Abstract

Exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals such as bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates is prevalent among children and adolescents, but little is known regarding important sources of exposure at these sensitive life stages. In this study, we measured urinary concentrations of BPA and nine phthalate metabolites in 108 Mexican children aged 8–13 years. Associations of age, time of day, and questionnaire items on external environment, water use, and food container use with specific gravity-corrected urinary concentrations were assessed, as were questionnaire items concerning the use of 17 personal care products in the past 48-hr. As a secondary aim, third trimester urinary concentrations were measured in 99 mothers of these children, and the relationship between specific gravity-corrected urinary concentrations at these two time points was explored. After adjusting for potential confounding by other personal care product use in the past 48-hr, there were statistically significant (p <0.05) positive associations in boys for cologne/perfume use and monoethyl phthalate (MEP), mono(3-carboxypropyl) phthalate (MCPP), mono(2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl) phthalate (MEHHP), and mono(2-ethyl-5-oxohexyl) phthalate (MEOHP), and in girls for colored cosmetics use and mono-n-butyl phthalate (MBP), mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP), MEHHP, MEOHP, and mono(2-ethyl-5-carboxypentyl) phthalate (MECPP), conditioner use and MEP, deodorant use and MEP, and other hair products use and MBP. There was a statistically significant positive trend for the number of personal care products used in the past 48-hr and log-MEP in girls. However, there were no statistically significant associations between the analytes and the other questionnaire items and there were no strong correlations between the analytes measured during the third trimester and at 8–13 years of age. We demonstrated that personal care product use is associated with exposure to multiple phthalates in children. Due to rapid development, children may be susceptible to impacts from exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals; thus, reduced or delayed use of certain personal care products among children may be warranted.

Keywords: Bisphenol A, phthalates, biomarker, children, personal care products, urine

1. INTRODUCTION

Bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates are synthetic chemicals used in the production of a wide variety of consumer and medical products, and exposure to these chemicals has been documented worldwide (Hauser and Calafat, 2005; Vandenberg et al., 2007). In particular, urinary BPA and multiple phthalate metabolites have been measured in children across a variety of ages and in pregnant women where BPA and phthalates can cross the maternal-fetal placental barrier (Buckley et al., 2012; Vandenberg et al., 2007). Because exposure to these endocrine-disrupting chemicals is ubiquitous in children at various stages of development and trends for rates of endocrine-related diseases and disorders among children have increased, there is growing concern among scientists, physicians, governments, and the public that these chemicals may influence child development (Meeker, 2012).

The animal evidence suggests that BPA and phthalate exposures may influence development through the disruption of hormonally-mediated pathways (Lyche et al., 2009; vom Saal et al., 2007). These findings are supported by human epidemiology studies reporting associations between biomarkers of exposures to BPA and phthalates and endocrine-related outcomes, including shorter gestation (Cantonwine et al., 2010; Latini et al., 2003; Meeker et al., 2009; Whyatt et al., 2009), low birth weight (Chou et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2009), changes in breast and pubic hair development (Frederiksen et al., 2012; Wolff et al., 2010), and changes in brain development (Braun et al., 2009; Cho et al., 2010; Engel et al., 2010, 2009; Kim et al., 2009), body mass index (Hatch et al., 2008; Teitelbaum et al., 2012; Trasande et al., 2012; Wolff et al., 2007), and reproductive and thyroid hormone levels (Boas et al., 2010; Chevrier et al., 2012; Main et al., 2006) during various stages in childhood and adolescence. However, epidemiology studies conducted in children beyond infancy have largely been cross-sectional in design, relying on data concerning current exposures. If current exposures to BPA or phthalates in children are associated with exposures occurring in the prenatal environment, cross-sectional epidemiology studies that report associations with health outcomes may reflect effects related to exposures occurring during childhood/adolescence or in utero or both (i.e. exposures at one time point could be a surrogate for exposures at the other time point). This is a topic yet to be reported in the literature, but is important for understanding the results of such studies and in the design of future studies.

Numerous studies concerning predictors of exposure to BPA and phthalates in adult men and women, including pregnant women have been conducted (Berman et al. 2009; Braun et al. 2011; Buckley et al. 2012; Carwile et al., 2009; Casas et al., 2013; Duty et al., 2005; He et al., 2009; Hines et al., 2009; Just et al. 2010; Kwapniewski et al., 2008; Li et al., 2013; Mahalingaiah et al., 2008; Meeker et al., 2012; Parlett et al., 2012; Romero-Franco et al., 2011; Zimmerman-Downs et al., 2010). However, in comparison, exposure predictor studies in children are much more limited in number and have considered a far less variety of BPA and phthalate sources. These child exposure predictor studies have been conducted in infants (Calafat et al., 2004, 2009; Green et al., 2005), toddlers (Sathyanarayana et al., 2008), preschoolers (Casas et al., 2013), and school-aged children (Colacino et al., 2011; Li et al., 2013; Nahar et al., 2012). Additional, more comprehensive studies concerning predictors of BPA and phthalate exposure in children at all stages are needed to better inform targeted behavior modifications and policy for reducing exposures to these endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

In this study, the primary aim was to identify the determinants of urinary BPA and phthalate metabolite concentrations in 108 children from Mexico City, Mexico aged 8–13 years. A secondary aim of this study was to determine whether childhood and maternal-third trimester urinary concentrations are correlated in 99 mother-child pairs. This study considered a greater variety of BPA and phthalate sources than previous child exposure predictor studies and, to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationship between BPA and phthalate exposures at these two time points.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study Participants

This study used data from the Early Life Exposure in Mexico to ENvironmental Toxicants (ELEMENT) project that was started in 1994 and consists of three sequentially-enrolled birth cohorts from Mexico City maternity hospitals (Gonzalez-Cossio et al., 1997; Hu et al., 2006; Surkan et al., 2008). The mission of ELEMENT is to examine the influence of environmental toxicant exposures on the development and future health of the fetus and infant. Across these three cohorts, 2098 mothers were recruited during the first trimester of pregnancy or at delivery and followed at 1, 7, and 12 months post-partum and at ages 2–5 years for their offspring (n=1710) depending on the specific study. Socio-demographic, dietetic, anthropometric, and biomarker (urine, blood, bone) measures were collected at each follow-up visit. Spot urine and blood samples were collected and archived from mothers and children at different stages, including pregnancy, as well. In 2010, a subset of these children was contacted again at ages 8–13 years (n=250) through their primary caregiver based on availability of archived biomarker measures, and data from the first available 108 children were included in this current study. Urine samples and questionnaire data from these children were used in this analysis, along with urine samples from their mothers collected during third trimester when available (n=99). The questionnaire was administered by trained study nurses and filled out by the children with assistance from their primary caregiver (i.e. proxy-assisted). The research protocols were approved by the Ethics and Research Committees of all participating institutions (National Institute of Public Health, National Institute of Perinatology, and University of Michigan).

2.2 Urinary BPA and Phthalate Metabolites

Total (free + glucuronidated) BPA and nine phthalate metabolites were measured in maternal and child urine samples by isotope dilution-liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (ID-LC-MS/MS) at NSF International (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). The nine phthalate metabolites included: monoethyl phthalate (MEP), metabolite of diethyl phthalate (DEP); mono-n-butyl phthalate (MBP), metabolite of di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP); mono-isobutyl phthalate (MIBP), metabolite of di-isobutyl-phthalate (DIBP); mono(3-carboxypropyl) phthalate (MCPP), metabolite of DBP and di-n-octyl phthalate (DOP); monobenzyl phthalate (MBZP), metabolite of butylbenzyl phthalate (BBZP); and mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP), mono(2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl) phthalate (MEHHP), mono(2-ethyl-5-oxohexyl) phthalate (MEOHP), and mono(2-ethyl-5-carboxypentyl) phthalate (MECPP), metabolites of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP).

An in-house method was developed, which was a slight modification of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Laboratory Procedure Manuals for phthalate metabolites in urine (method no. 6306.03, revised: July 3, 2010) and BPA in urine (method no. 6301.01; revised: April 13, 2009) described elsewhere (Calafat et al., 2008; Silva et al., 2007). The methods were validated in accordance with Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Guidance for Industry: Bioanalytical Method Validation (2001). Samples underwent enzymatic deconjugation of glucuronidated species, online solid phase extraction, and analysis with a Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) Vantage triple quadrupole mass spectrometer using multiple reaction monitoring in negative ionization mode. Urine sample online extraction was performed using a Thermo Scientific Cyclone-P (0.5 x 50 mm) turbulent flow extraction column followed by chromatographic separation using a Waters (Milford, MA, USA) Xbridge C18 5μm (3.0 x 150 mm) analytical column. BPA and phthalate metabolite calibration ranges utilized were based on CDC methods. The validated analyte calibration curve correlation coefficient (R2) range was 0.985–1.000. The method accuracy (% nominal concentration) and precision (%RSD) were determined through six replicate analyses of analytes spiked at four different concentrations in aqueous and human urine across validation runs on three separate days (n=18) which reflects both the intra-day and inter-day variability of the assay. The accuracy (% nominal concentration) range across all analytes was 85.0 to 119% with precision (%RSD) range for both aqueous and urine quality control samples across all analytes being 1.3 to 10.8%. Specific gravity (SG) of the urine samples was also measured using a handheld digital refractometer (ATAGO Company Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

BPA and phthalate metabolite concentrations below the limit of quantitation (LOQ) were assigned a value of LOQ divided by the square root of 2. For analyses concerning SG-corrected values, the following formula was used (Mahalingaiah et al., 2008; Nahar et al., 2012): Pc = P[(SGp 1)/(SGi 1)], where Pc is the SG-adjusted BPA or phthalate metabolite concentration (ng/ml), P is the measured urinary BPA or phthalate metabolite concentration, SGp is the median of the urinary specific gravities for the sample (mothers: 1.108, children: 1.014), and SGi is the urinary specific gravity for the individual. Urinary concentrations were corrected for specific gravity to adjust for variability in urine output (Pearson et al., 2009; Mahalingaiah et al., 2008).

2.3 Questionnaire

The questionnaire, which was adapted from questionnaires used in studies in adults (Duty et al., 2005; Meeker et al., 2013), was developed to capture information on potential BPA and phthalate sources to which the children may have been exposed. The questionnaire was separated into four sections: external environment, water use, food container use, and personal care product use. The external environment section contained yes/no questions about plastic/vinyl flooring at home and at school. In the water use section, the children were asked about the primary type of water consumed (tap water, filtered water, bottled/purified water, other), as well as the primary source of drinking water at home (municipal water, private well water, bottled/delivered water). The food container use section contained a yes/no question regarding foods microwaved on or in plastic containers or wrappers, and questions on the usual frequency of consuming foods microwaved on or in plastic containers or wrappers, canned foods, and canned beverages (<1 day/month, 1–3 days/month, 1–2 days/week, 3–5 days/week, >5 days/week, multiple times/day). The personal care product use section contained yes/no questions about the use of 17 different personal care products in the past 48-hr, in addition to questions on the usual frequency of using these personal care products (not at all, <once/month, 1–3 times/month, once/week, few times/week, every day). The questionnaire asked about the use of the following personal care products: aftershave, bar soap, cologne/perfume, colored cosmetics, conditioner, deodorant, finger nail polish, hair cream, hair spray/hair gel, laundry products, liquid soap, lotion, mouthwash, other hair products (other than those listed), other toiletries (other than those listed), shampoo, and shaving cream.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SAS version 9.3 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Distributions of BPA and phthalate metabolite concentrations uncorrected for SG at third trimester and 8–13 years of age were tabulated individually for boys and girls and compared between both sexes with Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients and the associated p values were calculated for boys and girls to evaluate the relationship between these two time points for SG-corrected BPA and phthalate metabolite concentrations. Median SG-corrected BPA and phthalate metabolite concentrations for both boys and girls collectively were tabulated and compared with Wilcoxon rank-sum tests between dichotomized categories of age, time of day when the urine sample was collected, and questions relating to the external environment, water use, and food container use. A similar analysis was performed for categories of personal care products used in the past 48-hr, except that we stratified on sex because we hypothesized that there were differences in personal care product use between sexes. We did not analyze the data concerning personal care product use frequency because the results of a sensitivity analysis demonstrated excellent agreement between product use in the past 48-hr and use frequency (data not shown). For all of the two-group comparisons, we only assessed those with n ≥5 for both groups and we did not adjust the p values for multiple comparisons. We defined statistical significance as p <0.05.

To assess whether there exists a trend between the total number of personal care products used in the past 48-hr and urinary concentrations of BPA and phthalate metabolites for boys and girls individually, four indicator variables were created (6, 7, 8, ≥9 products; reference group: ≤5 products) based on the distribution of responses and were regressed against log-transformed SG-corrected concentrations. Total number of personal care products used in the past 48-hr was also modeled as an ordinal variable to obtain the p value for the trend.

Many children in this cohort reported using more than one personal care product in the past 48-hr, and multiple personal care products may contain the same chemicals and thus share associations with the same urinary biomarkers. Thus, it is plausible that the statistically significant findings from the bivariate analysis could be confounded by the use of other personal care products. To enhance our confidence in the results of the bivariate analysis, a forward stepwise regression analysis (FSRA) was performed where variables corresponding to the use of personal care products in the past 48-hr were entered and retained in final models when p <0.15. This cut point was chosen to permit the stepwise process enough flexibility so that personal care products with “suggestive” associations (0.05≤ p <0.15) would be retained in the final models. FSRA was performed for each urinary biomarker that had at least one statistically significant association that was identified in the bivariate analysis. Selected SG-corrected urinary biomarkers were log-transformed prior to performing the FSRA.

3. RESULTS

Table 1 shows the distributions of BPA and phthalate metabolite concentrations not corrected for dilution in urine samples (n=99) collected from mothers during the third trimester. Nearly all of the samples had detectable concentrations of the phthalate metabolites (0–4% <LOQ). The majority of samples also had detectable concentrations of BPA (24–31% <LOQ). Wilcoxon rank-sum tests comparing concentrations by analyte between mothers of boys and mothers of girls revealed no statistically significant differences.

Table 1.

Urinary concentrations of total (free + glucuronidated) BPA and phthalate metabolites measured in mothers of cohort at third trimester (ng/ml, uncorrected for dilution)

| Analyte | LOQ | Subjectsa | N | N (%) >LOQ | GM | Percentiles

|

Max | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | 95th | |||||||

| BPA | 0.4 | Boys | 49 | 34 (69) | 0.7 | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.6 | 1.0 | 2.6 | 4.5 | 8.9 |

| Girls | 50 | 38 (76) | 0.8 | <LOQ | 0.4 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 4.2 | 18.7 | ||

| MEP | 1.0 | Boys | 49 | 49 (100) | 130 | 26.2 | 48.9 | 136 | 393 | 905 | 1140 | 2170 |

| Girls | 50 | 50 (100) | 136 | 21.9 | 49.4 | 119 | 221 | 1004 | 1900 | 9810 | ||

| MBP | 0.5 | Boys | 49 | 49 (100) | 65.4 | 14.1 | 36.8 | 80.9 | 127 | 304 | 318 | 377 |

| Girls | 50 | 50 (100) | 64.6 | 17.0 | 31.1 | 63.8 | 157 | 200 | 606 | 1190 | ||

| MIBP | 0.2 | Boys | 49 | 47 (96) | 1.9 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 2.1 | 3.5 | 5.3 | 7.3 | 39.4 |

| Girls | 50 | 49 (98) | 2.0 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 8.3 | 12.1 | 33.9 | ||

| MCPP | 0.2 | Boys | 49 | 49 (100) | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 8.9 |

| Girls | 50 | 50 (100) | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 3.5 | 6.5 | 11.1 | ||

| MBZP | 0.2 | Boys | 49 | 48 (98) | 3.6 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 3.4 | 8.3 | 15.9 | 16.8 | 32.5 |

| Girls | 50 | 50 (100) | 3.5 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 2.9 | 6.4 | 13.0 | 29.6 | 48.4 | ||

| MEHP | 1.0 | Boys | 49 | 49 (100) | 7.0 | 2.3 | 3.5 | 7.8 | 10.8 | 16.1 | 18.8 | 24.7 |

| Girls | 50 | 48 (96) | 6.7 | 2.2 | 4.0 | 7.3 | 10.0 | 20.4 | 30.1 | 38.0 | ||

| MEHHP | 0.1 | Boys | 49 | 49 (100) | 20.9 | 4.3 | 12.5 | 25.5 | 43.6 | 76.4 | 88.5 | 111 |

| Girls | 50 | 50 (100) | 23.4 | 7.3 | 14.4 | 25.6 | 38.7 | 67.8 | 96.7 | 148 | ||

| MEOHP | 0.1 | Boys | 49 | 49 (100) | 12.1 | 2.5 | 6.6 | 15.0 | 25.2 | 46.0 | 48.4 | 64.7 |

| Girls | 50 | 50 (100) | 13.8 | 4.3 | 8.5 | 14.5 | 25.0 | 43.9 | 56.1 | 76.7 | ||

| MECPP | 0.2 | Boys | 49 | 49 (100) | 34.1 | 6.6 | 22.8 | 34.1 | 58.9 | 107 | 119 | 172 |

| Girls | 50 | 50 (100) | 38.8 | 13.3 | 24.8 | 39.3 | 65.9 | 113 | 138 | 237 | ||

GM, geometric mean; LOQ, limit of quantitation; max, maximum.

No significant differences (p >0.05) in concentrations between mothers of boys and mothers of girls based on Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Table 2 shows the distributions of BPA and phthalate metabolite concentrations not corrected for dilution in urine samples collected from boys (n=53) and girls (n=55) at 8–13 years of age. Similar to the third trimester urine samples (Table 1), a greater number of urine samples from boys and girls 8–13 years of age were above the LOQ for the phthalate metabolites (0–4% <LOQ) compared to BPA (11–13% <LOQ). Geometric mean (GM) concentrations for boys and girls 8–13 years of age were the highest for MBP rather than MEP, which was the case for the third trimester urine samples (Table 1). Except for MEP, GM urinary concentrations for boys and girls 8–13 years of age were higher compared to the third trimester urine samples from mothers of boys and girls (Table 1), respectively. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests comparing urinary concentrations by analyte between boys and girls 8–13 years of age revealed no statistically significant differences.

Table 2.

Urinary concentrations of total (free + glucuronidated) BPA and phthalate metabolites measured in cohort at 8–13 years of age (ng/ml, uncorrected for dilution)

| Analyte | LOQ | Subjectsa | N | N (%) >LOQ | GM | Percentiles

|

Max | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | 95th | |||||||

| BPA | 0.4 | Boys | 53 | 47 (89) | 1.1 | <LOQ | <LOQ | 1.2 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 4.1 | 9.4 |

| Girls | 55 | 48 (87) | 1.2 | <LOQ | 0.6 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 3.8 | 6.8 | 20.1 | ||

| MEP | 1.0 | Boys | 53 | 53 (100) | 69.5 | 16.5 | 28.0 | 62.7 | 136 | 305 | 1240 | 1580 |

| Girls | 55 | 55 (100) | 95.2 | 23.2 | 33.1 | 78.4 | 311 | 621 | 1070 | 4970 | ||

| MBP | 0.5 | Boys | 53 | 53 (100) | 92.4 | 25.2 | 56.8 | 91.2 | 130 | 317 | 420 | 732 |

| Girls | 55 | 55 (100) | 101 | 27.9 | 56.1 | 98.0 | 226 | 343 | 714 | 1760 | ||

| MIBP | 0.2 | Boys | 53 | 53 (100) | 10.7 | 3.4 | 7.1 | 11.0 | 16.7 | 26.2 | 37.8 | 100 |

| Girls | 55 | 55 (100) | 11.0 | 3.6 | 5.9 | 12.7 | 18.3 | 26.8 | 50.4 | 71.8 | ||

| MCPP | 0.2 | Boys | 53 | 53 (100) | 2.0 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 5.7 | 8.0 | 9.8 |

| Girls | 55 | 53 (96) | 2.2 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 4.1 | 6.0 | 13.7 | 140 | ||

| MBZP | 0.2 | Boys | 53 | 53 (100) | 5.6 | 1.9 | 3.2 | 5.6 | 9.3 | 13.6 | 17.6 | 28.6 |

| Girls | 55 | 55 (100) | 5.1 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 5.0 | 10.7 | 16.3 | 19.4 | 28.3 | ||

| MEHP | 1.0 | Boys | 53 | 53 (100) | 7.6 | 3.2 | 4.0 | 7.5 | 11.9 | 16.7 | 24.2 | 203 |

| Girls | 55 | 53 (98) | 6.1 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 6.4 | 10.6 | 16.1 | 18.7 | 33.7 | ||

| MEHHP | 0.1 | Boys | 53 | 53 (100) | 49.9 | 20.9 | 29.3 | 45.4 | 71.9 | 124 | 208 | 2100 |

| Girls | 55 | 55 (100) | 44.5 | 17.1 | 22.2 | 42.5 | 70.7 | 129 | 201 | 543 | ||

| MEOHP | 0.1 | Boys | 53 | 53 (100) | 22.0 | 8.5 | 11.2 | 20.9 | 34.7 | 56.4 | 88.4 | 751 |

| Girls | 55 | 55 (100) | 19.2 | 7.0 | 10.2 | 18.7 | 33.8 | 56.4 | 86.1 | 186 | ||

| MECPP | 0.2 | Boys | 53 | 53 (100) | 77.3 | 30.2 | 42.2 | 71.8 | 129 | 190 | 280 | 1620 |

| Girls | 55 | 55 (100) | 68.0 | 22.9 | 39.2 | 69.8 | 117 | 180 | 259 | 762 | ||

GM, geometric mean; LOQ, limit of quantitation; max, maximum.

No significant differences (p >0.05) in concentrations between boys and girls based on Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Table 3 shows the Spearman rank correlation coefficients comparing SG-corrected BPA and phthalate metabolite concentrations between the third trimester and 8–13 years of age. The results demonstrate that there were no strong or statistically significant correlations (absolute value range: 0.01–0.21) between these two time points.

Table 3.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (rs) of urinary concentrations of total (free + glucuronidated) BPA and phthalate metabolites measured in mothers of cohort at third trimester and in cohort at 8–13 years of age (specific gravity-corrected)

| Analyte | Subjects | N | rsa |

|---|---|---|---|

| BPA | Boys | 49 | −0.08 |

| Girls | 50 | −0.05 | |

| MEP | Boys | 49 | −0.07 |

| Girls | 50 | 0.02 | |

| MBP | Boys | 49 | 0.08 |

| Girls | 50 | −0.09 | |

| MIBP | Boys | 49 | 0.21 |

| Girls | 50 | −0.05 | |

| MCPP | Boys | 49 | 0.09 |

| Girls | 50 | 0.07 | |

| MBZP | Boys | 49 | 0.15 |

| Girls | 50 | 0.05 | |

| MEHP | Boys | 49 | 0.10 |

| Girls | 50 | 0.18 | |

| MEHHP | Boys | 49 | 0.11 |

| Girls | 50 | 0.01 | |

| MEOHP | Boys | 49 | 0.08 |

| Girls | 50 | 0.02 | |

| MECPP | Boys | 49 | 0.10 |

| Girls | 50 | −0.07 |

p >0.05.

Table 4 shows the results for SG-corrected urinary analyte concentrations of dichotomized categories of personal care product use in the past 48-hr stratified by sex. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests revealed that there were no statistically significant differences in concentrations of BPA or MBZP by self-reported use of any personal care products in the past 48-hr for boys or girls. However, boys that used cologne/perfume in the past 48-hr had significantly higher concentrations of MEP (medians: 135 vs. 49.5 ng/ml, p=0.007), MCPP (medians: 2.6 vs. 1.7 ng/ml, p=0.009), MEHHP (medians: 57.1 vs. 38.4 ng/ml, p=0.03), and MEOHP (medians: 25.7 vs. 16.5 ng/ml, p=0.01) compared with non-users. Boys that used lotion in the past 48-hr also had significantly higher concentrations of MEHP compared with non-users (medians: 9.8 vs. 6.7 ng/ml, p=0.02). For girls, users of colored cosmetics in the past 48-hr had significantly higher concentrations of MBP (medians: 246 vs. 101 ng/ml, p=0.02), MEHP (medians: 17.3 vs. 7.2 ng/ml, p=0.001), MEHHP (medians: 102 vs. 46.0 ng/ml, p=0.005), MEOHP (medians: 40.0 vs. 21.9 ng/ml, p=0.01), and MECPP (medians: 141 vs. 71.9 ng/ml, p=0.009) compared with non-users. Significantly higher concentrations of MEP were found in girls that used conditioner (276 vs. 51.8 ng/ml, p=0.001) or deodorant (medians: 147 vs. 46.4 ng/ml, p=0.003) in the past 48-hr compared with those that did not, respectively. Girls that used other hair products (other than conditioner, hair cream, hair spray/gel, or shampoo) in the past 48-hr had significantly higher concentrations of MBP (medians: 293 vs. 101 ng/ml, p=0.02), MIBP (medians: 22.0 vs. 12.0 ng/ml, p=0.008), and MCPP (medians: 4.5 vs. 2.3 ng/ml, p=0.03) compared with non-users.

Table 4.

Association of urinary concentrations of total (free + glucuronidated) BPA and phthalate metabolites in cohort at 8–13 years of age (ng/ml, specific gravity-corrected) with personal care product use in the past 48-hr (listed only for those with n ≥5 per group)

| Subjects/variable | N | Analyte

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPA | MEP | MBP | MIBP | MCPP | MBZP | MEHP | MEHHP | MEOHP | MECPP | ||

| Boys | |||||||||||

| Cologne/perfume | |||||||||||

| No | 29 | +** | +*** | +** | + | +*** | + | +* | +*** | +*** | +** |

| Yes | 24 | ||||||||||

| Deodorant | |||||||||||

| No | 22 | — | — | + | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 31 | ||||||||||

| Hair spray/gel | |||||||||||

| No | 6 | — | —* | + | — | — | — | + | + | + | + |

| Yes | 47 | ||||||||||

| Liquid soap | |||||||||||

| No | 10 | — | + | + | — | + | — | + | + | — | + |

| Yes | 43 | ||||||||||

| Lotion | |||||||||||

| No | 26 | + | + | + | + | + | + | +*** | +* | +** | +* |

| Yes | 27 | ||||||||||

| Mouthwash | |||||||||||

| No | 37 | + | + | — | — | — | + | — | — | — | + |

| Yes | 16 | ||||||||||

| Girls | |||||||||||

| Cologne/perfume | |||||||||||

| No | 18 | — | +** | + | — | — | + | + | + | — | — |

| Yes | 37 | ||||||||||

| Colored cosmetics | |||||||||||

| No | 48 | — | —** | +*** | +* | +** | + | +*** | +*** | +*** | +*** |

| Yes | 7 | ||||||||||

| Conditioner | |||||||||||

| No | 36 | +* | +*** | +* | — | + | + | — | + | + | — |

| Yes | 19 | ||||||||||

| Deodorant | |||||||||||

| No | 25 | — | +*** | + | — | — | — | + | + | — | — |

| Yes | 30 | ||||||||||

| Finger nail polish | |||||||||||

| No | 30 | + | + | — | + | — | + | + | — | + | + |

| Yes | 25 | ||||||||||

| Hair cream | |||||||||||

| No | 41 | — | + | + | + | + | — | — | + | — | — |

| Yes | 14 | ||||||||||

| Hair spray/gel | |||||||||||

| No | 22 | + | — | — | — | — | — | + | + | — | + |

| Yes | 33 | ||||||||||

| Liquid soap | |||||||||||

| No | 10 | + | +* | + | + | + | + | — | + | + | + |

| Yes | 45 | ||||||||||

| Mouthwash | |||||||||||

| No | 37 | —* | + | + | — | +* | — | — | — | —* | — |

| Yes | 18 | ||||||||||

| Other hair products | |||||||||||

| No | 50 | + | + | +*** | +*** | +*** | +* | + | +* | + | + |

| Yes | 5 | ||||||||||

+, positive association (higher median urinary concentration in the “yes” group compared to the “no” group); —, negative association (higher median urinary concentration in the “no” group compared to the “yes” group.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test:

p <0.05,

0.05≤ p <0.10,

0.10≤ p <0.15.

Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for data not stratified on sex revealed no statistically significant differences for SG-corrected BPA or phthalate metabolites in the urine of 8–10 year-olds vs. 11–13 year-olds, or in urine collected in the morning vs. the afternoon (data not shown). There were also no statistically significant differences in SG-corrected urinary analyte concentrations for dichotomized categories of plastic/vinyl flooring at home or at school, primary type of water consumed (bottled/purified water vs. other), primary source of drinking water at home (bottled/delivered vs. other), microwaving foods on or in plastic containers or wrappers, or frequency (<1–2 days/week vs. ≥1–2 days per week) of consuming microwaved foods on or in plastic containers, canned foods, or canned beverages (data not shown).

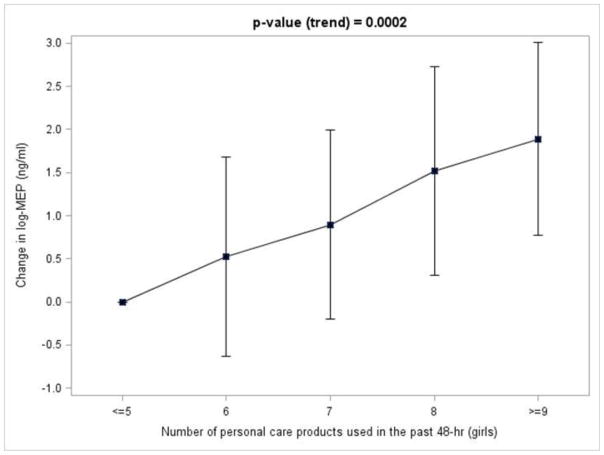

Figure 1 shows a positive trend (p=0.0002) for the number personal care products used in the past 48-hr and log-transformed SG-corrected MEP concentrations in girls. Beta coefficients for the regression model were 3.73 (≤5 personal care products, reference group), 0.52 (6 personal care products), 0.89 (7 personal care products), 1.52 (8 personal care products), and 1.89 (≥9 personal care products). Taking the antilog of the log-MEP value for each group revealed that the expected urinary MEP concentration on average for girls that used ≤5, 6, 7, 8, and ≥9 personal care products in the past 48-hr was 41.7, 70.1, 101, 191, and 276 ng/ml, respectively. There were no statistically significant trends for the number of personal care products used in the past 48-hr and concentrations of MEP for boys and any of the other analytes for boys or girls.

Figure 1.

Change in log-urinary concentration of total (free + glucuronidated) MEP in girls 8–13 years of age (ng/ml, specific gravity-corrected) associated with ≤5 personal care products used in the past 48-hr with increasing number of personal care products used in the past 48-hr

The statistically significant associations identified in the bivariate analysis also remained statistically significant in the FSRA, except for MEHP and lotion use in boys, and MIBP and MCPP and use of other hair products in girls (data not shown).

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we measured total concentrations of BPA and nine phthalate metabolites (MEP, MBP, MIBP, MCPP, MBZP, MEHP, MEHHP, MEOHP, MECPP) in spot urine samples collected from 108 Mexican children aged 8–13 years and mothers of 99 of these children during the third trimester. Urinary concentrations of BPA and the phthalate metabolites between these two time points were not correlated. After adjusting for potential confounding by other personal care product use in the past 48-hr, we found that use of cologne/perfume (MEP, MCPP, MEHHP, MEOHP) in the past 48-hr in boys and colored cosmetics (MBP, MEHP, MEHHP, MEOHP, MECPP), conditioner (MEP), deodorant (MEP), and hair products other than hair spray/gel, shampoo, conditioner, and hair cream (MBP) use in the past 48-hr in girls were statistically significant positive predictors of urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations. In girls only, there was a statistically significant positive trend between the number of personal care products used in the past 48-hr and urinary concentrations of log-MEP as well. Taken together, our results suggest that personal care product use in Mexican boys and girls are potentially important determinants of phthalate exposure.

GM urinary concentrations of the analytes at third trimester were comparable to those in urine samples from adults 20 years of age and older in US NHANES 1999–2004, except for MBP (US: 17.0–21.6 ng/ml) and MEHP (2.2–4.2 ng/ml), which were higher in this study, and MBZP (US: 8.2–9.2 ng/ml), which was lower in this study (CDC, 2013). Similar GM urinary concentrations of the phthalate metabolites at third trimester evaluated here have also been reported in pregnant Israeli women, except for MBP (Israel: 24.6 ng/ml), which was higher in our study, and MEP (Israel: 202 ng/ml) and MIBP (Israel: 13.4 ng/ml), which were lower in our study (Berman et al., 2009). GM urinary concentrations of BPA at third trimester were comparable to those in Chinese adults (He et al., 2009) 21 years of age and older and pregnant Spanish women (Casas et al., 2013) as well (data not shown).

GM urinary concentrations of the analytes at 8–13 years of age were comparable to those in urine samples from 6–11 year-old boys and girls in US NHANES 2009–2010, except for MEP (US: 35.2 ng/ml), MBP (US: 21.7 ng/ml), MEHP (US: 1.6 ng/ml), MEHHP (US: 15.0 ng/ml), MEOHP (US: 9.8 ng/ml), and MECPP (US: 27.7 ng/ml), which were higher in this study, and MBZP (US: 11.6 ng/ml), which was lower in this study. Children in our study also had similar GM urinary concentrations of MEOHP as 8–9 year-old South Korean girls, but had higher GM concentrations of MBP (South Korea: 48.9 ng/ml) and lower GM concentrations of MEHP (South Korea: 21.3 ng/ml) (Cho et al., 2010). In addition, children in our study had GM urinary concentrations of BPA that were similar to urine samples in 10–13 year-old Egyptian girls (Nahar et al., 2012) and lower than urine samples in 4 year-old Spanish boys and girls (Spain: 3.1 ng/ml) (Casas et al., 2013) (data not shown).

Our results are consistent with the findings of other studies that have examined associations between recent personal care product use and urinary concentrations of phthalate metabolites in US men (Duty et al., 2005) and US (Buckley et al., 2012; Just et al., 2010; Parlett et al., 2012), Israeli (Berman et al., 2009), and Mexican women (Romero-Franco et al., 2011). Similar positive trends with urinary MEP concentration and number of personal care products used in the past 24–48-hr have also been reported in adults (Berman et al., 2009; Duty et al., 2005; Parlett et al., 2012; Romero-Franco et al., 2011), as well as in infants (Sathyanarayana et al. 2008). Our findings are additionally supported by information on personal care product formulations (ATSDR, 1995, 1997, 2001, 2002; Anonymous, 1985; Sathyanarayana, 2008) and studies that measured the phthalate content of personal care products (Houlihan et al., 2002; Khoo and Lee, 2004; Koniecki et al., 2011). This is especially the case for MEP whose parent compound, DEP, can be found in a wide variety of personal care products, such as fragrances, deodorants, hair products, detergents, and lotions. Determinants of phthalate metabolite concentrations may have differed between the boys and girls in our study due to differences in the content, amount, and/or frequency of personal care products used.

We found no statistically significant differences in urinary concentrations of BPA or the phthalate metabolites by age or time of day, which have been reported in adults (Braun et al., 2011; Chevrier et al., 2012; Mahalingaiah et al., 2008; Meeker et al., 2012) and children (Li et al., 2013). There were also no associations with urinary BPA concentrations by bottled water, canned food, or canned beverage consumption. BPA is found in the lining of food cans and beverage storage containers (Braun and Hauser, 2011), and oral dietary exposure is believed to be the dominant exposure pathway (Vandenberg et al., 2007). Positive associations have been reported between urinary BPA concentrations and polycarbonate bottle use (Carwile et al., 2009) and canned vegetable consumption frequency (Braun et al., 2011) in US men and women, canned fish consumption frequency in Spanish women (Casas et al., 2013), canned beverage and canned fish consumption frequency in 4 year-old Spanish boys and girls (Casas et al., 2013), plastic bottle use in 3–24 year-old Chinese boys and girls (Li et al., 2013), and storage of food in plastic containers in 10–13 year-old Egyptian girls (Nahar et al., 2012). In addition, we found no statistically significant differences in the urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations by external environment, water use, or foods microwaved on or in plastic containers or wrappers. Some phthalates are used in flexible vinyl plastic, which in turn is used in the manufacture of a variety of consumer goods, such as flooring and wall coverings and food packaging (Hauser and Calafat, 2005). Ingestion of foods that are contaminated with phthalates is believed to be an important route of exposure (Swan, 2008). Others have reported that foods stored in plastic containers in 10–13 year-old Egyptian girls (Colacino et al., 2011) and bottle use in Mexican women (Romero-Franco et al., 2011) are positively associated with urinary phthalate metabolites concentrations. High correlations between air phthalate and corresponding urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations have been reported in US women, suggesting that inhalation is an important route of exposure as well (Adibi et al., 2003).

A unique strength of our study was that we analyzed urine samples that were collected from children at 8–13 years and archived urine samples from their respective mothers during third trimester. We were interested in investigating the potential relationship between these two time points because a strong association would suggest that childhood urinary measures at 8–13 years may serve as an exposure surrogate for the prenatal environment (i.e. studies that report childhood associations with health outcomes may reflect effects related to childhood or in utero exposures or both). We found that the correlations between these two time points were weak, which may reflect differences in the toxicokinetics of the children and their mothers, BPA and phthalate content of sources over time, and magnitude and frequency of BPA and phthalate exposures. On the other hand, urinary BPA and phthalate metabolite concentrations between these two time points may be correlated, but because we relied on single spot measurements, which exhibit moderate to large intra-individual variability in children (Teitelbaum et al., 2008) and adults (Adibi et al., 2008; Braun et al., 2011; Meeker et al., 2012), a correlation may not have been observed.

One limitation of our study was the small sample size, which limited the statistical power of the analyses. However, our study considered a greater variety of sources than previous studies of BPA and phthalate exposure predictors in infants (Calafat et al., 2004, 2009; Green et al., 2005), toddlers (Sathyanarayana et al., 2008), preschoolers (Casas et al., 2013), and school-aged children (Colacino et al., 2011; Li et al., 2013; Nahar et al., 2012), and was larger than all but three of these studies (Casas et al., 2013; Li et al., 2013; Sathyanarayana et al., 2008). We also did not adjust for multiple comparisons, so it is possible that some of the associations reported here may be due to chance. Nevertheless, our results are consistent with those reported in other published studies. Urinary BPA and phthalate metabolite concentrations reflect total exposure and, as a result, differentiation of exposure routes was not possible. BPA (5–6-hr) and phthalates (<24-hr) have a short biological half-lives (Braun and Hauser, 2011; Swan, 2008), and repeated measures of urinary BPA and phthalate metabolites in children (Teitelbaum et al., 2008) and adults (Adibi et al., 2008; Bruan et al., 2011; Meeker et al., 2012) have poor to moderate reproducibility. Thus, the spot urine samples collected from the children in our study may not reflect long-term exposures. In addition, the questionnaire did not ask the children to quantify the amount and frequency of personal care product use in the past 48-hr and lumped together certain personal care products into broad groups (e.g. colored cosmetics), which limited the analyses in this study. The questionnaire also did not ask about the consumption of foods not typically packaged in plastic containers or cans (e.g. fresh fruits, vegetables, and meats), which have been examined, but not found to be associated with urinary BPA in other exposure predictor studies (Braun et al., 2011; Casas et al., 2013), as well as tobacco smoke exposure, which has been reported to be positively associated with urinary BPA in adults (Braun et al., 2011; Casas et al., 2013; He et al., 2009) and children (Casas et al., 2013). However, the inclusion of increased detail and added items on the questionnaire would result in an increase in participant burden, and may introduce additional recall errors. Lastly, the results may not be generalizable to other populations, especially young children (<3 months) because they have glucuronidation pathways that are not fully mature (Lyche et al., 2009) and their personal care product use may be quite different as well.

5. CONCLUSIONS

We demonstrated that personal care product use in children is associated with exposure to multiple phthalates. Since exposure to phthalates in children is possibly associated with endocrine-related effects, reduced or delayed use of certain personal care products (e.g. cologne/perfume, colored cosmetics, etc.) in children may be warranted.

HIGHLIGHTS.

We studied urinary BPA and phthalate metabolite concentrations in Mexican children

Urinary concentrations at third trimester and 8–13 years were not correlated

Personal care product use was associated with exposure to several phthalates

Reduced or delayed use of certain personal care products in children may be warranted

Acknowledgments

Work supported by grants P20ES018171, P42ES017198, R01ES018872, and P30ES017885 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health, and by grant RD83480001 from the US Environmental Protection Agency. We thank Kurtis Kneen, Scott Clipper, Gerry Pace, David Weller, and Jennifer Bell of NSF International in Ann Arbor, MI, USA for urine analysis.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BPA

bisphenol A

- ELEMENT

Early Life Exposure in Mexico to ENvironmental Toxicants

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- BBZP

butylbenzyl phthalate

- DBP

di-n-butyl phthalate

- DEHP

di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate

- DEP

diethyl phthalate

- DIBP

di-isobutyl-phthalate

- DOP

di-n-octyl phthalate

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FSRA

forward stepwise regression analysis

- GM

geometric mean

- ID-LC-MS/MS

isotope dilution-liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- LOQ

limit of quantitation

- MBP

mono-n-butyl phthalate

- MBZP

monobenzyl phthalate

- MCPP

mono(3-carboxypropyl) phthalate

- MECPP

mono(2-ethyl-5-carboxypentyl) phthalate

- MEHP

mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate

- MEHHP

mono(2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl) phthalate

- MEOHP

mono(2-ethyl-5-ox-ohexyl) phthalate

- MEP

monoethyl phthalate

- MIBP

mono-isobutyl phthalate

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- SG

specific gravity

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Adibi JJ, Perera FP, Jedrychowski W, Camann DE, Barr D, Jacek R, Whyatt RM. Prenatal exposures to phthalates among women in New York City and Krakow, Poland. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1719–1722. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adibi JJ, Whyatt RM, Williams PL, Calafat AM, Camann D, Herrick R, Nelson H, Bhat HK, Perera FP, Silva MJ, Hauser R. Characterization of phthalate exposure among pregnant women assessed by repeat air and urine samples. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:467–473. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) Toxicological profile for diethyl phthalate. Atlanta, Georgia: 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) Toxicological profile for di-n-octylphthalate. Atlanta, Georgia: 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) Toxicological profile for di-n-butyl phthalate. Atlanta, Georgia: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) Toxicological profile for di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate. Atlanta, Georgia: 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anonymous. Final report on the safety assessment of dibutyl phthalate, dimethyl phthalate, and diethyl phthalate. J Am Coll Toxicol. 1985;4:267–303. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berman T, Hochner-Celnikier D, Calafat AM, Needham LL, Amitai Y, Wormser U, Richter E. Phthalate exposure among pregnant women in Jerusalem, Israel: results of a pilot study. Environ Int. 2009;35:353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boas M, Frederiksen H, Feldt-Rasmussen U, Skakkebæk NE, Hegedüs L, Hilsted L, Juul A, Main KM. Childhood exposure to phthalates: associations with thyroid function, insulin-like growth factor I, and growth. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:1458–1464. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braun JM, Hauser R. Bisphenol A and children’s health. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2011;23:233–239. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283445675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braun JM, Kalkbrenner AE, Calafat AM, Bernert JT, Ye X, Silva MJ, Barr DB, Sathyanarayana S, Lanphear BP. Variability and predictors of urinary bisphenol A concentrations during pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:131–137. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braun JM, Yolton K, Dietrich KN, Hornung R, Ye X, Calafat AM, Lanphear BP. Prenatal bisphenol A exposure and early childhood behavior. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:1945–1952. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buckley JP, Palmieri RT, Matuszewski JM, Herring AH, Baird DD, Hartmann KE, Hoppin JA. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2012;22:468–475. doi: 10.1038/jes.2012.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calafat AM, Needham LL, Silva MJ, Lambert G. Exposure to di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate among premature neonates in a neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e429–434. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.e429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calafat AM, Weuve J, Ye X, Jia LT, Hu H, Ringer S, Huttner K, Hauser R. Exposure to bisphenol A and other phenols in neonatal intensive care unit premature infants. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:639–644. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calafat AM, Ye X, Wong LY, Reidy JA, Needham LL. Exposure of the U.S. population to bisphenol A and 4-tertiary-octylphenol: 2003–2004. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:39–44. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cantonwine D, Meeker JD, Hu H, Sánchez BN, Lamadrid-Figueroa H, Mercado-García A, Fortenberry GZ, Calafat AM, Téllez-Rojo MM. Bisphenol A exposure in Mexico City and risk of prematurity: a pilot nested case control study. Environ Health. 2010 doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-9-62. Online 18 October 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carwile JL, Luu HT, Bassett LS, Driscoll DA, Yuan C, Chang JY, Ye X, Calafat AM, Michels KB. Polycarbonate bottle use and urinary bisphenol A concentrations. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:1368–1372. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casas M, Valvi D, Luque N, Ballesteros-Gomez A, Carsin AE, Fernandez MF, Koch HM, Mendez MA, Sunyer J, Rubio S, Vrijheid M. Dietary and sociodemographic determinants of bisphenol A urine concentrations in pregnant women and children. Environ Int. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2013.02.014. Epub 2013 Mar 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Updated tables. Atlanta, GA: Mar, 2013. Fourth national report on human exposure to environmental chemicals. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chevrier J, Gunier RB, Bradman A, Holland NT, Calafat AM, Eskenazi B, Harley KG. Maternal urinary bisphenol A during pregnancy and maternal and neonatal thyroid function in The CHAMACOS Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121:138–144. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho SC, Bhang SY, Hong YC, Shin MS, Kim BN, Kim JW, Yoo HJ, Cho IH, Kim HW. Relationship between environmental phthalate exposure and the intelligence of school-age children. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:1027–1032. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chou WC, Chen JL, Lin CF, Chen YC, Shih FC, Chuang CY. Biomonitoring of bisphenol A concentrations in maternal and umbilical cord blood in regard to birth outcomes and adipokine expression: a birth cohort study in Taiwan. Environ Health. 2011 doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-10-94. Online 3 November 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colacino JA, Soliman AS, Calafat AM, Nahar MS, Van Zomeren-Dohm A, Hablas A, Seifeldin IA, Rozek LS, Dolinoy DC. Exposure to phthalates among premenstrual girls from rural and urban Gharbiah, Egypt: a pilot exposure assessment study. Environ Health. 2011 doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-10-40. Online 16 May 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duty SM, Ackerman RM, Calafat AM, Hauser R. Personal care product use predicts urinary concentrations of some phthalate monoesters. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:1530–1535. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engel SM, Miodovnik A, Canfield RL, Zhu C, Silva MJ, Calafat AM, Wolff MS. Prenatal phthalate exposure is associated with childhood behavior and executive functioning. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:565–571. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engel SM, Zhu C, Berkowitz GS, Calafat AM, Silva MJ, Miodovnik A, Wolff MS. Prenatal phthalate exposure and performance on the Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale in a multiethnic birth cohort. Neurotoxicology. 2009;30:522–528. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Guidance for industry: bioanalytical method validation, May 2001. Rockville, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frederiksen H, Sørensen K, Mouritsen A, Aksglaede L, Hagen CP, Petersen JH, Skakkebaek NE, Andersson AM, Juul A. High urinary phthalate concentration associated with delayed pubarche in girls. Int J Androl. 2012;35:216–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2012.01260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonzalez-Cossio T, Peterson KE, Sanín LH, Fishbein E, Palazuelos E, Aro A, Hernandez-Avila M, Hu H. Pediatrics. 1997;100:856–862. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.5.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green R, Hauser R, Calafat AM, Weuve J, Schettler T, Ringer S, Huttner K, Hu H. Use of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate-containing medical products and urinary levels of mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate in neonatal intensive care unit infants. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:1222–1225. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hatch EE, Nelson JW, Qureshi MM, Weinberg J, Moore LL, Singer M, Webster TF. Association of urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations with body mass index and waist circumference: a cross-sectional study of NHANES data, 1999–2002. Environ Health. 2008 doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-7-27. Online 3 June 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hauser R, Calafat AM. Phthalates and human health. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62:806–818. doi: 10.1136/oem.2004.017590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He Y, Miao M, Herrinton LJ, Wu C, Yuan W, Zhou Z, Li DK. Bisphenol A levels in blood and urine in a Chinese population and the personal factors affecting the levels. Environ Res. 2009;109:629–633. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hines CJ, Nilsen Hopf NB, Deddens JA, Calafat AM, Silva MJ, Grote AA, Sammons DL. Urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations among workers in selected industries: a pilot biomonitoring study. Ann Occup Hyg. 2009;53:1–17. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/men066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Houlihan J, Brody C, Bryony S. Not too pretty: phthalates, beauty products & the FDA. Environmental Working Group; Washington, DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu H, Téllez-Rojo MM, Bellinger D, Smith D, Ettinger AS, Lamadrid-Figueroa H, Schwartz J, Schnaas L, Mercado-García A, Hernández-Avila M. Fetal lead exposure at each stage of pregnancy as a predictor of infant mental development. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:1730–1735. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Just AC, Adibi JJ, Rundle AG, Calafat AM, Camann DE, Hauser R, Silva MJ, Whyatt RM. Urinary and air phthalate concentrations and self-reported use of personal care products among minority pregnant women in New York City. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2010;20:625–633. doi: 10.1038/jes.2010.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim BN, Cho SC, Kim Y, Shin MS, Yoo HJ, Kim JW, Yang YH, Kim HW, Bhang SY, Hong YC. Phthalates exposure and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in school-age children. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;15:958–963. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koniecki D, Wang R, Moody RP, Zhu J. Phthalates in cosmetic and personal care products: concentrations and possible dermal exposure. Environ Res. 2011;111:329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koo HJ, Lee BM. Estimated exposure to phthalates in cosmetics and risk assessment. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2004;67:1901–1914. doi: 10.1080/15287390490513300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kwapniewski R, Kozaczka S, Hauser R, Silva MJ, Calafat AM, Duty SM. Occupational exposure to dibutyl phthalate among manicurists. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50:705–711. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181651571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Latini G, De Felice C, Presta G, Del Vecchio A, Paris I, Ruggieri F, Mazzeo P. In utero exposure to di-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate and duration of human pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1783–1785. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li X, Ying GG, Zhao JL, Chen ZF, Lai HJ, Su HC. 4-Nonylphenol, bisphenol-A and triclosan levels in human urine of children and students in China, and the effects of drinking these bottled materials on the levels. Environ Int. 2013;52:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2011.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lyche JL, Gutleb AC, Bergman A, Eriksen GS, Murk AJ, Ropstad E, Saunders M, Skaare JU. Reproductive and developmental toxicity of phthalates. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2009;12:225–249. doi: 10.1080/10937400903094091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mahalingaiah S, Meeker JD, Pearson KR, Calafat AM, Ye X, Petrozza J, Hauser R. Temporal variability and predictors of urinary bisphenol A concentrations in men and women. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:173–178. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Main KM, Mortensen GK, Kaleva MM, Boisen KA, Damgaard IN, Chellakooty M, Schmidt IM, Suomi AM, Virtanen HE, Petersen DV, Andersson AM, Toppari J, Skakkebaek NE. Human breast milk contamination with phthalates and alterations of endogenous reproductive hormones in infants three months of age. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:270–276. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meeker JD. Exposure to environmental endocrine disruptors and child development. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:952–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meeker JD, Calafat AM, Hauser R. Urinary phthalate metabolites and their biotransformation products: predictors and temporal variability among men and women. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2012;22:376–385. doi: 10.1038/jes.2012.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meeker JD, Cantonwine DE, Rivera-González LO, Ferguson KK, Mukherjee B, Calafat AM, Ye X, Anzalota Del Toro LV, Crespo-Hernández N, Jiménez-Vélez B, Alshawabkeh AN, Cordero JF. Distribution, variability, and predictors of urinary concentrations of phenols and parabens among pregnant women in Puerto Rico. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47:3439–3437. doi: 10.1021/es400510g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meeker JD, Hu H, Cantonwine DE, Lamadrid-Figueroa H, Calafat AM, Ettinger AS, Hernandez-Avila M, Loch-Caruso R, Téllez-Rojo MM. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009;117:1587–1592. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nahar MS, Soliman AS, Colacino JA, Calafat AM, Battige K, Hablas A, Seifeldin IA, Dolinoy DC, Rozek LS. Urinary bisphenol A concentrations in girls from rural and urban Egypt: a pilot study. Envion Health. 2012 doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-11-20. Online 2 April 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parlett LE, Calafat AM, Swan SH. Women’s exposure to phthalates in relation to use of personal care products. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/jes.2012.105. Online 21 November 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pearson MA, Lu C, Schmotzer BJ, Waller LA, Riederer AM. Evaluation of physiological measures for correcting variation in urinary output: Implications for assessing environmental chemical exposure in children. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 19:336–342. doi: 10.1038/jes.2008.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Romero-Franco M, Hernández-Ramírez RU, Calafat AM, Cebrián ME, Needham LL, Teitelbaum S, Wolff MS, López-Carrillo L. Personal care product use and urinary levels of phthalate metabolites in Mexican women. Environ Int. 2011;37:867–871. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sathyanarayana S, Karr CJ, Lozano P, Brown E, Calafat AM, Liu F, Swan SH. Baby care products: possible sources of infant phthalate exposure. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e260–268. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Silva MJ, Samandar E, Preau JL, Jr, Reidy JA, Needham LL, Calafat AM. Quantification of 22 phthalate metabolites in human urine. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2007;860:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Surkan PJ, Schnaas L, Wright RJ, Téllez-Rojo MM, Lamadrid-Figueroa H, Hu H, Hernández-Avila M, Bellinger DC, Schwartz J, Perroni E, Wright RO. Maternal self-esteem, exposure to lead, and child neurodevelopment. Neurotoxicology. 2008;29:278–285. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Swan SH. Environmental phthalate exposure in relation to reproductive outcomes and other health endpoints in humans. Environ Res. 2008;108:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Teitelbaum SL, Britton JA, Calafat AM, Ye X, Silva MJ, Reidy JA, Galvez MP, Brenner BL, Wolff MS. Temporal variability in urinary concentrations of phthalate metabolites, phytoestrogens and phenols among minority children in the United States. Environ Res. 2008;106:257–269. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Teitelbaum SL, Mervish N, Moshier EL, Vangeepuram N, Galvez MP, Calafat AM, Silva MJ, Brenner BL, Wolff MS. Associations between phthalate metabolite urinary concentrations and body size measures in New York City children. Environ Res. 2012;112:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Trasande L, Attina TM, Blustein J. Association between urinary bisphenol A concentration and obesity prevalence in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2012;308:1113–1121. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vandenberg LN, Hauser R, Marcus M, Olea N, Welshons WV. Human exposure to bisphenol A (BPA) Reprod Toxicol. 2007;24:139–177. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.vom Saal FS, Akingbemi BT, Belcher SM, Birnbaum LS, Crain DA, Eriksen M, Farabollini F, Guillette LJ, Jr, Hauser R, Heindel JJ, Ho SM, Hunt PA, Iguchi T, Jobling S, Kanno J, Keri RA, Knudsen KE, Laufer H, LeBlanc GA, Marcus M, McLachlan JA, Myers JP, Nadal A, Newbold RR, Olea N, Prins GS, Richter CA, Rubin BS, Sonnenschein C, Soto AM, Talsness CE, Vandenbergh JG, Vandenberg LN, Walser-Kuntz DR, Watson CS, Welshons WV, Wetherill Y, Zoeller RT. Chapel Hill bisphenol A expert panel consensus statement: integration of mechanisms, effects in animals and potential to impact human health at current levels of exposure. Reprod Toxicol. 2007;24:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Whyatt RM, Adibi JJ, Calafat AM, Camann DE, Rauh V, Bhat HK, Perera FP, Andrews H, Just AC, Hoepner L, Tang D, Hauser R. Prenatal di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate exposure and length of gestation among an inner-city cohort. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e1213–1220. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wolff MS, Teitelbaum SL, Pinney SM, Windham G, Liao L, Biro F, Kushi LH, Erdmann C, Hiatt RA, Rybak ME, Calafat AM Breast Cancer and Environment Research Centers. Investigation of relationships between urinary biomarkers of phytoestrogens, phthalates, and phenols and pubertal stages in girls. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:1039–1046. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wolff MS, Teitelbaum SL, Windham G, Pinney SM, Britton JA, Chelimo C, Godbold J, Biro F, Kushi LH, Pfeiffer CM, Calafat AM. Pilot study of urinary biomarkers of phytoestrogens, phthalates, and phenols in girls. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:116–121. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Y, Lin L, Cao Y, Chen B, Zheng L, Ge RS. Phthalate levels and low birth weight: a nested case-control study of Chinese newborns. J Pediatr. 2009;155:500–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zimmerman-Downs JM, Shuman D, Stull SC, Ratzlaff RE. Bisphenol A blood and saliva levels prior to and after dental sealant placement in adults. J Dent Hyg. 2010;84:145–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]