Abstract

Depression is often underdiagnosed and undertreated in primary care settings, particularly in developing countries. This is, in part, due to challenges resulting from a lack of skilled mental health workers, stigma associated with mental illness, and lack of cross-culturally validated screening instruments. We conducted this study to evaluate the reliability and validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) questionnaire as a screen for diagnosing major depressive disorder among adults in Ethiopia, the second most populous country in sub-Saharan Africa. A total of 926 adults attending outpatient departments in a major referral hospital in Ethiopia participated in this study. We assessed criterion validity and performance characteristics against an independent, blinded, and psychiatrist administered semi-structured Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) interview. Overall, the PHQ-9 items showed good internal (Cronbach's alpha=0.85) and test re-test reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient=0.92). A factor analysis confirmed a 1-factor structure. Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) analysis showed that a PHQ-9 threshold score of 10 offered optimal discriminatory power with respect to diagnosis of MDD via the clinical interview (sensitivity=86% and specificity=67%). The PHQ-9 appears to be a reliable and valid instrument that may be used to diagnose major depressive disorders among Ethiopian adults.

Keywords: PHQ-9, Validation, Africa, Ethiopia, Depression

1. Introduction

Globally, mental health problems account for 13% of the total burden of disease and 31% of all years lived with disability (WHO, 2004). Mental health problems in developing countries are largely overlooked despite their high prevalence, their economic impact on families and communities, and their contribution to long-term disability (Patel et al., 2008b, Patel and Prince, 2010, Wig, 2000). According to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, major depressive disorder (MDD) is projected to become the leading cause of disability and the second leading contributor to the global burden of disease by 2020 (WHO, 2004). MDD is associated with decreased quality of life, functional decline, healthcare utilization, and increased mortality (Broadhead et al., 1990, Lowe et al., 2004, Simon et al., 1995). However, its diagnosis and treatment remains low in developing countries due, in part, to the lack of skilled mental health workers, stigma associated with mental illness, lack of cross-culturally validated screening and diagnostic instruments, and the prominence of somatic presentations of mental disorders (Patel et al., 2008a, Patel and Sartorius, 2008, Wig, 2000).

Studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa among primary health clinic patients show that 20–30% of such patients present with MDD and other psychiatric disorders as the primary or secondary reason for seeking medical care (Ngoma et al., 2003). Effective treatment of MDD requires accurate detection and diagnosis (Liu et al., 2011), which requires access to and systematic use of valid screening and diagnostic instruments.

A number of questionnaires are used to screen for MDD in both primary care and general population studies in North American and European settings (Bhugra, 2006, Bhui and Bhugra, 1997, Kroenke et al., 2001b, Mastrogianni and Bhugra, 2003). The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a brief 9-item questionnaire designed to detect MDD according to the criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-IV)(American Psychiatric and American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on, 2000), has been widely used in clinical and population-based studies across the globe as a screening and diagnostic instrument (Kroenke et al., 2001a, Spitzer et al., 2000). Additionally, the PHQ-9 has been endorsed as a valuable tool for the screening and management of MDD (Kroenke et al., 2001b). The instrument can be used to generate a diagnosis of MDD (dichotomous), as well as a continuous symptom score that may be used to monitor depression severity and patients' response to treatment (Kroenke et al., 2001b). Importantly, the PHQ-9 is a freely available, easy to understand, simple to score questionnaire that can be useful in resource limited settings of sub-Saharan African countries where administering comprehensive structured or semi-structured screening instruments can be a challenge.

To date, only three investigative teams have published studies documenting the psychometric properties of the PHQ-9 used in sub-Saharan African populations (Adewuya et al., 2006, Monahan et al., 2009, Omoro et al., 2006); and none of these studies were conducted in Ethiopia. Ethiopia, with a population of 84 million, is the second most populous country in sub-Saharan Africa. The country is undergoing social and economic changes that are predicted to have detrimental population level health effects including increased burden of chronic diseases, particularly among urban dwelling individuals. Although Ethiopia is one of the world's oldest civilizations with rich natural and mineral resources, it is also one of the poorest countries and has one of the fastest rates of urban growth in the world (Bank, 2012). Ethiopia also represents one of the leading countries of origin for African-born immigrants in the United States (Capps et al., 2011). Therefore, we conducted this study to evaluate the reliability and validity of an Amharic language version of the PHQ-9 against a psychiatrist-administered Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) (Rashid et al., 1996) reference/gold standard among urban dwelling Ethiopian adults. Specifically, we sought to evaluate the construct and criterion validity of the Amharic version of PHQ-9 for detecting an MDD diagnosis against a SCAN reference standard administered by a psychiatrist also in Amharic. We further sought to assess the optimal cut-off points for discrimination between participants with and without MDD using the PHQ-9 instrument. Additionally, we evaluated the structure of the PHQ-9 questionnaire using a contemporary item response theory, the Rasch Analysis. Finally, we conducted a sub-group analysis to examine the extent to which use of the PHQ-9 questionnaire promotes under or over detection of MDD according to participants' socio-demographic characteristics.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Participants

A total of 926 adults (≥ 18 years of age) attending outpatient departments in Saint Paul General Specialized Hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia were invited to participate in the study. Saint Paul Hospital is a referral and teaching hospital under the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health. The hospital was established to serve the economically underprivileged population, providing services free of charge to about 75% of its patients. Data collection was conducted between July and December, 2011. Prior to the start of the study, research nurses were trained for four days on the contents of the questionnaire, ethical conduct of human subjects research, and data collection techniques. All study participants provided informed consent and all research protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Addis Continental Institute of Public Health, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and the Human Subjects Division at the University of Washington, USA.

2.2 Study Procedures

We used a two-stage study design where participants were first interviewed by research nurses using the PHQ-9 questionnaire. On average it took five minutes to administer and score the PHQ-9 questionnaire. Then, on the same day, participants were interviewed using the SCAN questionnaire by licensed psychiatrists who were blind to PHQ-9 results. On average, it took 25 minutes to administer the SCAN depression interview module. During the PHQ-9 interview, we collected other general information including demographic characteristics, behavioral risk factors, and self-reported health status (WHO, 2008). Additionally we collected information concerning self-reported quality of life using the WHO Quality of Life (WHO-QOL) questionnaire.

2.2.1 Screening Test

The PHQ-9 is a 9-item depression screening and diagnostic questionnaire for MDD based on DSM-IV criteria (Kroenke et al., 2001b, Spitzer et al., 1999). The PHQ-9, originally written in English, was translated into Amharic (the official language of Ethiopia) by the lead author. To ensure proper expression and conceptualization of terminologies in local contexts, we used a standard approach of iterative back translation by panels of bilingual experts (Kessler et al., 2008, Kinder et al., 2004). The translated version was back-translated and modified until the back-translated version was comparable with the original English version. Each question requires participants to rate the frequency of a depressive symptom experienced in the two weeks prior to evaluation. These items include: 1) anhedonia, 2) depressed mood, 3) insomnia or hypersomnia, 4) fatigue or loss of energy, 5) appetite disturbances, 6) guilt or worthlessness, 7) diminished ability to think or concentrate, 8) psychomotor agitation or retardation, and 9) suicidal thoughts. Scores for each item range from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 “nearly every day” with a total score ranging from 0 to 27 (APA, 1994, Kroenke et al., 2001b, Spitzer et al., 1999). The PHQ-9 contains one additional item (item 10) which assesses functional impairment, also based on a three point scale (not difficult at all, somewhat difficult, very difficult and extremely difficult (APA, 1994, Kroenke et al., 2001b, Spitzer et al., 1999). We examined several methods of depression screening using the PHQ-9. First we examined the validity based on the total score of the nine items. Next, similar to prior studies (Fann et al., 2005), we examined the validity using a categorical algorithm.

2.2.2 Diagnostic Interview

The SCAN is a semi-structured clinical interview developed by the WHO for use by trained clinicians to diagnose psychiatric disorders among adults (Aboraya et al., 1998, Wing et al., 1990). The SCAN diagnostic interview, comprised of 28 modules, gives flexibility for diagnosing a number of mental disorders based on DSM-IV diagnostic criteria (Aboraya et al., 1998). In this study, we used the instrument's depression module. The depression module has been reported to have good psychometric properties in diverse populations and in multiple languages (Alem et al., 2004, Cheng et al., 2001, Krisanaprakornkit et al., 2006). Notably, the Amharic version of the SCAN including the depression module was shown to feasible and reliable tool in Ethiopia (percent agreement 93.0 with kappa=0.80) among Ethiopians (Alem et al., 2004).

2.2.3 Two-stage Sample Selection

As noted earlier, we used a two-stage design in which all participants who screened positive for depression on the PHQ-9 questionnaire, as well as a randomly selected sub-group of participants who screened negative for depression, were referred for clinical diagnostic interview. The SCAN diagnostic interview was conducted, within the same day, by psychiatrists who were blinded to the PHQ-9 questionnaire outcome. For the purpose of this selection, based on prior literature (Kroenke et al., 2001b), we defined positive screening for depression as having a score of ≥10 on PHQ-9. Following the PHQ-9 interview a total of 384 participants were invited to participate in the SCAN diagnostic interview (178 who screened positive and 276 who screened negative on the PHQ-9) and 363 of them agreed to do so (94% of selected positive screens and 95% of selected negative screens).

2.3 Statistical Analyses

First, we assessed data collection instruments manually for quality and completeness using range, plausibility, and cross-validation checks confirming all data were logical. We used Epi-Info software (Version 3.3.2) for data entry. We performed double data entry for a sample of completed questionnaires. After data checking and cleaning, entered data were transferred to Stata 11.0 software (Statacorp, College Station, TX) for statistical analyses.

2.3.1 Reliability

We assessed reliability using a number of agreement and consistency indices. Specifically, Cronbach's alpha was computed to assess the internal consistency of items in the PHQ-9 scale. We also computed interclass correlation coefficients to assess the test-retest reliability of PHQ-9 total scores among 5% of the study participants who completed two questionnaires on the same day.

2.3.2 Construct validity

We evaluated the construct validity, how the PHQ-9 instrument measures the underlying construct (depression), (Moller-Leimkuhler) using two approaches. First, we completed a factor analysis to assess whether a single-factor model could be generated among the nine items of PHQ-9 as reported by others (Thompson, 2004, Yu et al., 2012). Prior to performing factor analysis, we assessed the suitability of the data for performing factor analysis. This analysis showed that it is appropriate to proceed with factor analysis (Bartlett's test of sphericity (p<0.001), and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy=0.818). We then used the scree plot, presenting the eigenvalues associated with each factor, to identify the number of meaningful factors. Factors with eigenvalues >1 were assumed to be meaningful and were retained for rotation. Factors with small eigenvalues were not retained. Some investigators have noted that the PHQ-9 items may be inter-correlated with each other; hence we applied the promax oblique rotation procedure to estimate factor correlations.

Second, we used the WHO-QOL questionnaire to evaluate the construct validity of the PHQ-9 questionnaire. The WHO-QOL is a cross-cultural assessment tool that captures an individual's perception of their position in life in the context of culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns (Saxena et al., 2001). The instrument has been widely used globally including in sub-Saharan Africa (Saxena et al., 2001). We used the abbreviated version of WHO-QOL (i.e., WHOQOL-BREF) which has 26 items that cover four domains: physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment. The overall percentile score for each domain ranges from 0% (very poor) to 100% (very good). Since prior research has shown statistically significant associations between depression and quality of life (Hyphantis et al., 2011, Omoro et al., 2006), we hypothesized that lower WHO-QOL scores would be associated with higher PHQ-9 scores. We used Student's T-test to compare mean WHO-QOL scores for those classified as depressed and not depressed according to the PHQ-9 questionnaire.

2.3.3 Criterion Validity

We assessed the criterion validity by determining the concordance between the PHQ-9 score and a psychiatrist diagnosis of MDD using the SCAN. We computed the following parameters: sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood ratio, positive predictive values, and negative predictive values for the presence or absence of MDD (Zhou et al., 2011). Additionally, to identify the best PHQ-9 cut-off score to use in depression screening of Amharic-speaking adults, we completed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses to identify optimal balance of sensitivity and specificity, area under the ROC curve (AUC) and its nonparametric 95% CI (Zhou et al., 2011). Additionally, we calculated the Youden Index as an additional metric for cut off decision (Youden, 1950). The Youden index is a function of sensitivity and specificity calculated as the (sensitivity + specificity − 1). The range of the index is 0 to 100 when converted to percentages. Although there are not established values of Youden Index, values above 50% are generally considered acceptable values of diagnostic accuracy (Zhou, 2011).

Because of cost and time restrictions, we employed a two-stage design where a subset of participants screened with the PHQ-9 was assessed by a licensed psychiatrist using the SCAN depression module. Given the likelihood of referral or verification bias, we implemented two analytical strategies to assess and correct for bias introduced as a result of our study design. First, we computed the psychometric properties of the PHQ-9 by excluding all participants with unknown true depression status (i.e., those not selected for a psychiatrist administered diagnostic interview using the SCAN depression module) from analyses (Zhou et al., 2011). Then, we evaluated the Begg and Greenes adjusted estimates of psychometric properties and confidence intervals (Begg and Greenes, 1983, Carpenter and Bithell, 2000, Pepe, 2003, Zhou et al., 2011). Estimates generated from this analysis are corrected for verification bias.

2.3.4 Rating Scale Analysis

We performed a Rasch analysis to evaluate the extent to which items from the PHQ-9 are reliable and valid in detecting MDD. We used mean square infit and outfit values to determine how well individual PHQ-9 items fit the Rasch model. (Cook et al., 2011, Williams et al., 2009). The infit statistic is a weighted mean square residual value that is more sensitive to the unexpected response of an individual's ability level. The outfit statistic is the usual unweighted mean square residual and is more sensitive to unexpected observations or outliers. High infit and outfit values reflect under fit or lack of predictability of an item. As a general rule it has been suggested that mean square infit and outfit values between 0.5-1.5 are acceptable fit to the model(Linacre, 2007). Fit statistics >1.5 and <0.5 indicate too much and too little variation in response patterns and should be considered for removal from the instrument to improve fit. Therefore, we used mean square infit and outfit criteria of between 0.7-1.4 (more stringent criterion) to test model misfit (Cook et al., 2011, Williams et al., 2009). In addition to the (mis)fit of the data and the model, we also evaluated the person and item or Wright map to evaluate the hierarchy of the item difficulties. The Rasch analysis was completed using the Winsteps Software (version 3.73, Chicago, Illinois) (Linacre, 2007).

2.3.5 Validity of PHQ-9 in Subgroups

We conducted a sub-group analysis in which we used logistic regression procedures to examine the extent to which use of the PHQ-9 questionnaire promotes under or over detection of MDD vis a vis the diagnostic gold standard according to participants' demographic characteristics. We first compared the demographic characteristics of those misidentified as depressed according PHQ-9 (false positives) relative to those who were correctly classified as not depressed using the gold standard (true negative). We then compared the demographic characteristics of depressed patients misidentified as not depressed by PHQ-9 (false negatives) relative to those who were correctly classified as depressed by the gold standard (true positives).

3. Results

3.1 Participant Characteristics

A summary of selected socio-demographic and lifestyle characteristics of study participants is presented in Table 1. A total of 926 participants between the ages of 18 and 69 years (mean age=35 years, standard deviation=11 years) participated in the study. Approximately 4% of participants reported that they are current cigarette smokers and 9.6% of participants reported consuming at least 1 alcoholic beverage per week. Khat consumption (a green plant with amphetamine-like effects commonly used as a mild stimulant for social recreation and to improve work performance in Ethiopia (Belew et al., 2000, Kalix, 1987)) was reported by 5.3% of participants. Demographic characteristics, smoking behavior, alcohol consumption, and Khat consumption were similar in all participants and those who were referred for verification of psychiatric diagnoses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the entire study population (N=926), and those selected for psychiatrist diagnostic interview (N=363)

| Characteristic | All N=926 | Diagnostic Interview N=363 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | n | % | |

| Mean age (years)* | 35.1±1.7 | 34.9±11.6 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 568 | 61.3 | 229 | 63.1 |

| Men | 358 | 38.7 | 134 | 36.9 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 486 | 52.5 | 186 | 51.3 |

| Never married | 293 | 31.6 | 109 | 30.0 |

| Other | 147 | 15.9 | 68 | 18.7 |

| Education | ||||

| ≤ Primary (1-6 years) | 400 | 43.2 | 169 | 46.6 |

| Secondary (7-12 years) | 322 | 34.8 | 124 | 34.2 |

| College graduate | 204 | 22.0 | 70 | 19.3 |

| Religion | ||||

| Orthodox Christian | 692 | 74.3 | 278 | 76.6 |

| Protestant | 122 | 13.2 | 48 | 13.2 |

| Muslim | 98 | 10.6 | 31 | 8.5 |

| Other | 14 | 1.5 | 6 | 1.6 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never | 802 | 86.6 | 310 | 85.4 |

| Former | 88 | 9.5 | 41 | 11.3 |

| Current | 36 | 3.9 | 12 | 3.3 |

| Alcohol consumption past year | ||||

| Non-drinker | 528 | 57.0 | 209 | 57.6 |

| Less than once a month | 309 | 33.4 | 119 | 32.8 |

| ≥ 1 day a week | 89 | 9.6 | 35 | 9.6 |

| Khat consumption | ||||

| None | 679 | 73.7 | 261 | 71.9 |

| Former | 198 | 21.4 | 89 | 24.5 |

| Current | 49 | 5.3 | 13 | 3.6 |

Mean ± standard deviation (SD)

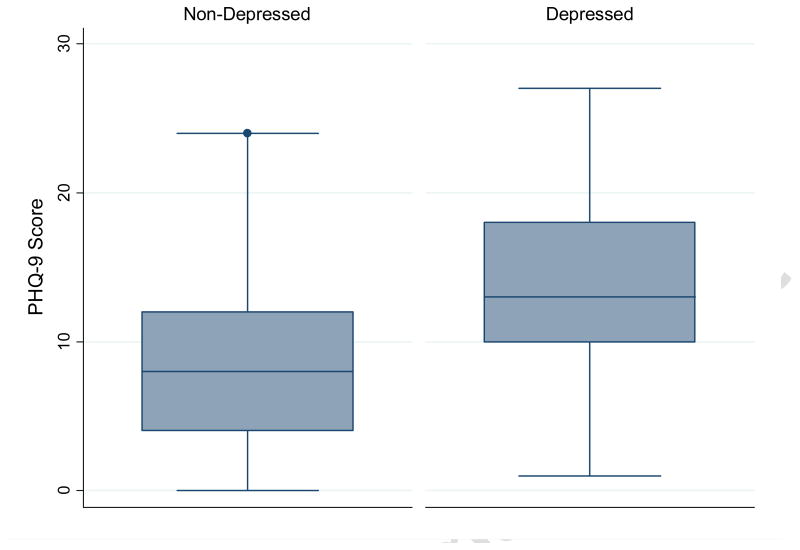

Distributions of socio-demographic and lifestyle characteristics according to participants' MDD status, based on a psychiatrist diagnosis made using the SCAN depression module, are presented in Table 2. A total of 46 patients fulfilled the DSM-IV criteria for MDD when interviewed by a psychiatrist using the SCAN depression module. Women were more likely to be diagnosed with MDD (14.4%; 95%CI 11.5-17.4%) than men (6.0%; 95%CI 5.4-6.5%). Overall, participants diagnosed with MDD, as compared with those not diagnosed, were more likely to have lower educational attainment, to be divorced or widowed, and to report poor physical and mental health status. PHQ-9 scores were higher among depressed individuals (median=13; intraquartile range (Haro et al.)=10-18) compared to the non-depressed individuals (median=8; IQR=4-12) (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the study population according psychiatrist diagnosed major depressive disorder status

| Characteristic | Depressed N= 46 | Non-depressed N=317 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | ||

| Age (years), Mean± SD | 33.7 ± 9.6 | 35.1 ± 11.9 | 0.448 |

| Sex | |||

| Women | 80.4 | 60.6 | 0.001 |

| Men | 19.6 | 39.4 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 36.9 | 53.3 | <0.001 |

| Never married | 28.3 | 30.3 | |

| Other | 34.8 | 16.4 | |

| Education | |||

| ≤ Primary (1-6) | 52.2 | 45.7 | 0.425 |

| Secondary (7-12) | 30.4 | 34.7 | |

| College graduate | 17.4 | 19.6 | |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | 78.3 | 86.4 | 0.329 |

| Former | 17.4 | 10.4 | |

| Current | 4.3 | 3.2 | |

| Alcohol consumption past year | |||

| Non-drinker | 73.9 | 55.2 | 0.060 |

| Less than once a month | 21.7 | 34.4 | |

| ≥ 1 day a week | 4.4 | 10.4 | |

| Khat chewing | |||

| None | 69.6 | 72.3 | 0.623 |

| Former | 2.2 | 3.8 | |

| Current | 28.2 | 23.9 | |

| Self-reported physical health | |||

| Excellent/very good/good | 36.9 | 47.9 | 0.002 |

| Poor/fair | 63.1 | 52.1 | |

| Self-reported mental health | |||

| Excellent/very good/good | 34.8 | 56.2 | 0.007 |

| Poor/fair | 65.2 | 43.8 |

Figure 1. Distribution of PHQ-9 scores according to major depressive disorder status.

Box plots comparing PHQ-9 scores among those classified as having major depressive disorder (right side) and those without depression (left side) based on psychiatrist diagnosed major depressive disorder using the SCAN depression module. The central box shows the data between the upper and lower quartiles, with the median represented by the middle line. The “whiskers” (lines on either side of central box) extend from the upper and lower quartiles to a distance of 1.5×IQR (interquartile range) away or the most extreme data point within that range, whichever is smaller.

3.2 Reliability and item analysis

The reliability coefficient, Cronbach's alpha for the PHQ-9 total score was 0.81 (0.82 among women and 0.79 among men) (Table 3). The correlations between nine items of the PHQ-9 and the total scores ranged from 0.57 to 0.75, and all correlations were statistically significant (all 2-tailed p-values <0.01). Depressed mood and feeling bad about oneself were the two most frequently endorsed items. Conversely, having trouble falling or staying asleep was the item least frequently endorsed by study participants. The test-retest reliability intraclass correlation coefficient of the PHQ-9 total score was 0.92 (0.91 among men and 0.93 among women).

Table 3.

PHQ-9 item level values and item-total correlations

| PHQ-9 item | Corrected item-total correlation | Alpha if item deleted |

|---|---|---|

| Little interest or pleasure in doing things | 0.62 | 0.77 |

| Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless | 0.74 | 0.75 |

| Trouble falling or staying asleep | 0.52 | 0.79 |

| Feeling tired or having little energy | 0.64 | 0.78 |

| Poor appetite or overeating | 0.54 | 0.79 |

| Feeling bad about self | 0.72 | 0.75 |

| Trouble concentrating | 0.56 | 0.78 |

| Moving or speaking slowly | 0.55 | 0.78 |

| Thoughts of being better off dead | 0.641 | 0.77 |

Overall Chronbach's Alpha = 0.81

3.3 Construct Validity

The results of the factor analysis showed that a rotated factor solution for the PHQ-9 (Table 4) contained one factor with eigenvalues >1.0, which accounted for 69.8% of the variance. Item loadings ranged from 0.39 to 0.78 (Table 4). These values suggest that depressed mood and feeling bad about self were most strongly related to the underlying construct. For both of these variables the correlation between the item and the construct was >0.70. Suicidal thoughts, lethargy and anhedonia were the next set of items strongly related to the underlying construct. For all of these variables the correlations between PHQ-9 items and the construct were all > 0.60.

Table 4.

Factor analysis of depressive symptoms using the PHQ-9 questionnaire

| Factor Loadings | |

|---|---|

| Depressive symptoms | Factor 1 |

| Little interest or pleasure in doing things | 0.55 |

| Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless | 0.78 |

| Trouble falling or staying asleep | 0.39 |

| Feeling tired or having little energy | 0.57 |

| Poor appetite or overeating | 0.45 |

| Feeling bad about self | 0.72 |

| Trouble concentrating | 0.48 |

| Moving or speaking slowly | 0.51 |

| Thoughts of being better off dead | 0.58 |

| Eigenvalue | 2.96 |

| % Variance | 69.8 |

The WHO-QOL scores for each domain are indicated in Table 5. Overall, mean WHO-QOL scores for women and men with MDD were similar for each domain. Across all domains, mean WHO-QOL scores for those classified as depressed were statistically significantly lower than those not depressed in the total sample and within sex-specific comparisons. For instance, for psychological domain participants with MDD, compared to non-depressed, were more likely to have lower mean WHO-QOL scores (42.3 (SD=15.8) versus 60.7 (SD=16.3), p<0.001).

Table 5.

Mean WHO quality of life scores according to PHQ-9 questionnaire determined MDD disorder status by domain

| Quality of life assessed by Domain | Scored high for depression on PHQ-9 | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=300) | No (n=626) | ||||

| Mean score | SD | Mean score | SD | ||

| Physical | 44.6 | 12.7 | 54.0 | 12.9 | <0.001 |

| Psychological | 42.2 | 15.8 | 60.7 | 16.3 | <0.001 |

| Social relationships | 52.5 | 23.7 | 67.4 | 21.4 | <0.001 |

| Environmental | 34.3 | 14.8 | 44.9 | 15.3 | <0.001 |

A score of ≥ 9 on PHQ-9 questionnaire was used as cutoff to indicate major depressive disorder (MDD)

3.4 Criterion Validity

The optimal cut point for maximizing the sensitivity of the PHQ-9 without loss of specificity was a score of ≥10. At this cut point, the sensitivity and specificity were 86.2% (95%CI: 77.5-92.4%) and 67.3% (95%CI: 61.3-72.9%), respectively. After adjusting for verification bias the PHQ-9 had a sensitivity of 71.1% (95%CI: 61.2-83.9%) and a specificity of 76.6% (95%CI: 74.8-79.5%) for detecting MDD. The positive predictive value was 23.0% (95%CI: 18.3-28.6%) for detecting major depression on SCAN, and the negative predictive value was 96.4% (95%CI: 94.7-97.6%) with positive likelihood ratio of 3.0 (95%CI: 2.5-3.6) and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.4 (95% CI: 0.3-0.6).

Using a screening criteria of at least 5 PHQ-9 symptoms present at least several days or more over the last two weeks, with at least one of the symptoms being a cardinal symptom (i.e., anhedonia or depressed mood), was found to have a lower sensitivity (78.3%) but better specificity (64.0%) while providing a positive predictive value of 24.0% and a negative predictive value of 95.3%. Using the 2-item screening method that uses the first two DSM-IV cardinal symptoms (i.e. anhedonia or depressed mood) present at least several days or more during the last week provided similar sensitivity (78.3%) and specificity (54.9%).

The AUC under the ROC curve for detecting MDD at a PHQ-9 score of nine or higher was 0.77 (95% CI: 0.68–0.85), and the SE was 0.043 (P<0.0001). After adjusting for verification bias, the AUC increased to 0.82 (95% CI: 0.78–0.86), and the SE was 0.023 (P<0.0001).

3.5 Rasch Scale Analysis

Table 7 indicates the item fit summary statistics for PHQ-9 using the Rasch analysis. The item difficulties ranged from 58.6 “feeling tired or low energy” (i.e., easier to endorse for participants) to 77.0 “thoughts of suicide” (i.e., difficult to endorse). None of the items misfit the model according to criteria set a priori with infit mean square values ranging from 0.81 to 1.24 and outfit mean square values ranging from 0.71 to 1.26. Finally, the separation index of PHQ-9, the ability to discriminate between participants who were depressed and those who were not, was within acceptable range.

Table 7.

Item fit statistics and misfit order for the four category of the PHQ-9 questionnaire using the Rasch Analysis

| PHQ-9 item | Measure | Fit statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infit mean square | Outfit mean square | ||

| Low energy | -0.83 | 0.98 | 1.04 |

| Anhedonia | -0.37 | 0.93 | 1.03 |

| Depressed mood | -0.34 | 0.81 | 0.74 |

| Feelings of worthlessness or guilt | -0.04 | 0.83 | 0.71 |

| Appetite disturbances | -0.02 | 1.17 | 1.23 |

| Sleep disturbances | 0.06 | 1.29 | 1.26 |

| Trouble concentrating | 0.18 | 1.23 | 1.15 |

| Psychomotor agitation/retardation | 0.65 | 1.15 | 0.96 |

| Suicidal thoughts | 0.72 | 1.04 | 0.78 |

3.6 Validity of PHQ-9 in Population Subgroups

Participants with higher educational status were less likely to be misdiagnosed using the PHQ-9 relative to SCAN diagnosis (OR=0.87; 95%CI: 0.79-0.97). No significant differences in under or over diagnosis of MDD using the PHQ-9 were noted according to other socio-demographic characteristics.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first validation of an Amharic version of the PHQ-9 questionnaire as a diagnostic tool for MDD among Ethiopians. The estimated prevalence of MDD (12.6%; 95%CI 9.2-16.1%) found in our study of clinic patients is consistent with those of previous epidemiologic studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa (Adewuya et al., 2006, Monahan et al., 2009) and among clinic patients in the US (Spitzer et al., 2000). When compared with a criterion gold standard (psychiatrist-administered SCAN diagnosis), the PHQ-9 has good reliability and validity (sensitivity (86%) and specificity (67%)) for diagnosing MDD among Ethiopian adults. The internal consistency reliability was also found to be excellent (ICC=0.92 and Cronbach's alpha=0.81). Our ROC analysis showed that a threshold of ten on the PHQ-9 was the most appropriate cutoff and offered the optimal discriminatory power in detecting MDD. In addition, our study provided strong evidence for the construct validity of the Amharic version of PHQ-9 questionnaire. Finally, the results of our factor analysis revealed unidimensionality with acceptable factor loadings on a major core depressive factor and adequate item discrimination values. Our findings are consistent with reports from community based and hospital based studies conducted globally (Adewuya et al., 2006, Fann et al., 2005, Huang et al., 2006, Kalpakjian et al., 2009, Kroenke et al., 2001b, Lotrakul et al., 2008, Monahan et al., 2009, van Steenbergen-Weijenburg et al., 2010, Yu et al., 2012).

A recent meta-analysis conducted by Manea et al (Manea et al., 2012) found the PHQ-9 to have acceptable diagnostic properties for detecting MDD for cut-off scores between 8 and 11. In their pooled analysis, the authors reported that specificity estimates summarized across 11 published studies ranged from 73% (95% CI: 63%–82%) to 96% (95% CI 94%–97%) for a cut-off scores between 7 and 15. The authors also noted substantial variability in the sensitivity for cut-off scores between 7 and 15. The sensitivity and specificity of PHQ-9 reported in our study are consistent with those reported by Manea et al (Manea et al., 2012). Notably, our study findings are comparable to what is reported in other developing countries. For instance, Lotrakul et al (Lotrakul et al., 2008) in their validation study of the Thai version of PHQ-9, found the optimal cut-off score of 9 resulted in a sensitivity of 84% and specificity of 77% when compared to a nurse administered Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) reference standard. To date, only three, investigative teams have published studies documenting the validity and reliability of the PHQ-9 when used in sub-Saharan African populations (Adewuya et al., 2006, Monahan et al., 2009, Omoro et al., 2006); and none of these included Ethiopians (supplementary table). Of the three, only one study translated the PHQ-9 instrument into local dialect (Swahili) (Omoro et al., 2006). Our test-retest reliability of 0.92 for PHQ-9 total score is excellent. This is better than the three African studies and is comparable to what is reported among US outpatient samples (Spitzer et al., 2000). Despite differences in population characteristics, sample size, and study settings, on balance, the findings of our study and those of others (Adewuya et al., 2006, Monahan et al., 2009, Omoro et al., 2006) consistently document the validity, reliability and potential benefits of using the PHQ-9 as a depression screening and diagnostic instrument among sub-Saharan Africans. By employing rigorous methodological approaches, including using a psychiatrist administered objective diagnosis for MDDs, and implementation of multiple statistical analytical methods that accounted for verification bias and other potential limitations, our study adds important new information to the sparse research literature concerning the reliability and validity of screening and diagnostic tools that may be used among sub-Saharan African populations, particularly Ethiopians.

Several investigators have noted that the PHQ-9 items may not accurately capture all components of MDD (Cook et al., 2011, Williams et al., 2009) in particular cultural contexts. Hence, in this study, we used the Rasch analysis to corroborate the evidence suggesting the PHQ-9 questionnaire is a reliable and valid measure of MDD diagnosis. The results of our Rasch analysis did not detect item misfit using the mean infit and outfit square criteria set a priori. However, of the PHQ-9 items, we found that feeling tired or having little energy was easier to endorse (understand) while the question about suicidal thoughts was the most difficult to endorse. We do not have a clear explanation for this. It is possible that there may be cultural values and factors, such as stigma, that impact endorsement of certain depressive symptoms. This question warrants future research. Another important point is one of the double-barreled items (with polar-opposite symptoms) “sleep disturbance” had the highest infit index (1.29). As noted by Williams et al (Williams et al., 2009), in their study among spinal cord injury patients, including items that contain polar opposite symptom descriptions might be confusing for some subjects and could impact the psychometric properties of the PHQ-9 (Williams et al., 2009). Investigators were able to improve the psychometric properties of the PHQ-9 by splitting items and removing those that misfit the Rasch model (Smith et al., 2009, Williams et al., 2009). Future studies need to evaluate misfitting among patients of different subgroups. Evaluating the extent to which, if at all, splitting items improves psychometric properties is also warranted.

The PHQ-9 has been reported to have a single factor in previous studies (Yu et al., 2012). Our exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses showed that a single factor model exists among the nine items of the PHQ-9 among Ethiopian adults (Thompson, 2004). This finding is consistent with prior studies that showed a single factor structure of the PHQ-9 across participants among Chinese, African Americans, and Non- Hispanic Whites (Huang et al., 2006, Yu et al., 2012). Our study results showed that depressed mood and feeling bad about self were most strongly related to the underlying construct—meeting DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for depression. For both of these items the correlation between the item and the construct was over 0.70. This means that more than 50% of the variance of these items is related to the construct underlying these items (depression). It is important to note that depressed mood is one of the cardinal symptoms of depression, while feeling bad about self is a secondary diagnostic symptom. Our observations showing strong correlation between the cardinal symptom and the underlying construct is in agreement with prior reports (Monahan et al., 2009). A study conducted among Nigerian army personnel found that factor analysis of PHQ-9 to have acceptable loadings (ranging from 0.43 to 0.63)(Okulate et al., 2004). Similar findings were reported by Monahan et al (Monahan et al., 2009). Collectively, our study results and those of others (Thompson, 2004, Yu et al., 2012) support the thesis that a single-factor structure for the PHQ-9 depressive symptoms can be generalized to many different populations. Importantly, the PHQ-9 depression questionnaire appears to be a reliable and valid screening instrument for identifying DSM-IV MDD in sub-Saharan African populations.

Major strengths of our study include the use of a clinical diagnostic gold standard to assess validity, the large sample size, and execution of a rigorous analytic plan that assessed the magnitude and impact of biases on indices used to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Amharic version of the PHQ-9 questionnaire. Using rigorous methodological approaches and a psychiatrist administered objective diagnosis; we were able to overcome some of the previously noted methodological limitations of other studies conducted among African populations. Our study expands the literature by including assessment of an Amharic version of the PHQ-9 that may be used in one of the most populous countries in Africa. Some caveats, however, must be considered when interpreting the results of our study. First, our study was conducted in an urban hospital; therefore, the result may not be generalizable to populations in rural and remote areas. In addition, our study was limited to adults. There is increasing evidence that adolescents are particularly affected by depressive disorders and thus future studies must evaluate the psychometric properties of the PHQ-9 when used in these specific populations(Richardson et al., 2010). Second, since the PHQ-9 questionnaire and the SCAN diagnostic interview were conducted during the same day, it is possible that the short time interval between the two interviews administration created carryover or recall effects and increased the reliability (Marx et al., 2003). The consistency of our study findings with those of other studies (Okulate et al., 2004, Omoro et al., 2006) and the psychometric properties of other reliability measures, in part, mitigate this concern. Third, the PHQ-9 does not make exclusions for physically induced symptoms. Consequently, we cannot rule out the possibility that our study included some participants with depressive symptoms secondary to physical illnesses and/or medical effects. The inclusion of such participants would lead to spuriously elevated prevalence estimates of MDD.

Several mental health advocates have suggested the integration of mental health with primary health care to adequately address the burden of mental disorders in low and middle income countries (Patel, 2007). One of the main challenges for such integration has been the lack of valid and easy to administer screening tools to detect the presence of mental disorders in primary care settings. Introducing brief screening and diagnostic instruments such as the PHQ-9 could be one solution to the problem. Indeed, improving the recognition of depression in clinical populations in low and middle income countries can be accomplished by the successful adaptation of depression screening instruments and diagnostic approaches from high income country settings into settings with few resources and weaker health systems (Patel et al., 2009). The benefits of having well characterized, reliable and valid screening and diagnostic instruments like the PHQ-9 in low income and resource limited clinical and research settings are potentially far reaching (Alem, 2001, Giel, 1999). Though depression screening alone is insufficient for addressing growing mental health care needs in low and middle income settings, given depression is the leading contributor to global burden of diseases having a valid screening/diagnostic instrument is an important first step towards addressing a major public health problem. There are cost effective intervention programs for depression in low income countries where valid screening instruments could be used to identify appropriate participants (Araya et al., 2003, Bolton et al., 2003, Patel et al., 2003). Importantly, early identification and proper treatment can significantly reduce the adverse impact of depression. Monitoring depressive symptoms using simple screening questionnaires like PHQ-9 that is brief, acceptable, and easy to administer is an important component of effective mental health treatment (Kroenke et al, 2010).

In conclusion, the PHQ-9 is brief, as well as easy to administer and interpret questionnaire. These are advantageous for use in resource-constrained settings like Ethiopia. Our results demonstrated that PHQ-9 is valid and reliable instrument to identify DSM-IV major depressive disorder among Ethiopian adults. Future studies should assess the responsiveness and sensitivity of PHQ-9 to treatment in Ethiopia. In addition it would also be useful to determine what constitutes a minimal clinically important change in the PHQ-9 score in Ethiopia.

Supplementary Material

Table 6a. Sensitivity and specificity for MDD diagnosis across various cut-off points of the PHQ-9 by sex.

| Sensitivity (95%CI) | Specificity (95%CI) | Youden Index | LR+(95%CI) | LR- (95%CI) | PPV (95%CI) | NPV (95%CI) | |

| All participants | |||||||

| Score≥9 | 90.4 (82.6-95.5) | 61.7 (55.6-67.5) | 52.1 | 2.6 (2.0-2.8) | 0.2 (0.1-0.3) | 45.2 (38.0-52.6) | 94.9 (90.5-97.6) |

| Score≥10 | 86.2 (77.5-92.4) | 67.3 (61.3-72.9) | 53.5 | 2.6 (2.2- . 3.2) | 0.2 (0.1-0.3) | 47.9 (40.2-55.7) | 93.3 (88.8-96.4) |

| Score≥11 | 78.7 (69.1-86.5) | 74.0 (68.3-79.1) | 52.7 | 3.4 (3.0-3.9) | 0.3 (0.2-0.5) | 54.3 (45.3-63.2) | 89.4 (84.8-93.0) |

| Women | |||||||

| Score≥9 | 90.1 (80.7-95.9) | 62.0 (54.0-69.6) | 52.1 | 2.4 (1.9-2.9) | 0.2 (0.1-0.3) | 51.0 (42.5-60.7) | 93.3 (86.7-97.3) |

| Score≥10 | 85.9 (75.6-93.0) | 68.4 (60.5-75.5) | 54.3 | 2.9 (2.5-3.5) | 0.2 (0.1-0.4) | 55.0 (45.2-64.4) | 91.5 (85.0-95.9) |

| Score≥11 | 81.7 (70.7-89.9) | 72.2 (64.5-79.0) | 53.9 | 2.9 (2.2-3.9) | 0.3 (0.1-0.4) | 56.9 (46.7-66.6) | 89.8 (83.1-94.4) |

| Men | |||||||

| Score≥9 | 91.3 (72.0-98.9) | 61.3 (51.5-70.4) | 52.6 | 2.4 (1.8-3.1) | 0.2 (0.1-0.5) | 32.8 (21.6-45.7) | 97.1 (90.1-99.7) |

| Score≥10 | 87.0 (66.4-97.2) | 65.8 (56.2-74.5) | 52.8 | 2.5 (1.9-3.4) | 0.2 (0.1-0.6) | 34.5 (22.5-48.1) | 96.1 (88.9-99.2) |

| Score≥11 | 69.6 (47.1-86.8) | 76.6 (67.6-84.1) | 46.1 | 2.9 (1.9-4.6) | 0.4 (0.2-0.7) | 38.1 (23.6-54.4) | 92.4 (84.9-96.9) |

LR+: positive likelihood ratio, LR-: negative likelihood ratio, PPV: positive predictive value, NPV: negative predictive value

Table 6b. Sensitivity and specificity for MDD diagnosis using different PHQ-9 screening criteria.

| Sensitivity (95%CI) | Specificity (95%CI) | LR+(95%CI) | LR-(95%CI) | PPV(95%CI) | NPV (95%CI) | ||

| PHQ-9 score ≥9, at least one cardinal symptom scored ≥2 | 78.3 (63.6-89.1) | 64.0 (58.5-69.3) | 2.1 (1.8-2.7) | 0.3 (0.2-0.6) | 24.0 (17.4-31.6) | 95.3 (91.5-97.7) | |

| At least 5 symptoms scored ≥ 2, at least 1 cardinal symptom | 50.0 (34.9-65.1) | 84.2 (79.7-88.1) | 3.2 (2.2-4.7) | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | 31.5 (21.1-43.4) | 92.1 (88.3-94.9) | |

| At least 5 symptoms scored ≥ 1, at least 1 cardinal symptom | 89.1 (76.4-96.4) | 42.9 (37.4-48.6) | 1.6 (1.4-1.8) | 0.2 (0.1-0.6) | 18.5 (13.6-24.2) | 96.5 (91.9-98.8) | |

| At least one cardinal symptom scored ≥ 2 | 78.3 (63.6-89.1) | 54.9 (49.2-60.5) | *1.7 (1.4-2.1) | 0.4 (0.2-0.6) | 20.1 (14.5-26.7) | 94.6 (90.2-97.4) |

LR+: positive likelihood ratio, LR-: negative likelihood ratio, PPV: positive predictive value, NPV: negative predictive value

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by an award from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (T37-MD001449). The authors wish to thank the staff of Addis Continental Institute of Public Health for their expert technical assistance. The authors would also like to thank Saint Paul Hospital for granting access to conduct the study. This research was done as partial fulfillment for the requirements of a PhD degree by one of the authors (B.G.) in the Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, School of Public Health, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aboraya A, Tien A, Stevenson J, Crosby K. Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN): introduction to WV's mental health community. W V Med J. 1998;94:326–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adewuya AO, Ola BA, Afolabi OO. Validity of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) as a screening tool for depression amongst Nigerian university students. J Affect Disord. 2006;96:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alem A. Mental health services and epidemiology of mental health problems in Ethiopia. Ethiopian medical journal. 2001;39:153–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alem A, Kebede D, Shibre T, Negash A, Deyassa N. Comparison of computer assisted scan diagnoses and clinical diagnoses of major mental disorders in Butajira, rural Ethiopia. Ethiopian medical journal. 2004;42:137–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric, A. & American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. Task Force on, D.-I. [Google Scholar]

- APA (1994) American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-IV. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: [Google Scholar]

- Araya R, Rojas G, Fritsch R, Gaete J, Rojas M, Simon G, Peters TJ. Treating depression in primary care in low-income women in Santiago, Chile: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:995–1000. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12825-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Crengle S, Gunn J, Kerse N, Fishman T, Falloon K, Hatcher S. Validation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to screen for major depression in the primary care population. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:348–53. doi: 10.1370/afm.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bank TW. The World Bank: Ethiopia Overview. 2012 Available at: www.worldbank.org/en/country/ethiopiaaccessed on September 20, 2012.

- Begg CB, Greenes RA. Assessment of diagnostic tests when disease verification is subject to selection bias. Biometrics. 1983;39:207–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belew M, Kebede D, Kassaye M, Enquoselassie F. The magnitude of khat use and its association with health, nutrition and socio-economic status. Ethiop Med J. 2000;38:11–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhugra D. Severe mental illness across cultures. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2006:17–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhui K, Bhugra D. Cross-cultural competencies in the psychiatric assessment. Br J Hosp Med. 1997;57:492–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P, Bass J, Neugebauer R, Verdeli H, Clougherty KF, Wickramaratne P, Speelman L, Ndogoni L, Weissman M. Group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in rural Uganda: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:3117–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead WE, Blazer DG, George LK, Tse CK. Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA. 1990;264:2524–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capps R, McCabe K, Fix M. New Streams: Black African Migration to the United States. Migration Policy Institute; Washington, DC.: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter J, Bithell J. Bootstrap confidence intervals: when, which, what? A practical guide for medical statisticians. Stat Med. 2000;19:1141–64. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000515)19:9<1141::aid-sim479>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng AT, Tien AY, Chang CJ, Brugha TS, Cooper JE, Lee CS, Compton W, Liu CY, Yu WY, Chen HM. Cross-cultural implementation of a Chinese version of the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) in Taiwan. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:567–72. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.6.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook KF, Bombardier CH, Bamer AM, Choi SW, Kroenke K, Fann JR. Do somatic and cognitive symptoms of traumatic brain injury confound depression screening? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:818–23. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fann JR, Bombardier CH, Dikmen S, Esselman P, Warms CA, Pelzer E, Rau H, Temkin N. Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in assessing depression following traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2005;20:501–11. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200511000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giel R. The prehistory of psychiatry in Ethiopia. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica supplementum. 1999;397:2–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haro JM, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Brugha TS, de Girolamo G, Guyer ME, Jin R, Lepine JP, Mazzi F, Reneses B, Vilagut G, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2006;15:167–80. doi: 10.1002/mpr.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang FY, Chung H, Kroenke K, Delucchi KL, Spitzer RL. Using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to measure depression among racially and ethnically diverse primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:547–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyphantis T, Kotsis K, Voulgari PV, Tsifetaki N, Creed F, Drosos AA. Diagnostic accuracy, internal consistency and convergent validity of the Greek version of PHQ-9 in diagnosing depression in rheumatological disorders. Arthritis Care Res. 2011 doi: 10.1002/acr.20505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalix P. Khat: scientific knowledge and policy issues. Br J Addict. 1987;82:47–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalpakjian CZ, Toussaint LL, Albright KJ, Bombardier CH, Krause JK, Tate DG. Patient health Questionnaire-9 in spinal cord injury: an examination of factor structure as related to gender. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32:147–56. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2009.11760766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustün TB, World Health O. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys : global perspectives on the epidemiology of mental disorders. Cambridge University Press; Published in collaboration with the World Health Organization; Cambridge; New York; Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kinder LS, Carnethon MR, Palaniappan LP, King AC, Fortmann SP. Depression and the metabolic syndrome in young adults: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:316–22. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000124755.91880.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krisanaprakornkit T, Paholpak S, Piyavhatkul N. The validity and reliability of the WHO Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN Thai Version): Mood Disorders Section. J Med Assoc Thai. 2006;89:205–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer R. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals. 2002;32:509–515. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Löwe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:345–359. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of general internal medicine. 2001a;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001b;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linacre JM. Winsteps Ministep Rasch-model computer programs 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Liu SI, Yeh ZT, Huang HC, Sun FJ, Tjung JJ, Hwang LC, Shih YH, Yeh AW. Validation of Patient Health Questionnaire for depression screening among primary care patients in Taiwan. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotrakul M, Sumrithe S, Saipanish R. Reliability and validity of the Thai version of the PHQ-9. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe B, Spitzer RL, Grafe K, Kroenke K, Quenter A, Zipfel S, Buchholz C, Witte S, Herzog W. Comparative validity of three screening questionnaires for DSM-IV depressive disorders and physicians' diagnoses. J Affect Disord. 2004;78:131–40. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manea L, Gilbody S, McMillan D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2012;184:E191–6. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx RG, Menezes A, Horovitz L, Jones EC, Warren RF. A comparison of two time intervals for test-retest reliability of health status instruments. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:730–5. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastrogianni A, Bhugra D. Globalization, cultural psychiatry and mental distress. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2003;49:163–5. doi: 10.1177/00207640030493001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller-Leimkuhler AM. Higher comorbidity of depression and cardiovascular disease in women: a biopsychosocial perspective. The world journal of biological psychiatry. 11:922–33. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2010.523481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan PO, Shacham E, Reece M, Kroenke K, Ong'or WO, Omollo O, Yebei VN, Ojwang C. Validity/reliability of PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 depression scales among adults living with HIV/AIDS in western Kenya. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:189–97. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0846-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngoma MC, Prince M, Mann A. Common mental disorders among those attending primary health clinics and traditional healers in urban Tanzania. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:349–55. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okulate GT, Olayinka MO, Jones OB. Somatic symptoms in depression: evaluation of their diagnostic weight in an African setting. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:422–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.5.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omoro SA, Fann JR, Weymuller EA, Macharia IM, Yueh B. Swahili translation and validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 depression scale in the Kenyan head and neck cancer patient population. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36:367–81. doi: 10.2190/8W7Y-0TPM-JVGV-QW6M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V. Mental health in low- and middle-income countries. Br Med Bull. 2007:81–82. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldm010. 81-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Araya R, Chowdhary N, King M, Kirkwood B, Nayak S, Simon G, Weiss HA. Detecting common mental disorders in primary care in India: a comparison of five screening questionnaires. Psychological medicine. 2008a;38:221–8. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Chisholm D, Rabe-Hesketh S, Dias-Saxena F, Andrew G, Mann A. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of drug and psychological treatments for common mental disorders in general health care in Goa, India: a randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:33–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Garrison P, de Jesus Mari J, Minas H, Prince M, Saxena S. The Lancet's series on global mental health: 1 year on. Lancet. 2008b;372:1354–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61556-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Prince M. Global mental health: a new global health field comes of age. JAMA. 2010;303:1976–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Sartorius N. From science to action: the Lancet Series on Global Mental Health. Current opinion in psychiatry. 2008;21:109–13. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f43c7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Simon G, Chowdhary N, Kaaya S, Araya R. Packages of care for depression in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS medicine. 2009;6:e1000159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe M. The statistical evaluation of medical tests for classification and prediction. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid E, Kebede D, Alem A. Evaluation of an Amharic version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) in Ethiopia. Ethiopian journal of health development. 1996;10:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson LP, McCauley E, Grossman DC, McCarty CA, Richards J, Russo JE, Rockhill C, Katon W. Evaluation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Item for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1117–23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Carlson D, Billington R, Life WGWHOQO. The WHO quality of life assessment instrument (WHOQOL-Bref): the importance of its items for cross-cultural research. Quality of life research. 2001;10:711–21. doi: 10.1023/a:1013867826835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, Barlow W. Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:352–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AB, Rush R, Wright P, Stark D, Velikova G, Sharpe M. Validation of an item bank for detecting and assessing psychological distress in cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2009;18:195–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, Hornyak R, McMurray J. Validity and utility of the PRIME-MD patient health questionnaire in assessment of 3000 obstetric-gynecologic patients: the PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire Obstetrics-Gynecology Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:759–69. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis : understanding concepts and applications. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- van Steenbergen-Weijenburg KM, de Vroege L, Ploeger RR, Brals JW, Vloedbeld MG, Veneman TF, Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Rutten FF, Beekman AT, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM. Validation of the PHQ-9 as a screening instrument for depression in diabetes patients in specialized outpatient clinics. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:235. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. The Global Burden of Disease 2004 Update. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. STEPs manual. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wig NN. WHO and mental health--a view from developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2000;78:502–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RT, Heinemann AW, Bode RK, Wilson CS, Fann JR, Tate DG. Improving measurement properties of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 with rating scale analysis. Rehabil Psychol. 2009;54:198–203. doi: 10.1037/a0015529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing JK, Babor T, Brugha T, Burke J, Cooper JE, Giel R, Jablenski A, Regier D, Sartorius N. SCAN. Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry. Archives of general psychiatry. 1990;47:589–93. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810180089012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3:32–5. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::aid-cncr2820030106>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Tam WW, Wong PT, Lam TH, Stewart SM. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for measuring depressive symptoms among the general population in Hong Kong. Comprehensive psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H. Mathematics and Statistics. Georgia State University; 2011. Statistical Inferences for the Youden Index. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou XH, McClish DK, Obuchowski NA. Statistical methods in diagnostic medicine. Wiley-Blackwell; Oxford: 2011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.