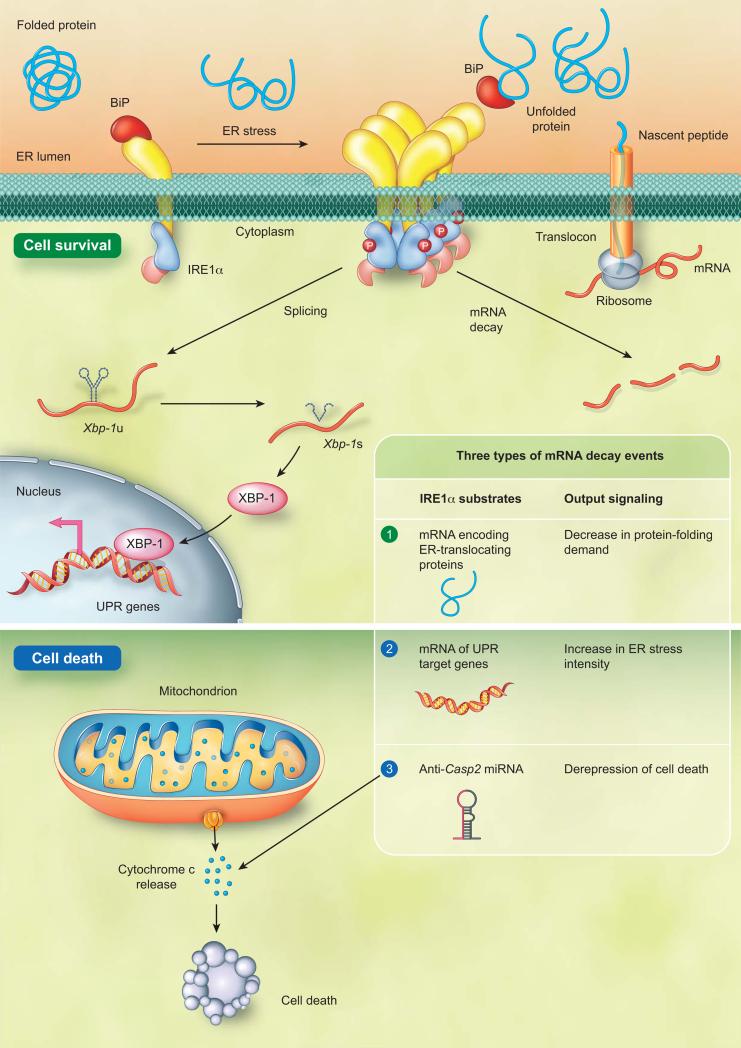

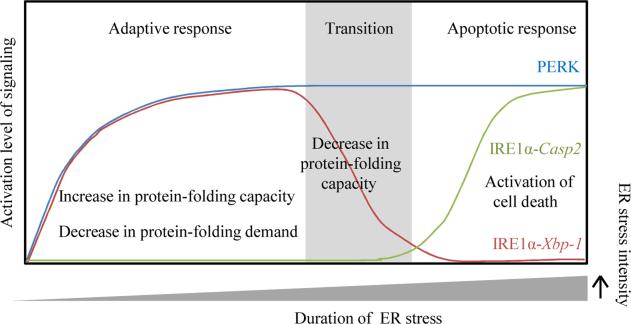

The mammalian genome encodes two isoforms of IRE1, IRE1α and IRE1β. The IRE1α is expressed ubiquitously and IRE1α knockout mice exhibit embryonic lethality. On the contrary, the IRE1β expression is restricted and IRE1β knockout mice are viable [45, 46]; therefore, most mammalian UPR research conducts on the IRE1α. IRE1α was identified as a positive regulator for cell survival. It was believed that IRE1α signaling was terminated during irremediable ER stress to enable apoptosis [1, 2, 7, 15, 47, 48]. Nevertheless, recent studies have challenged this concept by showing that IRE1α persistently adjusts protein-folding capacity, actively directs UPR signaling, and executes cell fate determination [49, 50] (Figure 2). IRE1α employs splicing and RIDD to direct cell fate throughout ER stress. Despite Xbp-1 being the only identified IRE1α splicing target, numerous types of RNA are proven to be RIDD substrates [22, 49, 50]. Even though the significance of RIDD targets is not completely understood, some RIDD events are critical for IRE1α-dependent cell fate determination. During the adaptive response, IRE1α conducts RIDD on mRNAs encoding ER-translocating proteins to prevent further increases in protein-folding demand in the ER [50]. To augment protein-folding ability, IRE1α splices the transcription factor Xbp-1 mRNA to induce the transcription of ER quality control components. If attempts to restore ER homeostasis fail, IRE1α ceases to splice Xbp-1 mRNA. Alternatively, IRE1α represses adaptive responses and activates apoptosis through RIDD [49, 50]. During the transition phase, occurring between the adaptive and apoptotic response, RIDD increases ER stress intensity through degradation of selective UPR target genes including ER protein chaperone BiP [50]. Once ER stress intensity reaches its threshold, RIDD initiates apoptosis through repression of anti-apoptotic pre-microRNAs [49]. Caspase-2 (CASP2) is a proapoptotic protease essential for apoptosis execution [51]. Upregulation of CASP2 is an indicator of apoptotic initiation. Through decay of anti-Casp2 pre-microRNAs (miRs), IRE1α activates apoptosis through upregulation of Casp2 (Figure 2) [49]. A close association of IRE1α activity and cell fate determination has been proposed for years [1, 2, 7, 15, 47, 48]. These findings provide direct evidence that IRE1α is a molecular switch and apoptosis executioner during ER stress [49]. It was previously proposed that the attenuation of IRE1 activity allows cells to initiate apoptosis [1, 2, 7, 15, 47, 48]. The identification of the IRE1α-Casp2 pathway elaborates an intriguing IRE1α signaling model: IRE1α-Xbp-1 is active in the adaptive phase and attenuated in the apoptotic phase. In parallel, activation of IRE1α-Casp2 event initiates cell death in the apoptotic phase (Figure 3).

Figure 2. IRE1α regulatory mechanisms during ER stress.

Mammalian IRE1α is repressed through a physical interaction with BiP when demand and capacity of protein folding is balanced in the ER. A dissociation of IRE1α from BiP due to an elevated level of unfolded protein in the ER leads to activation of IRE1α. The IRE1α activating processes include its auto-phosphorylation, conformational change, and higher order assembly. IRE1α directs cell fate decision through unconventional splicing and Regulated IRE1-Dependent Decay (RIDD). To prevent increasing demand of ER protein folding, IRE1α conducts RIDD to degrade the transcripts of ER-translocating proteins. In parallel, IRE1α unconventionally splices the transcript of Xbp-1 transcription factor. The spliced XBP-1 enters into the nucleus to transcriptionally reprogram UPR target genes, including ER chaperones. Under irremediable ER stress, IRE1α ceases to splice Xbp-1 mRNA. Instead, IRE1α operates RIDD on selective UPR target genes including BiP to enhance the ER stress intensity. Once the ER stress intensity reaches its threshold, IRE1α represses anti-Casp2 microRNA, miR-17, miR-34a, miR-96, and miR-125b through RIDD. IRE1α-mediated degradation of anti-Casp2 microRNAs leads to activation of apoptotic initiator Casp2 and subsequently triggers the mitochondrion-dependent apoptosis.

Figure 3. Updated model of IRE1α and PERK signaling in cell fate determination during ER stress.

The UPR signaling aimed for cell survival is considered an adaptive response during ER stress. Under irremediable ER stress, UPR represses the adaptive response and triggers an apoptotic response. IRE1α and PERK are two ER stress sensors that decrease ER protein folding demand through mRNA decay and translational inhibition, respectively. Both PERK and IRE1α signaling appear to persist throughout ER stress. IRE1α differentially triggers diverse UPR according to need. In the adaptive phase, to increase protein folding capcity, IRE1α-mediated Xbp-1 mRNA splicing is activated for transcriptional regulation of UPR target genes. In a transition phase between the adaptive and apoptotic responses, the signaling mediated by IRE1α-Xbp-1 is attenuated. In parallel, IRE1α incrases ER stress intensity through mRNA decay of selective UPR target genes including ER chaperones. During the apoptotic phase, IRE1α-Casp2 signaling is activated to initate cell death.

Is mammalian IRE1α the only major trigger of ER stress-induced apoptosis?

IRE1α is necessary and sufficient to trigger apoptosis while PERK and ATF6 are dispensable in the apoptosis activation [49]. Nonetheless, it cannot be excluded that distinct ER stress sensors may serve as major executioners of cell death in a context-specific manner. Using chemical genetic tools, the regulatory roles of the phosphor-transfer and RNase activity of IRE1α in UPR can be examined separately. The phosphor-transfer function is dispensable for Xbp-1 mRNA splicing and upregulation of CASP2 expression; however, it is required for the subsequent CASP2 cleavage and apoptosis activation, indicating that IRE1α phosphor-transfer function is essential for cell fate switch during ER stress [49, 50]. Notably, the phosphor-transfer function is mostly studied through an in vitro conditional IRE1α induction that mimics ER stress. While this experimental system is valuable to distinguish phosphor-transfer and RNase function of IRE1α, it is important to note that ATF6 and PERK are not activated through ER stress. A potentially compromised crosstalk among UPR arms raises a possibility that the IRE1α induction system might not completely resemble a genuinely biological scenario of ER stress. Hence, careful data interpretation from the conditional induction system and integration of in vivo analyses are necessary to determine whether IRE1α is the master trigger in ER stress-induced apoptosis.

The substrate specificity of mammalian IRE1α

While the four identified IRE1α-cleaved microRNAs, miR-17, miR-34a, miR-96, and miR-125b repress the common substrate Casp2, TXNIP is another target of miR-17 [52]. TXNIP is involved in β-cell death and was selected to potentially regulate ER stress-induced apoptosis based on its rapidly elevated expression under severe ER stress. Similar to the IRE1α mutation, TXNIP mutation leads to compromised apoptosis activation, indicating that TXNIP is essential for ER stress-induced apoptosis [52, 53]. While PERK-eIF2α activates TXNIP transcription, IRE1α increases TXNIP expression by degradation of miR-17. Accordingly, it is conceivable that each of four IRE1α-cleaved microRNAs might have specific substrates such as TXNIP. Based on this scenario, IRE1α might differentially degrade its individual target microRNA for fine-tuning of UPR. Another interesting feature of mammalian RIDD is that distinct substrates comprise a degree of sequence similarity within the cleavage site, whereas the flanking sequences of the cleavage sites are relatively divergent [49, 54]. This suggests that the cleavage mechanisms are likely to be conserved while the flanking sequence determines the specificity of substrate recognition. This scenario would support the hypothesis that IRE1α adjust its RNase substrate specificity to activate diverse UPR. The flexibility of IRE1α to target different substrates might rely on combinations of phosphorylation status, conformational changes, and physical associations with IRE1α regulators. As alterations of IRE1α substrate specificity lead to opposite cell fates [50], further understanding of IRE1α substrate preferences will reveal how IRE1α coordinates cellular homeostasis to determine cell fate under ER stress. Currently the target-switch of RIDD has only been reported in animals. Therefore, in order to gain a deeper understanding of UPR evolution in eukaryotes, further studies are needed to determine whether similar mechanisms exist in yeast and plants.

Plant IRE1 in ER stress response and cell fate determination

Despite the conservation of IRE1 among eukaryotes, divergent IRE1-dependent regulatory events have also been observed between plants and mammals. These evolutionarily conversed and divergent mechanisms are likely the reason for different ER stress and cell fate phenotypes observed between plants and mammals. Unlike mammalian IRE1 isoforms, the two Arabidopsis IRE1 isoforms are expressed ubiquitously with a limited tissue-specific expression pattern [55, 56]. There is no significant defect of UPR in single mutants of Arabidopsis IRE1A or IRE1B while Arabidopsis ire1 double mutants display compromised ER stress tolerance and a UPR activation phenotype [17, 18]. These observations indicate that the two Arabidopsis IRE1 homologues share partially overlapping function during the UPR. Evidence for established, dominant or specific roles of individual Arabidopsis IRE1 isoforms during UPR and cell fate regulation need to be further elucidated. Notably, it is experimentally undetermined that viable Arabidopsis ire1b are knockouts or partial loss-of-function mutants. Failure to recover a homozygous plant of putative IRE1B knockout hints that Arabidopsis IRE1B might be an essential gene similar to mammalian IRE1α [57]. Interestingly, although mammalian IRE1α is essential for UPR in goblet cells, in other cell types, there is no detectable defect in UPR target gene induction in a mammalian ire1 double mutant likely due to partially overlapping function with ATF6 and PERK [46, 58]. In contrast, although two functional homologs of ATF6, bZIP28 and bZIP17, exist in Arabidopsis [33] (Figure 1), Arabidopsis ire1 double mutants exhibit dramatic reduction of UPR target gene activation [17, 18]. These data indicate that the UPR is partially diversified between mammals and plants. On the contrary, similar IRE1 features are also observed between plants and mammals. For instance, ire1 and xbp1-1 mutants display differential phenotypes despite both being essential genes. Likewise, the mutant of Arabidopsis IRE1 splicing target, bZIP60, shows comparable ER stress tolerance with the wild type plants as opposed to Arabidopsis ire1 double mutant [17], supporting the hypothesis that the function of Arabidopsis IRE1 is not restricted to unconventional splicing like mammalian IRE1.

Interestingly, mutations of IRE1 in plants and mammals lead to opposite effects in ER stress-induced cell death phenotypes [17, 18, 32]. Ire1α−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) exhibit a greater survival rate than Ire1α+/+ MEFs under ER stress, supporting that mammalian IRE1 is an apoptosis executioner. Contrarily, Arabidopsis ire1 double mutants display compromised ER stress tolerance, instead of a greater survival rate [17, 18]. Consistently, DNA fragmentation and ion leakage are enhanced in the Arabidopsis ire1 double mutant during ER stress [32], suggesting that plant IRE1 might not function as an apoptosis executioner like its mammalian counterpart. Nevertheless, it cannot be excluded that the differences are related to dissimilar experimental settings: mammalian UPR research is mostly conducted in cell culture, while intact organisms are used in plant UPR studies. Moreover, except potential roles in protein loading reduction under ER stress [32], biological significance of the plant RIDD in cell fate determination is unknown. Further experimental validation will reveal whether the plant RIDD could process multiple substrates to control cell fate decisions similar to that seen in mammals.

Shared components of UPRosome and apoptosis

IRE1α activation is tightly controlled by its interacting protein complex termed UPRosome [15]. Most UPRosome components are involved in apoptosis, supporting that intense crosstalk exists between IRE1α activity and apoptosis activation (Table1). Specifically, although UPRosome comprises multiple components, loss-of-function mutation of the single component, such as PARP16, Bi-1, Aip-1, PTP-1B, NMHCIIB, Jab1, Nck1, and Ask1, is sufficient to alter the IRE1α splicing activity or apoptosis activation [59-66] (Table 1). Moreover, IRE1α-interactor mutants displaying either elevated or declined IRE1α splicing activity can show enhanced apoptosis, indicating that a precise activation level of IRE1α splicing is important for cell survival [59-66]. This further suggests IRE1α activation is controlled by a signaling network that maintains a delicate equilibrium of adaptive and apoptotic responses. A subtle imbalance of the equilibrium could disturb cellular homeostasis and thus alter cell fate determination [59-76]. Furthermore, the observation that a single mutation of UPRosome leads to significant defects in IRE1α signaling hints that IRE1α is differentially regulated in a context-specific manner (Table1). Because UPRosome analyses are conducted under various conditions, systematic and comparable analyses of UPRosome members will connect each hub and thus give a clearer view of IRE1α signaling network.

Table 1.

Interacting proteins of IRElα

| IRElα interactors | Function of IRElα interactors | Observed phenotype of loss-of-function mutations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| PARP16 | Poly ADP-ribose polymerase | Decreased Xbp-1 splicing / increased cell death | 59 |

| Bi-1 | Anti-apoptotic protein | Increased Xbp-1 splicing/ increased cell death | 60 |

| Aip-1 | Transducer of apoptotic signaling | Decreased Xbp-1 splicing / decreased cell death | 61 |

| Ptp-lb | Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B | Decreased Xbp-1 splicing / decreased cell death | 62 |

| NMHCIIB | Myosin cytoskeleton | Decreased Xbp-1 splicing/ compromised IRElα foci formation | 63 |

| Bax/Bak | Pro-apoptotic protein | Decreased Xbp-1 splicing/ impaired IRElα oligomerization | 67 |

| Bim/Puma | Pro-apoptotic protein | Decreased Xbp-1 splicing and UPR target genes activation | 76 |

| Jabl | Apoptosis-related protein | Decreased Xbp-1 splicing and UPR target genes activation | 64 |

| Nckl | SH2/SH3 domain containing adaptor | Decreased cell death | 65 |

| Askl | Apoptosis signal-regulated kinase | Decreased cell death/altered JNK activation | 66 |

| IRElα interactors | Function of IRElα interators | Observed phenotype of induction , overexpression, or inhibition | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traf2 | Tumor necrosis factor | Decreased JNK activation by expression of dominant-negative TRAF2 | 72 |

| Jik | JNK inhibitory kinase | Increased JNK activation by overexpression of JIK | 68 |

| Hsp90 | Heat shock protein | Decreased IRE1α protein stability by treatment of HSP90 inhibitors | 71 |

| Usp14 | Ubiquitin specific peptidase | Increase activity of ERAD by small interfering RNA silencing of Usp14 | 74 |

| SYVN1 | E3 ubiquitin ligase/anti-apoptotic factor | Increased IRE1 ubiquitination and degradation by coexpression of IRE1 and SYVN1 | 73 |

| Hsp72 | Heat shock protein | Increased Xbp-1 splicing/ decreased cell death by induction of HSP72 | 70 |

| Rack1 | Scaffold protein for activated protein kinase | Decreased IRE1 a phosphorylation by overexpression of RACK1 | 75 |

IRE1 sensing mechanisms

ER stress-sensing mechanisms are intensively studied in yeast and animals [77]. The ER stress sensors are silent through physical association with BiP, the most abundant ER-resident chaperone. Dissociation with BiP or interaction with unfolded proteins is the major trigger of IRE1 activation. Yeast IRE1 is activated through association with unfolded proteins rather than disassociation with BiP [78]; however, the physical interaction of BiP is a fine-tuning mechanism to ensure that yeast IRE1 is appropriately activated [79]. Unlike yeast IRE1, the activation mechanisms of mammalian IRE1α rely on its dissociation of BiP as opposed to a direct interaction with unfolded proteins [80]. The differences in activation mechanisms between yeast and mammalian IRE1α can be partially explained by the dissimilarity in protein structure within the sensor domain [15]. Surprisingly, a recent study revealed that mammalian IRE1β tends to interact with unfolded proteins like yeast IRE1 and it is unable to associate with BiP [81]. Accordingly, it is possible that, like yeast IRE1, binding of unfolded proteins is the primary trigger of mammalian IRE1β activation. Despite intense studies in mammals and yeast, the plant IRE1 sensing mechanisms are completely undefined. Further structural and functional analyses in plant IRE1 will be instrumental to reveal ER stress sensing mechanisms in plants.

Cell-type specific sensing mechanisms: the role of mammalian IRE1β

How the cellular homeostasis is maintained in a cell-type specific manner is a fundamental question of cell biology. It has been recently shown that IRE1β is essential for UPR specifically in goblet cells [46]. In goblet cells, IRE1β is dispensable for Xbp-1 splicing and BiP induction. Instead, IRE1β mutation leads to enhance ER stress intensity evidenced by higher level of Xbp-1 splicing and BiP induction. Moreover, IRE1β−/− mice display a distended ER phenotype potentially due to over accumulation of Mucin2 (MUC2), the most prominent protein secreted from goblet cells. This suggests that IRE1β controls MUC2 expression in goblet cells. Thus, IRE1β mutation leads to MUC2 overload in the ER and in turns trigger ER stress [46]. RIDD was proposed to be the mechanism underlying IRE1β regulation on MUC2 level in goblet cells [46]. The cell-type-specific target of IRE1β provides a molecular explanation as to how the UPR maintains a dynamic and specific secretory ability in multicellular organisms. Consistent with the notion that unfolded proteins trigger IRE1β activation, IRE1β might physically interact with specific types of unfolded protein. In the case of goblet cells, IRE1β might specifically monitor the MUC2 level in the ER and adjusts its loading into the ER through RIDD. Based on this scenario, the mammalian ER stress sensors might distinguish the type of unfolded proteins accumulated in the ER and trigger differential UPR signaling. More specifically, if the unfolded proteins are dispensable for cell survival, ER stress sensors could repress the expression of unfolded proteins through RNA decay or translational repression. Conversely, if unfolded proteins are essential for cellular function, the UPR might preferentially augment the expression of chaperones to recover the production of unfolded proteins. While the ER stress duration and intensity are considered major factors in the apoptosis threshold, the type of misfolded protein might be also critical for determination of UPR signaling outputs.

Sensing mechanisms beyond protein-folding homeostasis

Emerging evidence shows that IRE1 monitors cellular homeostasis beyond sensing unfolded protein accumulation. For instance, CRY1/CRY2-mediated circadian rhythm regulates IRE1α activity in the liver [82], suggesting that IRE1α coordinates ER function to cope with circadian-related physiological processes. These observations provide a link between the IRE1α-dependent UPR, circadian regulation, and liver metabolic processes. More importantly, because circadian rhythm has a substantial influence on UPR activation, time course studies of the UPR will require diligent experimental design and appropriate controls to avoid biases. Recently, lipid homeostasis is proven to impact the UPR activation through an unconventional sensing mechanism as the unfolded-protein-sensing domain of IRE1α and PERK is dispensable for lipid-dependent UPR activation [83]. All together, these observations support that the UPR perceives physiological and cellular signaling beyond ER protein folding homeostasis. Although it is unclear whether plant IRE1 senses signaling beyond protein-folding capacity, an Arabidopsis ire1 double mutant displaying a root-specific phenotype under unstressed conditions hints that plant IRE1 also integrates physiological signals to maintain specific secretory activity [17]; however, this hypothesis is still awaiting experimental validation.

Concluding remarks

Significant progress on defining IRE1 mechanisms has been achieved. We now know that IRE1 activities are coordinated at a systemic level to cope with dynamic secretion activity. While in vitro experimental systems and conditional IRE1 induction approaches reveal groundbreaking discoveries in the basic UPR knowledge [49, 50, 84-87], we are still far from a comprehensive understanding of UPR in intact organisms. The lethality of the mammalian IRE1α mutant represents a challenge to gaining insights into the IRE1 function in vivo. In contrast, the viability of plant IRE1 mutants enables in vivo analyses to reveal its roles in organ growth, pathogen defense, and abiotic stress responses [17, 33, 88, 89]. Moreover, with the ease of building high order plant mutants, in vivo phenotypic analyses show that Arabidopsis IRE1 and a conserved component of the G protein complex display a synergistic effect in both plant UPR activation and growth regulation. The study underscores that the UPR network can be built in intact organisms using plants as a model system [17]. With more systematic and quantitative studies of UPR in vivo, there are certainly significant findings ahead that will decipher the dynamic UPR maps close to a genuinely physiological scenario.

IRE1α degrades anti-Casp2 microRNA to initiate cell death.

The phosphor-transfer function of IRE1α is essential for cell fate determination.

IRE1 perceives developmental cues and protein folding homeostasis distinctly.

Alterations of IRE1α substrate specificity determine cell fates.

Conserved and unique features between plant and mammalian IRE1.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Danielle Loughlin for helpful comments and suggestions. We apologize to those authors whose work could not be cited owing to space constraints. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM101038-01) and NASA (NNX12AN71G).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Woehlbier U, Hetz C. Modulating stress responses by the UPRosome: a matter of life and death. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2011;36:329–337. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334:1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merksamer PI, Papa FR. The UPR and cell fate at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1003–1006. doi: 10.1242/jcs.035832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shore GC, et al. Signaling cell death from the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2011;23:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braakman I, Bulleid NJ. Kornberg RD, et al., editors. Protein Folding and Modification in the Mammalian Endoplasmic Reticulum. In Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2011. pp. 71–99. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Buchberger A, et al. Protein Quality Control in the Cytosol and the Endoplasmic Reticulum: Brothers in Arms. Molecular Cell. 2010;40:238–252. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hetz C. The unfolded protein response: controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2012;13:89–102. doi: 10.1038/nrm3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao SS, Kaufman RJ. Unfolded protein response. Current Biology. 2012;22:R622–R626. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith MH, et al. Road to Ruin: Targeting Proteins for Degradation in the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Science. 2011;334:1086–1090. doi: 10.1126/science.1209235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoseki J, et al. Mechanism and components of endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Journal of Biochemistry. 2010;147:19–25. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldman M, van der Goot FG. Novel ubiquitin-dependent quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. Trends in Cell Biology. 2009;19:357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fonseca SG, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and pancreatic beta-cell death. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;22:266–274. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Appenzeller-Herzog C, Hall MN. Bidirectional crosstalk between endoplasmic reticulum stress and mTOR signaling. Trends in Cell Biology. 2012;22:274–282. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jager R, et al. The unfolded protein response at the crossroads of cellular life and death during endoplasmic reticulum stress. Biology of the Cell. 2012;104:259–270. doi: 10.1111/boc.201100055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hetz C, Glimcher LH. Fine-Tuning of the Unfolded Protein Response: Assembling the IRE1 alpha Interactome. Molecular Cell. 2009;35:551–561. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hetz C, et al. THE UNFOLDED PROTEIN RESPONSE: INTEGRATING STRESS SIGNALS THROUGH THE STRESS SENSOR IRE1 alpha. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:1219–1243. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00001.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Y, Brandizzi F. AtIRE1A/AtIRE1B and AGB1 independently control two essential unfolded protein response pathways in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2012;69:266–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagashima Y, et al. Arabidopsis IRE1 catalyses unconventional splicing of bZIP60 mRNA to produce the active transcription factor. Sci Rep. 2011;1:29. doi: 10.1038/srep00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ali MMU, et al. Structure of the Ire1 autophosphorylation complex and implications for the unfolded protein response. Embo Journal. 2011;30:894–905. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aragon T, et al. Messenger RNA targeting to endoplasmic reticulum stress signalling sites. Nature. 2009;457:736–740. doi: 10.1038/nature07641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korennykh AV, et al. The unfolded protein response signals through high-order assembly of Ire1. Nature. 2009;457:687–693. doi: 10.1038/nature07661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hollien J, et al. Regulated Ire1-dependent decay of messenger RNAs in mammalian cells. The Journal of cell biology. 2009;186:323–331. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.So JS, et al. Silencing of Lipid Metabolism Genes through IRE1 alpha-Mediated mRNA Decay Lowers Plasma Lipids in Mice. Cell Metabolism. 2012;16:487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakaki K, et al. RNA surveillance is required for endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:8079–8084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110589109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hollien J, Weissman JS. Decay of endoplasmic reticulum-localized mRNAs during the unfolded protein response. Science. 2006;313:104–107. doi: 10.1126/science.1129631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore KA, Hollien J. The unfolded protein response in secretory cell function. Annual review of genetics. 2012;46:165–183. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vattem KM, Wek RC. Reinitiation involving upstream ORFs regulates ATF4 mRNA translation in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11269–11274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400541101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chakrabarti A, et al. A review of the mammalian unfolded protein response. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 2011;108:2777–2793. doi: 10.1002/bit.23282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raven JF, Koromilas AE. PERK and PKR: old kinases learn new tricks. Cell cycle. 2008;7:1146–1150. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.9.5811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korennykh A, Walter P. Structural basis of the unfolded protein response. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2012;28:251–277. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimmig P, et al. The unfolded protein response in fission yeast modulates stability of select mRNAs to maintain protein homeostasis. Elife. 2012;1:e00048. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mishiba K, et al. Defects in IRE1 enhance cell death and fail to degrade mRNAs encoding secretory pathway proteins in the Arabidopsis unfolded protein response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:5713–5718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219047110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwata Y, Koizumi N. Plant transducers of the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17:720–727. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun J, et al. Neuronal GPCR controls innate immunity by regulating noncanonical unfolded protein response genes. Science. 2011;332:729–732. doi: 10.1126/science.1203411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hotamisligil GS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the inflammatory basis of metabolic disease. Cell. 2010;140:900–917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fu S, et al. Aberrant lipid metabolism disrupts calcium homeostasis causing liver endoplasmic reticulum stress in obesity. Nature. 2011;473:528–531. doi: 10.1038/nature09968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hosoi T, Ozawa K. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in disease: mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Clinical Science. 2010;118:19–29. doi: 10.1042/CS20080680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li X, et al. Unfolded protein response in cancer: the physician's perspective. Journal of hematology & oncology. 2011;4:8. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang S, Kaufman RJ. The impact of the unfolded protein response on human disease. The Journal of cell biology. 2012;197:857–867. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201110131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tabas I, Ron D. Integrating the mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nature cell biology. 2011;13:184–190. doi: 10.1038/ncb0311-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodriguez D, et al. Integrating stress signals at the endoplasmic reticulum: The BCL-2 protein family rheostat. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Molecular Cell Research. 2011;1813:564–574. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marciniak SJ, et al. CHOP induces death by promoting protein synthesis and oxidation in the stressed endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3066–3077. doi: 10.1101/gad.1250704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crosti P, et al. Tunicamycin and Brefeldin A induce in plant cells a programmed cell death showing apoptotic features. Protoplasma. 2001;216:31–38. doi: 10.1007/BF02680128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watanabe N, Lam E. BAX inhibitor-1 modulates endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated programmed cell death in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:3200–3210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706659200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iwawaki T, et al. Function of IRE1 alpha in the placenta is essential for placental development and embryonic viability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16657–16662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903775106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsuru A, et al. Negative feedback by IRE1beta optimizes mucin production in goblet cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:2864–2869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212484110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin JH, et al. IRE1 signaling affects cell fate during the unfolded protein response. Science. 2007;318:944–949. doi: 10.1126/science.1146361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin JH, et al. Divergent effects of PERK and IRE1 signaling on cell viability. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Upton JP, et al. IRE1alpha cleaves select microRNAs during ER stress to derepress translation of proapoptotic Caspase-2. Science. 2012;338:818–822. doi: 10.1126/science.1226191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Han D, et al. IRE1 alpha Kinase Activation Modes Control Alternate Endoribonuclease Outputs to Determine Divergent Cell Fates. Cell. 2009;138:562–575. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vakifahmetoglu-Norberg H, Zhivotovsky B. The unpredictable caspase-2: what can it do? Trends in Cell Biology. 2010;20:150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lerner AG, et al. IRE1alpha induces thioredoxin-interacting protein to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and promote programmed cell death under irremediable ER stress. Cell Metabolism. 2012;16:250–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Menu P, et al. ER stress activates the NLRP3 inflammasome via an UPR-independent pathway. Cell death & disease. 2012;3:e261. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oikawa D, et al. Identification of a consensus element recognized and cleaved by IRE1 alpha. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38:6265–6273. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Noh SJ, et al. Characterization of two homologs of Ire1p, a kinase/endoribonuclease in yeast, in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1575:130–134. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(02)00237-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koizumi N, et al. Molecular characterization of two Arabidopsis Ire1 homologs, endoplasmic reticulum-located transmembrane protein kinases. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:949–962. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu DP, Christopher DA. Endoplasmic reticulum stress activates the expression of a sub-group of protein disulfide isomerase genes and AtbZIP60 modulates the response in Arabidopsis thaliana. Molecular genetics and genomics : MGG. 2008;280:199–210. doi: 10.1007/s00438-008-0356-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Urano F, et al. IRE1 and efferent signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 21):3697–3702. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.21.3697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jwa M, Chang P. PARP16 is a tail-anchored endoplasmic reticulum protein required for the PERK- and IRE1 alpha-mediated unfolded protein response. Nature cell biology. 2012;14:1223–+. doi: 10.1038/ncb2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lisbona F, et al. BAX Inhibitor-1 Is a Negative Regulator of the ER Stress Sensor IRE1 alpha. Molecular Cell. 2009;33:679–691. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Luo DH, et al. AIP1 is critical in transducing IRE1-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:11905–11912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710557200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gu F, et al. Protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B potentiates IRE1 signaling during endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49689–49693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400261200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.He Y, et al. Nonmuscle myosin IIB links cytoskeleton to IRE1alpha signaling during ER stress. Developmental cell. 2012;23:1141–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oono K, et al. JAB1 participates in unfolded protein responses by association and dissociation with IRE1. Neurochemistry international. 2004;45:765–772. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nguyen DT, et al. Nck-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1 and regulation of cell survival during endoplasmic reticulum stress. Molecular biology of the cell. 2004;15:4248–4260. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-11-0851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nishitoh H, et al. ASK1 is essential for endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced neuronal cell death triggered by expanded polyglutamine repeats. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1345–1355. doi: 10.1101/gad.992302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hetz C, et al. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK modulate the unfolded protein response by a direct interaction with IRE1alpha. Science. 2006;312:572–576. doi: 10.1126/science.1123480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Urano F, et al. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science. 2000;287:664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yoneda T, et al. Activation of caspase-12, an endoplastic reticulum (ER) resident caspase, through tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2-dependent mechanism in response to the ER stress. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13935–13940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gupta S, et al. HSP72 Protects Cells from ER Stress-induced Apoptosis via Enhancement of IRE1 alpha-XBP1 Signaling through a Physical Interaction. Plos Biology. 2010;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marcu MG, et al. Heat shock protein 90 modulates the unfolded protein response by stabilizing IRE1alpha. Molecular and cellular biology. 2002;22:8506–8513. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.24.8506-8513.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang Q, et al. Tumour necrosis factor receptor 1 mediates endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced activation of the MAP kinase JNK. EMBO reports. 2006;7:622–627. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gao B, et al. Synoviolin promotes IRE1 ubiquitination and degradation in synovial fibroblasts from mice with collagen-induced arthritis. EMBO reports. 2008;9:480–485. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nagai A, et al. USP14 inhibits ER-associated degradation via interaction with IRE1 alpha. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2009;379:995–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.12.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Qiu Y, et al. A crucial role for RACK1 in the regulation of glucose-stimulated IRE1alpha activation in pancreatic beta cells. Science signaling. 2010;3:ra7. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ren D, et al. BID, BIM, and PUMA are essential for activation of the BAX- and BAK-dependent cell death program. Science. 2010;330:1390–1393. doi: 10.1126/science.1190217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gardner BM, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress sensing in the unfolded protein response. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a013169. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a013169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gardner BM, Walter P. Unfolded Proteins Are Ire1-Activating Ligands That Directly Induce the Unfolded Protein Response. Science. 2011;333:1891–1894. doi: 10.1126/science.1209126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pincus D, et al. BiP binding to the ER-stress sensor Ire1 tunes the homeostatic behavior of the unfolded protein response. Plos Biology. 2010;8:e1000415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Oikawa D, et al. Activation of mammalian IRE1 alpha upon ER stress depends on dissociation of BiP rather than on direct interaction with unfolded proteins. Experimental Cell Research. 2009;315:2496–2504. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oikawa D, et al. Direct association of unfolded proteins with mammalian ER stress sensor, IRE1beta. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cretenet G, et al. Circadian clock-coordinated 12 Hr period rhythmic activation of the IRE1alpha pathway controls lipid metabolism in mouse liver. Cell Metabolism. 2010;11:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Volmer R, et al. Membrane lipid saturation activates endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response transducers through their transmembrane domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:4628–4633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217611110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cox DJ, et al. Measuring signaling by the unfolded protein response. Methods in enzymology. 2011;491:261–292. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385928-0.00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hiramatsu N, et al. Conn PM, editor. MONITORING AND MANIPULATING MAMMALIAN UNFOLDED PROTEIN RESPONSE. Methods in Enzymology, Vol 491: Unfolded Protein Response and Cellular Stress. 2011. pp. 183–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86.Teske BF, et al. Methods for analyzing eIF2 kinases and translational control in the unfolded protein response. Methods in enzymology. 2011;490:333–356. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385114-7.00019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Oslowski CM, Urano F. Conn PM, editor. MEASURING ER STRESS AND THE UNFOLDED PROTEIN RESPONSE USING MAMMALIAN TISSUE CULTURE SYSTEM. Methods in Enzymology: Unfolded Protein Response and Cellular Stress. 2011. pp. 71–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Deng Y, et al. Heat induces the splicing by IRE1 of a mRNA encoding a transcription factor involved in the unfolded protein response in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7247–7252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102117108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Moreno AA, et al. IRE1/bZIP60-mediated unfolded protein response plays distinct roles in plant immunity and abiotic stress responses. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31944. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]